Why Not All Three? Combining the Keller, Rhodes, and Spencer Models Two Decades Later to Equitably Support the Health and Well-Being of Minoritized Youth in Mentoring Programs

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Process

3. Who We Are and Our Guiding Values

4. Centering the Pursuit of Social Justice and Recognition of Structural Oppression

4.1. Utilizing Healing-Centered Engagement

A healing centered approach to addressing trauma requires a different question that moves beyond “what happened to you” to “what’s right with you” and views those exposed to trauma as agents in the creation of their own well-being rather than victims of traumatic events. (p. 3)

Thriving entails the engagement of one’s unique talents, interests, and/or aspirations. In this lies the assumption of one’s self awareness of [their] uniqueness and the opportunities to purposefully manifest them. Through such engagement, one might be thought of as actively working toward fulfilling [their] full potential. (p. 2).

when people advocate for policies and opportunities that address causes of trauma, such as lack of access to mental health, these activities contribute to a sense of purpose, power and control over life situations. All of these are ingredients necessary to restore well-being and healing. (p. 4)

4.2. Valuing a Strengths-Based Approach with Young People

Developmentally effective proximal processes are not unidirectional; there must be influence in both directions. For interpersonal interaction, this means that initiatives do not come from one side only; there must be some degree of reciprocity in the exchange. [46] (p. 798)

