Application of Spirulina platensis and Chlorella vulgaris for Improved Growth and Bioactive Compound Accumulation in Achillea fragrantissima In Vitro

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Preparation of S. platensis and C. vulgaris Aqueous Extracts

2.2. Analysis of S. platensis and C. vulgaris Powder Compositions

2.3. Establishment of In Vitro A. fragrantissima

2.4. In Vitro Multiplication (Shoot Tip Explants) and Elicitor Treatments

2.5. Photosynthetic Pigment Analysis

2.6. Identification of Phytochemical Compounds by GC–MS

2.7. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Chemical and Phytochemical Composition of S. platensis and C. vulgaris

3.2. Effects of Spirulina platensis, Chlorella vulgaris, and Their Combination on Shoot Induction of A. fragrantissima

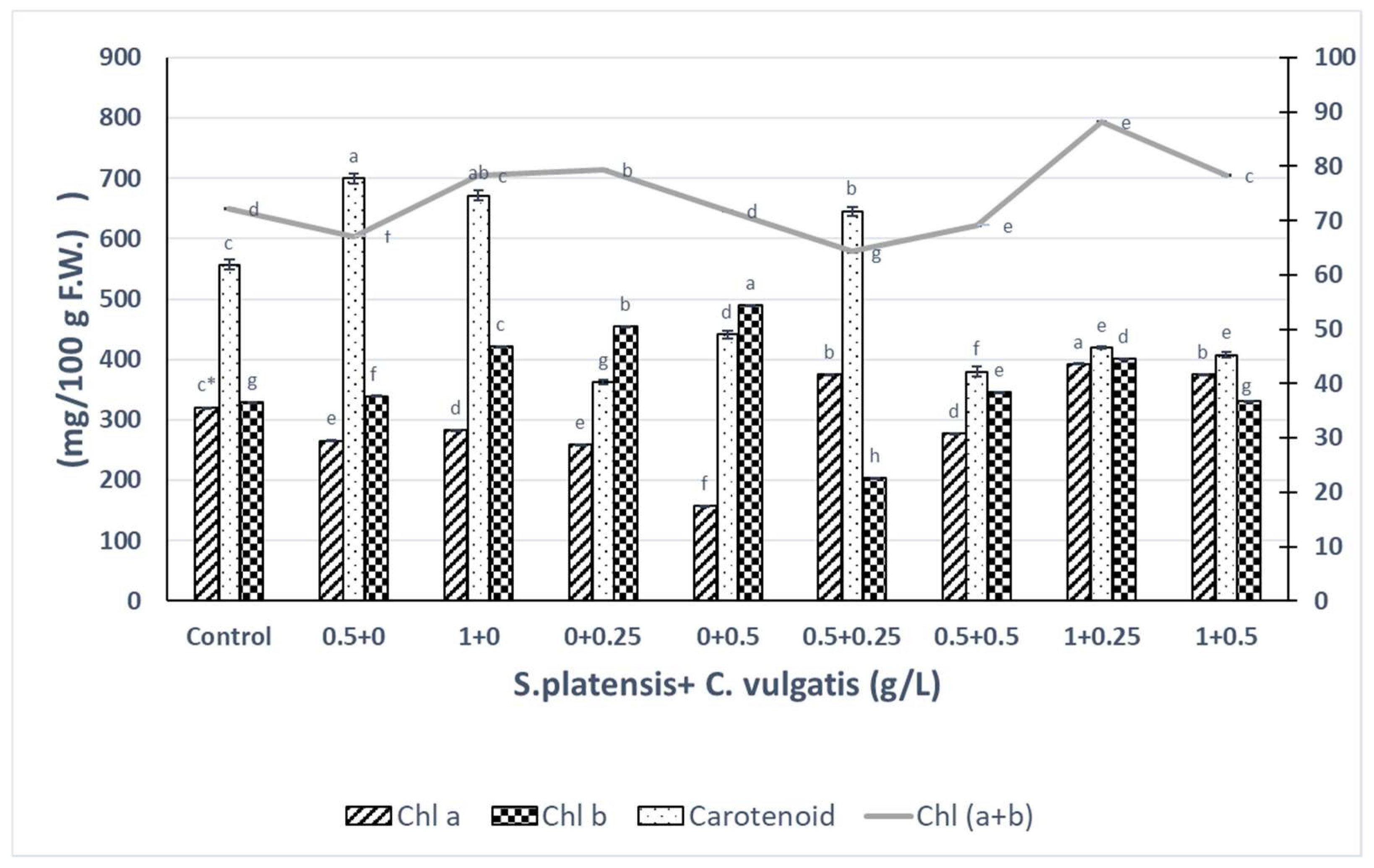

3.3. The Effects of S. platensis and C. vulgaris Extracts and Their Combination on Photosynthetic Pigments of A. fragrantissima In Vitro Plantlets

3.4. The Effects of S. platensis and C. vulgaris Extracts on the Essential Oil Composition of A. fragrantissima

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Alasmari, A. Achillea fragrantissima (Forssk.) Sch.Bip instigates the ROS/FADD/c-PARP expression that triggers apoptosis in breast cancer cell (MCF-7). PLoS ONE 2024, 19, e0304072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rolnik, A.; Olas, B. The plants of the asteraceae family as agents in the protection of human health. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 3009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tawfik, N.F.; El-Sayed, N.; Mahgoub, S.; Khazaal, M.T.; Moharram, F.A. Chemical analysis, antibacterial and anti-inflammatory effect of Achillea fragrantissima essential oil growing wild in Egypt. BMC Complement. Med Ther. 2024, 24, 385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patocka, J.; Navratilova, Z. Achillea fragrantissima: Pharmacology Review. Clin. Oncol. 2019, 4, 1601. [Google Scholar]

