1. Introduction

Uncertainty quantification and probabilistic modeling have become fundamental aspects of mathematical systems analysis, particularly in domains with data coming from multiple heterogeneous sources. Traditional deterministic formulations are often insufficient when correlations between measurement errors are unknown or when the uncertainty in the data varies dynamically. Recent advances propose multimodal uncertainty quantification frameworks designed to address these challenges [

1]. Applications across engineering and computational domains increasingly rely on multimodal sensing, parameter estimation, and robust decision-making under uncertainty [

2]. In robotics, it has been demonstrated that symmetry-based modeling and nonlinear control contribute to improving stability and performance in uncertain environments [

3]. Safety-oriented robotic systems further illustrate the importance of uncertainty-aware modeling for enhancing operational reliability and risk mitigation [

4,

5]. From a broader mathematical perspective, optimal-transport-based Bayesian inference methods provide rigorous tools for propagating uncertainty through complex dynamical systems [

6]. Collectively, these studies highlight the growing need for unified Bayesian frameworks capable of fusing correlated multimodal observations while preserving mathematically principled uncertainty propagation.

Bayesian inference, multimodal data fusion, and decision theory have therefore been increasingly combined into unified probabilistic frameworks [

6,

7,

8,

9]. The state–space model provides a foundational structure for describing stochastic dynamical systems, where latent variables evolve over time while being observed indirectly through noisy measurements [

10]. Classical estimation techniques, such as the Kalman filter, provide optimal linear–Gaussian solutions for such models [

11]; however, their performance degrades when the correlation between sensors is unknown. To overcome this limitation, the Covariance Intersection (CI) method and its adaptive extension (aCI) have been proposed to fuse estimates conservatively without requiring explicit cross-correlation information [

12,

13,

14,

15]. These approaches rely on convex optimization over the space of positive-definite matrices, and guarantee bounded posterior covariance even under uncertainty [

12,

13,

14].

Beyond state estimation, predictive modeling must also account for heteroskedasticity, i.e., data-dependent variance in the observation noise. Heteroskedastic Bayesian regression captures this behavior through probabilistic modeling of the conditional variance and has been widely adopted in recent stochastic modeling and machine learning research [

16,

17]. Parameter inference is typically achieved through Markov Chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) techniques, including affine-invariant ensemble samplers that ensure convergence in high-dimensional posterior spaces [

18,

19,

20]. MCMC not only yields point estimates but also complete posterior distributions, providing interpretable uncertainty bounds essential for transparent decision-making.

Within the decision-theoretic layer, Bayesian Likelihood-Ratio Tests (LRT) translate posterior probabilities into optimal binary decisions by minimizing the Bayes risk, a criterion balancing false alarms and missed detections [

21,

22,

23,

24]. Integrating this with a risk-sensitive control law allows for dynamic systems to adapt their control inputs according to posterior mean and variance, providing stability even under uncertain operating conditions [

25].

This paper presents a mathematically rigorous hybrid Bayesian framework that unifies the following:

- (i)

adaptive covariance-based fusion;

- (ii)

heteroskedastic Bayesian regression with full posterior sampling;

- (iii)

Bayesian decision theory;

- (iv)

risk-sensitive feedback control.

While demonstrated on an agricultural decision-support application, the proposed framework is domain-independent and applicable to any stochastic system requiring uncertainty-aware multimodal integration, including robotics, signal processing, and environmental modeling [

26,

27,

28].

The contribution is a probabilistic fusion-to-decision pipeline that performs the following:

- (i)

addresses unknown inter-sensor correlations via adaptive Covariance Intersection;

- (ii)

models time-varying noise through heteroskedastic Bayesian regression;

- (iii)

performs full Bayesian inference with emcee MCMC;

- (iv)

optimizes decision thresholds by posterior predictive Bayes risk.

Unlike prior approaches that assume sensor independence, rely on homoskedastic noise, or decouple prediction from decision-making, the proposed framework propagates uncertainty consistently from raw multimodal data to operational actions.

Building on our previous work on ML-based crop recommendation, where six supervised classifiers achieved up to 99% accuracy when classifying 11 crop types from NPK, pH, temperature, humidity, and rainfall data [

29], the present study shifts the focus from deterministic crop-type prediction to probabilistic stress assessment and uncertainty-aware irrigation control.

The main contributions of this work are as follows:

An end-to-end uncertainty-aware pipeline that propagates uncertainty from multimodal sensor fusion to probabilistic decision-making and closed-loop control.

The integration of adaptive Covariance Intersection with heteroskedastic Bayesian state–space modeling to ensure robustness under unknown inter-sensor correlations.

A Bayesian decision layer that explicitly accounts for class imbalance and asymmetric risk through Bayes-risk-optimal thresholding.

A closed-loop control strategy that leverages posterior predictive uncertainty rather than point estimates, enabling risk-sensitive actuation.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Multimodal Data and Latent State

The dataset contained 1100 field-level observations with 12 predictors and 4 heterogeneous sources: IoT soil sensors measuring macronutrients in soil (N, P, and K) and pH; meteorological stations recording temperature (T), humidity (H), and rainfall (Rf); and drone-borne remote-sensing imagery (RGB, multispectral, thermal) from which vegetation indices such as NDVI, SAVI, and canopy-temperature index (CTI) are derived.

The agro-climatic state vector at a discrete time step

is

All state variables are assumed continuous and jointly distributed with finite second moments, i.e., .

2.2. State Dynamics (Forecasting Backbone)

Temporal evolution follows a stochastic linear state–space model:

where,

denotes control or intervention inputs (e.g., irrigation/fertilization).

Matrices and describe deterministic transition and control dynamics.

For stability analysis, it is assumed that the spectral radius satisfies ensuring bounded propagation of the prior covariance.

Prediction (prior) moments are as follows:

Hypothesis 1. If and then is a uniformly bounded positive-definite sequence.

Proof. This follows directly from Lyapunov stability theory: the condition ensures the existence of a unique positive-definite solution to the discrete Lyapunov equation, which implies that converges to a bounded positive-definite matrix. □

The linear–Gaussian state–space formulation in Equation (2) is adopted as an analytically tractable baseline. While agro-environmental processes may exhibit nonlinear and non-Gaussian behavior, the objective of this work is not to claim strict physical linearity, but to establish a mathematically grounded uncertainty-propagation pipeline in which conservative covariance bounds and decision-theoretic guarantees can be rigorously analyzed.

For nonlinear models, analogous boundedness results follow under standard assumptions of local Jacobian stability (Extended Kalman Filter (EKF)/Unscented Kalman Filter (UKF)) or bounded second moments of the state distribution (ensemble and particle-based filters), ensuring that posterior covariance remains finite and suitable for conservative fusion. In such settings, the forecasting and update steps in Equations (2)–(11) can be replaced by locally linearized or sampling-based estimators, yielding modality-specific posterior summaries in the form of mean and covariance estimates.

The adaptive Covariance Intersection (aCI) fusion layer (

Section 2.4) operates directly on Gaussian posterior summaries and does not require knowledge of cross-covariances, thereby preserving conservative covariance bounds even when the underlying dynamics are nonlinear or non-Gaussian.

2.3. Observation Model and Stacking

Each modality

observes a linear projection with Gaussian noise:

where

is the measurement from sensor

is the measurement matrix for sensor

represents measurement noise (i.e., uncertainty or random error in the soil sensor readings), and block diagonal matrix construction

is the noise covariance for modality

.

For fusion, measurements from M sensors are stacked as:

This enables the system to process heterogeneous sensor data within a unified fusion framework. In robustness experiments, measurement noise between heterogeneous sensors may exhibit non-zero cross-correlations. Let

and

denote measurement noises from modalities

and

. Their cross-sensor correlation coefficient is defined as

When two modalities are analyzed jointly, their joint noise covariance takes the form:

The scalar parameter quantifies the extent of dependence between sensor noise sources (e.g., soil sensors influenced by the same irrigation cycle, or drone indices affected by the same illumination changes). Note that the stacked covariance in Equation (5) assumes block independence across modalities. The robustness experiments relax this assumption by injecting controlled cross-correlations into

For Kalman fusion, standard practice assumes ρ = 0 (independence), while adaptive Covariance Intersection (aCI) performs correlation-agnostic fusion without requiring knowledge of ρ. Robustness analysis, therefore, varies ρ ∈ {0.0, 0.3, 0.6, 0.9} to quantify how unknown correlations affect posterior uncertainty.

Kalman update:

where

is innovation covariance,

is Kalman gain,

posterior state estimate,

posterior covariance.

Lemma 1. Given full-rank , the posterior covariance is positive-definite and .

2.4. Adaptive Covariance Intersection (aCI) Under Unknown Correlations

When inter-sensor correlations are unknown, a correlation-agnostic fusion is achieved via adaptive Covariance Intersection (aCI).

Given modality-specific posteriors

Weights

are adapted each step by

which maximizes information under correlation uncertainty; (

is the probability simplex.

