Effectiveness of Interventions to Improve Health Literacy on Medication Use Among Older Adults: A Systematic Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Search Strategy

2.2. Selection Criteria

2.3. Outcome Measures

2.4. Data Extraction

2.5. Quality Assessment

2.6. Data Synthesis and Presentation

3. Results

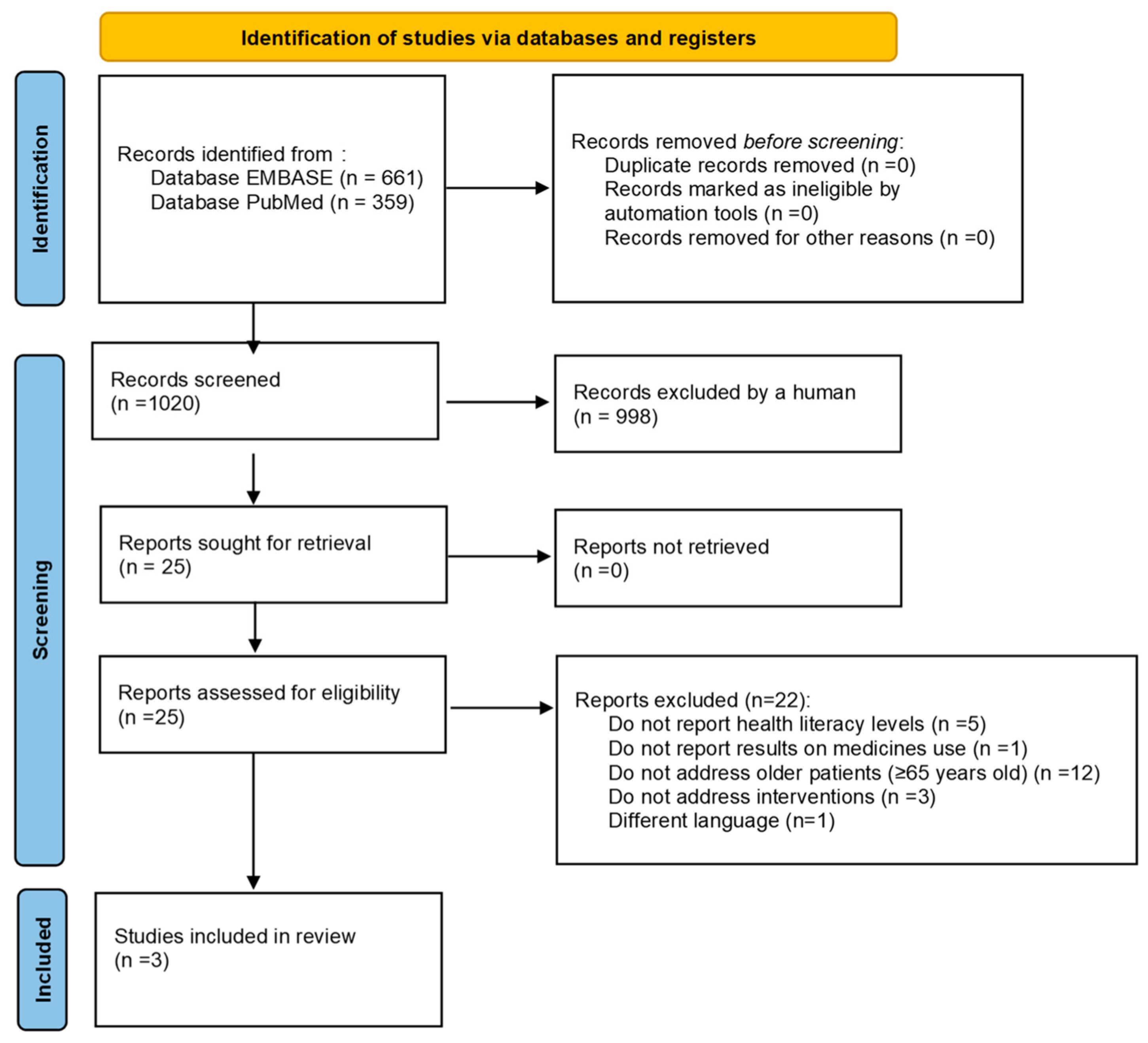

3.1. Study Selection

3.2. Characteristics of Included Studies

3.3. Quality Assessment of Included Studies

3.4. Characteristics of the Interventions and Effects on the Outcomes

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| HL | Health Literacy |

| PRISMA | Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses |

References

- Pedro, A.R.; Amaral, O.; Escoval, A. Literacia Em Saúde, Dos Dados à Ação: Tradução, Validação e Aplicação Do European Health Literacy Survey Em Portugal. Rev. Port. Saúde Pública 2016, 34, 259–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sørensen, K.; Van den Broucke, S.; Pelikan, J.M.; Fullam, J.; Doyle, G.; Slonska, Z.; Kondilis, B.; Stoffels, V.; Osborne, R.H.; Brand, H. Measuring Health Literacy in Populations: Illuminating the Design and Development Process of the European Health Literacy Survey Questionnaire (HLS-EU-Q). BMC Public Health 2013, 13, 948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, N.J.; Terry, A.; McHorney, C.A. Impact of Health Literacy on Medication Adherence. Ann. Pharmacother. 2014, 48, 741–751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Geboers, B.; Brainard, J.S.; Loke, Y.K.; Jansen, C.J.M.; Salter, C.; Reijneveld, S.A.; de Winter, A.F. The Association of Health Literacy with Adherence in Older Adults, and Its Role in Interventions: A Systematic Meta-Review. BMC Public Health 2015, 15, 903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Costa, A.; Feteira-Santos, R.; Alarcão, V.; Henriques, A.; Madeira, T.; Virgolino, A.; Arriaga, M.; Nogueira, P.J. Health Literacy among Older Adults in Portugal and Associated Sociodemographic, Health and Healthcare-Related Factors. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 4172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lima, A.C.P.; Maximiano-Barreto, M.A.; Martins, T.C.R.; Luchesi, B.M. Factors Associated with Poor Health Literacy in Older Adults: A Systematic Review. Geriatr. Nurs. 2024, 55, 242–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geboers, B.; de Winter, A.F.; Spoorenberg, S.L.W.; Wynia, K.; Reijneveld, S.A. The Association between Health Literacy and Self-Management Abilities in Adults Aged 75 and Older, and Its Moderators. Qual. Life Res. 2016, 25, 2869–2877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, T.A. Health Literacy and Adherence to Medical Treatment in Chronic and Acute Illness: A Meta-Analysis. Patient Educ. Couns. 