Geriatric Suicide: Understanding Risk Factors and Prevention Strategies Using a Socioecological Model

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Method

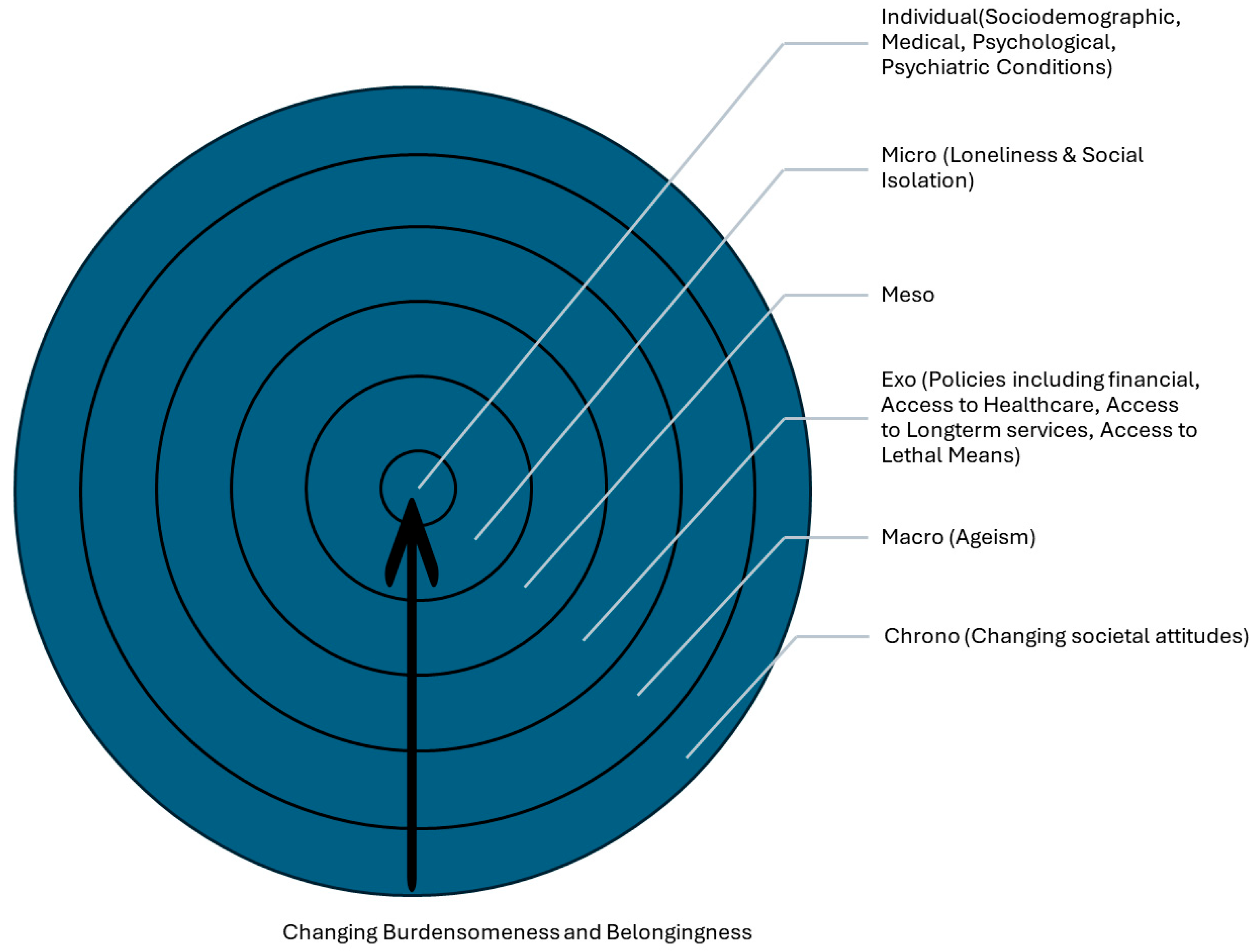

- Individual-level factors: sociodemographic characteristics, physical health conditions, and psychiatric/psychological conditions.

