Abstract

Good access and appropriate use of Water, Sanitation and Hygiene (WASH) is important in the control, elimination and eradication of a number of neglected tropical diseases (NTDs). Poor WASH access and use may explain continued high trachoma prevalence in Nabilatuk district, Uganda. This study aimed to investigate the level of WASH access and use through different WASH data collection methods and the triangulation of their results. A mixed-methods cross-sectional study was conducted in 30 households in Nabilatuk district, from 10 households in each of three nomadic villages. The data collection methods used were: (1) direct observations of routine WASH behaviours; (2) structured quantitative household questionnaires; (3) demonstrations of specific WASH behaviours. With regards to access, observations indicated less WASH access and use compared with questionnaire responses: the questionnaire indicated all households had access to an improved water source, but 70% had a >30-min round-trip, and no households had access to an improved latrine, whereas some observations indicated longer water collection times. In terms of behaviour, there were also differences between the data collection methods, with demonstrations revealing knowledge of good practice, such as thorough handwashing, but this was not routinely observed in the observations. Further systematic investigation of barriers to appropriate WASH access and use in the local context is needed, as is the development of feasible, valid and reliable WASH access and use assessment methods for use in national NTD programmes.

Keywords:

trachoma; water; sanitation; hygiene; Uganda; Chlamydia trachomatis; direct observation; questionnaire 1. Introduction

Alongside being a basic human right [1,2], Water, Sanitation and Hygiene (WASH) is an important factor in the control, elimination and eradication of a number of neglected tropical diseases (NTDs) [3,4] as good WASH access and use can reduce both disease exposure and transmission [5,6]. WASH access is commonly measured by WASH indicators recommended by the Joint Monitoring Programme (JMP): access to (1) safely managed drinking water services, (2) safely managed sanitation services, (3) handwashing facilities with soap and water [7]. Frequently used methods to collect these indicators include questionnaires and/or interviews such as Demographic Health Surveys (DHS) and Multiple Indicator Cluster Surveys (MICS), where data can be collected at household, school and healthcare facility levels [8,9,10]. These data are relatively simple to collect and build on objective measures, with some responses confirmed by direct observation of infrastructure [7]. However, some limitations to this method exist, such as access not necessarily equating to use, and indicators not confirmed by observation being subject to responder bias and thus possibly overestimating actual use. Alternative or complementary data collection methods could be used to provide more detailed and contextualised indications of WASH knowledge, access and use. Direct, unstructured observations of household residents’ routine behaviour can indicate routine WASH behaviours but is labour-intensive, time-consuming and might be subject to observer bias [11,12]. Demonstrations of certain procedures, such as of handwashing methods, is another potential method of assessing WASH knowledge and behaviour, but may again be subject to responder (social desirability) bias [13,14]. Thus, triangulating different data collection methods may be able to provide useful insights in WASH access and use through identification of consistent results between the approaches whilst elucidating possible gaps in both knowledge and behaviour. These data could then help inform NTD programme planning and decision-making [13,15,16,17,18].

Trachoma is an NTD, and the leading infectious cause of blindness worldwide [19]. It is caused by repeated ocular infection with the bacterium Chlamydia trachomatis. It is thought to spread directly through contact with ocular and nasal discharge, indirectly through contaminated surfaces and shared fomites (such as shared cloths and towels) and through the eye-seeking Musca sorbens fly, which preferentially breed in human faeces [20,21,22,23,24,25]. As a result, WASH is a critical component of the World Health Organization (WHO)-endorsed “SAFE” strategy for trachoma elimination as a public health problem by 2030 [3]: Surgery for trachomatous trichiasis (TT), Antibiotics to treat C. trachomatis infection, Facial cleanliness and Environmental improvement to limit transmission [26,27].

