Crowdsourced Knowledge in Organizational Decision Making

Abstract

:1. Introduction

- Are there differences in the mental models of CTs and DMs? If so, how do they differ?

- Will crowdsourced knowledge provided by CTs significantly change perceptions of DMs? In what ways?

- What argumentation qualities, if any, affect how receptive DMs are to CT-provided organizational and/or tacit knowledge?

1.1. Crowdsourcing, Argumentation, and Design Thinking

1.2. Mental Models

1.3. Resistance to Change

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Procedure

2.2. Participants

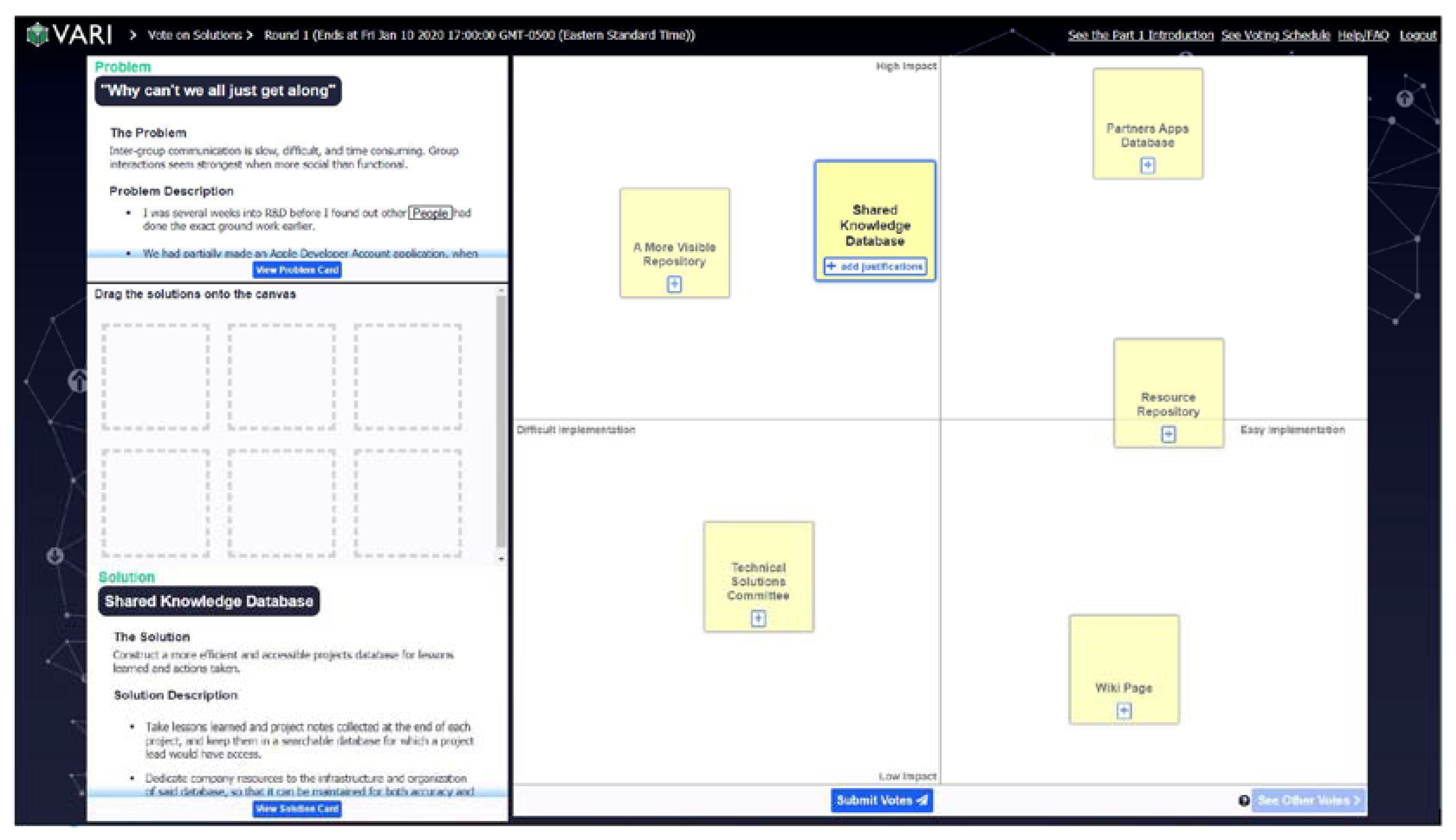

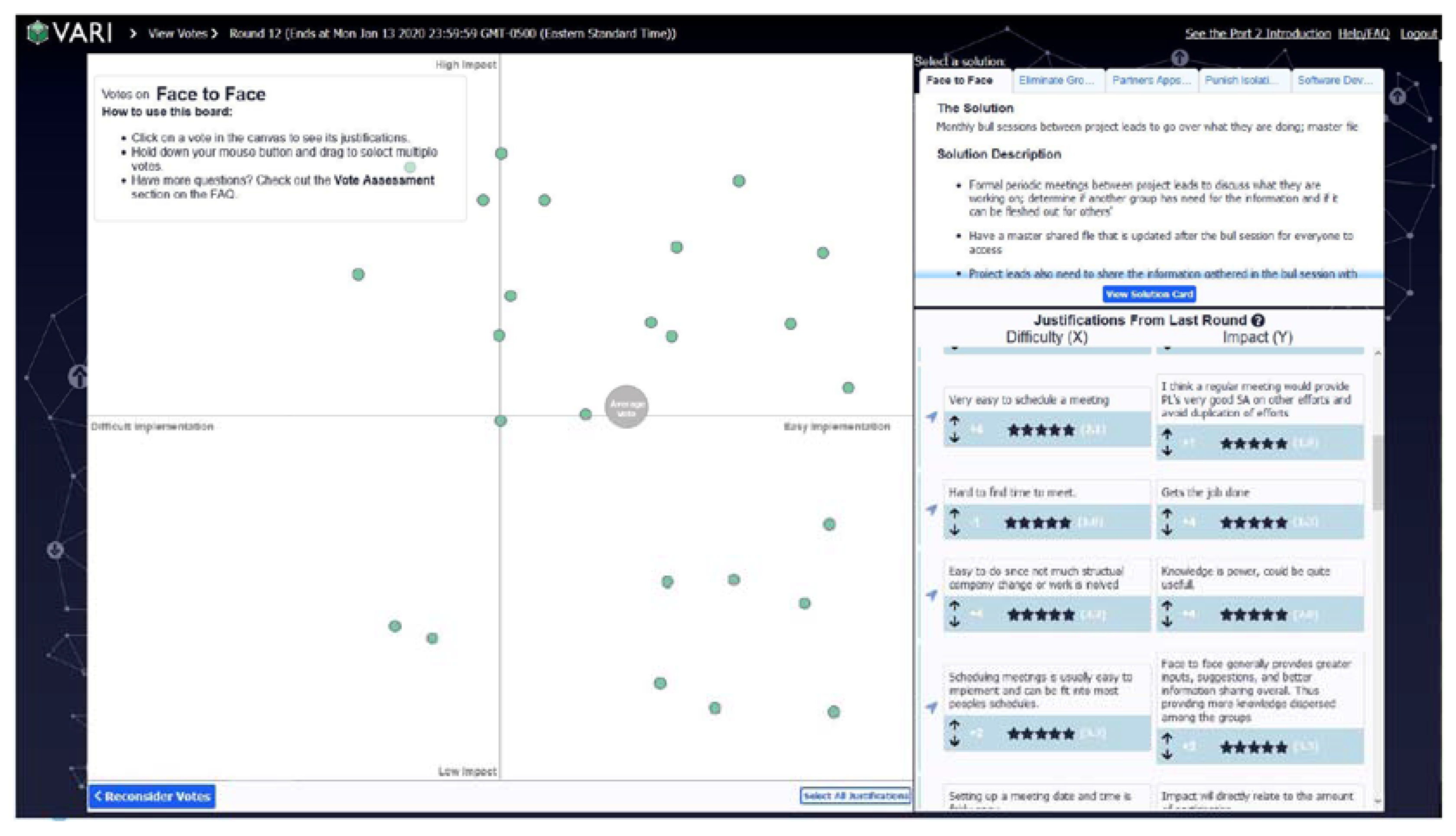

2.3. Apparatus

2.4. Dependent Measures

- Impact: The Y value of the solution on the voting canvas, normalized from −1.000 to 1.000, indicating the perceived impact of the proposed solution;

- Feasibility: The X value of the solution on the voting canvas, normalized from −1.000 to 1.000, indicating the perceived feasibility of the proposed solution;

- Distance to Ideal Solution (DI): The Euclidian distance of the solution’s median position (XMdn, YMdn) and the upper-right corner (1.000, 1.000), which represented the conceptual location of a solution that is perfectly impactful and perfectly feasible. As such, a lower DI indicates a more preferable solution.