- External factors (micro, meso, exo, macro and chrono): interpersonal relationships, organizational influences, policy-related determinants, societal and cultural factors.

Study Selection and Data Synthesis

3. Risk Factors

3.1. Individual Factors

3.1.1. Sociodemographic Factors

3.1.2. Cognitive and Physical Health Issues

3.1.3. Psychiatric Disorders

3.1.4. Psychological Determinants

3.2. External Factors

3.2.1. Interpersonal

3.2.2. Organizational

3.2.3. Policy

3.2.4. Culture and Society (And Time)

4. Interventions to Reduce Suicide Risk

4.1. Individual

4.2. Interpersonal

4.3. Organizational and Policy

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- World Health Organization. Suicide; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Garnett, M.F.; Spencer, M.R.; Weeks, J.D. Suicide Among Adults Age 55 and Older, 2021; NCHS Data Brief. No. 483; National Center for Health Statistics: Hyattsville, MD, USA, 2023.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Suicide Data and Statistics. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/suicide/suicide-data-statistics.html (accessed on 22 June 2025).

- Choi, N.G.; DiNitto, D.M.; Marti, C.N.; Kaplan, M.S. Older Suicide Decedents: Intent Disclosure, Mental and Physical Health, and Suicide Means. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2017, 53, 772–780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Leo, D. Late-life suicide in an aging world. Nat. Aging 2022, 2, 7–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, J.; Ouyang, F.; Qiu, D.; Li, L.; Li, Y.; Xiao, S. Time Trends and Predictions of Suicide Mortality for People Aged 70 Years and Over From 1990 to 2030 Based on the Global Burden of Disease Study 2017. Front. Psychiatry 2021, 12, 721343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United States Census Bureau. 2023 National Population Projections Tables: Main Series; United States Census Bureau: Suitland, MA, USA, 2023. Available online: https://www.census.gov/data/tables/2023/demo/popproj/2023-summary-tables.html (accessed on 18 May 2025).

- Kushner, H.I.; Sterk, C.E. The Limits of Social Capital: Durkheim, Suicide, and Social Cohesion. Am. J. Public Health 2005, 95, 1139–1143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shira, B.; Lawrence, O.C. Psychological Models of Suicide. In The Suicidal Crisis: Clinical Guide to the Assessment of Imminent Suicide Risk, 2nd ed.; Oxford Academic: New York, NY, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Wenzel, A.; Beck, A.T. A cognitive model of suicidal behavior: Theory and treatment. Appl. Prev. Psychol. 2008, 12, 189–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joiner, T.E.; Van Orden, K.A.; Witte, T.K.; Selby, E.A.; Ribeiro, J.D.; Lewis, R.; Rudd, M.D. Main predictions of the interpersonal–psychological theory of suicidal behavior: Empirical tests in two samples of young adults. J. Abnorm. Psychol. 2009, 118, 634–646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rubinstein, D.H. A stress-diathesis theory of suicide. Suicide Life-Threat. Behav. 1986, 16, 182–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bronfenbrenner, U. Toward an experimental ecology of human development. Am. Psychol. 1977, 32, 513–531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shneidman, E.S. A psychological approach to suicide. In Cataclysms, Crises, and Catastrophes: Psychology in Action; VandenBos, G.R., Bryant, B.K., Eds.; American Psychological Association: Washington, DC, USA, 1987; pp. 147–183. [Google Scholar]