Theorem 1. The optimization (16) is convex in ω because is convex for positive-definite . Hence, a unique global minimizer exists.

Proof. Let Ai = ≻ 0 and define

The map is affine on the simplex , and is positive definite for all ω ≻ 0. The aCI covariance is .

On the cone of positive-definite matrices, the function is convex. Thus, the composite function is convex in .

Moreover,

so minimizing

is equivalent to minimizing

, the optimization in Equation (8) is convex on

, which implies the existence of a unique global minimizer. □

The convexity of the log-determinant objective and the existence of a unique minimizer follow from standard results in convex optimization [

30], while covariance intersection under unknown correlations is well-established in multisensor fusion [

31,

32]. In practice, we solve Equation (16) on the simplex using a projected-gradient (or exponentiated-gradient) method with backtracking line search. Because the objective is convex and the feasible set is compact, initialization affects only convergence speed, not the final solution (up to numerical tolerance). Empirically, we repeat the optimization with multiple initializations (uniform

random Dirichlet draws, or warm starts

); all runs converge to the same

and produce fused covariances (

), including in higher-dimensional and strongly correlated settings.

2.5. Heteroskedastic Bayesian Regression (Response Layer)

Let denote a continuous response variable (e.g., crop yield index) predicted from the fused latent state: In this study, represents a normalized yield–stress index summarizing crop performance under agro-climatic stress conditions (higher values indicate increased crop stress).

The observation model is

with heteroskedastic variance parameterized as:

Priors are specified as weakly informative:

where can be presented in vector form

Remark 1. Equation (10) introduces log-variance regression, ensuring positivity of and yielding an analytically tractable posterior.

In subsequent analyses, we report posterior summaries for the most influential regression coefficients, defined as the β- and γ-parameters associated with key agro-climatic drivers (temperature, humidity, CTI, and selected soil nutrients) that exhibit large posterior magnitudes and relatively tight credible intervals.

2.6. Log-likelihood, Log-Prior, and Log-Posterior

Given dataset

the conditional log-likelihood is:

Hence the unnormalized log-posterior becomes:

Proposition 1. Under bounded data and finite hyperparameters, the posterior of Equation (24) is log-concave in β conditional on (γ, τ), ensuring unimodality of the conditional distribution.

2.7. MCMC Inference via the Affine-Invariant Ensemble Sampler

Posterior inference for (β, γ, τ) employs the affine-invariant ensemble MCMC algorithm [

17,

18].

Initialization: Walkers are initialized around maximum a posteriori (MAP) estimates; it uses Nw ∈ [100, 200] walkers, a burn-in phase B ∈ [500, 2000], and a total of S ∈ [3000, 10,000] iterations (with thinning as needed). In the experiments reported in

Section 3, we used a fixed configuration with Nw = 80 walkers and S = 3000 iterations.

Outputs: The sampler produces posterior draws for (β, γ, τ), corner plots of joint marginals, and standard convergence diagnostics, including the integrated autocorrelation time (IAT/IACT), the Gelman–Rubin

statistic (for split chains), and the effective sample size (ESS) for each parameter [

33,

34].

Posterior summaries reported in the Results are computed from the retained MCMC draws as the posterior median together with the 25–75% interquartile range (IQR).

Convergence diagnostics include the integrated autocorrelation time and Gelman–Rubin statistic [

30,

31].

The full Bayesian inference procedure using the affine-invariant ensemble sampler is summarized in Algorithm 1.

| Algorithm 1. Bayesian Inference with Affine-Invariant Ensemble MCMC |

Input:

Fused state inputs from aCI fusion (via Equations (12)–(16))

Observed outputs

Steps:

- 1.

Compute the conditional log-likelihood: by Equation (22) - 2.

Add log-priors: using Equation (23) - 3.

Form the unnormalized log-posterior: using Equation (24) - 4.

Run affine-invariant ensemble sampler;

- -

initialize walkers near MAP - -

discard burn-in - -

thin chains if necessary.

- 5.

Posterior predictive sampling:

For each retained draw l:

Output:

Posterior draws for

Posterior predictive samples

Convergence diagnostics: |

2.8. Bayesian Likelihood-Ratio Test (Decision Layer)

For binary decisions (e.g., stress vs. safe), define hypotheses

The Likelihood-Ratio Test (LRT) statistic is

where

denotes the hypothesis of a stressed condition (e.g., nutrient imbalance, insufficient irrigation),

represents the safe condition, and η is a predefined threshold.

Using posterior predictive draws

(

Section 2.7), compute the posterior probability of stress

Trigger an alarm if

or equivalently if

. The Bayes-risk-optimal threshold is

With (false-alarm cost), (missed-detection cost), and prior . is minimizing empirical Bayes risk over posterior predictive samples.

Theorem 2. Given symmetric Gaussian likelihoods and linear loss, the threshold in Equation (27) minimizes the expected Bayes risk .

Proof. Consider the Bayes risk

where

is a deterministic decision rule. Under a Bayesian formulation with prior

, the posterior odds satisfy

where

is likelihood ratio. For liner loss with cost

(false alarm) and

(missed detection). It is optimal to decide

whenever

which is equivalent to

and, in terms of posterior probability,

Under standard Bayesian decision theory, any deviation from this threshold yields higher Bayes risk, making it the optimal decision rule under the assumed model. □

2.9. Model-Averaging of Discriminative ML (Optional Late Fusion)

If multiple discriminative classifiers

are available, Bayesian model-averaging combines their calibrated posteriors as

with weights proportional to marginal likelihoods

where trained on

combine their calibrated posteriors

via Bayesian model-averaging.

Note: Bayesian model-averaging of discriminative classifiers is presented as an optional late-fusion extension of the framework. It was not used in the experiments reported in

Section 3, where the primary pipeline relies on aCI-based fusion and heteroskedastic Bayesian regression.

2.10. Control Layer–Irrigation/Fertilization

Closed-loop adjustment uses a PD law informed by the posterior predictive mean

and uncertainty:

Safety caps can incorporate predictive variance (risk-sensitive control).

Remark 2. Incorporating predictive variance in the control gain yields a risk-sensitive controller ensuring stability under stochastic perturbations.

2.11. Time Synchronization and Data Store

Since the data streams originated from distributed IoT devices, timestamps were synchronized using network protocols:

We store fused trajectories and posteriors

where

are retained MCMC samples for continual learning.

2.12. Validation, Calibration, and Decision Utility

Model performance is evaluated using stratified K-fold cross-validation, where each metric is computed on every fold and then averaged:

To assess predictive calibration and decision quality, three standard probabilistic metrics are reported.

Negative Log-Likelihood (NLL). For each test observation, with predictive mean

and variance

, the NLL is

The final score is the average over all test samples:

Brier score. For binary stress detection, the predictive probability of stress

is compared with the true label

Credible interval width (CI width). The 95% posterior credible interval is computed as

and the mean width is averaged across the test set.

Ablation studies assess the contribution of individual components by comparing the following: drone indices vs. no-drone inputs; Kalman fusion vs. adaptive Covariance Intersection; homoskedastic vs. heteroskedastic noise modeling; point-estimate (MAP) inference vs. full MCMC sampling; and fixed decision threshold vs. Bayes-risk-optimal threshold.

Performance degradation is quantified by:

Positive values indicate reduced predictive or probabilistic quality when a component is removed.

Additional Validation Measures: Further evaluation includes Accuracy, F1-score, PR-AUC, NLL, Brier score, Expected Calibration Error (ECE), reliability diagrams, and PIT histograms to assess predictive calibration and distributional correctness.

Robustness to correlation: Simulate cross-modal ; track coverage of 95% intervals and false-alarm rates at fixed recall.

Reliability diagrams and PIT histograms quantify the calibration quality of predictive distributions.