4.3. Recognizing Social Capital and All Forms of Community Cultural Wealth

5. How the Strengths of the Previous Models Complement One Another

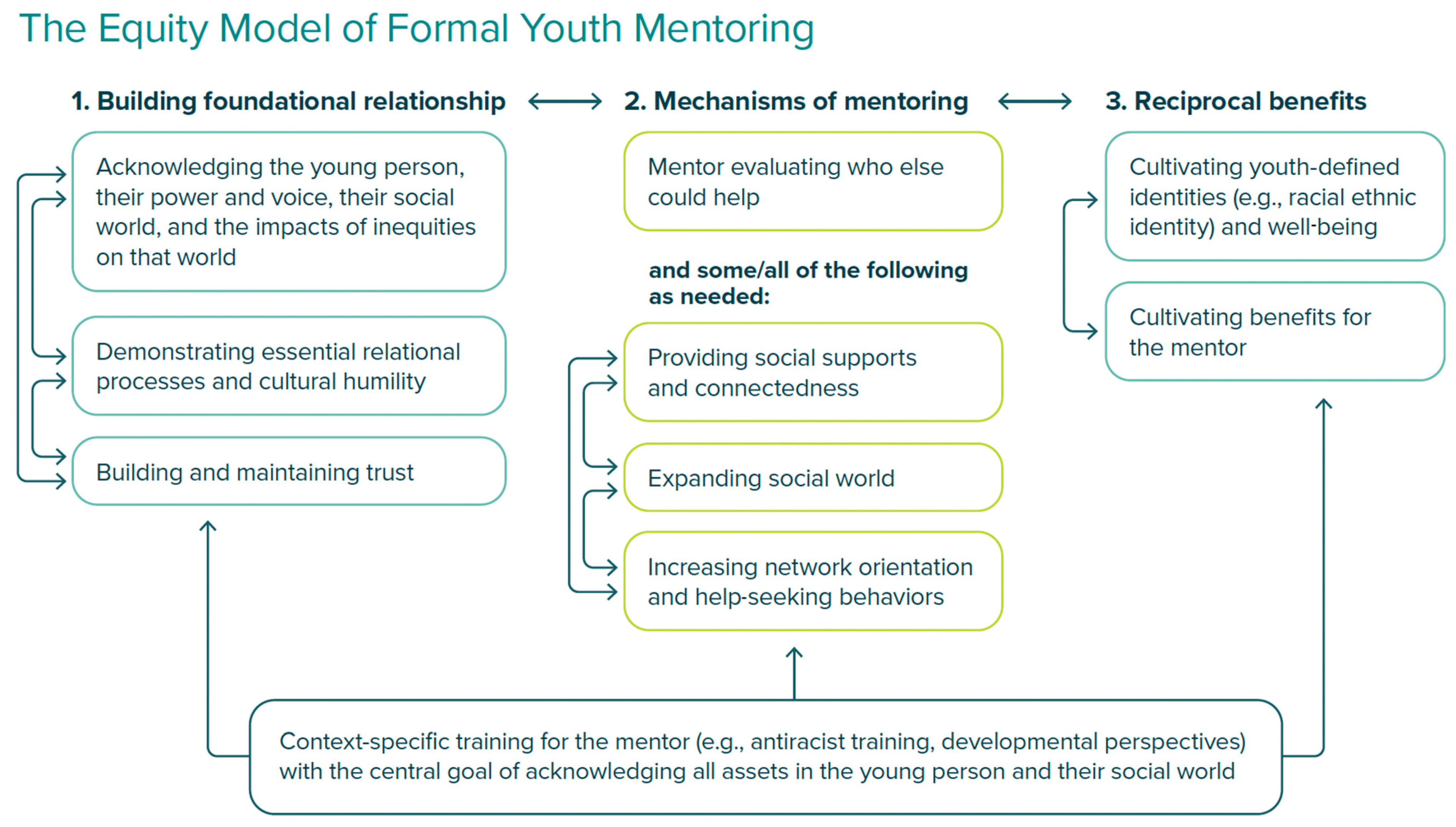

6. The Equity Model of Formal Youth Mentoring

6.1. Building a Foundational Relationship

6.2. Acknowledging the Young Person, Their Power and Voice, and Their Social World

6.3. Demonstrating Essential Relational Processes and Cultural Humility

6.4. Building and Maintaining Trust

6.5. Mechanisms of Mentoring

6.6. Providing Social Support and Connectedness

6.7. Expanding Social World

6.8. Increasing Network Orientation and Help-Seeking Behaviors

7. Reciprocal Benefits

7.1. Cultivating Youth-Defined Identities and Well-Being

7.2. Mentor Benefits

7.3. Context-Specific Support

8. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Raposa, E.B.; Rhodes, J.; Stams GJ, J.M.; Card, N.; Burton, S.; Schwartz, S.; Sykes LA, Y.; Kanchewa, S.; Kupersmidt, J.; Hussain, S. The effects of youth mentoring programs: A meta-analysis of outcome studies. J. Youth Adolesc. 2019, 48, 423–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DuBois, D.L.; Holloway, B.E.; Valentine, J.C.; Cooper, H. Effectiveness of mentoring programs for youth: A meta-analytic review. Am. J. Community Psychol. 2002, 30, 157–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Race and National Origin. National Institutes of Health. Available online: https://www.nih.gov/nih-style-guide/race-national-origin#:~:text=Minoritized%20populations%20are%20groups%20that,persecuted%20because%20of%20systemic%20oppression (accessed on 25 August 2024).

