A New Conceptual Framework and Approach to Decision Making in Public Policy

Abstract

:1. Introduction

Background

2. Methods

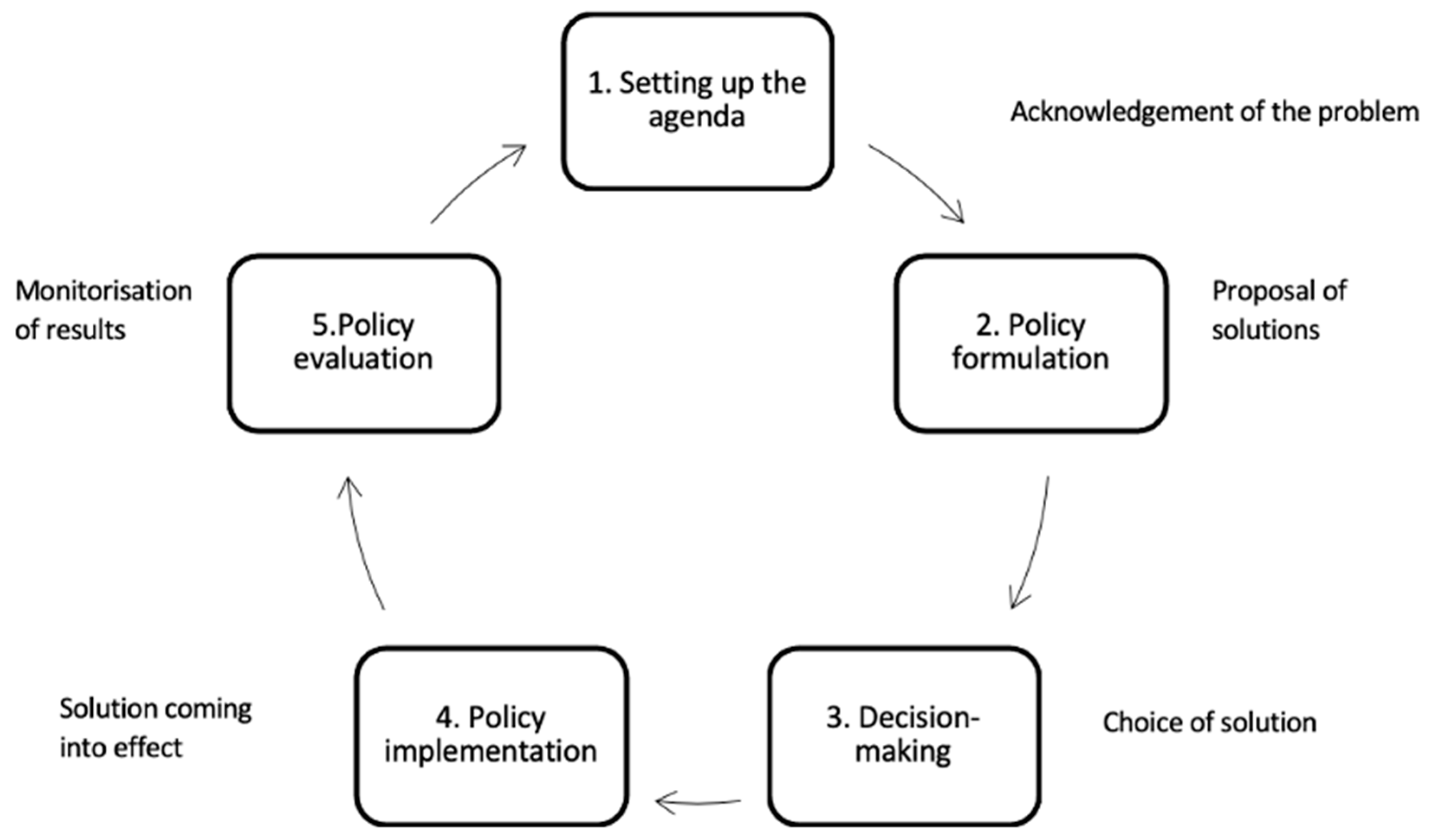

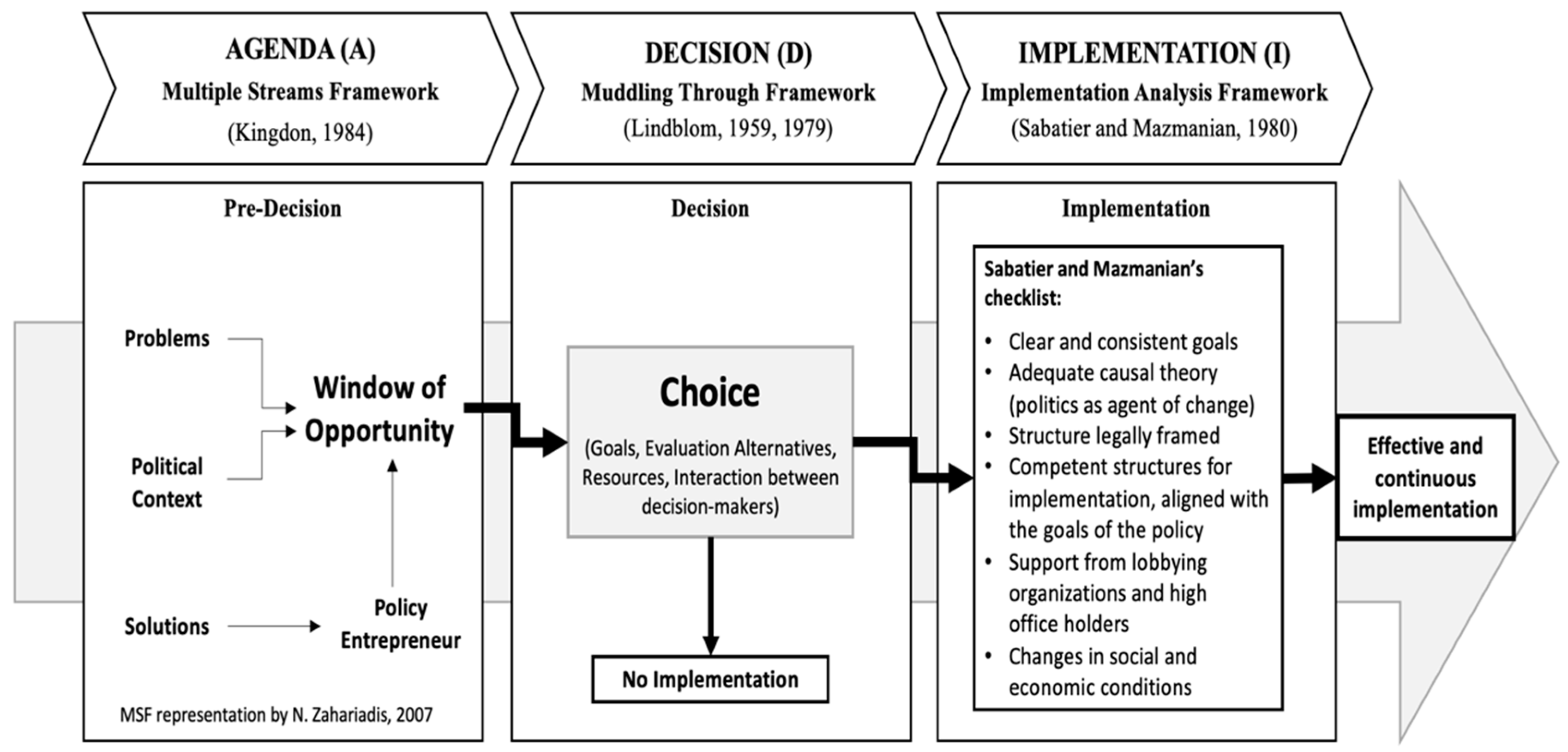

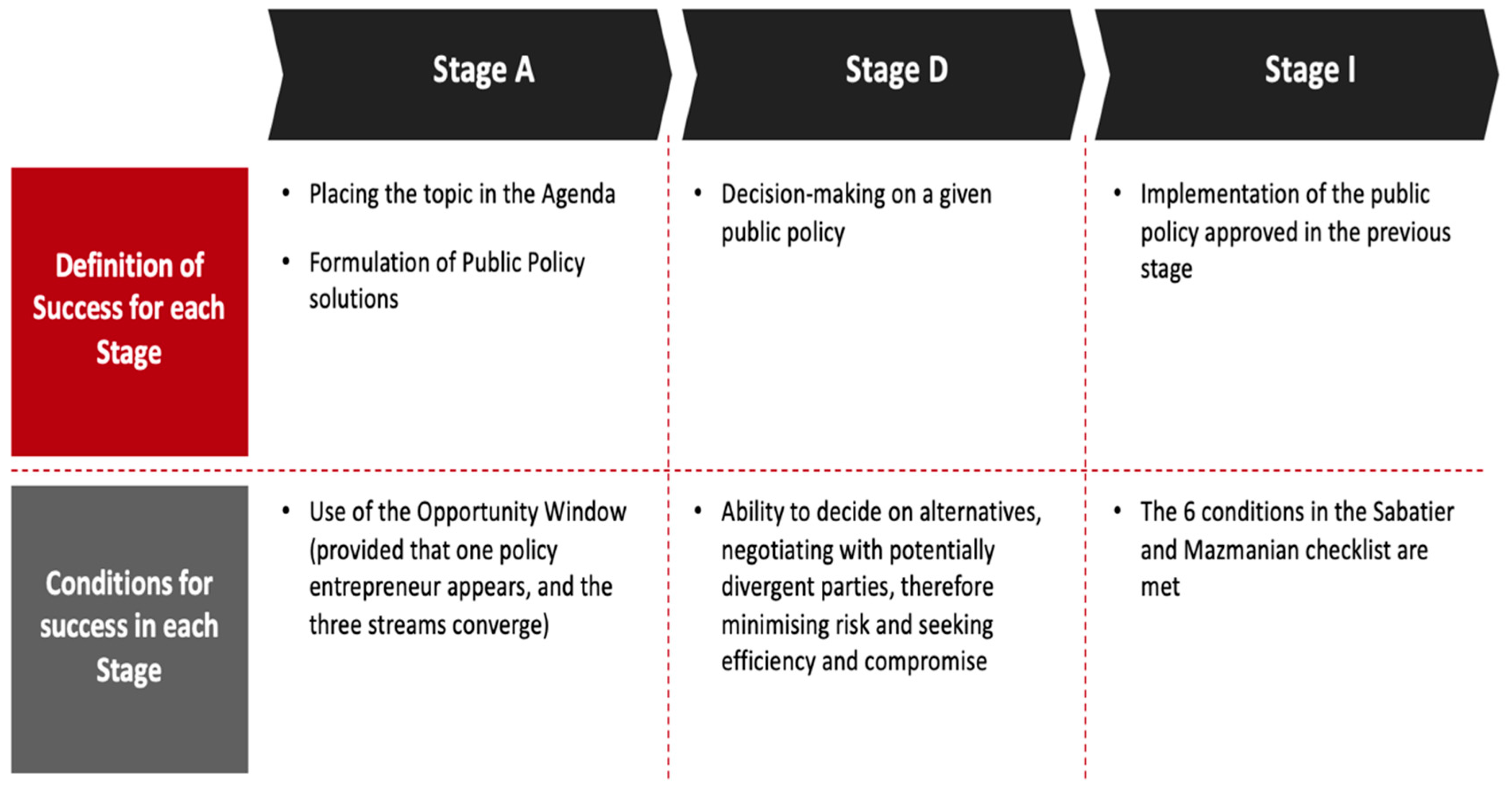

