Foundations and Clinical Applications of Fractal Dimension in Neuroscience: Concepts and Perspectives

Abstract

1. Introduction

- (1)

- How do different FD estimation methods and methodological choices influence the interpretation and comparability of FD across neuroimaging and neurophysiological modalities?

- (2)

- What consistent patterns of FD alteration emerge across neurodevelopmental, neurodegenerative, and consciousness-related conditions, and how do these relate to underlying biological mechanisms?

- (3)

- To what extent can FD serve as a unifying multiscale biomarker bridging empirical measurements with theoretical models of brain dynamics and information integration?

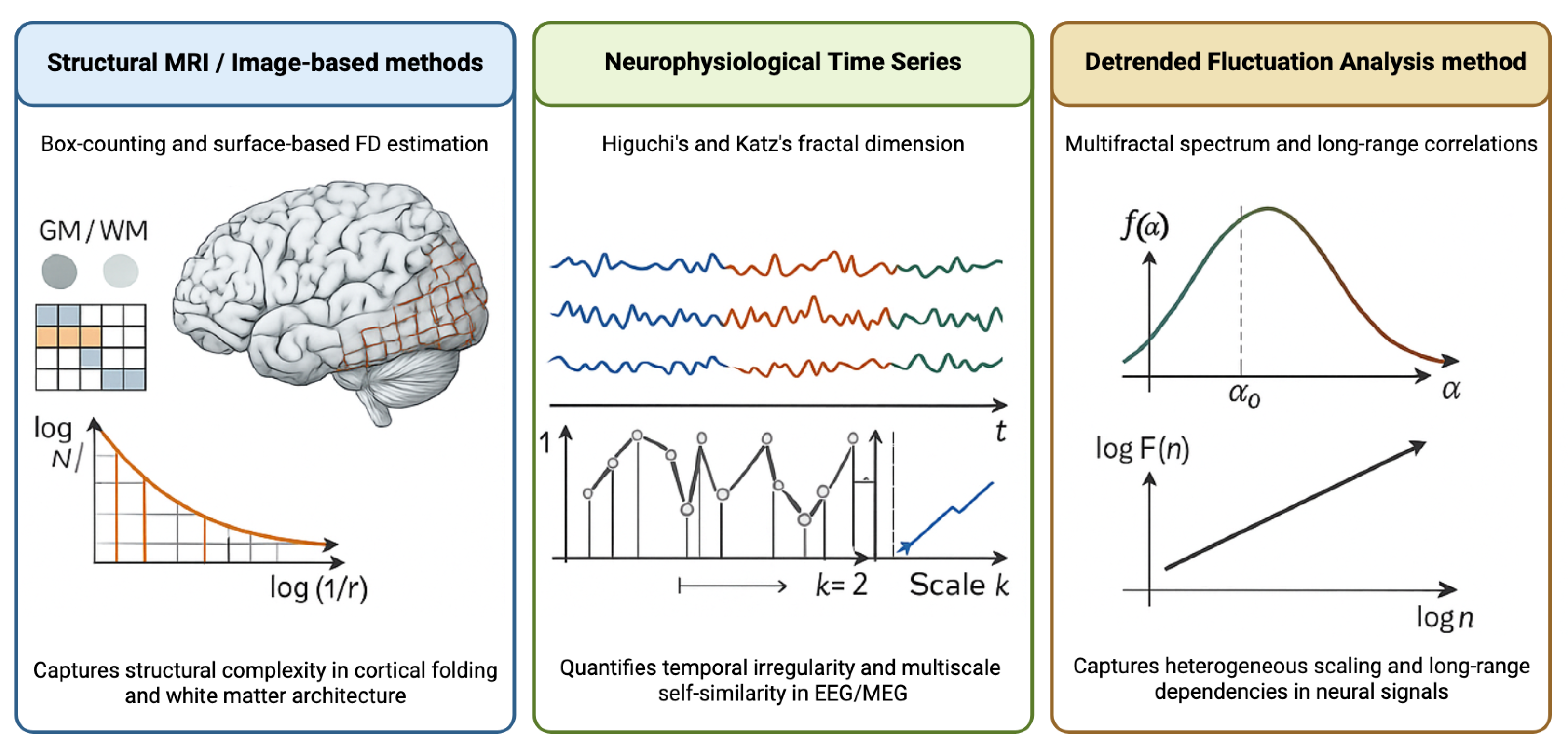

2. Methodological Foundations

3. Structural Neuroimaging Applications

4. Neurodegenerative Disorders

5. Neurophysiology and Consciousness

6. Integration with Computational Neuroscience and Network Analysis

7. Limitations and Future Directions

8. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| DFA | Detrended fluctuation analysis |

