Complementary Food Feeding Hygiene Practice and Associated Factors among Mothers with Children Aged 6–24 Months in Tegedie District, Northwest Ethiopia: Community-Based Cross-Sectional Study

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Area, Design, and Period

2.2. Study Population

2.3. Sample Size and Sampling Technique

2.4. Variable

2.4.1. Dependent Variable

2.4.2. Independent Variables

2.5. Operational Definition

2.6. Data Collection and Quality Control

2.7. Data Processing and Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Socio demographic Characteristics of Participants

3.2. Housing and Environmental Characteristics

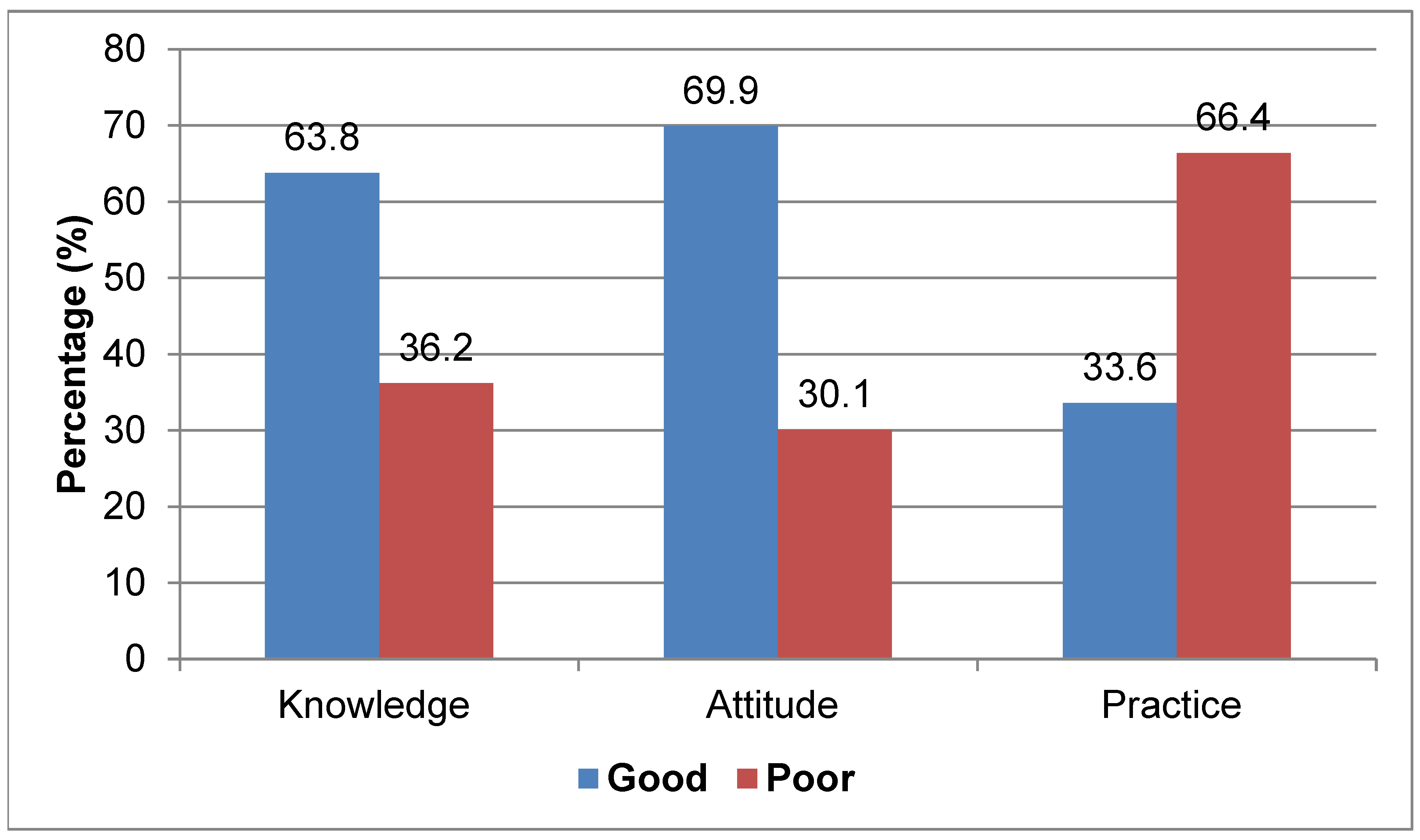

3.3. Knowledge, Attitude, and Practice of Hygienic Complementary Feeding

3.4. Factors Related to Hygienic Complementary Food Feeding Practices

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions and Recommendations

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AOR | adjusted odds ratio |

| CF | complementary feeding |

| COR | crude odds ratio |

| HEW | health extension worker |

| ETB | Ethiopian birr |

| HH | households |

| OD | open defecation |

| SPSS | Statistical Package for Social Sciences |

| WHO | World Health Organization |

References

- World Health Organization. Complementary Feeding: Report of the Global Consultation, and Summary of Guiding Principles for Complementary Feeding of the Breastfed Child; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Gautam, O. Food hygiene intervention to improve food hygiene behaviours, and reduce food contamination in Nepal: An exploratory trial. Lond. Sch. Hyg. Trop. Med. 