- El-Ashmawy, I.M.; Al-Wabel, N.A.; Bayad, A.E. Achillea fragrantissima, rich in flavonoids and tannins, potentiates the activity of diminazine aceturate against Trypanosoma evansi in rats. Asian Pac. J. Trop. Med. 2016, 9, 228–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goda, M.S.; Ahmed, S.A.; Sherif FEl Khattab, S.; Hassanean, H.A.; Alnefaie, R.; Althumairy, D.; Abo-elmatty, D.M.; Ibrahim, A.K. In Vitro Micropropagation of Endangered Achillea fragrantissima Forssk. Combined with Enhancement of Its Antihyperglycemic Activity. Agronomy 2023, 13, 278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdel-Rahman, R.F.; Alqasoumi, S.I.; El-Desoky, A.H.; Soliman, G.A.; Paré, P.W.; Hegazy, M.E.F. Evaluation of the anti-inflammatory, analgesic and anti-ulcerogenic potentials of Achillea fragrantissima (Forssk.). S. Afr. J. Bot. 2015, 98, 122–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diab, M.K.; Abu-Elsaoud, A.M.; Salama, M.G.; Ghareeb, E.M. Phytochemical treasure troves—Insights into bioactivities, phytochemistry, and uses of Artemisia species. In Phytochemistry Reviews; Springer Science and Business Media B.V.: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Abu-Irmaileh, B.; Al-Hroub, H.M.; Rasras, M.H.; Hudaib, M.; Semreen, M.H.; Bustanji, Y. Phytochemical composition and antiviral properties of A. fragrantissima methanolic extract on H1N1 virus. Pharmacia 2025, 72, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumari, S.; Dalania, K.; Magotra, S.; Singh, A.K.; Negi, N.P. Sustainable energy solutions: The role of biotechnology and algal biofuels in environmental preservation. Discov. Biotechnol. 2025, 2, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heo, Y.; Kim, M.Y.; Cho, J.Y. Chlorella vulgaris, a representative edible algae as integrative and alternative medicine. Integr. Med. Res. 2025, 15, 101228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babich, O.; Ivanova, S.; Michaud, P.; Budenkova, E.; Kashirskikh, E.; Anokhova, V.; Sukhikh, S. Synthesis of polysaccharides by microalgae Chlorella sp. Bioresour. Technol. 2024, 406, 131043. [Google Scholar]

