1. Introduction

Housing instability and homelessness affect approximately 4 million young people in the U.S annually [

1]. According to recent estimates, 1 in 30 youth between the ages of 13 and 17 and 1 in 10 young adults between the ages of 18 and 25 have experienced some form of homelessness in the past year (collectively, this population is called “youth and young adults”). More alarmingly, about half of these young people experienced homelessness for the first time [

2], suggesting that being forced to leave one’s home is not an uncommon experience among young people today. Further, youth homelessness does not impact young people equally; young people who identify as Black or Latinx; or as lesbian, gay, bisexual, queer/questioning (LGBTQ+); or hold intersectional marginalized identities are at greater risk of experiencing homelessness. Other common factors associated with risks for homelessness include family conflict, early instability, loss of a parent, exits from the child welfare system, and related adversities [

3,

4].

There are many costs to youth and young adult homelessness. For young people, homelessness disproportionately exposes them to interpersonal violence, substance use, and trauma, leading to more physical and mental health needs [

5,

6,

7,

8]. For society, youth homelessness may be linked to young people being disconnected from school and work, leading to lost productivity and civic engagement [

9]. There have been increased federal investments in preventing youth homelessness, but there is no existing research on the characteristics and needs of young people actively in crisis or at imminent risk of becoming homeless. Further, no studies have sought to understand how these young people in crisis or at risk might differ from those who have already left their parents’ or guardians’ homes. To design effective youth homelessness prevention programs, it is critical to understand how these groups of young people may be distinct in their demographic characteristics and needs and, in turn, what services and supports service providers should make available to them to prevent a crisis from escalating and leading to homelessness.

1.1. Youth Homelessness

The Voices of Youth Count (VoYC), a research and policy initiative to understand the scope and scale of youth homelessness in the U.S. [

2], revealed the incidence and prevalence of youth homelessness across the U.S. This study also identified the characteristics of young people actively experiencing homelessness; young people under the age of 25 who were more likely to be homeless included those who were parenting; identified as lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, or queer/questioning; were Black or Hispanic; had less than a high school diploma; or had an annual income of less than

$24,000. Though this study presents a valuable snapshot of the characteristics of young people experiencing homelessness across the U.S., it does not provide any information at a national level about who might be at risk of homelessness. One other study using a quasi-qualitative methodology with 41 young people experiencing homelessness in Australia identified trajectories combining five potential pathways into youth homelessness: psychological disorder, trauma, substance use, crime, and family problems [

10]. The most commonly occurring pathways included trauma and psychological problems, substance use and family problems, and family problems alone. These findings illuminate challenges that many young people faced before they became homeless. Given this small sample size, research on a larger scale is needed to broaden the field’s understanding of the range of opportunities for preventing youth homelessness.

In studies of both young people and adults, race and ethnicity are intertwined with risks for and experiences of homelessness [

11]. Among youth and young adults, there remain persistent disproportionalities in who experiences homelessness; young people who identified as Black had an 83% higher risk and those who identified as Latinx had a 33% higher risk of experiencing homelessness than their White peers [

12]. Further, among young people holding intersectional marginalized identities (i.e., their racial/ethnic identity, gender identity, and sexual orientation), risks for youth homelessness were considerably higher. In fact, young people who identified as Black and LGBTQ+ experienced the highest rates of homelessness—16% compared to 4% of White, heterosexual, and cisgender young people. Research examining the explanation for these long-standing racial/ethnic disparities pinpoints three drivers, including economic inequality along racial lines, housing discrimination resulting in residential segregation, and the operations of homeless response systems [

13]. These findings make clear that preventing and mitigating the effects of youth homelessness are critical equity issues.

There is robust evidence on the experiences and circumstances that young people face that may put them at risk for homelessness. A mix of qualitative and quantitative studies have revealed that young people who were homeless faced family violence and conflict, systems involvement, and early instability before they became homeless [

4]. Many young people reported leaving their homes because of family violence or conflict [

14,

15,

16], and others were asked to leave or rejected because of their sexual orientation or gender identity [

3]. Still others faced challenges exiting systems of care, including the child welfare system and the juvenile justice system [

4,

17], or were engaging in risky behaviors before becoming homeless [

17,

18,

19]. Most of these studies are retrospective and have involved asking young people experiencing homelessness about the challenges they faced before they became homeless. However, little is known about the types of needs young people have while they are actively in crisis and while they are considering running away, and whether those needs differ from those of young people who are currently experiencing homelessness.