- Chu, C.; Buchman-Schmitt, J.M.; Stanley, I.H.; Hom, M.A.; Tucker, R.P.; Hagan, C.R.; Rogers, M.L.; Podlogar, M.C.; Chiurliza, B.; Ringer, F.B.; et al. The interpersonal theory of suicide: A systematic review and meta-analysis of a decade of cross-national research. Psychol. Bull. 2017, 143, 1313–1345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beghi, M.; Butera, E.; Cerri, C.G.; Cornaggia, C.M.; Febbo, F.; Mollica, A.; Berardino, G.; Piscitelli, D.; Resta, E.; Logroscino, G.; et al. Suicidal behaviour in older age: A systematic review of risk factors associated to suicide attempts and completed suicides. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 2021, 127, 193–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zimmerman, G.M.; Fridel, E.E.; Trovato, D. Disproportionate burden of violence: Explaining racial and ethnic disparities in potential years of life lost among homicide victims, suicide decedents, and homicide-suicide perpetrators. PLoS ONE 2024, 19, e0297346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- El Ibrahimi, S.; Xiao, Y.; Bergeron, C.D.; Beckford, N.Y.; Virgen, E.M.; Smith, M.L. Suicide Distribution and Trends Among Male Older Adults in the U.S., 1999–2018. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2021, 60, 802–811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goldsmith, S.K. Society and culture. In Reducing Suicide: A National Imperative; Goldsmith, S.K., Pellmar, T.C., Kleinman, A.M., Bunney, W.E., Eds.; National Academies Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2002. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK220948/ (accessed on 18 May 2025).

- Dhole, A.R.; Petkar, P.; Choudhari, S.G.; Mendhe, H.; Petkar, D. Understanding the Factors Contributing to Suicide Among the Geriatric Population: A Narrative Review. Cureus 2023, 15, e46387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitchell, O.; Lusardi, A. Remaking Retirement: Debt in an Aging Economy; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, L.; Shin, J.I.; Carmichael, C.; Jacob, L.; Kostev, K.; Grabovac, I.; Barnett, Y.; Butler, L.; Lindsay, R.K.; Pizzol, D.; et al. Association of food insecurity with suicidal ideation and suicide attempts in adults aged ≥50 years from low- and middle-income countries. J. Affect. Disord. 2022, 309, 446–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kułak-Bejda, A.; Bejda, G.; Waszkiewicz, N. Mental Disorders, Cognitive Impairment and the Risk of Suicide in Older Adults. Front. Psychiatry 2021, 12, 695286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmutte, T.; Olfson, M.; Maust, D.T.; Xie, M.; Marcus, S.C. Suicide risk in first year after dementia diagnosis in older adults. Alzheimer’s Dement. 2021, 18, 262–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richard-Devantoy, S.; Szanto, K.; Butters, M.; Kalkus, J.; Dombrovski, A. Cognitive inhibition in elderly high-lethality suicide attempters. Eur. Psychiatry 2015, 30, 1793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villarejo-Galende, A.; García-Arcelay, E.; Piñol-Ripoll, G.; del Olmo-Rodríguez, A.; Viñuela, F.; Boada, M.; Franco-Macías, E.; de la Peña, A.I.; Riverol, M.; Puig-Pijoan, A.; et al. Awareness of Diagnosis in Persons with Early-Stage Alzheimer’s Disease: An Observational Study in Spain. Neurol. Ther. 2022, 11, 1183–1192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juurlink, D.N.; Herrmann, N.; Szalai, J.P.; Kopp, A.; Redelmeier, D.A. Medical Illness and the Risk of Suicide in the Elderly. Arch. Intern. Med. 2004, 164, 1179–1184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Older Adults: Chronic Disease Indicators; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC): Atlanta, GA, USA, 2024. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/cdi/indicators/older-adults.html (accessed on 18 May 2025).

