1. Introduction

Citizen science is a field of study where experienced researchers involve community members to collect data for research projects [

1] as well as participate in the analysis and reporting on the project results [

2]. Public participation in scientific projects via citizen science allows community members to actively engage in resolving community problems and take charge of their environments. The objective of citizen science is to democratize science as community members learn about science and how to solve science-related problems [

3].

Within the context of developing countries, citizen science aims to foster collaboration by bringing scientists and members of the public together to find solutions to local challenges. Additionally, researchers collaborate with community members in citizen science projects to increase and expand the impact of research. As one of the eight priorities to advance open science [

4] (OSPP-REC, 2018), citizen science data plays a role in the advancement of research to strengthen and develop communities. In its nature, open science promotes open and accessible knowledge and emphasises sharing through collaboration [

5]. At the centre of sharing and collaboration lie scientific knowledge, dialogues with knowledge systems, open infrastructures and engagement with society, which form key elements of open science practices [

6].

Citizen science projects and activities have been widely reported [

7]. To make citizen science activities and projects thrive and achieve maximum impact, support and collaboration from various stakeholders for long-term sustainability are needed. As [

8] suggest, researchers, libraries, and the public should collaborate to ensure adequate retention of citizen science data. This collaboration is essential as an ongoing dialogue among all stakeholders, including academia-industry collaborations [

9]. Academic librarians are crucial to support education, research, and engaged scholarship. Aligned with advancing the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) of the United Nations, academic libraries, as key information and knowledge hubs, could provide information, systems, research expertise, and infrastructure to support citizen science activities. Therefore, academic librarians could foster collaboration among stakeholders and promote awareness and advocacy for citizen science activities to fulfil this mission.

Despite the prominent role of academic librarians in research support, the lack of awareness and expertise in citizen science and adequate resourcing of citizen science activities in academic libraries present a significant challenge [

10]. When failing to address this, academic libraries risk missing an opportunity to demonstrate their value and relevance to society at large. To ensure advanced support and assistance from academic librarians to expand citizen science opportunities and impact on societies, this paper aims to examine opportunities that will foster collaboration between stakeholders towards achieving Sustainable Development Goals outcomes. The study is guided by the objective ‘to examine ways in which academic librarians can collaborate to advance citizen science activities.’ The research question aims to provide structure in obtaining insight into the research questions:

What platforms are in place that create awareness and encourage citizen science discourse in academic libraries in South Africa?

How could South African academic libraries collaborate to support and promote citizen science?

