Abstract

Mindfulness is regarded as a systematic process of shaping the innate quality of the mind primarily practised through meditation. As a result, this paper aims to uncover the nature and spirit of mindfulness practice, which should go beyond clinical intervention or disciplined practices, to explore how self-care techniques like food preparation, knitting, and mindfulness exercises can be incorporated into home economics education. The current review found 12 research papers with statements about cooking and 6 on crafting/knitting. Beyond mindfulness eating, the retrieved papers in the current review have captured a few studies that put forward the elements of mindfulness in cooking. Nonetheless, most papers did not treat cooking as a mindfulness practice, but rather as a self-care practice that resulted in similar psychological factors such as awareness, behavioural changes, and self-efficacy. Moreover, the studies and documentation of crafts in home economics education, such as knitting, sewing, and needlepoint, have been described as mindfulness-based activities. Additionally, it acts as a type of self-care by calming down, alleviating tension, and encouraging relaxation. Therefore, home economics classes should be promoted in schools, and self-care and mindfulness exercises should be added to the curriculum.

1. Introduction

According to Jon Kabat-Zinn, Mindfulness-Based Stress Reduction (MBSR) therapy pioneer [1], mindfulness refers to the thought of the current moment, which involves non-judgmental awareness of the present moment [2]. It has been used in clinical settings to increase well-being and lessen stress, anxiety, and depression as mindfulness serves as an essential way to access the intricacies of one’s internal mind, ultimately leading to a positive and malleable cognitive state. Mindfulness is considered a process of shaping the innate quality of the mind in a systematic way. The practices of mindfulness are mainly through meditation. Within the context of mindfulness exercises, the inward gesture that invites and embodies the discipline is commonly referred to as the “practice” [3].

As Jon Kabat-Zinn has described mindfulness as a “consciousness discipline” heavily focused on systematic and scientific clinical intervention, it has sparked a conversation about what “practice” means in the context of mindfulness and meditation. His emphasis is that mindfulness should not be practised with attachment to results, despite the fact that “practice” is also perceived as a means to success by requiring discipline. In his estimation, both mindfulness and self-compassion practice should not be treated as therapeutic sessions that could heal or fix anything. Rather, they are opportunities to offer oneself an inner space to experience the existence of thoughts [4]. As such, mindfulness and compassion practices are aimed at facilitating self-acknowledgment of experiences, through patterns and behaviours.

In the view of Kabat-Zinn, mindfulness involves stepping back from situations and observing them from an alternative perspective, allowing us to make a more informed decision about how we react or respond. Understanding how we respond to situations, also allows us to see how we may be contributing to our distress and discomfort [4]. A mindfulness practice that is available to everyone can enhance different perspectives of people’s daily lives [4]. Making practice a ritual can make it more regularly integrated and deepen self-connection [5]. Despite the significant outcomes in reducing depression and stress [6], a systematic review of Mindfulness-Based School Intervention summarized that the mindfulness programmes in schools were mostly body scan meditation, mindful walking and listening, as well as adaptations of well-developed mindfulness interventions like Mindfulness-Based Stress Reduction [7]. However, establishing a daily dose of mindfulness practice is expected to cultivate a higher level of state mindfulness and positive emotion [8]. Apart from stillness meditation practice, this can include exercising (i.e., mindful walking), different forms of yoga, Tai Chi, and Qigong. Reviews have fully indicated the effect of yoga and other mind-and-body exercises in enhancing people’s mindfulness and other positive health outcomes [9,10,11]. Furthermore, it has been proposed [12] that mindfulness should be incorporated into everyday life with creativity that involves imagination, play, and openness. The creative and contemplative journal cultivated from mindfulness allows children and adolescents be fully engage in life experience directly, in other words, “being in the flow” [13] in their own lives, thus facilitating individuals’ self-awareness and mindful attention towards “ways of being” and “ways of living”, and further intrinsically connecting to oneself, to their home, and one another.

In the general school-learning perspective, mainstream subjects, such as Language, Mathematics, and Integrated Science, support students’ development of knowledge, skills, concepts, and values necessary to build an independent, civilized, and well-educated citizen [14]. The nature of home economics, however, is a field of study that focuses on the development of household management skills, including food and nutrition, clothing and textiles, and family and home management. It integrates people’s daily practical tools, determined by cultural and societal changes, such as globalization, localization, and technological advances, which are considered difficult to standardize and seen as having a lower economic value towards society [15]. However, research indicates that the central role and curriculum of home economics should aim at promoting sustainable well-being on a personal and global level, which includes health-related self-care techniques, self-perception, self-confidence, positive quality of life [16], and mental-health well-being [17,18]. Through the emphasis on practical skills related to food and textile production, as well as its emphasis on critical thinking and problem solving, a teacher survey has also revealed that home economics education provides a good understanding of household and society sustainable development [18]. Home economics education is expected to help people and families possess healthier and sustainable lifestyles by arming students with the knowledge and abilities they need to function in everyday life [19].

Food preparation and sewing are two examples of the practical skills home economics education generally teaches, indicating home economics education stands apart from other academic subjects due to its emphasis on practical skills and real-world applications. Systematic mindfulness training programmes or practices, like Mindfulness-Based Stress Reduction [20], Mindfulness-Based Cognitive Therapy [21] and Mindful Self-compassion [22], involve a session related to food, called mindful eating. During the mindful-eating practice, the person is required to eat slowly, mindfully aware of the smell, textures, colour, and flavours of the food, thus appreciating the given food. Sufficient research has indicated the effect of mindful eating on reducing binge eating and emotional eating, better weight management, and enhancement in both trait and state mindfulness [23,24,25,26]. Most importantly, mindful eating was to be effective in enhancing mindfulness and self-compassion, as well as the motive to have palatable foods among the student population [27]. It is because of this that mindful eating is considered as a tool to practise self-awareness and reduce the chance of having hindrances during practice; hence, mindful-eating practice is also considered as a practice that can be easily incorporated in a person’s daily life. Yet, other than the process of eating, the process of food preparation and cooking, which requires attention to every current moment, being aware of the change and texture of the raw food ingredients may also be considered as being mindful, and being in the process of food preparation is expected to enhance a person’s motives to savour.