2016, 99, 1079–1086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schönfeld, M.S.; Pfisterer-Heise, S.; Bergelt, C. Self-Reported Health Literacy and Medication Adherence in Older Adults: A Systematic Review. BMJ Open 2021, 11, e056307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, B.; Yu, S. Effect of Whole-Course Medication Education Method on Drug Literacy and Complications of Elderly Patients with Coronary Heart Disease after Percutaneous Coronary Intervention. Acta Medica Mediterr. 2022, 38, 3531–3537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Medication Safety in Polypharmacy. Available online: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/WHO-UHC-SDS-2019.11 (accessed on 20 February 2023).

- Mirczak, A. Functional, Communicative and Critical Health Literacy among Older Polish Citizens. Med. Pracy. Work. Health Saf. 2022, 73, 191–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marshall, N.; Butler, M.; Lambert, V.; Timon, C.M.; Joyce, D.; Warters, A. Health Literacy Interventions and Health Literacy-Related Outcomes for Older Adults: A Systematic Review. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2025, 25, 319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, Q.; Liu, T.; Liu, R.; Yang, H.; Liu, C. Effectiveness of Digital Health Literacy Interventions in Older Adults: Single-Arm Meta-Analysis. J. Med. Internet Res. 2023, 25, e48166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cross, A.J.; Elliott, R.A.; George, J. Interventions for Improving Medication-Taking Ability and Adherence in Older Adults Prescribed Multiple Medications. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2016, 2016, CD012419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stormacq, C.; Wosinski, J.; Boillat, E.; Van den Broucke, S. Effects of Health Literacy Interventions on Health-Related Outcomes in Socioeconomically Disadvantaged Adults Living in the Community: A Systematic Review. JBI Evid. Synth. 2020, 18, 1389–1469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wali, H.; Hudani, Z.; Wali, S.; Mercer, K.; Grindrod, K. A Systematic Review of Interventions to Improve Medication Information for Low Health Literate Populations. Res. Soc. Adm. Pharm. 2016, 12, 830–864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kickbusch, I.; Pelikan, J.M.; Apfel, F.; Tsouros, A.D. Health Literacy: The Solid Facts; Kickbusch, I., Pelikan, J.M., Apfel, F., Tsouros, A.D., Eds.; World Health Organization Regional Office for Europe: Copenhagen, Danmark, 2013.

