1. Introduction

Asian American (AsA) youth and emerging adults are the fastest-growing racial and ethnic population in the United States (U.S.) [

1]. In 2019, the immediate college enrollment rate for AsA high school graduates was 82% [

2], making up 11% of undergraduate students in the U.S. [

3]. However, this statistic suggesting successful attainment of higher education does not provide a holistic picture of AsA health and well-being. A closer investigation of the experiences of AsAs reveals higher rates of reported mental health concerns than their white counterparts [

4]. The World Health Organization defines mental health as “a state of mental well-being that enables people to cope with the stresses of life, realize their abilities, learn well and work well, and contribute to their community” [

5]. Various factors, such as pressure to uphold the “model minority” stereotype, stress due to academic expectations, difficulty navigating a multicultural world, and discrimination, have been linked to adverse mental health outcomes among AsA youth and emerging adults [

6]. Since the COVID-19 pandemic, AsA adolescents and young adults have experienced an increase in adverse mental health outcomes [

7]. Yet, research with AsA youth–and with AsAs more generally–remains limited [

8,

9].

The sparse mental health literature about AsA youth does provide a concerning picture of this vulnerable group. A national survey conducted by the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration found that across all AsA adult age groups, AsAs between 18 and 25 years old had the highest lifetime rates of experiencing a major depressive episode [

10]. In 2019, the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services Office of Minority Health reported that suicide was the leading cause of mortality among 15–24-year-old AsA youth [

4]. AsA college student mental health has been in decline as well; for example, 2013–2021 saw a 75% increase in depression, 74% increase in anxiety, 52% increase in eating disorders, and 25% increase in suicidal ideation [

11]. The same study found a 26% increase in the co-occurrence of depression, anxiety, eating disorders, or self-injury with suicidal ideation. Even more troubling is that these outcomes are trending upwards as mental health problems among AsA youth and young adults increase in frequency and severity, as evidenced by the serious increase in suicidality. One study [

12] found that in 2018, 22% of 18- and 19- year-old AsAs sampled reported suicidal ideation versus the national average of 11% among the same age group in 2017.

Compounding these mental health concerns, AsAs have lower rates of help-seeking than white students [

13] and the lowest help-seeking rates in comparison with other minoritized racial–ethnic groups [

14]. While the reasons for lower help-seeking are underexplored, AsA college students were less likely to know someone who has received mental health services or has been diagnosed with a mental health condition than their Black, white, and Latine counterparts [

15]. Mental health help-seeking is also stigmatized among AsAs [

13]. One study found that AsAs score higher on self-stigma and perceived interpersonal stigmatization for mental health help-seeking [

16]. About 75% of all lifetime cases of mental disorders have an onset by age 24 [

17]. The present study then, sets out to fill a perilous gap in understanding opportunities to improve services and increase buffers for this population made vulnerable by intersecting impacts of racialization. Finding effective ways to engage AsA youth and emerging adults in utilizing mental health care when needed is, therefore, critical in reducing the aforementioned disparities, and in order to do so, researchers must rigorously explore, design, and implement services that fit.

2. The Present Study

Mental health has been identified as needing critical public health intervention. AsAs generally, and college students particularly, have received precious little research attention, leaving the problem of disparate mental health outcomes poorly understood, hidden within aggregated data, and thus difficult to interrupt. The gap in scientific understanding extends to risk and protective factors, attitudes and understandings, and engagement and effective interventions, to name only some. As such, this study meets an urgent need to expand knowledge about how AsA college students conceptualize mental health. The present exploratory study asks the following question: What facilitates or hinders the mental health of AsA undergraduate students from a large public university in central Texas?

3. Methods

This study analyzed Photovoice data collected during the second phase of a sequential explanatory mixed methods study that aimed to understand the link between internalized racism (IR) and education outcomes, considering the role of psychosocial distress and critical consciousness (CC) [

18]. The first phase of the sequential explanatory mixed methods study involved collecting quantitative data through an electronic survey. Qualtrics software, Version May 2022 was used to survey a sample of AsA undergraduate students attending a large public university in central Texas. A causal model of IR as a predictor of academic achievement and persistence, considering the role of individual psychological distress and CC, was tested in an analytic sample of 294 AsA undergraduates. The second phase involved collecting qualitative data through semi-structured interviews and Photovoice data with a sub-sample (

n = 14) of survey respondents from May to June of 2022. The goal of the semi-structured interviews and Photovoice data was to extend understanding and provide nuance to the survey results obtained in the previous phase of the sequential explanatory mixed methods study.

3.1. Photovoice

Photovoice is a community-based participatory action research approach often used to engage minoritized populations through ethnographic techniques that combine documentary photography, critical dialogue, and lived experience [

19]. Photovoice initially had three primary goals: (1) to enable community members to record and reflect on their community’s strengths and challenges, (2) to promote critical dialogue and knowledge sharing through group discussions about photographs, and (3) to reach policymakers and the broader public about the community’s issues [

20]. Photovoice was selected because of its ability to emphasize strengths and allow AsA emerging adults to both identify their challenges with mental health and recognize the ways their cultural wealth can address those challenges [

21]. The Photovoice data include participant-produced photographs, captions, and an additional interview dedicated to discussing the photographs provided.

3.2. Sampling

Participants for the Photovoice arm (

n = 14) were purposively sampled from the qualitative phase (n = 162) of the study, composed of those who opted in from the quantitative phase (N = 294), which includes all survey respondents. Participants who joined the qualitative phase and scored either high on the Colonial Mentality Scale (CMS) [

22], an assessment tool used to measure internalized racism, or low on the Short Critical Consciousness Scale (CCS-S) [

23] were invited to join the Photovoice arm of the study. Additionally, participants were purposively sampled to ensure a mix of genders. A total of 47 participants were invited: 28 participants expressed interest, and 19 participants accepted the invitation and were scheduled, 4 of whom did not complete their interviews despite offers to reschedule. A total of 15 participants were interviewed, but 1 participant was not included in the analytical sample because it was later discovered that they were not part of the final analytical sample for the first phase of the study (i.e., survey data collection); thus, we only analyzed interview and Photovoice data from the 14 participants who were also part of the analytical sample from the first phase of the study.

3.3. Interview Process

All interviews were conducted virtually on the Zoom platform. Participants received, completed, signed, and returned consent forms in advance via email. The consent process included participants granting permission to have their photographs used for scholarly dissemination such as publications, community art exhibits, and presentations. Participants were asked to take 1–2 photographs that best represented (1) educational experiences as an AsA student at the University of Texas at Austin (UT); (2) campus climate; (3) mental and physical health; and (4) recommendations to improve AsA lives. The current study analyzes the Photovoice data gathered for the third prompt about mental and physical health. Participants uploaded their photos and captions through Qualtrics via a secure link before their interview session. The interview was guided by an adapted version of Hussey’s PHOTO framework [

24]. Discussion of the photos typically lasted between 15 and 30 min. Participants were given a USD 50 electronic gift card as an incentive for participating in the interview and Photovoice data collection (i.e., the qualitative phase of the larger aforementioned sequential explanatory mixed methods study). The audio recording of the interview was uploaded to Otter.ai software Version 2022 for transcription.

3.4. Analysis

Thematic analysis (TA) [

25] was used to analyze the data from the semi-structured interviews and participant-produced captions. The six phases include (1) familiarization with the data; (2) generating initial codes; (3) generating themes; (4) reviewing potential themes; (5) defining and naming themes; and (6) producing the report. The first author listened to the recordings and edited transcripts for accuracy. Once the transcripts were ready for analysis, the first author created a single Word document that contained each participant’s interview transcript and participant-produced photographs and captions.

3.5. Trustworthiness

To enhance trustworthiness, the first author engaged in an iterative reflexive process that included identifying assumptions brought to the research process through reflexive journaling [

26]. This process provided a way to record an account of the first author’s internal and external dialogue throughout the research process [

27]. Reflexive journaling was utilized during data collection, analysis, and report writing. Immediately after each interview, the first author critically reflected on both personal (e.g., assumptions, emotional connection to participants, prior knowledge, and sociopolitical events) and functional contexts (e.g., physical environment, logistics, and technological issues) that may have influenced the research process.

Drawing from Consensual Qualitative Research strategies [

28], trustworthiness was also cultivated through peer review, which was undertaken by the second and third authors to minimize bias or preconceived notions when analyzing and developing the themes. Interpretative discrepancies were discussed until a consensus was reached.

4. Researchers’ Positionality Statements

Research in the social sciences is rarely value-free [

29]. As recommended by Roberts and colleagues [

30], the authors acknowledge and locate their social positions in relation to concepts explored in this study, including but not limited to racial and ethnic identity, culture, gender, immigrant generational status, health, and socioeconomic status. The authors’ aim is to consider “where they are coming from” as researchers, including their values, beliefs, and social identities, and how these all converge to influence the research process [

31].

Lalaine Sevillano, the first author is a currently abled cisgender female Pilipinx immigrant and settler. She/they/siya now holds advanced degrees, but grew up holding low socioeconomic status and is a first generation college student. Like many of the AsA students in this study, she also struggled with navigating her/their AsA identity. The second author, Joanna La Torre is a mixed race, second generation, Pilipinx settler, gender/queer Indigenist, decolonial, feminist scholar from middle socioeconomic background. They are a first generation graduate school student who had challenges navigating AsA identity throughout their life. The third author, Taylor Geyton, is a Black American, cis-gender, bi-sexual, woman, from a lower-middle socioeconomic background who was raised in a protestant Christian faith and has since begun to practice Traditional African Religions. She is an activist-scholar-educator and a Licensed Clinical Social Worker.

5. Findings

5.1. Participants

The sample is composed of 14 AsA college students. Seven participants identified as female, and seven identified as male. The mean age of the sample was 19.77 years old (SD = 1.12), and their average perceived socioeconomic status (SES) level was 6.36 (SD = 1.45). For further details on participants’ characteristics, please see

Table 1.

5.2. Photovoice Data

The 14 participants submitted 21 photographs and captions responding to the prompt for images that represented mental and physical health. Participants were given the opportunity to discuss at least three of the photographs submitted in response to the four prompts. Twelve out of the fourteen participants elected to speak about the photo(s) they submitted for the prompt on mental and physical health. As such, the analytical sample also includes 12 transcript excerpts during which participants discussed submitted photo(s).

Four themes developed from the data, including: (Theme 1) mind–body health connection meaning that mental health is about the synchronization of one’s mind and body; (Theme 2) environmental connectedness and the view that mental health is connected to nature; (Theme 3) social connectedness and how interpersonal relationships influenced mental health; and (Theme 4) internalization of the “good Asian student” stereotype and its impact on mental health. These themes are illustrated by the respondents’ photos, captions, and oral discussions of the photographs.

6. Theme: Mind–Body Health Connection

Participants described how mental health was linked to their physical health. They depicted and described experiences when psychological distress manifested as somatic symptoms, when physical health exacerbated mental health challenges and vice versa, and how physical activity and health behaviors impacted mental health.