3. Results

3.1. Did the DMs Vote Differently Than the CTs?

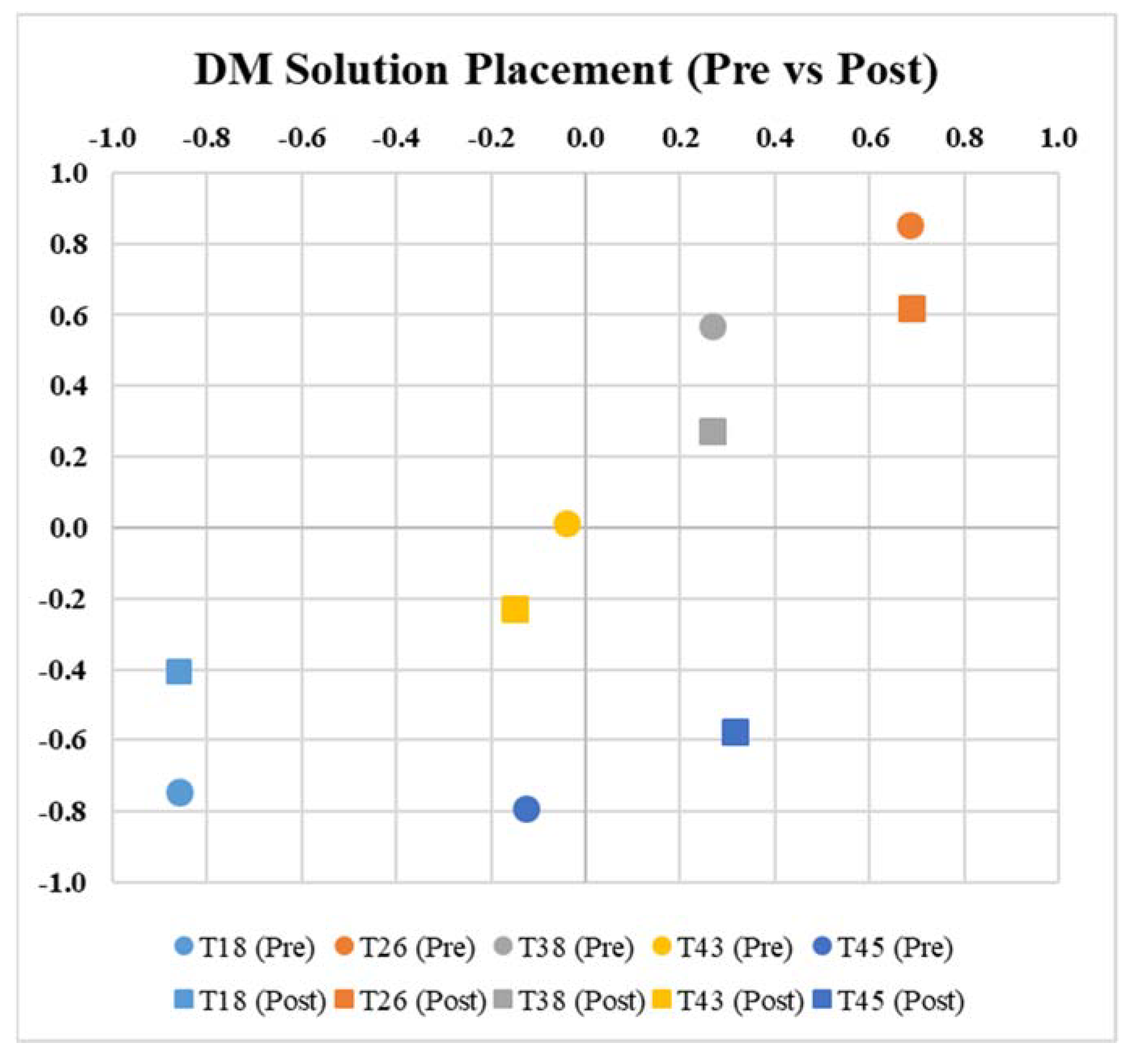

3.2. Did the CT Information Change the DM Votes?

3.3. What Argument Qualities Most Affected DM Voting?

4. Discussion

4.1. Key Findings and Discussion

- CTs and DMs had significantly different mental models regarding the relative impact and feasibility of candidate solutions to an organizational inefficiency. There were significant differences in how ideal each solution was perceived to be; however, there was no consistent pattern as to why. Given these differences, there was an opportunity for the CT-generated knowledge to have an actionable impact on the voting of DMs.