- Arriaga, M.; Francisco, R.; Nogueira, P.; Oliveira, J.; Silva, C.; Câmara, G.; Sørensen, K.; Dietscher, C.; Costa, A. Health Literacy in Portugal: Results of the Health Literacy Population Survey Project 2019–2021. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 4225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faulkner, L.; Hughes, C.M.; Barry, H.E. Interventions to Improve Medicines Optimisation in Older People with Frailty in Primary Care: A Systematic Review. Int. J. Pharm. Pract. 2022, 30, 297–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 Statement: An Updated Guideline for Reporting Systematic Reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ouzzani, M.; Hammady, H.; Fedorowicz, Z.; Elmagarmid, A. Rayyan—A Web and Mobile App for Systematic Reviews. Syst. Rev. 2016, 5, 210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Health Laboratory. Study Quality Assessment Tools. Available online: https://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/health-topics/study-quality-assessment-tools (accessed on 12 July 2024).

- The Joanna Briggs Institute. Checklist for Quasi-Experimental (Non-Randomized Experimental Studies; The Joanna Briggs Institute: Adelaide, Australia, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Ng, A.W.Y.; Chan, A.H.S.; Ho, V.W.S. Comprehension by Older People of Medication Information with or without Supplementary Pharmaceutical Pictograms. Appl. Ergon. 2017, 58, 167–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grice, G.R.; Tiemeier, A.; Hurd, P.; Berry, T.M.; Voorhees, M.; Prosser, T.R.; Sailors, J.; Gattas, N.M.; Duncan, W. Student Use of Health Literacy Tools to Improve Patient Understanding and Medication Adherence. Consult. Pharm. 2014, 29, 240–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miller, T.; Reihlen, M. Assessing the Impact of Patient-Involvement Healthcare Strategies on Patients, Providers, and the Healthcare System: A Systematic Review. Patient Educ. Couns. 2023, 110, 107652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, L.; Zhang, R.; Chen, Y.; Deng, H.; Liu, S.; Wang, G.; Wang, M.; Liang, S.; Xing, W.; Lin, H.; et al. Achievements and Challenges in Health Management for Aged Individuals in Primary Health Care Sectors: A Survey in Southwest China. BMC Public Health 2020, 20, 338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vogler, C.; Arnoldi, J.; Moose, H.; Hingle, S.T. Interprofessional Education Involving Medical and Pharmacy Students during Transitions of Care. J. Interprof. Care 2017, 31, 404–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saragih, I.D.; Hsiao, C.T.; Fann, W.C.; Hsu, C.M.; Saragih, I.S.; Lee, B.O. Impacts of Interprofessional Education on Collaborative Practice of Healthcare Professionals: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Nurse Educ. Today 2024, 136, 106136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malhotra, R.; Suppiah, S.; Tan, Y.W.; Tay, S.S.C.; Tan, V.S.Y.; Tang, W.-E.; Tan, N.C.; Wong, R.Y.H.; Chan, A.; Koh, G.C.-H.; et al. Validation of Pharmaceutical Pictograms among Older Adults with Limited English Proficiency. Patient Educ. Couns. 2022, 105, 909–916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bailey, S.C.; Wismer, G.A.; Parker, R.M.; Walton, S.M.; Wood, A.J.J.; Wallia, A.; Brokenshire, S.A.; Infanzon, A.C.; Curtis, L.M.; Kwasny, M.J.; et al. Development and Rationale for a Multifactorial, Randomized Controlled Trial to Test Strategies to Promote Adherence to Complex Drug Regimens among Older Adults. Contemp. Clin. Trials 2017, 62, 21–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forbes, R.; Clasper, B.; Ilango, A.; Kan, H.; Peng, J.; Mandrusiak, A. Effectiveness of Patient Education Training on Health Professional Student Performance: A Systematic Review. Patient Educ. Couns. 2021, 104, 2453–2466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, W.; O’Reilly, C.L.; Moles, R.J.; Robinson, J.D.; Brand-Eubanks, D.; Kim, A.P.; El-Den, S. A Systematic Review of Patient Interactions with Student Pharmacists in Educational Settings. J. Am. Pharm. Assoc. 2021, 61, 678–693.e3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cocchieri, A.; Pezzullo, A.M.; Cesare, M.; De Rinaldis, M.; Cristofori, E.; D’Agostino, F. Association between Health Literacy and Nursing Care in Hospital: A Retrospective Study. J. Clin. Nurs. 2024, 33, 642–652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xin, Y.; Weina, H.; Yan, D. Digital Literacy Impacts Quality of Life among Older Adults through Hierarchical Mediating Mechanisms. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 19288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.; Park, C.; Park, S.; Kim, D.-J.; Bae, Y.-S.; Kang, J.-H.; Chun, J.-W. Measuring Digital Health Literacy in Older Adults: Development and Validation Study. J. Med. Internet Res. 2025, 27, e65492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, Z.; Du, X.; Li, J.; Hou, R.; Sun, J.; Marohabutr, T. Factors Influencing Digital Health Literacy among Older Adults: A Scoping Review. Front. Public Health 2024, 12, 1447747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gregório, J.; Maricoto, T.; Moreira, P.A.S.; Roque, F.; Correia-de-Sousa, J.; Herdeiro, M.T.; Almeida, I.F.; Tsiligiann, I.; Agh, T.; Jácome, C. Addressing the digital divide: Who is being left behind in the evaluation of e-Health interventions to improve medication adherence? Biomed. Biopharm. Res. 2024, 20, 93–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Author, Year | Country | Study Design | Setting | Specific Disease | Older Patients Sample | Comparator | Quality Assessment * | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sample Size | Age | |||||||

