1. Introduction

Natural language processing (NLP) is a powerful tool in processing text and has been an area of intense focus in terms of research and application since the 1990s [

1,

2,

3]. However, its application is relatively new to the mining industry and mine safety. The NLP tools are capable of processing huge amounts of text in relatively quicker times when compared to human subjects. This is a huge advantage, as insights can be gained quickly and without using much human resources. The reason accident narratives are not analyzed at mine sites is because most lack the human resources necessary for the task. The insights can then be used to deploy intervention strategies. At the start of the 21st century, an application of NLP to safety data was demonstrated by the Pacific Northwest National Laboratory (PNNL). The laboratory’s team has successfully analyzed huge amounts of safety reports from the National Aeronautics and Space Administration’s (NASA) aviation safety program to gain valuable insights [

4].

Mine sites in the US are required to report details of certain types of accidents to Mine Safety and Health Administration (MSHA). In turn, MSHA maintains an accident database with concise descriptions of such reported accidents (narratives) along with other metadata [

5]. The database is a valuable resource for mine safety professionals in creating the text “corpus”, which can help in “training” the machine learning (ML) models. Classification of narratives into their respective accident types is an important step in accident analysis. In their past research, authors have demonstrated how NLP-based ML models (random forests) developed using the MSHA corpus can be used effectively on non-MSHA narratives [

6]. This was an important accomplishment, as developing NLP models on site-specific narratives are expected to be difficult for two reasons. First, a site may not have the variety in narratives that would be necessary to develop good NLP models. Second (and more importantly), however, unless a mine categorizes accidents, NLP modeling would require a human tagging of historical narratives. Tagging is when a narrative is concisely summarized in a few words. The tags essentially serve as the “meaning” of the narrative. Tagging is an expensive and limiting part of NLP. All narratives in the MSHA database are tagged on entry, thereby making the database a convenient corpus for NLP. However, until the previous work was published [

6], it was unclear if models developed on the MSHA corpus would be applicable on a non-MSHA corpus. Thus, the previous work will encourage researchers and mine sites to develop NLP models exploiting the tagged MSHA corpus, knowing that the resultant models would apply to their sites. This paper continues the work to improve the performance of the NLP models. To start with, a “caught in” accident category was chosen.

There are certain limitations that prevent the NLP-based models from achieving their full potential in terms of high prediction success. The diversity in industry-specific safety language and narrators’ individual writing styles are some examples. Moreover, the source and circumstances of an injury differ from industry to industry [

7,

8], resulting in differences in vocabulary. In this context, it can be anticipated that accident classification models developed for one industry may have varied success rates in other industries. In the same context, expert or domain-specific knowledge can be helpful in gaining a deep understanding of accident circumstances and underlying mechanisms, which in turn can help improve classification success rates. For instance, according to the US Occupational Health and Safety Administration (OSHA), “caught in between” type accidents are those that involve, typically, a person or a body part being squeezed, caught, crushed, pinched, or compressed between two or more objects [

9]. From the NLP standpoint, the actions that describe the “crushing” effect are what define a “caught in between” accident. Hence, the list of words or verbs that describe such actions (vocabulary lists) are necessary in training the NLP-based classification models. Key to success in NLP is thus finding the words that are essential to describing a particular class of narratives.

Domain-specific knowledge is highly valued and regarded as an essential tool for safety professionals working in the mining industry [

10] as well as in any other industry [

11]. This is the reason exploitation of domain-specific words and phrases, or in short form, domain knowledge elements (DKE), is common [

12]. For instance, using a semantic rule-based NLP approach, Xu et al., 2021 [

12] found DKEs that can provide valuable insights in analyzing the text in a Chinese construction safety management system. The process involves finding specific compound parts, parts-of-speech (pos) tagging, and dependency of words (DOW) that are important to understand the topic (construction safety)-specific language. The models developed in this paper leveraged such domain-specific knowledge elements.

Data preparation for ML models pose certain challenges when text handling is involved. Since the models can only operate on numbers, vectorization of words is necessary. At first, the text (or narratives) are split into unique words (unigram ‘tokens’) and then into representative “word vectors” of real numbers. The numbers signify an occurrence (1), no occurrence (0), or a number of occurrences (

n) of tokens. Bag of words (BOW) models are popular in this context. They can reduce each accident narrative into a simple vector of words and their corresponding frequency of occurrences [

13]. Due to their simplicity, these vectors take much less computer memory compared to other models. However, BOW models fail to account for the similarity or rarity of words in a narrative, which is an important aspect of classification problems. The mere list or bag of words from processing a narrative cannot convey the true meaning of a narrative. Semantic relationship of words, such as their occurrences in close proximity, context, and order, matters. For instance, the phrases “caught between rollers and fell” and “fell and caught between rollers” have the same vocabulary from a BOW model perspective, but the connotations are different. This poses a problem for classification algorithms.

The “word embedding” concept compensates for the BOW model’s shortcomings by vectorizing similar words (“features”) with similar scores [

14]. The underlying concept is that linguistic items with similar distributions or words that occur in similar contexts have similar meanings [

15]. For instance, the terms “injury”, “accident”, and “pain” are represented as being closer in vector space when compared to words such as “surface”, “path”, and “pavement”. The models can also vectorize the word frequencies in a narrative in comparison to other narratives. For instance, based on how frequently a particular word occurs in a narrative, it can be set to carry more “weight” in terms of score representation in the vector. There are several types of word embedding methods and models that are available with slightly different vectorization strategies. For instance, in order to find the relevance of a word to a particular document or block of text, a term frequency–inverse document frequency (tf-idf) method is used. Depending on how frequent (term frequency) a word occurs and how commonly (score: 0) or rarely (score: 1) the word is found in a document, tf-idf method scores the words. This is a very important tool in “text mining” and is used in search engines. Several researchers used tf-idf-based models in analyzing OSHA accident data [

16,

17]. Some models developed were generalized and even deployed to analyze mining and metal industry accident data [

17].