| DTI | Diffusion tensor imaging |

| EEG | Electroencephalography |

| FA | Fractional anisotropy |

| FD | Fractal dimension |

| FDI | Fractal dimension index |

| fMRI | Functional magnetic resonance imaging |

| GPU | Graphics processing unit |

| HFD | Higuchi’s fractal dimension |

| IUGR | Intrauterine growth restriction |

| MD | Mean diffusivity |

| MEG | Magnetoencephalography |

| MRI | Magnetic resonance imaging |

| MS | Multiple sclerosis |

| NAWM | Normal-appearing white matter |

| PET | Positron emission tomography |

Appendix A. Best Practices for FD Estimation in Neuroimaging

- -

- Image preprocessing: Apply consistent intensity normalization and bias field correction to minimize signal inhomogeneity artifacts; perform skull stripping using validated algorithms with manual quality control verification; ensure standardized spatial normalization when comparing across subjects while recognizing that registration quality impacts FD estimates.

- -

- Segmentation and tissue Selection: Use automated segmentation tools with demonstrated reliability for tissue classification; maintain consistency in tissue compartment definitions across all analyses within a study; consider separate FD computation for gray matter, white matter, and white matter boundaries as these compartments exhibit distinct complexity patterns and pathological sensitivities.

- -

- Scale range selection: Implement automated scale optimization procedures that determine appropriate box size ranges for individual images rather than applying fixed ranges across all data; validate selected scales against theoretical expectations and mathematical phantoms; document and report the scale ranges used to enable cross-study comparisons and methodological transparency.

- -

- Binarization and skeletonization: Apply standardized thresholding procedures with explicit documentation of intensity selection criteria; recognize that skeletonization may enhance sensitivity to specific structural features but also introduces additional processing steps that require validation; compare results with and without skeletonization to assess robustness.

- -

- Quality control: Visually inspect all segmentation outputs and preprocessing results to identify failures or artifacts; exclude scans with excessive motion, insufficient tissue contrast, or processing errors; document exclusion criteria prospectively; perform test–retest reliability assessments within your specific acquisition protocol and processing pipeline to establish measurement stability for your implementation.

- -

- Computational implementation: Utilize GPU acceleration for large-scale studies to ensure practical feasibility; validate computational implementations against datasets with known theoretical FD values; ensure numerical stability across the full range of box sizes; maintain version control for analysis software and document all parameter settings to support reproducibility.

Appendix B. Key Open Questions and Promising Research Directions

- -

- How can multifractal analysis be optimized to capture regional heterogeneity in complexity patterns while maintaining computational stability and biological interpretability?

- -

- What are the optimal spatial resolution requirements and signal-to-noise thresholds for reliable FD estimation across different imaging modalities and brain structures?

- -

- Can machine learning approaches automatically optimize scale range selection and preprocessing parameters for individual datasets to minimize estimation bias?

- -

- How can computational efficiency be further improved to enable real-time FD calculation for clinical decision support applications?

- -

- What are the minimal clinically important differences in FD values that correspond to meaningful functional or prognostic distinctions across neurological populations?

- -

- Can FD thresholds be established for risk stratification and early detection screening programs in presymptomatic at-risk populations?

- -

- How do longitudinal FD trajectories relate to treatment response, disease progression rates, and long-term functional outcomes in prospective clinical trials?

- -

- What is the added value of FD measures beyond conventional structural and functional biomarkers in multivariate diagnostic and prognostic models?

- -

- What are the precise mathematical relationships between FD measured from neuroimaging data and the FD of underlying neural network attractors predicted by dynamical systems theory?

- -

- How do cellular-level architectural principles (dendritic branching patterns, synaptic organization, glial morphology) scale up to determine macroscopic FD values observable in neuroimaging?

- -

- Can theoretical frameworks linking complexity, information integration, and consciousness be empirically tested using FD as a quantitative proxy for integrated information?

- -

- What evolutionary and developmental pressures shape the fractal properties of brain architecture, and how do these principles inform our understanding of optimal versus pathological complexity levels?

