Abstract

This article studies and provides a narrative review of the history of the native Orang Kallang people residing on Singapore’s Kallang River before Singapore’s modernization. The first section delves into the Orang Laut and how a group of them moved to the Kallang River to form the independent tribe of the Orang Kallang. This is followed by the historical significance of the Kallang River and its role in trade and maritime commerce in early Singapore. Subsequently, the second section investigates the Orang Kallang’s origins, livelihood, language, and reasons for their eventual decline. As the Orang Kallang tribe split after the arrival of the British in 1819, the group that settled in Pulai River, Johor, was recorded to have dwindled staggeringly in population due to a smallpox epidemic. The third section will focus on the impact of smallpox on the early aboriginal populations of Singapore (and the overarching region of Malaya), failed vaccination attempts, and how the Orang Kallang was likely to have been impacted. The last section will sum up the themes discussed in the paper.

1. Background

1.1. The Orang Kallang as Part of the Orang Laut Tribe

The Orang Biduanda Kallang, or ‘Orang Kallang’, was a subset of the Orang Laut (‘Sea People’) tribe, a group of sea-based nomads that were the native inhabitants of the land of modern-day Singapore. The term ‘Orang Laut’ collectively refers to the nomad sea communities living in the northern and southern entrances to the Straits of Melaka, parts of Sumatra and the Malay Peninsula, the Riau-Lingga archipelagoes, and island clusters in the South China Sea [1,2]. Information on the origins, history and livelihood of the early Orang Laut is sparse due to the lack of documentation and records kept by the tribes. Scholars believe their presence in the region dates back at least the 14th and 15th centuries. Existing documentation came from other communities that traveled to the region for trade or exploration. 15th-century records from Chinese and Arab traders depict a largely negative picture of the Orang Laut, often labeling them as cruel pirates that were widely feared by sea travelers [3]. One of the first existing western accounts is from Portuguese apothecary Tomé Pires in his work ‘Suma Oriental’ written between 1512–1515. He refers to the ‘sea people’, implied to be the Orang Laut, as Celates [4]. Although he describes the Celates as raiders that operated in the Straits, he noted that they did maintain a strong relationship with the local rulers and were obedient to Malacca by serving as rowers and assisting with trade. In turn, they were rewarded in the form of food supply from the King of Malacca. Their loyalty was key in ensuring the King’s power and control over trade in the region, expanding on trading patterns established by his predecessor, Srivijaya [4].

The Orang Laut’s sea-faring prowess significantly shaped the region’s political history, such as boosting trade in the Srivijaya Empire from the 7th to the late 14th century [5]. According to Portuguese sources, the Orang Laut, in 1391, assisted and guarded the Palembang Prince Parameswara as he sought refuge in Singapore [4] (p. 37). Parameswara (or Iskandar Shah) would go on to form the trading Sultanate, Melaka (Malacca), which led to an economic boom, the spread and development of the Malay language, and the region’s cultural arts and literature, marking the golden age of the Malay sultanates [6]. The Orang Laut retained close relations with the region’s rulers, persisting after the Portuguese colonization of the area in 1511 and British colonization in 1819 [4]. The British describe the Orang Laut as living ‘simple’ nomad lives in small familial groups in canoes upon the rivers. Many followed either pagan beliefs or a superficial form of Mohammedanism, and their livelihood was centered on activities like fishing or collecting aquatic materials [7].

The Orang Laut, though prominent, was mainly non-homogenous. Individual tribes were formed in different hydrogeographic regions [4,7,8]. The Orang Kallang, in particular, was one of the tribes that settled on the Kallang River “since time immemorial” in the mangrove swamps of the Kallang Basin in Singapore [8,9]. British Museum curator C.A. Gibson Hill stated in his 1952 paper on the Orang Laut that many moved from the Singapore River to Kallang from 1823 to 1843. Many formed a settlement known as Kampong Melayu Tanjong Rhu around the 1840s due to the increasing maritime traffic in the Singapore River [7,10].

As British rule strengthened in the 19th century, they grew increasingly displeased with the Malay rulers and their accompanying Orang Laut people as they deemed the tribes to be pirates causing detriment to trade activities in the region. British recounts glorified their raid on the Orang Laut as a model of a successful ‘anti-piracy campaign’ in the early 19th century [4]. Ultimately, the loss of livelihood and lack of support from the British led to the assimilation of the Orang Laut into the Malay culture (Malayization), their conversion to Islam, and their ethnic identification as Malay in the early 20th century [7,8]. The culture and identity of the Orang Laut gradually became lost in time, with the only persisting tribe being the Orang Seletar ([11] en passant), now sparsely found in parts of Johor. Both the Orang Kallang and Orang Seletar are considered aboriginal Malays. Mainstream literature sees the use of the word “Proto-Malay”, a term that places the aboriginal Malays as “lesser” or “more primitive” than the modern “Deutero” Malays.