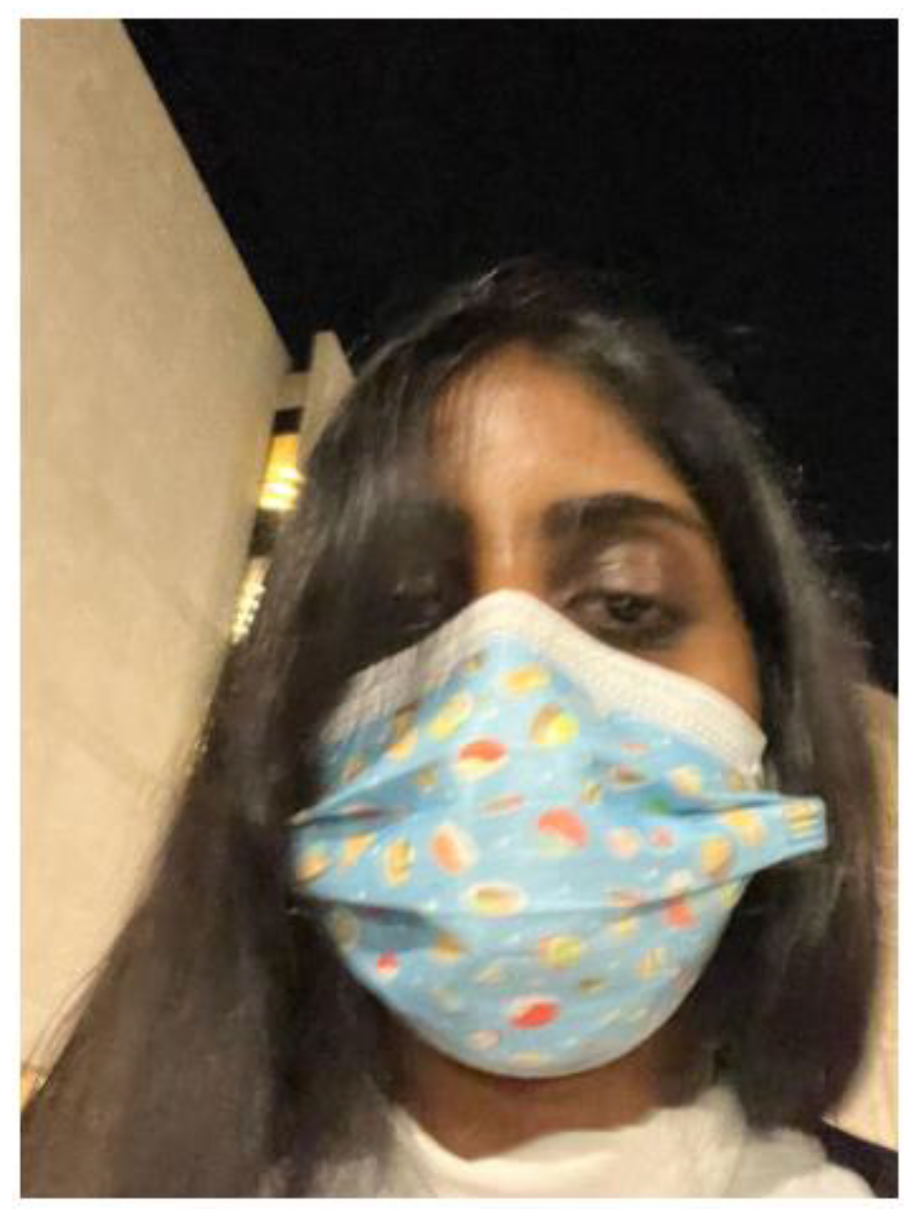

Figure 1 shows Roman capturing his experience with stress-induced hives: “I didn’t know I could have an allergic reaction to being stressed out. That really brought up the notion of how physical and mental health are interconnected with each other. Because your body knows when you’re stressed out”. Similarly, Jellybean shared a photograph of herself (

Figure 2) in which she described the toll that her multiple mental and physical health conditions had on her appearance and energy: “I think my eyes are showing me, I’m very tired. At this point, I was struggling with [Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder] and anxiety. And then also, as I mentioned, I had a really hard time with my leg issue”.

In the examples provided by Roman and Jellybean, the discomfort experienced in their bodies is integral to their mental states and indicative of their mental health. Further, Jellybean’s self-portrait is out of focus, conveying even more the sense of struggle she is enduring at the time the photo was taken. Jellybean’s account of her experience at that time represents her difficulty differentiating between the multiple challenges she faced. In both examples, the body betrayed the mental health of the participant because, as Roman astutely points out, “the body knows”.

Other participants described how mental health was associated with health behaviors.

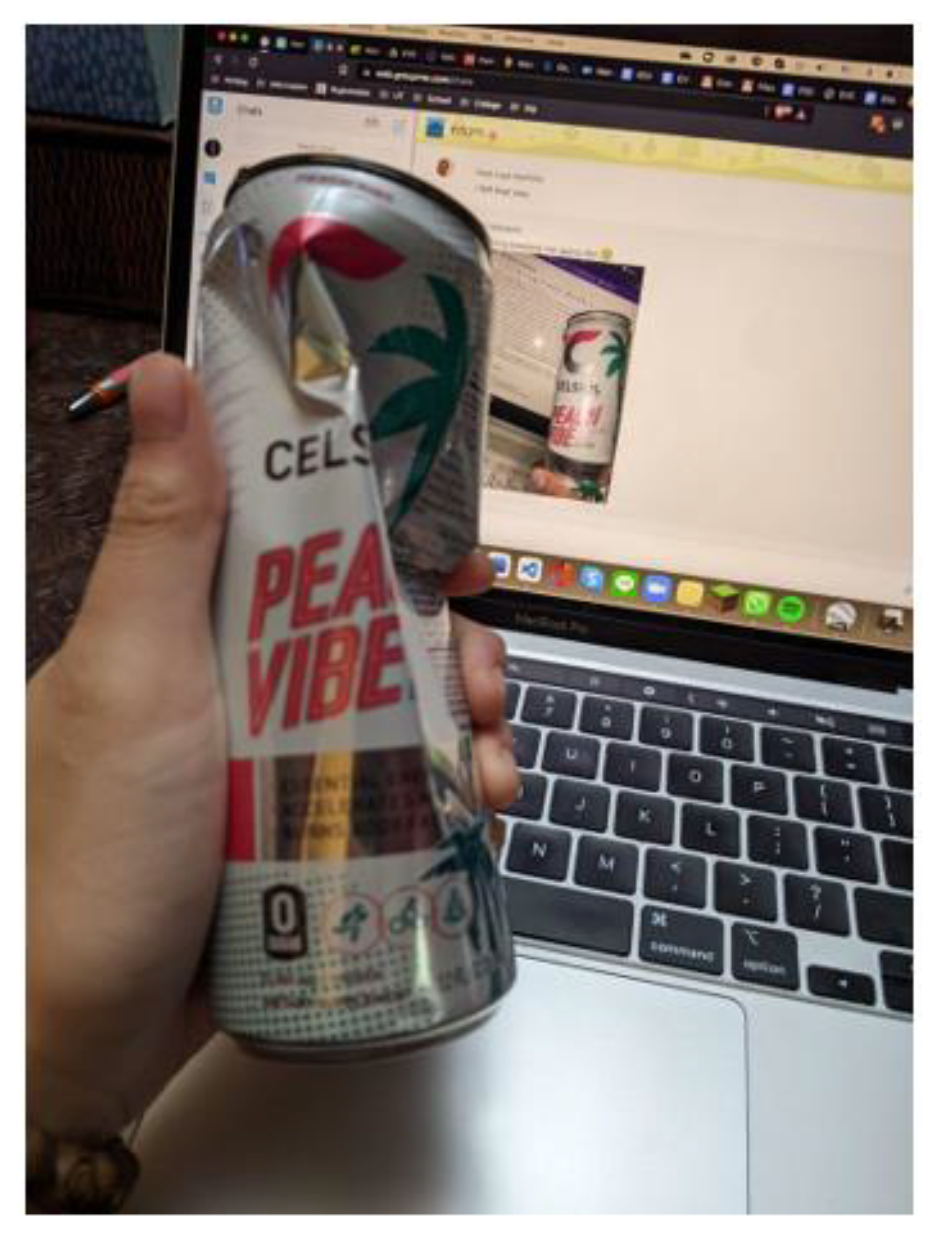

Figure 3 shows Grand holding an emptied and crumpled can of an energy drink. Grand said:

And I crushed up Celsius (brand of energy drink) to represent my mental state at the moment. It’s not doing good, and how even with the added help of caffeine to help push through this final stand, it took a large toll on my mentality. And also with just my physical being as well. Eating habits were terrible during this time. I don’t think I ate for a couple of days, or at least not consistently.

As Grand described, she views the caffeine from the energy drink as necessary for her performance, especially her ability to push through; however, she simultaneously recognizes its negative mental health impact. Participants also shared that health behaviors, such as engaging in physical activity, helped with positive mental health. For example, Spencer said “I love to exercise and move my body”, and Redacted said walking helps him to de-stress.