1.2. A Prevention Framework

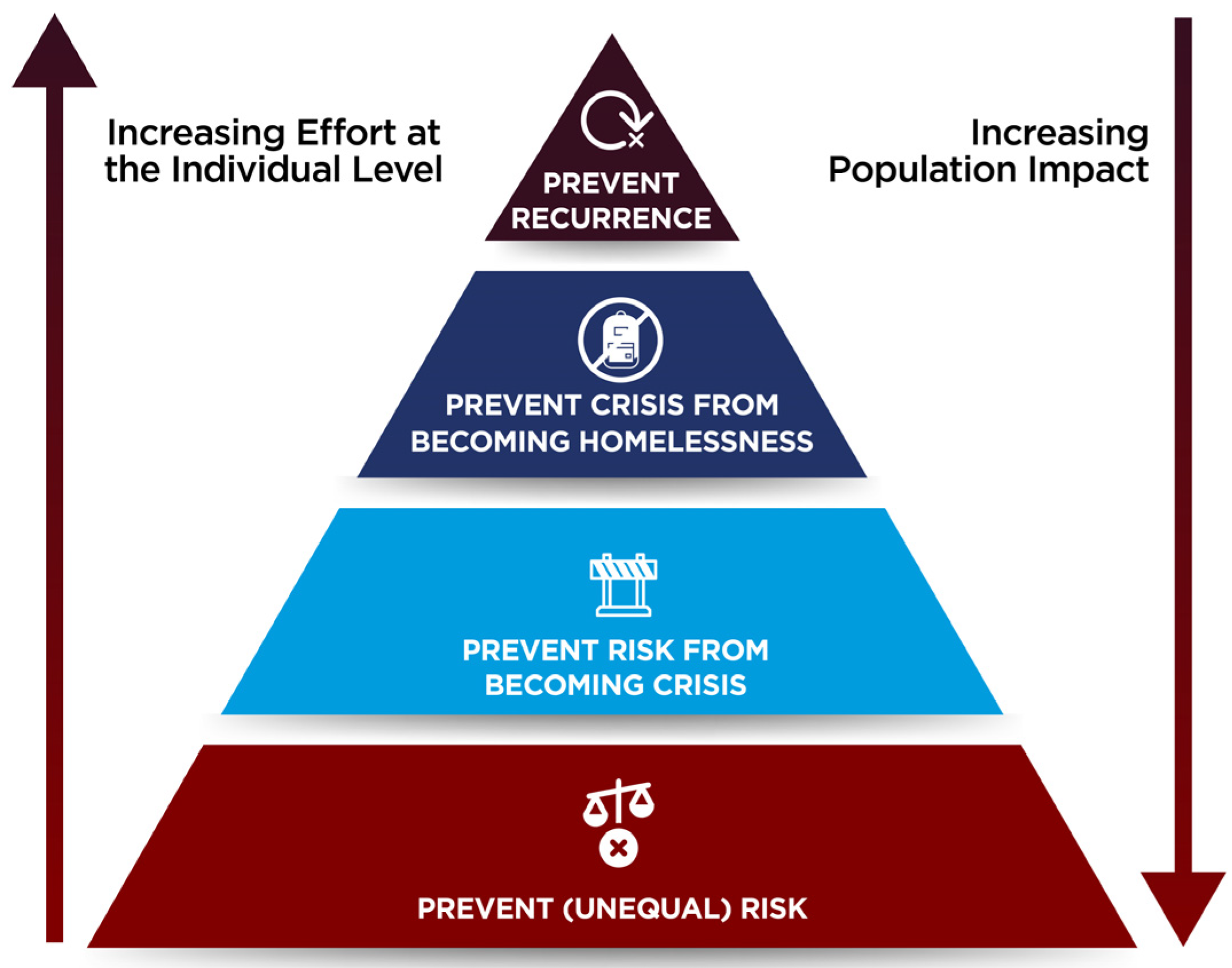

In their public health model for youth homelessness prevention, Farrell and Morton [

20] outline a four-tier prevention model (

Figure 1) adapted from Frieden’s public health impact pyramid [

21]. The lower tiers focus on structural factors that have broader population impact, such as policies, while the top tiers require increasing effort at the individual levels, such as through targeted interventions like housing voucher programs.

The base level, Tier 1, includes structural conditions that create unequal risk for homelessness. This level addresses the various structural factors, such as racial economic inequality, housing discrimination, and residential segregation, which have led to disparities in intergenerational wealth, housing stability, and social capital [

13,

22]. Tier 1 also includes other social determinants of health, including education, healthcare, social and community well-being, and the built environment [

23]. Much of the drivers of racial/ethnic disparities in youth homelessness sit in this tier, since racism has an undeniable influence on individual and community socioeconomic status, which subsequently drive health inequities through social determinants of health [

24]. Interventions in Tier 1 are viewed as “upstream” investments in systems change, such as policies that reduce disparities in predictors of homelessness (e.g., equitable employment opportunities [

25]) or specific programs like increased access to housing vouchers.

Tiers 2 through 4, which involve increased effort at the individual level and decreased population impact, represent unique opportunities for prevention and intervention. Tier 2 captures common pathways for risk to become crisis, such as addressing existing forms of adversity that young people and their families face that may eventually result in homelessness. Opportunities for preventing homelessness in this domain include ensuring that young people who leave the child welfare system and juvenile justice system have housing plans and supports for living on their own, as well as broader screening for material, physical, and mental health needs in doctors’ offices and schools so that emerging needs can be remedied in a timely fashion to keep a potential crisis at bay.

Tier 3 spotlights crises that lead to homelessness, which may involve interventions to quickly stabilize a young person who is about to lose their housing so that they can avoid entering the homelessness system through a shelter or other entry point. This may involve family mediation, greater investments in coordinated responses systems, direct cash transfers, and the availability of resources through local programs such as youth drop-in centers that help young people obtain immediate access to permanent housing options before the crisis at hand results in homelessness.