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Jones, A.D.; Ickes, S.B.; Smith, L.E.; Mbuya, M.N.; Chasekwa, B.; Heidkamp, R.A.; Menon, P.; Zongrone, A.A.; Stoltzfus, R.J. World Health Organization infant and young child feeding indicators and their associations with child anthropometry: A synthesis of recent findings. Matern. Child Nutr. 2014, 10, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Das, S.; Fahim, S.M.; Alam, A.; Mahfuz, M.; Bessong, P.; Mduma, E.; Kosek, M.; Shrestha, S.K.; Ahmed, T. Not water, sanitation and hygiene practice, but timing of stunting is associated with recovery from stunting at 24 months: Results from a multi-country birth cohort study. Public Health Nutr. 2021, 24, 1428–1437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gizaw, Z.; Woldu, W.; Bitew, B.D. Child feeding practices and diarrheal disease among children less than two years of age of the nomadic people in Hadaleala District, Afar Region, Northeast Ethiopia. Int. Breastfeed. J. 2017, 12, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shati, A.A.; Khalil, S.N.; Asiri, K.A.; Alshehri, A.A.; Deajim, Y.A.; Al-Amer, M.S.; Alshehri, H.J.; Alshehri, A.A.; Alqahtani, F.S. Occurrence of Diarrhea and Feeding Practices among Children below Two Years of Age in Southwestern Saudi Arabia. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ehiri, J.E.; Azubuike, M.C.; Ubbaonu, C.N.; Anyanwu, E.C.; Ibe, K.M.; Ogbonna, M.O. Critical control points of complementary food preparation and handling in eastern Nigeria. Bull. World Health Organ. 2001, 79, 423–433. [Google Scholar]