- Del Prete, F.; Esposito, T.; Pane, C.; Manganiello, G.; Pepe, G.; Salviati, E.; Campiglia, P.; Mencherini, T.; Sansone, F.; Aquino, R.P. Extract from Chlorella vulgaris: Production, characterization, and effects on the germination, growth and metabolite profile of Eruca sativa microgreens. Ind. Crops. Prod. 2025, 233, 121490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uzlaşır, T.; Selli, S.; Kelebek, H. Spirulina platensis and Phaeodactylum tricornutum as sustainable sources of bioactive compounds: Health implications and applications in the food industry. Future Postharvest Food 2024, 1, 34–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dineshkumar, R.; Kumaravel, R.; Gopalsamy, J.; Sikder, M.N.A.; Sampathkumar, P. Microalgae as Bio-fertilizers for Rice Growth and Seed Yield Productivity. Waste Biomass Valorization 2018, 9, 793–800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonçalves, J.; Freitas, J.; Fernandes, I.; Silva, P. Microalgae as Biofertilizers: A Sustainable Way to Improve Soil Fertility and Plant Growth. Sustainability 2023, 15, 12413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abreu, A.P.; Martins, R.; Nunes, J. Emerging Applications of Chlorella sp. and Spirulina (Arthrospira) sp. Bioengineering 2023, 10, 955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Balo, Y. Elimination of Contamination in Plant Tissue Culture Laboratory. Acta Bot. Plantae 2023, 2, 22–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wijerathna-Yapa, A.; Hiti-Bandaralage, J.; Pathirana, R. Harnessing metabolites from plant cell tissue and organ culture for sustainable biotechnology. Plant Cell Tissue Organ Cult. 2025, 162, 55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aldaif, M.; Albastawisi, E.M. Plant Tissue Culture-Derived Secondary Metabolites: A Promising and Sustainable Alternative to Synthetic Pesticides. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/393011781 (accessed on 30 November 2025).

- Hammoud Abdulameer, S.; AL-Nasrawi, W.S.; ALjarah, M.H.; AL-Ibrahemi, N. The effect of Chlorella vulgaris and Spirulina platensis on enhancing the active compounds in basil (Ocimum basilicum L.) seeds and their role in supporting human health. J. Health Med. Sci. 2025, 3, 56–65. [Google Scholar]

- Jamshidi-Kia, F.; Saeidi, K.; Lorigooini, Z.; Samani, B.H. Efficacy of foliar application of Chlorella vulgaris extract on chemical composition and biological activities of the essential oil of spearmint (Mentha spicata L.). Heliyon 2024, 10, e40531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gharib, F.A.E.L.; Ahmed, E.Z. Spirulina platensis improves growth, oil content, and antioxidant activitiy of rosemary plant under cadmium and lead stress. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 8008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al Dayel, M.F.; El Sherif, F. Spirulina platensis Foliar Spraying Curcuma longa Has Improved Growth, Yield, and Curcuminoid Biosynthesis Gene Expression, as Well as Curcuminoid Accumulation. Horticulturae 2022, 8, 469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar Jangid, A. Potential of Algal Based Biofertilizer and their use in Sustainable Agriculture. In Emerging Trends in Sustainable Agriculture; Vital Biotech Publication: Kota, India, 2024; Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/385438200 (accessed on 30 November 2025).

- Rupawalla, Z.; Robinson, N.; Schmidt, S.; Li, S.; Carruthers, S.; Buisset, E.; Roles, J.; Hankamer, B.; Wolf, J. Algae biofertilisers promote sustainable food production and a circular nutrient economy—An integrated empirical-modelling study. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 796, 148913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasnain, A.; Naqvi, S.A.H.; Ayesha, S.I.; Khalid, F.; Ellahi, M.; Iqbal, S.; Hassan, M.Z.; Abbas, A.; Adamski, R.; Markowska, D.; et al. Plants in vitro propagation with its applications in food, pharmaceuticals and cosmetic industries; current scenario and future approaches. Front. Plant Sci. 2022, 13, 1009395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chandran, H.; Meena, M.; Barupal, T.; Sharma, K. Plant tissue culture as a perpetual source for production of industrially important bioactive compounds. Biotechnol. Rep. 2020, 26, e00450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amin, G.H.; Al-Gendy, A.A.; Yassin, M.E.A.; Abdel-Motteleb, A. Effect of Spirulina Platensis extract on growth, phenolic compounds and antioxidant activities of Sisymbrium Irio callus and cell suspension cultures. Aust. J. Basic Appl. Sci. 2009, 3, 2097–2110. [Google Scholar]