Finally, Tier 4 includes interventions to reduce the duration and harm and ensure access to permanent housing, thereby preventing the recurrence of homelessness. Young people who are already homeless need access to safe and stable housing, such as long-term rapid rehousing or housing voucher programs, that would give them an adequate runaway to stabilize their lives through educational and employment opportunities before facing high costs of living and unaffordable housing on the private market. Taken together, it is clear that preventing youth and young adults from experiencing homelessness, or experiencing it again, may require different types of services and resources depending on young people’s ongoing challenges and needs, but little is known about the characteristics, circumstances, needs, and opportunities among young people encountering adversities that could lead to homelessness.

1.3. Federal Investments in Preventing Youth Homelessness

Over the past few years, the U.S. government increased its investment in prevention initiatives for a range of social problems, including adolescent pregnancy [

26], human trafficking [

27], and homelessness [

28]. The Family and Youth Services Bureau (FYSB) in the Administration of Children and Families in the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) is responsible for funding the Runaway and Homeless Youth (RHY) program. Each year, FYSB awards approximately 600 grants to youth services providers across the country to provide street outreach, basic center, and transitional living programs, as well as maternity group homes for pregnant and parenting youth [

29].

During the 2024 fiscal year, FYSB funded a new program model as part of the RHY portfolio of programs, called the Prevention Demonstration Programs (PDP) [

29]. The PDP grants are designed to help communities build coordination across public agencies, such as school systems and child welfare agencies, and youth service providers though a collaboratively developed and executed prevention plan that includes case management, referrals for services (e.g., mental health counseling), and flexible cash assistance. Since there are currently very few programs that have empirically demonstrated effectiveness at reducing youth homelessness in the U.S. [

30], evaluation of these programs will be critical to informing the field about how to address crises young people face before they become homeless. Understanding the populations that these programs may serve, in terms of who these young people are and what supports they need, is a high priority.

Another federal investment in preventing youth homelessness is the National Runaway Safeline (NRS), an organization whose mission is to ensure that young people experiencing or at risk of homelessness have the resources they need to avoid becoming homeless or quickly resolving an experience of homelessness [

31]. The NRS operates the federally funded national communication system for youth ages 12 to 21 in the U.S. who are at risk of or experiencing homelessness. The NRS has five methods of communication—calls, emails, texts, chats, and forum posts—through which frontline staff offer trauma-informed, non-judgmental, non-sectarian, and non-directive supports, including crisis intervention services, referrals, and other forms of assistance to young people and their friends or family reaching out on their behalf. Young people across the U.S. states and territories can reach NRS frontline staff 24 hours a day, 7 days a week, 365 days a year. Further, the NRS has a range of individual programs they offer, including Home Free, a partnership with Greyhound Lines, Inc. to help young people reconnect with their families or get to a safe alternative living arrangement; “Let’s Talk”, a 16-module runway prevention program; a messaging service that allows young people or their family members to indirectly reach out to each other as a first step towards mediation and reunification; a conference calling service where the NRS can serve as a mediator between a young person and their parent/guardian; as well as other educational and informational materials. Additionally, the NRS manages a database of approximately 7500 resources that frontline staff can provide as referrals to address the needs of young people and their families, including counseling, shelters, and substance use services, among others. Annually, the NRS experiences the largest volume of contacts from heavily populated states, such as California, Texas, and Florida, with increased usage in recent years across Midwestern states such as Illinois, Michigan, and Ohio [

32].

1.4. Current Study

Evidently, there is little known about the range of challenges facing young people and their needs that might precede an experience of homelessness. To date, the literature has primarily focused on young people actively experiencing homelessness and their current and retrospective reflections on what they needed while they were homeless or on the brink of becoming homeless. No literature of which we are aware has sought to describe the characteristics or needs of young people across homelessness risk categories even though interventions for young people in these groups may vary based on their specific needs. For service providers to begin developing effective solutions to preventing youth homelessness, it is necessary to first understand the characteristics and experiences of young people requiring various types of prevention or intervention efforts.

To address this critical question, a research team comprising staff from Chapin Hall at the University of Chicago and the NRS partnered to leverage the NRS’s crisis services and prevention data. The NRS characterizes young people who reach out for support as in crisis, contemplating running away (i.e., at imminent risk of homelessness), and currently homeless, which map onto Tiers 2 through 4 on the public health impact model for youth homelessness [

20]: Tier 2 (preventing risk from becoming a crisis = “in crisis”), Tier 3 (preventing a crisis from becoming homelessness = “contemplating running”), and Tier 4 (preventing recurrence of homelessness = “currently homeless”). Thus, this study aims to address three research questions to illuminate the characteristics, circumstances, needs, and service referrals of young people who are in crisis, who are at risk of experiencing homelessness, and who are homeless using a prevention framework:

To what extent are demographic characteristics, previous experiences of homelessness, and location of outreach associated with homelessness risk (i.e., in crisis, contemplating running, currently homeless)?