References

- Mandelbrot, B.B. Fractals: Form, Chance, and Dimension; W. H. Freeman and Company: San Francisco, CA, USA, 1977. [Google Scholar]

- Mandelbrot, B.B. The Fractal Geometry of Nature; W. H. Freeman and Company: New York, NY, USA, 1983. [Google Scholar]

- Falconer, K. Fractal Geometry: Mathematical Foundations and Applications, 3rd ed.; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Di Ieva, A.; Esteban, F.J.; Grizzi, F.; Klonowski, W.; Martín-Landrove, M. Fractals in the neurosciences, Part II: Clinical applications and future perspectives. Neuroscientist 2015, 21, 30–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Losa, G.A.; Merlini, A.; Nonnenmacher, T.F.; Weibel, E.R. Fractals in Biology and Medicine; Birkhäuser Verlag: Basel, Switzerland, 2005; Volume 4. [Google Scholar]

- Di Ieva, A. The Fractal Geometry of the Brain; Springer Nature: Cham, Switzerland, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Porcaro, C.; Diccioti, S.; Madan, C.R.; Marzi, C. Editorial: Methods and application in fractal analysis of neuroimaging data. Front. Hum. Neurosci. 2024, 18, 1453284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krohn, S.; Froeling, M.; Leemans, A.; Ostwald, D.; Villoslada, P.; Finke, C.; Esteban, F.J. Evaluation of the 3D fractal dimension as a marker of structural brain complexity in multiple-acquisition MRI. Hum. Brain Mapp. 2019, 40, 3299–3320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marzi, C.; Giannelli, M.; Tessa, C.; Mascalchi, M.; Diciotti, S. Toward a more reliable characterization of fractal properties of the cerebral cortex of healthy subjects during the lifespan. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 16957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grosu, G.F.; Hopp, A.V.; Moca, V.V.; Bârzan, H.; Ciuparu, A.; Ercsey-Ravasz, M.; Winkel, M.; Linde, H.; Mureșan, R.C. The fractal brain: Scale-invariance in structure and dynamics. Cereb. Cortex 2023, 33, 4574–4605, Erratum in Cereb. Cortex 2023, 33, 10475. https://doi.org/10.1093/cercor/bhad335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esteban, F.J.; Sepulcre, J.; de Mendizábal, N.V.; Goñi, J.; Navas, J.; de Miras, J.R.; Bejarano, B.; Masdeu, J.C.; Villoslada, P. Fractal dimension and white matter changes in multiple sclerosis. NeuroImage 2007, 36, 543–549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruiz de Miras, J.; Navas, J.; Villoslada, P.; Esteban, F.J. UJA-3DFD: A program to compute the 3D fractal dimension from MRI data. Comput. Methods Programs Biomed. 2011, 104, 452–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Higuchi, T. Approach to an irregular time series on the basis of the fractal theory. Physica D 1988, 31, 277–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruiz de Miras, J.; Soler, F.; Iglesias-Parro, S.; Ibáñez-Molina, A.J.; Casali, A.G.; Laureys, S.; Massimini, M.; Esteban, F.J.; Navas, J.; Langa, J.A. Fractal dimension analysis of states of consciousness and unconsciousness using transcranial magnetic stimulation. Comput. Methods Programs Biomed. 2019, 175, 129–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hardstone, R.; Poil, S.S.; Schumacher, J.; Mühlen, C.; Sip, R.; Douw, L.; van Dijk, B.W.; Vander Leeuw, S.E.; Linkenkaer-Hansen, K. Detrended Fluctuation Analysis: A Scale-Free View on Neuronal Oscillations. Front. Physiol. 2012, 3, 450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Díaz Beltrán, L.; Madan, C.R.; Finke, C.; Krohn, S.; Di Ieva, A.; Esteban, F.J. Fractal Dimension Analysis in Neurological Disorders: An Overview. Adv. Neurobiol. 2024, 36, 313–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, H.; Liu, T.; Jiang, J.; Cheng, J.; Liu, Y.; Li, D.; Dong, C.; Niu, H.; Li, S.; Zhang, J.; et al. Differential longitudinal changes in structural complexity and volumetric measures in community-dwelling older individuals. Neurobiol. Aging 2020, 91, 26–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ziukelis, E.T.; Mak, E.; Dounavi, M.E.; Su, L.; O’Brien, J.T. Fractal dimension of the brain in neurodegenerative disease and dementia: A systematic review. Ageing Res. Rev. 2022, 79, 101651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Madan, C.R.; Kensinger, E.A. Test-retest reliability of brain morphology estimates. Brain Inform. 2017, 4, 107–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makropoulos, A.; Counsell, S.J.; Rueckert, D. A review on automatic fetal and neonatal brain MRI segmentation. NeuroImage 2018, 170, 231–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiménez, J.; López, A.M.; Cruz, J.; Esteban, F.J.; Navas, J.; Villoslada, P.; Ruiz de Miras, J. A Web platform for the interactive visualization and analysis of the 3D fractal dimension of MRI data. J. Biomed. Inform. 2014, 51, 176–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nazlee, N.; Waiter, G.D.; Sandu, A.L. Age-associated sex and asymmetry differentiation in hemispheric and lobar cortical ribbon complexity across adulthood: A UK Biobank imaging study. Hum. Brain Mapp. 2023, 44, 49–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Zuo, Y.; Kang, S.; Pan, L.; Jiang, S.; Yan, A.; Li, L. Using fractal dimension analysis to assess the effects of normal aging and sex on subregional cortex alterations across the lifespan from a Chinese dataset. Cereb. Cortex 2023, 33, 5289–5296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Dean, D.; Liu, J.Z.; Sahgal, V.; Wang, X.; Yue, G.H. Quantifying degeneration of white matter in normal aging using fractal dimension. Neurobiol. Aging 2007, 28, 1543–1555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madan, C.R. Age-related decrements in cortical gyrification: Evidence from an accelerated longitudinal dataset. Eur. J. Neurosci. 