1.2. Historical Significance of the Kallang River

This section mainly references and reviews information retrieved from a recent book by Lee et al. in 2019 [12], endorsed and funded by the Singapore Government. This book was published in conjunction with Singapore’s bicentenary and delved into the historical progression and legacy of the Kallang River.

The name ‘Kallang’ is derived from the Orang Kallang tribe. It is believed by scholars to be a Malay term describing a ‘shipbuilding place’. Due to its strategic location, the Kallang River served as a major port epicenter for business and trading during Singapore’s early history.

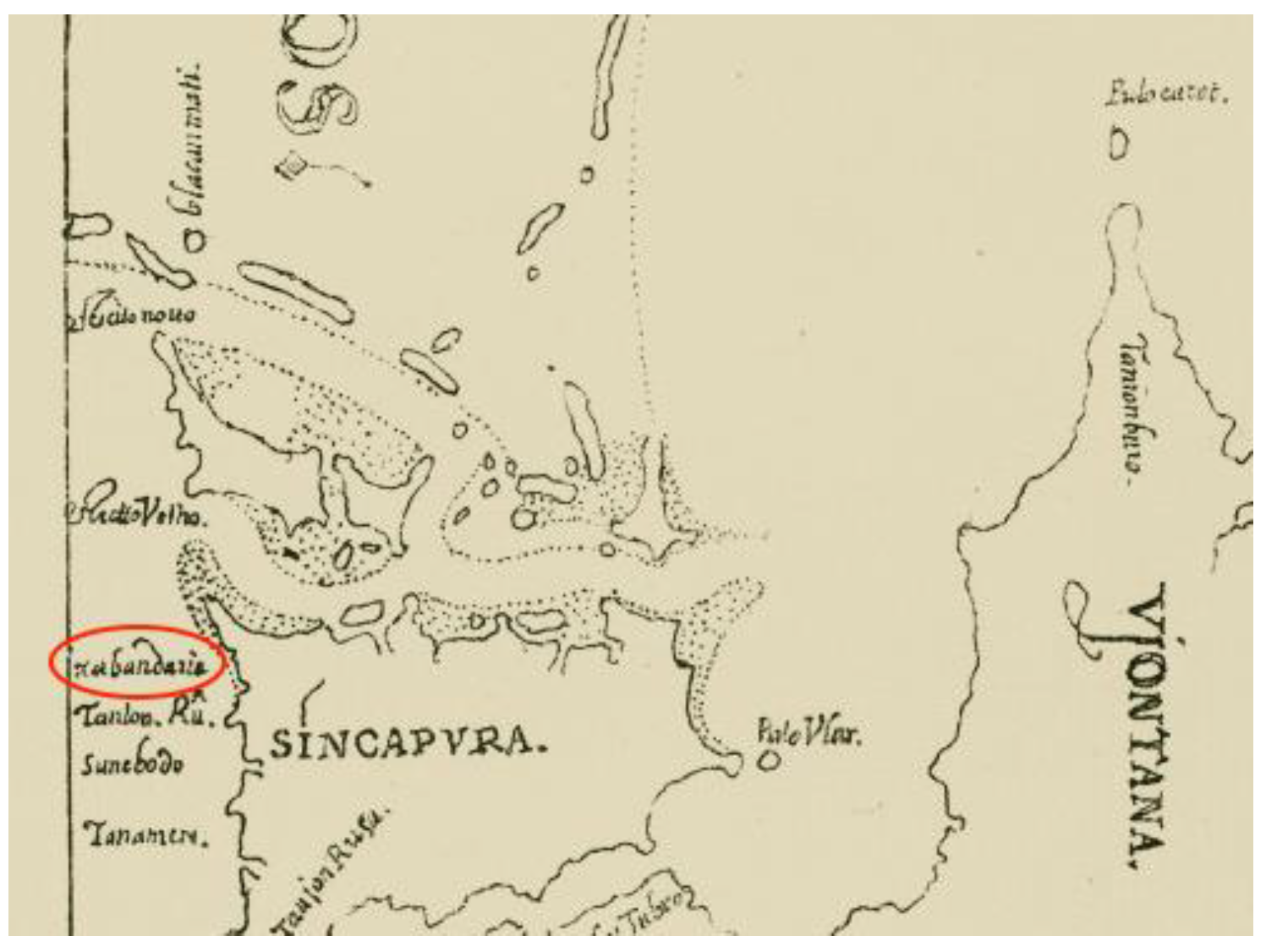

Little is known about the river and its history before the 19th century. However, the prominence of shabandars in Singapore was well-documented, from at least the late 14th century. The name shabandars means “Lord of the Harbor” in Persian. They were prominent foreigners trusted by the local royalty to manage trade and economic activities on their behalf, overseeing matters of the sea. External sources, such as the Portuguese map shown in Figure 1, explicitly reference the Singapore River’s shabandars (recorded as Xabandaria).