- Providing crowdsourced organizational knowledge from CTs had no significant impact on DM voting. That is, providing votes and argumentation from CTs caused only minor changes in DM voting, which were not significant in any dimension. These findings add weight to the case for phenomena such as decision inertia, confirmation bias, and anchoring, where DMs seemed to deviate only minimally from perspectives held prior to reviewing the crowdsourced knowledge.

- The aspect of CT arguments that had the greatest impact on DM voting was whether the solution conveyed an adequate sense of urgency that was commensurate with the inefficiency to be solved (RS = −0.54, p < 0.01). Despite this relationship, more DM voting was explained by whether they agreed or disagreed with the solution (RS = −0.83, p < 0.01). Thus, we found that DM voting was more strongly influenced by whether they inherently agreed with the solution, rather than any specific aspect of the argument (e.g., clarity or quality of evidence presented).

4.2. Possible Directions for Future Work

- Repeat this study with a different set of topics/solutions: It is possible that there was not significant movement in DM voting because, despite their relative impact and feasibility, DMs found all the proposed solutions to be inadequate (as evidenced by all DMs unanimously voting no on all five solutions). It is unclear if DMs would be more likely to change their position on topics that they felt were valid solutions to a problem at their organization.

- Incorporate DM feedback into content templates and repeat the study: The results showed that DMs favored solutions for which they found to have a requisite urgency to the problem at hand. Therefore, we may find that DMs are more likely to change their perceptions and voting if the solutions are posited in a manner that highlights their urgency. Similarly, previous studies showed that there are other considerations toward improving the argumentation templates [11,26].

- Allow DMs and CTs to co-develop solutions: As previously mentioned, a lynchpin of design thinking is the collaborative approach with all users and stakeholders [10]. The current VARI process explicitly makes both the identification and characterization of problems as well as the development and refinement of solutions a CT task. Future efforts should examine how CT and DM voting changes over time in an iterative process of co-creation, rather than having CTs develop solutions and then presenting them to DMs. There is a reasonable expectation that this would likely increase the DM ownership of that knowledge.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Howe, J. The rise of crowdsourcing. Wired 2006, 14, 1–4. Available online: https://wired.com/2006/06/crowds/ (accessed on 21 December 2021).

- Brabham, D.C. Crowdsourcing; The MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Quinn, A.J.; Bederson, B.B. Human computation: A survey and taxonomy of a growing field. In Proceedings of the SIGCHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, Vancouver, BC, Canada, 7–12 May 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Wiggins, A.; Crowston, K. From conservation to crowdsourcing: A typology of citizen science. In Proceedings of the 2011 44th Hawaii International Conference on System Sciences, Kauai, HI, USA, 4–7 January 2011; pp. 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Daniel, F.; Kucherbaev, P.; Capiello, C.; Benatallah, B.; Allabakhsh, M. Quality control in crowdsourcing: A survey of quality attributes, assessment techniques and assurance actions. ACM Comput. Surv. 2018, 51, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hackmann, J.R. Collaborative Intelligence: Using Teams to Solve Hard Problems; Barrett-Koehler Publishers: San Francisco, CA, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, J.; Sterman, S.; Cohen, A.A.B.; Bernstein, M. Mechanical novel: Crowdsourcing complex work through reflection and revision. In Proceedings of the 2017 ACM Conference on Computer Supported Cooperative Work and Social Computing, Portland, OR, USA, 25 February–1 March 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Chilton, L.; Little, G.; Edge, D.; Weld, D.S.; Landay, J.A. Cascade: Crowdsourcing taxonomy creation. In Proceedings of the SIGCHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, Paris, France, 27 April–2 May 2013; pp. 1999–2008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drapeau, R.; Chilton, L.B.; Bragg, J.; Weld, D.S. MicroTalk: Using argumentation to improve crowdsourcing accuracy. In Proceedings of the AAAI Conference on Human Computation and Crowdsourcing, Austin, TX, USA, 30 October–3 November 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Mercier, H.; Sperber, D. The Enigma of Reason; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Dorton, S.L.; Harper, S.B.; Creed, G.A.; Banta, H.G. Up for debate: Effects of formal structure on argumentation quality in a crowdsourcing platform. In International Conference on Human-Computer Interaction; Meiselwitz, G., Ed.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2021; pp. 36–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dorton, S.L.; Maryeski, L.R.; Ogren, L.; Dykens, I.T.; Main, A. A Wargame-Augmented Knowledge Elicitation Method for the Agile Development of Novel Systems. Systems 2020, 8, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dorton, S.L.; Ganey, H.C.N.; Mintman, E.; Mittu, R.; Smith, M.A.B.; Winters, J. Human-centered alphabet soup: Approaches to systems development from related disciplines. In Proceedings of the Human Factors and Ergonomics Society Annual Meeting, Liverpool, UK, 20–22 October 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Liedtka, J. Evaluating the Impact of Design Thinking in Action; Darden Working Paper Series; University of Virginia: Charlottesville, VA, USA, 2018; pp. 1–48. [Google Scholar]