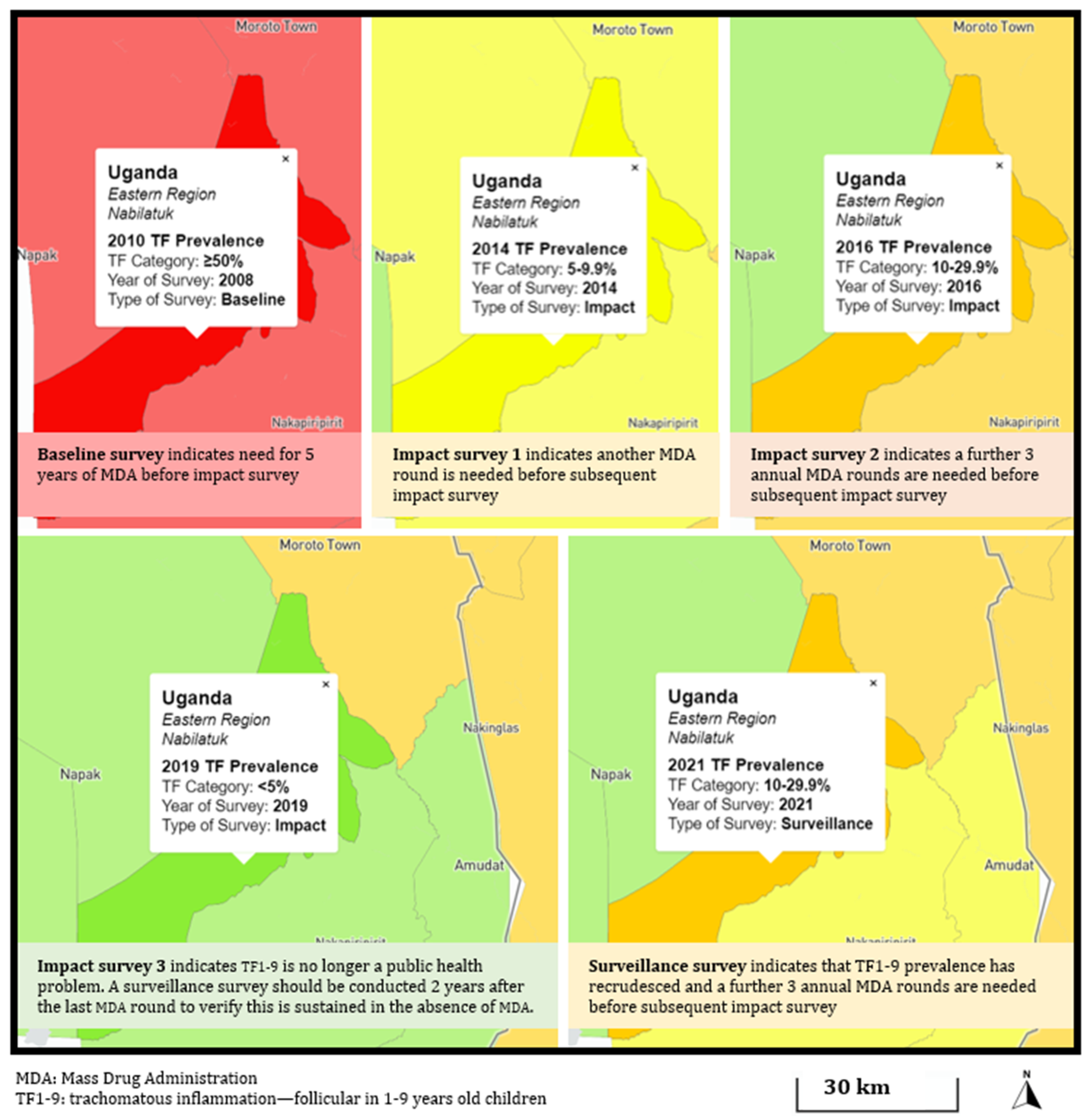

In Uganda, trachoma remains a public health problem despite years of SAFE implementation. Although great progress has been made at the country-level [28,29,30], the prevalence of trachomatous inflammation—follicular (TF) (the clinical sign associated with ocular C. trachomatis infection)—in 1–9-year-olds (TF1-9) is seen to remain above the 5% elimination threshold in certain areas [31,32,33]. In Nabilatuk district, TF1-9 has both been persistent (remaining above the 5% TF1-9 elimination threshold despite completing the WHO-recommended number of mass drug administration (MDA) rounds) and recrudescent (falling below the elimination threshold at impact survey, but exceeding the threshold at surveillance survey (Figure A1)) [34]. One hypothesis for the ongoing high trachoma prevalence in Nabilatuk district is poor WASH access and use. Structured household questionnaires as part of trachoma prevalence surveys are the main form of trachoma-related WASH data collection globally, consistent with the JMP methodology on WASH-indicators [8,35]. These data have previously reported poor access to water and sanitation facilities in Uganda [29].

This study therefore aimed to obtain detailed information on WASH knowledge, access and use in Nabilatuk district, using different WASH data collection methods. The specific objectives were to investigate WASH-related access and behaviour measured through different data collection methods, and to compare the results obtained from the different WASH data collection methods to help inform methodologies on WASH data collection as part of trachoma, and other NTD, programmes.

2. Materials and Methods

This study was a cross-sectional, mixed-methods study conducted in Nabilatuk district, Uganda.

2.1. Ethical Approval

The research protocol was approved by the Vector Control Division Research & Ethics Committee, Uganda, ref: VCDREC157, and the London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine Research Ethics Committee, UK, ref: 27035. Informed written consent was first obtained from the household head, followed by consent/assent from household members by signature or thumbprint. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants aged 18 years or older. Assent was obtained from all participants aged 1–17 years, together with written consent from their guardian. All households received a bar of soap in appreciation of their participation and to reinforce the face washing messages of the Ministry of Health.

2.2. Data Collection

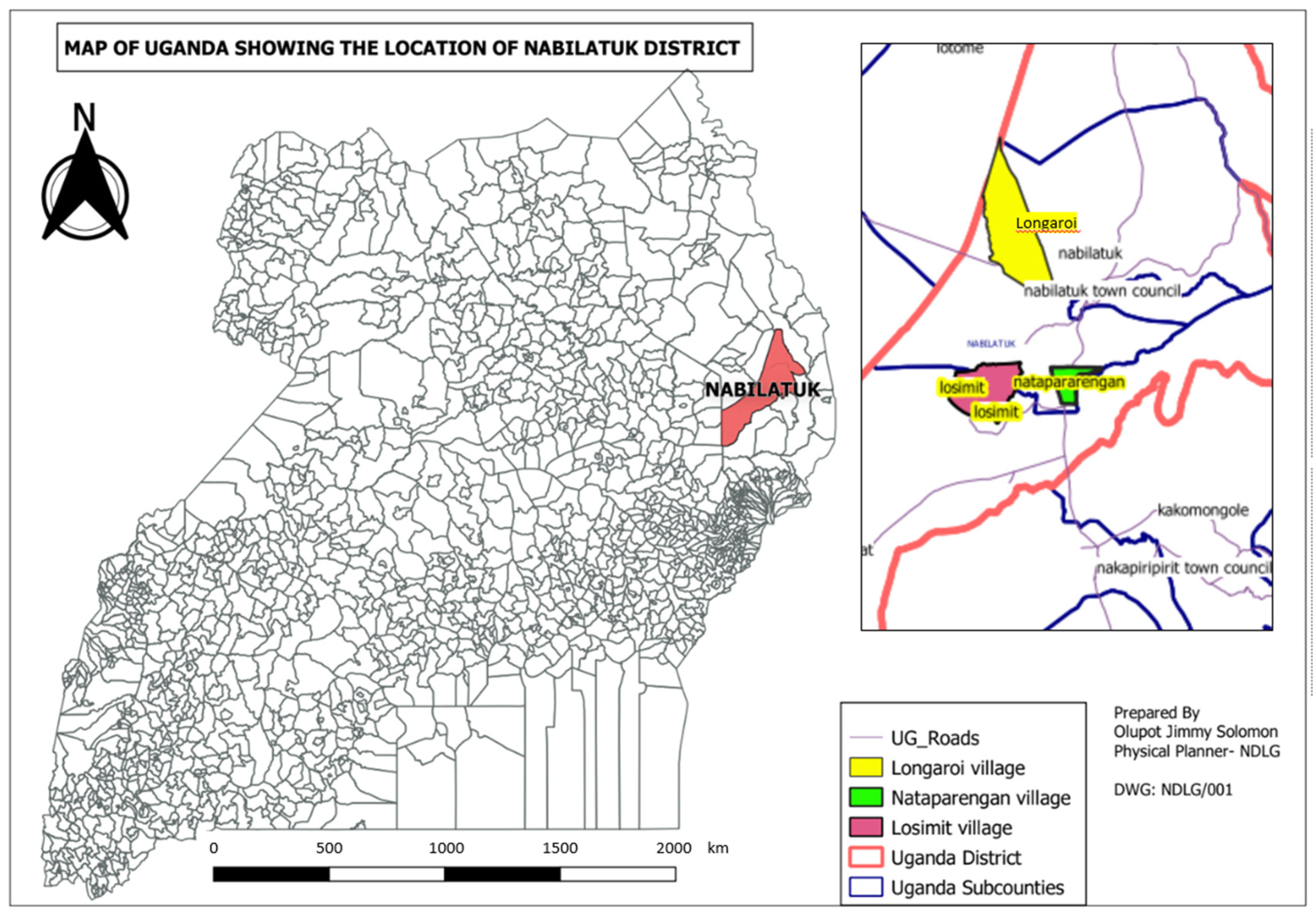

Data consisting of (1) unstructured behaviour observations [36,37], (2) structured questionnaires with spot checks [35] and (3) demonstrations of specific WASH-related behaviours [13] were collected by two field teams from 6 to 27 July 2022, from 30 households in three nomadic villages in Nabilatuk district: Losimit, Longaroi and Nataparengan, as shown in Figure 1. These villages were chosen as they were known to be nomadic populations settled in specific areas, making it possible to revisit the villages if required. The sample size of 10 households per village was decided based on the methods of a previous trachoma-related WASH qualitative study [17,38]. Four people collected the data, three of whom were local with some prior data collection experience, and the fourth was J.T.C.-J. from Denmark who had limited local field experience. Each field team consisted of two data collectors, rotating every day in order to limit bias in the observations and notes. J.T.C.-J. trained the data collectors in the different data collection methods for two days by going through why and how each data collection method was to be used and what the teams specifically had to pay attention to. Data from the first household were collected by all data collectors to ensure consistency in methods and limit possible errors. The collected data were reviewed by the four data collectors at the end of each day, both to find and discuss any discrepancies and to align data to be as uniform as possible throughout the study.

Figure 1.

Location map showing position of Nabilatuk district in Uganda, and the three villages Losimit, Longaroi and Nataparengan in Nabilatuk district.