- Kim, Y.A.; Bogner, H.R.; Brown, G.K.; Gallo, J.J. Chronic Medical Conditions and Wishes to Die among Older Primary Care Patients. Int. J. Psychiatry Med. 2006, 36, 183–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erlangsen, A.; Stenager, E.; Conwell, Y. Physical diseases as predictors of suicide in older adults: A nationwide, register-based cohort study. Soc. Psychiatry Psychiatr. Epidemiol. 2015, 50, 1427–1439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, C.H.; Chen, S.J.; Liu, C.Y.; Tsai, H.C. Suicidal drug overdose following stroke in elderly patients: A retrospective population-based cohort study. Neuropsychiatr. Dis. Treat. 2018, 14, 443–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmedani, B.K.; Peterson, E.L.; Hu, Y.; Rossom, R.C.; Lynch, F.; Lu, C.Y.; Waitzfelder, B.E.; Owen-Smith, A.A.; Hubley, S.; Prabhakar, D.; et al. Major Physical Health Conditions and Risk of Suicide. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2017, 53, 308–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheatle, M.D.; Wasser, T.; Foster, C.; Olugbodi, A.; Bryan, J. Prevalence of suicidal ideation in patients with chronic non-cancer pain referred to a behaviorally based pain program. Pain Physician 2014, 17, E359–E367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edwards, R.R.; Smith, M.T.; Kudel, I.; Haythornthwaite, J. Pain-related catastrophizing as a risk factor for suicidal ideation in chronic pain. Pain 2006, 126, 272–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ratcliffe, G.E.; Enns, M.W.; Belik, S.L.; Sareen, J. Chronic pain conditions and suicidal ideation and suicide attempts: An epidemiologic perspective. Clin. J. Pain 2008, 24, 204–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Themelis, K.; Gillett, J.L.; Karadag, P.; Cheatle, M.D.; Giordano, N.A.; Balasubramanian, S.; Singh, S.P.; Tang, N.K. Mental Defeat and Suicidality in Chronic Pain: A Prospective Analysis. J. Pain 2023, 24, 100587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, J.; Martins, S.; Azevedo, L.F.; Fernandes, L. Pain as a risk factor for suicidal behavior in older adults: A systematic review. Arch. Gerontol. Geriatr. 2020, 87, 104000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gayman, M.D.; Brown, R.L.; Cui, M. Depressive symptoms and bodily pain: The role of physical disability and social stress. Stress Health 2011, 27, 52–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anguiano, L.; Mayer, D.K.; Piven, M.L.; Rosenstein, D. A Literature Review of Suicide in Cancer Patients. Cancer Nurs. 2012, 35, E14–E26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Potter, A.L.; Haridas, C.; Neumann, K.; Kiang, M.V.; Fong, Z.V.; Riddell, C.A.; Pope, H.G.; Yang, C.-F.J. Incidence, Timing, and Factors Associated with Suicide Among Patients Undergoing Surgery for Cancer in the US. JAMA Oncol. 2023, 9, 308–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saad, A.M.; Gad, M.M.; Al-Husseini, M.J.; AlKhayat, M.A.; Rachid, A.; Alfaar, A.S.; Hamoda, H.M. Suicidal death within a year of a cancer diagnosis: A population-based study. Cancer 2019, 125, 972–979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Qiu, X.; Yang, X.; Mao, J.; Li, Q. Factors Influencing Social Isolation among Cancer Patients: A Systematic Review. Healthcare 2024, 12, 1042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chesney, E.; Goodwin, G.M.; Fazel, S. Risks of all-cause and suicide mortality in mental disorders: A meta-review. World Psychiatry 2014, 13, 153–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Obuobi-Donkor, G.; Nkire, N.; Agyapong, V.I.O. Prevalence of Major Depressive Disorder and Correlates of Thoughts of Death, Suicidal Behaviour, and Death by Suicide in the Geriatric Population—A General Review of Literature. Behav. Sci. 2021, 11, 142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lenze, E.J.; Mulsant, B.H.; Shear, M.K.; Schulberg, H.C.; Dew, M.A.; Begley, A.E.; Pollock, B.G.; Reynolds, C.F. Comorbid Anxiety Disorders in Depressed Elderly Patients. Am. J. Psychiatry 2000, 157, 722–728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bakkane Bendixen, A.; Engedal, K.; Selbæk, G.; Hartberg, C.B. Anxiety symptoms in older adults with depression are associated with suicidality. Dement. Geriatr. Cogn. Disord. 2018, 45, 180–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wærn, M.; Runeson, B.S.; Allebeck, P.; Beskow, J.; Rubenowitz, E.; Skoog, I.; Wilhelmsson, K. Mental Disorder in Elderly Suicides: A Case-Control Study. Am. J. Psychiatry 2002, 159, 450–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cornaggia, C.M.; Beghi, M.; Rosenbaum, J.F.; Cerri, C. Risk factors for fatal and nonfatal repetition of suicide attempts: A literature review. Neuropsychiatr. Dis. Treat. 2013, 9, 1725–1736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mezuk, B.; Lohman, M. Suicide rates are high and rising among older adults in the US. Health Aff. 2023, 42, 507–514. [Google Scholar]