How are the types of presenting problems that young people report experiencing associated with homelessness risk?

How is homelessness risk associated with types of service referrals that young people receive?

Given the lack of existing literature on young people who are in crisis and at imminent risk of becoming homeless, compared to the large body of research on youth actively experiencing homelessness, this study is exploratory in nature and we do not pose specific hypotheses.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Procedures

Data for this study were drawn from the information that the NRS captures through engagement with young people and those reaching out on their behalf (“contacts”) (for additional information on this dataset, see the “2022 Crisis Services & Prevention Report” [

33]. The NRS uses two data collection forms, one for online chats and one for hotline calls (i.e., the telephone service), emails, and forum posts. The data form permits frontline staff on the Crisis Services team to collect information that contacts voluntarily share while involved in a crisis intervention exchange; the data form is not a structured or standardized interview protocol. Frontline staff generally seek to understand demographic information about contacts, and the young person in crisis, if they are not calling on their own behalf, as well as the main presenting problems. Additionally, frontline staff attempt to understand whether a young person has had previous systems involvement (e.g., child welfare, juvenile justice), how they learned about the NRS, and, if contacts are homeless, how long they have been homeless and how they are surviving while homeless. The NRS maintains a directory of over 7500 programs in local communities that can support young people and their families. Crisis Services team members discuss possible referral options and next steps with contacts to help address their needs, connecting them with available resources as needed. Through the course of these interactions, frontline staff strategically record relevant information about each contact and their needs to understand how the NRS might help them and what types of referrals would best suit them.

The first author maintains a research partnership with the NRS, which involves analyzing their annual crisis intervention and prevention services data to produce a report to the Family and Youth Services Bureau in the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. The present study emerged as part of this partnership and was approved by the University of Chicago Crown Family School of Social Work, Policy, and Practice/Chapin Hall Institutional Review Board.

2.2. Participants

This study uses NRS crisis intervention services data collected from 1 January through 31 December 2022. There were 26,198 contacts from hotline calls, emails, forum posts, and chats involving young people aged 21 and under. We excluded 95 cases labeled “pranks” and 4463 records in which someone else called on behalf of a young person in crisis. We further limited the sample to young people who had valid data on referrals and type of caller (dropping an additional 10,074 cases), which reflected full engagement with the NRS’s frontline staff on crisis intervention opportunities. The analytic sample for this study was N = 11,566.

2.3. Measures

Homelessness risk. NRS frontline staff captured the status of young people who reach out to the NRS as contemplating running, homeless, runaway, suspected missing, asked to leave, and youth in crisis. We created a categorical variable that combined homeless, runaway, suspected missing, and asked to leave into “homeless” = 1, with “contemplating running” = 2, and “in crisis” = 3. The NRS distinguishes young people who are contemplating running as at imminent risk for homelessness due to housing- and safety-related issues and young people in crisis as those who are facing other challenges that are not immediately likely to result in homelessness or not specific to housing instability. The homelessness risk categorical variable was constructed to align with Tiers 2 through 4 of the adapted public health impact pyramid [

20].

Demographic characteristics. Demographic characteristics included race/ethnicity, gender identity, age, and their current location. Race/ethnicity was coded categorically for 1 = “American Indian/Alaska Native”, 2 = “Asian”, 3 = “Black/African American”, 4 = “Hispanic/Latinx”, 5 = “Multiracial”, 6 = “Hawaiian/Pacific Islander”, and 7 = “White/Caucasian”. Gender included 1 = “female”, 2 = “male”, and 3 = “transgender/nonbinary”. Age was also coded categorically, where 1 = “under 12”, 2 = “12–14”, 3 = “15–17”, 4 = “18–21”, and 5 = “22+”. Additionally, young people reported on the location they were reaching out from, which included 1 = “home”, 2 = “friend or relative”, 3 = “school or work”, 5 = “other”, and 6 = “unknown”. Other categories were infrequently reported and included detention/police, Greyhound bus station, pimp/dealer, recent acquaintance, shelter, street/payphone, and “other”.

Previous experiences of homelessness. Contacts could share whether they had previously been homeless, prior to reaching out to the NRS, coded as 0 = “no” and 1 = “yes”.

Presenting problems. During their crisis intervention exchange with the NRS’s frontline staff, contacts can discuss the reasons for reaching out and other ongoing challenges in their lives. NRS staff can select from a range of specific experiences within sixteen categories including: alcohol/substance use, economics (e.g., employment challenges), emotional abuse, exploitation (e.g., trafficking), family dynamics (e.g., family conflict), health, justice system, LGBTQ+ issues, mental health, neglect, peers (e.g., gang involvement), physical abuse, school issues (e.g., problems with students or teachers), sexual abuse, transportation, and youth and family issues (i.e., issues within the child welfare system). The categories of presenting problems are not mutually exclusive, and each category is coded as 0 = “no” and 1 = “yes”.

Referral options. Following a discussion of presenting problems, the NRS’s frontline staff discuss potential referral options with contacts. Frontline staff may make a variety of referrals to specific services, which are presented in

Table 1. The categories of referral options are not mutually exclusive, and each category is coded as 0 = “no” and 1 = “yes”.