Figure 1.

Map of Singapura by Portuguese cartographer Manuel Godinho de Eredias, first drawn in 1604.

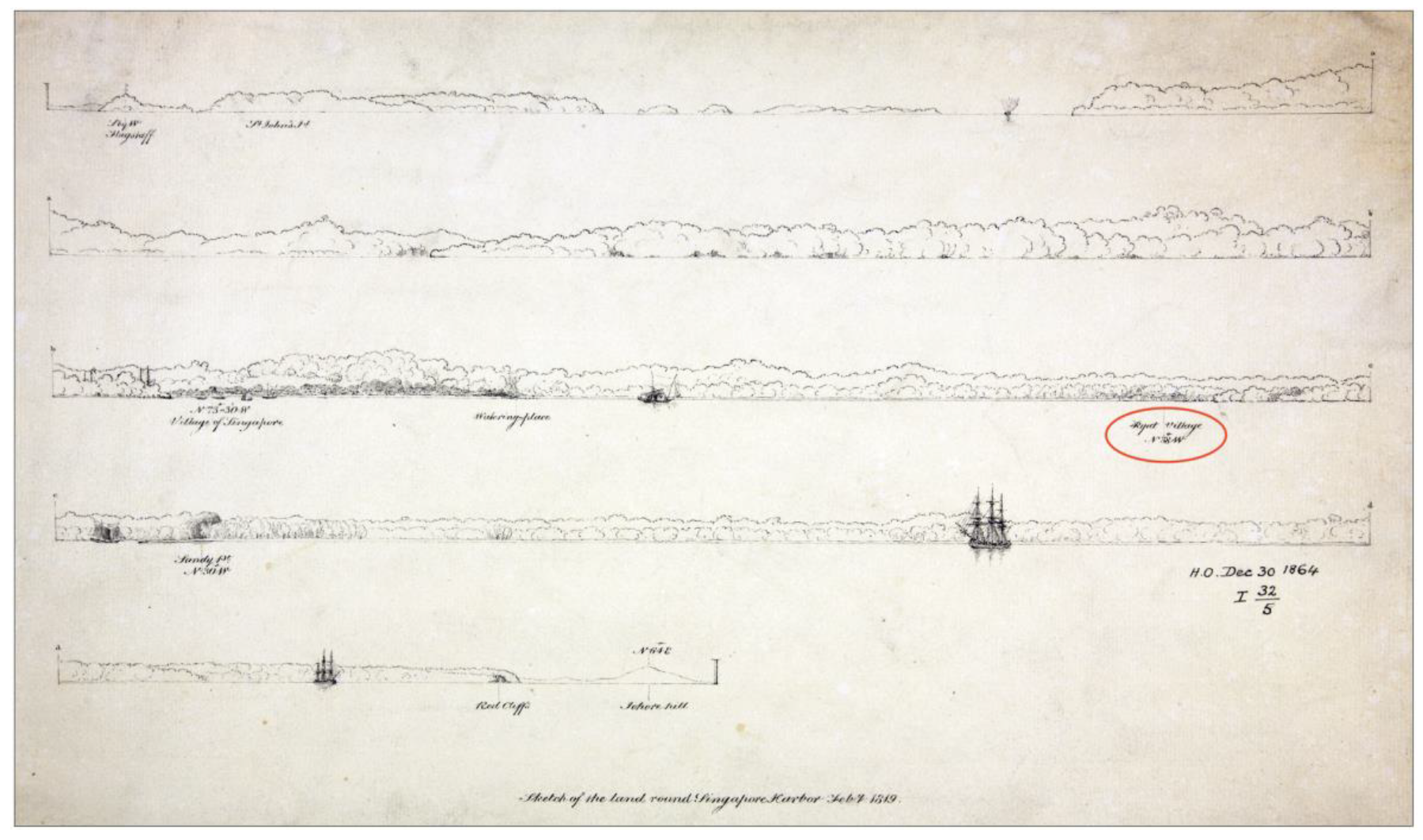

The Kallang River is believed by scholars to have been controlled by a shabandar. Figure 2 shows a British map from 1819 by an unnamed Bombay Marine survey ship member. The reference to a “Ryat Village” near the Kallang estuary is likely linked to a nomad village occupied by the Orang Kallang and the location where the British-appointed royal ruler of Singapore, Sultan Hussein Shah, built his palace.

Figure 2.

Sketch of the land round Singapore Harbor 7 February 1819 [13].