2.2.1. Household Recruitment

Two households were observed per day (one by each team), with 10 households included from each village. For the purposes of this study, a household was defined as a mother and her children living within the same compound. Households were eligible if residents were at home and contained at least one child aged 1–9 years. The ten households from each village were selected systematically by calculating the sampling interval by dividing the total number of households by 10, with the total number of households in each village obtained by asking the village leader. The first household in each village was randomly selected and the sampling interval added to that in order to select the remaining nine households. If the selected household did not meet the inclusion criteria, the nearest household was approached for invitation to participate instead.

2.2.2. Unstructured Behaviour Observations

Following the methods previously described [17], the unstructured behaviour observations of each household member were collected for each household to better understand household daily routines. In order to limit bias, these data were the first to be collected, and the study was described to households as investigating ‘daily routines’ rather than specifically WASH- or trachoma-related behaviours. Furthermore, interaction with household members was minimised so as not to affect routine behaviours. Observations took place for three hours each day, with the field teams aiming to start observations between 9 and 10 am. Behaviours of interest included WASH procedures (such as washing hands before eating or after going to the toilet, face washing, and bathing), sleeping patterns and sharing of hygiene fomites. For each observation, time, place and household member were recorded (Appendix B).

2.2.3. Structured Questionnaire with Spot Checks

The structured questionnaire was collected for each household after completion of the unstructured observations. The oldest woman in the household answered the questions, following evidence that this provides the most reliable responses to WASH-related questions [39]. As per routine practice during trachoma prevalence surveys, the direct observation of some responses, such as presence and type of latrine, was conducted to confirm responses. Additional questions were added, such as recalling receiving MDA in the last round and the number of children aged 1–9 years living in the household, as well as more detail regarding practices such as face washing, sleeping patterns and washing of bed sheets [7,8,17]. The full questionnaire is provided in Appendix C. This questionnaire served to provide quantitative data on WASH access and use, consistent with the questionnaire used in routine trachoma prevalence surveys [35].

2.2.4. Demonstrations of Specific WASH-Related Behaviours

Following the structured questionnaire, the questionnaire respondent (oldest woman) was then asked to demonstrate how she performed face and hand washing by asking: “Can you please demonstrate how you usually wash your hands and face?” This served as a direct method of evaluating knowledge regarding the specific procedures [40]. All actions from asking the question were recorded as follows: where the water was collected from; how the water was poured; how many times hands and face were rinsed with water; if water was reused; what equipment was used such as cups, soap or basin; if used equipment was readily available or collected from somewhere (and if so, how long it took to collect).

2.3. Data Storage and Management

Data were recorded on paper forms, which were stored in a locked room during data collection and later at the Ministry of Health in Uganda. The structured questionnaire was then entered into Excel (Microsoft Office Professional Plus 2019, version 2211, Redmond Washington, DC, USA) twice by J.T.C.-J., and then the two entries were compared. If there were discrepancies, the original was checked for the correct answer. The observation and demonstration notes were typed into NVivo v12 (QSR International, 2018, https://www.qsrinternational.com/nvivo-qualitative-data-analysis-software/home accessed on 4 January 2023) and read through to ensure consistency with the original notes. No electronic data contained identifiable information. The quantitative data were cleaned and exported to R (v 4.1.2, R Core Team, 2022, Vienna, Austria [41]) for analysis.

2.4. Data Analysis

2.4.1. Unstructured Behaviour Observations

A thematic analysis was conducted to analyse the unstructured observations [42]. The observations were further analysed to determine the following: how washing procedures were carried out; when washing procedures were carried out; whether water and soap were being used; where participants defecated; when handwashing took place.

2.4.2. Structured Questionnaire with Spot Checks

Data were categorised as per the JMP sanitation ladder, using the following measures [43]: reported access to an improved water source; reported access to an improved drinking water source within a 30-min journey; observed access to an improved latrine; observed access to a handwash station.

2.4.3. Demonstrations of Specific WASH-Related Behaviours

The demonstrations were analysed to determine the following: where water was collected from; what equipment was used (soap, sand, cup, basin, towel, etc.); how long it took to find the equipment; the number of times hands and face were rinsed with water; the amount of water used; whether water was reused or poured to the ground.

2.4.4. Comparison of Data Collection Methods

The demonstration data were compared with the unstructured observation data to look for differences in procedures that were observed in both. The unstructured observation data were used to validate the responses to the structured quantitative questionnaire.

3. Results

3.1. WASH-Related Behaviours

Out of a total of 631 households (214 in Longaroi, 194 in Losimit and 223 in Nataparengan), 30 households took part in the unstructured observations, structured questionnaire and demonstrations. An area consisting of around 100 households in Longaroi could not be included due to safety issues. Thus, the sampling of the 10 households in Longaroi was out of the 114 where access was safe.

3.1.1. Unstructured Behaviour Observations

An average of seven people lived in a household, ranging from 3 to 10 people, of whom 1–6 were children aged 1–9 years. Table 1 summarises the behaviours recorded during the unstructured observations.

Table 1.

Summary of behaviours during the unstructured observations.

In terms of environment, animals lived close to households, and both animal and human faeces were frequently observed both within the compound and in the surrounding areas. Many compounds were dirty, and days of accumulated faeces and grass were present. Household members often started sweeping not long after the start of the observations, and water collection ranged from 10–120 min. In terms of water use and hygiene, both bathing and hand washing were generally performed without soap. Face-washing was rarely observed independent of bathing. Use of soap during dishwashing varied among family members. With regards to sanitation, most households practised open defecation, as evidenced by the lack of functional latrines and the presence of faeces within and surrounding the compounds. Combined with the smell of urine, it was apparent that urination was frequently performed within the compound. The most observed removal of children’s faeces was calling the dog to eat it. Some households buried the faeces; however, this would often be observed to be superficial. Handwashing was observed 23 times; however, none were after sanitary practices but instead were after activities such as gardening. Handwashing was not observed after any sanitary (defecation-related) procedure. Food preparation was carried out sitting on the ground, both inside or outside the house. Handwashing was not common prior to eating or preparing food, and eating was generally performed without cutlery.

3.1.2. Structured Questionnaire with Spot Checks

Table 2 presents a summary of selected results from the structured questionnaire; a full summary of the questionnaire results can be found in Table A1.

Table 2.

Selected structured questionnaire results.

All 30 households reported access to an improved water source; however, the median time to collect water was 60 min, ranging from 10–270 min. When grouped into above or below 30 min, 70% (21/30) of households reported a >30-min return journey. Two households reported access to a latrine, which was confirmed by observation. However, neither of these had a slab and could therefore not be classified as improved. All households reported using mobile objects as handwashing facilities, confirmed by observation, although only one was visible and filled with water at the time of visit. Burying was the most common method of disposing of children’s faeces, followed by leaving it in the open or calling the dog to eat it. More than 90% of the female heads of household reported washing their face the same morning and washing their face every day. The reported frequency of handwashing after defecation and handling of children’s faeces was high, while handwashing after urination was less common. Although face washing was common (97%), respondents sometimes qualified their answers by saying it only took place if soap or sufficient water were present.

3.1.3. Demonstrations of Specific WASH-Related Behaviours

The majority of participants used the quantity of water equal to the cup size that they had available to them for face washing and hand washing. Furthermore, the most frequent observed procedure was to rinse their hands and face with water, without soap, three times each. The participants who used soap spent time collecting it from the house, indicating that this was not habitual behaviour. Twice, outsiders interfered with how the participant did the demonstration. The demonstration observations are summarised in Table 3.