Knitting shares several features with mindfulness, including an emphasis on the present, a repetitive and rhythmic action, and the capacity to enter a contemplative state. Knitting has a long history of thoughtfully benefiting societies as a traditional handicraft [28]. Knitting is seen to be a calming and meditative practice that enables people to make distinctive and individualized pieces. These pieces range from modest swatches to complex shawls and sweaters. Researchers and therapeutic professionals have recently started to investigate knitting’s potential as a mindfulness-based activity, offering a variety of psychological advantages for people seeking better self-care, relaxation, satisfaction [29], self-awareness, reducing stress, and even creating a state of “flow” [13,30].

Purpose of Research

Therefore, this paper aims to explore how self-care techniques like food preparation and knitting, as mindfulness exercises, have been incorporated into home economics education at the high school level to cultivate mindfulness and its benefits. Mindfulness has been studied and practised in clinical settings, but, as Kabat-Zinn [2,20] notes, it should also be embraced as a flexible, everyday practice that nourishes well-being, peace of mind, and happiness in daily life. As a result, the current paper aims to explore a theoretical and empirical perspective on this expanding field of study, including the possible relationship between knitting and mindfulness, as well as the relationship between food preparation, knitting, and mindfulness. The current paper is expected to explore the relationship between food preparation, knitting, and mindfulness through review, and to elucidate and uncover how food preparation and crafting could be embedded into daily mindfulness practices for both students and the general public. The overarching goal is also to cultivate a mindful embodiment of life skills that foster stress management, support emotional regulation, and enhance overall well-being, moving beyond clinical interventions or discipline-specific practices. In addition, the author will explore ways such practices could be promoted within home economics curricula to complement traditional mindfulness training modalities.

2. Method

2.1. Search and Screen Strategy

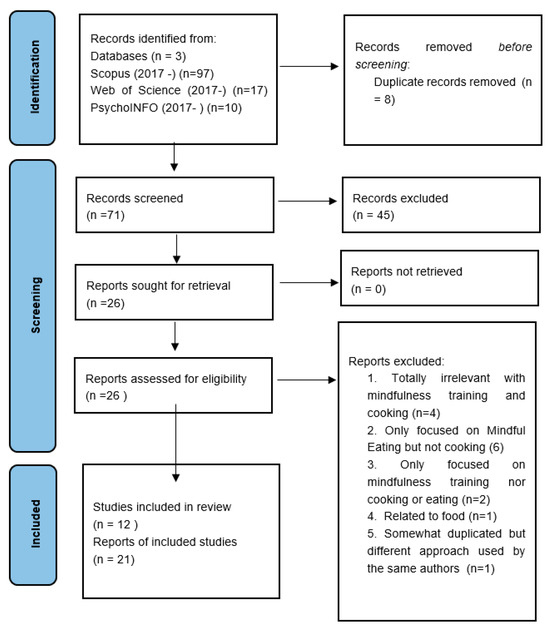

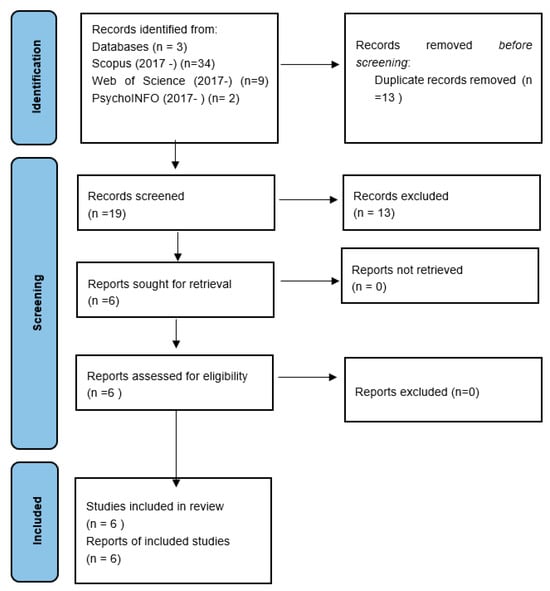

To illustrate the perspective of promoting home economics education with mindfulness, a review of the literature was implemented with a comprehensive paper extraction and screening process, as well as ensuring the quality of the selected research papers. The literature search covered research papers published within the most current trend of 5 years, starting from 2017 to 2022. The databases of Scopus (2017–Now), Web of Science (2017–Now), and PsychoINFO (2017–Now) were selected as they represent the most comprehensive sources for research in psychology and education. The article searches across the three databases were conducted in January 2023. The keywords and search terms were mindfulness and cooking, with the advanced search terms as “Mindfulness” AND “Cooking” OR “Cookery” OR “Meal Preparation”, as well as “Mindfulness” AND “Knitting” OR “Craftmanship”. All included papers had to be peer-reviewed, published in journals, including reviews but excluding conference proceedings, and written in English. Referencing from the PRISMA flow diagram (Figure 1 and Figure 2) [31], manual screening based on abstracts and titles was performed to exclude mindfulness-, crafting-, and cooking-irrelevant papers, as well as those that violate the eligibility criteria. Duplicated papers were also excluded from the screening process. Finally, all eligible papers were included in the full-text screening. Please refer to the Supplementary Materials File S1 for the PRISMA checklist for Scoping Review.

Figure 1.

PRISMA flow diagram (mindfulness and cooking).

Figure 2.

PRISMA flow diagram (mindfulness and knitting).