- Lykouras, L.; Gournellis, R. Depression in the elderly. Ann. Gen. Psychiatry 2008, 7, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bossé, C.; Préville, M.; Vasiliadis, H.-M.; Béland, S.-G.; Lapierre, S.; Scientific Committee of the ESA Study. Suicidal Ideation, Death Thoughts, and Use of Benzodiazepines in the Elderly Population. Can. J. Community Ment. Health 2011, 30, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Favril, L.; Yu, R.; Uyar, A.; Sharpe, M.; Fazel, S. Risk factors for suicide in adults: Systematic review and meta-analysis of psychological autopsy studies. Évid. Based Ment. Health 2022, 25, 148–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blow, F.C.; Brockmann, L.M.; Barry, K.L. Role of Alcohol in Late-Life Suicide. Alcohol. Clin. Exp. Res. 2004, 28, 48S–56S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morin, J.; Wiktorsson, S.; Marlow, T.; Olesen, P.J.; Skoog, I.; Waern, M. Alcohol Use Disorder in Elderly Suicide Attempters: A Comparison Study. Am. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry 2013, 21, 196–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pompili, M.; Serafini, G.; Innamorati, M.; Dominici, G.; Ferracuti, S.; Kotzalidis, G.D.; Serra, G.; Girardi, P.; Janiri, L.; Tatarelli, R.; et al. Suicidal Behavior and Alcohol Abuse. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2010, 7, 1392–1431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jeste, D.V.; Blazer, D.G.; First, M. Aging-Related Diagnostic Variations: Need for Diagnostic Criteria Appropriate for Elderly Psychiatric Patients. Biol. Psychiatry 2005, 58, 265–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laranjeira, C.; Querido, A. Hope and optimism as an opportunity to improve the “positive mental health” demand. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 827320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beck, A.T.; Brown, G.; Berchick, R.J.; Stewart, B.L.; Steer, R.A. Relationship Between Hopelessness and Ultimate Suicide: A Replication with Psychiatric Outpatients. Focus 2006, 4, 291–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luthar, S.S.; Cicchetti, D.; Becker, B. The Construct of Resilience: A Critical Evaluation and Guidelines for Future Work. Child Dev. 2000, 71, 543–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, J.; Wood, A.M.; Gooding, P.; Taylor, P.J.; Tarrier, N. Resilience to suicidality: The buffering hypothesis. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 2011, 31, 563–591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gooding, P.A.; Hurst, A.; Johnson, J.; Tarrier, N. Psychological resilience in young and older adults. Int. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry 2011, 27, 262–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heisel, M.J.; Flett, G.L. Purpose in Life, Satisfaction with Life, and Suicide Ideation in a Clinical Sample. J. Psychopathol. Behav. Assess. 2004, 26, 127–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fischer, I.C.; Nichter, B.; Feldman, D.B.; Na, P.J.; Tsai, J.; Harpaz-Rotem, I.; Schulenberg, S.E.; Pietrzak, R.H. Purpose in life protects against the development of suicidal thoughts and behaviors in U.S. veterans without a history of suicidality: A 10-year, nationally representative, longitudinal study. J. Affect. Disord. 2023, 340, 551–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ohiokpehai, J.; Gammack, J.K.; Siddiqui, M.; Nyahoda, T. Loneliness and Social Isolation in Older Adults. Mo. Med. 2025, 122, 118–123. [Google Scholar]

