Sleep Hygiene Practices: Where to Now?

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Sleep Hygiene Practices

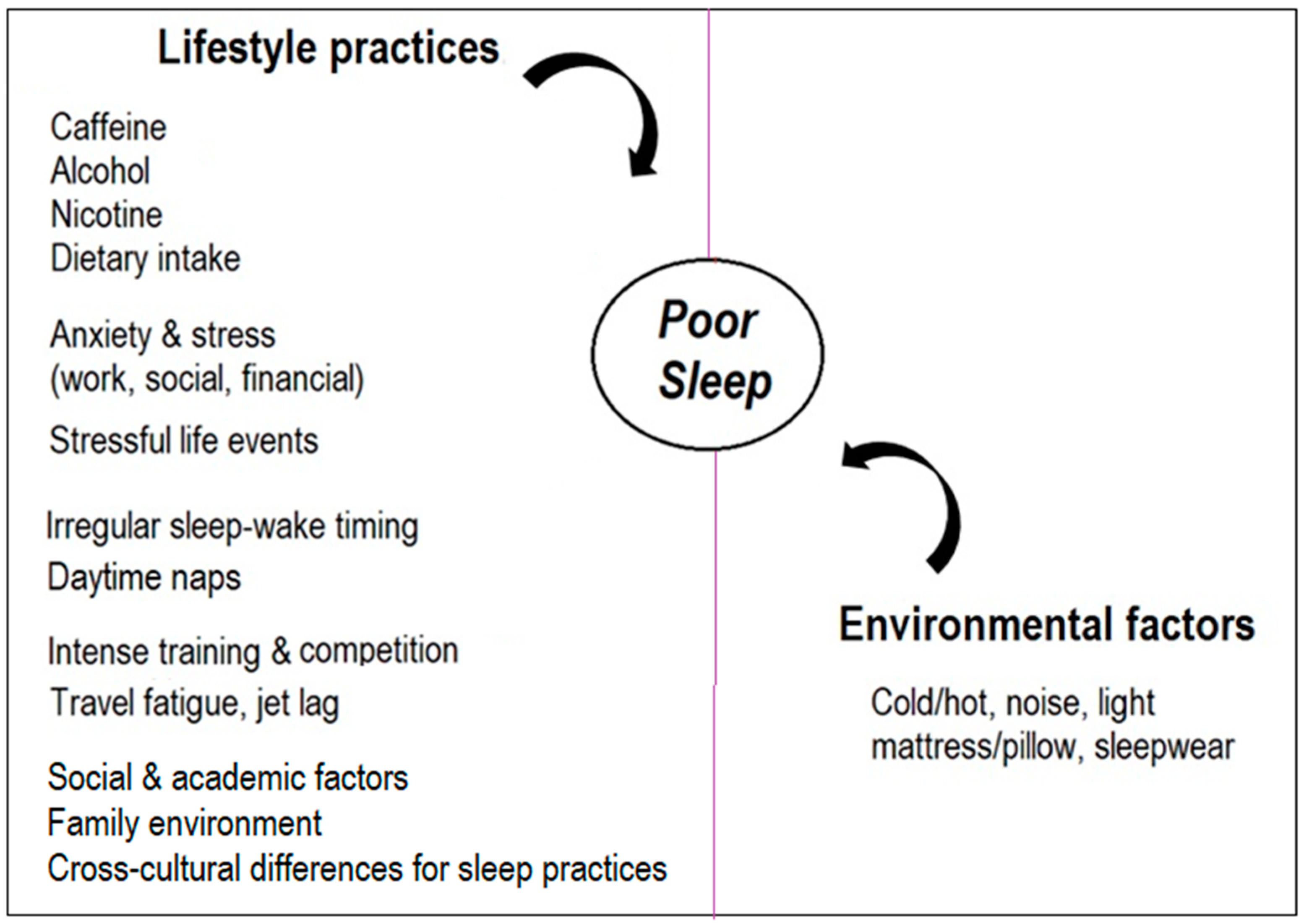

3. Sleep Hygiene Programs in Non-Clinical Populations

4. Precipitating Factors for Poor Sleep Are Unique to Individuals

5. Precision Medicine Approach to Sleep Hygiene

6. Conclusions and Recommendations

- the regularity of timing of rise time;

- morning light exposure and exercise for easy transition to sleep and sleep maintenance;

- strategies that manage negative emotions at bedtime;

- establishing high GI carbohydrates or tryptophan-rich foods for ease of sleep onset following intense training/competition in athletes.