- Cottenie, A.; Camerlynck, R.; Verloo, M.; Dhaese, A. Fractionation and Determination of Trace Elements in Plants, Soils and Sediments. In Proceedings of the 27th International Congress of Pure and Applied Chemistry, Helsinki, Finland, 27–31 August 1979; Volume 52, pp. 45–53. [Google Scholar]

- Murphy, J.; Riley, J.P. A Modified single-solution method for the determination of phosphorus in natural water. Anal Chim. Acta. 1962, 27, 31–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazumdar, B.; Majumder, K. Methods of Physiochemical Analysis of Fruits; Daya Publishing House: Delhi, India, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Shindy, W.W.; Smith, O.E. Identification of Plant Hormones from Cotton Ovules. Plant Physiol. 1975, 55, 550–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qian, H.; Sheng, M. Simultaneous determination of fat-soluble vitamins A, D and E and pro-vitamin D2 in animal feeds by one-step extraction and high-performance liquid chromatography analysis. J. Chromatogr. A 1998, 825, 127–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moore, S.; Stein, W.H. A modified ninhydrin reagent for the photometric determination of amino acids and related compounds. J. Biol. Chem. 1954, 211, 907–913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DuBois Michel Gilles, K.A.; Hamilton, J.K.; Rebers, P.A.; Smith, F. Colorimetric Method for Determination of Sugars and Related Substances. Anal. Chem. 1956, 28, 350–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- A.O.A.C. Official Methods of Analysis of the AOAC, 14th ed.; Helrich, K.C., Ed.; Association of Official Analytical Chemists: Washington, DC, USA, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, K.B.; Choi, J.; Ahn, S.K.; Na, J.K.; Shrestha, K.K.; Nguon, S.; Park, S.U.; Choi, S.; Kim, J.K. Quantification of Arbutin in Plant Extracts by Stable Isotope Dilution Gas Chromatography–Mass Spectrometry. Chromatographia 2018, 81, 533–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shapiro, S.S.; Wilk, M.B. An Analysis of Variance Test for Normality (Complete Samples). Biometrika 1965, 52, 591–611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levene, H. Robust tests for equality of variances. In Contributions to Probability and Statistics: Essays in Honor of Harold Hotelling; Olkin, I., Ed.; Stanford University Press: Stanford, CA, USA, 1960; Volume 2, pp. 278–292. [Google Scholar]

- Chmiel, D.; Wallan, S.; Haberland, M. tukey_hsd: An Accurate Implementation of the Tukey Honestly Significant Difference Test in Python. J. Open Source Softw. 2022, 7, 4383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podgórska-Kryszczuk, I. Spirulina—An Invaluable Source of Macro- and Micronutrients with Broad Biological Activity and Application Potential. Molecules 2024, 29, 5387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spínola, M.P.; Mendes, A.R.; Prates, J.A.M. Chemical Composition, Bioactivities, and Applications of Spirulina (Limnospira platensis) in Food, Feed, and Medicine. Foods 2024, 13, 3656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, R.F.M.; El-Anany, A.M.; Almujaydil, M.S.; Alhomaid, R.M.; Alharbi, H.F.; Algheshairy, R.M.; Alzunaidy, N.A.; Alqaraawi, S.S. Impact of Chlorella vulgaris powder on the nutritional content and preference of Khalas date spread. Front. Nutr. 2025, 12, 1617754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fiorentino, S.; Bellani, L.; Santin, M.; Castagna, A.; Echeverria, M.C.; Giorgetti, L. Effects of Microalgae as Biostimulants on Plant Growth, Content of Antioxidant Molecules and Total Antioxidant Capacity in Chenopodium quinoa Exposed to Salt Stress. Plants 2025, 14, 781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Narendra, K.; Lakshmi, K.S.; Khan, Z.; Latha, G.S.; Latha, M.M.; Ragalatha, R.; Xavier, J.; Kumar, N.V.; Mallikarjuna, K. Algal Extracts and Their Importance in Promoting Plant Growth. Afr. J. Bio. Sc. 2024, 6, 1146–1163. [Google Scholar]