- Agenda—comprising the two first steps of the public policy cycle, as described in Figure 1 (“Setting the Agenda” and “Policy Formulation”), corresponding to a predecisional stage;

- Decision—which, as the name suggests, corresponds to the third step of the public policy cycle, “Decision-Making”;

- Implementation—the fourth step of the public policy cycle, “Policy Implementation”.

2.1. Selection Criteria

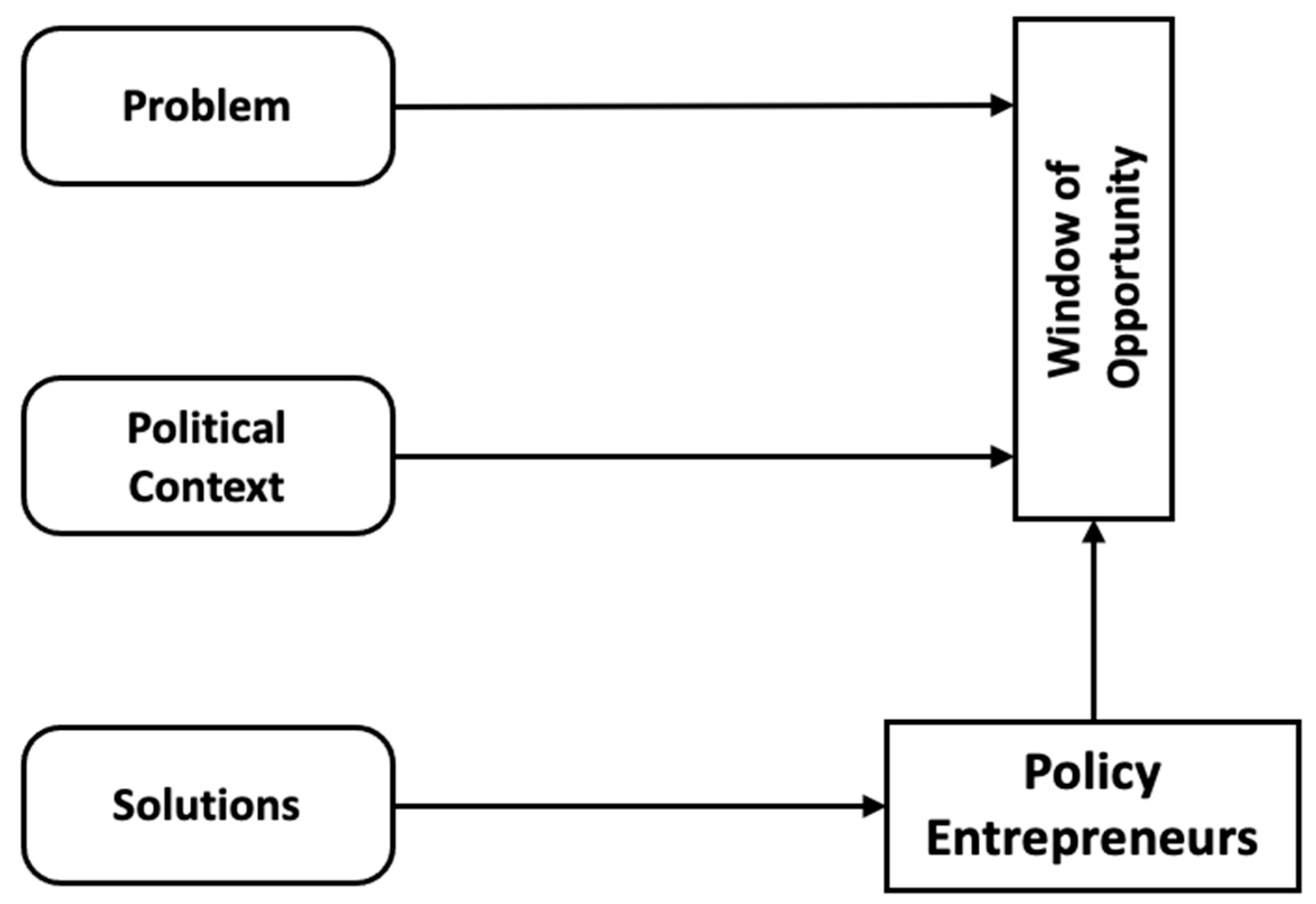

- The Agenda Stage (A)—Multiple Streams Framework (based on Kingdon, 1984);