2.4. Analytic Plan

Since contacts voluntarily share information, including demographic information, the amount of valid data varies across variables of interest. Missing data ranged from 7% on presenting problems to 45% on race/ethnicity to 71% on previous homelessness. Given the high percentage of missingness in demographic characteristics, sample sizes for each analysis ranged from N = 2316 for RQ1 to N = 6507 for RQ3. To address concerns about missing data, we examined the subsample of contacts with missing demographic data through a series of crosstabulations between this population and other key variables of interest. There were few discernible patterns, but it was evident that 54% of the cases with missing demographic data came through the telephone service compared to 10% via email, 18% via forum posts, and 17% via live chat. Since the NRS’s Crisis Services team embodies a model to engagement that is trauma-informed and non-directive, which means that frontline staff aim to let young people be in control of the conversation, deciding what they feel comfortable sharing to encourage them to feel empowered to make their own decisions. At the completion of each call, the Crisis Services team tries to collect five key data points that are needed to inform suggested referrals and potential program eligibility (i.e., location, age, gender, race/ethnicity, how learned of the NRS); however, since demographic data are not missing at random or completely at random, we could not use multiple imputation for these analyses. This sample represents an epidemiological sample of young people in crisis, so we conducted a complete case analysis for each research question.

To address the first research question exploring factors associated with homelessness risk type, we used a multinomial logistic regression analysis to predict membership in the homelessness risk categories based on young people’s demographic characteristics (i.e., race/ethnicity, gender, age), previous homelessness, and location from which they reached out to the NRS. Multinomial logistic regression permits estimation of nominal outcomes with two or more categories and produces relative risk ratios [

34]. Risk ratios over 1.0 reflect a greater risk of a problem or a referral, and values below 1.0 reflect a lower risk of reporting. We estimated a model in which homeless was the base (reference) category to predict membership in the contemplating running and in crisis categories and subsequently changed the base category to assess relations between the other categories. For categorical predictor variable, we also re-estimated the model with different base categories to test for all possible significant differences, presented as superscript numerals in

Table 2.

To address the second research question, we again used multinomial logistic regression analyses to predict membership in the homelessness risk categories from young people’s reports of the problems they were experiencing. These models controlled for demographic characteristics, including their race/ethnicity, gender identity, and age. We used the same process of model estimation described above to ensure that we tested all comparisons among categories.

Finally, to address the third research question on the types of referrals that young people with varying homelessness risk received, we used logistic regression analyses predicting types of referrals, controlling for demographic characteristics. These analyses drew on the top ten most common referrals, of which at least 18% of contacts reported receiving, including adults, alternate youth housing, child abuse hotline, family, friends, Transitional Living Program, NRS services, police, self-help, and social services. To facilitate interpretation of the logistic regression results, we transformed odds ratios to risk ratios. All analyses were conducted in Stata version 18.0 [

35].

3. Results

3.1. Sample Descriptives

Descriptive information on the entire sample and by homelessness risk category are shown in

Table 1. This table presents demographic characteristics, previous experiences of homelessness, the location from which young people reached out to the NRS, prevalence of presenting problems, and percentage of young people who received each type of referral that NRS frontline staff make to crisis intervention contacts. One fifth (21%) of the young people who reached out to the NRS were homeless, one third (33%) were contemplating running, and fewer than half (46%) were in crisis.

3.2. Relations among Demographic Characteristics, Previous Experiences of Homelessness, Location of Outreach, and Homelessness Risk

Results from the multinomial logistic regression analyses addressing the first research question are presented in

Table 2. Race/ethnicity did not put young people at risk for any of the homelessness risk categories. Young people who identified as male (

RR = 1.45,

p < 0.01) or transgender (

RR = 1.36,

p < 0.05), compared with females or those who had a previous experience of homelessness were more significantly likely to be contemplating running than homeless (

RR = 1.64,

p < 0.05). Those with a previous experience of homelessness were also significantly more likely to be contemplating running than in crisis (

RR = 1.80,

p < 0.001). Young people who were 18–21 years old were significantly less likely to be contemplating running than homeless (

RR = 0.14,

p < 0.001) and significantly less likely to be contemplating running than in crisis (

RR = 0.10,

p < 0.01). Young people who were older than 21 were significantly less likely to be contemplating running than homeless (

RR = 0.07,

p < 0.05) and significantly less likely to be contemplating running than in crisis (

RR = 0.09,

p < 0.01).

Reaching out to the NRS from anywhere other than home was consistently significantly associated with a lower likelihood of both contemplating running and being in crisis, as compared to being homeless. Those who called from the home of a friend/relative (RR = 0.002, p < 0.001), school/work (RR = 0.03, p < 0.001), some other place (RR = 0.001, p < 0.001), or an unknown location (RR = 0.04, p < 0.001), were significantly less likely to be contemplating running than homeless. Those who reached out to the NRS from the home of a friend/relative (RR = 0.01, p < 0.001), school/work (RR = 0.04, p < 0.001), some other place (RR = 0.01, p < 0.001), or an unknown location (RR = 0.01, p < 0.001) were significantly less likely to be in crisis than homeless. Young people who reached out to the NRS from the homes of their friends/relatives (RR = 0.17, p < 0.001) or some other place (RR = 0.14, p < 0.001) were also significantly less likely to be contemplating running than in crisis. Additionally, those who reached out from an unknown location (RR = 2.63, p < 0.01) were significantly more likely to be contemplating running than in crisis.