Various Joanna Briggs Institute’s (JBI) critical appraisal tools were used to appraise the quality of the retrieved research papers based on the study design required [32]. According to the study design, five different JBI critical appraisal tools were used to evaluate the methodological quality and risk of bias of the included studies. Qualitative studies were evaluated by the JBI Critical Appraisal for Qualitative Research, which involved the evaluation of congruity and representativity of the philosophical perspective, research objectives, and data. Qualitative research studies were involved in the current paper extraction to ensure triangulation and allow in-depth exploration, understanding, and interpretation of the mindfulness intervention content about cooking or knitting. Cross-sectional studies were evaluated by the JBI Critical Appraisal for Cross-sectional Study to investigate the validity and reliability of the measurement and analysis. The intervention studies were evaluated by the JBI Critical Appraisal for Randomized Controlled Trials and JBI Critical Appraisal for Quasi-experimental studies to indicate the procedures of conducting an intervention are achieved. JBI critical appraisal tools are standardized and validated tools to critically appraise diverse study designs, hence considered as representable and replicable. Studies with more than 70% “yes” in response to the tools’ questions indicated as a low risk of bias research study [33]. In addition to the author, a PhD student helper was involved in the appraisal process to avoid selection bias. Discrepancies arising during the screening and selection process were discussed and consensus was achieved with the author. Please refer to the Supplementary Materials (Tables S1 and S2) for the quality appraisal of the retrieved research papers.

2.2. Data Synthesis

The analysis of the retrieved research papers was described and utilized the relevant literature to reinforce the perspective of incorporating mindfulness into home economics education. Therefore, narrative synthesis [34] was used to uncover the connection between mindfulness and home economics education within the literature qualitatively. Narrative synthesis is able to gather sources with common concepts, ideas, and evidence to support the gap identification and proposed perspectives. Concepts, perspectives, evidence, and ideas related to home economics education and mindfulness in each of the retrieved papers were highlighted, then labelled and organized according to the identified categories [35]; for instance, intervention content, school-based programmes, home-economics-related activities, knitting and mindfulness/well-being, etc.

3. Results

3.1. Cooking

3.1.1. Cooking and Mindfulness Training

A total of 12 articles were retrieved and included in the review, with 6 qualitative research and 6 quantitative research papers. The 6 qualitative research papers involve programme protocol, commentary, and literature reviews. All the qualitative research papers showed 100% low risk of bias in the study quality appraisal.

Among the 12 articles, only 4 articles directly involved cooking as a mindfulness activity [36,37,38,39]. Unick et al. [39] is the only quantitative study on mindful cooking activities. However, it did not clearly state the blinding procedure of the randomized controlled trial, resulting in bias. The study met 75% of the critical appraisal criteria, indicating a low level of bias. It has conducted an intervention comparing the effect of yoga and cooking classes on weight changes, mindfulness, stress, emotions, and self-compassion. It is encouraging that, despite the yoga group having a higher score in mindfulness and self-compassion than that of the cooking group, there were no significant differences between the groups over time. It is worth noting that, among the participants with lower initial weight loss, which refers to having a low-level weight loss in the 3 months’ time, the participants in the cooking class showed a higher level of mindfulness and self-compassion level compared to that of the yoga class. It could be interpreted that, despite the cooking class having lower progress in reducing weight or in achieving health-related outcomes, it still showed an effect on enhancing mindfulness and self-compassion yet with less sustainability compared to that of doing yoga.

On the other hand, Eisenberg and Imamura [38] have discussed the importance of teaching kitchens in cultivating behaviour changes and mindfulness. It mentioned that the teaching kitchen curriculum raised by the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health and the Culinary Institute of America (i.e., healthy kitchens) emphasized that hands-on cooking classes should be developed with the elements of nutrition education, mindfulness training, and health coaching, which are considered self-care behaviours. It highlighted how cooking facilitates mindful diet, portion control, and achieving resilience. The process of creating spectacular dishes during cooking also facilitates the appreciation of food and mindfulness by feeling “liberated” and having more control over food.

Similarly, Dijker [37] aims to enhance people’s attitudes towards food through mindfulness, and cooking could be one way to do this. His research paper states that cooking should be treated as a craft which requires consciousness, objectivity, and attention towards the technical, moral, and aesthetic aspects of cooking a dish; together with the sensory and tasting experiences during cooking and eating, it activates the mindful care system of humans. With craftsmanship corresponding with care and love, it connects to authenticity, truth, purity, and kindness, which are important outcomes of equipping with mindfulness.

Finally, Burton and Smith’s intervention programme [36] is the only research paper that directly defined how mindfulness could be implemented in cooking. It stated that “In terms of cooking, mindfulness has numerous applications, from grocery shopping (attention to costs and nutritional quality of food being purchased) to food preparation (awareness of kitchen safety) and consumption (attention to serving sizes and satiety cues)”. Burton and Smith [36] have established an intervention programme named MEALS (Multidisciplinary Engagement and Learning/Mindful Eating and Active Living). It aims to provide cooking classes and provide students with opportunities to exercise mindfulness through awareness of different aspects of food and kitchen operations. For the study, students were required to mindfully select ingredients, conduct chopping and cutting, use cooking equipment, think of the likelihood of families being involved in their dietary routine, as well as conduct taste tests without being given the cooking recipe. After cooking, students were encouraged to present the food mindfully, as well as to smell and appreciate the appearance mindfully. It is noteworthy that MEALS was considered to be the first mindfulness-based cooking class, which was still under development.