- Hajek, A.; Sutin, A.R.; Posi, G.; Stephan, Y.; Peltzer, K.; Terracciano, A.; Luchetti, M.; König, H.-H. Chronic loneliness and chronic social isolation among older adults. A systematic review, meta-analysis and meta-regression. Aging Ment. Health 2024, 29, 185–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leigh-Hunt, N.; Bagguley, D.; Bash, K.; Turner, V.; Turnbull, S.; Valtorta, N.; Caan, W. An overview of systematic reviews on the public health consequences of social isolation and loneliness. Public Health 2017, 152, 157–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hoogendijk, E.O.; Smit, A.P.; van Dam, C.; Schuster, N.A.; de Breij, S.; Holwerda, T.J.; Huisman, M.; Dent, E.; Andrew, M.K. Frailty Combined with Loneliness or Social Isolation: An Elevated Risk for Mortality in Later Life. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 2020, 68, 2587–2593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. Social Isolation and Loneliness in Older Adults: Opportunities for the Health Care System; The National Academies Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Müller, J.; Elsaesser, M.; Berger, R.; Müller, W.; Hellmich, M.; Zehender, N.; Riedel-Heller, S.; Bewernick, B.H.; Wagner, M.; Frölich, L.; et al. The Impact of Loneliness on Late-Life Depression and Anxiety During the COVID-19 Pandemic. Am. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry 2025, 33, 717–729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jain, S.; Dhall, M. Social isolation in COVID-19: Impact of loneliness and NCDs on mental and physical health of older adults. In Handbook of Aging, Health and Public Policy; Bloom, D.E., Ed.; Springer: Singapore, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Unsar, S.; Erol, O.; Sut, N. Social Support and Quality of Life Among Older Adults. Int. J. Caring Sci. 2016, 9, 249–257. [Google Scholar]

- Wand, A.P.F.; Zhong, B.-L.; Chiu, H.F.K.; Draper, B.; De Leo, D. COVID-19: The implications for suicide in older adults. Int. Psychogeriatr. 2020, 32, 1225–1230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drageset, J. Social support. In Health Promotion in Health Care: Vital Theories and Research; Haugan, G., Eriksson, M., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2021; Chapter 11. [Google Scholar]

- Gerlach, L.B.; Solway, E.S.; Malani, P.N. Social Isolation and Loneliness in Older Adults. J. Am. Med. Assoc. 2024, 331, 2058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brausch, A.M.; Decker, K.M. Self-Esteem and Social Support as Moderators of Depression, Body Image, and Disordered Eating for Suicidal Ideation in Adolescents. J. Abnorm. Child Psychol. 2013, 42, 779–789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harrison, K.E.; Dombrovski, A.Y.; Morse, J.Q.; Houck, P.; Schlernitzauer, M.; Reynolds, C.F.; Szanto, K. Alone? Percieved social support and chronic interpersonal difficulties in suicidal elders. Int. Psychogeriatr. 2009, 22, 445–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Farrell, T.W.; Korniyenko, A.; Hu, G.; Fulmer, T. Geriatric medicine is advancing, not declining: A proposal for new metrics to assess the health of the profession. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 2024, 73, 323–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AARP Policy Institute. Innovation and Opportunity: 2023 Long-Term Services and Supports State Scorecard; AARP Policy Institute: Washington, DC, USA, 2023; Available online: https://ltsschoices.aarp.org/scorecard-report/innovation-and-opportunity (accessed on 18 May 2025).