Table 3.

Summary measures of the observations made during the demonstrations of face and handwashing.

3.2. Comparison of Data Collection Methods

Comparison of the unstructured observations and the structured questionnaire involved three variables: time to collect water, handling of children’s faeces and handwashing after handling children’s faeces (Table 4). The three variables had 35 data points that were in common between the questionnaire and the observations. Of the 35, 19 (54%) of the observations confirmed answers reported in the questionnaire. In contrast, 16 (46%) observations contradicted the questionnaire answers: seven for water collection (five were observed to take longer than reported in the questionnaire, and two shorter); five for handling children’s faeces (four reported burying but were observed leaving the faeces in the open, and one answered leaving it in the open but was observed superficially burying faeces); four regarding handwashing after handling of children’s faeces (all were observed not washing their hands despite reporting that they did).

Table 4.

Observation and questionnaire response comparisons.

During the demonstrations, three main differences in improved practice were revealed when compared with the unstructured observations. First, handwashing was more thorough, and the use of soap was improved. Second, more households washed their hands directly in the water in a basin during the observations than during the demonstrations. Third, some participants did not use soap in the demonstration, even though it was observed as being available earlier in the observations.

4. Discussion

The combination and cross-validation of data from different collection methods demonstrated both poor WASH access and use in Nabilatuk district, Uganda. Despite a high proportion of households having access to improved water sources, time to collect water was long and access to soap was limited, which may explain the observed poor water-use behaviour. Because only two households had a latrine, it is unsurprising that open defecation was common. Further, WASH behaviour demonstrations uncovered gaps in knowledge of good hygiene behaviour practice, indicating the need for improved hygiene promotion interventions. The combined data indicated that limited hygiene and sanitation access underpinned poor WASH-related behaviours, as some knowledge of correct behaviours was evident but routine practice of these behaviours was not.

Facial cleanliness and environmental improvement are key components for the SAFE strategy for trachoma elimination [26]. Despite multiple MDA rounds, TF prevalence is not being sustained below the elimination threshold in Nabilatuk district [44]. Structured questionnaire data collected during routine trachoma prevalence surveys in 2021 in this district by the Ministry of Health demonstrated that access to an improved water source was already high (89.5%), but the proportion of households with access to an improved water source within a 30-min journey was low (33.9%). Our findings, albeit on a smaller sample size, support these findings. However, the benefit of having used a mixed-methods approach is the ability to explore WASH-related behaviour beyond a structured questionnaire, and outside of a disease-specific programmatic activity, such as a trachoma prevalence survey, thus providing more in-depth insight into WASH access and use. Furthermore, this approach enabled us to compare the findings from the different data collection methods, facilitating cross-validation and providing higher reliability than the routine trachoma prevalence survey structured questionnaire alone.

The different data collection methods each had their relative strengths and weaknesses. The unstructured observations proved less biased than the questionnaire and demonstrations. However, unstructured observations are time-consuming and may still be prone to desirability bias through the presence of an external researcher in the household [12]. Demonstrations provide useful insight in terms of knowledge of correct procedure, but again suffer from desirability bias in terms of practices performed [14]. However, observation and demonstration data combined can help indicate knowledge gaps regarding correct procedure versus poor routine practice. Triangulation with the quantitative data, which provide information on access to necessary infrastructure (albeit prone to recall and responder bias), provides the most informative means of understanding WASH access and use. For routine data collection, it might improve insights to also collect demonstration data (which only take 5–10 min per household) and compare these to the questionnaire data, as these complementary data will indicate if knowledge regarding procedures can be improved.

There were several limitations to this study. First, bias in the household sampling may have been introduced due to inaccessibility of an area of around 100 households in Langaroi. Second, it is possible that not all the important WASH-related behaviours were observed, not only because of the short observation time, but also because procedures such as cooking and washing took place both inside and outside the household. The houses were small, and the field teams would not always go inside so as not to intrude or make children uncomfortable by being in close contact with strangers. Third, the start time of the observations varied for some households (observations started between 11 a.m. and 2 p.m. for three households rather than the planned 9–10 a.m. start), which could have affected the quality and quantity of data collected. Fourth, the field teams’ presence and the fact that they introduced themselves as representatives of the Ministry of Health could have introduced bias, overestimating the observed standard of WASH-behaviours. Fifth, as the questionnaire was conducted the same day as the observations for each household, it is possible that information about the questions asked could have been communicated to the rest of the village before the work ended, thus influencing the responses and observations from the later-recruited households. Lastly, data collected in the unstructured observations on face- and handwashing procedures tended to be less detailed than those during the demonstrations, which limited a detailed comparison of these two data collection methods.

Our study highlights the importance of collecting data on WASH-related behaviour, and not only of structures. The unstructured observational methods used in our study adapted those previously used for understanding hygiene behaviours in a trachoma elimination context in Ethiopia [17]. Due to the nature of qualitative data, results are not easily generalisable, but they can still provide valuable insights into a local context [45]. To gain further insight into WASH-related behaviours, we would need to increase the amount of time for which observations are conducted, conduct data collection at different times of year (for example in both the dry and rainy seasons), and validate results with additional data collection methods such as focus group discussions. These activities are time and resource intensive and would not be feasible as part of routine programmatic activity. Even the less intensive unstructured observations we conducted are unlikely to be routinely implementable in a community setting. One option may be to encourage WASH-related behaviour change in schools, where monitoring would be easier to conduct [18]. However, this is dependent on high school attendance rates, which is uncertain in areas such as Nabilatuk district [46,47]. Objective, valid and implementable measures to monitor and evaluate facial cleanliness and environmental improvement interventions for trachoma elimination purposes remain a challenge and potentially threaten the achievement and sustainability of reaching the trachoma elimination goals [4,48].

Further, despite previous evidence of associations between WASH measures and trachoma prevalence from observational studies, the evidence-base from randomised trials to support WASH interventions to reduce trachoma prevalence is weak [49,50,51,52]. This suggests that even if access to latrines and time to collect water is improved, other measures are required to successfully eliminate trachoma. Following the WHO informal consultation on end-game challenges for trachoma elimination in 2021, tailored management activities relating to the “A”, “F” and “E” components of the SAFE-strategy were proposed and recommended to help districts with persistent or recrudescent TF1-9, such as Nabilatuk, to meet and maintain the elimination thresholds [34]. Uganda is now adopting the more-frequent-than-annual MDA distributions option for persistent districts for the next two years, and the additional annual rounds strategy for recrudescent districts (one more year).

The lack of WASH access is likely a marker of the wider social and economic challenges faced by the people of Nabilatuk. The Integrated Food Security Phase Classification classifies Nabilatuk district at a serious level of malnutrition (level 3 out of 5, where 5 is highest) [53], which supports anecdotal observations of malnourished children by the study team. Malnutrition, morbidity/mortality from infectious agents, and poverty are closely linked and part of a vicious cycle [54,55]. As such, individuals who are blind due to trachoma are unable to contribute economically, and ocular C. trachomatis infection transmission is facilitated by crowded living conditions and poor WASH access and use, which are associated with poverty [19,56]. Achieving the Sustainability Development Goal of no poverty [57] is beyond the remit and capabilities of an NTD programme, but successful implementation of the SAFE strategy could help interrupt the poverty cycle.