3.1.2. Cooking and Mindfulness in Self-Care Programmes

Among the 12 articles, almost half (n = 5) [40,41,42,43,44] of the retrieved articles have illustrated cooking classes as part of a self-care or mindfulness programme; however, mindfulness was not clearly incorporated into the cooking classes. These studies embraced the idea of teaching kitchens [40,41,42]. These studies are also considered as having a low risk of bias that met 75–80% of the appraisal criteria. It is also expected that the novelty of cooking and mindfulness leads to difficulty in including comparisons with similar treated or other exposure of intervention. In these papers, cooking is presented as a self-management strategy which participants are required to learn in order to meet lifestyle needs. As part of the self-care training programme, cooking was considered one of the domains/themes, and mindfulness or mindful eating was considered another domain for participants to complete. This programme included other topics related to healthy lifestyle behaviours, such as exercise, yoga, healthy-eating education, goal setting for health behaviours, and information on stress management.

Similarly, the “Mission Thrive Summer” health intervention programme established by Pierce et al. [43] incorporated cooking and nutrition education with other mindfulness-based activities, like yoga, meditation, physical activity, and farming. As a result of engaging in the kitchen and overcoming challenges in the kitchen, the participants expressed a better sense of efficiency and awareness after the programme.

Thompson and his team [44] have also adopted a similar programme called the Meals, Mindfulness and Moving Forward (M3) lifestyle programme, which involves the same content but aims to achieve different psychological outcomes, such as self-efficacy and resilience through self-care activities. Cooking was coded to the same psychological themes as mindfulness, mainly self-efficacy and behavioural changes, even though mindfulness was coded to most psychological themes.

3.1.3. Other Reviews

Accordingly, the remaining three articles [45,46,47] simply indicate the elements of mindfulness through cooking. The studies revealed that cooking is considered part of eating competence by acknowledging that food has properties. This is carried out by developing an objective attitude towards food, and being aware of the serving of food, the quality, and the appearance of food. Cooking skills also facilitate food autonomy, food acceptance, and consciousness towards preparing and consuming meals, thus facilitating mindfulness [37,45]. Although de Quairoz et al.’s [45] studies did not focus on cooking as a mindfulness intervention, their illustrations were supported by Dijker [37], which is one of the retrieved studies mentioned above. It is not surprising that research pertaining to cooking and mindfulness has been based on mindful eating.

Compared to other mindful-eating-related research that has not touched on cooking, Méndez et al.’s [47] research paper states that food-based practices, like cooking and gardening, ought to be expanded within mindful eating and mindfulness practices. These food-related practices were suggested to be within the mechanism of mindful eating and mindful good parenting. This is because cooking, like love and affection, should be an integral part of families. Awareness of emotions revealing love and kindness is expected during the cooking process.

Finally, one intervention study used mindful eating and cooking training to evaluate reverse learning [46]; similarly, the concealment and blinding procedure were unclearly stated in the paper. However, other psychological measurements were involved and achieved 75% of the appraisal criteria, and therefore were included in the retrieval list. Surprisingly, the education cooking group resulted in a higher level of mindfulness than that of the mindful-eating group, even though no significant differences were found. Additionally, the education cooking group showed a greater difference in mindfulness and reduced emotional eating behaviour pre-post than that of the mindful-eating group.

3.2. Mindfulness and Knitting

A total of six articles were retrieved and included in the review, with three quantitative research studies, two reviews, and one book. The qualitative review and the only quasi-experimental studies achieved 100% of the appraisal criteria. Nonetheless, both qualitative cross-sectional studies showed an acceptable low risk of bias. However, limitations in identifying confounding factors and data analysis were noted.

Knitting and Well-Being

Research has begun to explore knitting’s psychological benefits, including its potential as a mindfulness practice. Corkhill and Riley [48] explored the varieties of ways knitting can contribute to people’s well-being, including enhancing mood through feelings of calmness, relaxation, and accomplishment. According to the survey, participants described knitting as “calming”, “restful”, or “spiritual”, while its “rhythm of repetition” was described as “hypnotic” and “calming”. They have also indicated the benefits of therapeutic knitting, which is claimed to create strong, resilient, and flexible minds during the knitting process. Also, knitting is seen to provide a variety of psychological advantages, whether it is performed alone or with others. These advantages include the ability to refocus attention in diversion situations, cultivating a sense of control, and a fulfilling activity that encourages relaxation and a sense of contribution. Knitters claim that abilities like persistence, perseverance, patience, and preparation may be applied to various facets of life, which can be beneficial for managing health and well-being. Knitters also learn that mistakes can be undone and that the end goal can be achieved by taking detours and learning from lessons along the way.

Considering the lack of exploration of “knitting” and mindfulness in particular, few articles on fabric crafting, well-being and mindfulness were reviewed. Kaimal and his team [49] revealed the percentage of US citizens participating in crafts and art activities. Among the activities, fabric crafting (i.e., weaving, crochet, needlepoint, knitting, and sewing) showed the highest percentage of participation, with people aged 18–34 ranking knitting second. With this foreseeable trend, Kaimal and his team [49] have shown that these crafts, including fabric crafting, can be used as healing agents in art therapy, which involves the discovery of a person’s symbolic self without emphasizing judgment, criticism, and logic, but rather being aesthetic and meditative. A study examined the effectiveness of a “Holistic Arts-based Group Program”, which emphasizes the importance of mindfulness in children through arts-based methods (such as crafting) and emphasizes the importance of paying attention to the moment, relaxation, compassion for oneself, and enhancing understanding of other people’s viewpoints, thus improving resilience and self-awareness [50]. Children aged 8–13 years old in the experimental groups found significantly higher levels of emotional resilience and positive changes in self-concept. The cross-sectional study also found that people who reported a high frequency of knitting experienced relaxation and feelings of stress relief during the process of knitting. It is also reported that regular knitters were associated with better cognitive functioning, perceived happiness, social interaction, and communication skills [51]. It is therefore an emerging topic to incorporate knitting as a mindfulness activity and to encourage it among children and teenagers through education.