Word embedding models are to some extent limited by a meaning conflation deficiency. The problem stems from the representation of words that have multiple meanings in a single vector [

18]. For instance, the word “pin” as a noun represents a pin. As a verb in the phrase “pinned between two objects”, it conveys a different meaning. A “pinner” in the underground mining context, however, implies “a roof bolter”. A word represented in its true sense (“sense representation”) may be the solution for the problem. Collados et al., 2018 [

18] presented a comprehensive overview on the two major types of sense representation models in the area, that are, unsupervised and knowledge-based. The former model depends on automatic word processing by algorithms looking for different senses of a word in the given context of words. The latter depends on expert-made resources such as WordNet, Wikipedia, and so on. In this context, expert-knowledge-based word clusters are used for training the algorithms in this paper in order to classify accident types.

“Pretraining” compensates for a shortage of training data, which is one of the biggest challenges for the NLP community currently [

19]. In pretraining, models are trained on very large datasets, such as millions and billions of annotated text examples. For instance, Google’s Word2Vec is a “pretrained word embedding” technique that is trained on the Google News dataset (which consists of about 100 billion words) [

20]. Once pretrained, the models can be fine-tuned on smaller datasets [

19] to provide enhanced performance. Popular embedding techniques such as Word2Vec and GloVe perform “context-free” vector representation of words; for instance, the word “bank” in “bank account” and in “river bank” would have the same representation [

19]. To compensate for the problem, bidirectional encoder representations from transformers (BERT) was invented [

21] and has been widely popular among NLP researchers in the recent past [

22]. BERT contextually represents words and can perform the sentence processing bidirectionally (left to right, and vice versa) [

19]. Unfortunately, many advances in NLP do not apply to mine safety narratives, as the language of safety is relatively unique. Mine safety is a niche topic with nuances in the language, and therefore blanket application of generic language models can be quite misleading. Therefore, this research focused on nuances of the language of mine safety.

Ensemble learning methods use multiple algorithms to improve on their individual predictive performances. The random forest (RF) method is an example where results from multiple decision trees are used to obtain the final result [

23]. The “stacking” style approach in ensemble methods takes advantage of diverse sets of algorithms to achieve the best result for a given problem. An individual model can have better predictive strength in one area of the dataset but fare poorly on certain other areas. A separate model (stacked model) can be developed for such areas to improve overall predictive performance. Several researchers have applied the stacking methods to traffic-related problems, such as analysis of incidents, accidents, congestion, and so on [

24,

25,

26].

Random forest (RF) methods are popular among the other classification methods due to their robustness and accuracy [

23]. Several researchers have used the methods in a wide variety of areas and industrial contexts, such as construction injury prediction and narrative classification [

27,

28], flood hazard risk assessment [

29], building energy optimization and predictive climate control [

30], predicting one-day mortality rate in hospitals [

31], and crime count forecasting using Twitter and taxi data [

32]. The accuracy and performance of RF methods has been found to be superior when compared to other ML methods by several researchers [

28,

33]. For instance, in classifying unstructured construction data, Goh and Ubeynarayana, 2017 [

28], used and compared the performance of various ML methods such as logistic regression (LR), k-nearest neighbors (k-NN), support vector machines (SVM), naïve Bayes (NB), decision tree (DT), and RF. In finding the factors affecting unsafe behaviors, Goh et al., 2018 [

33] used and compared the performance of various ML methods such as k-NN, DT, NB, SVM, LR, and RF. In both the cases, RF showed superior performance. Due to this reason, it was the method of choice for the accident narrative classification done in previous research by the authors in Ganguli et al., 2021 [

6]. In the current work, novel models were developed to be “stacked” with RF models (to improve the performance) previously developed in Ganguli et al., 2021 [

6].

From the literature review, it can be observed that although the NLP-based ML models are swift in auto-processing huge amounts of text, they have limitations in achieving high success rates. This is due to the diversity in industry-specific safety-related vocabulary. A certain level of human (expert) intervention is required in fine tuning or better training these algorithms. Due to this reason, in the PNNL case, linguistic rules developed by human experts were used for modeling. The linguistic rules developed considered specific phrases and sentence structures common in aviation reports. When used in modeling, these rules were able to automatically identify causes of safety incidents at a level comparable to human experts. The PNNL team, however, noted the reliance of the algorithms on human experts with domain-specific knowledge [

4]. When classification challenges occur where traditional or learned approaches fail, application of heuristic methods is not uncommon [

34,

35]. For instance, in identifying the accident causes in aviation safety reports, Abedin et al., 2010 [

34] used a simple heuristic approach in labeling the reports. The approach looks for certain words and phrases that are acquired during the semantic lexicon learning process in the reports. Using ontology as a key component, Sanchez-Pi et al., 2014 [

35] developed a heuristic algorithm for automatic detection of accidents from unstructured texts (accident reports) in the oil industry. ASECV draws inspiration from such heuristic approaches.

Hence, the novelty of the research presented in this paper lies in developing models to: (i) resolve the ambiguity in the classification problem, that is, one narrative classified into multiple accident categories (addressed by the SS model); (ii) save process time and memory, and reduce the large size of the training set vocabulary by utilizing industry (mining)-specific expert knowledge and heuristics (addressed by ASECV model); and (iii) improve RF method performance from past research by “stacking” with the best of SS and ASECV models (stacking approach).

2. Previous Research and Importance of This Paper

An important practical application of this research would be in the development of automated safety dashboards at mine sites. In this context, a dashboard is a collection of visual displays of important safety metrics and key performance indicators (KPI) in real time. Currently, the safety dashboards used by mine management simply report on injuries, rather than the causes. This is because of the fact that narratives are not analyzed in a holistic manner, as most mine sites lack manpower that is skilled in analytics. Automatic classification of safety narratives would allow causation (accident type or category “tag”) to be included in the dashboards. For example, in addition to listing the number of back sprains, if the dashboard also includes causation tagging, such as “overexertion due to lifting” or “overexertion due to pulling”, mine management could deploy more meaningful interventions to improve overall workers’ safety. Thus, in the context of mine safety research, the work presented in the paper is novel and very helpful to academic researchers in the area as well.