Challenges to successfully implementing environmental improvement interventions were observed in the study villages, highlighting the need for local, context-specific strategies. Several non-functional pipes were observed close to the homes, and multiple unfinished latrines were observed around the villages. Households reported that the reason for non-completion was the requirement for local community efforts to finish the work. A 2015 study in Uganda found that policy changes made the maintenance of water supply and infrastructure more complex as collaboration between many partners, including the local communities, was needed [58]. Household members may also not see a need to finish constructing the latrines because of their nomadic lifestyle [59]. These unfinished efforts indicate the government must work closely with the communities to identify culturally appropriate solutions to improve WASH access and use. Future qualitative research examining barriers and facilitators to successful intervention implementation could reveal important insights to guide programmatic policy.

5. Conclusions

Through a mixed-methods approach, we were able to demonstrate poor WASH behaviours, due to lack of access to WASH infrastructure and lack of knowledge of recommended practice. Future studies should include data collection in different seasons, longer observation times and larger sample sizes. To strengthen efforts to improve overall WASH access and use in Nabilatuk district, solutions that are tailored to this nomadic population’s access to and use of WASH are required. There is also a need for feasible, valid and reliable WASH access and use assessment methods for use in national programmes. Collecting demonstration data alongside household WASH questionnaires could be one option for helping assess WASH-related knowledge and behaviour during routine programme activities and indicate the need for health promotion interventions.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.T.C.-J., G.B. and E.H.-E.; methodology, J.T.C.-J., G.B. and E.H.-E.; formal analysis, J.T.C.-J.; investigation, J.T.C.-J. and G.B.; resources, G.B.; data curation, J.T.C.-J.; writing—original draft preparation, J.T.C.-J.; writing—review and editing, J.T.C.-J., E.M., G.B. and E.H.-E.; supervision, E.M., G.B. and E.H.-E.; project administration, E.M., G.B. and E.H.-E.; funding acquisition, J.T.C.-J. and E.H.-E. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

Josefine Tvede Colding-Jørgensen has received funding from: London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine, UK, Trust Fund and Bench Fees; Reinholdt W. Jorck og Hustrus Fond, jr.nr. 20-JU-0346; Ib Henriksens Fond jr.nr. 2020-0409; Knud Højgaards Fond, jr.nr. 21-01-2827; Aage og Johanne Louis-Hansens Fond, jr.nr. 21-2A-9091; Gerhard Brønsteds Rejselegat, jr.nr. 17-300085; Fabrikant Aage Lichtingers Legat, jr.nr. 91073001; William Demant Fonden, jr.nr. 21-1812; Beckett-fonden, jr.nr. 22-2-9111.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Ethics Committee of Vector Control Division Research & Ethics Committee, Uganda, ref: VCDREC157, 13 June 2022, and the London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine Research Ethics Committee, UK, Ref: 27035 4 July 2022.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all adults and informed assent, plus consent from guardians, were obtained from all participants under the age of 18 involved in the study. As the majority of participants were illiterate, thumbprints were obtained as a signature.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to participant confidentiality and anonymity, as outlined in the ethics applications and informed consent procedures.

Acknowledgments

We thank Lubega Sharif, Okala Denis, Chelina Lokubal, Ongom Charlse and Korobe Mwanaidi for their support throughout the fieldwork.

Conflicts of Interest

E.H.-E. receives salary support from the International Trachoma Initiative at The Task Force for Global Health, which receives an operating budget and research funds from Pfizer Inc., the manufacturers of Zithromax® (azithromycin).

Appendix A

Figure A1.

Maps showing how trachoma prevalence has changed over time in Nabilatuk district, Uganda. https://atlas.trachomadata.org/ accessed on 4 January 2023.

Figure A1.

Maps showing how trachoma prevalence has changed over time in Nabilatuk district, Uganda. https://atlas.trachomadata.org/ accessed on 4 January 2023.

Appendix B. Data Collection form for Unstructured Observations

| Household number_______________ | Date____________________ | Observer ID_______________ | ||

| Time | Place | Household Member | Observation | Description |

Appendix C. Data Collection form for Structured Questionnaire

| Question | Answer |

| Date | |

| Observer ID | |

| Household number [ekimar angikenoi] | |

| Has informed consent been obtained [echamuna ngakiro nguna] | |

| How many household members? [Ngia ekimar angitunga alokenoi] | |

| Did you receive MDA for trachoma in the last round? [Ibuiyong toryam ngikito lu a lokir ngulu lachakineta?] | Yes |

| No | |

| How many children aged 1–9 years in the household? [ngide ngiai eya ngikar epei tar akitodol ngikankomon alo to ma ekeeno] | |

| Do you have one or more child under 3 years of age in the household? | |

| In the dry season, what is the main source of drinking-water for members of your household? [Alotoma akamu ay eriamuniata ngituanga alokenokon ngakipi?] | Piped water into dwelling |

| Piped water to compound/yard /plot | |

| Piped water to neighbour | |

| Public tap/standpipe | |

| Tubewell/borehole | |

| Protected dug well | |

| Unprotected dug well | |

| Protected spring | |

| Unprotected spring | |

| Rainwater collection | |

| Delivered water | |

| Water kiosk | |

| Packaged water (bottled water, sachet water) | |

| Surface water (e.g., river, dam, lake, pond, stream, canal) | |

| Other: ____________________ | |

| How long does it take to go there, get water, and comeback? [Eari ngthia ngiyay toriam nakipi akilot ka abongun?] | Water source is in the yard (do not collect) |

| Type minutes __________ | |

| Don’t know | |

| In the dry season, what is the main source of water used by your household for washing faces? [Alotoma akamu ngakipi ngunerai nukai ethitianete ngitunga alokenkon akilothia ngakonyen?] | Piped water to compound/yard /plot |

| Piped water to neighbour | |

| Public tap/standpipe | |

| Tubewell/borehole | |

| Protected dug well | |

| Unprotected dug well | |

| Protected spring | |

| Unprotected spring | |

| Rainwater collection | |

| Delivered water | |

| Water kiosk | |

| Packaged water (bottled water, sachet water) | |

| Surface water (e.g., river, dam, lake, pond, stream, canal) | |

| Other: ____________________ | |

| How long does it take to go there, get water, and comeback? [Eari ngthia ngiyay akidol neni to riam ngkipi kabongunit?] | Water source is in the yard (do not collect) |

| Type minutes __________ | |

| Don’t know | |

| In the last month, has there been any time when your household did not have sufficient quantities of drinking water when needed? [Alotoma elap ngolo bien adaun ayayi edi tha ngolo acamitor ekon keno ngakipi ngunamatan kitanttetai?] | Yes |

| No | |

| Don’t know | |

| Is the water supplied from your main source [W1] usually acceptable? [Ngakipi nguna ekorio alomateta kuth ecamunterea?] | Yes, always acceptable |

| No, unacceptable taste | |

| No, unacceptable colour | |

| No, unacceptable smell | |

| No, contains material | |

| No, other __________ | |

| What do you usually do to the water to make it safer to drink? [Nyomonokona itianakini iyong nakipi toruorotor nguna ajuak akimat?] | Boil |

| Add bleach/chlorine | |

| Strain it through a cloth | |

| Sse water filter | |

| Solar disinfection | |

| Let it stand and settle | |

| Other __________ | |

| Don’t know | |

| The last time the youngest child passed faeces, what was done to dispose of faeces? [Kiyakatar iyong ikoku ipei kori ngiarei ngikaru ngiuni kwap alokenokon, apak ngina ebobontor ikoku, nyo aponi kityakinai alemaria ngakeciin?] | Child used toilet/latrine |