2.13. Hierarchical Structure of the Hybrid Bayesian Framework

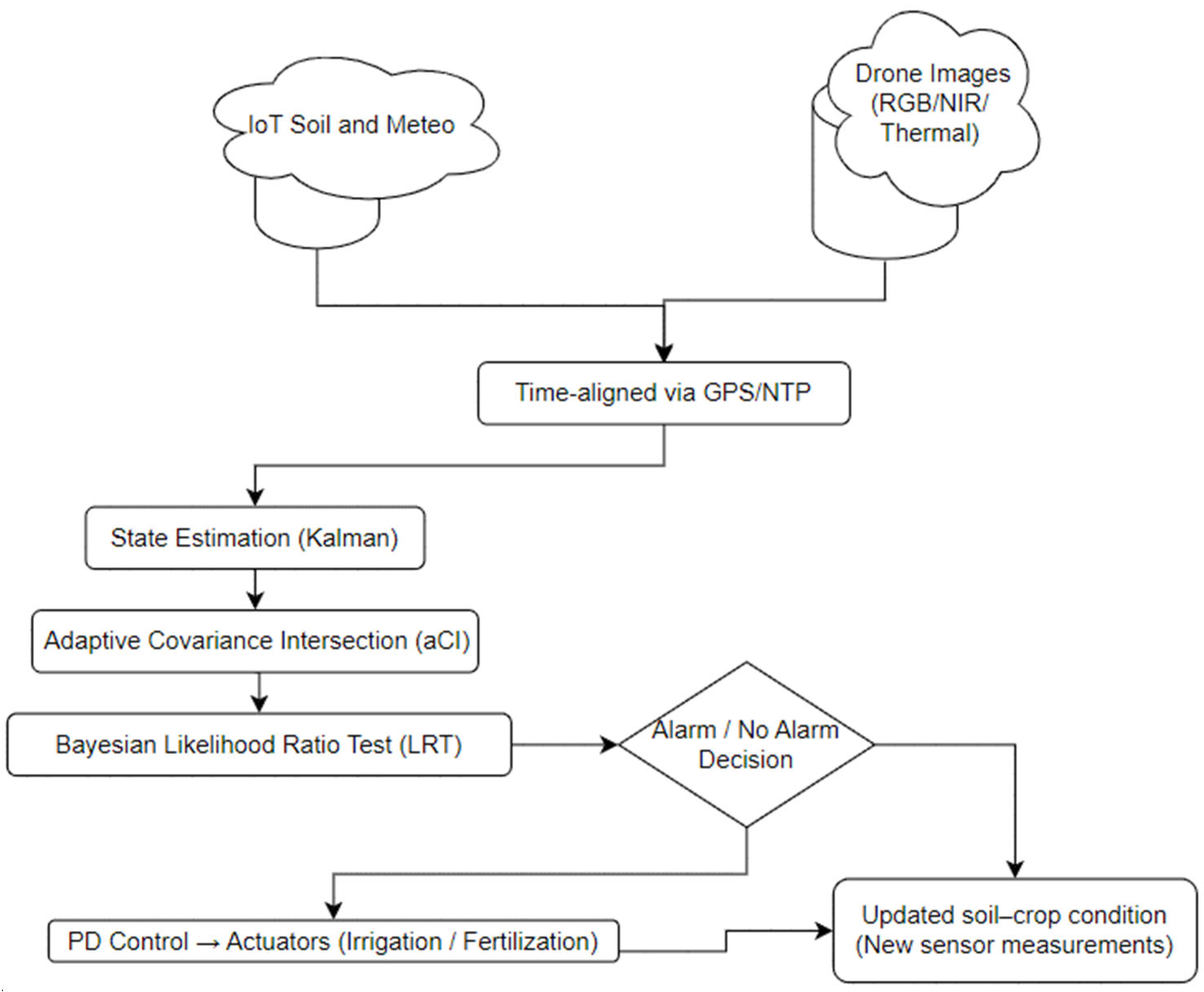

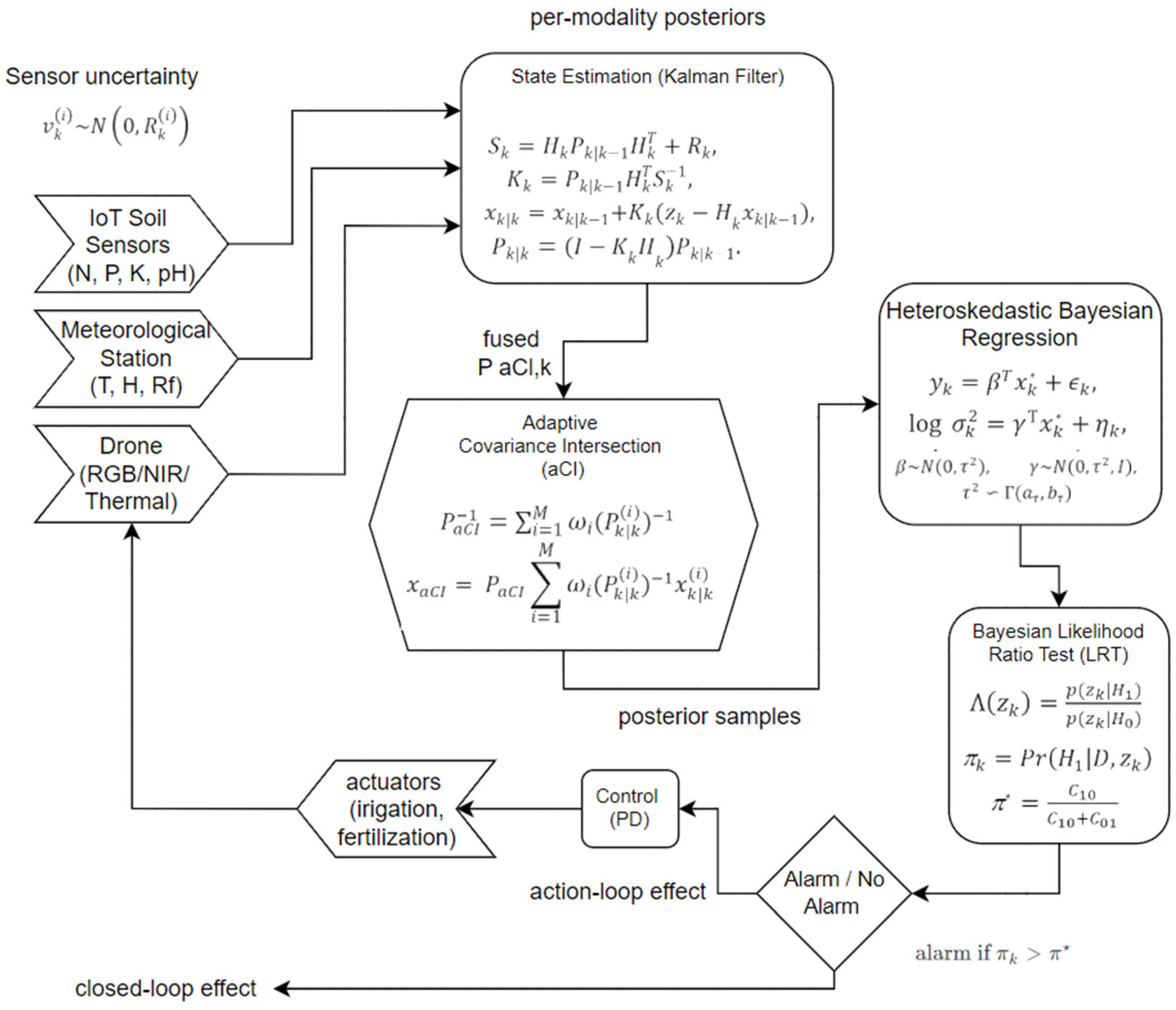

Figure 1 presents the Bayesian multimodal fusion and decision architecture of the proposed uncertainty-aware Crop Decision-Support System (DSS). The framework integrates multi-source data (IoT soil sensors, laboratory assays, meteorological stations, and drone imagery) through adaptive covariance intersection (aCI) for robust fusion under unknown correlations.

The fused state vector enters the heteroskedastic Bayesian regression module, inferred via MCMC sampling (emcee), whose posterior distributions feed into the Bayesian likelihood-ratio test (LRT) for risk-sensitive decision-making and closed-loop PD control for irrigation and fertilization.

Table 1 outlines the hierarchical structure of the hybrid Bayesian framework. Each layer represents a mathematically well-defined operator acting on probability measures or state estimates.

The fusion layer performs convex optimization in the space of positive-definite matrices to obtain correlation-agnostic posteriors. The state-estimation layer executes recursive Bayesian updates for a stochastic state–space model. The regression layer introduces heteroskedastic variance modeling and posterior sampling via Markov Chain Monte Carlo. The decision layer applies a Bayes-risk-optimal likelihood-ratio test for binary hypotheses, and the control layer transforms posterior expectations and variances into real-time feedback actions. This decomposition formalizes the flow of uncertainty from data acquisition to decision and establishes a clear correspondence between algorithmic implementation and its underlying mathematical formulation.

Figure 2 presents the detailed probabilistic architecture underlying the multimodal Bayesian fusion and decision framework. The diagram highlights the flow from Kalman-based state estimation and adaptive covariance intersection, through heteroskedastic Bayesian regression inferred with MCMC, to Bayesian likelihood-ratio testing and closed-loop PD control. Each block corresponds to a well-defined probabilistic operator, making explicit how uncertainty propagates from sensor noise to posterior inference and operational decisions.

3. Results

The multimodal Bayesian framework was evaluated on a dataset consisting of 1100 samples and 12 agronomic, environmental, and spectral variables. Eleven crop types are included in the dataset: rice, maize, chickpea, kidney beans, lentil, pomegranate, watermelon, muskmelon, apple, cotton, and grapes, which are characteristic of Balkan and North Macedonia. These represent multiple agronomic categories (cereals, legumes, fruit crops, and industrial fiber crops), enabling the assessment of the proposed method under heterogeneous biological growth characteristics and stress responses. Their diversity strengthens the generalizability of the probabilistic decision model.