- Russell, S.T.; Campen, K.V. Diversity and inclusion in youth development: What we can learn from marginalized young people. J. Youth Dev. 2011, 6, 94–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Jones, K.; Parra-Cardona, R.; Sánchez, B.; Vohra-Gupta, S.; Franklin, C. All things considered: Examining mentoring relationships between White mentors and Black youth in community-based youth mentoring programs. Child Youth Care Forum 2023, 52, 997–1017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, K.; Parra-Cardona, R.; Sánchez, B.; Vohra-Gupta, S.; Franklin, C. Motivations, program support, and personal growth: Mentors perspectives on the reciprocal benefits of cross-racial mentoring relationships with Black youth. Child. Youth Serv. Rev. 2023, 150, 106996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, C.L.; Sánchez, B. Mentoring relationship quality profiles and their association with urban, low-income youth’s academic outcomes. Youth Soc. 2019, 51, 443–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hurd, N. Promoting positive development among racially and ethnically marginalized youth: Advancing a novel model of natural mentoring. Annu. Rev. Clin. Psychol. 2024, 20, 259–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spencer, R. Understanding the Mentoring Process between Adolescents and Adults. Youth Soc. 2006, 37, 287–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keller, T.E. A systemic model of the youth mentoring intervention. J. Prim. Prev. 2005, 26, 169–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rhodes, J.; DuBois, D. Mentoring Relationships and Programs for Youth. Curr. Dir. Psychol. Sci. 2008, 17, 254–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gowdy, G.; Jones, K.; Griffith, A.N. Youth mentoring as a means of supporting mental health for minoritized youth: A reflection on three theoretical frameworks 20 years later. Youth 2024, 4, 1211–1223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alexander, M. The New Jim Crow; The New Press: New York, NY, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Delgado, R.; Stefancic, J. Critical Race Theory: An Introduction; NYU Press: New York, NY, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Jones, J.M. Prejudice and Racism, 2nd ed.; McGraw-Hill: New York, NY, USA, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Young, I.M. Five faces of oppression. In The Community Development Reader; DeFilippis, J., Saegert, S., Eds.; Princeton University: Princeton, NJ, USA, 2014; pp. 346–355. [Google Scholar]

- Gaylord-Harden, N.; Barbarin, O.; Tolan, P.; Murry, V.; Gaylord-Harden, N. Understanding development of African American boys and young men: Moving from risks to positive youth development. Am. Psychol. 2018, 73, 753–767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jones-Eversley, S.; Adedoyin, A.C.; Robinson, M.A.; Moore, S.E. Protesting Black inequality: A commentary on the Civil Rights Movement and Black Lives Matter. J. Community Pract. 2017, 25, 309–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stevenson, H.C. Dueling narratives: Racial socialization and literacy as triggers for re-humanizing African American boys, young men, and their families. In Boys and Men in African American Families, National Symposium on Family Issues 7; Burton, L., Burton, D., McHale, S.M., King, V., Van Hook, J., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2016; pp. 55–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Travis, R.; Leech, T. Empowerment-based positive youth development: A new understanding of healthy development for African American youth. J. Res. Adolesc. 2014, 24, 93–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edwards, K.M.; Scheer, J.R.; Mauer, V.A. Informal and formal mentoring of sexual and gender minority youth: A systematic review. Sch. Soc. Work. J. 2022, 47, 37–71. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson, D.; Gastic, B. Natural mentoring in the lives of sexual minority youth. J. Community Psychol. 2015, 43, 395–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaufman, M.R.; Lin, C.; Levine, D.; Salcido, M.; Casella, A.; Simon, J.; DuBois, D.L. The formation and benefits of natural mentoring for African American sexual and gender minority adolescents: A qualitative study. J. Adolesc. Res. 2024, 39, 53–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cunningham, M.; Mulser, R.M.; Scott, K.; Yates, A. African American adolescents speak: The meaning of racial identity in the relation between individual race-related stress and depressive symptoms. In Handbook of Children and Prejudice; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2019; pp. 533–550. [Google Scholar]