In the previous research, nine separate RF-based classification models were developed for nine corresponding accident categories; which are explained in detail in

Section 3.2. The models were trained (50:50 train-to-test split) based on the narratives in the MSHA database [

6]. The trained models were first tested on narratives in the MSHA database, then on narratives in a non-MSHA (partner mine’s) database. After the testing, it was found that the MSHA-based RF models were extremely successful in classifying the non-MSHA narratives (96% accuracy across the board). While this is a welcome development, several challenges were encountered. Since nine RF models were deployed separately (standalone), it resulted in certain narratives being classified into multiple accident categories instead of one narrative into one category (which is desirable). According to MSHA criteria, a narrative is generally classified into one category that best describes it. In addition, certain narrow categories, being special cases of (or closely related to) other categories, posed multiple classification problem. For instance, a narrative can be classified as “caught in, under or between a moving and a stationary object” or CIMS, as well as “caught in”, since the former is a special case of the latter. Due to their shared vocabulary, certain narratives were also classified into two very different categories, such as “caught in” and “stuck by”. To resolve such classification overlaps and tag a narrative with only one accident category, a “similarity score” (SS) approach was used in past research. This method is explained in detail in

Section 3.3, in the description of methodology.

In this context, the aim of the current work presented in this paper is to resolve the challenges present in the past research. This is accomplished by turning the SS approach in the previous work into an “SS model” and devising new models to experiment to improve upon the previous success rates of RF models. For the current work, however, non-MSHA narratives were not used; only MSHA narratives were used. Due to the complexity of the problem and the presence of multiple classes in RF-based classification in previous work, the authors aimed to start the experimentation with a sizable portion (with a subcategory such as “caught in”). If it achieved success in this category, the intent was to extend the scope of strategies and methodology to all other categories in future work. Hence, the goal of the current research is to improve the classification performance in the category “caught in”, while other categories are considered out of scope.

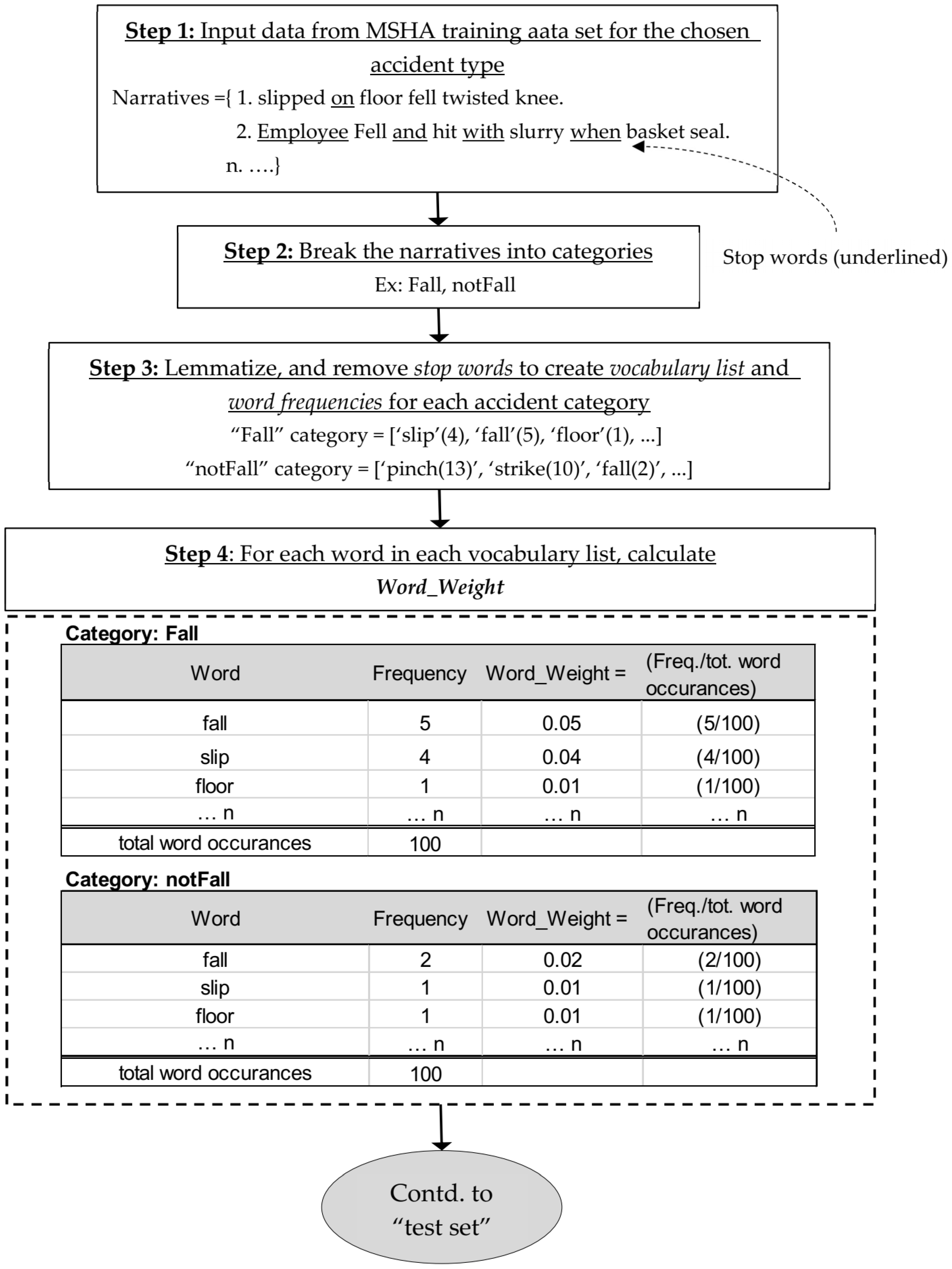

The concept behind the SS model can be described briefly as follows. Words in each narrative in the modeling or training set were weighted (scored) based on the frequency of their occurrence within an accident category. Thus, the same word is “weighted” differently by different accident categories. From the training set narratives, the SS model builds vocabulary lists for each accident category. Each word or token in a vocabulary list has a set of “weights” corresponding to an accident type. During the application of the model to the test set, each narrative is scored based on the word weights obtained from the training set (accident specific vocabulary weights). This means that a narrative has a score specific to each accident type. Ultimately, a narrative will be assigned to the accident category where it scored the highest when compared to other categories [

6]. In this way, the SS method is a unique tool in predicting and assigning a narrative to its most relevant category. Hence, the concept was used in building a new classification model (“SS model”) in an attempt to improve the overall success rates of RF models on the MSHA dataset. As opposed to SS approach used in past research—as an additional tool on RF results—the current work uses the SS model as a standalone classification tool.