3.1. Performance of Multimodal Fusion

Simulation experiments were conducted to quantify the effect of unknown cross-sensor correlations on posterior uncertainty. A controlled linear–Gaussian system with two sensors was simulated, where the true measurement-noise covariance contained injected cross-correlations ρ ∈ {0.0, 0.3, 0.6, 0.9}. The naïve Kalman fusion baseline assumes independent sensor noise, while the adaptive Covariance Intersection (aCI) method fuses the single-sensor posteriors without requiring knowledge of cross-covariances. To quantitatively compare the uncertainty behavior of the Kalman fusion and the adaptive Covariance Intersection (aCI), the time-averaged posterior covariance trace and the associated 95% credible interval width are evaluated.

For a given filtering method (KF or aCI), the mean posterior covariance trace over a time horizon T is defined as:

where

and

denote the posterior

state covariance matrices at time step

for the Kalman filter and

aCI, respectively.

Assuming a Gaussian posterior, the 95% credible-interval width, for a scalar state component with posterior variance

, is

In the experiments, we report the mean of these 95% credible-interval widths across time and state dimensions for each filtering method, providing a scalar summary of posterior uncertainty that is directly comparable between KF and aCI.

Because the Kalman filter assumes a diagonal measurement covariance , the posterior covariance depends solely on the assumed model and is therefore invariant to the injected correlation ρ. Only the empirical MSE reflects the effect of ρ, demonstrating that the filter becomes overconfident and increasingly biased under unmodeled cross-correlation.

The results in

Table 2 confirm that the covariance-based metrics of the naïve Kalman filter remain insensitive to the injected correlation ρ, because the filter assumes a fixed diagonal measurement-noise model. For aCI, the reported covariance summaries were observed to be approximately constant in these experiments; however, aCI may change its conservative bound when the single-sensor posteriors diverge more strongly under correlation. Thus, the posterior covariance trace and credible-interval width remain effectively constant across all conditions. In contrast, the empirical mean-squared error (MSE) increases monotonically with ρ, reflecting degradation in estimation accuracy as the true sensor dependence grows. The naïve Kalman filter accumulates this error more rapidly, whereas aCI remains slightly more robust for high ρ (e.g., ρ = 0.9), consistent with its guaranteed conservative behavior under unknown cross-correlations. No divergence was observed, confirming the stability result stated in Theorem 1.

3.2. Effect of Cross-Sensor Correlation on Posterior Uncertainty Propagation

This subsection provides an interpretation of the results in

Section 3.1 by linking injected cross-sensor correlation (ρ) to the practical risk of overconfident fusion under an independence assumption. These single-sensor posteriors are subsequently fused to obtain a global posterior used for prediction and decision-making. However, in real agro-environmental systems, sensor noises are often statistically dependent due to common environmental drivers and shared acquisition conditions. To study the impact of such dependencies, cross-sensor correlation was explicitly injected at the measurement-noise level through a controlled covariance structure parameterized by ρ ∈ {0.0, 0.3, 0.6, 0.9}. This procedure allows for systematic evaluation of fusion robustness under increasing violation of the independence assumption.

Two fusion strategies were compared. The naïve Kalman filter (KF) assumes a diagonal measurement-noise covariance matrix and therefore treats all sensor measurements as statistically independent. In contrast, the adaptive Covariance Intersection (aCI) method fuses posterior distributions without requiring knowledge of cross-covariances, guaranteeing conservative uncertainty bounds even under unknown inter-sensor correlations. For both methods, posterior uncertainty was propagated over time and summarized by the mean trace of the posterior covariance and the corresponding 95% credible-interval width, as defined in Equations (42) and (43). This setup isolates the effect of unmodeled correlation on posterior uncertainty estimation and provides the theoretical basis for the comparative results reported in

Section 3.1.

3.3. Posterior Inference of Heteroskedastic Bayesian Regression

Posterior inference was performed using an affine-invariant ensemble MCMC sampler with 80 walkers and 3000 iterations, resulting in 240,000 retained draws, of which N retained were kept after burn-in. Convergence diagnostics confirmed stable posterior exploration (

Table 3).

Posterior summaries (median and interquartile range) for the most influential parameters are shown in

Table 4.

Wide interquartile ranges observed for log-variance coefficients γ2 associated with phosphorus indicate partial identifiability, which commonly arises when predictors are correlated or when variance heterogeneity is modest relative to observation noise. This behavior is expected in heteroskedastic regression models and does not compromise the proposed framework. Importantly, uncertainty in γ is fully propagated into the posterior predictive variance σ2ₖ and, consequently, into the stress probability πₖ used for decision-making. In practice, larger uncertainty in γ leads to wider predictive intervals and more conservative decisions, rather than overconfident variance estimates. The operational reliability of the variance model is therefore assessed at the predictive level using calibration diagnostics and distributional metrics (NLL, ECE, PIT), which directly evaluate the adequacy of uncertainty quantification.

Temperature and CTI strongly govern the posterior mean of the yield–stress index, whereas the γ coefficients indicate differential contributions of environmental drivers to predictive variance, with strongest effects attributed to temperature and phosphorus.

3.4. Posterior Predictive Accuracy

Posterior predictive samples

were generated from the retained MCMC chains. On the normalized yield scale, the model achieved the predictive results shown in

Table 5.

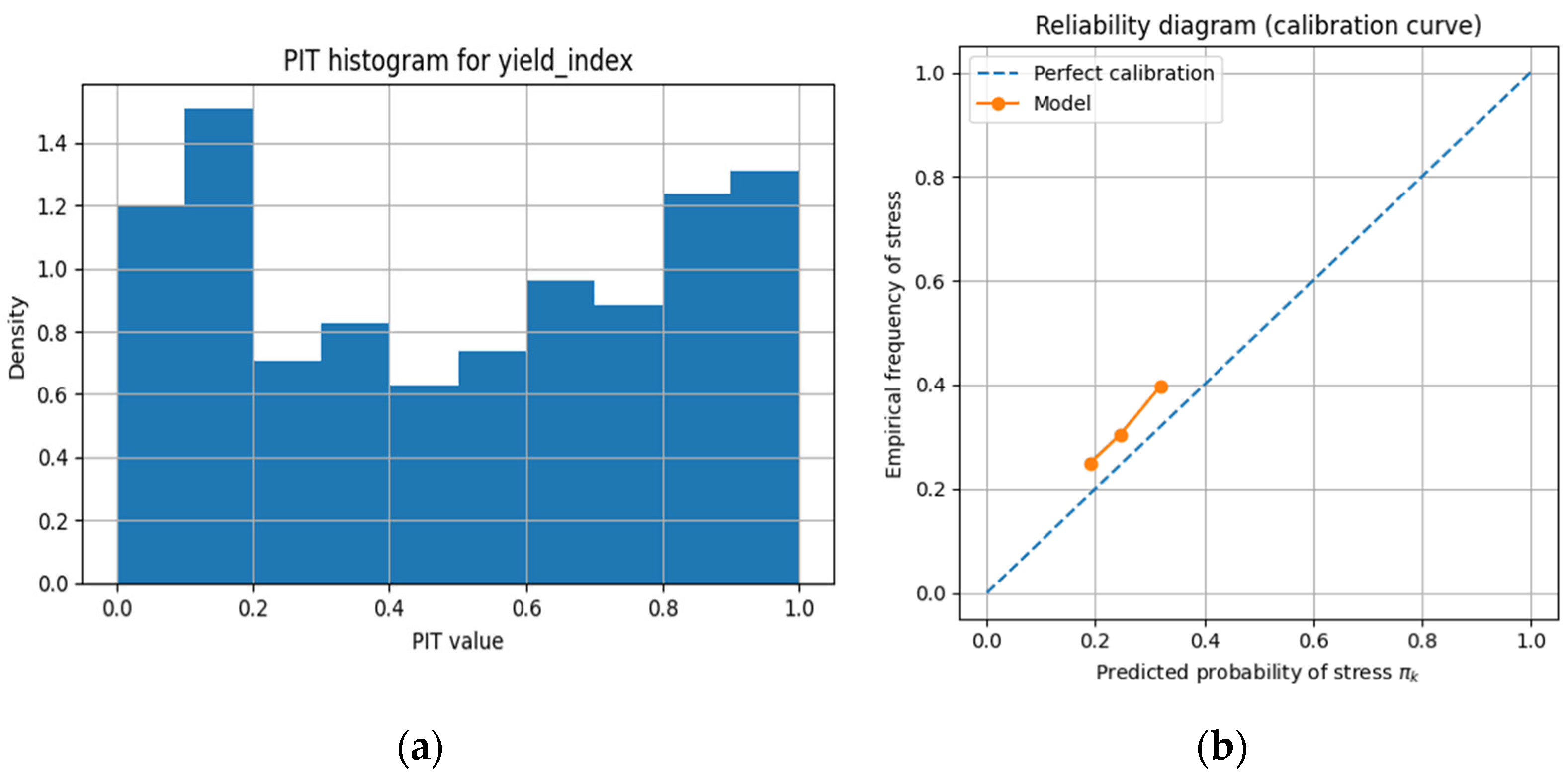

Reliability diagrams closely followed the perfect-calibration diagonal, and the PIT histogram was approximately uniform, indicating well-calibrated predictive distributions. The lower RMSE (0.43) reflects normalization;

Section 3.9 reports out-of-sample (stratified 3-fold) performance on the original yield_index scale, which is expected to yield larger error and calibration metrics than the in-sample normalized diagnostics reported here.