- Dorton, S.L.; Maryeski, L.R.; Costello, R.P.; Abrecht, B.R. A Case for User-Centered Design in Satellite Command and Control. Aerospace 2021, 8, 303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, J.R. The place and value of mental models. In Proceedings of the Human Factors and Ergonomics Society 45th Annual Meeting, San Diego, CA, USA, 30 July–4 August 2000; pp. 49–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rouse, W.B.; Morris, N.M. On looking into the black box: Prospects and limits in the search for mental models. Psychol. Bull. 1986, 100, 349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nobre, F.S. Cognitive Machines in Organizations: Concepts and Implications; Verlag: Berlin, Germany, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Accenture. Overcoming the Barriers to Innovation: Emerging Role of the Chief Innovation Executive. 2008. Available online: http://www.innovationresource.com/wp-content/uploads/2012/07/Accenture-Study-of-Chief-Innovation-Officers.pdf (accessed on 22 December 2021).

- Carrington, D.J.; Combe, I.A.; Mumford, M.D. Cognitive shifts within leader and follower teams: Where consensus develops in mental models during an organizational crisis. Leadersh. Q. 2019, 30, 335–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, D.; Stabler, J.; Weinhardt, C. Investigating cognitive foundations of inertia in decision-making. KIT Sci. Work. Pap. Discuss. Pap. HeiKaMaxY 2018, 10, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alós-Ferrer, C.; Hügelschäfer, S.; Li, J. Inertia and Decision Making. Front. Psychol. 2016, 7, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Brown, A.; Karthaus, C.; Rehak, L.; Adams, B. The Role of Mental Models in Dynamic Decision-Making. 2009. Available online: https://apps.dtic.mil/dtic/tr/fulltext/u2/a515438.pdf (accessed on 21 December 2021).

- Besnard, D.; Greathead, D.; Baxter, G. When mental models go wrong: Co-occurences in dynamic, critical systems. Int. J. Hum. Comput. Stud. 2004, 60, 117–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Brewer, N.T.; Chapman, G.B. The fragile basic anchoring effect. J. Behav. Decis. Mak. 2002, 15, 65–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harper, S.B.; Dorton, S.L.; Creed, G.A. Design considerations for the development of crowdsourcing systems. In Proceedings of the Human Factors and Ergonomics Society Annual Meeting, Baltimore, MD, USA, 3–8 October 2021; pp. 432–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brooke, J. SUS: A “quick and dirty” usability scale. In Usability Evaluation in Industry; Jordan, P.W., Thomas, B., Werdmeester, B.A., McClelland, I.L., Eds.; Taylor & Francis: London, UK, 1996; pp. 189–194. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen, D.H. Evaluating arguments and making meta-arguments. Informal Log. 2001, 21, 73–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rife, M.C. Ethos, Pathos, Logos, Kairos: Using a Rhetorical Heuristic to Mediate Digital-Survey Recruitment Strategies. IEEE Trans. Dependable Secur. Comput. 2010, 53, 260–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hunt, K. Establishing a presence on the world wide web: A rhetorical approach. Tech. Comm. 1996, 43, 376–387. [Google Scholar]

- Higgins, C.; Walker, R. Ethos, logs, pathos: Strategies of persuasion in social/environmental reports. Acctng. Forum 2012, 36, 194–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wachsmuth, H.; Stede, M.; El Baff, R.; Al-Khatib, K.; Skeppstedt, M.; Stein, B. Argumentation synthesis following rhetorical strategies. In Proceedings of the 27th International Conference on Computational Linguistics, Santa Fe, NM, USA, 20–26 August 2018; Available online: https://www.aclweb.org/anthology/C18-1318 (accessed on 21 December 2021).