7. Theme: Environmental Connectedness

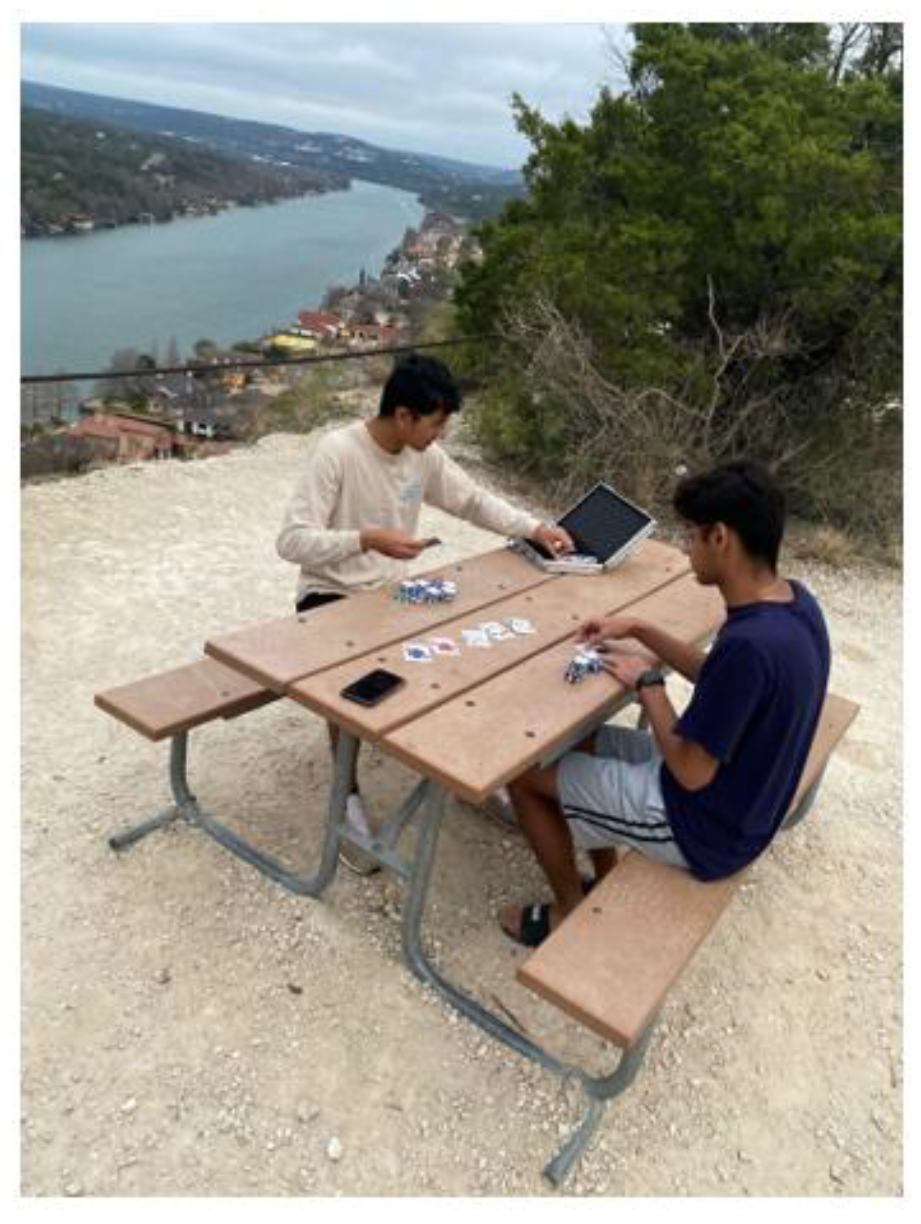

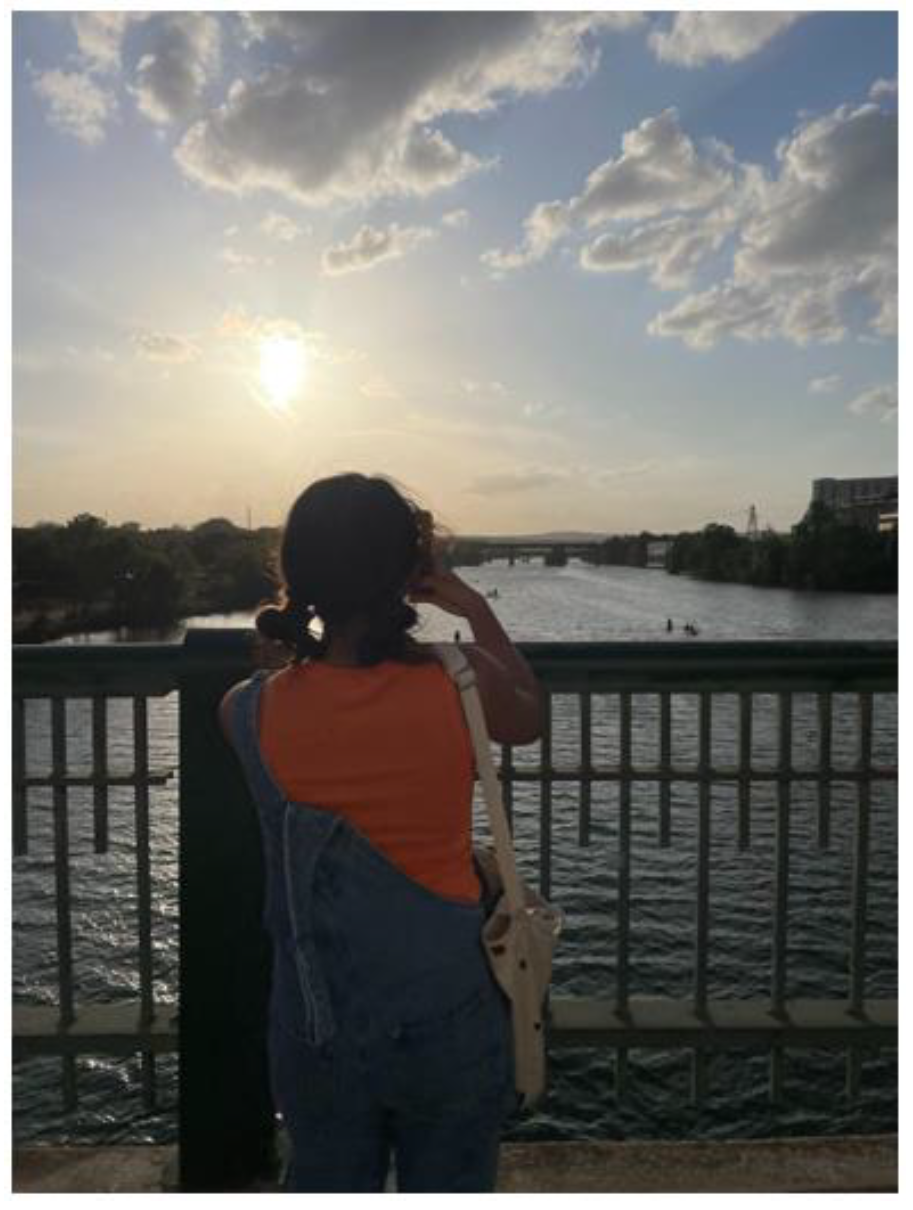

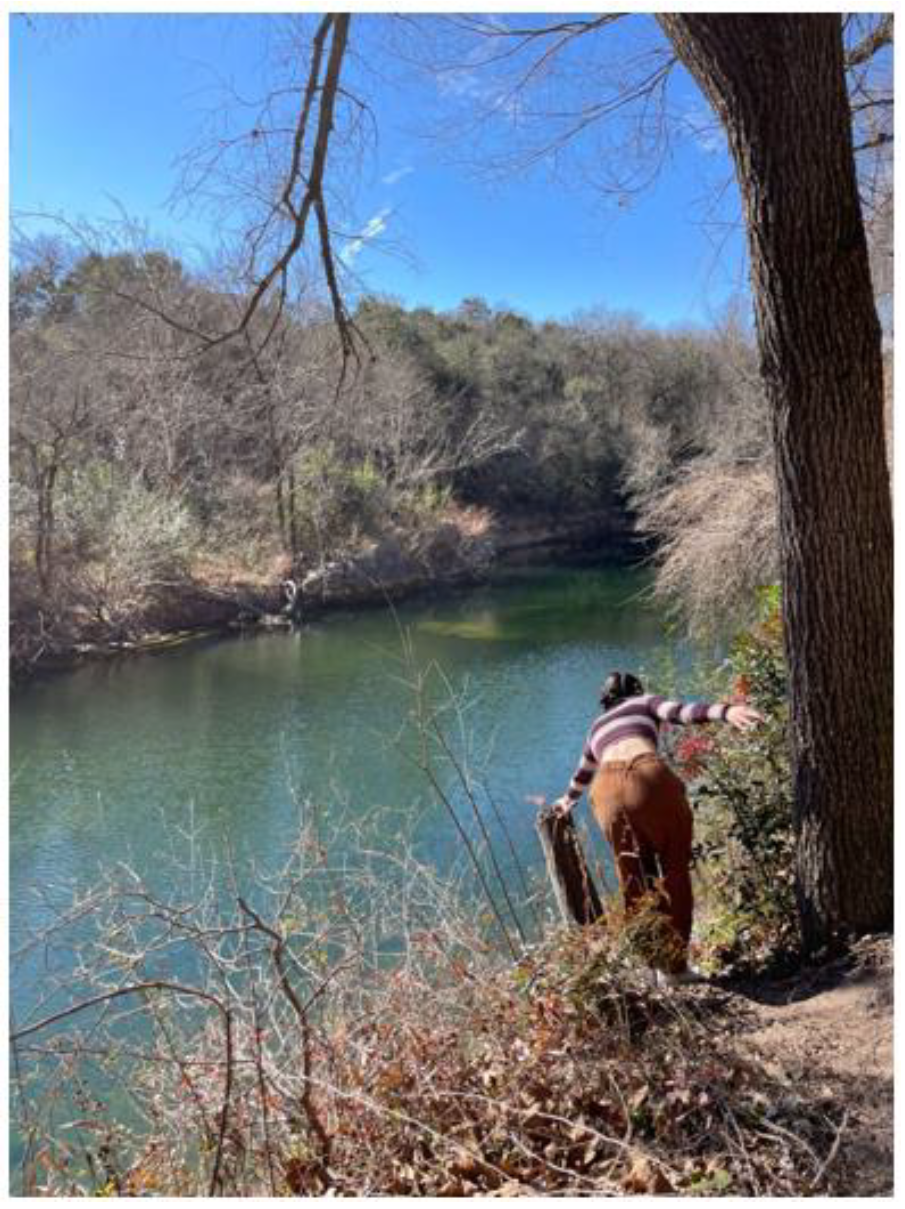

Participants described the connection between their mental health and with the environment, particularly highlighting the influence of being outside in nature. For example, Blue’s photograph (

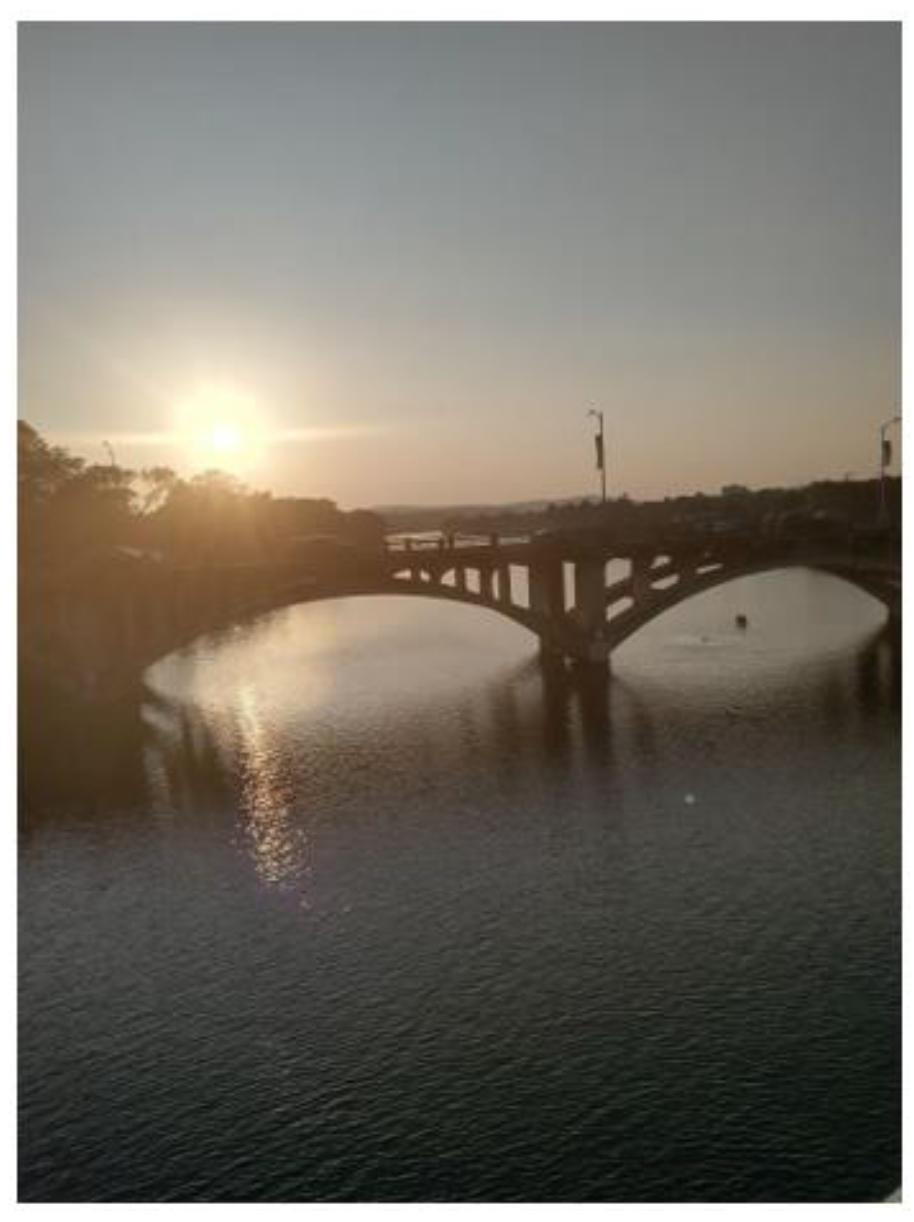

Figure 4) emphasized the “serenity of the environment” as he played poker at the top of Mount Bonnell. Redacted also shared a photograph (

Figure 5) of a scene he took while on a walk and described how “being outside helps [de-stress] from studying”. Spencer chose to share two photographs depicting the relationship between environmental connectedness and her mental health. In

Figure 6, she describes going on walks with peers in nature, and in

Figure 7, she is seen taking a picture of the sunset at Lady Bird Lake and she remembers it as “a very happy moment for me. And I think my mental health was great at the time”. Spencer also shows how she relies on nature for health when describing that she will view photographs taken in nature when she needs a “pick-me-up”. Spencer’s admission exemplifies both her connection to nature and her insight into what helps her during difficult times, demonstrating her resiliency as well.