- KFF. Payment Rates for Medicaid Home- and Community-Based Services: States’ Responses to Workforce Challenges; KFF: San Francisco, CA, USA, 2023; Available online: https://www.kff.org/medicaid/issue-brief/payment-rates-for-medicaid-home-and-community-based-services-states-responses-to-workforce-challenges/ (accessed on 18 May 2025).

- Centers for Disease Control Prevention (CDC). Suicide Self-Harm Deaths in the United States 2000–2021; NCHS Data Brief No 483; National Center for Health Statistics: Hyattsville, MD, USA, 2023. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/products/databriefs/db483.htm (accessed on 18 May 2025).

- Conwell, Y.; Duberstein, P.R.; Connor, K.; Eberly, S.; Cox, C.; Caine, E.D. Access to Firearms and Risk for Suicide in Middle-Aged and Older Adults. Am. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry 2002, 10, 407–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doak, M.W.; Nixon, A.C.; Lupton, D.J.; Waring, W.S. Self-poisoning in older adults: Patterns of drug ingestion and clinical outcomes. Age Ageing 2009, 38, 407–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diego, D.L. Ageism and suicide prevention. Lancet Psychiatry 2018, 5, 192–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Orden, K.; Deming, C. Late-life suicide prevention strategies: Current status and future directions. Curr. Opin. Psychol. 2018, 22, 79–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vauclair, C.; Hanke, K.; Huang, L.; Abrams, D. Are Asian cultures really less ageist than Western ones? It depends on the questions asked. Int. J. Psychol. 2016, 52, 136–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- North, M.S.; Fiske, S.T. Modern attitudes toward older adults in the aging world: A cross-cultural meta-analysis. Psychol. Bull. 2015, 141, 993–1021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chang, E.S.; Kannoth, S.; Levy, S.; Wang, S.Y.; Lee, J.E.; Levy, B.R. Global reach of ageism on older persons’ health: A systematic review. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0220857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gendron, T.; Camp, A.; Amateau, G.; Iwanaga, K. Internalized ageism as a risk factor for suicidal ideation in later life. Aging Ment. Health 2024, 28, 701–705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urtamo, A.; Jyväkorpi, S.K.; Strandberg, T.E. Definitions of successful ageing: A brief review of a multidimensional concept. Acta Biomed. 2019, 90, 359–363. [Google Scholar]