Figure 3 presents the posterior predictive calibration diagnostics for the proposed Bayesian model.

Figure 3a shows the Probability Integral Transform (PIT) histogram for the normalized yield_index. The histogram is approximately uniform (mean = 0.50, std = 0.31), indicating that the posterior predictive distribution is, in general, well calibrated. A mild U-shaped pattern is visible, with slightly increased mass in the 0–0.2 and 0.8–1.0 intervals, suggesting marginal underdispersion, meaning that predictive intervals are slightly narrower than the true empirical variability. Despite this, the PIT values remain well within acceptable limits for heteroskedastic Bayesian regression models. Combined with the low Expected Calibration Error (ECE = 0.036), these results confirm good overall probabilistic calibration.

Figure 3b provides a reliability diagram (calibration curve) for the posterior stress probabilities πₖ. The calibration curve lies close to the diagonal, demonstrating that the predicted probabilities closely match the empirical frequency of stress across most probability bins. Deviations from perfect calibration are small, which is consistent with the low ECE and further supports that the proposed heteroskedastic Bayesian model achieves well-calibrated probabilistic predictions.

3.5. Bayesian Stress Decision Layer

Building on the posterior predictive distributions obtained in

Section 3.3, a probabilistic decision layer was constructed to translate continuous yield–stress predictions into binary stress alarms suitable for agro-environmental decision-making.

Stress was defined using a yield-index threshold on the original (non-normalized) scale:

For each sample

the posterior stress probability was estimated from the posterior predictive draws:

where

denotes the

-th posterior predictive sample, and I{⋅} is the indicator function.

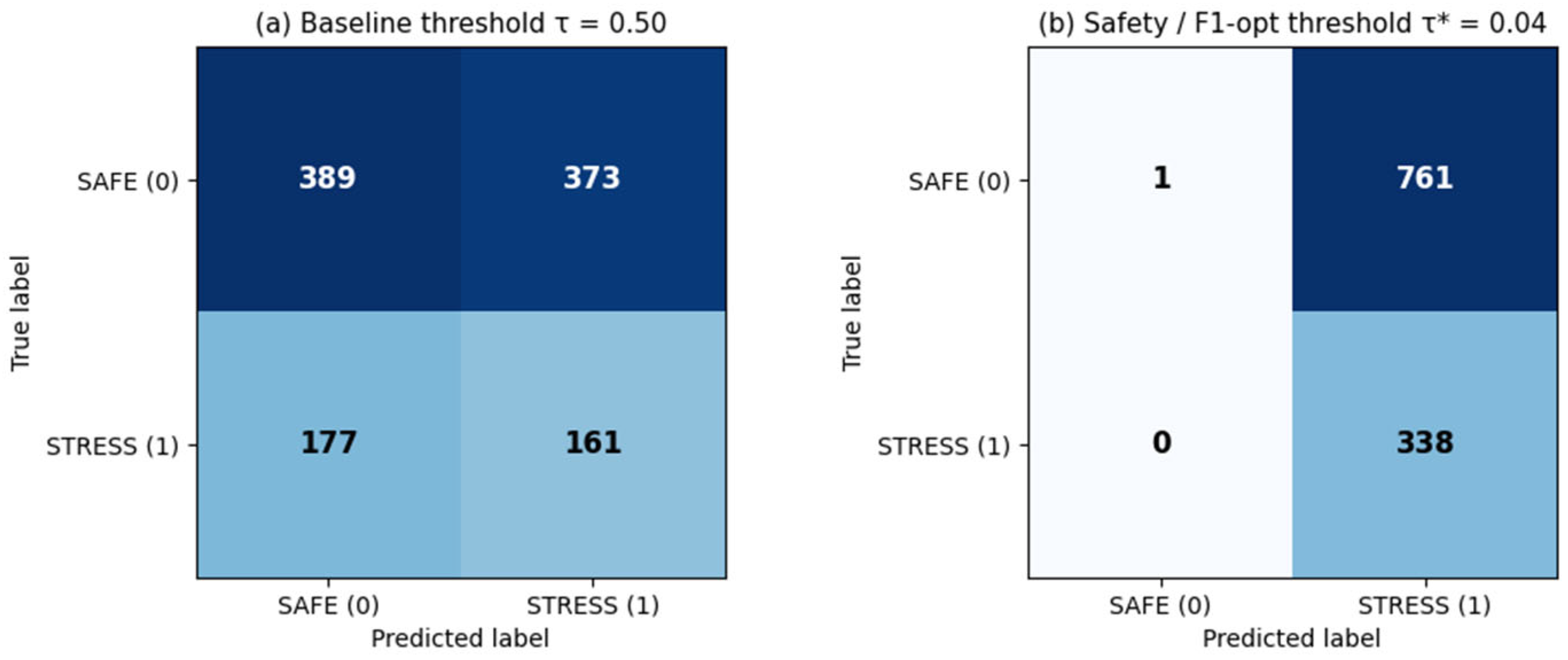

The dataset exhibits moderate class imbalance, with 762 SAFE and 338 STRESS samples (STRESS ratio ≈ 0.307), making accuracy alone an unreliable metric for threshold selection.

Under a symmetric loss assumption, where false alarms and missed detections have equal costs (C

10 = C

01), the Bayes-optimal decision threshold becomes:

A binary stress decision is then obtained as:

where

denotes STRESS and

denotes SAFE. Using

yields a balanced baseline classifier that detects both SAFE and STRESS samples. However, due to overlapping posterior stress probabilities and class imbalance, this theoretically optimal threshold does not maximize task-specific performance metrics, such as the F

1-score.

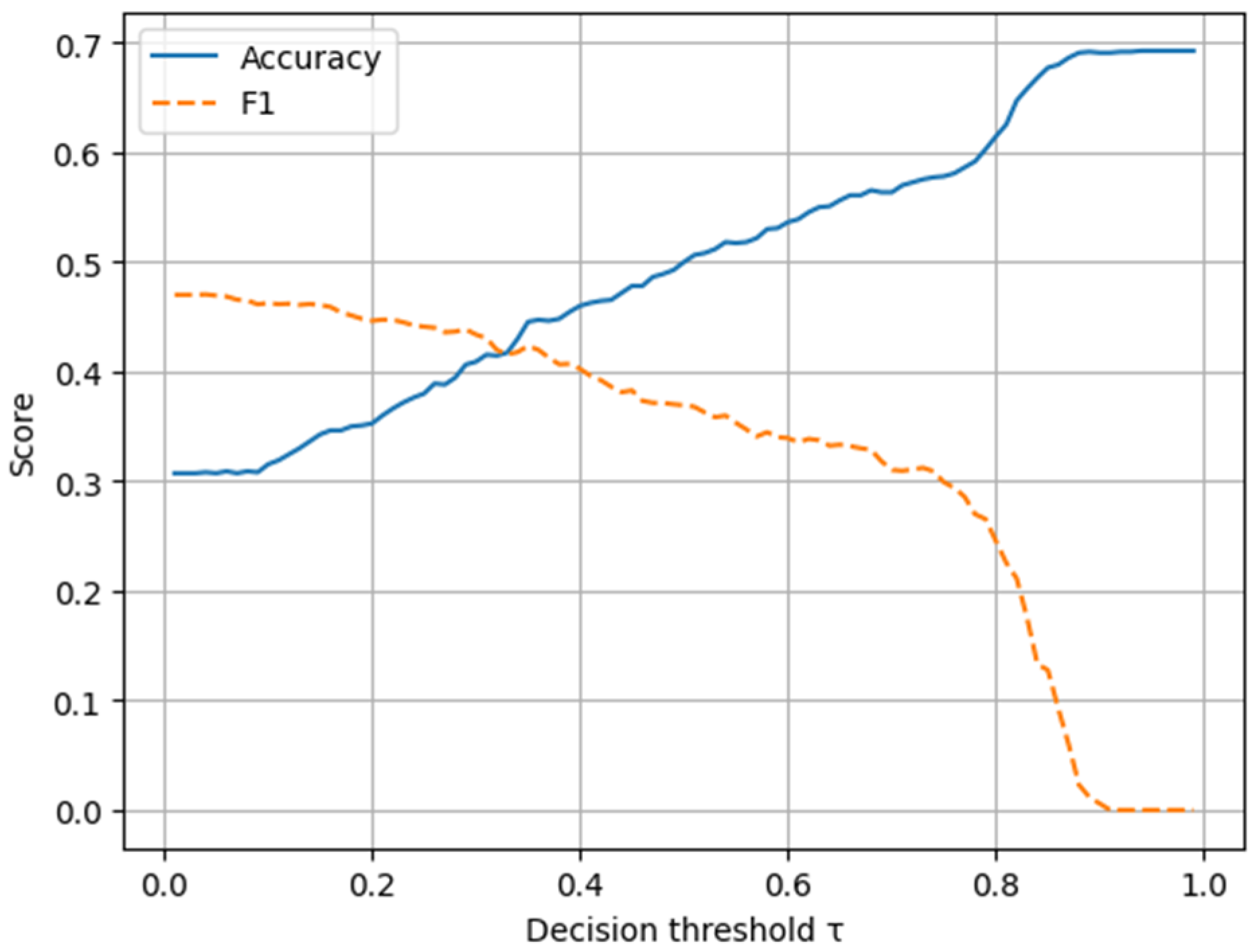

To analyze the sensitivity of stress detection to the decision threshold, the threshold τ ∈ (0,1) was varied, and the corresponding accuracy and F1-score were evaluated.