4. Discussion

The term “home economics” traditionally refers to the management of the home and family, including cooking, sewing, and nutrition. As the knowledge of health and wellness has progressed, it has come to realize the significance of including mindfulness and self-care practices in our everyday routines [52]. The literature has well documented the benefits of deep breathing, yoga, and other mindfulness techniques for managing stress and anxiety, sharpening attention, and feeling better overall [9,11]. Similarly, creative pursuits like knitting, painting, cooking, or woodworking are a gratifying and calming method to unwind, which corresponds to the creative and contemplative mindfulness illustration of Siegel(s) [12]. Academic instruction has traditionally dominated high school curricula to better prepare students for post-secondary education and careers [53]. While intellectual abilities are essential for success in adulthood, it is also becoming increasingly clear that social and emotional abilities are just as significant. Despite this, home economics, a field of study that imparts fundamental living skills like cooking, cleaning, needlework, and budgeting, has steadily disappeared from many school curricula. Hence, this review aims to discover the potential of cooking and crafting to be incorporated into a mindfulness programme as a form of home economics education, without treating the mindful exercises as conscious deliberate practice.

For instance, knitting is a craft that may impart beneficial abilities like persistence, patience, and attention to detail, all of which are applicable to any life project or endeavour. Additionally, it acts as a type of self-care by calming down, alleviating tension, and encouraging relaxation [54]. Students would be able to gain useful skills and improve their ability to control their emotions by taking home economics and knitting classes in high school. This would also encourage students’ mindfulness and mental wellness, thus showing self-care and creative activities may be combined as a means to educate vital life skills and simultaneously promote well-being.

As a daily activity, cooking can be mindful at every moment. However, in terms of food-related mindfulness training, mindfulness eating is the only method that has been widely promoted in both general and clinical interventions [24]. The retrieved papers in the current review have captured a few studies that put forward the elements of mindfulness in cooking, beyond mindfulness eating. In fact, cooking-based mindfulness could be applied to different processes of cooking. A mindful selection of ingredients in the supermarket, sensing the colour of raw food ingredients, and measuring the required amount of ingredients through mindfully looking at a measuring cup can be a way to be mindful. The aim of mindful cooking is to observe and be aware of the stirring motion and the change of shape of the flour bun in the mixer while making bread, to feel the texture of the yeasting bread flour bun while stretching and folding, to hear and feel the sound when the dough is gently pressed down to release air bubbles, or even to grind beans with consciousness. Being mindful of the tangent plane of different foods and the sound of chopping are two examples of mindfulness. Moreover, the act of chopping minced pork can be construed as an act of fierce self-compassion, which is understood as an expression of anger and acceptance of emotion [55].

However, cooking-based mindfulness is constrained by the knowledge and techniques of the person. Participants are required to be equipped with sufficient application knowledge, such as proper use of a knife, cooking techniques, nutrition knowledge, and kitchen safety, in order to perform mindfulness. If not, hindrances might occur and affect the process of mindfulness practice. Hence, teaching kitchens or home economic education in compulsory schooling is highly encouraged, thus enhancing the cooking skills and ability of the general population, then facilitating cooking-based mindfulness as a daily practice rather than therapeutic intentions. Nevertheless, most of the retrieved papers did not treat cooking as a mindfulness practice, but rather categorized it as a self-care practice along with mindfulness, and resulted in similar psychological factors, like awareness, behavioural changes, and self-efficacy.

In general, despite there being no interventional studies examining the mindful effect of knitting, previous surveys revealed the calmness and sense of soothing brought by the process of knitting [28,54]. The previous studies have focused on the effect of cooking on cultivating healthy-eating behaviours and nutrition literacy [56], at the same time, the retrieved studies have embraced the mindful process of cooking to a certain extent, thus cultivating cooking-based mindfulness. Moreover, the art of cooking involves human care, love, and attention throughout the process of cooking, such as food preparation, presentation of food, and using cooking equipment, which could be seen as being mindful.

4.1. Potential for Home Economics to Incorporate Mindfulness Practices

In light of this, home economics education is believed to provide students with valuable tools for managing their health through mindfulness. A nutrition class, for instance, might include mindfulness exercises before preparing a healthy meal. A knitting class could discuss the benefits of crafting for stress relief and self-care. As a way of learning meditation, students can learn how to focus on each stitch and let go of distractions by letting go of the urge to knit. A particular benefit of this would be to students who are predisposed to anxiety or other forms of stress, such as those experiencing depression. Craftsmanship is considered to be an important prerequisite of sustainability and a way to connect with nature [57]—one that is closely linked with the process of being mindful—including focusing on feeling, sensing, non-judgmental noticing, self-reflection, and other aspects of self-awareness [57,58].

In the paper “Mindfulness In, As and Of Education: Three Roles of Mindfulness in Education”, it has been [59] indicated that “mindfulness in education” contributes to teachers’ and students’ cognitive and emotional capabilities, as well as emphasizing self-knowledge and “divorcing technique from those accounts’ underlying values” [60]. Hence, a holistic approach should be one of the most effective means to apply mindfulness to their lives. It cultivates a child’s character, compassion, values, knowledge, and social engagement [58,59,61].

Nevertheless, challenges in upholding the importance and conception of home economics education should be addressed. Despite the sustainable education required by the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development [62], I observed there is still a proportion of schools lacking resources in supporting equipment for home economics education, not limited to crafts but also cooking, such as a sewing machine or a cookery room with a supportable and affordable electricity system. Home economics education was the first introduction to subjects in the early days of the 20th century. However, only 25% of students worldwide have enrolled in home economics education classes in the last 20 years [63]. This lack of student enrolment has affected the development of professional home economics teachers. Hence, the skills level and experiences of teachers might not be sufficient to deliver classes in an all-round manner. Most importantly, home economics has been associated with gender stereotypes [64], which may discourage some male students from participating or cause them to view it as an un-masculine subject. This would also reduce students’ interest, especially in mixed-gender schools. It is important to note that, by appreciating the value of home economics, students are provided with the necessary skills to flourish as adults and advance their general well-being. As a result, it is suggested educators integrate well-being education into home economics lessons that promote mindful practices of life skills, like cooking and sewing, at the same time emphasizing the value of life skills/home economics education for all students regardless of gender. Further research should explore approaches that help overcome these challenges and actively work to combat gender stereotypes and emphasize the importance of home economics education among all learners.