2021, 53, 1661–1671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esteban, F.J.; Padilla, N.; Sanz-Cortés, M.; de Miras, J.R.; Bargalló, N.; Villoslada, P.; Gratacós, E. Fractal-dimension analysis detects cerebral changes in preterm infants with and without intrauterine growth restriction. NeuroImage 2010, 53, 1225–1232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hedderich, D.M.; Bäuml, J.G.; Menegaux, A.; Avram, M.; Daamen, M.; Zimmer, C.; Bartmann, P.; Scheef, L.; Boecker, H.; Wolke, D.; et al. An analysis of MRI derived cortical complexity in premature-born adults: Regional patterns, risk factors, and potential significance. NeuroImage 2020, 208, 116438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reishofer, G.; Studencnik, F.; Koschutnig, K.; Deutschmann, H.; Ahammer, H.; Wood, G. Age is reflected in the Fractal Dimensionality of MRI Diffusion Based Tractography. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 5431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Squarcina, L.; Lucini Paioni, S.; Bellani, M.; Rossetti, M.G.; Houenou, J.; Polosan, M.; Phillips, M.L.; Wessa, M.; Brambilla, P. White matter integrity in bipolar disorder investigated with diffusion tensor magnetic resonance imaging and fractal geometry. J. Affect. Disord. 2024, 345, 200–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porcaro, C.; Di Renzo, A.; Tinelli, E.; Di Lorenzo, G.; Parisi, V.; Caramia, F.; Fiorelli, M.; Di Piero, V.; Pierelli, F.; Coppola, G. Haemodynamic activity characterization of resting state networks by fractal analysis and thalamocortical morphofunctional integrity in chronic migraine. J. Headache Pain 2020, 21, 112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esteban, F.J.; Sepulcre, J.; de Miras, J.R.; Navas, J.; de Mendizábal, N.V.; Goñi, J.; Quesada, J.M.; Bejarano, B.; Villoslada, P. Fractal dimension analysis of grey matter in multiple sclerosis. J. Neurol. Sci. 2009, 282, 67–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- King, R.D.; Brown, B.; Hwang, M.; Jeon, T.; George, A.T.; Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative. Fractal dimension analysis of the cortical ribbon in mild Alzheimer’s disease. NeuroImage 2010, 53, 471–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicastro, N.; Malpetti, M.; Cope, T.E.; Bevan-Jones, W.R.; Mak, E.; Passamonti, L.; Rowe, J.B.; O’Brien, J.T. Cortical Complexity Analyses and Their Cognitive Correlate in Alzheimer’s Disease and Frontotemporal Dementia. J. Alzheimer’s Dis. 2020, 76, 331–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lemmens, S.; Devulder, A.; Van Keer, K.; Bierkens, J.; De Boever, P.; Stalmans, I. Systematic review on fractal dimension of the retinal vasculature in neurodegeneration and stroke: Assessment of a potential biomarker. Front. Neurosci. 2020, 14, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, W. Retinal neurovascular coupling: From mechanisms to a diagnostic window into brain disorders. Cells 2025, 14, 1798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patton, N.; Aslam, T.; Macgillivray, T.; Pattie, A.; Deary, I.J.; Dhillon, B. Retinal vascular image analysis as a potential screening tool for cerebrovascular disease: A rationale based on homology between cerebral and retinal microvasculatures. J. Anat. 2005, 206, 319–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karperien, A.L.; Jelinek, H.F. Morphology and Fractal-Based Classifications of Neurons and Microglia in Two and Three Dimensions. Adv. Neurobiol. 2024, 36, 149–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Varley, T.F.; Craig, M.; Adapa, R.; Finoia, P.; Williams, G.; Allanson, J.; Pickard, J.; Menon, D.K.; Stamatakis, E.A. Fractal dimension of cortical functional connectivity networks & severity of disorders of consciousness. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0223812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molina, R.; Crespo-Cobo, Y.; Esteban, F.J.; Arias, A.V.; Rodríguez-Árbol, J.; Soriano, M.F.; Ibáñez-Molina, A.J.; Iglesias-Parro, S. Dynamic Evolution of EEG Complexity in Schizophrenia Across Cognitive Tasks. Entropy 2025, 27, 226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández-Borkel, T.; Borkel, L.F.; Rojas-Hernández, J.; Hernández-Álvarez, E.; Quintana-Hernández, D.J.; Ponti, L.G.; Henríquez-Hernández, L.A. The Causal Role of Consciousness in Psychedelic Therapy for Treatment-Resistant Depression: Hypothesis and Proposal. ACS Pharmacol. Transl. Sci. 2025, 8, 2839–2847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esteban, F.J.; Galadí, J.A.; Langa, J.A.; Portillo, J.R.; Toscano, F. Informational structures: A dynamical system approach for integrated information. PLoS Comput. Biol. 2018, 14, e1006154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Method | Computational Approach | Advantages | Disadvantages | Typical Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Box-counting | Progressive grid refinement with nonempty box counting; slope from log N vs. log(1/r) plot | Intuitive implementation; applicable to 2D and 3D data; widely validated | Sensitive to image resolution and thresholding; requires careful scale range selection | Structural MRI analysis; cortical folding; white matter complexity |