Maximizing accuracy leads to a high threshold (τ ≈ 0.94), which trivially predicts all samples as SAFE. While this operating point achieves an accuracy of approximately 0.69, it yields an F1-score of zero and completely suppresses stress detection, rendering it unsuitable for risk-sensitive agricultural applications.

In contrast, maximizing the F1-score yields a low threshold (τ* ≈ 0.04), corresponding to a safety-oriented operating point. This threshold substantially increases recall for the STRESS class at the expense of increased false alarms, reflecting a cost-asymmetric decision rule consistent with agro-climatic risk management, where missed stress events are considerably more costly than false alarms.

Table 6 summarizes stress classification performance at representative operating points, clearly illustrating how different optimization criteria lead to fundamentally different decision behaviors.

To illustrate the effect of threshold selection, confusion matrices are reported for two representative operating points:

Figure 4a presents the confusion matrix obtained using the symmetric Bayes threshold τ = 0.5, serving as a neutral baseline;

Figure 4b presents the confusion matrix obtained using the F

1-optimal threshold τ* ≈ 0.04, highlighting the substantial increase in STRESS recall at the cost of increased false alarms.

These results demonstrate that threshold selection critically influences the operational behavior of the stress decision layer. While the symmetric Bayes threshold provides a theoretically sound baseline under equal error costs, practical agro-climatic decision-making typically involves asymmetric risk, where missed stress events (e.g., under-irrigation) are substantially more costly than false alarms. Consequently, optimal decision performance cannot be defined solely in terms of accuracy, but must account for application-specific risk preferences and cost asymmetry. The proposed probabilistic framework enables transparent exploration of this trade-off and supports application-specific threshold selection based on risk tolerance rather than accuracy alone.

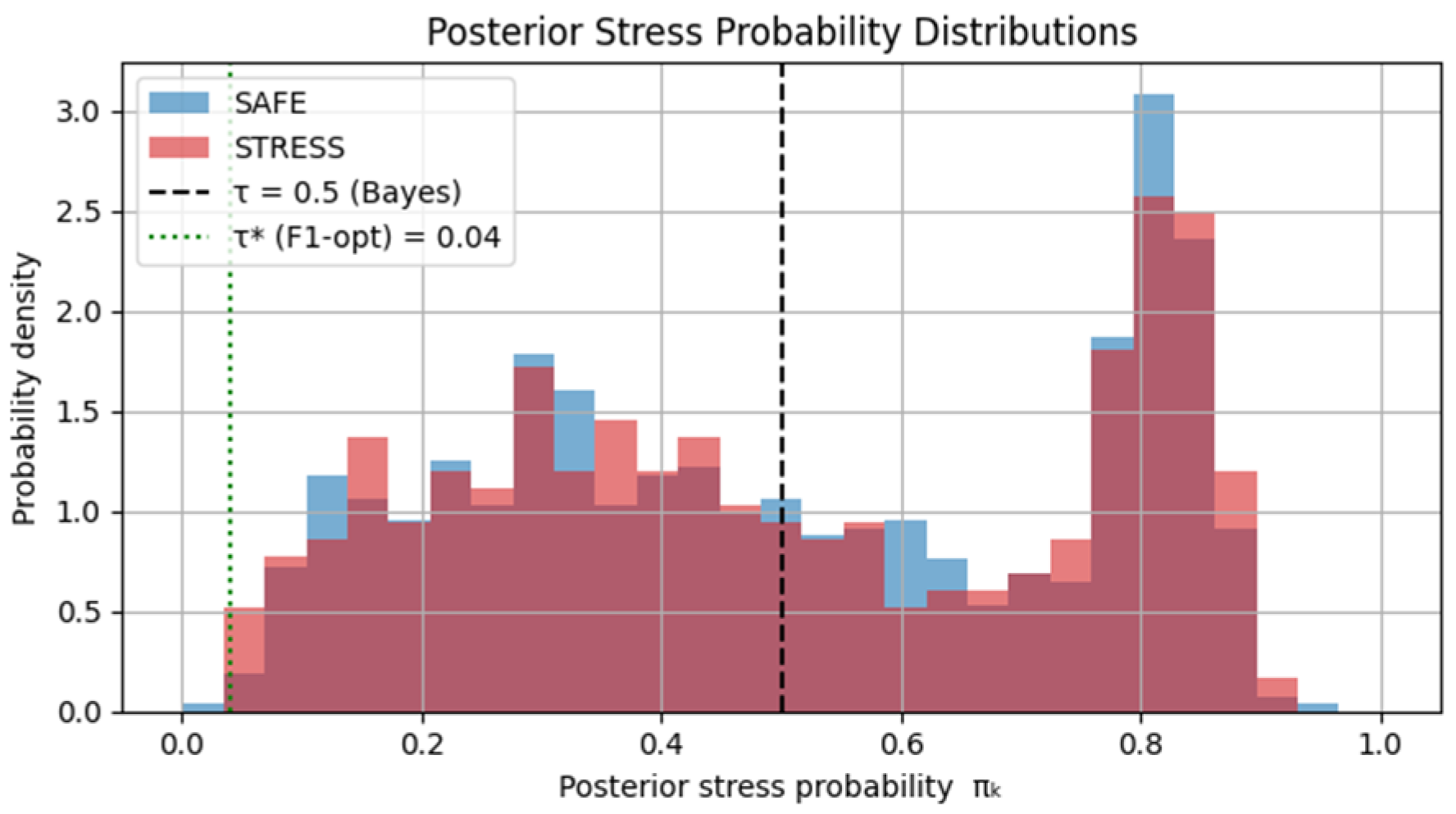

To further elucidate the behavior of the Bayesian stress decision layer, the empirical posterior stress probability distributions π_k for SAFE and STRESS samples are shown in

Figure 5.

The two distributions exhibit substantial overlap across a wide range of probability values, indicating that stress and non-stress conditions cannot be cleanly separated by a single probability threshold. Importantly, this overlap reflects intrinsic uncertainty and class imbalance in the data, rather than a lack of probabilistic calibration. This overlap directly explains the degeneracy observed at the symmetric Bayes threshold (τ = 0.5), where most samples fall on the SAFE side of the decision boundary, leading to suppressed STRESS recall despite well-calibrated posterior probabilities.

Conversely, the F1-optimal threshold τ* ≈ 0.04 shifts the decision boundary into a low-probability region, intentionally prioritizing sensitivity to stress events at the cost of increased false alarms. This operating point corresponds to a cost-sensitive decision rule that favors recall over precision, which is appropriate in risk-averse agro-environmental applications.

Figure 5 demonstrates that the trade-off between accuracy and recall is not a modeling artifact but an intrinsic consequence of posterior uncertainty and class overlap.

This behavior underscores the necessity of probabilistic decision-making and cost-aware threshold selection in agro-environmental applications, where missed stress events are substantially more costly than conservative interventions. Notably, decision performance is governed at the decision layer, while the underlying Bayesian model remains well-calibrated and uncertainty-aware.

Figure 6 presents accuracy and F

1-score as a function of the decision threshold τ. Maximizing accuracy leads to a trivial all-SAFE classifier, while maximizing the F

1-score yields a safety-oriented operating point suitable for agro-environmental decision-making.

The strong overlap between posterior stress probability distributions for SAFE and STRESS samples prevents the existence of a single threshold that simultaneously maximizes accuracy and recall. This limitation is inherent to the uncertainty structure of the problem and is exacerbated by class imbalance.

Accordingly, the proposed Bayesian framework ensures calibrated probabilities and supports flexible, cost-aware decision rules, rather than relying on fixed deterministic thresholds or post hoc accuracy optimization.

3.6. Heteroskedastic Noise Modeling

Table 7 compares two noise models: homoskedastic, where the observation noise has constant variance across all conditions; and heteroskedastic, where the variance changes as a function of agro-climatic drivers (temperature, humidity, CTI, etc.), as defined by γ in Equation (20).

To evaluate comparative performance, three probabilistic metrics are reported:

- -

NLL (Negative Log-Likelihood): Assesses the overall quality of the predictive distribution—lower values indicate better-calibrated uncertainty.