- Kotter, J. Leading Change; Harvard Business Review Press: Boston, MA, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Yoon, K.P.; Hwang, C. Multiple Attribute Decision Making: An Introduction; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Brooke, J. SUS: A retrospective. J. Usability Stud. 2013, 8, 29–40. [Google Scholar]

- Li, J.; Yuan, L.; Ning, L.; Li-Ying, J. Knowledge sharing and affective commitment: The mediating role of psychological ownership. J. Knowl. Manag. 2015, 19, 1146–1166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Spector, P.E. Behaviors in organizations as a function of employee’s locus of control. Psychol. Bull. 1982, 91, 482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, C. To share or not to share: Modeling knowledge sharing using exchange ideology as a moderator. Pers. Rev. 2007, 36, 457–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cummings, J.L.; Teng, B.-S. Transferring R&D knowledge: The key factors affecting knowledge transfer success. J. Eng. Technol. Manag. 2003, 20, 39–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Organizational Area | Roles |

|---|---|

| Executive Leadership | C-Suite 1 |

| Office of the Technical Director | |

| Board of Directors | |

| Infrastructure | Information Technology (IT) Department |

| Facilities Management | |

| Security | |

| Support Staff | Contracts |

| Accounting | |

| Human Resources and Benefits | |

| Business Development |

| Topic ID | Topic/Solution Title and Description |

|---|---|

| T18 | Eliminate Groups, Form Departments: The [Organization] should eliminate the group structure and form departments of expertise instead. |

| T26 | Face-to-Face: Monthly bull sessions between project leads to go over what they are doing. |

| T38 | Employee Apps Database: This is used in particular to stem the inefficiency of remaking the same applications. This is an app database with the name, description, and point of contact. |

| T43 | Software Development CZAR: Identify a single person to manage all external software development processes and procedures. |

| T45 | Punish Isolationists 1: Provide significant discretionary incentives to groups that do more cross-group proposals/work and penalties for those who do not. |

| Measure | Definition |

|---|---|

| Clarity | The degree to which the information provided is logically structured and understandable. |

| Quality of Evidence | The degree to which the evidence provided supports the asserted solution. |

| Credibility of Contributors | The quality of the intelligence, character, and goodwill of the people who contributed to this solution. |

| Relevance | How personally relevant this solution is to you (i.e., how much it affects you). |

| Urgency | As it is written, how well does the solution match the urgency of the inefficiency it aims to resolve? |

| Overall Quality | Regardless of whether you agree with the solution, what is the overall quality of the solution, as presented? |

| Overall Agreeability | Regardless of the quality of the solution, to what extent do you agree with the solution, as presented? |

| Vote | As it is written, this is a valid solution that merits implementation. |

| Soln. | Contributor (CT) * | Decision Maker (DM) ** | Difference | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ease (X) | Impact (Y) | DI | Ease (X) | Impact (Y) | DI | Ease (X) | Impact (Y) | DI | |

| T18 | −0.772 | 0.081 | 1.996 | −0.858 | −0.409 | 2.332 | −0.086 | −0.490 | 0.336 |

| T26 | 0.388 | −0.221 | 1.366 | 0.687 | 0.620 | 0.492 | 0.299 | 0.841 | −0.873 |

| T38 | 0.159 | −0.193 | 1.460 | 0.266 | 0.273 | 1.033 | 0.107 | 0.466 | −0.427 |

| T43 | −0.228 | −0.034 | 1.605 | −0.152 | −0.228 | 1.684 | 0.076 | −0.194 | 0.078 |

| T45 | −0.411 | 0.335 | 1.560 | 0.314 | −0.574 | 1.717 | 0.725 | −0.909 | 0.157 |

| Solution | Ease of Imp. (X) | Impact (Y) | Dist. to Ideal (DI) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| F | p | η | F | p | η | F | p | η | |