- Packiaraj Gurusaravanan, P.G.; Sadasivam Vinoth, S.V.; Kumar, G.P.; Pandiselvi, P. Seaweed Extract Promotes High-Frequency in vitro Regeneration of Solanum surattense Burm.f:A Valuable Medicinal Plant. Res. J. Med. Plants 2017, 11, 134–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vinoth, S.; Gurusaravanan, P.; Sivakumar, S.; Jayabalan, N. Influence of seaweed extracts and plant growth regulators on in vitro regeneration of Lycopersicon esculentum from leaf explant. J. Appl. Phycol. 2019, 31, 2039–2052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jamili, K.M.; Catubis, K.M.L.; Pascual, P.R.L.; Cabillo, R.A. Enhanced growth and yield of eggplant (Solanum melongena L.) applied with seaweed extract. Thai J. Agric. Sci. 2022, 55, 175–184. [Google Scholar]

- Ferreira, A.; Bastos, C.R.V.; Marques-dos-Santos, C.; Acién-Fernandez, F.G.; Gouveia, L. Algaeculture for agriculture: From past to future. Front. Agron. 2023, 5, 1064041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chovanček, E.; Salazar, J.; Şirin, S.; Allahverdiyeva, Y. Microalgae from Nordic collections demonstrate biostimulant effect by enhancing plant growth and photosynthetic performance. Physiol. Plant. 2023, 175, e13911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Piero Estrada, J.E.; Bermejo Bescós, P.; Villar del Fresno, A.M. Antioxidant activity of different fractions of Spirulina platensis protean extract. Il Farm. 2001, 56, 497–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Far, Z.G.; Babajafari, S.; Kojuri, J.; Nouri, M.; Ashrafi-Dehkordi, E.; Mazloomi, S.M. The Effect of Spirulina on Anxiety in Patients with Hypertension: A Randomized Triple-Blind Placebo-Controlled Clinical Trial. J. Nutr. Food Secur. 2022, 7, 181–188. [Google Scholar]

- Parmar, P.; Kumar, R.; Neha, Y.; Srivatsan, V. Microalgae as next generation plant growth additives: Functions, applications, challenges and circular bioeconomy based solutions. Front. Plant Sci. 2023, 14, 1073546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mollo, L.; Petrini, A.; Norici, A.; Ferrante, A.; Cocetta, G. Enhanced growth and photosynthetic efficiency in wild rocket (Diplotaxis tenuifolia L.) following multi-species microalgal biostimulant application. Plant Sci. 2025, 359, 112643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gharib, F.A.E.L.; Osama, K.; El Sattar, A.M.A.; Ahmed, E.Z. Impact of Chlorella vulgaris, Nannochloropsis salina, and Arthrospira platensis as bio-stimulants on common bean plant growth, yield and antioxidant capacity. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 1398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahim, A.; Çakir, C.; Ozturk, M.; Şahin, B.; Soulaimani, A.; Sibaoueih, M.; Nasser, B.; Eddoha, R.; Essamadi, A.; El Amiri, B. Chemical characterization and nutritional value of Spirulina platensis cultivated in natural conditions of Chichaoua region (Morocco). S. Afr. J. Bot. 2021, 141, 235–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| RT (min) | Area, % | Essential Oil Compounds | Molecular Weight (g/mol) | Molecular Formula |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 6.433 | 0.22 | 2,2,3-Trimethylbutane | 100.2 | C7H16 |

| 6.541 | 2.12 | Decane | 142.3 | C10H22 |

| 8.126 | 24.1 | 5-Oxotetrahydrofuran-2-carboxylic acid | 130.1 | C5H6O4 |

| 8.894 | 11.19 | Bis(tert-butyl)diazene | 142.2 | C8H18N2 |

| 9.911 | 1.22 | 2,3-Dihydro-3,5-dihydroxy-6-methyl-4H-pyran-4-one | 144.1 | C6H8O4 |