One challenge for the SS model is that, in order to assign weight scores to words in a given narrative, thousands of narratives need to be processed to form the training set. For instance, there are 4563 narratives that belong to the “caught in” category in the MSHA training set of 40,649 narratives. After text processing and lemmatization, there are 4894 unique words derived out of the 4563 narratives in the category. This paper explores whether a smaller group of words or phrases selected using expert knowledge can be used to detect the “caught in” category or if all of 4894 words need to be used. In this context, a “word-clusters”-based model was developed. It is a heuristic model, using certain expert choice (authors being experts in the mining discipline) vocabulary clusters, and is named as “accident specific expert choice vocabulary” (ASECV). A goal for the model was to keep the false positive rate under 5% to improve its robustness. Finally, as a third (and important) approach, the models (ASECV or SS) were “stacked” on the previous RF models to improve upon the overall success rates. Stacking can be performed in variety of ways. The stacking option chosen for this paper is explained in detail in the methodology outlined in

Section 3.5.

Although the RF method alone is not the focus of the current work, it is included in the methodology described in

Section 3.2. in order to provide proper background on the past research. As part of the SS and ASECV methods, several experiments (iterations) were conducted to progressively minimize the false positive rates of the models, thus improving the prediction performance. The experimental (iteration) parameters with low false positive rates are ultimately selected for use in stacking method. Thus, it should be understood that the aim of the research is to improve the performance of the RF model (from past research) by the novel approaches, but not solely to compare and contrast the novel models with the RF method.

4. Results

The results from each of the three approaches and their corresponding experiments are described in the following sections. The aim of the experiments was to find high-performance model parameters between the SS and ASECV methods so that the parameters can be used when the stacking approach is deployed.

4.1. Results: SS Model

The “vocabulary strategy” column of

Table 6 shows the type of strategy followed for SS model training exercises to create the accident-specific “vocabulary sets”. As stated in the previous sections, these vocabulary sets will be used to score and classify test set narratives. The “SS Criteria” column provides targeted accident categories for narrative classification. In order to compare with RF results from past work, the CIMS accident category was chosen. The aim is to find the combination of vocabulary strategy and criteria at which the SS model provides the best performance in terms of high “Success within (accident) category” with low “false positive rates”. The aspiration is that if the results from SS modeling for the CIMS category outperform the RF model, the criteria can be extended (and applied) to other accident categories to get the similar results. It should be noted that all the results presented in this section are obtained by applying the strategies on test set narratives. The following are some dataset parameters used.

Total “test set” samples (n_samples) used = 40,649;

Total samples in target category (n_target) = 3310;

Total samples in other categories (n_other) =37,339.

Table 6.

RF vs. SS: Classification performance for CIMS type accidents.

Table 6.

RF vs. SS: Classification performance for CIMS type accidents.

| | | | Target Category Predicted Accurately (n_target_accurate) | Success within Category: n_target_accurate/n_target | False Positive Rate: false_predicts/n_other |

|---|

| | Vocabulary Strategy | SS Criteria | RF | SS | RF | SS | RF | SS |

|---|

| 1 | All words | Multiple Catg. (9) Splitting | 1815 | 290 | 55% | 8.8% | 2% | 15% |

| 2 | All words | Few Catg. (FWW/CIMS/SFO/Other) Splitting | 1815 | 170 | 55% | 5.1% | 2% | 12% |

| 3 | Excl. words (100) | Few Catg. (FWW/CIMS/SFO) Splitting | 1815 | 3005 | 55% | 90.8% | 2% | 24% |

| 4 | Excl. words + 25freq. Words | CIMS, notCIMS, Neither Class | 1815 | 3305 | 55% | 99.8% | 2% | 96% |

| 5 | Excl. words + 25freq.+ Adj. Wts. | CIMS, notCIMS, Neither Class | 1815 | 3208 | 55% | 96.9% | 2% | 58% |

| 6 | Excl. words + Diff. qualify strategy | CIMS, notCIMS, Neither Class | 1815 | 159 | 55% | 4.8% | 2% | 58% |

At first, all words in their respective vocabulary sets for nine accident categories were tried in narrative classification (Strategy 1). The success rate was poor (8.8%) compared to RF (55%), and the false positive rate was high, at 15%, when compared to RF’s 2%. In strategy 2, the number of accident categories was minimized (FWW, CIMS, SFO, and other) to observe if it can help improve the performance. The “other” category includes all narratives in the training set outside of the three categories noted. FWW, CIMS, and SFO are very narrow categories, as opposed to the rest of the categories such as “caught in” or “struck by” demonstrated in the RF model (

Table 2). The success and false positive rates for Strategy 2 went slightly down to 5.1% and 12%, respectively, when compared to Strategy 1.

Even though common words such as “employee” and “EE” were eliminated as part of the stop words, it was observed that all accident categories share vocabulary to a certain extent. For instance, the tokens “pain”, “hurt”, and “fall” are common in each accident type. This could be one reason that Strategies 1 and 2 registered such low success rates to begin with. This prompted a change of strategy to eliminate such common vocabulary among all accident categories. Therefore, Strategies 3–7 include only “exclusive” vocabulary sets for each accident category. With the new strategy, it was hoped that the SS score of a narrative would be high for a particular accident type when its exclusive vocabulary was present in the narrative. As an experiment, for Strategy 3, the top 100 most frequent words of the vocabulary list were used. The success rates for CIMS improved significantly (90.8%), but with increased false positive rates (24%), which is not desirable.