Moreover, historian Professor Kwa Chong Guan of the National University of Singapore also noted that the discovery of 16th-century Chinese blue and white ceramic artifacts further strengthens the theory that the Kallang estuary was a flourishing trading port for most of Singapore’s early history.

Overall, the book’s section on the early history of the river provides the reader with a clear outline of the significance and importance of the river for trade and commerce. Insights from prominent Singapore historians and anthropologists offered unique insights into the river’s pre-colonial history. However, it is essential to highlight that the Singapore Government commissions the book to commemorate Singapore’s rich heritage and history. It is thus to be expected that the book aims to present the river in a glorified light. In actuality, the river port may have been a small part of an extensive trade system in Singapore as Singapore was a thriving maritime hub. Additionally, although the Orang Kallang was described as an essential group of natives to the river, they are portraited as providers of trade materials such as cigarette wrappers (rokok daun) to the locals. Still, there is an apparent lack of description of any external trading activities that would have made their legacy in trade particularly significant or influential.

2. The Origins, Livelihood, and Decline of the Orang Kallang

2.1. Early Origins of the Orang Kallang

According to some living accounts from the descendants of the Orang Kallang tribe, the ancestry of the group can be traced to Daik in the Lingga Archipelago and Bangka Island, Indonesia [8]. Records describe the Orang Kallang as residing in boats on the Kallang River before the arrival of the British in 1819. Unlike most Orang Laut groups, they were described to have little affinity to the open sea, instead preferring to reside at the mouth of the Kallang river, relying on fishing and fresh produce from the surrounding forests for survival [12].

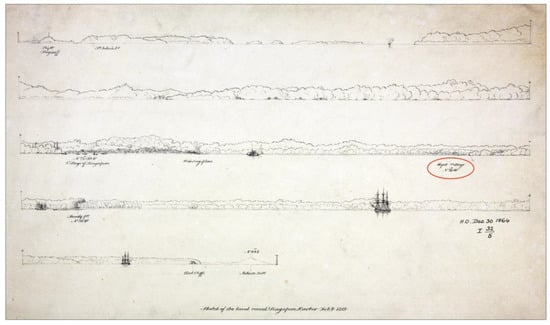

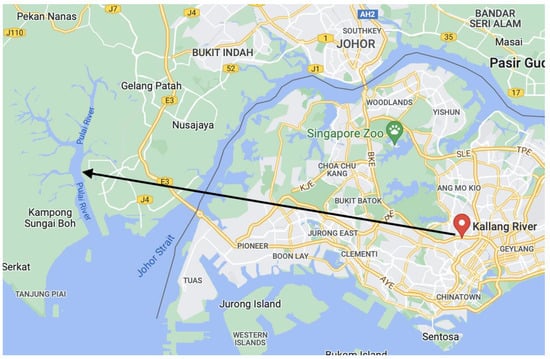

Upon the British eradication attempt of the Orang Laut after 1819, the Orang Kallang were also impacted as the British designated the Kallang region as a supplementary trading center. As a result, the Temenggong (Temenggong is a traditional title for a Malay nobleman ranking third after the ruler of the old Johor empire) resettled most of the Orang Kallang to the Pulai River in Johor [14]. However, according to accounts by the purported descendants of the Orang Kallang, a small population remained and thrived on the Kallang River up to the 1930s [8]. Figure 3 and Figure 4 show geographical references of the direction of migration by the resettlement.

Figure 3.

1898 Cuylenburg/Stanford Map of Malaya Peninsula: Malaysia, Singapore, Siam.

Figure 4.

Present Map of Singapore and Johor, Google Maps.

2.2. Livelihood

Some living elderly Singaporeans have spoken out about their memories of living on the Kallang River in the early years of their lives, as well as stories from their grandparents about their Orang Kallang heritage [7,8,15]. This likely indicates that some members of the Orang Kallang tribe did not move to River Pulai and instead remained in the area even after the British arrival.

The descendants outlined the existence of five villages: Kampung Kallang Pasir, Kallang Pokok, Kallang Laut, Kallang Batin, and Kallang Rokok (the biggest), with a combined population totaling around 5000 [8]. The villages were likely to have been under the control and guidance of a Temenggong in the 19th century, with each village allocated specific occupational roles. A chief serving the Temenggong (known as a Jenang) would be tasked to ensure the smooth execution of the labor [8]. The tribe initially focused on trading, employing larger vessels known as nadih to navigate the seas and travel to nearby regions. Subsequently, a shift in focus to fishing popularized the sampan, a smaller and more efficient vessel [8]. Some tasks conducted by the Orang Kallang include: providing water transportation and ferry services; making cigarette wrappers from nipah leaves; and collecting mangrove wood (bakau, Rhizophora sp.) to be sold to the Malays and Chinese for fuel production [8]. The Orang Kallang continued to function as a community on the Kallang River despite the disintegration of the Malay nobility, continuing into the turn of the 20th century.