| Put/rinsed into toilet/latrine | |

| Put/rinsed into drain or ditch | |

| Thrown into garbage (solid waste) | |

| Buried | |

| Left in the open | |

| Other _____________ | |

| Don’t know | |

| Where do you and the other adults in the household usually defecate? [Ani yong kangulucie apolok alokeno kon ay elothenoo ieth moding?] | Shared or public latrine |

| Private latrine | |

| No structure, outside somewhere | |

| Other _____________ | |

| What kind of toilet facility do the adults in the household use? | Flush/pour flush |

| Flushed to piped sewer system | |

| Flushed to septic tank | |

| Flushed to pit latrine | |

| Flush to open drain | |

| Flush to unknown place | |

| Dry pit latrine | |

| Ventilated improved pit latrine | |

| Pit latrine with slab | |

| Pit latrine without slab /open pit | |

| Composting toilet | |

| Twin pit with slab | |

| Twin pit without slab | |

| Other composting toilet | |

| Bucket | |

| Container based sanitation | |

| Hanging toilet/hanging latrine | |

| No facility/Bush/Field | |

| Not able to access (only select if you are unable to observe private latrine) | |

| Other ___________ | |

| Whom do you share the defecation facility with? | Shared with known households |

| Shared with general public | |

| How many households in total use this toilet facility, including your own household? [Ngiyay ngikenoi dadang kekimar istiyaete ecoron lo ke ko keno dang?] | |

| Ask to see the toilet/latrine. Observe: What kind of toilet facility do the adults in the household use? | Flush/pour flush |

| Flushed to piped sewer system | |

| Flushed to septic tank | |

| Flushed to pit latrine | |

| Flush to open drain | |

| Flush to unknown place | |

| Dry pit latrine | |

| Ventilated improved pit latrine | |

| Pit latrine with slab | |

| Pit latrine without slab /open pit | |

| Composting toilet | |

| Twin pit with slab | |

| Twin pit without slab | |

| Other composting toilet | |

| Bucket | |

| Container based sanitation | |

| Hanging toilet/hanging latrine | |

| No facility/Bush/Field | |

| Not able to access (only select if you are unable to observe private latrine) | |

| Other ___________ | |

| Where is this toilet facility located? [Lowai ali eyayi echoron lo?] | In own dwelling |

| In own yard | |

| Elsewhere ___________ | |

| Has your (pit latrine or septic tank) ever been emptied? [Ikwa ekon coron ekatkintere akibuka?] | Yes |

| No | |

| Don’t know | |

| The last time it was emptied who did it? | Service provider |

| Household | |

| Other | |

| Don’t know | |

| The last time it was emptied, where were the contents emptied to? [Apak ngina abukitere ay aponi ngacin tobukokinai?] | To a treatment plant |

| Buried in a covered pit | |

| Don’t know | |

| Do all household members usually use the sanitation facility? [Istiyate dadang ngikenoi ecoron loa?] | Yes |

| No | |

| Is everyone in the household able to access and use the toilet at all times of the day and night? [Epedorito ngitunga dadang alokeno kon arukar ka akistia ecoron ngthai dadangia akitodol naparan ka akuwaria?] | Yes |

| No | |

| Do you or other household members face any risks when using the toilet? [Eyayi iyong kori iche alokenokon eriamunit adio munara alotoma akistia echoronia?] | No risks faced |

| Yes, risk to health | |

| Yes, risk of harassment | |

| Yes, other __________ | |

| Can you please show me where members of your household most often wash their hands? | Fixed facility in dwelling |

| Fixed facility in yard | |

| Mobile object (bucket, jug, kettle) | |

| No handwashing facility | |

| No permission to see | |

| Other reason ___________ | |

| Observation: Is there a hand washing facility in the yard/plot/premises? [Eyeyi ne ibore ngini ilotanarere iith ngkania?] | Yes |

| No | |

| Within 15 m of the latrine/toilet? [Alotoma ngadakikai 15 alotoma ecoronia?] | Yes |

| No | |

| Observation: At the time of the visit, is water available at the hand washing facility? [Alotoma etha ngolo edolio yong aya ngakipii ni bore nginikilothet ngakania?] | Yes |

| No | |

| Verify (opening the tap, water in the bucket etc.) [Towny(tonga atap, ngakipii alo baket kangunace.)] | Yes |

| No | |

| Observation: At the time of visit, is soap, detergent, or other cleaning agent available at the hand washing facility? [Alotoma etha ngolo idolitor yong ayeyia ethabunia neni ilothere ngakania?] | No |

| Yes, soap or detergent (in bar, liquid, or paste form) | |

| Yes, ash, mud, or sand | |

| When was the last time you washed your face? [Arai anipak ngna alwanan ilotaritor iyong eret kon?] | Today |

| Yesterday | |

| 2–6 days ago | |

| More than a week ago | |

| Don’t’ know | |

| On waking | |

| After breakfast | |

| Other __________ | |

| How often do you wash your face? [Ngaruwa ngai ilotanaria iiyong eret?] | More than twice a day |

| Two times a day | |

| Once a day | |

| Every other day | |

| Twice a week | |

| Once a week | |

| Once a month | |

| Less than once a month | |

| Other _________ | |

| Don’t know | |

| Where do the children sleep (same bed as the grown-ups)? [Ai eperete ngidwe (epei kitada ikwa papa ka totoa)?] | Yes |

| No | |

| How often do you wash the sheets? [Nkapakio anoo ilotanara iyong akon nangka?] | Every day |

| 2–3 times a week | |

| Once a week | |

| Twice a month | |

| Once a month | |

| Less than once a month | |

| Other __________ | |

| Don’t know | |

| Do you wash your hands after urinating? | Yes |

| No | |

| Do you wash your hands after defecating? | Yes |

| No | |

| Do you wash your hands after handling children’s faeces? | Yes |

| No |

Appendix D. Full Summary of Questionnaire Results

Table A1.

Full summary of the questionnaire results.

Table A1.

Full summary of the questionnaire results.