- Mattioli, M.C.; Pickering, A.J.; Gilsdorf, R.J.; Davis, J.; Boehm, A.B. Hands and water as vectors of diarrheal pathogens in Bagamoyo, Tanzania. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2013, 47, 355–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oluwafemi, F.; Ibeh, I.N. Microbial contamination of seven major weaning foods in Nigeria. J. Health Popul. Nutr. 2011, 29, 415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Gorospe, E.C.; Oxentenko, A.S. Nutritional consequences of chronic diarrhoea. Best Pract. Res. Clin. Gastroenterol. 2012, 26, 663–675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Derso, T.; Tariku, A.; Biks, G.A.; Wassie, M.M. Stunting, wasting and associated factors among children aged 6–24 months in Dabat health and demographic surveillance system site: A community based cross-sectional study in Ethiopia. BMC Pediatrics 2017, 17, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Curtis, V.; Schmidt, W.; Luby, S.; Florez, R.; Touré, O.; Biran, A. Hygiene: New hopes, new horizons. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2011, 11, 312–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moss, C.; Bekele, T.H.; Salasibew, M.M.; Sturgess, J.; Ayana, G.; Kuche, D.; Eshetu, S.; Abera, A.; Allen, E.; Dangour, A.D. Sustainable Undernutrition Reduction in Ethiopia (SURE) evaluation study: A protocol to evaluate impact, process and context of a large-scale integrated health and agriculture programme to improvecomplementary feeding in Ethiopia. BMJ Open 2018, 8, e022028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arikpo, D.; Edet, E.S.; Chibuzor, M.T.; Odey, F.; Caldwell, D.M. Educational interventions for improving primary caregiver complementary feeding practices for children aged 24 months and under. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2018, 2018, CD011768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Bedada, S.; Tegegne, M.; Benti, T. Complementary Food Hygiene Practice among Mothers or Caregivers in Bale Zone, Southeast Ethiopia: A Community Based Cross-Sectional Study. J. Food Sci. Hyg. 2021, 1, 26. [Google Scholar]

- Bizzego, A.; Gabrieli, G.; Bornstein, M.H.; Deater-Deckard, K.; Lansford, J.E.; Bradley, R.H.; Costa, M.E.; Esposito, G. Predictors of Contemporary under-5 Child Mortality in Low-and Middle-Income Countries: A Machine Learning Approach. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 1315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mshida, H.A.; Kassim, N.; Mpolya, E.; Kimanya, M. Water, sanitation, and hygiene practices associated with nutritional status of under-five children in semi-pastoral communities Tanzania. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 2018, 98, 1242–1249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Manikam, L.; Robinson, A.; Kuah, J.Y.; Vaidya, H.J.; Alexander, E.C.; Miller, G.W.; Lakhanpaul, M. A systematic review of complementary feeding practices in South Asian infants and young children: The Bangladesh perspective. BMC Nutr. 2017, 3, 56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Byrd, K.; Williams, A.; Dentz, H.N.; Kiprotich, M.; Rao, G.; Arnold, C.D.; Stewart, C.P. Differences in complementary feeding practices within the context of the wash benefits randomized, controlled trial of nutrition, water, sanitation, and hygiene interventions in rural Kenya. FASEB J. 2017, 31, 165.1. [Google Scholar]

- Abdurahman, A.A.; Chaka, E.E.; Bule, M.H.; Niaz, K. Magnitude and determinants of complementary feeding practices in Ethiopia: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Heliyon 2019, 5, e01865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ntaji, M.I.; Oyibo, P.G.; Bamidele, J.O. Food hygiene practices of mothers of under-fives and prevalence of diarrhoea in their children in Malawi. J. Med. Biomed. Res. 2014, 13, 134–145. [Google Scholar]

