The Association between ADHD Symptoms and Antisocial Behavior: Differential Effects of Maternal and Paternal Parenting Behaviors

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants and Procedure

2.2. Measures

2.2.1. ADHD Symptoms

2.2.2. Antisocial Behavior

2.2.3. Parents’ Positive Behaviors

2.2.4. Parents’ Negative Behaviors

2.3. Analyses

3. Results

3.1. Descriptive Statistics

3.2. Mothers’ Positive and Negative Parenting Behaviors as Moderators of the Association between ADHD Symptoms and Antisocial Behavior

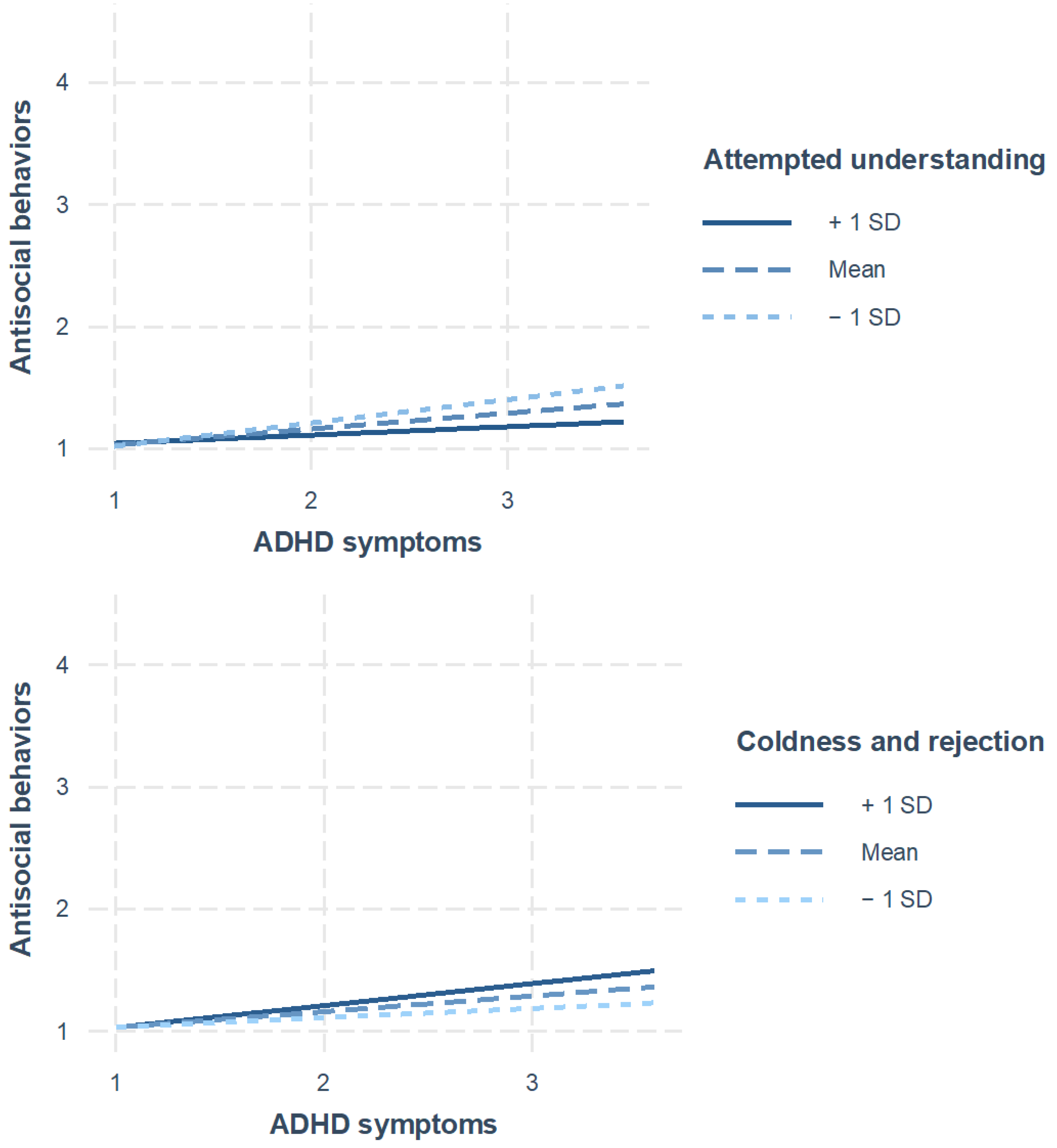

3.3. Fathers’ Positive and Negative Parenting Behaviors as Moderators of the Link between ADHD Symptoms and Antisocial Behavior

4. Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th ed.; American Psychiatric Publishing: Arlington, VA, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Schilling, C.M.; Walsh, A.; Yun, I. ADHD and criminality: A primer on the genetic, neurobiological, evolutionary, and treatment literature for criminologists. J. Crim. Justice 2011, 39, 3–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, E.; Sonuga-Barke, E. Disorders of attention and activity. In Rutter’s Textbook of Child Psychiatry, 5th ed.; Rutter, M., Bishop, D., Pine, D., Scott, S., Stevenson, J., Taylor, E., Thapar, A., Eds.; Wiley Blackwell: Oxford, UK, 2008; pp. 521–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Retz, W.; Ginsberg, Y.; Turner, D.; Barra, S.; Retz-Junginger, P.; Larsson, H.; Asherson, P. Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD), antisociality and delinquent behavior over the lifespan. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 2021, 120, 236–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fazel, S.; Doll, H.; Långström, N. Mental disorders among adolescents in juvenile detention and correctional facilities: A systematic review and meta-regression analysis of 25 surveys. J. Am. Acad. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 2008, 47, 1010–1019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baggio, S.; Fructuoso, A.; Guimaraes, M.; Fois, E.; Golay, D.; Heller, P.; Perroud, N.; Aubry, C.; Young, S.; Delessert, D.; et al. Prevalence of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder in detention settings: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Front. Psychiatry 2018, 9, 331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohr-Jensen, C.; Steinhausen, H.C. A meta-analysis and systematic review of the risks associated with childhood attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder on long-term outcome of arrests, convictions, and incarcerations. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 2016, 48, 32–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Lorenzo, R.; Balducci, J.; Poppi, C.; Arcolin, E.; Cutino, A.; Ferri, P.; D’Amico, R.; Filippini, T. Children and adolescents with ADHD followed up to adulthood: A systematic review of long-term outcomes. Acta Neuropsychiatr. 2021, 33, 283–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fletcher, J.; Wolfe, B. Long-term consequences of childhood ADHD on criminal activities. J. Ment. Health Policy Econ. 2009, 12, 119–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Unnever, J.D.; Cullen, F.T.; Agnew, R. Why is “bad” parenting criminogenic? Implications from rival theories. J. Juv. Justice 2006, 4, 3–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nikolas, M.A.; Burt, S.A. Genetic and environmental influences on ADHD symptom dimensions of inattention and hyperactivity: A meta-analysis. J. Aborm. Psychol. 2010, 119, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bornalova, M.A.; Lahey, B.B.; Van Hulle, C.A.; Grych, H.D.; Hipwell, A.; Stepp, S.; Waldman, I.D. Genetic and environmental influences on aggression in 9- to 10-year-old twins. J. Abnorm. Psychol. 2010, 119, 834–846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steinberg, L.; Blatt-Eisengart, I.; Cauffman, E. Patterns of competence and adjustment among adolescents from authoritative, authoritarian, indulgent, and neglectful homes: A replication in a sample of serious juvenile offenders. J. Adolesc. Res. 2006, 16, 47–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pinquart, M. Associations of parenting dimensions and styles with externalizing problems of children and adolescents: An updated meta-analysis. Dev. Psychol. 2017, 53, 873–932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hoeve, M.; Dubas, J.S.; Eichelsheim, V.I.; Van der Laan, P.H.; Smeenk, W.; Gerris, J.R. The relationship between parenting and delinquency: A meta-analysis. J. Abnorm. Child Psychol. 2009, 37, 749–775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Benson, M.J.; Buehler, C. Family process and peer deviance influences on adolescent aggression: Longitudinal effects across early and middle adolescence. Child Dev. 2012, 83, 1213–1228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thapar, A.; Van den Bree, M.; Fowler, T.; Langley, K.; Whittinger, N. Predictors of antisocial behaviour in children with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. Eur. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 2006, 15, 118–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patterson, G.R. The Early Development of Coercive Family Process; Castalia Publishing Company: Eugene, OR, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Walther, C.A.; Cheong, J.; Molina, B.S.; Pelham, W.E., Jr.; Wymbs, B.T.; Belendiuk, K.A.; Pedersen, S.L. Substance use and delinquency among adolescents with childhood ADHD: The protective role of parenting. Psychol. Addict. Behav. 2012, 26, 585–598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, P.; Schlomer, G.L.; Lippold, M.A. Mothering versus fathering? Positive parenting versus negative parenting? Their relative importance in predicting adolescent aggressive behavior: A longitudinal comparison. Dev. Psychol. 2023, 59, 69–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Heel, M.; Bijttebier, P.; Colpin, H.; Goossens, L.; Van den Noortgate, W.; Verschueren, K.; Van Leeuwen, K. Adolescent-parent discrepancies in perceptions of parenting: Associations with adolescent externalizing problem behavior. J. Child Fam. Stud. 2019, 28, 3170–3182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swanson, J.M.; Kraemer, H.C.; Hinshaw, S.P.; Arnold, L.E.; Conners, C.K.; Abikoff, H.B.; Clevenger, W.; Davies, M.; Elliott, G.R.; Greenhill, L.L.; et al. Clinical relevance of the primary findings of the MTA: Success rates based on severity of ADHD and ODD symptoms at the end of treatment. J. Am. Acad. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 2001, 40, 168–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bussing, R.; Fernandez, M.; Harwood, M.; Hou, W.; Garvan, C.W.; Eyberg, S.M.; Swanson, J.M. Parent and teacher SNAP-IV ratings of Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder symptoms: Psychometric properties and normative ratings from a school district sample. Assessment 2008, 15, 317–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haynie, D.L. Delinquent peers revisited: Does network structure matter? Am. J. Sociol. 2001, 106, 1013–1057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magnusson, D.; Dunér, A.; Zetterblom, G. Adjustment: A Longitudinal Study; Wiley: New York, NY, USA, 1975. [Google Scholar]