At this stage, it can also be noticed that the CIMS category performance depended upon how well the narratives are split between several other categories. Similar to the RF models developed in the past research, one model to classify one category avoids such dependencies. Moreover, there will only be two major vocabulary sets at any given point of time, which is less complex for modeling. A CIMS category classification model, for instance, will have two vocabulary sets from training, that is, all vocabulary that belongs to CIMS and the rest of the vocabulary (“notCIMS”). In the testing process, when the SS scores of a narrative for CIMS and notCIMS become equal, it sometimes creates ambiguity for the algorithm. In such cases, the narrative will be classified into “Neither Class”, which is counted in the notCIMS category for calculation purposes. For Strategies 4 and 5, all exclusive words along with the 25 most frequent “common” words were used. Although the success rates were high (>95%), the false positive rates were high as well (96% and 58%, respectively), which is not desirable. The high false positive rates are due to the presence of words, patterns, or certain elements from multiple accident categories in one narrative. For instance, the narrative “employee fell and caught his hand between the moving conveyor belt and stationary guard” can be classified by MSHA as a “Fall” accident. However, models or algorithms can interpret and classify the same narrative in a few different ways. For instance, due to the presence of words “caught” and “in between”, it can be classified in the “caught in” category or the “caught in between moving or stationary objects” category due to the presence of objects such as “conveyor belt”, a moving object, and a “guard”, a stationary object.

Contrary to other strategies, it should be noted that for Strategy 5, the weights of words in vocabulary lists are adjusted proportionately to the 25 most frequent words. For Strategy 6, all exclusive words were used along with a “difference” strategy. The strategy can be explained as follows. For the training set, it is possible that the difference between the CIMS and notCIMS scores for the narratives can have a correlation with accurate prediction (CIMS) rates. In particular, a score above the 95th percentile of the “difference” was observed to be highly correlated with correct prediction of the accident type. This is used as a “qualifying criteria” for Strategy 6. In the test set, whenever the difference between the scores for a narrative “qualifies”, it will be automatically categorized as CIMS. The strategy, however, has limited success (4.8%), with high false positive rates (58%).

Overall, the strategies yielded mixed results, with success rates varying between 4.8% to 96.9%, and false positive rates between 12% to 96%. Since the false positive rates are higher than the desired levels (<5%), the SS model is not considered suitable for stacking over the RF model.

From the SS model results, it is observed that improving the success rates and false positive rates for the CIMS category in comparison to RF is difficult. This is because CIMS is a very narrow category of the broad “Caught in” group of accidents, and it shares lot of vocabulary with the group. Hence, for the experiments (iterations) in the ASECV model, the “Caught in” category was chosen. The aspiration is to build a successful model with strategies that can be applied to other models at later stage.

4.2. Results: ASECV Model

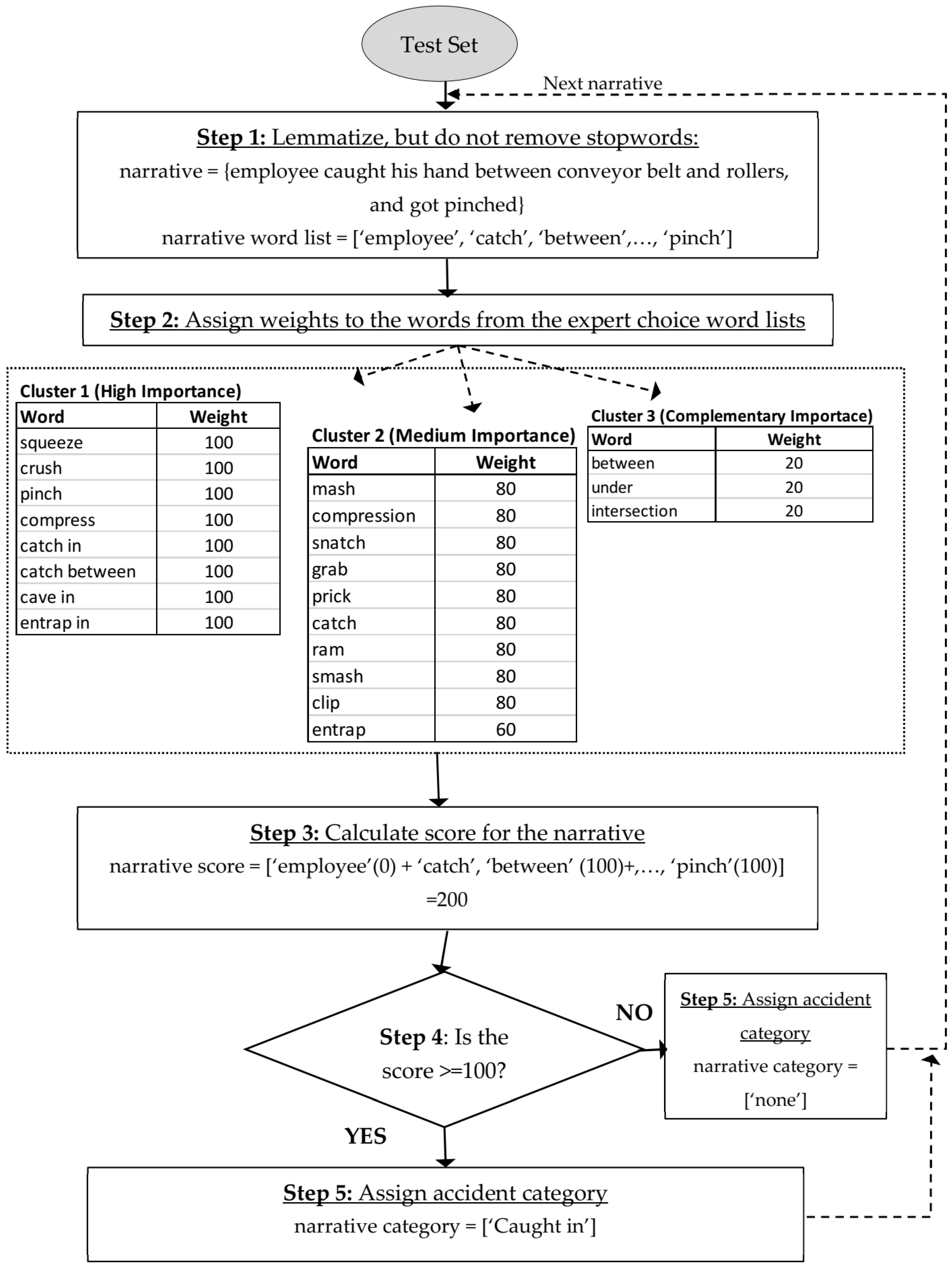

Table 7 shows the results for various ASECV vocabulary criteria in the “caught in” accident category. The clusters of vocabulary lists created from the training set are provided in