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Borbély, A.A. A two process model of sleep regulation. Hum. Neurobiol. 1982, 1, 195–204. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Achermann, P. The two-process model of sleep regulation revisited. Aviat. Space Environ. Med. 2004, 75, A37–A43. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Bodziony, V.; Stetson, B. Associations between sleep, physical activity, and emotional well-being in emerging young adults: Implications for college wellness program development. J. Am. Coll. Health 2022, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferrie, J.E.; Shipley, M.J.; Akbaraly, T.N.; Marmot, M.G.; Kivimäki, M.; Singh-Manoux, A. Change in sleep duration and cognitive function: Findings from the Whitehall II Study. Sleep 2011, 34, 565–573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hauri, P. Sleep Hygiene, in Current Concepts: The Sleep Disorders; The Upjohn Company: Kalamazoo, MI, USA, 1977; pp. 21–35. [Google Scholar]

- Hauri, P.J. Sleep Hygiene, Relaxation Therapy, and Cognitive Interventions, in Case Studies in Insomnia; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 1991; pp. 65–84. [Google Scholar]

- Chow, C.M. Sleep and Wellbeing, Now and in the Future; Multidisciplinary Digital Publishing Institute: Basel, Switzerland, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Christensen, M.; Bettencourt, L.; Kaye, L.; Moturu, S.T.; Nguyen, K.T.; Olgin, J.E.; Pletcher, M.J.; Marcus, G.M. Direct measurements of smartphone screen-time: Relationships with demographics and sleep. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0165331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Twenge, J.M.; Hisler, G.C.; Krizan, Z. Associations between screen time and sleep duration are primarily driven by portable electronic devices: Evidence from a population-based study of US children ages 0–17. Sleep Med. 2019, 56, 211–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caddick, Z.A.; Gregory, K.; Arsintescu, L.; Flynn-Evans, E.E. A review of the environmental parameters necessary for an optimal sleep environment. Build. Environ. 2018, 132, 11–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okamoto-Mizuno, K.; Mizuno, K. Effects of thermal environment on sleep and circadian rhythm. J. Physiol. Anthropol. 2012, 31, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chow, C.M.; Shin, M.; Mahar, T.J.; Halaki, M.; Ireland, A. The impact of sleepwear fiber type on sleep quality under warm ambient conditions. Nat. Sci. Sleep 2019, 11, 167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gipson, C.S.; Chilton, J.M.; Dickerson, S.S.; Alfred, D.; Haas, B.K. Effects of a sleep hygiene text message intervention on sleep in college students. J. Am. Coll. Health 2019, 67, 32–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carskadon, M.A. Factors influencing sleep patterns of adolescents. In Adolescent Sleep Patterns: Biological, Social, and Psychological Influences; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2002; pp. 4–26. [Google Scholar]