3.3. Associations between Homelessness Risk and Types of Presenting Problems

Table 3 presents the results of the multinomial logistic regression analysis that assessed the likelihood of membership in each homelessness risk categories based on the types of presenting problems young people reported to the NRS, controlling for demographic characteristics. Alcohol and substance use were significantly associated with a lower likelihood of contemplating running (

RR = 0.64,

p < 0.05) and being in crisis (

RR = 0.65,

p < 0.05), as compared to being homeless. Economics were similarly significantly associated with a lower likelihood of contemplating running (

RR = 0.18,

p < 0.001) and being in crisis (

RR = 0.19,

p < 0.001), as compared to being homeless. Exploitation was only significantly associated with a lower risk of contemplating running (

RR = 0.09,

p < 0.05), as compared with homelessness. Family dynamics were strongly and significantly associated with contemplating running (

RR = 2.79,

p < 0.001) and being in crisis (

RR = 2.45,

p < 0.001), compared to being homeless. LGBTQ+ issues (

RR = 1.65,

p < 0.05) and peer concerns (

RR = 1.30,

p < 0.01) were significantly associated with a greater likelihood of contemplating running, as compared with being homeless. Physical health was significantly associated with a lower likelihood of contemplating running (

RR = 0.73,

p < 0.01), as compared with being homeless, and school issues were significantly associated with a greater likelihood of contemplating running (

RR = 1.91,

p < 0.001), as opposed to being in crisis. Youth and family issues, which are related to child welfare system involvement, were significantly associated with a lower likelihood of contemplating running (

RR = 0.59,

p < 0.01), as compared to being in crisis, and a higher likelihood of being in crisis (

RR = 1.36,

p < 0.05), as compared with homeless.

Emotional abuse, mental health, and neglect were significantly associated with all three homelessness risk categories. Emotional abuse was associated with a greater likelihood of contemplating running (RR = 2.60, p < 0.001) and being in crisis (RR = 1.55, p < 0.001), compared to being homeless. Emotional abuse was also associated with as contemplating running (RR = 1.67, p < 0.001), compared to being in crisis. Mental health was significantly associated with a greater likelihood of contemplating running compared with being homeless (RR = 1.34, p < 0.01) and being in crisis (RR = 1.69, p < 0.001), but a lower likelihood of being in crisis (RR = 0.79, p < 0.05), as compared with being homeless. Neglect was associated with a lower likelihood of contemplating running, compared with being homeless (RR = 0.73, p < 0.001) and being in crisis (RR = 0.68, p < 0.01), as well as a lower likelihood of being in crisis than being homeless (RR = 0.79, p < 0.05). Reports of health, sexual abuse, and transportation as presenting problems were not associated with homelessness risk.

3.4. Associations between Homelessness Risk and Types of Service Referrals

The results of the logistic regression analyses predicting the likelihood of receiving specific types of referrals based on their homelessness status, and controlling for demographic characteristics, are split into

Table 4. As compared with young people who were homeless, young people who were contemplating running were significantly more likely to receive referrals for adults (

RR = 1.95,

p < 0.05), family (

RR = 1.67,

p < 0.05), friends (

RR = 1.26,

p < 0.05), police (

RR = 1.19,

p < 0.05), and self-help (

RR = 1.91,

p < 0.05) and were significantly less likely to receive referrals for alternate youth housing (

RR = 0.77,

p < 0.05), transitional living programs (

RR = 0.49,

p < 0.05), and social services (

RR = 0.83,

p < 0.05).

As compared with young people who were homeless, those in crisis were significantly more likely to receive referrals for adults (RR = 1.55, p < 0.05) and self-help (RR = 1.96, p < 0.05) and were significantly less likely to receive referrals for alternate youth housing (RR = 0.46, p < 0.05), the child abuse hotline (RR = 0.76, p < 0.05), friends (RR = 0.84, p < 0.05), Transitional Living Programs (RR = 0.46, p < 0.05), and social services (RR = 0.75, p < 0.05).

As compared with young people who were in crisis, young people who were contemplating running were significantly more likely to receive a referral for adults (RR = 1.37, p < 0.05), alternate youth housing (RR = 1.54, p < 0.05), a child abuse hotline (RR = 1.16, p < 0.05), family (RR = 1.16, p < 0.05), friends (RR = 1.38, p < 0.05), and police (RR = 1.22, p < 0.05). Those who were contemplating running were also significantly less likely to receive a referral to services from the NRS (RR = 0.98, p < 0.05), though the magnitude of this association was small.

4. Discussion

This study highlights the unique characteristics, circumstances, needs, and opportunities among young people who were facing varying degrees of risk related to homelessness and who reached out to the NRS, a critical service that helps young people in the U.S. at imminent risk of or experiencing homelessness to connect with needed supports. The results of these analyses point to valuable opportunities for prevention across the top three tiers of the adapted public health pyramid for youth homelessness prevention [

20], with evidence underscoring the need for various types of prevention programs, including those that prevent the recurrence of homelessness, that keep young people from running away, and that mitigate the crises that young people face daily.