Spencer, Blue, and Redacted share important insights about how connecting with nature helps enhance their mental health. This comes in the form of relaxation, connecting with beauty, moving their bodies, and a space to connect with friends.

8. Theme: Social Connectedness

Participants highlighted the importance of social connectedness and how it contributes to their sense of belonging, loneliness, and anxiety. This theme was divided into four sub-themes of family, peers, university, and COVID-19 to further contextualize how connections with people mattered to and, in some cases, complicated their mental health.

8.1. Sub-Theme: Family

One participant shared a photo of her family to describe her mental health. In

Figure 8, Eli states that although her family is a source of support, “mental health is a difficult subject, […] they don’t quite understand my relationship with it”. Eli’s example provides a rich illustration of the known gap between Asians in the diaspora, the next generation, and applied western mental health concepts. Eli feels compelled to remain close to her family and even experiences them as supportive of her mental health, yet she still lives with a sense of illegibility when it comes to her mental health.

The support Eli receives from her family is notably embedded within culture, both as a praxis and a site of reproduction. That is, the family depicted sits down to enjoy culturally specific foods endowed with meaning and practice and, in so doing, reproduces culturally laden praxes, including ways of connecting with family, ways of receiving support, and practices of membership and identity. In this way, Eli’s example demonstrates integral sustenance practices that span physical, social, and cultural spaces, all while enduring a misalignment regarding mental health in the diasporic context.

Although other participants did not share photos of their families, several spoke about how ruptures in family connectedness contribute to poorer mental health. Lana shared that she chose a photograph of her smiling (

Figure 9) to describe her struggles with body image, in part related to white supremacist beauty standards transmitted to and from her family and her related insecurities: “Whenever I take pictures in general, I always feel conscious of my appearance in a way. My relatives have always been, ‘Oh, you’re fat’ and stuff like that. And so I would get really self-conscious about my appearance”. Lana’s example demonstrates the insidious intergenerational effects of racialization and how these contribute to shame, negative self-perception, and strained relationships, as well as mental health outcomes.

Lana’s resilience is also captured in the moment photographed and her telling of it, as she identifies and externalizes her knowledge that the beauty standards she and her family were/are subjected to are “unrealistic”. In this way, Lana demonstrates a growing critical consciousness that uproots the white supremacist beauty ideals she has been subjected to and potentially widens the path for centering herself in the knowledge of her beauty. Regardless, the photo captures one moment of victory and joy over the harmful messages she received throughout her lifetime. Roman also alluded to tensions with his family and how those conflicts potentially contributed to the aforementioned stress-induced hives: “They kept holding on to this childhood version of me and it was causing a lot of tension and friction. […] It definitely is a journey on its own when explaining to your parents that you’re not the same child, you’re not a baby anymore”. Roman describes developmentally appropriate issues of differentiation and how his body reacted to this process. In these examples, family is intertwined with cultural, historical, and socioeconomic forces (e.g., immigration) that produce both risks and benefits due to the broader systemic forces at play (e.g., racism). Asian families moving to the U.S. undergo enculturation and acculturation processes known to catalyze generational differences in epistemology, lived experience, health, and mental health. As such, family connectedness represents an integral theme for AsA college students as a liminal space of emergence as young adults and re-emergence as cultural (dis-)continuity within a fresh context.

8.2. Sub-Theme: Peers

Many of the participants described that their friends provided positive mental health support by offering a space to talk, engaging in shared interests, and receiving validation and recognition from their community. As in

Figure 7, where Spencer described simultaneously connecting with nature and friends, talking with peers is seen as integral for mental health. Pastel Pink shared a photograph of herself and her friends from the acapella group that she is a part of (

Figure 10) and says “Mental health is a big part of this picture as well, because it’s just been so great being a part of this group”. Pastel Pink describes the benefits of a sense of belonging enjoyed through completing shared interests together. The photo and caption, “Sing your Heart Out”, convey joy, playfulness, and positive expression.

Other participants described social activities with friends, such as sharing a meal (Redacted) and playing poker (Blue), which help them decompress. Similarly, in

Figure 7, Spencer shared a photograph of her friend and described that time spent with friends, including speaking about current challenges “is so comforting and encourages me to keep going”. In this way, the connection experienced represents potential protective factors for the sample.

Another dimension of feeling connected to peers is the ability to help them in times of need. Pastel Pink shared a photo captioned “Party time” (

Figure 11). She stated she is not “a huge party person” but that her experiences with parties allow her to help others who may find themselves in compromising situations: “So, I think that impacts my mental health like positively when I know that these people not only are willing to call me and ask me for help, but also I know what to do and what to tell them”. Pastel Pink described elements of being part of a community, both of which give her esteem and recognition as a member of a group, and doing what Pastel Pink views as esteemed actions (i.e., providing care that is both valued and needed within her community).

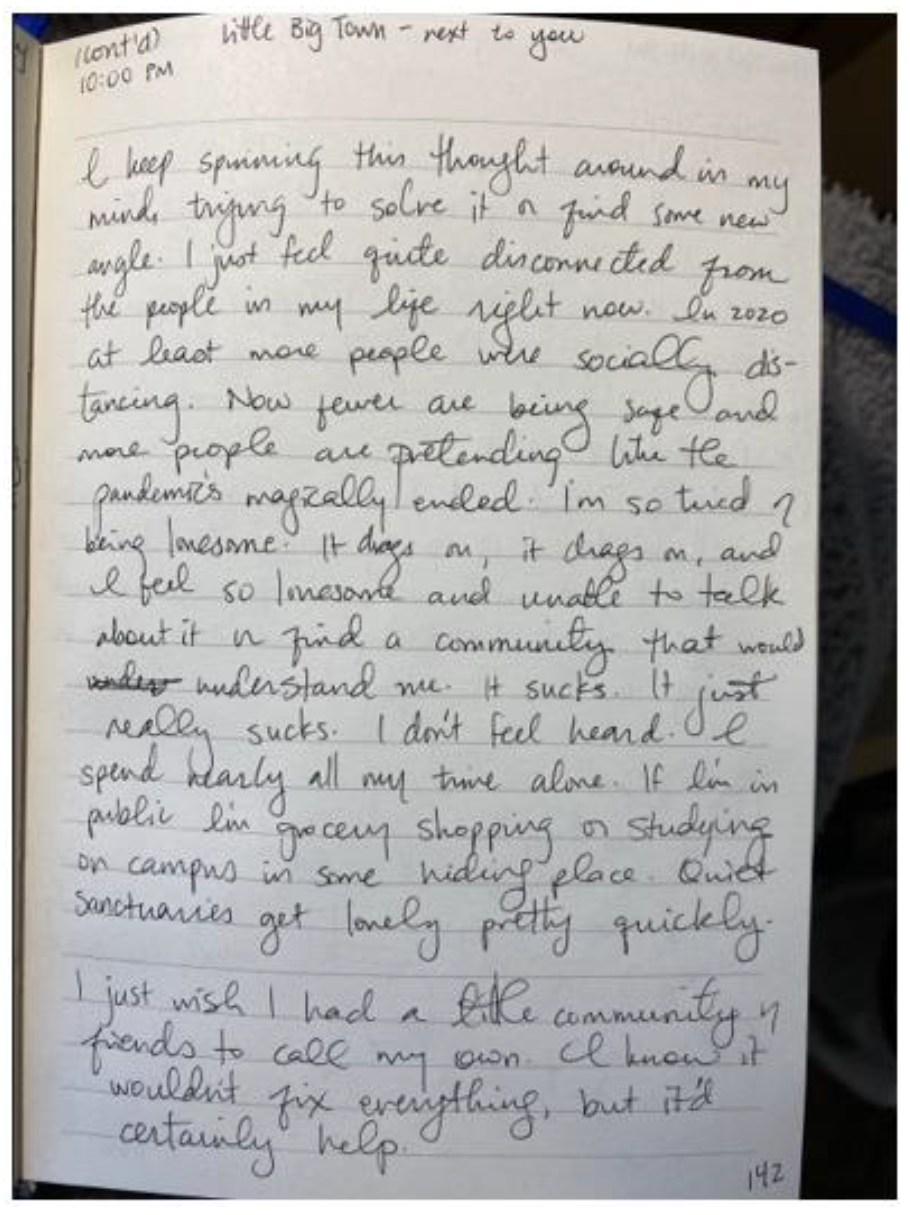

8.3. Sub-Theme: Impact of COVID-19

Many participants described how the COVID-19 pandemic and associated policies (e.g., stay-at-home orders) affected their mental health by obstructing their social connectedness, adding pressure to their family relationships and home environments, and limiting their ability to build and maintain social networks. Roman, for example, described added “tension and friction” with his family, and both Roman and Hazel discussed navigating isolation related to the pandemic. Additional consequences of the COVID-19 disruption to connectedness include the ambivalence and anxiety produced in re-learning how to socialize within a highly uncertain time composed of rapidly shifting and sometimes contradictory policies, incongruence between governmental agencies, and continued widespread disease. Hazel took a photo of one of her diary entries (

Figure 12) describing this cycle of feeling lonely yet feeling anxious about the possibility of contracting COVID-19. She provided the following description to accompany her photo:

Well, it is 10 o’clock, and I’m listening to a sad song. So, there’s that scene. And so this was essentially when I was [staying] up a little bit late and writing about the fact that I wished I could meet more people. But, I didn’t really know how, and also because of COVID restrictions, it’s also hard. It’s a little bit of a gamble to meet new people. Because well, I don’t really know where you are. I don’t know if you’re sick, you probably don’t have COVID, but if you do, I would have to go get tested. […] You can feel sort of lonely, and it’s hard to talk to other people about. First of all, it’s a bit embarrassing to talk about. And also, if you’re lonely, you don’t have that many people to talk to.

Hazel’s description and photo provide a palpable sense of the difficulties she experienced navigating the various hardships associated with the pandemic. She describes the competing pressures and needs of loneliness, pandemic safety protocols, social pressures, and loss of her anticipated college classroom experiences, all while navigating the mental health impacts of each of these separately and individually. The pain, fear, anxiety, and sadness mix together, along with developmental processes of emancipation and differentiation in this theme.