- Huynh, V.; Fuligni, A. Discrimination hurts: The academic, psychological, and physical well-being of adolescents. J. Res. Adolesc. 2010, 20, 916–941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Priest, N.; Paradies, Y.; Trenerry, B.; Truong, M.; Karlsen, S.; Kelly, Y. A systematic review of studies examining the relationship between reported racism and health and wellbeing for children and young people. Soc. Sci. Med. 2013, 95, 115–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seaton, E.K.; Douglass, S. School diversity and racial discrimination among African-American adolescents. Cult. Divers. Ethn. Minor. Psychol. 2014, 20, 156–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lo, C.C.; Hopson, L.M.; Simpson, G.M.; Cheng, T.C. Racial/ethnic differences in emotional health: A longitudinal study of immigrants’ adolescent children. Community Ment. Health J. 2017, 53, 92–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pascoe, E.; Richman, L. Perceived discrimination and health: A meta-analytic review. Psychol. Bull. 2009, 135, 531–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Neblett, E.W., Jr.; Rivas-Drake, D.; Umaña-Taylor, A.J. The promise of racial and ethnic protective factors in promoting ethnic minority youth development. Child Dev. Perspect. 2012, 6, 295–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rivas-Drake, D.; Seaton, E.; Markstrom, C.; Quintana, S.; Syed, M.; Lee, R.; Schwartz, S.; Umaña-Taylor, A.; French, S.; Yip, T. Ethnic and racial identity in adolescence: Implications for psychosocial, academic, and health outcomes. Child Dev. 2014, 85, 40–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gordon, D.M.; Iwamoto, D.; Ward, N.; Potts, R.; Boyd, E. Mentoring urban Black middle-school male students: Implications for academic achievement. J. Negro Educ. 2009, 78, 277–289. [Google Scholar]

- Hurd, N.M.; Sánchez, B.; Zimmerman, M.A.; Caldwell, C.H. Natural mentors, racial identity, and educational attainment among African American adolescents: Exploring pathways to success. Child Dev. 2012, 83, 1196–1212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaplan, C.P.; Turner, S.G.; Piotrkowski, C.; Silber, E. Club Amigas: A promising response to the needs of adolescent Latinas. Child Fam. Soc. Work. 2009, 14, 213–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez, B.; Anderson, A.J.; Carter, J.S.; Mroczkowski, A.L.; Monjaras-Gaytan, L.Y.; DuBois, D.L. Helping me helps us: The role of natural mentors in the ethnic identity and academic outcomes of Latinx adolescents. Dev. Psychol. 2020, 56, 208–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez, B.; Hurd, N.M.; Neblett, E.W.; Vaclavik, D. Mentoring for Black male youth: A systematic review of the research. Adolesc. Res. Rev. 2018, 3, 259–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albright, J.; Hurd, N.; Hussain, S. Applying a social justice lens to youth mentoring: A Review of the literature and recommendations for practice. Am. J. Community Psychol. 2017, 59, 363–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, B.; Bogat, G.; Duffy, N. Gender in mentoring relationships. In Handbook of Youth Mentoring; DuBois, D.L., Karcher, M.J., Eds.; SAGE Publications, Inc.: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2014; pp. 159–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwartz, S.E.O.; Rhodes, J.E. From treatment to empowerment: New approaches to youth mentoring. Am. J. Community Psychol. 2016, 58, 150–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weiston-Serdan, T. Critical Mentoring: A Practical Guide; Stylus Publishing, LLC.: Sterling, VA, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Ginwright, S. The future of healing: Shifting from trauma-informed care to healing centered engagement. Occas. Pap. 2018, 25, 25–32. Available online: https://kinshipcarersvictoria.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/08/OP-Ginwright-S-2018-Future-of-healing-care.pdf (accessed on 12 June 2024).

- Caldwell, L.L.; Witt, P.A. Ten principles of youth development. In Youth Development: Principles and Practices in Out-of-School Time Settings; Witt, P.A., Caldwell, L.L., Eds.; 1807 North Federal Drive, 61801; Sagamore-Venture: Champaign, IL, USA, 2018; pp. 1–25. [Google Scholar]

- Garringer, M.; Benning, C. Who Mentored You? A Study Examining the Role Mentors Have Played in the Lives of Americans Over the Last Half Century; MENTOR: National Mentoring Partnership: Boston, MA, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Garringer, M.; McQuillin, S.; McDaniel, H. Examining Youth Mentoring Services Across America: Findings from the 2016 National Mentoring Program Survey; MENTOR: National Mentoring Partnership: Boston, MA, USA. 2017. Available online: https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED605698.pdf (accessed on 25 August 2024).