Regarding the first research question, which examined the demographic characteristics, previous experiences of homelessness, and location of outreach associated with homelessness risk, findings showed that racial/ethnic group was not associated with membership in a homelessness risk category, and identifying as male or transgender was only associated with an elevated risk of contemplating running. Interestingly, young people over the age of 17 and those with previous experiences of homelessness were more likely to be contemplating running than to be in crisis or already homeless. This aligns with previous research showing that young people’s experiences of homelessness are fluid [

36] and that over two million young people annually experience homelessness for the first time [

2]. Further, young people who connected with the NRS from outside the home of their parent or guardian were more likely to be homeless, highlighting how critical this individual piece of information is for promoting Tier 2 and Tier 3 prevention opportunities to young people who are at home when they engage with the NRS and could benefit from supports that mitigate youth’s adversities or resolve a crisis.

In this analysis, it was surprising not to see any connection between race/ethnicity and the homelessness risk categories, especially given the entrenched nature of the relationship between race/ethnicity and homelessness [

13,

37], even among young people [

11]. However, it is important to note that due to histories of racial economic inequality, housing discrimination, and residential segregation, race/ethnicity is confounded with experiences of homelessness and housing instability, such as ffa previous experience of housing instability [

4]. Thus, it is possible that the inclusion of various characteristics and experiences in this set of analyses obscured the link between young people’s race/ethnicity and their homelessness risk status. In fact, descriptive findings in

Table 1 showed that individuals who identified as Black were disproportionately likely to be homeless, with Black youth and young adults comprising 27% of the analytic sample but 37% of young people who reported being homeless. This finding is in line with previous literature [

2,

11].

The second research question investigated how types of presenting problems that young people reported experiencing were associated with homelessness risk. Those who reported challenges with economics, such as employment and housing, more exposure to alcohol and substance use, experiences of exploitation such as trafficking, involvement in the justice system, or mental health concerns, as well as neglect and physical abuse, were more likely to be homeless. These findings are in accordance with the extant literature on challenges young people encounter while they are homeless [

38]. Reports of emotional abuse, LGBTQ+ topics (e.g., coming out, harassment or abuse, etc.), mental health issues, peer issues (e.g., relationships, problems with friends, sexual activity, etc.), and school issues (e.g., bullying, problems with students or teachers, skipping school, etc.) were more commonly associated with contemplating running. Adolescence and early adulthood is a challenging time for many young people; this developmental stage presents interpersonal challenges within friendships and intimate relationships while young people are trying to understand and make sense of who they are [

39]. Findings on youth who are contemplating running appear to point to the types of developmental tasks that youth and young adults grapple with in their social environments that may be associated with the desire to leave home. Finally, challenges related to young people’s home lives, such as exposure to alcohol/substance use among family members, family conflicts and separations, emotional abuse and neglect, issues with the child welfare system and other services, as well as employment challenges, were related to being in crisis. These results reflect the literature on adverse child experiences [

40] and the capacity for family adversity to de-stabilize young people at a critical turning point in their lives [

4].

The third research question explored how membership in a homelessness risk category was associated with the different types of service referrals that young people received. As expected, those who were already homeless were more likely to be referred to housing programs such as alternate youth housing and transitional living programs, as well as social services and other connection points, such as a child abuse hotline. Young people who were contemplating running were more likely to receive referrals to supports in their social environments, such as adults, family, friends, as well as self-help and the police. Additionally, young people who were categorized in this sample as in crisis were more likely to receive referrals to connect with adults and self-help. Nearly all young people who reached out to the NRS, regardless of risk status, received referrals to continue engaging with the NRS’ services.

Because there is very limited research on how to prevent crises that lead to homelessness [

30], none of which we are aware that describe targeting services to young people based on their level of risk, it is unclear whether the referrals offered to young people in crisis or contemplating running are in fact the right types of services to mitigate the issues at hand. Ongoing work across the country to prevent youth and young adult homelessness at the community [

20,

29,

41] and state levels [

42] has explored employing screening practices for risks for homelessness in schools, partnering with other local systems, and developing a homelessness prevention and diversion fund (HPDF) to connect young people with cash assistance to stabilize their lives. An ongoing set of initiatives is currently exploring the potential for cash to serve a prevention purpose in seven communities across the country [

41], but to date, only one cash assistance program in Washington state, the HPDF program, has demonstrated efficacy at preventing young people at imminent risk of homelessness from losing their homes [

42].

Given that half (51%) of young people were still at home when they reached out to the NRS, there are clear opportunities for homelessness prevention among those who were in crisis and contemplating running, as well as opportunities to prevent recurrence of homelessness among those who had already become homeless. Since many young people in crisis and contemplating running reported challenges related to emotional abuse and family dynamics, there is an apparent avenue for prevention programs that effectively strengthen permanent connections. For some young people, these connections may not be with the family members who have exposed them to abuse or rejection and may instead be with “chosen family”, which are nonfamilial relationships that reflect the structure and functioning of nuclear families [

43]. Emerging research has highlighted host homes as a potential way for young people who are contemplating running or homeless to be formally placed in a room hosted in the home of a volunteer, extended family member or friend as short- or long-term housing support [

44,

45].