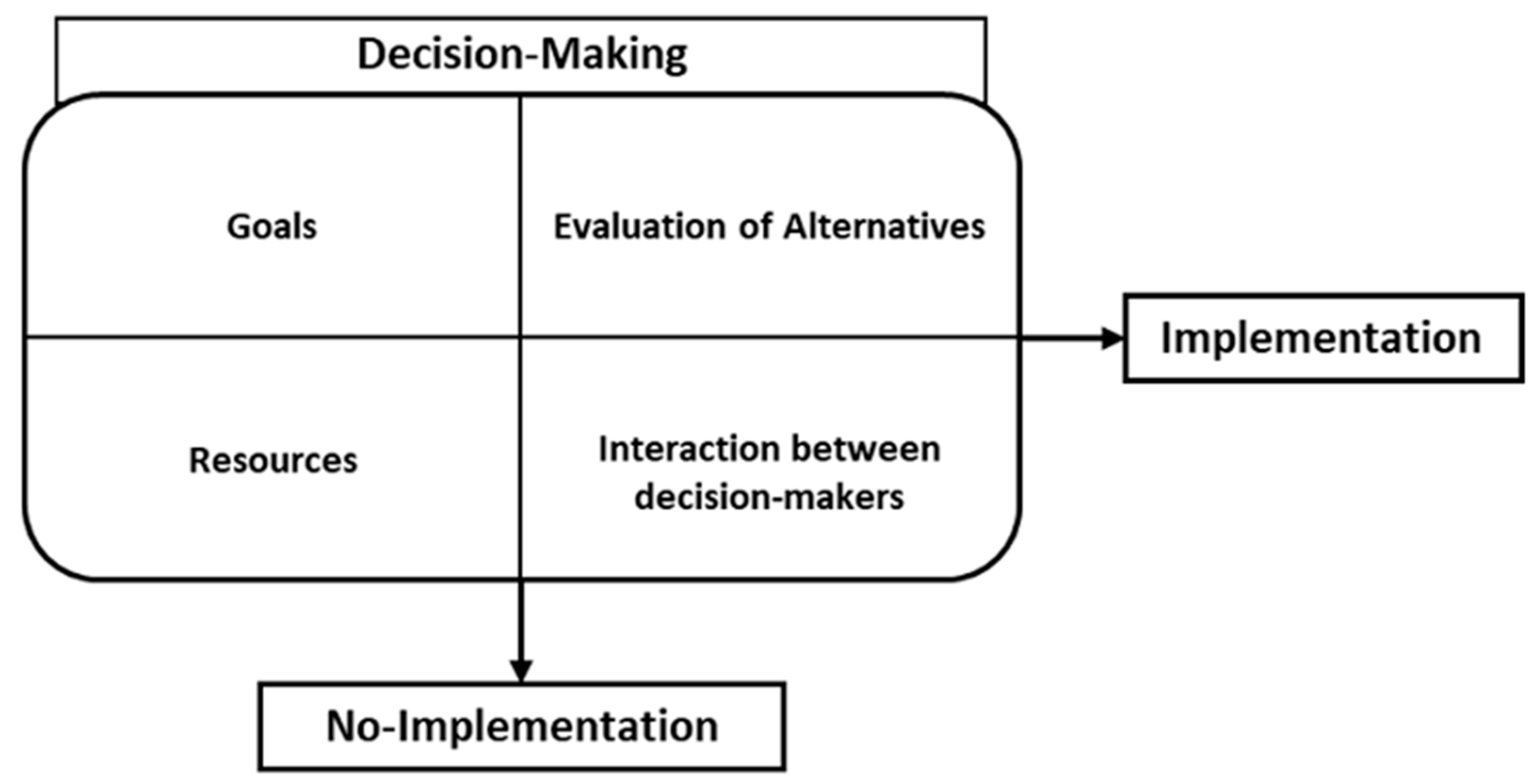

- The Decision Stage (B)—Muddling Through Framework (based on Lindblom, 1959 and 1979);