| T18 | 8.78 | <0.01 | 0.21 | 1.33 | >0.05 | 0.04 | 7.93 | <0.01 | 0.19 |

| T26 | 2.99 | >0.05 | 0.08 | 6.42 | <0.05 | 0.16 | 7.96 | <0.01 | 0.19 |

| T38 | 3.04 | >0.05 | 0.08 | 3.49 | >0.05 | 0.09 | 6.05 | <0.05 | 0.15 |

| T43 | 0.69 | >0.05 | 0.02 | 0.04 | >0.05 | 0.00 | 0.18 | >0.05 | 0.01 |

| T45 | 7.79 | <0.01 | 0.19 | 14.23 | <0.01 | 0.30 | 0.10 | >0.05 | 0.00 |

| Soln. | Pre-Assess | Post-Assess | Difference | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ease (X) | Impact (Y) | DI | Ease (X) | Impact (Y) | DI | Ease (X) | Impact (Y) | DI | |

| T18 | −0.858 | −0.744 | 2.548 | −0.858 | −0.409 | 2.332 | 0.000 | 0.335 | −0.216 |

| T26 | 0.854 | 0.683 | 0.349 | 0.687 | 0.620 | 0.492 | −0.167 | −0.063 | 0.143 |

| T38 | 0.569 | 0.268 | 0.849 | 0.266 | 0.273 | 1.033 | −0.303 | 0.005 | 0.184 |

| T43 | 0.011 | −0.041 | 1.436 | −0.152 | −0.228 | 1.684 | −0.163 | −0.187 | 0.248 |

| T45 | −0.125 | −0.791 | 2.115 | 0.314 | −0.574 | 1.717 | 0.439 | 0.217 | −0.398 |

| Solution | Ease of Imp. (X) | Impact (Y) | Dist. to Ideal (DI) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| F | p | η | F | p | η | F | p | η | |

| T18 | 0.68 | >0.05 | 0.03 | 0.83 | >0.05 | 0.04 | 0.23 | >0.05 | 0.01 |

| T26 | 0.21 | >0.05 | 0.01 | 0.08 | >0.05 | 0.00 | 0.03 | >0.05 | 0.00 |

| T38 | 0.17 | >0.05 | 0.01 | 0.12 | >0.05 | 0.01 | 0.05 | >0.05 | 0.00 |

| T43 | 0.61 | >0.05 | 0.03 | 0.22 | >0.05 | 0.01 | 0.43 | >0.05 | 0.02 |

| T45 | 0.13 | >0.05 | 0.01 | 0.06 | >0.81 | 0.00 | 0.25 | >0.05 | 0.01 |

| Quality Measure | Ease of Imp. (X) | Impact (Y) | Dist. To Ideal (DI) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Clarity | −0.05 | −0.15 | 0.17 |

| Quality Of Evidence | 0.18 | 0.17 | −0.19 |

| Asserter Credibility | −0.01 | 0.06 | −0.01 |

| Personal Relevance | −0.12 | −0.08 | 0.09 |

| Urgency | 0.35 * | 0.54 * | −0.54 * |

| Overall Quality | 0.08 | 0.08 | −0.08 |

| Overall Agreeability | 0.59 * | 0.79 * | −0.83 * |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Dorton, S.L.; Harper, S.B.; Maryeski, L.R.; Asiala, L.K.E. Crowdsourced Knowledge in Organizational Decision Making. Knowledge 2022, 2, 26-40. https://doi.org/10.3390/knowledge2010002

Dorton SL, Harper SB, Maryeski LR, Asiala LKE. Crowdsourced Knowledge in Organizational Decision Making. Knowledge. 2022; 2(1):26-40. https://doi.org/10.3390/knowledge2010002

Chicago/Turabian StyleDorton, Stephen L., Samantha B. Harper, LeeAnn R. Maryeski, and Lillian K. E. Asiala. 2022. "Crowdsourced Knowledge in Organizational Decision Making" Knowledge 2, no. 1: 26-40. https://doi.org/10.3390/knowledge2010002

APA StyleDorton, S. L., Harper, S. B., Maryeski, L. R., & Asiala, L. K. E. (2022). Crowdsourced Knowledge in Organizational Decision Making. Knowledge, 2(1), 26-40. https://doi.org/10.3390/knowledge2010002