9. Theme: Internalization of the “Good Asian Student” Stereotype

The fourth theme that developed was the experience of maintaining race-based stereotypes and how the internalization of the said stereotypes affected their mental health. The most prominent stereotype participants seemed to internalize was that of the “good Asian student”. Many participants described the pressure to do well academically because it was expected of them from peers, families, and society. Grand stated that “I was determined to fulfill this image of myself that I wanted of a ‘good Asian student’ and that I needed to struggle in order to get to that ideal image”. They elaborated on this in

Figure 3 where they depicted consuming items that helped them perform at the expense of behaviors that helped them feel balanced, well-rested, and well-nourished. Alphonse shared a photo (

Figure 13) of himself collapsing on his bed after a long day of studying and explained:

And I don’t think this is [AsA] specific, but a lot of other immigrant students, first gen, low income students feel like a big pressure to be very successful and that also playing to the stereotype that by being first gen, I’m trying to assimilate and be successful. But, a lot of people are genuinely, extremely stressed by the workload and stuff. And a bit overwhelmed. At least compared to their peers that they feel the need to feel better to succeed. And a lot of times it is kind of unsustainable that I just collapse on the bed at times.

Despite recognizing a decline in their well-being (mental and physical), participants spoke about the need to “push through the academic pressure”, as Grand and Alphonse explained. For example, Jellybean was bedridden with a pelvic injury, yet she found herself “thinking about academics, […] and stressing about it”. The binary presented of being the “good” AsA student also denotes the presence of the bad AsA student and all the implications therein, including the meanings ascribed to not performing up to the stereotyped level. To avoid this, the students put their physical and mental health on the line, even when, as with Jellybean, they experienced serious consequences pushing through to perform. Distinct from the insight illustrated when contending with racialized messages around beauty standards, the participants did not externalize the pressures to perform by locating them within harmful white supremacist discourses, which suggests that the stereotype remains intact internally. That is, though Grand identified the presence of the “good” Asian (i.e., the model minority stereotype), they did not challenge the stereotype itself or link it with broader contextual factors; thus, he remains subject to the binary outcomes of good/bad.

When asked what advice they would give to other AsA students about mental health, many participants suggested that AsA students should strive for a better sense of work–life balance as Blue recommended:

I feel academics are extremely important. But it’s also important to make sure that you are having fun in life and that you’re getting out there and you’re doing stuff that makes you happy. […] Your time at UT is a very short one—make sure to get the most out of it. You’re not just focusing on school, but you’re also, putting out some time to … make sure that your grades are good, but make sure that you’re also having fun and that you’re in a good place mentally.

Redacted added, “They should socialize […] Being in college is not about studying all the time. You should also take time to look for hobbies or, it’s time to find what you like and don’t like”. Blue and Redacted’s shared sentiments maintain the impetus for a work–life balance to be on the AsA students themselves rather than adjusting external factors. Without a structural basis for shifting the material, pleas for heeding a hypothesized work–life balance function more like a paltry sentiment rather than actual change.

Participants also seemed to internalize the model minority stereotype (MMS) in ways that made them feel as if they should keep their mental health struggles to themselves. Alphonse explained, “I hesitate a lot to describe mental health struggles because I feel like I don’t want to victimize myself that way”. To counter this stigma of seeking help, participants suggested that AsA students should check in with themselves and critically reflect on their mental health because many ignore or are not aware of their maladaptive coping strategies. Indeed, Finn cautioned about how “easy [it is] to fall back on certain habits or substances in times of stress” while describing a sketch of a “pained” man in

Figure 14.

Alphonse expressed, “I don’t really have a good solution for that. But I wish there was more awareness that a lot of students are overworking and employing these bad mental health strategies”. Roman emphasized the need to normalize mental health help-seeking and suggested the following: “I guess investing more in or at least promoting students to take a more active approach to their mental health”. Jellybean shared that taking a mindfulness class could be a potential strategy to promote mental health, particularly around self-compassion. She warned other AsA students:

[…] don’t ignore how you’re really feeling and act like it’s not there. If you just ignore it, there’s just going to be so many unresolved things that you’re gonna have to deal with in the future, and that’s going to give you anxiety. I don’t know, it just all piles up, and it will show on your physical health and your mental health.

In summary, this theme described how the internalization of the “Good Asian Student” stereotype manifests and shapes the bio–psycho–social well-being of AsA students.

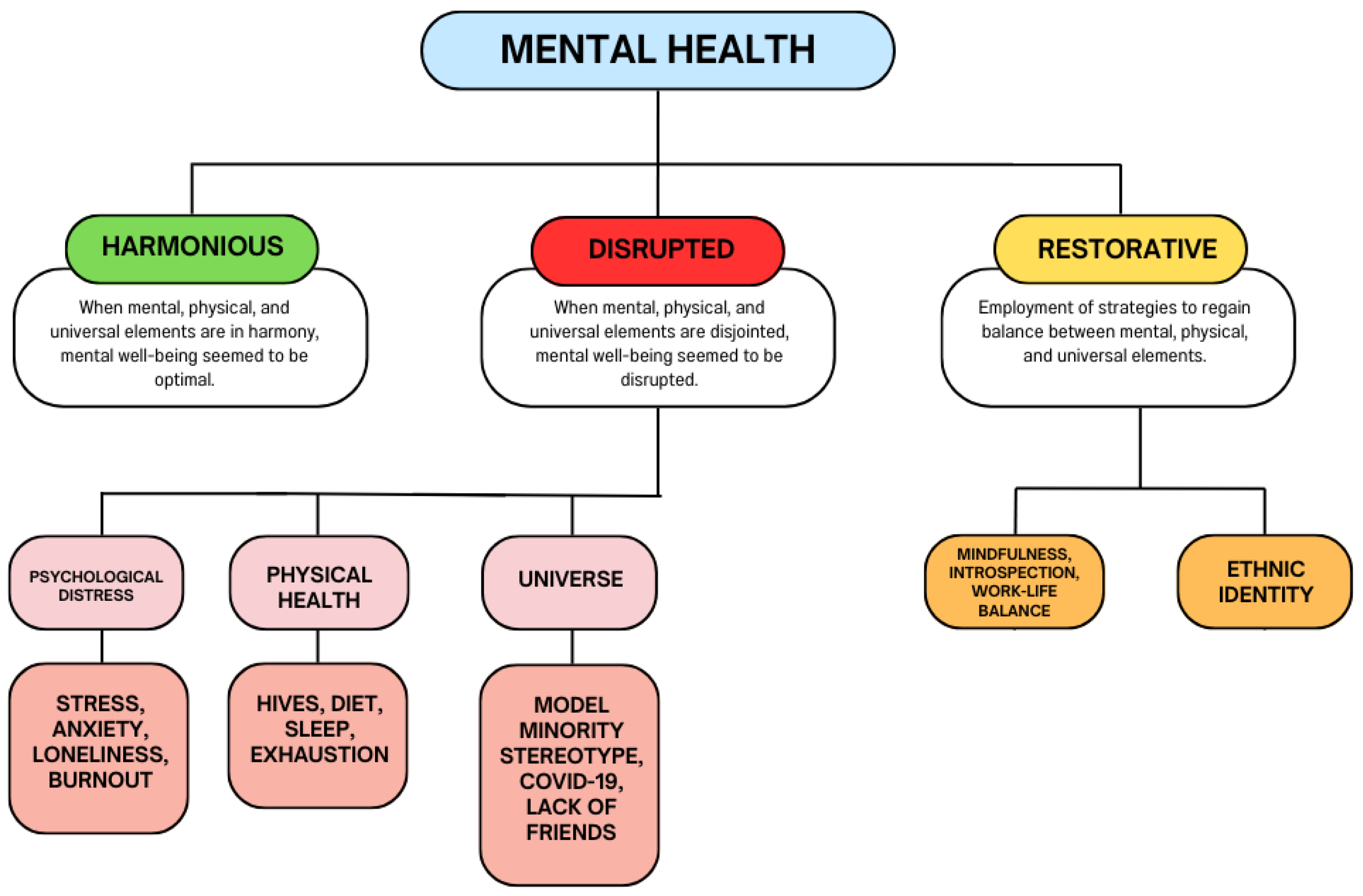

10. Concept Map

Following a similar approach to Byrne [

32], the authors developed a concept map (

Figure 15) to depict how data items relate to their respective themes. The process of developing this concept map revealed how AsA mental health was dependent on the cohesion of mental, physical, and universal (i.e., social and environmental) connectedness. When these elements were in harmony, mental health seemed to be optimal. Conversely, when these elements were disjointed, mental health was disrupted. A third concept of restoration became apparent, wherein AsA emerging adults employed various strategies in attempts to regain balance between mental, physical, and universal connectedness. This concept map will guide the discussion of our findings.

11. Discussion

In this study, we present a novel contribution to the empirical literature by providing the first Photovoice exploration, to our knowledge, of mental health among AsA emerging adults in the southern U.S. during the COVID-19 pandemic. Our findings suggest four themes: (Theme 1) mind–body health connection and the experience that mental health is about the synchronization of one’s mind and body; (Theme 2) environmental connectedness and the view that mental health is connected to nature; (Theme 3) social connectedness and how interpersonal relationships influenced mental health; and (Theme 4) internalization of the “good Asian student” stereotype and its impact on mental health. As aforementioned, our concept map captures how the themes come together to form a higher level understanding of the ways AsA emerging adults conceptualize mental health. Specifically, the concept map indicates that mental health has different states of harmonious, disjointed, or restorative based on the cohesion of mental, physical, and universal connectedness. Definitions of mental health continue to evolve. Our findings are aligned with Galderisi and colleagues’ more holistic definition which is gaining global attention:

Mental health is a dynamic state of internal equilibrium which enables individuals to use their abilities in harmony with universal values of society. Basic cognitive and social skills; ability to recognize, express and modulate one’s own emotions, as well as empathize with others; flexibility and ability to cope with adverse life events and function in social roles; and harmonious relationship between body and mind represent important components of mental health which contribute, to varying degrees, to the state of internal equilibrium [

33].

This definition corresponds to our findings that mental health is an ever-changing condition with active shifts in balancing mental, physical, and social components of well-being. Additionally, this definition of mental health also highlights the idea of harmony which our findings elucidate.

11.1. Harmonious Mental Health

The first state of mental health, harmonious mental health, included participants’ perceptions that mental health cannot exist independently from physical and socio-emotional health. Participants shared photographs and narrated experiences, which demonstrated that mental health was connected to physical conditions, health behaviors, environmental factors, and social support. Our findings are aligned with the robust literature on traditional beliefs among Asian cultures that mental health is viewed as the integration of the mind, body, and universe, unlike westernized health models that dichotomize the mind and body and divide communities into individuals within which mental health resides [

34]. For example, in South Asian culture, Ayurvedic healing is based on the belief that an individual is simultaneously a physical body, a soul, and a social being; thus, if one of these areas is affected, the other areas are as well [

34,

35].

Beyond the self, participants also described mental health in relation to their connection to nature. These findings are also aligned with traditional Asian cultural views of health, including that of some Indigenous Pilipino cultures, which subscribe to holism as the synchronization of one’s mind, emotion, and action and that health is connected to the natural elements of earth, fire, water, and air, with each connected to parts of the body, such as bones, metabolism, blood, and oxygen [

36]. Further, Asian cultures are known to be collectivist in nature; thus, mental wellness builds from well communities. As diasporic communities are variously impacted by structural forces and adapting to new environments, this also impacts wellness within the community and mental health.