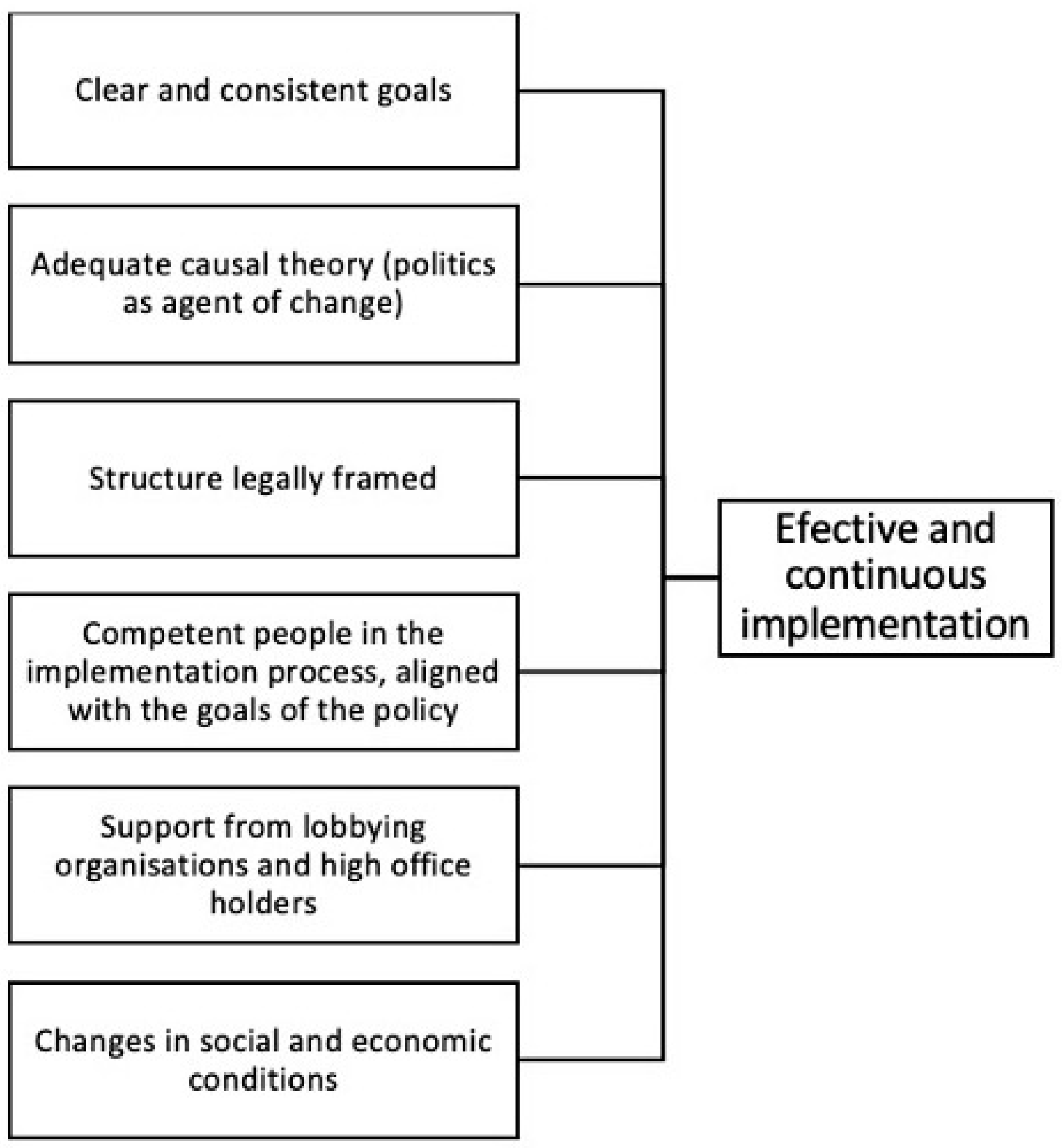

- The Implementation Stage (C)—Implementation Analysis Framework (based on Sabatier and Mazmanian, 1980).

2.2. Theoretical References Adopted for Each Stage

3. Results

Constitutive Elements of the Adopted Conceptual Model

4. Discussion

4.1. Implications for Theory

4.2. Limitations

4.3. Recommendations for Further Research

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Cejudo, G.M.; Michel, L.C. Instruments for Policy Integration: How Policy Mixes Work Together. Orig. Res. 2021, 11, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lasswell, H.D. The Decision Process: Seven Categories of Functional Analysis; Bureau of Governmental Research, University of Maryland Press: College Park, MD, USA, 1957. [Google Scholar]