Host homes are one example of the ways in which critical connection points, like the NRS, can help young people facing challenges in their lives lean into the natural supports that are available to them and strengthen connections to trusting, caring, and empathic adults in their social networks. These efforts may take place in the proximal domains of young people’s lives, but there are also opportunities for investments at the federal level to build system partnerships within HHS between FYSB and the Children’s Bureau, which is responsible for oversight of the states’ child welfare systems. The recently implemented Family First Prevention Services Act [

46,

47] provides resources for prevention services such as mental health programs, substance use treatment, in-home parent skill-based programs, and kinship navigation. It may be possible that these types of programs work to strengthen families, thereby preventing both child welfare system involvement as well as youth and young adult homelessness. Building a bridge between FYSB and the Children’s Bureau to permit access to these programs for young people at risk of homelessness may ultimately lead to stronger and more cohesive families over time. Given that millions of reports of child abuse are unsubstantiated each year [

48], this may present an opening to redirect families into more appropriate supports that could help prevent youth from wanting to run away or being asked to leave their homes.

The major limitation in this study is that these data draw on a sample of young people who specifically reached out for support from the NRS and are not generalizable to the entire population of young people in crisis. We are also uncertain of the extent to which these data are reflective of the population of young people at risk for or experiencing homelessness because of the considerable missing data on key demographic characteristics, namely race and ethnicity. With an inability to impute these data since they are not missing at random, our sample sizes for some analyses were limited. As such, this limits our statistical power to detect statistically significant differences between these groups of young people. More concerningly, the lack of self-reported racial/ethnic data prohibits us from understanding the racial/ethnic differences across these categories of homelessness risk that might point to opportunities for equitable solutions to prevent young people from facing unnecessary trauma and instability. A third limitation is related to our inability to assess the reliability of the NRS’s staff’s categorizations of young people as homeless, contemplating running, and in crisis, though staff do undergo extensive training. As information is voluntarily shared, the Crisis Services team categorizes the homelessness risk status of young people based on the information they directly share.

Using a cross-sectional design, this study moves beyond previous research focused on youth who were already homeless and reflecting on the missed opportunities for prevention as their crises escalated into homelessness. We leveraged the public health prevention framework for youth homelessness and its clear linkages with a unique dataset. Through this approach, we were able to assess snapshots of young people’s experiences of risk and crisis at three tiers of the prevention pyramid to illuminate different types of needs and opportunities for young people facing different types of homelessness risk. Future research should use this prevention framework for longitudinal research to understand how young people move through these prevention tiers. This work would involve investigation of the characteristics, circumstances, and problems that emerge over the course of young people’s lives that put them at risk for homelessness and identify what types of prevention services and resources helped to mitigate the challenges they faced. Research should also continue to evaluate prevention initiatives to build a rigorous evidence base on what works and for whom when it comes to homelessness prevention. Additionally, the NRS should continue to explore technological solutions to expand opportunities for contacts to self-report on their demographic characteristics, such as the use of the pre-chat survey that asks contacts to describe themselves before they connect with a member of the Crisis Services team. This information has important implications for research purposes and for quality improvement processes related to the crisis services program.

5. Conclusions

This study drew on a unique dataset—the crisis intervention and prevention services data captured by the NRS through their engagement with young people facing varying levels of homelessness risk—to illuminate differences in their characteristics and circumstances, their needs, and the referrals they received. In terms of demographic characteristics, young people who were older and reaching out from anywhere other than home were more likely to be homeless, and those who were male and LGBTQ+ were more likely to be contemplating running. Young people who were homeless were more likely to report needs in the domains of economics, which includes housing and employment, and neglect, whereas young people contemplating running and in crisis were more likely to report issues with family dynamics and emotional abuse; further, young people contemplating running were more likely than those in crisis to indicate mental health needs and school problems, suggesting the presence of untenable home and school situations. Additionally, young people who were homeless were more likely to be referred to youth housing programs and social services, in line with their priority needs, whereas young people in crisis and contemplating running were more likely to be referred to supports that could help address family and community challenges, such as adults, self-help, and friends and family.

Taken together, these findings point to critical opportunities for investments at local, state, and federal levels to implement programs that are theoretically and strategically aligned with the adapted public health impact pyramid for youth homelessness prevention [

20]. This means that local and state policy makers should work together across youth and family focused agencies to ensure that local investments in programs that support young people promote sustainable exits from homelessness as well as homelessness prevention and diversion. At the federal level, HHS and HUD currently fund programs focused on youth homelessness prevention, but community-based initiatives could be better aligned with these programs to yield a coherent and comprehensive array of youth homelessness prevention services. Clearly, young people’s lives evolve in ways that may put them at risk for crises, for risks for homelessness, or for cycles of homelessness; this study underscores the need to meet young people where they are to resolve the issues at hand and to help them remain safely, stably, and securely housed.