2.3. Language

Unfortunately, little is known about the language spoken by the Orang Kallang, as there have been no documented findings. Moreover, modern descendants of the Orang Kallang no longer speak their original language, and the knowledge is presumed to be lost—most of them now speak modern Malay.

Some brief descriptions and documented words were retrieved from field studies such as Skeat & Ridley [14] from ‘The Cambridge University Expedition to the North-Eastern Malay States, and to Upper Perak, 1899–1900′ [16]. In 1900, they recorded unique words spoken by the men of the Orang Kallang (broadly described by the researchers as Orang Laut) living in Kampong Rokok at the turn of the 19th century, who ascertained that their ancestors were from the Riau-Lingga islands [14] (p. 248). Phonetically, it was noted that the men often pronounced the /s/ phoneme as a /z/. eg. Nazi for Nasi, /r/ pronounced similar to /h/, e.g., Parang for Pahang. /k/ is pronounced similar to /kh/, e.g., Khain for Kain, indicating the use of aspirated stops in the language. The researchers also found the use of unique vocabulary by the men that were not in the Malay language. Words such as koyok ‘dog’, sika ‘here’, diko ‘you’, kiyan ‘come here’, kiyun ‘go away’, kiyoh ‘far off’, show similarity to words in the language of other Orang Laut groups, such as Orang Barok, Orang Gallang ‘koyok’, ‘sikə’, ‘dikau’. The word ‘diko’ is still used by Malays who trace their ancestral origins to Riau [17] (timestamp 26:13). Moreover, sika and kiyan are also present in the Seletar variety.

The fieldwork provides strong evidence that Orang Kallang likely had ancestral ties to the Orang Laut of Riau-Lingga, and it is conceivable that their language could have been related. The fieldwork, gathered at the turn of the 20th century, provides a rare glimpse into undocumented periods of the Orang Kallang people and their language. This is a period where the language is expected to be in its early forms, before the integration of th community into the larger Malay community and subsequent loss of language features. However, as the authors stated, the examples and recorded data should not be taken as linguistically accurate as there was a lack of repeated checks. The expedition notes stated that the fieldworkers only stayed in Singapore for eight days with only two short visits to the Orang Laut settlements [16] (p. 124). Another point is that locals may have expressed the words differently because they were interacting with non-local Europeans. On top of the limitations expressed by the authors, another limitation would be that the European fieldworkers may not have been able to accurately capture linguistic nuance in the native Orang Kallang language without the assistance of a native fieldworker. From the article, it appears that the fieldworkers gathered a small number of fewer than 30 words. Although the field study was conducted before the introduction of the Swadesh list, it is clear that the data gathered was insufficient for a comprehensive linguistic analysis.

In a master’s thesis by Zhi Xuan Tan studying the language of the Orang Seletar, she states that the Orang Seletar language is also considered an Orang Laut/Sea Tribe variety [18] (p. 37–39). For the purposes of this paper, Tan has kindly provided her input on the links between the Orang Kallang and Orang Seletar and their language varieties. She highlights that the Pulai River, where some families of the Orang Kallang relocated, was and still is an important resource site of the Orang Seletar. The two populations may have been in contact and have intermarried. She cites sources such as Skeat & Blagden [19], claiming that the Orang Seletar and the Orang Kallang are “branches of one tribe”. The variety spoken by the descendants of the Orang Kallang is said to be similar to the speech of the Orang Seletar (oral recount by Malay resident, 1985) [20]. The characteristic features of the Orang Laut varieties can be found in [21] (p. 297).

Tan concludes that the Orang Kallang and Orang Seletar are both Orang Laut/Sea Tribe Malay varieties and most probably shared features common to various Orang Laut/Sea Tribes of Riau (e.g., numerous glottal stops closing, kian/kiun/kiyoh triplet, see [21]). Overall, she believes that archival accounts point to them being very similar, but other than the words described above, concrete data on the topic is severely lacking.

Based on sparse linguistic information available, the Orang Kallang language is hypothesized to be significantly linked to Orang Laut of Riau-Lingga and even the Orang Seletar, most likely descending from the same ancestral language or proto-language family before the Orang Laut populations spread into different regions. Unfortunately, the lack of documentation, loss of native speakers, and deterioration or integration of linguistics characteristics into other languages, such as Malay, poses a significant challenge in providing insights into the Orang Kallang language and its ancestral language.