- Sousa, F.; Mendes, P.E.; Freitas, J.G.; Ferreira, D.; Rocha, R.; Tavares, A. Dicionário de Ciência Política e Relações Internacionais; Almedina: Coimbra, Portugal, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Howlett, M.; Ramesh, M.; Perl, A. Políticas Públicas, Seus Ciclos e Subsistemas, Uma Abordagem Integral; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Estevez, A.; Esper, S.C. Las Políticas Públicas Cognitivasel Enfoque De Las Coaliciones Defensoras; Documentos de Trabajo del Centro de Investigaciones en Administración Pública: Buenos Aires, Argentina, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Banha, F. Implementação de Programas de Educação Para o Empreendedorismo: Processos de Decisão no Caso Português. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Algarve, Faro, Portugal, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Harguindéguy, J.B. Análisis de Políticas Públicas; Editorial Tecnos: Madrid, Spain, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Sjöblom, G. Problemi e Soluzioni in Política. Riv. Ital. Sci. Política 1984, 14, 41–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heidemann, F.G.; Salm, F.J. Políticas Públicas e Desenvolvimento: Bases Epistemológicas e Modelos de Análise; Capa Comum: São Paulo, Brazil, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Jones, C.O. An Introdution to the Study of Public Policy; Brooks Cole Publishing: Monterey, CA, USA, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Gilardi, F.; Charles, R.S.; Wüest, B. Policy Diffusion: The Issue-Definition Stage. Am. J. Political Sci. 2020, 65, 21–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davies, S.E.; True, J. Norm Entrepreneurship in Foreign Policy: William Hague and the Prevention of Sexual Violence in Conflict. Foreign Policy Anal. 2017, 13, 701–721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zahariadis, N. To Sell or Not to Sell? Telecommunications Policy in Britain and France. J. Public Policy 1992, 12, 355–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herweg, N.; Christian, H.; Zohlnhofer, R. Straightening the three streams: Theorising extensions of the Multiple Streams Framework. Eur. J. Political Res. 2015, 54, 435–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fischer, F.; Miller, G.J.; Sidney, M.S. Handbook of Public Policy Analysis: Theory, Politics, and Methods; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- O’Toole, L.J. Interorganizational Relations in Implementation: Handbook of Public Administration; Sage Publications: London, UK, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Hill, M.; Hupe, P. Implementing Public Policy: An Introduction to the Study of Operational Governance; Sage: London, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Lipsky, M. Street-Level Bureaucracy; Russell Sage Foundation: New York, NY, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Sowa, J.E.; Selden, S.C. Administrative Discretion and Active Representation: An Expansion of the Theory of Representative Bureaucracy. Public Adm. Rev. 2003, 63, 700–710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dye, T.R. Understanding Public Policy, 15th ed.; Pearson: New York, NY, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Winkler, S.C. Conceptual Politics in Practice: How Soft Power Changed the World. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Stockholm Sweden, Stockholm, Sweden, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Mintom, M.; True, J. COVID-19 as a policy window: Policy entrepreneurs responding to violence against women. Policy Soc. 2022, 41, 143–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoefer, R. The Multiple Streams Framework: Understanding and Applying the Problems, Policies, and Politics Approach. J. Policy Pract. Res. 2022, 3, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gestel, N.; Denis, J.-L.; Ferlie, E.; McDermott, A.M. Explaining the Policy Process Underpinning Public Sector Reform: The Role of Ideas, Institutions, and Timing. Perspect. Public Manag. Gov. 2018, 1, 87–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaughn, J.; Hanna, J.C.; George, W. Bush’s Healthy Forests: Reframing the Environmental Debate. Environ. Hist. 2006, 11, 868–869. [Google Scholar]

- Birkland, T.A. After Disaster: Agenda Setting, Public Policy, and Focusing Events; Georgetown University Press: Washington, DC, USA, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen, M.; March, J.; Olsen, J. “A Garbage Can Model of Organization Choice”. Adm. Sci. Q. 1972, 17, 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kingdon, J.W. Agendas, Alternatives and Public Policies; Little Brown: Boston, MA, USA, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Capella, A. Perspectivas Teóricas sobre o Processo de Formulação de Políticas Públicas. BIB Rev. Bras. Inf. Em Ciências Sociais 2006, 61, 25–52. [Google Scholar]

- Sabatier, P.A. The Need for Better Theories. In Theories of the Policy Process; Sabatier, P.A., Ed.; Westview: Boulder, CO, USA, 2007; pp. 3–17. [Google Scholar]

- Lindblom, C.E. The Science of "Muddling Through”. Public Adm. Rev. 1959, 19, 79–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindblom, C.E. “Still muddling, not yet through”. Public Adm. Rev. 1979, 39, 517–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weick, K.E. Small wins: Redefining the scale of social problems. Am. Psychol. 1984, 39, 40–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Termeer, C.J.A.M.; Dewulf, A. A small wins framework to overcome the evaluation paradox of governing wicked problems. Policy Soc. 2019, 38, 298–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabatier, P.A.; Mazmanian, D.A. The Implementation of Public Policy: A Framework of Analysis. Policy Stud. J. 1980, 8, 538–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muller, P. Les Politiques Publiques; Presses Universitaires: Paris, France, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Zohlnhöfer, R.; Herweg, N.; Rüb, F. Theoretically Refining the Multiple Streams Framework: An introduction. Eur. J. Political Res. 2015, 54, 412–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zahariadis, N. Ambiguity and Choice in Public Policy: Political Decision Making in Modern Democracies; Georgetown University Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Bendor, J. Incrementalism: Dead Yet Flourishing. Public Adm. Rev. 2015, 75, 194–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Man, E. How Crucial is the Preparation Stage for the Success of Policy Implementation? Master’s Thesis, Erasmus University, Rotterdam, The Netherlands, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Wijnstra, C.A.M. Implementation Process in a Post-Conflict Transition. Master’s Thesis, University of Twente, Enschede, The Netherlands, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Bardin, L. Análise de Conteúdo; Edições: Lisbon, Portugal, 2018; p. 70. [Google Scholar]