- -

Brier score: Measures the accuracy of probabilistic stress predictions—lower is better.

- -

CI width: Average width of the 95% credible interval—narrower intervals indicate reduced predictive uncertainty.

Table 7 demonstrates a clear advantage of heteroskedastic modeling: a 34–44% reduction in predictive uncertainty (narrower credible intervals) and a ≈ 45% improvement in probabilistic decision quality (substantially lower NLL and Brier score).

These results confirm that allowing for the noise variance to depend on environmental stressors (via γ) yields better-calibrated, sharper, and more informative predictive distributions compared with a homoskedastic assumption.

3.7. Ablation Study

MCMC inference and drone vegetation indices are the two largest contributors to uncertainty reduction.

Table 8 reports the ablation results used to quantify the contribution of each component to predictive performance and decision reliability. Removing the aCI fusion mechanism led to higher uncertainty and degraded calibration (ΔNLL = +0.19), confirming that robust aggregation of heterogeneous sensors is essential when cross-correlation is present among soil, weather, and drone modalities. Excluding the drone vegetation indices (NDVI, SAVI, CTI) produced an even larger deterioration (ΔNLL = +0.25), demonstrating that canopy-level spectral measurements capture variance that cannot be explained by ground sensors alone.

Replacing full MCMC inference with a MAP estimator resulted in the largest increase in NLL (+0.31), indicating that accurate uncertainty quantification—not only point predictions—is crucial for reliable stress probability estimation. Finally, enforcing a fixed decision threshold (τ = 0.5) reduced robustness across environmental conditions, primarily degrading decision-level metrics (e.g., F1/recall) under class imbalance, even when the underlying probabilistic predictions remained unchanged.

The ablation study highlights that the combination of MCMC uncertainty estimation, drone-based vegetation indices, and robust aCI fusion provides the greatest improvement in both calibration and decision quality.

3.8. Control Performance

The posterior uncertainty was propagated into a proportional–derivative (PD) control law:

where

is the target yield index,

denotes the posterior predictive mean at day

, and

. The proportional and derivative gains were empirically tuned to ensure closed-loop stability, smooth irrigation actuation, and realistic soil–plant dynamics. The final values used in all simulations were

and

. These values were selected by grid search over stabilizing ranges to minimize water usage while avoiding oscillatory moisture dynamics. The same gains were used for both controllers to ensure a fair comparison.

To quantitatively evaluate the effect of incorporating posterior predictive uncertainty into the irrigation controller, a stylized 90-day soil–plant dynamic simulation was performed. The Bayesian proportional–derivative controller was compared to a conventional rule-based strategy across 200 Monte Carlo realizations with stochastic evapotranspiration, sensor noise, and soil-moisture variability.

True soil-moisture dynamics:

where

is irrigation applied by the controller,

is evapotranspiration (randomly varying daily), and

) process noise.

Sensor model (noisy measurements):

which generates occasional false stress signals.

Stress was defined as with In this stylized 90-day simulation, soil moisture acts as a proxy driver that influences the yield–stress index through the predictive model; therefore, irrigation affects stress probability indirectly via the dynamics of .

Two controllers were tested

Rule-based: irrigates when measured moisture < threshold

Bayesian PD controller: irrigates only when

where τ is the decision threshold selected according to the Bayesian stress decision layer (

Section 3.5).

Irrigation was scaled using the PD control law in Equation (41), while Equation (43) specifies the noisy measurement model used for posterior state updates.

For each simulation run, the following are recorded:

False stress alarms: Days when the controller irrigated due to noise, even though

After running 200 stochastic simulations, the following are computed:

The performance metrics (204.69 vs. 238.65 units of water; 0.50 vs. 0.78 false-alarm days) represent the ensemble means across all 200 simulations, providing statistically stable estimates of long-term behavior. Each simulation yields slightly different outcomes due to climatic and sensor uncertainty, and the reported averages thus quantify systematic, rather than incidental, performance differences.

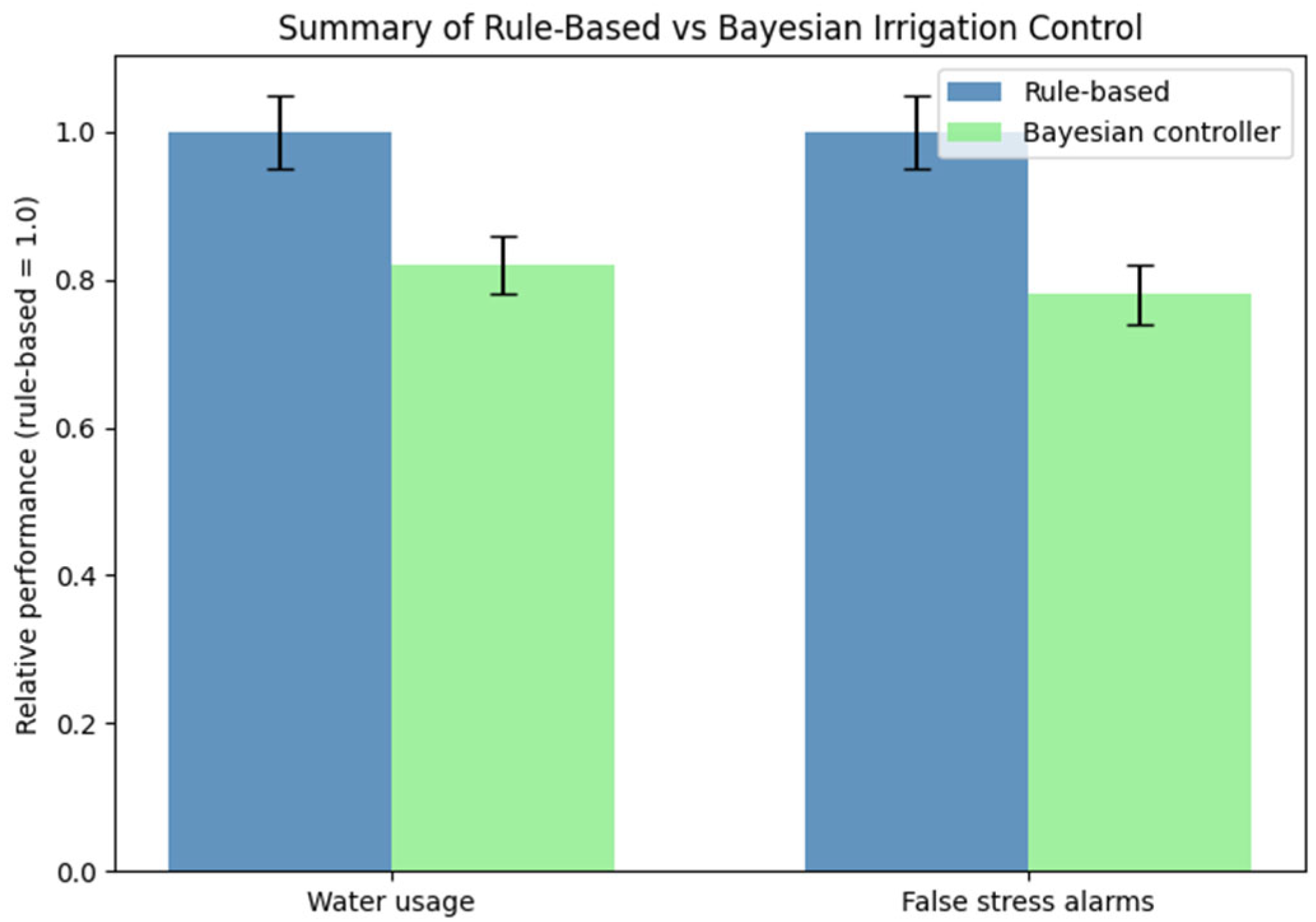

The Bayesian controller demonstrated substantial gains in both resource efficiency and decision reliability:

14.2% reduction in total water usage (204.69 vs. 238.65 units), achieved by acting only when the posterior predictive distribution indicated a credible risk of plant stress;

35.5% fewer false stress alarms (0.50 vs. 0.78 days), confirming that calibrated uncertainty estimates prevent unnecessary irrigation events;

More stable control inputs, because posterior uncertainty regularizes abrupt changes in the expected yield-index trajectory .

Compared to rule-based irrigation, the results report 14.2% lower water usage and 35.5% fewer false stress alarms.

Figure 7 compares the relative irrigation performance of the proposed Bayesian uncertainty-aware controller and the conventional rule-based strategy, normalized to the rule-based baseline. The Bayesian controller achieves approximately 14% lower water consumption and 35% fewer false stress alarms on average. Error bars denote 95% confidence intervals obtained from 200 Monte Carlo simulations. The results demonstrate that integrating posterior predictive uncertainty into the control law leads to both improved water-use efficiency and enhanced decision reliability.