- Tilton-Weaver, L.; Kerr, M.; Pakalniskeine, V.; Tokic, A.; Salihovic, S.; Stattin, H. Open up or close down: How do parental reactions affect youth information management? J. Adolesc. 2010, 33, 333–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Persson, A.; Kerr, M.; Stattin, H. Staying in or moving away from structured activities: Explanations involving parents and peers. Dev. Psychol. 2007, 43, 197–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hlavac, M. Stargazer: Well-Formatted Regression and Summary Statistics Tables. R Package Version 5.2.3: Bratislava, Slovakia. 2022. Available online: https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=stargazer (accessed on 29 August 2024).

- Long, J.A. Interactions: Comprehensive, User-Friendly Toolkit for Probing Interactions. R Package Version 1.2.0: Columbia, South Carolina, USA. 2024. Available online: https://cran.r-project.org/package=interactions (accessed on 29 August 2024).

- R Core Team. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing; R Foundation for Statistical Computing: Vienna, Austria, 2024; Available online: https://www.R-project.org/ (accessed on 29 August 2024).

- Kerr, M.; Stattin, H.; Pakalniskiene, V. Parents react to adolescent problem behaviors by worrying more and monitoring less. In What Can Parents Do?: New Insights into the Role of Parents in Adolescent Problem Behavior; Kerr, M., Stattin, H., Engels, R.C.M.E., Eds.; Wiley: New York, NY, USA, 2008; pp. 89–112. [Google Scholar]

- Tehrani, H.D.; Yamini, S. Personality traits and conflict resolution styles: A meta-analysis. Personal. Individ. Differ. 2020, 157, 109794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bornstein, M.H. Children’s parents. In Handbook of Child Psychology and Developmental Science: Ecological Settings and Processes, 7th ed.; Bornstein, M.H., Leventhal, T., Lerner, R.M., Eds.; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2015; Volume 4, pp. 55–134. [Google Scholar]

- Kerr, M.; Stattin, H. Parenting of adolescents: Action or reaction? In Children’s Influence on Family Dynamics: The Neglected Side of Family Relationships; Crouter, A.C., Booth, A., Eds.; Lawrence Erlbaum: Mahwah, NJ, USA, 2003; pp. 121–151. [Google Scholar]

- Hoeve, M.; Dubas, J.S.; Gerris, J.R.; Van der Laan, P.H.; Smeenk, W. Maternal and paternal parenting styles: Unique and combined links to adolescent and early adult delinquency. J. Adolesc. 2011, 34, 813–827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variable | M | SD | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Antisocial behavior | 1.15 | 0.33 | |||||||||

| 2. ADHD | 1.83 | 0.52 | 0.23 ** | ||||||||

| 3. Attempted understanding (m) | 2.42 | 0.44 | −0.11 ** | −0.15 ** | |||||||

| 4. Attempted understanding (f) | 2.32 | 0.50 | −0.14 ** | −0.15 ** | 0.66 ** | ||||||