- Schweizer, R. “The internationalization process of SMEs: A muddling-through process”. J. Bus. Res. 2012, 65, 745–751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kopecka, A.; Santema, S.C.; Buijs, J.A. Designerly ways of muddling through. J. Bus. Res. 2012, 65, 729–739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burström, T. Learning the Ropes: Muddling Through with Tim Wilson. Int. J. Manag. Proj. Bus. 2014, 7, 726–733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cairney, P.; Jones, M.D. Kingdon’s Multiple Streams Approach: What Is the Empirical Impact of this Universal Theory? Policy Stud. J. 2015, 44, 37–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Angervil, G. A Comprehensive Application of Kingdon’s Multiple Streams Framework: An Analysis of the Obama Administration’s No Child Left Behind Waiver Policy. Politics Policy 2021, 49, 980–1020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gontijo, A.; Maia, C. Tomada de Decisão, do Modelo Racional ao Comportamental: Uma Síntese Teórica. Cad. Pesqui. Adm. São Paulo 2004, 11, 13–30. [Google Scholar]

- Motta, P.R. Razão e Intuição: Recuperando o Ilógico na Teoria da Decisão Gerencial. Rev. Adm. Pública 1988, 22, 77–94. [Google Scholar]

- Nice, D.C. Incremental and Nonincremental Policy Responses: The States and the Railroads. Polity 1987, 20, 145–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lustick, I. Explaining the Variable Utility of Disjointed Incrementalism: Four Propositions. Am. Political Sci. Rev. 1980, 74, 342–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ross, F. Forty Years of "Muddling Through": Some Lessons for the New Institutionalism. Swiss Political Sci. Rev. 2000, 6, 31–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Souza, C. Estado da Arte da Pesquisa em Políticas Públicas. In Políticas Públicas no Brasil; Hochman, G., Arretche, M., e Marques, E., Eds.; Fiocruz: São Paulo, Brazil, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Weible, C.M.; Sabatier, P.A.; McQueen, K. Themes and Variations: Taking Stock of the Advocacy Coalition Framework. Policy Stud. J. 2009, 37, 121–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Signé, L. Policy Implementation A synthesis of the Study of Policy Implementation and the Causes of Policy Failure. Res. Pap. Policy Pap. 2017, 17, 9–26. [Google Scholar]

- Cerna, L. The Nature of Policy Change and Implementation: A Review of Different Theoretical Approaches; OECD/CERI: Paris, France, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Elmore, R.F. Instruments And Strategy In Public Policy. Rev. Policy Res. 1987, 7, 174–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Stage | Dimension | Category |

|---|---|---|

| Agenda | Streams of Problems | Indicators |

| Specific studies | ||

| Feedback on political action | ||

| Events, crises, and symbols | ||

| Policy stream (alternatives and solutions) | Community of specialists (think tank) | |

| Stream of ideas inside the community of specialists (primeval soup) | ||

| Evolutive process of maturing of solutions | ||

| Technical feasibility | ||

| Compatibility with values | ||

| Financial viability | ||

| Political receptivity | ||

| Acceptance by the community | ||

| Restrictions in the system | ||

| Policy stream | Supranational/national/regional feeling | |

| Governmental changes | ||

| Stance of the involved institutions | ||

| Organised political forces | ||

| Political entrepreneurs | Visible/invisible actors | |

| Access to decisionmakers | ||

| Resources spent | ||

| Strategies used | ||

| Window of opportunity | Opening of the window of opportunity |

| Stage | Dimension | Category |

|---|---|---|

| Decision | Goals | Connection to other problems |

| Prevalence of ambiguous goals instead of clear ones | ||

| Transversal solutions to other problems | ||

| Alternatives | Few proposals, which are more or less similar | |

| Interconnection between the evaluation of the action to accomplish and goals to achieve | ||

| Resources | Previous experiences | |

| Decision support information | ||

| Little relevance of theory | ||

| Financial situation | ||

| Interaction between decisionmakers | Decisionmakers with different visions | |

| Previous inexistence of clear goals by decisionmakers | ||

| Cultural idiosyncrasies | ||

| Leadership | ||

| Choice of solution | Trial-and-error process | |

| Increased preoccupation with problem mitigation and desirable results | ||

| Consensus as a sign of good decision |

| Stage | Dimension | Category |

|---|---|---|

| Implementation | Goals | Clear |

| Consistent | ||

| Adequate causal theory and influencing power | Involvement of public institutions/the state in the concretisation of the program | |

| Suitable delegation of powers (decision-making powers) | ||

| Legally framed structure | Allows access to institutions that support the program | |

| Suitable hierarchical integration | ||

| Possibility of assigning responsibility to specialised entities | ||

| Enough financial resources | ||

| Adequate decision-making rules | ||

| Dedicated and competent people | Commitment to the achievement of goals | |

| Training in management and political science | ||

| Support from lobbying groups and people in high positions | Formalisation of support | |