4.2. Limitations

Firstly, the purpose of this research paper is to explore whether there is existing literature indicating the association between mindfulness, cooking (food preparation), and knitting (crafting). In fact, there were a limited number of studies, yet at the same time, the author would like to review these limited studies comprehensively; hence, this paper falls between the form of a scoping review and a perspective paper. As a result, more experiments and cross-sectional research studies should be conducted in the future to investigate the direct effect of food preparation and knitting on mindfulness and well-being. Secondly, food preparation and knitting are not considered as the only content in home economics lessons, they also involve household and family management; therefore, more investigation and discussion on household management and mindfulness is suggested. Lastly, additional research is required to determine how these mindful activities, as part of a comprehensive home economics course, can best be added to the curriculum to support student self-care. For instance, teacher training on mindfulness should be provided; teachers are required to understand the philosophy of mindfulness in order to teach and incorporate mindfulness practically in food preparation and crafting during lessons. Moreover, teachers should be encouraged to arrange specific class periods for mindfulness practice or topics in their lesson plan, such as designating specific food preparation skills and guiding the skills with mindfulness-based guidance wordings. For example, teaching could guide students’ cutting vegetable practice with the following sentences, “Now as you prepare to slice the carrot, take a moment to become fully present. Be aware of how the knife feels in your hand. Notice the texture and color of the carrot on the chopping board. Slice slowly and mindfully, paying attention to both the thickness of each slice and the crisp sound it makes. As you chop, focus only on the sensory experiences of this moment—what you see, feel and hear. Focus on the current moment”.

5. Conclusions

To the author’s best knowledge, this is the only research paper that aimed to illustrate and promote the linkage between mindfulness and home economics education. Hence, a comprehensive data synthesis method, such as thematic analysis, could not be adopted due to the lack of research papers with consistent research questions specific to mindfulness and home economics education. In conclusion, the review was able to identify scattered evidence regarding the connection between home economics education and mindfulness, through eating, cooking, and crafting. In support of positive mental health, the importance of mindfulness has been identified, as has the ability of knitting and food preparation to promote mindfulness.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/youth3040083/s1, Table S1: Critical Appraisal of the Retrieved Papers. (Mindfulness and Cooking); Table S2: Critical Appraisal of the Retrieved Papers. (Mindfulness and Knitting); File S1: Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-Analyses extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR) Checklist.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

There is no new data generated.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

References

- McCaw, C.T. Mindfulness ‘Thick’ and ‘Thin’—A Critical Review of the Uses of Mindfulness in Education. Oxf. Rev. Educ. 2020, 46, 257–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kabat-Zinn, J. Mindfulness. Mindfulness 2015, 6, 1481–1483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Depraz, N.; Varela, F.J.; Vermersch, P. The Gesture of Awareness. In Investigating Phenomenal Consciousness; John Benjamins Publishing Company: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2000; pp. 121–136. [Google Scholar]

- Kabat-Zinn, J. The Liberative Potential of Mindfulness. Mindfulness 2021, 12, 1555–1563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neenan, K. Being Human: Cultivating Mindfulness and Compassion for Daily Living. In Spirituality in Healthcare: Perspectives for Innovative Practice; Springer Nature: Berlin, Germany, 2019; pp. 211–223. [Google Scholar]

- Dunning, D.L.; Griffiths, K.; Kuyken, W.; Crane, C.; Foulkes, L.; Parker, J.; Dalgleish, T. Research Review: The Effects of Mindfulness-based Interventions on Cognition and Mental Health in Children and Adolescents—A Meta-analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials. J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry 2019, 60, 244–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKeering, P.; Hwang, Y.-S. A Systematic Review of Mindfulness-Based School Interventions with Early Adolescents. Mindfulness 2019, 10, 593–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levi, K.; Shoham, A.; Amir, I.; Bernstein, A. The Daily Dose-Response Hypothesis of Mindfulness Meditation Practice: An Experience Sampling Study. Psychosom. Med. 2021, 83, 624–630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, J.; McLean, L.; Korner, A.; Stratton, E.; Glozier, N. Mindfulness and Yoga for Psychological Trauma: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J. Trauma Dissociation 2020, 21, 536–573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waechter, R.L.; Wekerle, C. Promoting Resilience among Maltreated Youth Using Meditation, Yoga, Tai Chi and Qigong: A Scoping Review of the Literature. Child Adolesc. Soc. Work J. 2015, 32, 17–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, L.; Sasaki, J.E.; Wei, G.-X.; Huang, T.; Yeung, A.S.; Neto, O.B.; Chen, K.W.; Hui, S.S. Effects of Mind–Body Exercises (Tai Chi/Yoga) on Heart Rate Variability Parameters and Perceived Stress: A Systematic Review with Meta-Analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials. J. Clin. Med. 2018, 7, 404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Siegel, D.J.; Siegel, M.W. Thriving with Uncertainty: Opening the Mind and Cultivating Inner Well-Being Through Contemplative and Creative Mindfulness. In Wiley Blackwell Handbook of Mindfulness; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2014; p. 19. [Google Scholar]

- Csikszentmihalyi, M.; Abuhamdeh, S.; Nakamura, J. Flow. In Flow and the Foundations of Positive Psychology the Collected Works of Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2014; pp. 227–238. [Google Scholar]