- Saleebey, D. The Strengths Perspective in Social Work Practice: Power in the People; Longman: London, UK, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Bronfenbrenner, U.; Morris, P.A. The bioecological model of human development. In Handbook of Child Psychology, 6th ed.; Lerner, R., Damon, W., Eds.; Theoretical models of human development; John Wiley & Sons Inc.: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2006; Volume 1, pp. 793–828. [Google Scholar]

- White, M.; Glick, J. Generation Status, Social Capital, and the Routes out of High School. Sociol. Forum 2000, 15, 671–691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phelan, P.; Davidson, A.L.; Yu, H.C. Students’ multiple worlds: Navigating the borders of family, peer, and school cultures. In Cultural Diversity: Implications for Education; Phelan, P., Davidson, A.L., Eds.; Teachers College Press: New York, NY, USA, 1991; pp. 52–88. [Google Scholar]

- Stanton-Salazar, R.D. A social capital framework for the study of institutional agents and their role in the empowerment of low-status students and youth. Youth Soc. 2011, 43, 1066–1109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erickson, L.D.; McDonald, S.; Elder, G.H. Informal mentors and education: Complementary or compensatory resources? Sociol. Educ. 2009, 82, 344–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ewart, I. White teachers as a risk factor in the healthy development of black youth. Moja Interdiscip. J. Afr. Stud. 2020, 1, 41–50. [Google Scholar]

- Riddle, T.; Sinclair, S. Racial disparities in school-based disciplinary actions are associated with county-level rates of racial bias. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2019, 116, 8255–8260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steketee, A.; Williams, M.T.; Valencia, B.T.; Printz, D.; Hooper, L.M. Racial and language microaggressions in the school ecology. Perspect. Psychol. Sci. 2021, 16, 1075–1098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yosso, T.J. Whose culture has capital? A critical race theory discussion of community cultural wealth. Race Ethn. Educ. 2005, 8, 69–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rhodes, J. A model of youth mentoring. In Handbook of Youth Mentoring; DuBois, D.L., Karcher, M.J., Eds.; SAGE: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2005; pp. 30–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spencer, R. (Boston University, Boston, MA, USA). Personal communication, 17 March 2023.

- Bruce, M.; Bridgeland, J. The Mentoring Effect: Young People’s Perspectives on the Outcomes and Availability of Mentoring; Civic Enterprises with Hart Research Associates for MENTOR: The National Mentoring Partnership: Boston, MA, USA. 2014. Available online: https://www.semanticscholar.org/paper/The-Mentoring-Effect%3A-Young-People%27s-Perspectives-A-Bruce-Bridgeland/42544a3fc5390a18d33d7f8f688f2697f8cd344c (accessed on 25 August 2024).