Participants also described that their mental health was associated with social harmony. This connection with others also aligns with traditional Asian health views in that health is associated with one’s “sense of orientation toward others (as compared with the western orientation toward the individual self)”, [

37]. Pastel Pink especially exemplifies this belief when she describes the pride she feels after being able to help friends who reach out in times of need because these incidents show the trust and deep connection she has with them.

11.2. Disrupted Mental Health

Conversely, the second state of mental health describes what happens when the harmony between mind, body, and universe is disrupted. Roman described mental health by sharing a photograph and experience about how an imbalance in stress (mind) led to somatic symptoms of hives (body). Similarly, Jellybean described mental health by explaining how her pelvic injury (body) exacerbated feelings of anxiety (mind). On the other hand, Spencer described that she enjoys (mind) physical activity (body) in nature (universe). Again, these findings are aligned with traditional Asian cultural views of health, particularly that of holism [

37]. These findings affirm previous research, which suggests that AsAs view mental and physical illnesses as imbalances of various forces or energies (e.g., yin and yang in Chinese culture); harmony is essential for longevity and wellness [

37].

This harmony within the self seemed to be disrupted, in part, by the internalization of race-based stereotypes, such as the model minority stereotype (MMS). This racialized stereotype falsely aggrandizes AsAs as the exemplary racial minority group because of their purported educational and financial success while simultaneously exerting downward pressure on those racialized as Black, Latine, and Native American, for example [

38]. Grand said it best (as evidenced by the title of our manuscript) that they felt immense pressure to uphold the “good Asian student” stereotype. The stress from wanting to maintain that image and associated social status or position, led to ignoring basic needs such as eating and rest. Alphonse also shared that because he needed to do well in school, he would study for many hours to the point of physical exhaustion, “collapsing” on his bed even with his backpack still on his body. In addition the harms caused to groups thrust downward by the act of stratifying racialized groups, these respondents spoke to their uptake of the stereotype, in pursuit of perceived benefits, and the resulting consequences to their embodiment. While the MMS, on the surface, presents as innocuous for AsAs who apparently benefit from it, this sample gives voice to insidious effects on mental health.

Although participants did not explicitly state that the COVID-19 pandemic impacted their harmony with nature, Roman and Jellybean mentioned that the pandemic forced them to stay at home. Emerging research shows that during the pandemic, mental health, connection to nature, nature-based experiences, and outdoor play declined for adolescents in the U.S. [

39]. As such, we assume that the pandemic may have caused fluctuations in participants’ connectedness to nature, thus negatively impacting their mental health.

Disruption to social harmony also seemed to shape participants’ mental health. Hazel, in particular, described how her unmet need to meet and connect with others led to loneliness and burnout. This is important because research on AsA college students shows that they tend to turn to social connections and peers for mental health support and help-seeking [

6]. Further, social connectedness has been shown to be a protective factor against depression [

40].

Along with the disruption of social connectedness with peers, disruption with family connectedness also contributed to poorer mental health. Tensions about mental health within the familial context could be due to collectivist traditions that uphold social and family harmony over individual displays of emotions. For example, the value of saving face and maintaining a family’s public image is very important. As such, mental health is stigmatized in many Asian cultures because mental health concerns could be seen not only as an individual weakness but as one shared by the entire family [

41]. Yet, recently published results from a longitudinal study with AsA adolescents indicated that family connectedness in adolescence predicts lower odds of adverse mental health outcomes such as depression, anxiety, and suicidality [

2]. This study, along with the present study’s findings, suggest that bolstering family connectedness, particularly around destigmatizing mental health, may improve the mental health of AsA emerging adults.

In summary, AsA emerging adults believe that optimal mental health is maintained through harmonious connections with the self (mind–body) and the universe (nature, peers, family).

11.3. Restorative Mental Health

The third state of mental health captures the lessons learned and the advice participants offered to other AsA emerging adults about how to restore their mental health. First, participants suggested practicing mindfulness as a way to critically reflect on one’s emotions, needs, and challenges. Jellybean described a key takeaway from her educational psychology course entitled “Mindfulness: The Self and Compassion” was to not ignore concerns as they will breed even more unresolved issues. Instead, she learned to acknowledge problems as they arise and ask herself questions like “How am I feeling about this? Is there anything I can do to fix how I’m feeling? What are the steps that I can take to make my situation feel a little bit better?” She argued that if she had learned these tools earlier, her “mental health would have been in a better situation [… I would have] overcome my anxiety instead of stressing about everything”.

Roman also alluded to a similar strategy: to “reflect on how you’re feeling” as a way to promote a more proactive approach to investing in one’s mental health. Grand suggested that the university could support AsA students’ mental health by making resources more available, such as providing low-cost remote counseling sessions. Another component of mindfulness, according to respondents, is the development of work–life balance, particularly in response to the pressures of academic expectations. Blue and Redacted both advised AsA students to have fun, socialize, and find things that they enjoy. This idea of looking inward is aligned with Asian cultural introverted inclinations as opposed to western culture’s extroverted inclinations. Specifically, the idea is that health is about “self-control, self-discipline, self-cultivation and self-transcendence” rather than demanding others to change and/or trying to alter external social factors [

42].

Many participants described experiences of internalizing the MMS, but they did not explicitly provide recommendations on how to combat it, in part because they also did not differentiate from it. That is, though there was recognition of the stereotype itself, it was not put in its place as part of a broader external structural force they are subject to. Prior research shows that AsAs tend to cope with racism through forbearance coping, or enduring or tolerating a stressor [

43]. Forbearance coping, or the tendency to de-emphasize hardship for the sake of the group, has been recognized as a culturally congruent strategy typically found in collectivist cultures [

44]. The authors also draw upon previous research to emphasize the importance of developing a positive orientation towards one’s ethnic group (i.e., ethnic identity) in deterring internalization of race-based stereotypes among AsA emerging adults [

45,

46]. Ethnic identity is a multi-faceted construct that refers to one’s sense of belonging to a group that shares a culture, including traditions, foods, values, and language [

47]. Indeed, AsA college students who endorse more positive beliefs about their racial/ethnic group also report higher well-being scores despite an increase in race-related stress [

48]. Thus, supporting AsA emerging adults in uprooting the stereotype and/or fostering ethnic identity should be explored as buffers for mental health outcomes. Further, an increased understanding of the origins and function of the MMS, for example, its role in breaking apart racial alliances, could expand response options and help disrupt the “good/(bad) Asian student” binary endured [

49].

Overall, findings from our study support the prior research, including the seminal report published by the Lancet that culture and health are inextricably linked [

50]. Synthesizing the robust literature on culture and health, Kagawa-Singer [

51] states that culture is a mechanism for survival to navigate cognitive and emotional processes, facilitate meaning-making, and develop interpersonal and institutional supports. The findings of our study corroborate this theory and demonstrate that culture impacts the expression and recognition of mental health among AsA emerging adults. Additionally, culture plays a role in the ways AsA youth cope with mental distress.

12. Implications

12.1. Challenges and Future Opportunities

This research has several strengths, including its novel approach of using Photovoice methodology, data collection during a pivotal time in history, and amplification of the often invisibilized lived experiences of AsAs. However, several challenges and future opportunities should be named. First, the Photovoice methodology allowed AsA emerging adults to record and reflect on their strengths and challenges. Emerging research has shown that Photovoice can also be used as an intervention with college students to improve their mental health and well-being [

52,

53]. Future studies should explore if such interventions would be effective with students who identify as AsA.

Continued exploration is also warranted because this study is cross-sectional, which limits our understanding of how AsA emerging adults view mental health to a single time point. This may be confounded by developmental stages, including that of ethnic–racial identity development, which has recently been described as an ongoing process that spans the life course [

54]. Future studies should explore the possibility that views on health change throughout the life course, particularly for minoritized racial/ethnic people. Moreover, data collection occurred during a significant historical period when AsAs faced dual pandemics, COVID-19 and the rise of anti-Asian discrimination and hate. Both have been posited to influence AsA mental health [

7,

40]. Future studies should continue to explore the impacts of these historical events on the holistic well-being of AsAs.

Another strength of the study is centering the voices of AsAs, who continue to be underrepresented in health and social science research [

8,

9]. However, AsAs are not a monolith, and when treated as such, critical differences are missed. Future studies should continue to draw on critical race theory [

55], especially the tenet on intersectionality, to further excavate the lived experiences of AsA youth who also identify as LGBTQIA+ and/or gender expansive. Some of our participants mentioned that they have not disclosed their sexual orientation and/or gender identity. Recent reports indicate that 40% of queer AsA youth seriously considered suicide in the past year [

56]. As such, future studies should aim to look at how intersecting sources of oppression are impacting AsA youth.

12.2. Practical Recommendations

Findings from this study support and emphasize prior research that indicates that the integration of culturally specific values, norms, and expectations with evidence-based practices in mental health is critical to effectively address the mental health concerns of AsA youth [

57]. Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT), an integration of cognitive restructuring, behavioral therapies, and mindfulness activities, has been established as an effective treatment for AsA youth diagnosed with myriad mental and behavioral health disorders [

58,

59]. Additionally, CBT and AsA values intersect at points that increase the success of this modality in reducing symptoms and aiding recovery [

60]. Cognitive and behavioral aspects of CBT are directly relevant to the theme of mind–body connection. For example, CBT modalities emphasize cognitions as the source of circumstantial distress and the restructuring of these cognitions (cognitive restructuring) as the way to change the experience of the circumstance. Additionally, behavioral activation asserts that cognitions about the circumstance can be driven by behavior; thus, taking a walk or exercising can aid the restructuring of cognitions and, ultimately, the experience of distressing circumstances. Moreover, connection to nature and mindfulness have been indicated as promoters of positive well-being and mediators for perceived stress among college-age youth [

61].

The involvement of family members is recommended in CBT among youth. AsAs value family integration and often maintain family definitions that include chosen and extended family members [

60]. The inclusion of family members through educating them about what is being taught in sessions and for the purpose of improving family connectedness has been effective for increasing engagement among AsA youth [

62]. Moreover, group-based interventions with AsAs are more successful than individually based interventions [

57], affirming the importance of social connectedness in the mental health experiences of AsA youth. Finally, CBT’s highly directive treatment approach, where therapists assign “homework” to be completed between sessions, may align well with AsA values of respecting authority, hierarchical social relationships, and interpersonal harmony [

57].

13. Conclusions

Health equity is about demanding the attention and resources to address the different needs of minoritized populations. Despite being the fastest-growing racial group in the U.S. [

63], the AsA population remains the least studied. In fact, between 1992 and 2018, the National Institutes of Health (NIH) funded only 529 studies centered on AsAs, composing only 0.17% of the NIH’s budget during that time period [

8]. The paucity of data about AsAs routinely minimizes the health disparities they face and bolsters the model minority stereotype. The findings from our study aim to inform the development of culturally embedded prevention and intervention strategies to promote health equity for AsAs.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, L.S.; Methodology, L.S.; Validation, L.S., J.C.L.T. and T.A.G.; Formal analysis, L.S.; Investigation, L.S.; Resources, L.S.; Data curation, L.S.; Writing—original draft, L.S., J.C.L.T. and T.A.G.; Writing—review and editing, L.S. and J.C.L.T.; Supervision, L.S.; Project administration, L.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Institutional Review Board of the University of Texas at Austin (STUDY00002058 and approved on 22 November 2021).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets presented in this article are not readily available to protect participants per our approved Institutional Review Board protocol. Requests to access the datasets should be directed to Lalaine Sevillano at

L.Sevillano@pdx.edu.