2.4. Eventual Decline

For the Orang Kallang families that moved to Johor in the early 19th century, a smallpox epidemic around 1847–1848 occurred soon after the move to Pulai River. The epidemic proved devastating, as the 100 Orang Kallang families dwindled to only eight [14]. Another group of sea-farers, the Bugis, a South Sulawesi race that migrated to Singapore in the 17th century, initially engaged in farming activities. Still, it became increasingly active in maritime enterprise from the 18th century [22]. They initially co-habited with the Orang Kallang but were less prominent in the area than the Orang Kallang. They mainly reside in Kampong Bugis, located along the Rochor and Kallang Rivers [12]. With the arrival of the British, the Bugis overshadowed the Orang Kallang. The Bugis were traders known to be interested in political matters and technical advancement, compared to the nomadic tendencies of the Orang Kallang. The British greatly favored the Bugis and gradually built a mutually beneficial relationship. The Bugis began maintaining trade along the Kallang River and soon took control of the Kallang Basin.

On the other hand, the families that stayed behind on the Kallang River also faced issues because the modernization of Singapore would soon affect their residence on the river. With the plans for the construction of the now-defunct Kallang Civil Airport, Malay-rights community advocate Eunos Abdullah, the namesake of the present-day Singaporean district of ‘Eunos’, along with philanthropist Haji Ambo Sooloh, petitioned the government to rehouse the affected Malay-dominated population, including the Orang Kallang [23] (p. 7). As a result, the government rehoused the remaining Orang Kallang into Kampung Melayu Jalan Eunos or Jalan Eunos Malay Settlement in 1932 [8], while others moved to Kampong Melayu Tanjong Rhu.

This switch to land-dwelling led to the erosion of the cultural identity of the Orang Kallang, who prided themselves on their intense connection to the sea as a sacred part of their identity and their affiliation to sea-faring and maritime activities [7,8]. With their livelihood and core identity removed, many Orang Kallang people integrated into the general Malay community [8]. The Japanese air attacks on Kallang drove out the remaining settlers in Kampong Melayu Tanjong Rhu in December 1942 during World War 2 [10]. Some descendants to this day, however, take pride in their heritage and links to the Orang Kallang populations as ‘Sea People’, choosing to work and engage in maritime and sea activities [7].

3. Orang Kallang’s Move to Johor: The Impact of Smallpox on the Aboriginal Communities of the Region

3.1. History and Spread of Smallpox within Asia and Its Impact on Southeast Asia

According to the American Centers for Disease Control and Prevention [24], the origin of smallpox is unknown. Still, that smallpox could have been present as far back as the Egyptian Empire in the 3rd century BCE. Disease transmission occurs from human to human via direct and relatively prolonged face-to-face contact during its acute stage. As the ancient world became increasingly interconnected, the disease reached a level of endemicity in densely populated areas such as India and China [24,25]. The disease was introduced to Europe via contact with other communities between the 15th and 17th centuries, with frequent epidemics appearing during the Middle Ages [25]. The crusades in the 11th century CE brought the disease into Europe as they traveled to and from the Middle East up to the 13th century. European colonizers caused a further spread of the disease from the 15th century CE, initially from expeditions and importation of enslaved Africans into the Caribbean, Central, and South America, followed by a spread to North America in the 17th century [24].

In Southeast Asia, trade with China and India led to the spread of the disease long before the arrival of the European colonizers, although the exact time period is uncertain [26]. Additionally, as European colonizers from Britain, France, and Holland took over Southeast Asian lands for its prosperous spice trade starting from the 16th and 17th centuries, the disease could have been further introduced into the communities by the colonizers.

In Fenner’s 1987 [26] paper ‘Smallpox in Southeast Asia’, he states that aboriginal populations’ lack of prior exposure to the disease and their insufficient knowledge of modern medicine proved to be a deadly combination as the virus spread rapidly through the aboriginal communities, resulting in a high fatality rate. The fatality rate of unvaccinated individuals in Asia was devastating, estimated at 25%, with most death occurring in infants, elderly individuals, and pregnant women. Regions such as Siam and Indochina were rife with the disease due to frequent trade with India and China, leading to numerous documented epidemics between the 16th and 18th centuries. According to Dutch and Portuguese travelers in the 16th century, the populations in the Malay Archipelago and the Philippines were sparse. They consisted of small, localized tribes, which meant that individual communities and tribes were too small to cause endemicity of the disease in most regions, except Bali and Java, which had denser populations. In the northern regions of Southeast Asia, the disease was documented to be present in Penang in 1805, while smallpox in Singapore appeared to have only occurred soon after British colonization in 1819, with epidemics occurring throughout the early 19th century and early 20th century.

3.2. Vaccination Failures in Southeast Asia

In 1796, English doctor Edward Jenner successfully proved the effectiveness of a method called ‘variolation’ to help protect individuals from diseases such as smallpox, leading to a massive vaccination effort in Europe that was adopted at a remarkable speed [27]. However, colonies such as Asia faced multiple issues with vaccination efforts.