| Decision power | ||

| Changes in social and economic conditions | Economic | |

| Social |

| Models | Advantages | Disadvantages |

|---|---|---|

| “Multiple Streams Framework” (Kingdon, J., 1984) | - The MSF deals with various variables (such as the time, different groups of people involved, and subjective perceptions of events, situations, and solutions) and scenarios. It also asserts that policy making is not an inherently rational process, and thus it takes into account real-world situations (such as ambiguity and uncertainty) that influence the political agenda [23]; - The MSF gives users unparalleled flexibility: there is no need for a detailed codebook to test hypotheses or advance general policy theory. Researchers can read one book (or a couple of chapters) and generate a theoretically informed and publishable empirical case study [46]; - The MSF is considered adequate to explain the initial stages of public policy making, especially in ambiguous processes, where information is scarce and the decision is time-sensitive [28,30]; - The “barrier to entry” of the framework is low compared with other policy process approaches, such as the Institutional Analysis Framework and Development Framework [46]; - This is a very popular, well-known, and widely used framework. The high number of citations confirms this [37], as does its resurgence in papers on COVID-19 measures [23]; - Kingdon identifies what we call “universal” policy-making issues that can arise at any time or in any place [46]; - The MSF seeks to provide tools for understanding the policy-making process, rather than focusing on predicting future events [29]. | - Framework focused on the predecision stage (i.e., in the setting of the agenda and policy formulation) [37]; - Focus on case studies, and thus, qualitative analysis. This leads to very little quantitative research use [38]; - Limitative in the analysis of why the policy change fails, either due to the implementation of an agenda that fails, or the failure to achieve a majority to pass the initial proposal during the decision process [14]; - Most applications do not fully use the MSF’s problem stream, policy stream, politics stream, policy entrepreneur, or policy window concepts, nor all their subcomponents [47]. |

| “Muddling Through Framework” (Lindblom, C., 1959, 1979) | - This framework allows for an approach that is aligned with the decisionmaker’s daily life. By verifying the limitations inherent to the decision process, this framework seeks a method capable of reducing the complexity of the reality that permeates it [48], in which political actors decide through a restricted series of successive comparisons between alternatives that are marginally different from each other [31,32]; - It enables the identification of common elements in the decision strategies effectively followed by public policy decisionmakers [10]; - Faced with many participants (stakeholders) in decision making, this framework organises reality in a simple way, and it focuses on stratagems that allow for the identification of the fragmentation of the analytical work arising from the attention that decisionmakers pay to their part in the domain in which the problem under consideration is inserted [4]; - The decisions taken represent what is politically feasible, rather than what is technically desirable and what is possible [4]; - The framework integrates analytical categories and dimensions. This makes it possible to observe the elements of integration versus fragmentation that affect the processes and actions of decisionmakers [4,49]; - Given the knowledge limitations to which policymakers are subject, simplification through a narrow focus on small variations around an existing policy allows for the maximum advantage to be taken of the available knowledge [31,32]; - It is one of the most recognised frameworks, which makes it one of the most widely cited articles in the field of public administration and organizational theory [39]. | - This framework is unlikely to assume the novelty of a policy, the number of decisionmakers involved, or the degree of consensus among them on the policy-making goals [39]; - This framework is better suited to relatively stable environments than it is to situations that are uncommon, such as a crisis or new political problem [50,51]; - The possibility of a nonincremental process mediating this relationship, overriding it, or simply interacting with it in some way to modify the direct link was largely overlooked in the development of the model [52]; - The multiplicity of decision processes that have acquired the title “incremental” has deprived the concept of descriptive and explanatory value [52]. |

| “Implementation Analysis Framework” (Sabatier, P. and Mazmanian, D., 1980) | - The framework allows: (i) the explanation of the political cycle as a causal theory; (ii) the integration of top-down and bottom-up approaches; (iii) the assumption of the importance of technical-scientific knowledge in the political process [53,54]; - The framework allows an understanding of how the process of formulation—as well as the mandate that comes with it—either attracts or detracts the chance that programmes and public policies are implemented [55]; - This framework provides a clear and objective structure and defined checklist, thus enabling the kind of analysis that is not just “descriptive”, but more pragmatic [6,35]; - The model has been used to identify critical variables in the implementation processes, allowing an analysis of which factors facilitated and/or limited the effectiveness of this implementation [41]. | - Because the framework is focused on “how well” programs and policies are implemented, the substance and quality of these are underestimated [56]; - The framework tends to focus on the policymaker rather than on those affected by the policy, and it ignores the role of policy opponents, who make demands during the policy process [53]; - The original approach of the model does not provide an accurate empirical description and explanation of the interactions and problem-solving strategies of the actors involved in the policy delivery [57]. |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Banha, F.; Flores, A.; Coelho, L.S. A New Conceptual Framework and Approach to Decision Making in Public Policy. Knowledge 2022, 2, 539-556. https://doi.org/10.3390/knowledge2040032

Banha F, Flores A, Coelho LS. A New Conceptual Framework and Approach to Decision Making in Public Policy. Knowledge. 2022; 2(4):539-556. https://doi.org/10.3390/knowledge2040032

Chicago/Turabian StyleBanha, Francisco, Adão Flores, and Luís Serra Coelho. 2022. "A New Conceptual Framework and Approach to Decision Making in Public Policy" Knowledge 2, no. 4: 539-556. https://doi.org/10.3390/knowledge2040032

APA StyleBanha, F., Flores, A., & Coelho, L. S. (2022). A New Conceptual Framework and Approach to Decision Making in Public Policy. Knowledge, 2(4), 539-556. https://doi.org/10.3390/knowledge2040032