Acknowledgments

Thanks to the students who shared their stories with us both through words and pictures. We also appreciate seed funding from the University of Texas at Austin’s Office of the Vice Provost for Diversity to be able to provide incentives to students who participated.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funding sponsors had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript, nor in the decision to publish the results.

References

- U.S. Pew Research Center. 2021. Available online: https://www.pewresearch.org/short-reads/2021/04/09/asian-americans-are-the-fastest-growing-racial-or-ethnic-group-in-the-u-s/ (accessed on 2 February 2024).

- Iyer, P.; Parmar, D.; Ganson, K.T.; Tabler, J.; Soleimanpour, S.; Nagata, J.M. Investigating Asian American Adolescents’ Resiliency Factors and Young Adult Mental Health Outcomes at 14-year Follow-up: A Nationally Representative Prospective Cohort Study. J. Immigr. Minor. Health 2022, 25, 75–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- US Census Bureau. Census Bureau Data. 2020. Available online: https://data.census.gov/ (accessed on 6 March 2024).

- Office of Minority Health. Mental and Behavioral Health—Asian Americans. US Department of Health and Human Services. 2021. Available online: https://minorityhealth.hhs.gov/mental-and-behavioral-health-asian-americans (accessed on 2 February 2024).

- WHO. Mental Health. World Health Organization. 2022. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/mental-health-strengthening-our-response (accessed on 2 February 2024).

- Dong, H.; Dai, J.; Lipson, S.K.; Curry, L. Help-seeking for mental health services in Asian American college students: An exploratory qualitative study. J. Am. Coll. Health 2020, 70, 2303–2310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huynh, J.; Chien, J.; Nguyen, A.T.; Honda, D.; Cho, E.E.; Ngo, T.D. The mental health of Asian American adolescents and young adults amid the rise of anti-Asian racism. Front. Public Health 2023, 10, 958517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ðoàn, L.N.; Takata, Y.; Sakuma, K.L.K.; Irvin, V.L. Trends in Clinical Research Including Asian American, Native Hawaiian, and Pacific Islander Participants Funded by the US National Institutes of Health, 1992 to 2018. JAMA Netw. Open 2019, 2, e197432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Museus, S.D.; Kiang, P.N. Deconstructing the model minority myth and how it contributes to the invisible minority reality in higher education research. New Dir. Institutional Res. 2009, 142, 5–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- SAMHSA. National Survey on Drug Use and Health: 2-Year RDAS (2019 to 2020). Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. 2020. Available online: https://datatools-samhsa-gov.proxy.lib.pdx.edu/#/ (accessed on 2 February 2024).

- Lipson, S.K.; Zhou, S.; Abelson, S.; Heinze, J.; Jirsa, M.; Morigney, J.; Patterson, A.; Singh, M.; Eisenberg, D. Trends in college student mental health and help-seeking by race/ethnicity: Findings from the national healthy minds study, 2013–2021. J. Affect. Disord. 2022, 306, 138–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, Y.; Park, M.; Noh, S.; Lee, J.P.; Takeuchi, D. Asian American mental health: Longitudinal trend and explanatory factors among young Filipino- and Korean Americans. SSM—Popul. Health 2020, 10, 100542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.E.; Zane, N. Help-seeking intentions among Asian American and White American students in psychological distress: Application of the health belief model. Cult. Divers. Ethn. Minor. Psychol. 2016, 22, 311–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lipson, S.K.; Kern, A.; Eisenberg, D.; Breland-Noble, A.M. Mental Health Disparities Among College Students of Color. J. Adolesc. Health 2018, 63, 348–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kam, B.; Mendoza, H.; Masuda, A. Mental health help-seeking experience and attitudes in Latina/o American, Asian American, Black American, and White American college students. Int. J. Adv. Couns. 2019, 41, 492–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, H.-L.; Kwan, K.-L.K.; Sevig, T. Racial and ethnic minority college students’ stigma associated with seeking psychological help: Examining psychocultural correlates. J. Couns. Psychol. 2013, 60, 98–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kessler, R.C.; Berglund, P.; Demler, O.; Jin, R.; Merikangas, K.R.; Walters, E.E. Lifetime Prevalence and Age-of-Onset Distributions of DSM-IV Disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 2005, 62, 593–602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sevillano, L. Resisting the New Yellow Peril: Internalized Racism and Critical Consciousness in Asian, Pacific Islander, Desi Americans. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Texas at Austin, Austin, TX, USA, 2022. embargo in place until May 2027. [Google Scholar]

- Sutton-Brown, C.A. Photovoice: A Methodological Guide. Photogr. Cult. 2014, 7, 169–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Burris, M.A. Photovoice: Concept, Methodology, and Use for Participatory Needs Assessment. Health Educ. Behav. 1997, 24, 369–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yosso, T.J. Whose culture has capital? A critical race theory discussion of community cultural wealth. Race Ethn. Educ. 2005, 8, 69–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- David, E.J.R.; Okazaki, S. The Colonial Mentality Scale (CMS) for Filipino Americans: Scale construction and psychological implications. J. Couns. Psychol. 2006, 53, 241–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rapa, L.J.; Bolding, C.W.; Jamil, F.M. Development and initial validation of the short critical consciousness scale (CCS-S). J. Appl. Dev. Psychol. 2020, 70, 101164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussey, W. Mph Slivers of the Journey: The Use of Photovoice and Storytelling to Examine Female to Male Transsexuals’ Experience of Health Care Access. J. Homosex. 2006, 51, 129–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual. Res. Psychol. 2006, 3, 77–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyer, K.; Willis, R. Looking Back to Move Forward: The Value of Reflexive Journaling for Novice Researchers. J. Gerontol. Soc. Work 2019, 62, 578–585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tobin, G.A.; Begley, C.M. Methodological rigour within a qualitative framework. J. Adv. Nurs. 2004, 48, 388–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hill, C.E.; Thompson, B.J.; Williams, E.N. A Guide to Conducting Consensual Qualitative Research. Couns. Psychol. 1997, 25, 517–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carr, W. Partisanship in Educational Research. Oxf. Rev. Educ. 2000, 26, 437–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roberts, S.O.; Bareket-Shavit, C.; Dollins, F.A.; Goldie, P.D.; Mortenson, E. Racial Inequality in Psychological Research: Trends of the Past and Recommendations for the Future. Perspect. Psychol. Sci. 2020, 15, 1295–1309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holmes, A.G.D. Researcher Positionality—A Consideration of Its Influence and Place in Qualitative Research—A New Researcher Guide. Shanlax Int. J. Educ. 2020, 8, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byrne, D. A worked example of Braun and Clarke’s approach to reflexive thematic analysis. Qual. Quant. 2021, 56, 1391–1412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galderisi, S.; Heinz, A.; Kastrup, M.; Beezhold, J.; Sartorius, N. Toward a new definition of mental health. World Psychiatry 2015, 14, 231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yeh, C.J. Depathologizing Asian American Perspectives of Health and Healing. Asian Am. Pac. Isl. J. Health 2000, 8, 138–149. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Prathikanti, S. East Indians American families. In Working with Asian Americans: A Guide for Clinicians; Lee, E., Ed.; The Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 1997; pp. 79–100. [Google Scholar]

- McBride, M. Health and Health Care of Filipino American Elders. Retrieved from Stanford Geriatric Education Center. 2001. Available online: https://geriatrics.stanford.edu/wp-content/uploads/downloads/ethnomed/filipino/downloads/filipino_american.pdf (accessed on 1 March 2024).

- Torsch, V.L.; Ma, G.X. Cross-Cultural Comparison of Health Perceptions, Concerns, and Coping Strategies among Asian and Pacific Islander American Elders. Qual. Health Res. 2000, 10, 471–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yoo, N.; Nicholson, H.L.; Chang, D.F.; Okazaki, S. Mapping Anti-Asian Xenophobia: State-Level Variation in Implicit and Explicit Bias against Asian Americans across the United States. Socius 2023, 9, 23780231231196517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jackson, S.B.; Stevenson, K.T.; Larson, L.R.; Peterson, M.N.; Seekamp, E. Outdoor Activity Participation Improves Adolescents’ Mental Health and Well-Being during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 2506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, S.; Waters, S.F. Asians and Asian Americans’ experiences of racial discrimination during the COVID-19 pandemic: Impacts on health outcomes and the buffering role of social support. Stigma Health 2021, 6, 70–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kramer, E.J.; Kwong, K.; Lee, E.; Chung, H. Cultural factors influencing the mental health of Asian Americans. West. J. Med. 2002, 176, 227–231. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Yip, K.-S. Chinese concepts of mental health: Cultural implications for social work practice. Int. Soc. Work 2005, 48, 391–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeh, C.J.; Inman, A.G.; Kim, A.B.; Okubo, Y. Asian American families’ collectivistic coping strategies in response to 9/11. Cult. Divers. Ethn. Minor. Psychol. 2006, 12, 134–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noh, S.; Beiser, M.; Kaspar, V.; Hou, F.; Rummens, J. Perceived Racial Discrimination, Depression, and Coping: A Study of Southeast Asian Refugees in Canada. J. Health Soc. Behav. 1999, 40, 193–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atkin, A.L.; Tran, A.G.T.T. The roles of ethnic identity and metastereotype awareness in the racial discrimination-psychological adjustment link for Asian Americans at predominantly White universities. Cult. Divers. Ethn. Minor. Psychol. 2020, 26, 498–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- David, E.J.R. A colonial mentality model of depression for Filipino Americans. Cult. Divers. Ethn. Minor. Psychol. 2008, 14, 118–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phinney, J.S.; Ong, A.D. Conceptualization and measurement of ethnic identity: Current status and future directions. J. Couns. Psychol. 2007, 54, 271–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iwamoto, D.K.; Liu, W.M. The impact of racial identity, ethnic identity, Asian values, and race-related stress on Asian Americans and Asian international college students’ psychological well-being. J. Couns. Psychol. 2010, 57, 79–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sevillano, L.; Macapugay, K. Understanding and dismantling the “model minority” stereotype. In Addressing Anti-Asian Racism with Social Work Advocacy and Action; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Napier, A.D.; Ancarno, C.; Butler, B.; Calabrese, J.; Chater, A.; Chatterjee, H.; Guesnet, F.; Horne, R.; Jacyna, S.; Jadhav, S.; et al. Culture and health. Lancet 2014, 384, 1607–1639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singer, M.K. Applying the concept of culture to reduce health disparities through health behavior research. Prev. Med. 2012, 55, 356–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mahalingam, R.; Rabelo, V.C. Teaching Mindfulness to Undergraduates: A Survey and Photovoice Study. J. Transform. Educ. 2018, 17, 51–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Werremeyer, A.; Skoy, E.; Burns, W.; Bach-Gorman, A. Photovoice as an intervention for college students living with mental illness: A pilot study. Ment. Health Clin. 2020, 10, 237–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Williams, C.D.; Byrd, C.M.; Quintana, S.M.; Anicama, C.; Kiang, L.; Umaña-Taylor, A.J.; Calzada, E.J.; Gautier, M.P.; Ejesi, K.; Tuitt, N.R.; et al. A Lifespan Model of Ethnic-Racial Identity. Res. Hum. Dev. 2020, 17, 99–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stefancic, J.; Delgado, R. Critical Race Theory: An Introduction. Work Pap. Available online: https://scholarship.law.ua.edu/fac_working_papers/47 (accessed on 17 July 2010).