Although vaccines reached the area in the early 19th century, they were initially reserved for expatriates or prominent and wealthy residents [26]. Another recurring issue was a constant supply shortage or shipment hiccups. A prominent study by the pioneering physician and medical administrator Professor Lee Yong Kiat [27,28] specifically investigates smallpox and vaccination in early Singapore between 1819 and 1872. However, this section will focus mainly on part II [28], focusing on the years between 1830 and 1849. He outlines the impact of the disease on the Singapore community and the early failed attempts by the British to vaccinate the population. The vaccination was first approved and sent to Penang around 1805 to be shipped from Calcutta. However, issues soon arose as complaints of a lack of supply, hot weather affecting the freshness of the vaccines, as well as a poor uptake of the vaccine by the local population. In 1829, issues with expenses led to the decision by the British to abolish the Vaccine Department in Penang and Singapore. Vaccination efforts would prove futile in controlling the endemicity of smallpox for at least a century, with smallpox continuing to be a problem up to the 1950s in Singapore and the nearby Malacca region.

With an epidemic breaking out in 1849, the Singapore Free Press wrote in March of that year about the devastating fatality rates:

“We are sorry to hear that Smallpox at present prevails to some extent amongst the natives, and that about 250 deaths have taken place from this disease principally amongst children, the average daily mortality from this source being about 7or 8.” [28](p. 204).

The editor of The Straits Times (The Straits Times is a longstanding Singapore daily broadsheet newspaper written in English. It was established on 15 July 1845 by its original name, The Straits Times and Singapore Journal of Commerce) in June 1849, noted the severity of the situation, not only in Singapore but in the region of Malacca and nearby areas:

“Smallpox is again raging with renewed virulence in Singapore, principally amongst the native community. Indeed the disease seems to be extending all over the Peninsula and adjacent islands…” [28](p. 204).

Most notably, the years of this epidemic coincide closely with the years that struck the Orang Kallang people in Johor’s Pulai River, which is approximately 46.8 km/29 miles from Singapore. Essentially, it is conceivable that the wave of epidemics would have been particularly devastating for aboriginal tribes such as the Orang Kallang. As the Pulai River is located within a dense mangrove forest housing only a few rural villages far from the main cities and medical centers, the Orang Kallang on the Pulai River would not have had ready access to smallpox vaccination or treatment. This could have been the main reason for their substantial decline in the disease. Some other factors that could have worsened the disease’s spread among the tribe include their nomad lifestyles and preference for simple technology and living conditions, as well as their tendency to live in large groups on the river, with multiple families intermingling. The Orang Kallang would thus have also been unlikely to be at the forefront of vaccination efforts compared to denser, modernized communities in the region closer to the British vaccine providers and doctors, which even then had troubled vaccination efforts themselves as well.

4. Conclusions

In summary, this article aims to shed light on the largely forgotten history of the Orang Kallang tribe, a group of Aboriginal Singaporeans that played a crucial role in the trade and maritime activities on the river in most of Singapore’s pre-1819 history. The article delves into the links between the more prominently studied Orang Laut tribe and how the Orang Kallang came to adapt to the mangrove swamps of the Kallang River. It is hypothesized that they have had a unique language linked to the Orang Seletar and other Orang Laut tribes’ language varieties. The article also studies the impact of British colonization on the tribe, as the British’s disdain for the Orang Kallang led to the tribe’s subsequent split. Some families moved to the River Pulai in Johor, while others remained in the Kallang River as the tribe faced lessened political and trading power. Lastly, the eventual demise of most of the Pulai River members from smallpox, as well as the cultural decline and relocation of remaining Kallang River families, are outlined in the final sections. Various sources on the Orang Kallang are scattered and not always fully comprehensive. Singapore’s pre-colonial history and peoples have generally been studied marginally, with many sources being lost over time or not being thoroughly analyzed. Overall, this article aims to provide a clearer picture of this largely forgotten group of native inhabitants and a glimpse into Singapore’s pre-colonial history.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, F.P.C. and B.M.Q.O.; Writing—original draft, B.M.Q.O.; Writing—review & editing, F.P.C. and B.M.Q.O. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Zhi Xuan Tan for providing valuable insights on the topic.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Andaya, L.Y. The Orang Laut and the Malayu. In Leaves of the Same Tree; Trade and Ethnicity in the Straits of Melaka; University of Hawai’i Press: Honolulu, HI, USA, 2008; pp. 173–201. [Google Scholar]

- Orang Kallang. Berita Minggu; 1985. Available online: https://eresources.nlb.gov.sg/newspapers/Digitised/Article/beritaharian19850113-1.2.14.2?ST=1&AT=search&k=%22orang%20seletar%22&SortBy=Oldest (accessed on 4 July 2022).