- Billows, M.; Gradisar, M.; Dohnt, H.; Johnston, A.; McCappin, S.; Hudson, J. Family disorganization, sleep hygiene, and adolescent sleep disturbance. J. Clin. Child Adolesc. Psychol. 2009, 38, 745–752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jeon, M.; Dimitriou, D.; Halstead, E.J. A systematic review on cross-cultural comparative studies of sleep in young populations: The roles of cultural factors. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 2005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Sousa, I.C.; Araújo, J.F.; De Azevedo, C.V.M. The effect of a sleep hygiene education program on the sleep-wake cycle of Brazilian adolescent students. Sleep Biol. Rhythm. 2007, 5, 251–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Otsuka, Y.; Kaneita, Y.; Itani, O.; Tokiya, M. A school-based sleep hygiene education program for adolescents in Japan: A large-scale comparative intervention study. Sleep Biol. Rhythm. 2020, 18, 27–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kakinuma, M.; Takahashi, M.; Kato, N.; Aratake, Y.; Watanabe, M.; Ishikawa, Y.; Kojima, R.; Shibaoka, M.; Tanaka, K. Effect of brief sleep hygiene education for workers of an information technology company. Ind. Health 2010, 48, 758–765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vitale, J.A.; La Torre, A.; Banfi, G.; Bonato, M. Acute sleep hygiene strategy improves objective sleep latency following a late-evening soccer-specific training session: A randomized controlled trial. J. Sports Sci. 2019, 37, 2711–2719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caia, J.; Scott, T.J.; Halson, S.L.; Kelly, V.G. The influence of sleep hygiene education on sleep in professional rugby league athletes. Sleep Health 2018, 4, 364–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Ryswyk, E.; Weeks, R.; Bandick, L.; O’Keefe, M.; Vakulin, A.; Catcheside, P.; Barger, L.; Potter, A.; Poulos, N.; Wallace, J.; et al. A novel sleep optimisation programme to improve athletes’ well-being and performance. Eur. J. Sport Sci. 2017, 17, 144–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Donnell, S.; Driller, M.W. Sleep-hygiene education improves sleep indices in elite female athletes. Int. J. Exerc. Sci. 2017, 10, 522. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, P.-H.; Kuo, H.-Y.; Chueh, K.-H. Sleep hygiene education: Efficacy on sleep quality in working women. J. Nurs. Res. 2010, 18, 283–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dewald-Kaufmann, J.F.; Oort, F.; Meijer, A. The effects of sleep extension and sleep hygiene advice on sleep and depressive symptoms in adolescents: A randomized controlled trial. J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry 2014, 55, 273–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, C.-Y.; Strong, C.; Scott, A.J.; Broström, A.; Pakpour, A.H.; Webb, T.L. A cluster randomized controlled trial of a theory-based sleep hygiene intervention for adolescents. Sleep 2018, 41, zsy170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, F.C.; Jr, W.C.B.; Soper, B. Relationship of sleep hygiene awareness, sleep hygiene practices, and sleep quality in university students. Behav. Med. 2002, 28, 33–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamilton, K.; Ng, H.T.H.; Zhang, C.-Q.; Phipps, D.J.; Zhang, R. Social psychological predictors of sleep hygiene behaviors in Australian and Hong Kong university students. Int. J. Behav. Med. 2021, 28, 214–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shimura, A.; Sugiura, K.; Inoue, M.; Misaki, S.; Tanimoto, Y.; Oshima, A.; Tanaka, T.; Yokoi, K.; Inoue, T. Which sleep hygiene factors are important? comprehensive assessment of lifestyle habits and job environment on sleep among office workers. Sleep Health 2020, 6, 288–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheek, R.E.; Shaver, J.L.F.; Lentz, M.J. Variations in sleep hygiene practices of women with and without insomnia. Res. Nurs. Health 2004, 27, 225–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Murray, J.M.; Phillips, A.J.; Magee, M.; Sletten, T.; Gordon, C.; Lovato, N.; Bei, B.; Bartlett, D.J.; Kennaway, D.; Lack, L.C.; et al. Sleep regularity is associated with sleep-wake and circadian timing, and mediates daytime function in delayed sleep-wake phase disorder. Sleep Med. 2019, 58, 93–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Irish, L.A.; Kline, C.E.; Gunn, H.E.; Buysse, D.J.; Hall, M.H. The role of sleep hygiene in promoting public health: A review of empirical evidence. Sleep Med. Rev. 2015, 22, 23–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morin, C.M. Psychological and Behavioral Treatments for Insomnia I: Approaches and Efficacy, in Principles and Practice of Sleep Medicine; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2011; pp. 866–883. [Google Scholar]