- OECD. Student Learning: Attitudes, Engagement and Strategies. In Learning for Tomorrow’s World—First Results from PISA 2003; OECD: Paris, France, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Taar, J.; Palojoki, P. Applying Interthinking for Learning 21st-Century Skills in Home Economics Education. Learn. Cult. Soc. Interact. 2022, 33, 100615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erjavšek, M. Modern Aspects of Home Economics Education and Slovenia. Cent. Educ. Policy Stud. J. 2021, 11, 33–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dewhurst, Y.; Pendergast, D. Teacher Perceptions of the Contribution of Home Economics to Sustainable Development Education: A Cross-Cultural View. Int. J. Consum. Stud. 2011, 35, 569–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haapala, I.; Biggs, S.; Cederberg, R.; Kosonen, A.-L. Home Economics Teachers’ Intentions and Engagement in Teaching Sustainable Development. Scand. J. Educ. Res. 2014, 58, 41–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maguire, H.; McCloat, A. Home Economics Education: Preparation for a Sustainable and Healthy Future. In Rethinking Education on a Changing Planet; Island Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2017; pp. 165–178. [Google Scholar]

- Kabat-Zinn, J. Mindfulness-Based Stress Reduction (MBSR). Constr. Hum. Sci. 2003, 8, 73. [Google Scholar]

- Querstret, D.; Morison, L.; Dickinson, S.; Cropley, M.; John, M. Mindfulness-Based Stress Reduction and Mindfulness-Based Cognitive Therapy for Psychological Health and Well-Being in Nonclinical Samples: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Int. J. Stress. Manag. 2020, 27, 394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neff, K. Self-Compassion: The Proven Power of Being Kind to Yourself; Hachette: London, UK, 2011; ISBN 1-4447-3818-6. [Google Scholar]