- Meltzer, A.; Muir, K.; Craig, L. The role of trusted adults in young people’s social and economic lives. Youth Soc. 2016, 50, 575–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, K.; Parra-Cardona, R.; Sánchez, B.; Vohra-Gupta, S.; Franklin, C. Forming an alliance: Mentor’s perspectives on the role of family and social networks in cross-racial mentoring relationships with Black youth. J. Ethn. Cult. Divers. Soc. Work. 2023, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitchell Dove, L. Black Youths’ Perspectives: Importance of Family and Caregiver Involvement in the Mentor-Mentee Relationship. Healthcare 2022, 10, 2181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gowdy, G.; Gillis, T. Impacts of core and capital informal mentoring on minoritized youth: Use of a quasi-experimental design. Poster Presentation Given at the Society for Social Work and Research, Anaheim, CA, USA. 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Loury, L. All in the extended family: Effects of grandparents, aunts, and uncles on educational attainment. Am. Econ. Rev. 2006, 96, 275–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scott, E.D., Jr.; Deutsch, N.L. Conferring kinship: Examining fictive kinship status in a Black adolescent’s natural mentoring relationship. J. Black Psychol. 2021, 47, 317–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Young, A.A. The redeemed old head: Articulating a sense of public self and social purpose. Symb. Interact. 2007, 30, 347–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fisher-Borne, M.; Cain, J.M.; Martin, S.L. From mastery to accountability: Cultural humility as an alternative to cultural competence. Soc. Work. Educ. 2015, 34, 165–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foronda, C. A theory of cultural humility. J. Transcult. Nurs. 2020, 31, 7–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spencer, R.; Pryce, J.; Barry, J.; Walsh, J.; Basualdo-Delmonico, A. Deconstructing empathy: A qualitative examination of mentor perspective-taking and adaptability in youth mentoring relationships. Child. Youth Serv. Rev. 2020, 114, 105043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rhodes, J. The critical ingredient: Caring youth-staff relationships in after-school settings. New Dir. Youth Dev. 2004, 2004, 145–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rhodes, J. Stand by Me: The Risks and Rewards of Mentoring Today’s Youth; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez, B.; Pryce, J.; Silverthorn, N.; Deane, K.L.; DuBois, D.L. Do mentor support for ethnic–racial identity and mentee cultural mistrust matter for girls of color? A preliminary investigation. Cult. Divers. Ethn. Minor. Psychol. 2019, 25, 505–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- House, J.S. Work Stress and Social Support; Addison-Wesley: Boston, MA, USA, 1981. [Google Scholar]

- Gottlieb, B.H.; Bergen, A.E. Social support concepts and measures. J. Psychosom. Res. 2010, 69, 511–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Greeson JK, P.; Usher, L.; Grinstein-Weiss, M. One adult who is crazy about you: Can natural mentoring relationships increase assets among young adults with and without foster care experience? Child. Youth Serv. Rev. 2010, 32, 565–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sterrett, E.M.; Jones, D.J.; McKee, L.G.; Kincaid, C. Supportive non-parental adults and adolescent psychosocial functioning: Using social support as a theoretical framework. Am. J. Community Psychol. 2011, 48, 284–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wentzel, K.R.; Russell, S.; Baker, S. Emotional support and expectations from parents, teachers, and peers predict adolescent competence at school. J. Educ. Psychol. 2016, 108, 242–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sullivan, P.J.; Larson, R.W. Connecting youth to high-resource adults: Lessons from effective youth programs. J. Adolesc. Res. 2010, 25, 99–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hagler, M.; Rhodes, J. The long-term impact of natural mentoring relationships: A counter-factual analysis. Am. J. Community Psychol. 2018, 62, 175–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chu, P.; Saucier, D.; Hafner, E. Meta-Analysis of the relationships between social support and well-being in children and adolescents. J. Soc. Clin. Psychol. 2010, 29, 624–645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brewster, A.; Bowen, G. Teacher support and the school engagement of Latino middle and high school students at risk of school failure. Child Adolesc. Soc. Work. J. 2004, 21, 47–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crul, M.; Schneider, J.; Keskiner, E.; Lelie, F. The multiplier effect: How the accumulation of cultural and social capital explains steep upward social mobility of children of low-educated immigrants. Ethn. Racial Stud. 2017, 40, 321–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chavous, T.; Rivas-Drake, D.; Smalls, C.; Griffin, T.; Cogburn, C. Gender matters, too: The influences of school racial discrimination and racial identity on academic engagement outcomes among African American adolescents. Dev. Psychol. 2008, 44, 637–654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cross, W.; Seaton, E.; Yip, T.; Lee, R.; Rivas, D.; Gee, G.; Roth, W.; Ngo, B. Identity work: Enactment of racial-ethnic identity in everyday life. Identity 2017, 17, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leath, S.; Mathews, C.; Harrison, A.; Chavous, T. Racial identity, racial discrimination, and classroom engagement outcomes among Black girls and boys in predominantly Black and predominantly White school districts. Am. Educ. Res. J. 2019, 56, 1318–1352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oyserman, D. Identity-based motivation: Implications for action-readiness, procedural-readiness, and consumer behavior. J. Consum. Psychol. 2009, 19, 250–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peifer, J.; Lawrence, E.; Williams, J.; Leyton-Armakan, J. The culture of mentoring: Ethnocultural empathy and ethnic identity in mentoring for minority girls. Cult. Divers. Ethn. Minor. Psychol. 2016, 22, 440–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Umaña-Taylor, A.; Quintana, S.; Lee, R.; Cross, W.; Rivas-Drake, D.; Schwartz, S.; Syed, M.; Yip, T.; Seaton, E. Ethnic and racial identity during adolescence and into young adulthood: An integrated conceptualization. Child Dev. 2014, 85, 21–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Velez, G.; Spencer, M.B. Phenomenology and intersectionality: Using PVEST as a frame for adolescent identity formation amid intersecting ecological systems of inequality. New Dir. Child Adolesc. Dev. 2018, 2018, 75–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mirpuri, S.; Ray, C.; Hassan, A.; Aladin, M.; Wang, Y.; Yip, T. Ethnic/Racial identity as a moderator of the relationship between discrimination and adolescent outcomes. In Handbook of Children and Prejudice: Integrating Research, Practice, and Policy; Fitzgerald, H., Johnson, D., Qin, D., Villarruel, F., Norder, J., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2019; pp. 477–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Apugo, D.; Castro, A.J.; Dougherty, S.A. Taught in the matrix: A review of Black girls’ experiences in U.S. schools. Rev. Educ. Res. 2023, 93, 559–593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Epstein, R.; Blake, J.; González, T. Girlhood Interrupted: The Erasure of Black Girls’ Childhood; Georgetown Law Center on Poverty and Inequality. 2017. Available online: https://genderjusticeandopportunity.georgetown.edu/wp-content/uploads/2020/06/girlhood-interrupted.pdf (accessed on 25 August 2024).