Table 7 as well. The clusters are classified according to the importance of the words they contain with respect to narrative classification. For instance, high, medium, and low or complementary type clusters have word weights of 100, 80, and 20, respectively, except for “entrap”, which has been given a weight score of 60.

Table 7.

RF vs. ASECV: “caught in” category performance for various criteria.

Table 7.

RF vs. ASECV: “caught in” category performance for various criteria.

| | | Vocabulary Sets by Importance | Target Category Predicted Accurately (n_target_accurate) | Success within Category: n_target_accurate/n_target | False Positive Rate: false_predicts/n_other |

|---|

High

Score: “100” | Medium

Score: “80”, Except ‘entrap’: “60” | Complementary/Low

Score: “20” |

|---|

| | Accident Category | Cluster 1 | Cluster 2 | Cluster 3 | RF | ASECV | RF | ASECV | RF | ASECV |

|---|

| 1 | Caught in | squeeze, crush, pinch, compress, catch in, cave in, entrap in | clip, ram, smash, mash | between, under, intersection | 3212 | 2941 | 71% | 65% | 1% | 1.76% |

| 2 | Caught in | squeeze, crush, pinch, compress, catch in, cave in, entrap in | clip, ram, smash, mash, entrap | between, under, intersection | 3212 | 2036 | 71% | 45% | 1% | 1.19% |

| 3 | Caught in | squeeze, crush, pinch, compress | clip, ram, smash, mash | | 3212 | 1629 | 71% | 36% | 1% | 0.85% |

| 4 | Caught in | squeeze, crush, pinch, compress, clip, ram, smash, mash, catch, entrap | | | 3212 | 1699 | 71% | 38% | 1% | 1.02% |

| 5 | Caught in | squeeze, crush, pinch, compress, clip, ram, smash, mash, catch, entrap, catch in, cave in, entrap in. | | | 3212 | 3480 | 71% | 77% | 1% | 6.21% |

| 6 | Caught in | squeeze, crush, pinch, compress | clip, ram, smash, mash | | 3212 | 1614 | 71% | 36% | 1% | 0.80% |

| 7 | Caught in | squeeze, crush, pinch, compress, clip, ram, smash, mash | | | 3212 | 2294 | 71% | 49% | 1% | 1.84% |

| 8 | Caught in | squeeze, crush, pinch, compress | | | 3212 | 1606 | 71% | 35% | 1% | 0.79% |

| 9 | Caught in | squeeze, crush, pinch | | | 3212 | 1602 | 71% | 35% | 1% | 0.76% |

| 10 | Caught in | squeeze, crush | | | 3212 | 166 | 71% | 0.04% | 1% | 0.31% |

| 11 | Caught in (ASECV * performance when stacked on RF) | squeeze, crush, pinch | | | 3212 | 103 | 71% | 8% | 1% | 0.42% |

The experiments or iterations (1–11) involve the adding and dropping of words to the clusters. This is to observe how different word combinations affect the success rates, as well as false positive rates, when applied to test set narratives. When new words are added to the clusters for an iteration, they were highlighted in the text (

Table 7). The process of adding or dropping words is first done systematically, by sorting the words according to their importance (using scores), and then by dropping one word at a time from the bottom of the list. Later, several combinations of words from each cluster are performed both systematically and heuristically based on the expert knowledge. The 11 iterations presented are the result of exploring many permutations and combinations. The success and false positive rates of the ASECV model are compared to the RF model side by side in the table.

For iteration 1, the full extent of the words list for each cluster was used. The success rate was 65%, with a false positive rate of 1.76%, which are low numbers when compared to the RF model rates of 71% and 1%, respectively. The overall focus is to reduce the ASECV model’s false positive rates to below 1%, which is comparable to RF performance in the same area (1%). This way, when ASECV is stacked over RF, there is minimal compromise in accuracy. In this context, the ASECV model outperforming the RF model is desirable. For iteration 2, the word “entrap” was added to cluster 2. The success rate dramatically reduced to 45%, while the false positive rate was slightly reduced to 1.19%. Removing the words (or prepositions) from cluster 3 (“between”, “under” and “intersection”) altogether in iteration 3 resulted in a lowering of the success rate to 36%. However, the false positive rate was brought down to 0.85%. It is interesting to see in iteration 4 that moving cluster 2 (clip, ram, smash, mash) and the word “entrap” to cluster 1 improved the success rate to 38%. The false positive rate, however, was only slightly increased (1.02%) from iteration 3. In iteration 5, certain phrases such as “catch in”, “cave in”, “entrap in” are added. The resulting success rates improved to 77%, which is better than the RF model, but the false positive rates stayed higher, at 6.21%, when compared to RF’s 1%. Iterations 6–9 demonstrated that the false positive rates can be reduced below 1% by gradually eliminating words to ultimately keep the words “squeeze”, “crush”, and “pinch” in cluster 1. The success rate at this point was 35%, but the false positive rate was reduced to 0.76%, which is highly desirable for the stacking approach. Dropping the word “pinch” in iteration 10 drastically reduced the success rate to 0.04%. This shows how important the word is to the model. In this context, the vocabulary set in iteration 9 is selected for stacking the RF model due to its low false positive rate.

Ultimately, in iteration 11, the narratives that the RF model failed to classify (assigned as “0”) into the “caught in” category (36,953 out of 40,649) were analyzed by the ASECV model. Hence, as a stacked model on the RF model, ASECV alone achieved an 8% success rate, with only 0.42% false positive rate, which is highly desirable (see highlighted text in iteration 11). The following are some dataset parameters used.