| 10.243 | 1.33 | Aminoguanidine | 74.1 | CH6N4 |

| 11.202 | 0.29 | Vinyl methacrylate | 112.1 | C6H8O2 |

| 11.317 | 0.6 | 5-Oxotetrahydrofuran-2-carboxylic acid | 130.1 | C5H6O4 |

| 11.716 | 1.38 | Propyl valerate | 144.2 | C8H16O2 |

| 12.47 | 0.2 | Semioxamazide | 75.07 | CH5N3O |

| 13.239 | 0.71 | Propyl valerate | 144.21 | C8H16O2 |

| 13.854 | 2.66 | Methyl 5-oxo-2-pyrrolidinecarboxylate (proline derivative) | 143.1 | C6H9NO3 |

| 14.605 | 2.06 | 1,4-Diacetylbenzene | 162.2 | C10H10O2 |

| 14.725 | 0.26 | Coumarin | 146.1 | C9H6O2 |

| 14.835 | 0.14 | Dimethyl terephthalate | 194.2 | C10H10O4 |

| 15.219 | 0.21 | Dimethyl phthalate | 194.2 | C10H10O4 |

| 15.836 | 1.71 | Methyl dodecanoate (lauric acid methyl ester) | 214.3 | C13H26O2 |

| 16.671 | 0.18 | Dihexyl phthalate | 334.5 | C20H30O4 |

| 16.98 | 0.95 | Methyl-α-D-glucopyranoside | 194.2 | C7H14O6 |

| 17.464 | 0.2 | DL-Tryptophan | 204.2 | C11H12N2O2 |

| 18.31 | 1.72 | Methyl tetradecanoate (myristic acid methyl ester) | 242.4 | C15H30O2 |

| 20.312 | 23.67 | Methyl oleate | 296.5 | C19H36O2 |

| 20.539 | 12.31 | Methyl palmitate | 270.5 | C17H34O2 |

| 20.889 | 2.48 | Palmitic acid | 256.4 | C16H32O2 |

| 22.169 | 1.41 | 1-Nonadecene | 266.5 | C19H38 |

| 22.248 | 1.34 | Methyl linoleate | 294.5 | C19H34O2 |

| 22.568 | 2.34 | Methyl stearate | 298.5 | C19H38O2 |

| 26.176 | 0.57 | Diisooctyl phthalate | 390.6 | C24H38O4 |

| RT (min) | Area, % | Essential Oil Compounds | Molecular Weight (g/mol) | Molecular Formula |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 6.535 | 0.27 | Decane | 142.3 | C10H22 |

| 9.104 | 0.12 | Hexanenitrile | 97.2 | C6H11N |

| 12.143 | 0.53 | Nonanoic acid (pelargonic acid) | 158.2 | C9H18O2 |

| 12.283 | 0.13 | 3-Hepten-1-yl acetate | 156.1 | C9H16O2 |

| 13.883 | 0.77 | Methyl 5-oxo-2-pyrrolidinecarboxylate (proline derivative) | 143.1 | C6H9NO3 |

| 15.838 | 1.25 | Methyl dodecanoate (lauric acid methyl ester) | 214.3 | C13H26O2 |

| 15.983 | 0.22 | Cytosine (4-amino-2-hydroxypyrimidine) | 111.1 | C4H5N3O |

| 17.889 | 1.19 | Cannabigerol-like resorcinol derivative | 316.5 | C21H32O2 |

| 18.313 | 1.34 | Methyl tetradecanoate (myristic acid methyl ester) | 242.4 | C15H30O2 |

| 19.592 | 0.18 | Citronellyl propionate | 212.33 | C13H24O2 |

| 19.646 | 3.13 | Hexahydrofarnesyl acetone | 268.5 | C18H36O |

| 20.315 | 2.16 | Methyl palmitoleate | 268.4 | C17H32O2 |

| 20.541 | 12.08 | Methyl palmitate (hexadecanoic acid, methyl ester) | 270.5 | C17H34O2 |