- Bush, H.E.; Rossy, L.; Mintz, L.B.; Schopp, L. Eat for Life: A Work Site Feasibility Study of a Novel Mindfulness-Based Intuitive Eating Intervention. Am. J. Health Promot. 2014, 28, 380–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grider, H.S.; Douglas, S.M.; Raynor, H.A. The Influence of Mindful Eating and/or Intuitive Eating Approaches on Dietary Intake: A Systematic Review. J. Acad. Nutr. Diet. 2021, 121, 709–727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jordan, J.; McIntosh, V.V.; Carter, J.D.; Rowe, S.; Taylor, K.; Frampton, C.M.; McKenzie, J.M.; Latner, J.; Joyce, P.R. Bulimia Nervosa-nonpurging Subtype: Closer to the Bulimia Nervosa-purging Subtype or to Binge Eating Disorder? Int. J. Eat. Disord. 2014, 47, 231–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warren, J.M.; Smith, N.; Ashwell, M. A Structured Literature Review on the Role of Mindfulness, Mindful Eating and Intuitive Eating in Changing Eating Behaviours: Effectiveness and Associated Potential Mechanisms. Nutr. Res. Rev. 2017, 30, 272–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keyte, R.; Egan, H.; Mantzios, M. How Does Mindful Eating without Non-Judgement, Mindfulness and Self-Compassion Relate to Motivations to Eat Palatable Foods in a Student Population? Nutr. Health 2020, 26, 27–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fisk, A. “Stitch for Stitch, You Are Remembering”: Knitting and Crochet as Material Memorialization. Mater. Relig. 2019, 15, 553–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, M.Y. An Exploratory Study on Finger Knitting-Facilitated Therapy. Ph.D. Thesis, Hong Kong Polytechnic University, Kowloon, Hong Kong, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Utsch, H. Knitting and Stress Reduction. Ph.D. Thesis, Antioch University New England, Keene, NH, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E. The PRISMA 2020 Statement: An Updated Guideline for Reporting Systematic Reviews. Int. J. Surg. 2021, 88, 105906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The Joanna Briggs Institute. Joanna Briggs Institute Reviewers’ Manual; 2014 ed.; The Joanna Briggs Institute: Adelaide, SA, Australia, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Jørgensen, L.; Paludan-Müller, A.S.; Laursen, D.R.T.; Savović, J.; Boutron, I.; Sterne, J.A.C.; Higgins, J.P.T.; Hróbjartsson, A. Evaluation of the Cochrane Tool for Assessing Risk of Bias in Randomized Clinical Trials: Overview of Published Comments and Analysis of User Practice in Cochrane and Non-Cochrane Reviews. Syst. Rev. 2016, 5, 80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Popay, J.; Roberts, H.; Sowden, A.; Petticrew, M.; Arai, L.; Rodgers, M.; Britten, N.; Roen, K.; Duffy, S. Guidance on the Conduct of Narrative Synthesis in Systematic Reviews. A Product from the ESRC Methods Programme; Institute for Health Research: London, UK, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Sharp, N.L.; Bye, R.A.; Cusick, A. Narrative Analysis. In Handbook of Research Methods in Health Social Sciences; Springer: Singapore, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Burton, E.T.; Smith, W.A. Mindful Eating and Active Living: Development and Implementation of a Multidisciplinary Pediatric Weight Management Intervention. Nutrients 2020, 12, 1425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dijker, A.J. Moderate Eating with Pleasure and without Effort: Toward Understanding the Underlying Psychological Mechanisms. Health Psychol. Open 2019, 6, 2055102919889883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eisenberg, D.M.; Imamura, B. Anthony Teaching Kitchens in the Learning and Work Environments: The Future Is Now. Glob. Adv. Health Med. 2020, 9, 2164956120962442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Unick, J.L.; Dunsiger, S.I.; Bock, B.C.; Sherman, S.A.; Braun, T.D.; Wing, R.R. A Preliminary Investigation of Yoga as an Intervention Approach for Improving Long-Term Weight Loss: A Randomized Trial. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0263405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eisenberg, D.M.; Righter, A.C.; Matthews, B.; Zhang, W.; Willett, W.C.; Massa, J. Feasibility Pilot Study of a Teaching Kitchen and Self-Care Curriculum in a Workplace Setting. Am. J. Lifestyle Med. 2019, 13, 319–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gardiner, P.; McGonigal, L.; Villa, A.; Kovell, L.C.; Rohela, P.; Cauley, A.; Rinker, D.; Olendzki, B. Our Whole Lives for Hypertension and Cardiac Risk Factors—Combining a Teaching Kitchen Group Visit with a Web-Based Platform: Feasibility Trial. JMIR Form. Res. 2022, 6, e29227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kakareka, R.; Stone, T.A.; Plsek, P.; Imamura, A.; Hwang, E. Fresh and Savory: Integrating Teaching Kitchens with Shared Medical Appointments. J. Altern. Complement. Med. 2019, 25, 709–718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pierce, B.; Bowden, B.; McCullagh, M.; Diehl, A.; Chissell, Z.; Rodriguez, R.; Berman, B.M. A Summer Health Program for African-American High School Students in Baltimore, Maryland: Community Partnership for Integrative Health. Explore 2017, 13, 186–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thompson, A.; Senders, A.; Seibel, C.; Usher, C.; Borgatti, A.; Bodden, K.; Calabrese, C.; Hagen, K.; David, J.; Bourdette, D. Qualitative Analysis of the Meals, Mindfulness, & Moving Forward (M3) Lifestyle Programme: Cultivating a ‘Safe Space’to Start on a ‘New Path’for Youth with Early Episode Psychosis. Early Interv. Psychiatry 2021, 15, 87–95. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- de Queiroz, F.L.N.; Raposo, A.; Han, H.; Nader, M.; Ariza-Montes, A.; Zandonadi, R.P. Eating Competence, Food Consumption and Health Outcomes: An Overview. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 4484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Janssen, L.K.; Duif, I.; Van Loon, I.; De Vries, J.H.; Speckens, A.E.; Cools, R.; Aarts, E. Greater Mindful Eating Practice Is Associated with Better Reversal Learning. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 5702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Méndez, R.; Goto, K.; Song, C.; Giampaoli, J.; Karnik, G.; Wylie, A. Cultural Influence on Mindful Eating: Traditions and Values as Experienced by Mexican-American and Non-Hispanic White Parents of Elementary-School Children. Glob. Health Promot. 2020, 27, 6–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corkhill, B.; Hemmings, J.; Maddock, A.; Riley, J. Knitting and Well-Being. TEXTILE 2014, 12, 34–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaimal, G.; Gonzaga, A.M.L.; Schwachter, V. Crafting, Health and Wellbeing: Findings from the Survey of Public Participation in the Arts and Considerations for Art Therapists. Arts Health Int. J. Res. Policy Pract. 2017, 9, 81–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coholic, D.; Eys, M.; Lougheed, S. Investigating the Effectiveness of an Arts-Based and Mindfulness-Based Group Program for the Improvement of Resilience in Children in Need. J. Child Fam. Stud. 2012, 21, 833–844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riley, J.; Corkhill, B.; Morris, C. The Benefits of Knitting for Personal and Social Wellbeing in Adulthood: Findings from an International Survey. Br. J. Occup. Ther. 2013, 76, 50–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cook-Cottone, C.P.; Guyker, W.M. The Development and Validation of the Mindful Self-Care Scale (MSCS): An Assessment of Practices That Support Positive Embodiment. Mindfulness 2018, 9, 161–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aliaga, O.A.; Kotamraju, P.; Stone, J.R.I. Understanding Participation in Secondary Career and Technical Education in the 21st Century: Implications for Policy and Practice. High. Sch. J. 2014, 97, 128–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pöllänen, S.H.; Weissmann-Hanski, M.K. Hand-Made Well-Being: Textile Crafts as a Source of Eudaimonic Well-Being. J. Leis. Res. 2020, 51, 348–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neff, K. Fierce Self-Compassion: How Women Can Harness Kindness to Speak up, Claim Their Power, and Thrive; Penguin: London, UK, 2021; ISBN 0-241-44867-0. [Google Scholar]

- Vettori, V.; Lorini, C.; Milani, C.; Bonaccorsi, G. Towards the Implementation of a Conceptual Framework of Food and Nutrition Literacy: Providing Healthy Eating for the Population. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health 2019, 16, 5041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hofsess, B.A. Renewing a Craftsmanship of Attention with the World. Stud. Art. Educ. 2021, 62, 184–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bates, J.K. Uniting Body, Mind, and Spirit through Art Education: A Guide for Holistic Teaching in Middle and High School; ERIC: Reston, VA, USA, 2020; ISBN 1-890160-72-5. [Google Scholar]

- Ergas, O. Mindfulness in, as and of Education: Three Roles of Mindfulness in Education. J. Philos. Educ. 2019, 53, 340–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hyland, T. The Limits of Mindfulness: Emerging Issues for Education. Br. J. Educ. Stud. 2016, 64, 97–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graham, M.A.; Lewis, R. Mindfulness as Art Education, Self-Inquiry, and Artmaking. Stud. Art. Educ. 2023, 64, 75–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OECD. The Future of Education and Skills: Education 2030 (Position Paper) 1; OECD: Paris, France, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Home Economics Teacher Certification. 2023. Available online: https://teaching-certification.com/home-economics-teacher-certification/#link2 (accessed on 5 September 2023).

- Kim, E.J.; Lee, Y.-J.; Kim, J. A Study of the Gender-Biased Attitudes of Korean Middle School Students toward Home Economics as a Subject: Implementing the Implicit Association Test. Hum. Ecol. Res. 2019, 57, 459–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).