| Question | N Households (n = 30) (%) |

|---|---|

| Mass drug administration in last round | 21 (70) |

| Households with children under 3 years | 24 (80) |

| Borehole for drinking water source | 27 (90) |

| Public pipe for drinking water source | 3 (10) |

| Water source within 30-min return journey | 9 (30) |

| Lack of water the last month | 27 (90) |

| Children sleeping in the same bed as adults | 28 (93.3) |

| Drinking water acceptable | |

| Yes | 27 (90) |

| No, taste | 1 (3.3) |

| No, colour | 1 (3.3) |

| No, other | 1 (3.3) |

| Action to make drinking water safe | |

| Nothing | 27 (90) |

| Boil | 1 (3.3) |

| Strain through cloth | 1 (3.3) |

| Let it stand and settle | 1 (3.3) |

| Disposal of children’s faeces | |

| Disposal by putting it into a latrine | 2 (6.7) |

| Disposal by burying it | 16 (53.3) |

| Disposal by leaving it in the open | 6 (20) |

| Disposal by other | 6 (20 |

| Defecation site for adults | |

| Latrine without a slab | 2 (6.6) |

| No structure | 28 (93.3) |

| Face washing frequency | |

| Today | 28 (96.6)1 |

| More than twice a day | 13 (43) |

| Two times a day | 12 (40) |

| Once a day | 3 (10) |

| Other | 2 (6.7) |

| Handwashing facility | |

| Handwashing facility as mobile object | 30 (100) |

| Presence of handwashing facility | 1 (3.3) |

| Presence of water in the handwashing facility | 1 (100) |

| Presence of soap at the handwashing facility | 0 (0) |

| Handwashing | |

| Handwashing after defecation | 24 (82.8) 1 |

| Handwashing after urination | 13 (44.5) 1 |

| Handwashing after handling children’s faeces | 25 (89.3) 2 |

| Frequency of washing of bedsheets | |

| 2–3 times a week | 6 (20) |

| Once a week | 13 (43.3) |

| Twice a month | 4 (13.3) |

| Once a month | 6 (20) |

| Other | 1 (3.3) |

1 One missing value. 2 Two missing values.

References

- United Nations. General Assembly. The Human Right to Water and Sanitation. GA Res 64/292 2010, UN Doc A/Res/64/292. Available online: https://digitallibrary.un.org/record/687002 (accessed on 3 December 2022).

- United Nations. General comment no. 15: The right to water (arts. 11 and 12 of the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights). Agenda 2003, 11, 29. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. Ending the Neglect to Attain the Sustainable Development Goals: A Road Map for Neglected Tropical Diseases 2021–2030; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2020; p. 196. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization; Neglected Tropical Disease NGO Network. WASH and Health Working Together: A ‘How to’ Guide for Neglected Tropical Disease Programmes; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2018; p. 270. [Google Scholar]

- Emerson, L.E.; Anantharam, P.; Yehuala, F.M.; Bilcha, K.D.; Tesfaye, A.B.; Fairley, J.K. Poor WASH (Water, Sanitation, and Hygiene) Conditions Are Associated with Leprosy in North Gondar, Ethiopia. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 6061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strunz, E.C.; Addiss, D.G.; Stocks, M.E.; Ogden, S.; Utzinger, J.; Freeman, M.C. Water, sanitation, hygiene, and soil-transmitted helminth infection: A systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS Med. 2014, 11, e1001620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- WHO/UNICEF. JMP Methodology: 2017 Update & SDG Baselines. 2017. Available online: https://washdata.org/report/jmp-methodology-2017-update (accessed on 26 November 2022).

- United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF); World Health Organization. Core Questions on Drinking Water, Sanitation and Hygiene for Household Surveys; United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF) and World Health Organization: New York, NY, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF); World Health Organization. Core Questions and Indicators for Monitoring WASH in Schools in the Sustainable Development Goals; UNICEF and World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF); World Health Organization. Core Questions and Indicators for Monitoring WASH in Health Care Facilities in the Sustainable Development Goals; World Health Organization and the United Nations Children’s Fund: Geneva, Switzerland, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Jeanes, A.; Coen, P.G.; Gould, D.J.; Drey, N.S. Validity of hand hygiene compliance measurement by observation: A systematic review. Am. J. Infect. Control 2019, 47, 313–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barker, K.N. Data Collection Techniques: Observation. Am. J. Hosp. Pharm. 1980, 37, 1235–1245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bentley, M.E.; Boot, M.T.; Gittelsohn, J.; Stallings, R.Y. The Use of Structured Observations in the Study of Health Behaviour; IRC International Water and Sanitation Centre and London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine: The Hague, The Netherlands, 1994; Volume 27. [Google Scholar]

- Spencer, E.A.; Mahtani, K. Hawthorne Effect. Available online: https://catalogofbias.org/biases/hawthorne-effect/ (accessed on 4 January 2023).

- Manun’Ebo, M.; Cousens, S.; Haggerty, P.; Kalengaie, M.; Ashworth, A.; Kirkwood, B. Measuring hygiene practices: A comparison of questionnaires with direct observations in rural Zaïre. Trop. Med. Int. Health 1997, 2, 1015–1021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ram, P. Practical Guidance for Measuring Handwashing Behavior. Water and Sanitation Program: Working Paper; World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2010; Available online: https://openknowledge.worldbank.org/handle/10986/19005 (accessed on 2 December 2022).

- Greenland, K.; White, S.; Sommers, K.; Biran, A.; Burton, M.J.; Sarah, V.; Alemayehu, W. Selecting behaviour change priorities for trachoma ‘F’ and ‘E’ interventions: A formative research study in Oromia, Ethiopia. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 2019, 13, e0007784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tidwell, J.B.; Fergus, C.; Gopalakrishnan, A.; Sheth, E.; Sidibe, M.; Wohlgemuth, L.; Jain, A.; Woods, G. Integrating Face Washing into a School-Based, Handwashing Behavior Change Program to Prevent Trachoma in Turkana, Kenya. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 2019, 101, 767–773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Solomon, A.W.; Burton, M.J.; Gower, E.W.; Harding-Esch, E.M.; Oldenburg, C.E.; Taylor, H.R.; Traoré, L. Trachoma. Nat. Rev. Dis. Primers 2022, 8, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Last, A.; Versteeg, B.; Shafi Abdurahman, O.; Robinson, A.; Dumessa, G.; Abraham Aga, M.; Shumi Bejiga, G.; Negussu, N.; Greenland, K.; Czerniewska, A.; et al. Detecting extra-ocular Chlamydia trachomatis in a trachoma-endemic community in Ethiopia: Identifying potential routes of transmission. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 2020, 14, e0008120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Versteeg, B.; Vasileva, H.; Houghton, J.; Last, A.; Shafi Abdurahman, O.; Sarah, V.; Macleod, D.; Solomon, A.W.; Holland, M.J.; Thomson, N.; et al. Viability PCR shows that non-ocular surfaces could contribute to transmission of Chlamydia trachomatis infection in trachoma. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 2020, 14, e0008449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miller, K. Pesky trachoma suspect finally caught. Br. J. Opthalmol. 2004, 88, 750–751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emerson, P.M.; Lindsay, S.W.; Alexander, N.; Bah, M.; Dibba, S.M.; Faal, H.B.; Lowe, K.O.; McAdam, K.P.; Ratcliffe, A.A.; Walraven, G.E.; et al. Role of flies and provision of latrines in trachoma control: Cluster-randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2004, 363, 1093–1098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garn, J.V.; Boisson, S.; Willis, R.; Bakhtiari, A.; Al-Khatib, T.; Amer, K.; Batcho, W.; Courtright, P.; Dejene, M.; Goepogui, A.; et al. Sanitation and water supply coverage thresholds associated with active trachoma: Modeling cross-sectional data from 13 countries. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 2018, 12, e0006110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sullivan, K.M.; Harding-Esch, E.M.; Keil, A.P.; Freeman, M.C.; Batcho4, W.E.; Issifou, A.A.B.; Bucumi, V.; Assumpta, B.L.; Epee, E.; Barkesa, S.B.; et al. Exploring water, sanitation, and hygiene coverage targets for reaching and sustaining trachoma elimination: G-computation analysis. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 2023, 17, e0011103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Francis, V.; Turner, V.; WHO Programme for the Prevention of Blindness. Achieving Community Support for Trachoma Control: A Guide for District Health Work/Victoria Francis and Virginia Turner; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Kuper, H.; Solomon, A.W.; Buchan, J.; Zondervan, M.; Foster, A.; Mabey, D. A critical review of the SAFE strategy for the prevention of blinding trachoma. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2003, 3, 372–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Renneker, K.K.; Abdala, M.; Addy, J.; Al-Khatib, T.; Amer, K.; Badiane, M.D.; Batcho, W.; Bella, L.; Bougouma, C.; Bucumi, V.; et al. Global progress toward the elimination of active trachoma: An analysis of 38 countries. Lancet Glob. Health 2022, 10, e491–e500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baayenda, G.; Mugume, F.; Turyaguma, P.; Tukahebwa, E.M.; Binagwa, B.; Onapa, A.; Agunyo, S.; Osilo, M.K.; French, M.D.; Thuo, W.; et al. Completing Baseline Mapping of Trachoma in Uganda: Results of 14 Population-Based Prevalence Surveys Conducted in 2014 and 2018. Ophthalmic Epidemiol. 2018, 25, 162–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flueckiger, R.M.; Courtright, P.; Abdala, M.; Abdou, A.; Abdulnafea, Z.; Al-Khatib, T.K.; Amer, K.; Amiel, O.N.; Awoussi, S.; Bakhtiari, A.; et al. The global burden of trichiasis in 2016. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 2019, 13, e0007835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. WHO Alliance for the Global Elimination of Trachoma: Progress Report on Elimination of Trachoma, 2021; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2022; pp. 353–364. [Google Scholar]