| 20.661 | 3.88 | Z-9-Tetradecenal | 210.4 | C14H26O |

| 20.897 | 8.82 | Palmitic acid (hexadecanoic acid) | 256.4 | C16H32O2 |

| 21.966 | 0.32 | Methylcrotonic acid | 100.1 | C5H8O2 |

| 22.172 | 1.45 | 1-Pentadecanol | 228.4 | C15H32O |

| 22.249 | 3.06 | Methyl linoleate | 294.5 | C19H34O2 |

| 22.315 | 19.75 | Methyl oleate | 296.5 | C19H36O2 |

| 22.412 | 9.82 | Phytol | 296.5 | C20H40O |

| 22.57 | 3.58 | Methyl stearate | 298.5 | C19H38O2 |

| 22.608 | 2.06 | Methyl linoleate | 294.5 | C19H34O2 |

| 22.666 | 7.92 | Z-9-Hexadecenal | 238.4 | C16H30O |

| 22.895 | 0.31 | Arachidic acid (eicosanoic acid) | 312.5 | C20H40O2 |

| 24.191 | 0.56 | 1,2-Epoxyoctadecane | 268.5 | C18H36O |

| Treatments | Length of the Longest Shoot [cm] | Explant’s Fresh Weight [g] | No. of Shoots/Explant [n] | No. of Leaves/Explant [n] | Callus % | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| S. platensis ( g·L−1) | C. vulgaris (g·L−1) | |||||

| Control | Control | 1.71 ± 0.19 c * | 0.59 ± 0.32 c | 9.71 ± 0.09 f | 34.43 ± 0.48 g | 17.86 ± 0.05 ab |

| 0.5 | 0.0 | 2.67 ± 0.16 ab | 1.21 ± 0.24 a | 17.33 ± 0.47 cd | 61.20 ± 0.42 d | 25.00 ± 0.02 ab |

| 1.0 | 0.0 | 2.07 ± 0.28 b | 0.91 ± 0.17 a | 18.67 ± 0.39 c | 67.20 ± 0.52 c | 16.67 ± 0.06 ab |

| 0.0 | 0.25 | 2.50 ± 0.23 ab | 0.41 ± 0.23 d | 25.67 ± 0.04 b | 60.80 ± 0.36 d | 25.00 ± 0.09 ab |

| 0.0 | 0.5 | 2.60 ± 0.00 ab | 0.76 ± 0.01 b | 34.33 ± 0.20 a | 134.93 ± 0.04 a | 16.67 ± 0.01 ab |

| 0.5 | 0.25 | 2.83 ± 0.02 a | 0.63 ± 0.30 c | 19.17 ± 0.20 c | 71.50 ± 0.27 b | 41.67 ± 0.09 ab |

| 0.5 | 0.5 | 1.75 ± 0.03 c | 0.15 ± 0.22 e | 11.17 ± 0.46 e | 36.50 ± 0.30 g | 16.67 ± 0.03 b |

| 1.0 | 0.25 | 2.17 ± 0.27 b | 0.35 ± 0.35 d | 16.67 ± 0.59 d | 42.17 ± 0.54 f | 41.67 ± 0.09 ab |

| 1.0 | 0.5 | 2.25 ± 0.18 ab | 0.27 ± 0.13 e | 16.17 ± 0.29 d | 45.67 ± 0.15 e | 50.00 ± 0.01 a |

| Compound Name | Wild Plants from the Field | Control (Tissue Culture) | C. vulgaris (0.25 g·L−1) | C. vulgaris (0.5 g·L−1) | S. platensis (0.5 g·L−1) | S. platensis (1.0 g·L−1) | S. platensis (0.5) + C. vulgaris (0.25 g·L−1) | S. platensis (0.5 g·L−1) + C. vulgaris (0.5 g·L−1) | S. platensis (1.0 g·L−1) + C. vulgaris (0.25 g·L−1) | S. platensis (1.0 g·L−1) + C. vulgaris (0.5 g·L−1) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Thymine | 6.97 e * | 6.12 f | 2.61 g | 11.16 c | 5.47 f | 2.44 g | 16.5 a | 6.76 e | 13.8 b | 7.62 d |

| Oxirane, hexadecyl- | 0.68 a | – | – | 0.1 b | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| 4,4,6-Trimethyltetrahydro-1,3-oxazin-2-one | 0.53 b | 0.31 c | 0.23 d | 0.2 d | 0.61 b | 1.67 a | – | – | – | – |

| Dodecanoic acid | 1.52 e | 1.02 e | 0.16 f | 0.79 e | 0.14 f | 0.17 f | 16.82 b | 8.68 d | 19.71 a | 14.64 c |

| Phenol, 2,4-bis(1,1-dimethylethyl)- | 0.41 c | 0.88 a | 0.25 d | 1.02 a | 0.77 a | 0.29 d | – | – | – | – |