2. Theoretical Background

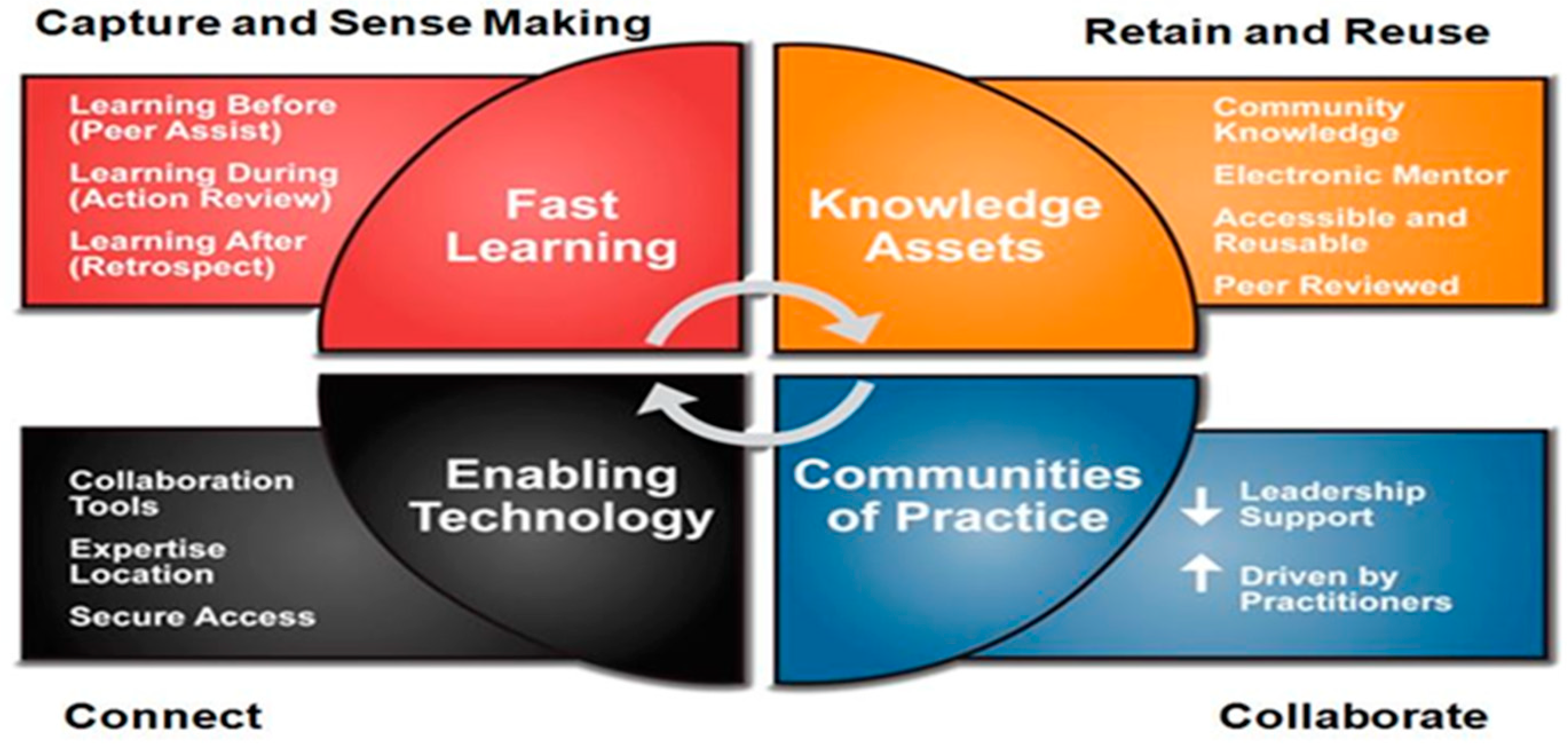

The study employed the Knowledge Management framework in

Figure 1 as a theoretical underpinning, examining collaborative platforms that facilitate awareness creation and stakeholder collaboration. The Knowledge Management framework identifies components such as capture and learn, retain and reuse, enabling technology, and collaboration as important for an effective organisation [

11]. The first component of capture and learn highlights that people can acquire and apply knowledge to finish tasks if they participate in learning processes [

11]. People can further demonstrate understanding at any point in the learning experience. The component on retention and re-using knowledge assets emphasises the point that citizen science data are knowledge assets which should be retained for future use [

11]. Guidelines should therefore be developed to ensure that these knowledge assets are open and accessible in various formats. The third component supports the notion that technology is crucial in citizen science activities as it assists citizen scientists to “connect, collect and collaborate”. The final component highlights the importance of stakeholder collaboration to ensure the sustainability of citizen science activities [

11].

Although the framework contains four components, the study applied only the “collaborate” component, which is relevant to the study’s objective of examining ways in which academic librarians can collaborate to advance citizen science activities. The following themes: platforms for creating awareness, collaborating for sustainable service, discussion platforms, key stakeholders and encouraging discussions among stakeholders, which are further discussed in

Section 4.3 under data analysis emanated from the component of collaboration. In the framework, the communities of practice are viewed as spaces for stakeholders to collaborate and achieve a common goal. This is in line with the assertion by [

8] that the success of citizen science projects relies on stakeholder collaboration.

3. Literature Review

Academic libraries play a crucial role in supporting citizen science by extending their research data services, as [

5] suggests. These libraries are the core of the universities they serve and have the potential to become hubs for citizen science initiatives. Their existing collaborations and expertise position them as valuable partners in advancing open science practices. In addition, academic libraries offer a unique avenue for fostering partnerships and engagement, particularly among students, community members and researchers, to support and advance outcomes related to SDGs. Their extensive collections provide a wealth of information that is indispensable for research projects in various fields [

12].

Traditionally, libraries have formed consortia to facilitate resource sharing and bulk procurement of information resources [

13]. However, recent changes in research have shifted the focus to collaborative efforts in research data management and preservation. For instance, the University College London Library leveraged technology by introducing Radio Frequency Identification Devices (RFIDs) to improve service efficiency. They also established open-access initiatives, creating spaces for students and researchers to engage in research-related discussions [

14].

Considering the data-intensive nature of citizen science projects, extensive partnerships are necessary to expand research related to the achievement of SDGs [

15]. The data generated from these projects is primary data as it is collected by community members. Community members could therefore contribute to SDGs through their involvement in citizen science projects. In studies conducted on the use of citizen science data to support sustainable development goals in 44 citizen science projects in the sub-Saharan Africa region and, it was established that there is potential to use this data to track the achievement of Sustainable Development Goals, albeit raised concerns of data quality [

16].

Collaboration is therefore vital to share best practices and learning from each other. As a key component of the information sharing environment, academic librarians can utilise existing relationships to promote citizen science activities, as exemplified by the collaboration between Purdue University, Aalto University Libraries and Council on Library and Information Resources [

17].

The collaboration saw a move towards promoting open geoscience content and how to promote platforms and repositories to citizen science stakeholders in Finnish university libraries. The involvement of academic librarians in such collaborative efforts highlights their significance in supporting inclusive and participatory research. This positions academic librarians as not only hubs of knowledge but also potential hubs of citizen science through fostering access to information and providing research infrastructure. Through platforms like Scistarter and Zooniverse, academic librarians can create spaces to support citizen science projects and activities [

18]. For instance, Scistarter hosts more than 3000 registered projects, allowing people to participate actively in science initiatives [

2]. Zooniverse is the world’s largest platform where citizens connect with researchers to conduct scientific research [

19]. These platforms contain large databases of projects, encourage collaboration and afford community members an opportunity to choose projects to participate in or contribute towards.