Total “test set” samples (n_samples) used = 40,649;

Total samples in target category (n_target) = 4524 (Caught in);

Total samples in other categories (n_other) = 37,339 (Caught in).

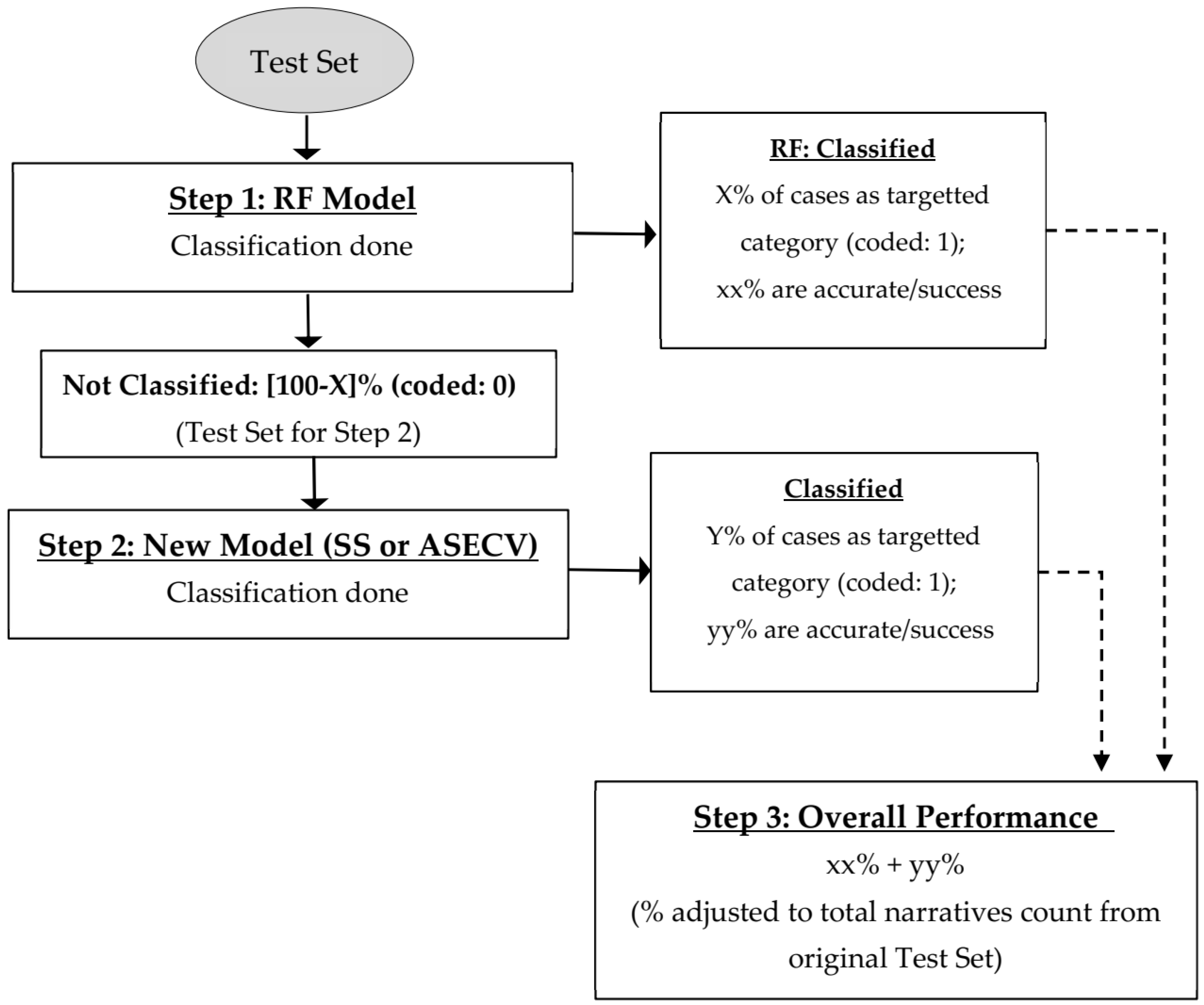

4.3. Results: Stacking Approach

Out of all the experimentations performed for the SS and ASECV models, iteration 11 of the ASECV model looked promising. Hence, it was used in stacking with the RF model from past research. The “stacking” approach has resulted in improving the overall success rate of the RF model from 71% to 73.28%, with only 1.41% false positive rate (

Table 8). Hence, it can be noticed that the “stacked model” has resulted in improving the existing success rates of the RF model.

Table 8.

Overall performance of the stacked model (RF when stacked with ASECV).

Table 8.

Overall performance of the stacked model (RF when stacked with ASECV).

| | Vocabulary Sets by Importance | Target Category Predicted Accurately (n_target_accurate) | Success within Category: n_target_accurate/n_target | False Positive Rate: false_predicts/n_other |

|---|

High

Score: “100” | Medium

Score: “80”, Except ‘entrap’: “60” | Complementary/Low

Score: “20” |

|---|

| Accident Category | Cluster 1 | Cluster 2 | Cluster 3 | RF | Stacked | RF | Stacked | RF | Stacked |

|---|

| Caught in | squeeze, crush, pinch | | | 3212 | 3315

(3212 RF + 103 ASECV) | 71% | 73.28%

(71% RF + 8% ASECV) | 1% | 1.41% |

5. Discussion

When RF model performance is compared with that of the SS model (

Table 6), certain interesting results can be observed. The success (5.1–99.8%) and false positive rates (1–96%) were poor in general and fluctuated in a wide range. In addition, high success rates were not always accompanied by low false positive rates. When narratives were classified into all nine (9) categories using all the vocabulary of each accident-related set (iterations 1 and 2 of

Table 5), the success rates were still poor (<10%). In iteration 3, when few categories were tried with exclusive words criteria, success rates improved (91%), while the false positive rates did not (stayed high at 24%). Through iterations 3–5, several combinations of exclusive (top 100) and frequent (top 25) words with a qualifying strategy that implements a limit on SS score “difference” between CIMS and notCIMS (rest of narratives) was tried. The 95-percentile limit on the difference should reduce the false positive rates. However, the false positive rates were still high (58%), despite the high success rates. The experiments prove that when it comes to narrow accident categories such as CIMS, the lack of exclusive vocabulary, specific to the category, seems to be a problem with the SS model—as it shares a lot of vocabulary with the broader “caught in” category and to some extent with other accident categories. Therefore, it is apparent that it becomes difficult to achieve high success rates while keeping the false positive rates below 5%.