- Griffith, A.N. “They do us wrong”: Bringing together Black adolescent girls’ voices on school staff’s differential treatment. J. Black Psychol. 2023, 49, 598–645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neal-Jackson, A. A meta-ethnographic review of the experiences of African American girls and young women in K–12 education. Rev. Educ. Res. 2018, 88, 508–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clonan-Roy, K.; Jacobs, C.E.; Nakkula, M.J. Towards a model of positive youth development specific to girls of color: Perspectives on development, resilience, and empowerment. Gend. Issues 2016, 33, 96–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ross, D.A.; Hinton, R.; Melles-Brewer, M.; Engel, D.; Zeck, W.; Fagan, L.; Herat, J.; Phaladi, G.; Imbago-Jácome, D.; Anyona, P.; et al. Adolescent well-being: A definition and conceptual framework. J. Adolesc. Health 2020, 67, 472–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christens, B.D.; Winn, L.T.; Duke, A.M. Empowerment and critical consciousness: A conceptual cross-fertilization. Adolesc. Res. Rev. 2016, 1, 15–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jemal, A. Critical consciousness: A critique and critical analysis of the literature. Urban Rev. 2017, 49, 602–626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heberle, A.E.; Rapa, L.J.; Farago, F. Critical consciousness in children and adolescents: A systematic review, critical assessment, and recommendations for future research. Psychol. Bull. 2020, 146, 525–551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gonzalez, M.; Kokozos, M.; Byrd, C.M.; McKee, K.E. Critical positive youth development: A framework for centering critical consciousness. J. Youth Dev. 2020, 15, 24–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, A.J.; Sánchez, B.; Meyer, G.; Sales, B.P. Supporting adults to support youth: An evaluation of two social justice trainings. J. Community Psychol. 2018, 46, 1092–1106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duron, J.; Williams-Butler, A.; Schmidt, A.; Colon, L. Mentors’ experiences of mentoring justice-involved adolescents: A narrative of developing cultural consciousness through connection. J. Community Psychol. 2020, 48, 2309–2325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meltzer, A.; Saunders, I. Cultivating supportive communities for young people: Mentor pathways into and following a youth mentoring program. Child. Youth Serv. Rev. 2020, 110, 104815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Worker, S.M.; Espinoza, D.M.; Kok, C.M.; Go, C.; Miller, J.C. Volunteer outcomes and impact: The contributions and consequences of volunteering in 4-H. J. Youth Dev. 2020, 15, 6–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez, B.; Anderson, A.J.; Weiston-Serdan, T.; Catlett, B.S. Anti-racism education and training for adult mentors who work with BIPOC adolescents. J. Adolesc. Res. 2021, 36, 686–716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malti, T.; Noam, G.G. Social-emotional development: From theory to practice. Eur. J. Dev. Psychol. 2016, 13, 652–665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noam, G.G.; Malti, T.; Karcher, M.J. Mentoring relationships in developmental perspective. In Handbook of Youth Mentoring; DuBois, D., Karcher, M.J., Eds.; SAGE Publications, Inc.: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2014; pp. 99–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brinegar, K.; Caskey, M.M. Developmental Characteristics of Young Adolescents: Research Summary. Association for Middle Level Education. 2022. Available online: https://www.amle.org/developmental-characteristics-of-young-adolescents/ (accessed on 25 August 2024).