| 5. Warmth (m) | 2.46 | 0.44 | −0.13 ** | −0.13 ** | 0.50 ** | 0.34 ** | |||||

| 6. Warmth (f) | 2.34 | 0.50 | −0.13 ** | −0.07 ** | 0.31 ** | 0.49 ** | 0.64 ** | ||||

| 7. Angry outbursts (m) | 1.63 | 0.57 | 0.17 ** | 0.19 ** | −0.15 ** | −0.10 ** | −0.28 ** | −0.20 ** | |||

| 8. Angry outbursts (f) | 1.62 | 0.58 | 0.12 ** | 0.17 ** | −0.06 * | −0.11 ** | −0.13 ** | −0.28 ** | 0.47 ** | ||

| 9. Coldness and rejection (m) | 1.35 | 0.45 | 0.15 ** | 0.17 ** | −0.23 ** | −0.19 ** | −0.27 ** | −0.15 ** | 0.59 ** | 0.36 ** | |

| 10. Coldness and rejection (f) | 1.38 | 0.48 | 0.16 ** | 0.12 ** | −0.17 ** | −0.19 ** | −0.18 ** | −0.28 ** | 0.38 ** | 0.62 ** | 0.60 ** |

| Dependent Variable: | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Antisocial Behaviors | ||||

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | |

| ADHD symptoms | 0.29 ** | 0.35 ** | −0.07 | −0.10 |

| (0.11) | (0.11) | (0.06) | (0.07) | |

| Attempted understanding | 0.05 | |||

| (0.08) | ||||

| Attempted understanding × ADHD symptoms | −0.06 | |||

| (0.04) | ||||

| Warmth | 0.11 | |||

| (0.08) | ||||

| Warmth × ADHD symptoms | −0.09 * | |||

| (0.04) | ||||

| Angry outbursts | −0.12 | |||

| (0.07) | ||||

| Angry outbursts × ADHD symptoms | 0.11 ** | |||

| (0.04) | ||||

| Coldness and rejection | −0.22 ** | |||

| (0.09) | ||||

| Coldness and rejection × ADHD symptoms | 0.17 ** | |||

| (0.05) | ||||

| Observations | 768 | 760 | 777 | 780 |

| R2 | 0.07 | 0.07 | 0.09 | 0.08 |

| Adjusted R2 | 0.06 | 0.06 | 0.08 | 0.08 |

| Dependent Variable: | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Antisocial Behaviors | ||||

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | |

| ADHD symptoms | 0.41 ** | 0.31 ** | 0.06 | −0.03 |

| (0.10) | (0.10) | (0.06) | (0.07) | |

| Attempted understanding | 0.15 | |||

| (0.08) | ||||

| Attempted understanding × ADHD symptoms | −0.12 ** | |||

| (0.04) | ||||

| Warmth | 0.08 | |||

| (0.08) | ||||

| Warmth × ADHD symptoms | −0.08 | |||

| (0.04) | ||||

| Angry outbursts | −0.04 | |||

| (0.07) | ||||

| Angry outbursts × ADHD symptoms | 0.05 | |||

| (0.04) | ||||

| Coldness and rejection | −0.12 | |||

| (0.08) | ||||

| Coldness and rejection × ADHD symptoms | 0.11 * | |||

| (0.04) | ||||

| Observations | 748 | 738 | 751 | 753 |

| R2 | 0.08 | 0.07 | 0.07 | 0.08 |

| Adjusted R2 | 0.08 | 0.06 | 0.07 | 0.08 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Salihovic, S.; Zhao, X.; Glatz, T. The Association between ADHD Symptoms and Antisocial Behavior: Differential Effects of Maternal and Paternal Parenting Behaviors. Youth 2024, 4, 1405-1416. https://doi.org/10.3390/youth4040089

Salihovic S, Zhao X, Glatz T. The Association between ADHD Symptoms and Antisocial Behavior: Differential Effects of Maternal and Paternal Parenting Behaviors. Youth. 2024; 4(4):1405-1416. https://doi.org/10.3390/youth4040089

Chicago/Turabian StyleSalihovic, Selma, Xiang Zhao, and Terese Glatz. 2024. "The Association between ADHD Symptoms and Antisocial Behavior: Differential Effects of Maternal and Paternal Parenting Behaviors" Youth 4, no. 4: 1405-1416. https://doi.org/10.3390/youth4040089

APA StyleSalihovic, S., Zhao, X., & Glatz, T. (2024). The Association between ADHD Symptoms and Antisocial Behavior: Differential Effects of Maternal and Paternal Parenting Behaviors. Youth, 4(4), 1405-1416. https://doi.org/10.3390/youth4040089