- Rah, J.H.; Cronin, A.A.; Badgaiyan, B.; Aguayo, V.M.; Coates, S.; Ahmed, S. Household sanitation and personal hygiene practices are associated with child stunting in rural India: A cross-sectional analysis of surveys. BMJ Open 2015, 5, e005180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barker, J.; Stevens, D.; Bloomfield, S.F. Spread and prevention of some common viral infections in community facilities and domestic homes. J. Appl. Microbiol. 2001, 91, 7–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rockville, M. USA: EPHI Ethiopia Mini Demographic and Health Survey; Ethiopian Public Health Institute (EPHI): Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Zongrone, A.; Winskell, K.; Menon, P. Infant and young child feeding practices and child undernutrition in Bangladesh: Insights from nationally representative data. Public Health Nutr. 2012, 15, 1697-70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Dagne, A.H.; Anteneh, K.T.; Badi, M.B.; Adhanu, H.H.; Ahunie, M.A.; Aynalem, G.L. Appropriate complementary feeding practice and associated factors among mothers having children aged 6–24 months in Debre Tabor Hospital, North West Ethiopia,2016. BMC Res. Notes 2019, 12, 215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Mitchodigni, I.M.; Hounkpatin, W.A.; Ntandou-Bouzitou, G.; Avohou, H.; Termote, C.; Kennedy, G.; Hounhouigan, D.J. Complementary feeding practices: Determinants of dietary diversity and meal frequency among children aged 6–23 months in Southern Benin. Food Secur. 2017, 9, 1117–1130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Mohammed, S.; Tamiru, D. The burden of diarrheal diseases among children under five years of age in Arba Minch District, southern Ethiopia, and associated risk factors: A cross-sectional study. Int. Sch. Res. Not. 2014, 2014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Fufa, A.; Abhram, A.; Awgichew Teshome, K.T.; Abera, F.; MaledaTefera, M.Y.; Mengistu, M.; Egata, G. Hygienic Practice of Complementary Food Preparation and Associated Factors among Mothers with Children Aged from 6 to 24 Months in Rural Kebeles of Harari Region, Ethiopia. Food Sci. Technol. 2020, 8, 34–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agustina, R.; Sari, T.P.; Satroamidjojo, S.; Bovee-Oudenhoven, I.M.; Feskens, E.J.; Kok, F.J. Association of food-hygiene practices and diarrhea prevalence among Indonesian young children from low socioeconomic urban areas. BMC Public Health 2012, 13, 977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Yitayih, G.; Belay, K.; Tsegaye, M. Assessment of Hygienic Practice on Complementary Food among Mothers with 6–24 Months Age Living Young Children in Mohoni Town, North Eastern Ethiopia, 2015. J. Immunol. 2016, 6, 6–11. [Google Scholar]

- Afolabi, K.A.; Afolabi, A.O.; Omishakin, M.Y.J. Complementary feeding and associated factors: Assessing compliance with recommended guidelines among postpartum mothers in Nigeria. Popul. Med. 2021, 3, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molla, M.; Ejigu, T.; Nega, G. Complementary Feeding Practice and Associated Factors among Mothers Having Children 6–23 Months of Age, Lasta District, Amhara Region, Northeast Ethiopia. Adv. Public Health 2017, 2017, 4567829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Dagne, H.; Bogale, L.; Borcha, M.; Tesfaye, A.; Dagnew, B. Hand washing practice at critical times and its associated factors among mothers of under five children in Debark town, northwest Ethiopia, 2018. Ital. J. Pediatrics 2019, 45, 120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Demmelash, A.A.; Melese, B.D.; Admasu, F.T.; Bayih, E.T.; Yitbarek, G.Y. Hygienic Practice during Complementary Feeding and Associated Factors among Mothers of Children Aged 6–24 Months in Bahir Dar Zuria District, Northwest Ethiopia, 2019. J. Environ. Public Health 2020, 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akoma Okugn, D.W. Food hygiene practices and its associated factors among model and non model households in Abobo district, southwestern Ethiopia: Comparative cross-sectional study. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0194391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

| Variable/Categories | Frequency (n) | Percent (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Ethnicity | ||