In addition to hosting information on registered citizen science projects, academic librarians can create ‘Libraries as Community Hubs for Citizen Science’ initiatives. The partnership between Scistarter, researchers, librarians, citizen scientists, and staff at Arizona State University is an example of such citizen science hubs. The creation of libraries and community hubs to advance citizen science demonstrates the potential of libraries to support citizen science [

8]. Outputs from such activities include the publication of librarians’ guides to citizen science aimed at providing insight into incorporating citizen science into library services [

20].

Virtual platforms, such as webinars, webcasts, and virtual chat sessions, can also be used to advance citizen science collaborations [

20]. Additionally, conference attendance and workshops offered by academic libraries or marketed via academic library social media may emphasise continuous professional development necessary to stay abreast of ways in which to optimally use citizen science to advance open access research.

Open access is a critical part of the open science movement advocated by academic libraries, as it allows researchers to use, re-use and disseminate their research. This fundamental role necessitates a shift in academic libraries to accommodate transformations occurring within research and information technology [

21]. The Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) recognises that libraries need to modify their services to support open preservation, dissemination and curation of published digital scientific materials [

22].

The open science movement champions open research, enabling collaborative and knowledge-exchange opportunities among diverse stakeholders such as libraries, IT departments, funders, businesses and researchers [

23]. One of the critical priorities and emerging success metrics for open science identified by the European Commission is citizen science [

4]. The inclusion of citizen science among these priorities indicates the important role played by citizen science in the domain of open science and research.

5. Discussion

Academic librarians participate in community engagement activities and regard collaborations formed through citizen science associations and communities of practice as important to sustain citizen science activities (see Knowledge Management Framework in

Figure 1). These findings view academic librarians as actively playing a facilitation role in citizen science activities, which aligns with the prescripts of the Knowledge Management Framework of seeing practitioners as driving the collaboration. At the centre of these collaborations and continuous dialogue with citizen scientists, researchers, and academics is the shared goal of the success of citizen science. Academic librarians play an important role in encouraging discussions on citizen science, creating awareness and educating stakeholders about citizen science. This extends the role of academic librarians from providing access to that of education advocacy for citizen science activities.

During the analysis, creating awareness of citizen science activities emerged as a recurring theme under the collaboration objective. In particular, the importance of initiating awareness of citizen science activities at the university level is underscored [

8]. Universities and research institutions are encouraged to play a central role in providing resources and promoting the infrastructure necessary to support citizen science initiatives. Academic libraries, which are integral components of these institutions, are expected to align their mandates with those of their institutions. According to [

39], academic librarians must have the essential skills and knowledge and the ability to develop awareness services and establish partnerships to create new services.

However, an intriguing contradiction surfaces when examining this focus on creating awareness within the context of citizen science. At the heart of citizen science lies the principle of community outreach, wherein community members actively contribute their time and expertise to citizen science projects [

9]. In essence, citizen science embodies a form of community outreach, and its success hinges on the active participation of the community. This contradiction highlights the need to balance creating awareness and fostering active community engagement, as these aspects are essential in citizen science. In the pursuit of encouraging awareness, it is crucial not to undermine the core principles of citizen science, which revolve around the invaluable contributions of community members.

6. Conclusions

Citizen science is inherently collaborative, involving multiple stakeholders, such as the community, researchers, and other interested parties, depending on the specific project. International citizen science associations have shown that collaboration is fundamental to establishing a foundation for successful citizen science activities. The study’s results also underscore the need for collaboration among citizen science stakeholders. However, there are differing views on who should take the lead in spearheading these collaborative efforts. The study recommends that academic librarians play a central role in initiating and coordinating collaboration among the stakeholders mentioned, including academic librarians, academic staff members, and community members. This recommendation is grounded in the fact that the proposal to position citizen science in academic libraries falls within the purview of academic librarians. Given their involvement in research and data-intensive environments and their existing connections with academic staff members, it is natural for academic librarians to serve as coordinators of citizen science activities.

The study also highlights the importance of using collaboration platforms, virtual or physical, to promote awareness and advocacy of citizen science. To facilitate this, the recommendation is to form a community of practice that includes academic librarians, community members, academic staff, and researchers. This community of practice will serve as a hub for collaborative efforts in citizen science. Furthermore, academic librarians should establish their community of practice to connect with local and international colleagues who have embarked on similar initiatives. This networking will enable benchmarking and the sharing of lessons learnt from peers. In addition to forming partnerships and collaborations, academic librarians should actively engage with local citizen science associations. Staying informed about new citizen science projects and actively participating in these initiatives is essential. This proactive approach will help academic librarians play a pivotal role in the advancement of citizen science within their institutions and the broader community.