- Price-Feeney, M.; Green, A.E.; Dorison, S.H. Suicidality Among Youth Who are Questioning, Unsure of, or Exploring Their Sexual Identity. J. Sex Res. 2020, 58, 581–588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huey, S.J.; Tilley, J.L. Effects of mental health interventions with Asian Americans: A review and meta-analysis. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 2018, 86, 915–930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lau, A.S.; Chang, D.F.; Okazaki, S. Methodological challenges in treatment outcome research with ethnic minorities. Cult. Divers. Ethn. Minor. Psychol. 2010, 16, 573–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marchand, A.; Beaulieu-Prévost, D.; Guay, S.; Bouchard, S.; Drouin, M.S.; Germain, V. Relative Efficacy of Cognitive-Behavioral Therapy Administered by Videoconference for Posttraumatic Stress Disorder: A Six-Month Follow-Up. J. Aggress. Maltreatment Trauma 2011, 20, 304–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xin, R.; Fitzpatrick, O.M.; Lai, P.H.L.; Weisz, J.R.; Price, M.A. A Systematic Narrative Review of Cognitive-behavioral Therapies with Asian American Youth. Evid. Based Pract. Child Adolesc. Ment. Health 2022, 7, 198–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huynh, T.; Torquati, J.C. Examining connection to nature and mindfulness at promoting psychological well-being. J. Environ. Psychol. 2019, 66, 101370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Javier, J.R.; Galura, K.; Aliganga, F.A.P.; Supan, J.D.; Palinkas, L.A. Voices of the Filipino Community Describing the Importance of Family in Understanding Adolescent Behavioral Health Needs. Fam. Community Health 2018, 41, 64–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- López, G.; Ruiz, N.; Patten, E. Key Facts about Asian Americans, a Diverse and Growing Population. Pew Res Cent. 2017. Available online: https://www.pewresearch.org/short-reads/2021/04/29/key-facts-about-asian-americans/ (accessed on 1 March 2024).

Figure 1.

Roman’s photo for mental health and well-being Photovoice prompt. Note the following caption is written by Roman: Poor mental health translating to physical health problems.

Figure 1.

Roman’s photo for mental health and well-being Photovoice prompt. Note the following caption is written by Roman: Poor mental health translating to physical health problems.

Figure 2.

JellyBean’s photo for mental health and well-being Photovoice prompt. Note the following caption is written by Jellybean: This was a photo I snapped at the end of last semester that I thought represented my mental and physical health situation really well. I’m sure you can see my sunken eyes, as I was extremely tired. This was the only day I went to campus last semester. I’ve had a plethora of health issues since I became a student at UT: pelvic injury that left me unable to walk, anemia that makes me extremely tired, diagnosed with [Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder], and anxiety etc. Last semester was extremely hard for me, I ended up staying at home because I couldn’t deal with my health issues on my own, so I took the photo on the one special day I went to campus.

Figure 2.

JellyBean’s photo for mental health and well-being Photovoice prompt. Note the following caption is written by Jellybean: This was a photo I snapped at the end of last semester that I thought represented my mental and physical health situation really well. I’m sure you can see my sunken eyes, as I was extremely tired. This was the only day I went to campus last semester. I’ve had a plethora of health issues since I became a student at UT: pelvic injury that left me unable to walk, anemia that makes me extremely tired, diagnosed with [Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder], and anxiety etc. Last semester was extremely hard for me, I ended up staying at home because I couldn’t deal with my health issues on my own, so I took the photo on the one special day I went to campus.

Figure 3.

Grand’s photo for mental health and well-being Photovoice prompt. Note that the following caption is written by Grand: The build up of various factors including school and societal pressures can reach the point of needing an extra boost to even get through the day. The can in this example represents the physical need to continue pushing forward no matter what and the mental toll it takes on my well being.

Figure 3.

Grand’s photo for mental health and well-being Photovoice prompt. Note that the following caption is written by Grand: The build up of various factors including school and societal pressures can reach the point of needing an extra boost to even get through the day. The can in this example represents the physical need to continue pushing forward no matter what and the mental toll it takes on my well being.

Figure 4.

Blue’s photo for mental health and well-being Photovoice prompt. Note that the caption is written by Blue: This shows two Asian kids gambling the night before a big test in order to take some of the stress away. This picture was taken to document the serenity of the environment, the sort of calm before the storm before the big test that would determine the grade the boys would receive in their [Management Information Systems] course.

Figure 4.

Blue’s photo for mental health and well-being Photovoice prompt. Note that the caption is written by Blue: This shows two Asian kids gambling the night before a big test in order to take some of the stress away. This picture was taken to document the serenity of the environment, the sort of calm before the storm before the big test that would determine the grade the boys would receive in their [Management Information Systems] course.

Figure 5.

Redacted’s photo for mental health and well-being Photovoice prompt. Note that the caption is written by Redacted: Walking around Austin, being outside helps [de-stress] from studying.

Figure 5.

Redacted’s photo for mental health and well-being Photovoice prompt. Note that the caption is written by Redacted: Walking around Austin, being outside helps [de-stress] from studying.

Figure 6.

Spencer’s Photo (b) for mental health and well-being Photovoice prompt. Note that the caption is written by Spencer: I am pictured taking a photo of the sun setting over Lady Bird Lake. Being outside plays a big role in my mental health. I love to exercise and move my body, but I also love to capture what I see so I can remember it whenever I need a pick-me-up.

Figure 6.

Spencer’s Photo (b) for mental health and well-being Photovoice prompt. Note that the caption is written by Spencer: I am pictured taking a photo of the sun setting over Lady Bird Lake. Being outside plays a big role in my mental health. I love to exercise and move my body, but I also love to capture what I see so I can remember it whenever I need a pick-me-up.

Figure 7.

Spencer’s photo (a) for mental health and well-being Photovoice prompt. Note that the caption is written by Spencer: My friend leans over to look closer at the water at Zilker Park. Walking in nature, and chatting with friends, is the ultimate relaxation. We talk about our weeks, our struggles, our joys, anything is fair game. It is so comforting and encourages me to keep going.

Figure 7.

Spencer’s photo (a) for mental health and well-being Photovoice prompt. Note that the caption is written by Spencer: My friend leans over to look closer at the water at Zilker Park. Walking in nature, and chatting with friends, is the ultimate relaxation. We talk about our weeks, our struggles, our joys, anything is fair game. It is so comforting and encourages me to keep going.

Figure 8.

Eli’s photo for mental health and well-being Photovoice prompt. Note that the caption is written by Eli: This is a picture of my family sitting down to a dinner of Indian food. I took this picture because my family is very important to me and have been a great support system. I am grateful for this as this is not very common in Asian families, where parents are often strict and demanding of their children. Also, mental health is a difficult subject in my family, and while my parents are supportive, they don’t quite understand my relationship with it.

Figure 8.

Eli’s photo for mental health and well-being Photovoice prompt. Note that the caption is written by Eli: This is a picture of my family sitting down to a dinner of Indian food. I took this picture because my family is very important to me and have been a great support system. I am grateful for this as this is not very common in Asian families, where parents are often strict and demanding of their children. Also, mental health is a difficult subject in my family, and while my parents are supportive, they don’t quite understand my relationship with it.

Figure 9.

Lana’s photo for mental health and well-being Photovoice prompt. Note that the caption is written by Lana: I was at the Congress Avenue Bridge here with a goal of taking good pictures. I don’t have a lot of confidence when it comes to my appearance. When I was younger, my relatives with their unrealistic beauty standards would tell me everything that was wrong with my looks. I grew up feeling insecure about my looks, and I became extremely camera shy. I was still working on my confidence while taking this picture. But in the end, I managed to genuinely laugh and my friend captured it.

Figure 9.

Lana’s photo for mental health and well-being Photovoice prompt. Note that the caption is written by Lana: I was at the Congress Avenue Bridge here with a goal of taking good pictures. I don’t have a lot of confidence when it comes to my appearance. When I was younger, my relatives with their unrealistic beauty standards would tell me everything that was wrong with my looks. I grew up feeling insecure about my looks, and I became extremely camera shy. I was still working on my confidence while taking this picture. But in the end, I managed to genuinely laugh and my friend captured it.

Figure 10.

Pastel Pink’s photo (a) for mental health and well-being Photovoice prompt. Note that the caption is written by Pastel Pink: Sing your Heart Out.

Figure 10.

Pastel Pink’s photo (a) for mental health and well-being Photovoice prompt. Note that the caption is written by Pastel Pink: Sing your Heart Out.

Figure 11.

Pastel Pink’s photo (b) for mental health and well-being Photovoice prompt. Note that the caption is written by Pastel Pink: Party Time.

Figure 11.

Pastel Pink’s photo (b) for mental health and well-being Photovoice prompt. Note that the caption is written by Pastel Pink: Party Time.

Figure 12.

Hazel’s photo for mental health and well-being Photovoice prompt. Note that the caption is written by Hazel: This is a follow-up diary entry (also about burnout, written 7 May 2022) describing loneliness now that many people I know are comfortable joining crowds and socializing in groups, whereas I keep quarantining because I’m scared of getting COVID, unwilling to get sick, and too introverted for crowds anyways. This has been a very exhausting school year. I’m in an accelerated master’s of public health program, so I am both [hyper-aware] of COVID and [hyper-aware] that everyone keeps congratulating me for being ‘so smart’ and ‘ambitious!’ but I just feel alone. My public health classes are all online, so I don’t even know my classmates and I don’t have any photos of classrooms to contribute here in this Qualtrics form.

Figure 12.

Hazel’s photo for mental health and well-being Photovoice prompt. Note that the caption is written by Hazel: This is a follow-up diary entry (also about burnout, written 7 May 2022) describing loneliness now that many people I know are comfortable joining crowds and socializing in groups, whereas I keep quarantining because I’m scared of getting COVID, unwilling to get sick, and too introverted for crowds anyways. This has been a very exhausting school year. I’m in an accelerated master’s of public health program, so I am both [hyper-aware] of COVID and [hyper-aware] that everyone keeps congratulating me for being ‘so smart’ and ‘ambitious!’ but I just feel alone. My public health classes are all online, so I don’t even know my classmates and I don’t have any photos of classrooms to contribute here in this Qualtrics form.

Figure 13.

Alphonse’s photo for mental health and well-being Photovoice prompt. Note that the caption is written by Alphonse: I find myself staying at the school library until 2 or 3 am on particularly challenging weeks because I don’t trust myself to work at home after years of bad habits doing schoolwork in bed. So when I do get back to my usual UT apartment I immediately knock out if I even so much as dare step in bed. I appreciate that I’ve found more ways to separate work and school than before rather than letting school follow me home, but the boundary’s only really maintained if I’m extra-diligent with 12-h shifts at school on test weeks and avoiding home as much as possible to prevent taking 8-h ‘naps’ or breaks from exhaustion on particularly challenging weeks of schoolwork. The pose is the usual configuration for me using my phone in bed after school (and usually as a prelude to my inevitable sleepiness not long after).

Figure 13.