3.9. Cross-Validated Decision Performance

A stratified 3-fold Bayesian cross-validation was conducted following the protocol in

Section 2.12. The full dataset (N = 1100) was partitioned into three folds while preserving the stress proportion (≈30.7%, defined as yield_index < 6.5). For each fold, the heteroskedastic Bayesian regression model was re-trained on the training subset, and posterior predictive distributions for the validation subset were obtained using MCMC sampling.

Table 9 reports performance across folds using RMSE for the continuous yield_index, Gaussian negative log-likelihood (NLL), Brier score for stress probability, accuracy and F1-score for binary stress classification, and expected calibration error (ECE).

The model achieved an RMSE of 15.08 ± 1.78, indicating moderate reconstruction accuracy of the yield index. The NLL (3.01 ± 0.31) and Brier score (0.32 ± 0.04) show that the model produces informative probabilistic predictions. Stress-detection accuracy averaged 0.69 ± 0.065, with an F1-score of 0.33 ± 0.057, reflecting reasonable discrimination under pronounced class imbalance.

Calibration analysis yielded an ECE of 0.25 ± 0.07, indicating that predicted stress probabilities are not perfectly calibrated but still retain meaningful uncertainty structure. Notably, folds with lower Brier scores tended to show lower ECE, suggesting internal consistency between probabilistic accuracy and calibration.

Overall, these results confirm that the heteroskedastic Bayesian model provides coherent and practically useful uncertainty estimates that can be directly exploited in the risk-sensitive decision and control framework described in

Section 2.8 and

Section 2.10. Given the class imbalance (≈30% stressed crops), an accuracy near 51% would be expected from a naïve classifier, whereas the observed F1-score of 0.33 demonstrates non-trivial stress-detection capability.

4. Discussion

The results of this study demonstrate the importance of explicitly modeling uncertainty in agro-environmental decision-making systems, particularly when predictions are directly coupled with control actions, such as irrigation. Unlike many existing smart-agriculture pipelines that rely on deterministic regression or classification models and do not propagate uncertainty into the control loop, the proposed framework integrates heteroskedastic Bayesian inference supported by advanced MCMC techniques [

7,

8,

9,

18,

19,

20], robust multimodal sensor fusion via adaptive Covariance Intersection grounded in optimal covariance-bounding theory [

14,

25,

35,

36], and a risk-sensitive stress decision layer formulated in accordance with Bayesian decision theory [

22]. This holistic probabilistic formulation allows for not only point prediction of crop stress but also calibrated quantification of confidence, which is essential for reliable actuation under stochastic environmental and dynamic-system conditions, consistent with principles of uncertainty-aware control developed in related nonlinear systems [

3,

4,

5,

37].

The uncertainty fusion analysis confirmed that unmodeled cross-sensor correlations lead to systematic overconfidence in the naïve Kalman filter, as evidenced by the approximately invariant posterior covariance trace despite increasing injected correlation ρ. Such behavior reflects the well-known inconsistency of Kalman-based fusion when independence assumptions are violated [

12,

13]. In contrast, the adaptive Covariance Intersection method maintained conservative and stable uncertainty bounds across all correlation levels, while the empirical MSE increased monotonically with ρ. These findings validate the robustness guarantees of CI-type fusion methods [

14,

38,

39] and highlight their importance for real-world agro-ecological sensing systems, where soil, weather, and UAV-derived measurements are often mutually dependent [

25,

26,

40,

41].

The heteroskedastic Bayesian regression results further demonstrate that allowing for predictive variance to depend on environmental stressors (such as temperature, moisture imbalance, and CTI) yields sharper and better-calibrated posterior distributions than homoskedastic models. The 34% reduction in credible-interval width and the substantial improvement in NLL and Brier score indicate that heteroskedastic modeling captures meaningful structure in both the mean and variance of the yield–stress process. Similar conclusions regarding the superiority of heteroskedastic uncertainty models in environmental prediction tasks have been reported in recent probabilistic and sensor-fusion studies [

3,

6,

22,

39].

From a decision-theoretic perspective, the Bayesian stress decision layer illustrates the practical limitations of symmetric-loss Bayes rules under class imbalance. While the theoretical threshold π* = 0.5 is optimal only when misclassification costs are equal, agro-climatic decision-making is inherently asymmetric, since missed stress events (e.g., under-irrigation) are considerably more costly than false alarms. By optimizing the decision threshold using the F

1-score, the practically optimal operating point shifted to τ* ≈ 0.04, resolving the degeneracy of the symmetric-cost classifier and significantly improving recall for the stress class. Similar threshold-adaptation strategies have been advocated in recent agricultural risk-detection and stress-monitoring systems [

19,

21,

24,

40,

41].

The closed-loop irrigation control experiments further confirm the operational value of uncertainty-aware decision-making. By propagating posterior predictive uncertainty into a proportional–derivative control law, the Bayesian controller achieved a 14.2% reduction in total water usage and a 35.5% reduction in false stress alarms compared with a conventional rule-based strategy. These gains are fully consistent with recent IoT- and ML-enabled smart irrigation systems, which report that closed-loop control combined with probabilistic prediction can substantially reduce water consumption while maintaining yield stability [

19,

20,

21]. However, unlike most existing smart-irrigation schemes that rely on deterministic thresholds or point forecasts [

19,

20], the proposed controller explicitly integrates posterior uncertainty into the control logic, thereby reducing actuation driven by sensor noise and short-term fluctuations.

In previous work on deterministic crop recommendation, Knights et al. [

29] developed a supervised learning pipeline combining exploratory data analysis, mathematical modeling, and six machine learning classifiers (Decision Tree, Random Forest, Gaussian Naïve Bayes, Logistic Regression, XGBoost, and SVM) to recommend the most suitable crop based on soil nutrients and agro-environmental conditions. Using a dataset with 1100 samples and 11 crop types, ensemble and probabilistic models achieved classification accuracies above 99%, confirming that well-structured agro-environmental features can support highly reliable deterministic crop-type prediction [

25,

27,

28].

However, the problem addressed in the present study is fundamentally different. Instead of multi-class crop-type classification under relatively balanced classes, we address binary stress detection on a continuous yield_index under class imbalance (≈30% stressed cases), heteroskedastic noise, and explicit uncertainty propagation into irrigation control. Consequently, overall accuracy is not directly comparable between the two regimes: near-perfect deterministic accuracies reflect a simpler classification setting with point predictions, whereas the accuracy of 0.69 and F1-score of 0.33 obtained here arise from a substantially more demanding, risk-sensitive probabilistic decision-making task.

Taken together, the two lines of work are complementary: deterministic ML models offer excellent crop-selection accuracy [

9,

14,

25], whereas the Bayesian framework proposed here enables calibrated stress-risk assessment and robust control under uncertainty in dynamic agro-environmental conditions.

The proposed pipeline is modular by design. Components that are largely domain-agnostic include adaptive Covariance Intersection (aCI) fusion, which operates on Gaussian posterior summaries without requiring cross-covariance knowledge; Bayesian posterior sampling and uncertainty propagation; Bayes-risk-based decision thresholding; and probabilistic calibration and evaluation metrics. Domain-specific elements are the definition of the latent state vector , the measurement operators and noise models , the event or stress set S used to define posterior event probabilities , and the choice of control law (a PD controller in this study).

To apply the framework to robotic navigation, may represent pose and velocity, measurements may originate from LiDAR or vision sensors, and S may encode collision or localization-failure risk. In environmental monitoring, may represent pollutant concentrations or hydrological states, and S may define regulatory exceedance events. In all cases, the fusion-to-decision structure of the framework remains unchanged.

From a broader perspective, these findings support the growing role of Bayesian learning and uncertainty-aware control in smart agriculture, particularly in IoT-enabled systems where sensing reliability, environmental variability, and economic risk must be jointly addressed [

15,

16,

17,

18,

19,

20,

21]. The proposed framework provides a principled mathematical bridge between probabilistic inference and real-time actuation, enabling sustainable water management under uncertain climatic conditions and complementing recent UAV–IoT–ML integration efforts in precision farming [

17,

18,

20].

Future research will extend the current decision-support framework beyond multimodal Bayesian inference toward full cyber–physical autonomy.

First, strengthening the IoT network and system security will be essential to ensure reliable data acquisition and to protect the DSS against vulnerabilities, intrusion attempts, and manipulation of sensor streams, in line with previously proposed methodologies for IoT threat detection and prevention [

42].

Second, the framework will be advanced toward integration with robotic and mechatronic platforms, enabling autonomous monitoring, precision spraying, soil sampling, and stress mitigation using mobile and anthropomimetic robots. Prior work on safety-oriented robot operation [

43] and balance-stability control in anthropomimetic robots [

44] provides a strong foundation for incorporating robotic actuation into the DSS architecture. Additional advances in agricultural robotics, particularly in autonomous ground vehicles and UAV-enabled monitoring [

45], will further support this integration.

Ultimately, the DSS is envisioned to evolve into a secure, uncertainty-aware cyber–physical ecosystem in which Bayesian reasoning, secure IoT infrastructure, and autonomous robotics jointly support sustainable and resilient agricultural management.