- Roenneberg, T.; Kumar, C.J.; Merrow, M. The human circadian clock entrains to sun time. Curr. Biol. 2007, 17, R44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cajochen, C.; Münch, M.; Kobialka, S.; Kräuchi, K.; Steiner, R.; Oelhafen, P.; Orgül, S.; Wirz-Justice, A. High sensitivity of human melatonin, alertness, thermoregulation, and heart rate to short wavelength light. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2005, 90, 1311–1316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lockley, S.W.; Evans, E.E.; Scheer, F.; Brainard, G.C.; Czeisler, C.A.; Aeschbach, D. Short-wavelength sensitivity for the direct effects of light on alertness, vigilance, and the waking electroencephalogram in humans. Sleep 2006, 29, 161–168. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Thorne, H.C.; Jones, K.H.; Peters, S.P.; Archer, S.N.; Dijk, D.-J. Daily and seasonal variation in the spectral composition of light exposure in humans. Chronobiol. Int. 2009, 26, 854–866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schroder, E.A.; Esser, K.A. Circadian rhythms, skeletal muscle molecular clocks and exercise. Exerc. Sport Sci. Rev. 2013, 41, 224–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Youngstedt, S.D.; Kline, C.E.; Elliott, J.A.; Zielinski, M.R.; Devlin, T.M.; Moore, T.A. Circadian phase-shifting effects of bright light, exercise, and bright light+ exercise. J. Circadian Rhythm. 2016, 14, 2. [Google Scholar]

- Youngstedt, S.D.; Elliott, J.A.; Kripke, D.F. Human circadian phase–response curves for exercise. J. Physiol. 2019, 597, 2253–2268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kimberly, B.; James, R.P. Amber lenses to block blue light and improve sleep: A randomized trial. Chronobiol. Int. 2009, 26, 1602–1612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coyle, E.F. Timing and method of increased carbohydrate intake to cope with heavy training, competition and recovery. J. Sports Sci. 1991, 9, 29–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afaghi, A.; O’Connor, H.; Chow, C.M. High-glycemic-index carbohydrate meals shorten sleep onset. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2007, 85, 426–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, H.-H.; Tsai, P.-S.; Fang, S.-C.; Liu, J.-F. Effect of kiwifruit consumption on sleep quality in adults with sleep problems. Asia Pac. J. Clin. Nutr. 2011, 20, 169–174. [Google Scholar]

- Howatson, G.; Bell, P.G.; Tallent, J.; Middleton, B.; McHugh, M.P.; Ellis, J. Effect of tart cherry juice (Prunus cerasus) on melatonin levels and enhanced sleep quality. Eur. J. Nutr. 2012, 51, 909–916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brand-Miller, J.; Hayne, S.; Petocz, P.; Colagiuri, S. Low–glycemic index diets in the management of diabetes: A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Diabetes Care 2003, 26, 2261–2267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Whitworth-Turner, C.; Di Michele, R.; Muir, I.; Gregson, W.; Drust, B. A shower before bedtime may improve the sleep onset latency of youth soccer players. Eur. J. Sport Sci. 2017, 17, 1119–1128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Chow, C.M. Sleep Hygiene Practices: Where to Now? Hygiene 2022, 2, 146-151. https://doi.org/10.3390/hygiene2030013

Chow CM. Sleep Hygiene Practices: Where to Now? Hygiene. 2022; 2(3):146-151. https://doi.org/10.3390/hygiene2030013

Chicago/Turabian StyleChow, Chin Moi. 2022. "Sleep Hygiene Practices: Where to Now?" Hygiene 2, no. 3: 146-151. https://doi.org/10.3390/hygiene2030013

APA StyleChow, C. M. (2022). Sleep Hygiene Practices: Where to Now? Hygiene, 2(3), 146-151. https://doi.org/10.3390/hygiene2030013