| Higuchi’s FD | Time-domain curve length calculation at multiple temporal scales | No frequency transformation required; handles nonstationary signals; computationally efficient | Parameter selection affects estimates; sensitive to signal-to-noise ratio | EEG/MEG time series; neurophysiological dynamics; cognitive task analysis |

| Katz’s FD | Ratio of signal length to diameter using Euclidean distance | Fast computation; single-scale estimate; minimal parameters | Less sensitive to subtle complexity changes; limited scale information | Rapid clinical screening; real-time EEG monitoring; preliminary complexity assessment |

| Disease | Affected Tissue | Direction of FD Change | Brain Regions | Clinical Correlations | Study Characteristics |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Multiple sclerosis | White matter border | Decreased | Whole brain, NAWM | Lesion volume; early disease detection | Early to intermediate stages; detects diffuse damage |

| Gray matter | Increased | Whole brain, GM | T1/T2 lesion load; disease subtype | RRMS and CIS patients; correlates with pathology extent | |

| Alzheimer’s disease | Cortical GM | Decreased | Hippocampus, temporal cortex | Cognitive decline; disease severity | Correlates with neuropsychological performance |

| Parkinson’s disease | Subcortical structures | Decreased | Basal ganglia, substantia nigra | Motor symptom severity; disease duration | Reflects neuronal loss and structural degeneration |

| Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis | Motor cortex | Decreased | Precentral gyrus, corticospinal tract | Functional impairment; progression rate | Tracks upper motor neuron degeneration |

| Huntington’s disease | Striatal structures | Decreased | Caudate, putamen | CAG repeat length; functional capacity | Detectable in pre-manifest carriers |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Esteban, F.J.; Vargas, E. Foundations and Clinical Applications of Fractal Dimension in Neuroscience: Concepts and Perspectives. AppliedMath 2026, 6, 7. https://doi.org/10.3390/appliedmath6010007

Esteban FJ, Vargas E. Foundations and Clinical Applications of Fractal Dimension in Neuroscience: Concepts and Perspectives. AppliedMath. 2026; 6(1):7. https://doi.org/10.3390/appliedmath6010007

Chicago/Turabian StyleEsteban, Francisco J., and Eva Vargas. 2026. "Foundations and Clinical Applications of Fractal Dimension in Neuroscience: Concepts and Perspectives" AppliedMath 6, no. 1: 7. https://doi.org/10.3390/appliedmath6010007

APA StyleEsteban, F. J., & Vargas, E. (2026). Foundations and Clinical Applications of Fractal Dimension in Neuroscience: Concepts and Perspectives. AppliedMath, 6(1), 7. https://doi.org/10.3390/appliedmath6010007