- Ferrand, G. Relations de Voyages et Textes Géographiques Arabes, Persans et Turks Relatifs a l’Extrême-Orient du VIIIe au XVIIIe Siècles; Ernest Leroux: Paris, France, 1913. [Google Scholar]

- Barnard, T.P. Celates, Rayat-Laut, Pirates: The Orang Laut and Their Decline in History. J. Malays. Branch R. Asiat. Soc. 2007, 80, 33–49. [Google Scholar]

- Chou, C. The Orang Suku Laut of Riau, Indonesia: The Inalienable Gift of Territory; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Linehan, W. The Kings of 14th Century Singapore. J. Malays. Branch R. Asiat. Soc. 1969, 42, 53–62. [Google Scholar]

- Siti Nur Aisha, O. The Orang Laut and the Tide of Time; Nanyang Technological University: Singapore, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Ali, M. Singapore’s Orang Seletar, Orang Kallang, and Orang Selat: The Last Settlements. In Tribal Communities in the Malay World: Historical, Cultural and Social Perspectives; Benjamin, G., Chou, C., Eds.; ISEAS Publishing: Singapore, 2002; pp. 273–292. [Google Scholar]

- Sopher, D.E. The Sea Nomads; A Study Based on the Literature of the Maritime Boat People of Southeast Asia; National Museum: Singapore, 1977. [Google Scholar]

- Gibson-Hill, C.A. The Orang Laut of the Singapore River and the Sampan Panjang. J. Malay. Branch R. Asiat. Soc. 1952, 25, 161–174. [Google Scholar]

- De Bellina, B.; Blench, R.; Galipaud, J. Sea Nomads of Southeast Asia: From the Past to the Present; NUS Press, National University of Singapore: Singapore, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, P.; Lee, C.; Kor, J.; Pang, X.Q.; Silvam, P. Our Home by the Kallang River: Past, Present and Future; World Scientific Publishing Company Pte. Limited/Kolam Ayer Citizens’ Consultative Committee: Singapore, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Langdon, M.; Guan, K.C. Notes on ‘Sketch of the Land round Singapore Harbour, 7 February 1819’. J. Malays. Branch R. Asiat. Soc. 2010, 83, 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Skeat, W.K.; Ridley, H.N. The Orang Laut of Singapore. J. Malays. Branch R. Asiat. Soc. 1969, 42, 114–116. [Google Scholar]

- Paulo, D.A. In Search of the Real Singapore Stories, beyond Raffles. Available online: https://www.channelnewsasia.com/cnainsider/search-real-singapore-story-beyond-stamford-raffles-bicentennial-897671 (accessed on 30 June 2022).

- Gibson-Hill, C.A.; Skeat, W.W.; Laidlaw, F.F. The Cambridge University Expedition to the North-Eastern Malay States, and to Upper Perak, 1899–1900. J. Malay. Branch R. Asiat. Soc. 1953, 26, 1–174. [Google Scholar]

- Orang Laut yang HILANG (The Lost Orang Laut of Singapore)|Hilang EP1. [Video]. Youtube. 2019. Available online: https://youtu.be/x50ryn_QRCs (accessed on 4 July 2022).

- Tan, Z.X. Some Aspects of the Language of the Orang Seletar; Nanyang Technological University: Singapore, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Skeat, W.W.; Blagden, C.O. Pagan Races Of The Malay Peninsula Vol.1; The Macmillan Company: New York, NY, USA, 1906. [Google Scholar]

- Osman, A. Communities of Singapore (Part 3) Communities of Singapore (Part 3): Interview with AWANG bin Osman, Oral History Interview, Oral History Centre; National Archives of Singapore: Singapore, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Anderbeck, K. The Malayic-speaking; Orang Laut Dialects and directions for research. Wacana J. Humanit. Indones. 2012, 14, 265–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pelras, C. The Bugis; Blackwell Publishers Ltd.: Oxford, UK, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Kahn, J.S. Other Malays: Nationalism and Cosmopolitanism in the Modern Malay World; NUS Press (National University of Singapore): Singapore, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- The Spread and Eradication of Smallpox. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/smallpox/pdfs/smallpox-timeline.pdf (accessed on 30 June 2022).

- Riedel, S. Edward Jenner and the history of smallpox and vaccination. Bayl. Univ. Med. Cent. Proc. 2005, 18, 21–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fenner, F. Smallpox in Southeast Asia. Crossroads: An Interdisciplinary. J. Southeast Asian Stud. 1987, 3, 34–48. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, Y.K. Smallpox Vaccination in Early Singapore (Part I) (1819–1829). Singap. Med. J. 1973, 14, 525–531. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, Y.K. Smallpox Vaccination in Early Singapore (Part II) (1830–1849). Singap. Med. J. 1976, 17, 202–206. [Google Scholar]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).