| Butanedioic acid, hydroxy-, dimethyl ester | 1.61 a | 1.31 a | 0.67 b | 0.2 c | 0.13 d | 0.31 c | – | – | – | – |

| Dodecanoic acid, methyl ester | 0.57 f | 0.28 g | 0.21 g | 0.7 f | 0.19 g | 0.84 e | 29.27 b | 8.84 d | 19.83 c | 36.68 a |

| Melezitose | 1.31 c | 1.78 b | 0.63 c | 1.05 c | 0.47 d | 0.33 d | – | 7.07 a | – | – |

| Oleic Acid | 0.87 c | 0.29 d | 0.11 d | 0.96 c | 9.16 b | – | 29.44 a | 10.82 b | 31.38 a | 27.72 a |

| 2H-Pyran, 3,4-dihydro- | 2.55 d | 4.52 c | 0.09 g | 15.06 b | 0.19 g | 0.62 f | 20.61 a | 20.14 a | 20.14 a | 21.03 a |

| Phytol | 0.31 f | 0.76 d | 0.21 f | 0.49 d | 0.18 f | 0.32 e | 30.63 a | 11.53 c | 20.45 b | 21.33 b |

| Caryophyllene oxide | 0.91 a | 0.25 b | 0.26 b | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| Myristic acid | 2.85 d | 0.82 f | 0.36 g | 0.54 f | 0.46 f | 1.71 e | – | 14.56 c | 22.16 b | 25.5 a |

| Hexadecanoic acid, methyl ester | 1.83 d | 2.17 d | 1.7 d | 4.85 c | 2.73 d | 1.19 d | – | – | 25.9 a | 16.17 b |

| 1-Nonadecene | 0.69 f | 0.74 f | 0.68 f | 3.81 d | 2.15 e | – | 35.58 a | 12.34 c | 29.67 b | 29.84 b |

| 9-Octadecenoic acid (Z)-, methyl ester | 1.91 g | 3.39 e | 2.9 f | 7.36 d | 4.16 e | 1.74 g | 31.04 b | 34.36 a | 26.8 c | 30.04 b |

| Octadecanoic acid | 2.21 a | 1.26 c | – | 1.88 b | 2.27 a | 0.61 c | – | – | – | – |

| 9,12-Octadecadienoic acid (Z,Z)-, methyl ester | 1.31 c | 1.0 c | 0.39 e | 0.76 d | 2.8 b | 1.26 c | 31.3 a | – | – | – |

| α-D-Glucopyranoside, methyl | 30.73 c | 29.68 c | 2.9 g | 6.74 e | 4.83 f | 43.38 a | 26.21 c | 36.32 b | 21.27 d | 45.33 a |

| Desulphosinigrin | – | 3.93 f | 11.34 d | 1.65 g | 6.22 e | 2.96 f | 24.59 c | 29.12 b | 25.76 c | 32.32 a |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Alrajeh, H.S.; El Sherif, F.; Khattab, S. Application of Spirulina platensis and Chlorella vulgaris for Improved Growth and Bioactive Compound Accumulation in Achillea fragrantissima In Vitro. Phycology 2026, 6, 7. https://doi.org/10.3390/phycology6010007

Alrajeh HS, El Sherif F, Khattab S. Application of Spirulina platensis and Chlorella vulgaris for Improved Growth and Bioactive Compound Accumulation in Achillea fragrantissima In Vitro. Phycology. 2026; 6(1):7. https://doi.org/10.3390/phycology6010007

Chicago/Turabian StyleAlrajeh, Hind Salih, Fadia El Sherif, and Salah Khattab. 2026. "Application of Spirulina platensis and Chlorella vulgaris for Improved Growth and Bioactive Compound Accumulation in Achillea fragrantissima In Vitro" Phycology 6, no. 1: 7. https://doi.org/10.3390/phycology6010007

APA StyleAlrajeh, H. S., El Sherif, F., & Khattab, S. (2026). Application of Spirulina platensis and Chlorella vulgaris for Improved Growth and Bioactive Compound Accumulation in Achillea fragrantissima In Vitro. Phycology, 6(1), 7. https://doi.org/10.3390/phycology6010007