| Amhara | 559 | 97.7 |

| Tigray | 8 | 1.4 |

| Others * | 5 | 0.9 |

| Religion | ||

| Orthodox | 488 | 85.3 |

| Muslim | 78 | 13.6 |

| Catholic | 2 | 0.3 |

| Others ** | 4 | 0.7 |

| Maternal educational status | ||

| No formal education | 345 | 60.3 |

| Primary level | 81 | 14.2 |

| Secondary level | 58 | 10.1 |

| Diploma and above | 88 | 15.4 |

| Maternal occupation | ||

| Civil servant | 88 | 15.4 |

| Merchant | 52 | 9.1 |

| Unemployed | 64 | 11.2 |

| Daily laborer | 38 | 6.6 |

| Housewife | 329 | 57.5 |

| Student | 1 | 0.2 |

| Marital status of mothers | ||

| Married | 519 | 90.7 |

| Lives separately | 4 | 0.7 |

| Single | 9 | 1.6 |

| Divorced | 31 | 5.4 |

| Widowed | 9 | 1.6 |

| Husband’s educational status (N = 523) | ||

| Diploma and above | 105 | 20.1 |

| Secondary level | 68 | 13.0 |

| Primary level | 151 | 28.9 |

| No formal education | 199 | 38.0 |

| Husband’s occupational status (N = 523) | ||

| Civil servant | 109 | 20.8 |

| Merchant | 166 | 31.7 |

| Unemployed | 9 | 1.7 |

| Daily laborer | 66 | 12.6 |

| Farmer | 173 | 33.1 |

| Family size | ||

| Fewer than 5 | 338 | 59.1 |

| 5 and above | 234 | 40.9 |

| No. of children under 2 | ||

| One | 551 | 96.3 |

| More than 1 | 21 | 3.7 |

| Household monthly income | ||

| Mean and above(2756.65) | 249 | 43.5 |

| Below mean | 323 | 56.5 |

| Place of residence | ||

| Urban | 374 | 65.4 |

| Rural | 198 | 34.6 |

| Access to media (TV or radio) | ||

| Yes | 288 | 50.3 |

| No | 284 | 49.7 |

| Got training on child food preparation | ||

| Yes | 85 | 14.9 |

| No | 487 | 85.1 |

| Variable/Categories | Frequency (n) | Percent (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Presence of latrine | ||

| Yes | 482 | 84.3 |

| No | 90 | 15.7 |

| Type of latrine | ||

| Pour flush | 21 | 3.7 |

| VIP latrine | 118 | 20.6 |

| Pit latrine with slab | 239 | 41.8 |

| Pit latrine without slab | 105 | 18.4 |

| No latrine facilities | 89 | 15.6 |

| Presence of handwashing facility near the latrine | ||

| Yes | 29 | 5.1 |

| No | 543 | 94.9 |

| Handwashing with soap after visiting toilets | ||

| Always | 274 | 47.9 |

| Sometimes | 93 | 16.3 |

| Never | 205 | 35.8 |

| Handwashing with soap after cleaning child’s bottom | ||

| Always | 276 | 48.3 |

| Sometimes | 91 | 15.9 |

| Wash only with water | 186 | 32.5 |

| Never | 19 | 3.3 |

| Wash child’s hands with soap after he/she defecates | ||

| Always | 308 | 53.8 |

| Sometimes | 158 | 27.6 |

| Wash only with water | 106 | 18.5 |

| Source of drinking water | ||

| Protected water | 561 | 98.1 |

| Unprotected water | 11 | 1.9 |

| Distance to the water source | ||

| In the yard | 185 | 32.3 |

| ≤30 min | 196 | 34.3 |

| >30 min | 191 | 33.4 |

| HH water treatment | ||

| Yes | 62 | 10.8 |

| No | 510 | 89.2 |

| Presence of separate kitchen for food preparation | ||

| Yes | 510 | 89.2 |

| No | 62 | 10.8 |

| Type of cook stove | ||

| Modern stove | 192 | 33.6 |

| Cultural stove | 380 | 66.4 |

| Presence of separate area to store raw and cooked foods | ||

| Yes | 375 | 65.6 |

| No | 197 | 34.4 |

| Presence of a three-compartment dishwashing facility | ||

| Yes | 266 | 46.5 |

| No | 306 | 53.5 |

| Knowledge | ||

| Good (mean and above) | 365 | 63.8 |

| Poor (below mean) | 207 | 36.2 |

| Attitude | ||

| Good attitude | 400 | 69.9 |

| Poor attitude | 172 | 30.1 |

| Variable/Categories | Complementary Feeding Hygienic Practices | COR(95% CI) | AOR (95% CI) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Good | Poor | |||