When it comes to the ASECV model, from

Table 7, it can be observed that the false positive performance for the “caught in” category steadily improved up to iteration 9 (1.76 to 0.76%, which is on par with the RF rate of 1%). It can also be observed that when vocabulary lists (clusters) are reduced, they remained critical to classification until iteration 10. During the process of reducing the false positive rates (iterations 1–9), the success rates were also reduced (from 65% to 35%). Since it is important to keep false positive rates below 1%, compromise in success rates can be justifiable. Moreover, it can help improve the success rates of RF, if “stacking” of the ASECV model is performed. With stacking, the narratives that the RF model failed to categorize as “caught in” were sent to the ASECV model, anticipating that it can reclassify some of the narratives into the correct category. At iteration 11, when stacking was performed in such a fashion, the ASECV model improved its false positive rate performance (0.42%). Even though the success rate achieved was not a high number (8%), the very low false positive rates are highly desirable for stacking. For this reason, in the “stacked model” (

Table 7), the RF success rate was improved by 2.28% (from 71% to 73.28%). It can also be observed that at the 0.42% false positive rate, the ASECV vocabulary set only included three words, that are, “squeeze”, “crush”, and “pinch”. This demonstrates how important these words are to the model prediction accuracy on the test set. Even elimination of one word (“pinch”) can result in dramatic reduction in success rates to 0.04% (iteration 10). This again shows how important the above-noted three words are to the success rates in the classification process, as demonstrated in iterations 9 and 11. For this reason, the three-word set in cluster 1 is used in the stacking process (iteration 11). This shows how the field-specific expert knowledge can be leveraged in terms of using the proper set of words that can describe the key mechanisms of the accident occurrences. Accident-related vocabulary changes from industry to industry and often depends on the narrator’s style. If the vocabulary sets used can reflect these aspects, the classification success could be improved.

It can be understood that given the scope of this paper, to reduce the overall time expended and complexity in past modelling (RF and SS), the ASECV method is proposed. The ASECV algorithm operates on heuristics (linguistic rules) that are based on expert knowledge in mine safety. This approach dramatically reduced the size of the vocabulary sets used by past methods. In addition, as found by the authors, stacking the RF method with ASECV is an optimal method in terms of model performance compared to previous standalone RF approach.

6. Conclusions

NLP tools, if used strategically, can help process vast amounts of text into meaningful information. Accident narratives are concise descriptions of accidents that can help mines, as well as federal agencies, in analyzing accident data. Accident classification is the first and foremost of the steps involved in finding root causes for accidents. However, the process is manually intensive due to the sheer volume of text to deal with. In their previous application of NLP techniques and RF methods, the authors were able to successfully classify MSHA and non-MSHA (a surface metal mine) narratives. It was found that multiple RF classification models—one for each accident category—were effective in classification when compared to one model that can perform all classification tasks. The prediction success achieved was 75% and 96% (across the board) for MSHA and non-MSHA narratives, respectively. Minimizing the false positive rates to within 5% is of great importance for the accuracy of the model, and the RF models previously developed were able to achieve such rates. The insights provided (from previous work in Ganguli et al., 2021 [

6]) related to how often certain accidents occur at the partnering mine site (non-MSHA) helped the mine operator in taking preventive measures.

Furthering the research in the area, and in an attempt to improve upon the previous success rates (from RF), three approaches were presented in this paper. Two were novel approaches named, the similarity scores (SS) model and accident-specific expert choice vocabulary (ASECV) model, respectively. The third one is a “stacking approach”, where one of the successful novel methods is applied in combination with the RF approach. In the SS model, test narratives are scored based on the word weights they carry in accident-specific vocabulary lists developed during the training process. Word weights in the vocabulary lists are proportionate to their frequency of occurrence in narratives that belong to the related accident category. Narratives that scored highest among the vocabulary lists are assigned with the appropriate category. Since the model depends on the word frequencies, classification strategies were devised based on how rare or common a word is for an accident type. The model produced mixed success rates, but the false positive rates were very high, which is not desirable. This could be due to the fact most of the accident type narratives shared a certain amount of common (frequent) vocabulary. To compensate for this problem, the ASECV model was developed. The heuristically developed model’s predictions are based on vocabulary sets (clusters) that best describe the accident’s mechanism(s). Industry-specific expert knowledge was used in this context. By experimenting with the combination of key words—arranged in clusters of high, medium, and low importance—in predicting the targeted category, different success rates were achieved. With the ASECV model, the false positive rates were successfully reduced to below 1%, which is highly desirable. Even though the success rates of classification are moderate (39% across the board), such high accuracy rates helped the overall success of the ASECV model in “stacking” with RF model.

The ASECV classification model, when applied to the narratives (as a stacked option) —where the RF method failed to classify for “caught in” category—yielded an 8% success rate with less than 1% false positive rate. The combined stacked model (RF-ASECV) thus improved the previous RF model success rates from 71% to 73.28%. This, in turn, proves that when industry-specific knowledge is used in developing models along with powerful text-processing tools such as NLP, the accuracy of prediction can be improved. This paper demonstrates that use of domain-specific (mining industry) knowledge can improve accident classification success beyond what was achieved by RF, a popular machine learning technique. The models developed in the paper are focused on the “caught in” category due to limitations of scope. However, widening the application of the models to more accident categories, the exploration of semantic rules, and alternate performance measuring metrics will be considered for future research. Application of models developed to non-MSHA data is out of scope for the research presented in this paper; however, it can be considered for future research as well.