| Chen et al., 2022 [10] | China | RCT | Post-discharge | Coronary heart disease | 116 (C:58 I:58) | ≥65 years old | Patients with routine drug education | 12/14 a |

| Ng et al., 2017 [25] | China | Non-RCT | community | - | 50 (C:25 I:25) | ≥65 years old | Without intervention/usual care | 5/9 b |

| Grice et al., 2014 [26] | USA | Pre–Post Intervention Study | independent-living senior facilities | - | 2009–2010-159; 2010–2011-147; 2011–2012-153 | seniors | Without comparator | 4/12 c |

| Author, Year | Performed by | Type of Intervention | HL Measure Tool | Medication Measure Tool | Outcome Measures | Significant Outcomes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chen et al., 2022 [10] | Medical staff | Continuous education and clinical follow-up | Drug literacy questionnaire compiled by Maniaci et al. | Drug literacy questionnaire compiled by Maniaci et al. | Evaluation of Pharmacological Literacy and complications, and readmission rates were monitored and compared between the two groups. | Before the intervention: no significant differences in drug literacy scores between groups (p > 0.05); after 1 and 3 months: education group scores were significantly higher than the routine group (p < 0.05); rate of administration errors in education group was 5.17%, lower than routine group (15.52%) (p < 0.05); incidences of complications and readmissions: lower in the education group (p < 0.05). |

| Ng et al., 2017 [25] | Pharmacists | Textual labels with pictograms | REALM-R (Rapid Estimate of Adult Literacy in medicine-Revised Test) | Medication information comprehension scoring criteria | Medical information comprehension scores for different labels for the control group (text only) and experimental group (text and pictogram) | Comprehension scores: higher for the experimental group (p = 0.023) |

| Grice et al., 2014 [26] | Pharmacy students | Communication facilitated by students | Four Habits Model (FHM) Teach-back, Ask Me 3™, Plain Language, and universal Precautions | - | Resident and student satisfaction with the program, correlations between the students’ use of HL tools and overall residents and students’ satisfaction and between student use of HL tools and resident satisfaction. | Residents’ overall satisfaction with the program, increased understanding of health-related information, confidence in asking healthcare professionals questions about their health, and greater commitment to medication adherence; students highly satisfied with the program. Correlations between previously determined performance level of student communication and resident satisfaction. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Perpétuo, C.; Plácido, A.I.; Mateos-Campos, R.; Figueiras, A.; Herdeiro, M.T.; Roque, F. Effectiveness of Interventions to Improve Health Literacy on Medication Use Among Older Adults: A Systematic Review. J. Ageing Longev. 2025, 5, 47. https://doi.org/10.3390/jal5040047

Perpétuo C, Plácido AI, Mateos-Campos R, Figueiras A, Herdeiro MT, Roque F. Effectiveness of Interventions to Improve Health Literacy on Medication Use Among Older Adults: A Systematic Review. Journal of Ageing and Longevity. 2025; 5(4):47. https://doi.org/10.3390/jal5040047

Chicago/Turabian StylePerpétuo, Carla, Ana I. Plácido, Ramona Mateos-Campos, Adolfo Figueiras, Maria Teresa Herdeiro, and Fátima Roque. 2025. "Effectiveness of Interventions to Improve Health Literacy on Medication Use Among Older Adults: A Systematic Review" Journal of Ageing and Longevity 5, no. 4: 47. https://doi.org/10.3390/jal5040047

APA StylePerpétuo, C., Plácido, A. I., Mateos-Campos, R., Figueiras, A., Herdeiro, M. T., & Roque, F. (2025). Effectiveness of Interventions to Improve Health Literacy on Medication Use Among Older Adults: A Systematic Review. Journal of Ageing and Longevity, 5(4), 47. https://doi.org/10.3390/jal5040047