| Maternal education | ||||

| Diploma and above | 53 | 35 | 1 | |

| Secondary level | 20 | 38 | 0.35 (1.44, 5.73) ** | |

| Primary level | 24 | 57 | 0.28 (1.90, 6.82) *** | |

| No formal education | 95 | 250 | 0.25(2.45, 6.49) *** | |

| Place of residence | ||||

| Urban | 165 | 209 | 5.00 (3.17, 7.88) *** | 7.02 (4.14, 11.88) *** |

| Rural | 27 | 171 | 1 | 1 |

| Access to media (TV or radio) | ||||

| Yes | 132 | 156 | 3.16 (2.19, 4.56) *** | |

| No | 60 | 224 | 1 | |

| Presence of latrine | ||||

| Yes | 175 | 307 | 2.45 (1.40, 4.28) ** | |

| No | 17 | 73 | 1 | |

| Type of latrine | ||||

| Improved | 151 | 227 | 2.48(1.66, 3.71) *** | |

| Unimproved | 41 | 153 | 1 | |

| Time taken to reach the water source | ||||

| ≤30 min | 147 | 234 | 2.04(1.38, 3.02) *** | |

| >30 min | 45 | 146 | 1 | |

| HH water treatment | ||||

| Yes | 27 | 35 | 1.61 (0.94, 2.76) | |

| No | 165 | 345 | 1 | |

| Presence of handwashing facility near the latrine | ||||

| Yes | 20 | 9 | 4.79 (2.14, 10.75) *** | 3.02 (1.18, 7.70) * |

| No | 172 | 371 | 1 | 1 |

| Separate kitchen for food preparation | ||||

| Yes | 187 | 323 | 6.60 (2.60, 16.76) *** | |

| No | 5 | 57 | 1 | |

| Presence of separate area to store raw and cooked foods | ||||

| Yes | 181 | 194 | 15.78(8.31, 29.95) *** | 5.87 (2.84, 12.13) *** |

| No | 11 | 186 | 1 | 1 |

| Presence of three-compartment dishwashing facility | ||||

| Yes | 149 | 117 | 7.79 (5.21, 11.66) *** | 5.70 (3.41, 9.54) *** |

| No | 43 | 263 | 1 | 1 |

| Knowledge | ||||

| Good | 142 | 223 | 2.00 (1.37, 2.93) *** | |

| Poor | 50 | 157 | 1 | |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Teshome, H.A.; Yallew, W.W.; Mulualem, J.A.; Engdaw, G.T.; Zeleke, A.M. Complementary Food Feeding Hygiene Practice and Associated Factors among Mothers with Children Aged 6–24 Months in Tegedie District, Northwest Ethiopia: Community-Based Cross-Sectional Study. Hygiene 2022, 2, 72-84. https://doi.org/10.3390/hygiene2020006

Teshome HA, Yallew WW, Mulualem JA, Engdaw GT, Zeleke AM. Complementary Food Feeding Hygiene Practice and Associated Factors among Mothers with Children Aged 6–24 Months in Tegedie District, Northwest Ethiopia: Community-Based Cross-Sectional Study. Hygiene. 2022; 2(2):72-84. https://doi.org/10.3390/hygiene2020006

Chicago/Turabian StyleTeshome, Habtam Ayenew, Walelegn Worku Yallew, Jember Azanaw Mulualem, Garedew Tadege Engdaw, and Agerie Mengistie Zeleke. 2022. "Complementary Food Feeding Hygiene Practice and Associated Factors among Mothers with Children Aged 6–24 Months in Tegedie District, Northwest Ethiopia: Community-Based Cross-Sectional Study" Hygiene 2, no. 2: 72-84. https://doi.org/10.3390/hygiene2020006

APA StyleTeshome, H. A., Yallew, W. W., Mulualem, J. A., Engdaw, G. T., & Zeleke, A. M. (2022). Complementary Food Feeding Hygiene Practice and Associated Factors among Mothers with Children Aged 6–24 Months in Tegedie District, Northwest Ethiopia: Community-Based Cross-Sectional Study. Hygiene, 2(2), 72-84. https://doi.org/10.3390/hygiene2020006