- Ministry of Health; Vector Control Division. Beating Neglected Tropical Diseases in Uganda through Multi-Sector Action on Water, Sanitation and Hygiene—A National Framework; Ministry of Health; Vector Control Division: Kampala, Uganda, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Ministry of Health. Annual Health Sector Performance Report, Financial Year 2020/21; Ministry of Health: Kampala, Uganda, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. Informal Consultation on End-Game Challenges for Trachoma Elimination, Task Force for Global Health Decatur, United States of America, 7–9 December 2021; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Courtright, P.; MacArthur, C.; Macleod, C.; Dejene, M.; Gass, K.; Harding-Esch, E.; Jimenez, C.; Lewallen, S.; Mpyet, C.; Pavluck, A.; et al. Tropical Data: Training System for Trachoma Prevalence Surveys; International Coalition for Trachoma Control: London, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Kingsley, H. Administrative practice: New meanings through unstructured observational studies. J. Educ. Adm. 2000, 38, 288–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aunger, R.; White, S.; Greenland, K.; Curtis, V. Behaviour Centred Design: A Practitioner’s Manual; London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine: London, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Greenland, K.; Czerniewska, A.; Guye, M.; Legesse, D.; Ahmed Mume, A.; Shafi Abdurahman, O.; Abraham Aga, M.; Miecha, H.; Shumi Bejiga, G.; Sarah, V.; et al. Seasonal variation in water use for hygiene in Oromia, Ethiopia, and its implications for trachoma control: An intensive observational study. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 2022, 16, e0010424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guloba, D.M.K.; Miriam Ssewanyana, D.S.; Ahikire, P.J.; Musiimenta, D.P.; Boonabaana, D.B.; Ssennono, V. Gender Roles and the Care Economy in Ugandan Households the Case of Kaabong, Kabale and Kampala Districts; Oxfam: Kampala, Uganda, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Kanwar, R.; Grund, L.; Olson, J.C. When Do the Measures of Knowledge Measure What We Think They Are Measuring? Assoc. Consum. Res. 1990, 17, 603–608. [Google Scholar]

- R Core Team. A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing; R Foundation for Statistical Computing: Vienna, Austria, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual. Res. Psychol. 2006, 3, 77–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WHO; UNICEF. Sanitation. Available online: https://washdata.org/monitoring/sanitation#:~:text=The%20JMP%20ladder%20for%20sanitation,drinking%20water%2C%20sanitation%20and%20hygiene (accessed on 1 April 2022).

- The International Trachoma Initiative; Bastion Data. Trachoma Data. Available online: https://atlas.trachomadata.org/ (accessed on 2 January 2023).

- Ritchie, J.; Lewis, J.; Nicholls, C.M.; Ormston, R. Qualitative Research Practice: A Guide for Social Science Students and Researchers, 2nd ed.; SAGE publications Ltd.: London, UK, 2014; Volume 41, pp. 27–76. [Google Scholar]

- Eyoku, G. Over 500 Children in Nabilatuk Drop Out of School. Available online: https://ugandaradionetwork.net/story/over-500-children-in-nabilatuk-drop-out-of-school (accessed on 29 December 2022).

- Brown, V.; Kelly, M.; Mabugu, T. The Education System in Karamoja; HEART (High-Quality Technical Assistance for Results): Oxford, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Harding-Esch, E.M.; Holland, M.J.; Schémann, J.-F.; Sissoko, M.; Sarr, B.; Butcher, R.M.R.; Molina-Gonzalez, S.; Andreasen, A.A.; Mabey, D.C.W.; Bailey, R.L. Facial cleanliness indicators by time of day: Results of a cross-sectional trachoma prevalence survey in Senegal. Parasites Vectors 2020, 13, 556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aragie, S.; Wittberg, D.M.; Tadesse, W.; Dagnew, A.; Hailu, D.; Chernet, A.; Melo, J.S.; Aiemjoy, K.; Haile, M.; Zeru, T.; et al. Water, sanitation, and hygiene for control of trachoma in Ethiopia (WUHA): A two-arm, parallel-group, cluster-randomised trial. Lancet Glob. Health 2022, 10, e87–e95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ejere, H.O.; Alhassan, M.B.; Rabiu, M. Face washing promotion for preventing active trachoma. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2012, 4, CD003659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Evans, J.R.; Solomon, A.W.; Kumar, R.; Perez, Á.; Singh, B.P.; Srivastava, R.M.; Harding-Esch, E. Antibiotics for trachoma. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2019, 9, Cd001860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bilchut, A.H.; Burroughs, H.R.; Oldenburg, C.E.; Lietman, T.M. Trachoma Control: A Glass Half Full? Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 2023. ahead of print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Uganda (Karamoja): Acute Malnutrition Situation February–July 2022 and Projection for August–January 2023. Available online: https://www.ipcinfo.org/ipc-country-analysis/details-map/en/c/1155650/?iso3=UGA (accessed on 16 August 2022).

- Siddiqui, F.; Salam, R.A.; Lassi, Z.S.; Das, J.K. The Intertwined Relationship Between Malnutrition and Poverty. Front. Public Health 2020, 8, 453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kerpel-Fronius, E. The main causes of death in malnutrition. Acta Paediatr. Hung. 1984, 25, 127–130. [Google Scholar]

- Habtamu, E.; Wondie, T.; Aweke, S.; Tadesse, Z.; Zerihun, M.; Zewdie, Z.; Callahan, K.; Emerson, P.M.; Kuper, H.; Bailey, R.L.; et al. Trachoma and Relative Poverty: A Case-Control Study. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 2015, 9, e0004228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- United Nations. Transforming Our World: The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development; A/RES/70/1; United Nations: New York, NY, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Naiga, R.; Penker, M.; Hogl, K. Challenging pathways to safe water access in rural Uganda: From supply to demand-driven water governance. Int. J. Commons 2015, 9, 237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tamene, A.; Afework, A. Exploring barriers to the adoption and utilization of improved latrine facilities in rural Ethiopia: An Integrated Behavioral Model for Water, Sanitation and Hygiene (IBM-WASH) approach. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0245289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).