- Busey, C.L.; Gainer, J. Arrested development: How This We Believe utilizes colorblind narratives and racialization to socially construct early adolescent development. Urban Rev. 2022, 54, 85–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harrison, L.M.; Hurd, E.; Brinegar, K.M. Exploring the convergence of developmentalism and cultural responsiveness. In Equity and Cultural Responsiveness in the Middle Grades; Brinegar, K.M., Harrison, L.M., Hurd, E., Eds.; Information Age Publishing: Charlotte, NC, USA, 2019; pp. 3–21. [Google Scholar]

- Karcher, M.J.; Sass, D.A.; Herrera, C.; DuBois, D.L.; Heubach, J.; Grossman, J.B. Pathways by which case managers’ match support influences youth mentoring outcomes: Testing the systemic model of youth mentoring. J. Community Psychol. 2023, 51, 3243–3264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spencer, R.; Gowdy, G.; Drew, A.L.; McCormack, M.J.; Keller, T.E. It takes a village to break up a match: A systemic analysis of formal youth mentoring relationship endings. Child Youth Care Forum 2020, 49, 97–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Jones, K.V.; Gowdy, G.; Griffith, A.N. Why Not All Three? Combining the Keller, Rhodes, and Spencer Models Two Decades Later to Equitably Support the Health and Well-Being of Minoritized Youth in Mentoring Programs. Youth 2024, 4, 1348-1363. https://doi.org/10.3390/youth4030085

Jones KV, Gowdy G, Griffith AN. Why Not All Three? Combining the Keller, Rhodes, and Spencer Models Two Decades Later to Equitably Support the Health and Well-Being of Minoritized Youth in Mentoring Programs. Youth. 2024; 4(3):1348-1363. https://doi.org/10.3390/youth4030085

Chicago/Turabian StyleJones, Kristian V., Grace Gowdy, and Aisha N. Griffith. 2024. "Why Not All Three? Combining the Keller, Rhodes, and Spencer Models Two Decades Later to Equitably Support the Health and Well-Being of Minoritized Youth in Mentoring Programs" Youth 4, no. 3: 1348-1363. https://doi.org/10.3390/youth4030085

APA StyleJones, K. V., Gowdy, G., & Griffith, A. N. (2024). Why Not All Three? Combining the Keller, Rhodes, and Spencer Models Two Decades Later to Equitably Support the Health and Well-Being of Minoritized Youth in Mentoring Programs. Youth, 4(3), 1348-1363. https://doi.org/10.3390/youth4030085