- Lapierre, S.; Erlangsen, A.; Waern, M.; De Leo, D.; Oyama, H.; Scocco, P.; Gallo, J.; Szanto, K.; Conwell, Y.; Draper, B.; et al. A systematic review of elderly suicide prevention programs. Crisis 2011, 32, 88–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodrigues, C.E.; Grandt, C.L.; Abu Alwafa, R.; Badrasawi, M.; Aleksandrova, K. Determinants and indicators of successful aging as a multidimensional outcome: A systematic review of longitudinal studies. Front. Public Health 2023, 11, 1258280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burton, E.; Teater, B.; Chonody, J.; Alford, S. What Does It Mean to Successfully Age?: Multinational Study of Older Adults’ Perceptions. Gerontologist 2024, 64, gnae102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conwell, Y.; Van Orden, K.; Caine, E.D. Suicide in Older Adults. Psychiatr. Clin. N. Am. 2011, 34, 451–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.-U.; Park, J.-I.; Lee, S.; Oh, I.-H.; Choi, J.-M.; Oh, C.-M. Changing trends in suicide rates in South Korea from 1993 to 2016: A descriptive study. BMJ Open 2018, 8, e023144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conwell, Y.; Duberstein, P.R. Suicide in Elders. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2001, 932, 132–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Skultety, K.M.; Rodriguez, R.L. Treating geriatric depression in primary care. Curr. Psychiatry Rep. 2008, 10, 44–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cougnard, A.; Verdoux, H.; Grolleau, A.; Moride, Y.; Begaud, B.; Tournier, M. Impact of antidepressants on the risk of suicide in patients with depression in real-life conditions: A decision analysis model. Psychol. Med. 2008, 39, 1307–1315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barak, Y.; Olmer, A.; Aizenberg, D. Antidepressants Reduce the Risk of Suicide among Elderly Depressed Patients. Neuropsychopharmacology 2005, 31, 178–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mulsant, B.H.; Blumberger, D.M.; Ismail, Z.; Rabheru, K.; Rapoport, M.J. A Systematic Approach to Pharmacotherapy for Geriatric Major Depression. Clin. Geriatr. Med. 2014, 30, 517–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gonçalves, D.C.; Byrne, G.J. Interventions for generalized anxiety disorder in older adults: Systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Anxiety Disord. 2012, 26, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szanto, K.; Mulsant, B.H.; Houck, P.; Dew, M.A.; Reynolds, C.F. Occurrence and Course of Suicidality During Short-term Treatment of Late-Life Depression. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 2003, 60, 610–617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lapierre, S.; Dubé, M.; Bouffard, L.; Alain, M. Addressing Suicidal Ideations Through the Realization of Meaningful Personal Goals. Crisis 2007, 28, 16–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oyama, H.; Watanabe, N.; Ono, Y.; Sakashita, T.; Takenoshita, Y.; Taguchi, M.; Takizawa, T.; Miura, R.; Kumagai, K. Community-based suicide prevention through group activity for the elderly successfully reduced the high suicide rate for females. Psychiatry Clin. Neurosci. 2005, 59, 337–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fitzpatrick, A.L.; Powe, N.R.; Cooper, L.S.; Ives, D.G.; Robbins, J.A. Barriers to Health Care Access Among the Elderly and Who Perceives Them. Am. J. Public Health 2004, 94, 1788–1794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cochran, A.L.; McDonald, N.C.; Prunkl, L.; Vinella-Brusher, E.; Wang, J.; Oluyede, L.; Wolfe, M. Transportation barriers to care among frequent health care users during the COVID pandemic. BMC Public Health 2022, 22, 1783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, S.; Lee, K. Association between insurance type and suicide-related behavior among US adults: The impact of the Affordable Care Act. Psychiatry Res. 2024, 333, 115714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sall, J.; Brenner, L.; Bell, A.M.M.; Colston, M.J. Assessment and Management of Patients at Risk for Suicide: Synopsis of the 2019 U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs and U.S. Department of Defense Clinical Practice Guidelines. Ann. Intern. Med. 2019, 171, 343–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cray, H.V.; Pasciak, W.; Breheney, R.; Vahia, I.V. Public Awareness Campaigns on Suicide Prevention Are Not Optimized for Older Adults. Am. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry 2025, 33, 463–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ng, R.; Chow, T.Y.J. Aging Narratives Over 210 Years (1810–2019). J. Gerontol. Ser. B 2021, 76, 1799–1807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Risk Factor | Individual Interventions | IPT Construct |

|---|---|---|

| Sociodemographic & Financial Strain |

|

|

| Cognitive & Physical Health Issues |

|

|

| Psychiatric Conditions (e.g., Depression, Anxiety) |

|

|

| Psychological Determinants (Life satisfaction, Purpose in Life, Hopelessness, Resilience) |

|

|

| Risk Factor | Interpersonal Interventions | IPTS Construct |

|---|---|---|

| Loneliness & Social Isolation |

|

|

| Lack of Social Support |

|

|

| Caregiver Stress |

|

|

| Risk Factor | Organizational Interventions | IPTS Construct |

|---|---|---|

| Barriers to Mental Healthcare |

|

|

| Lack of Awareness & Training in healthcare |

|

|

| Access to Lethal Means (at the organizational level) |

|

|

| Financial safety net policies |

|

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Xian, S.; Ramanathan, S.; Glatt, S.J.; Ueda, M. Geriatric Suicide: Understanding Risk Factors and Prevention Strategies Using a Socioecological Model. J. Ageing Longev. 2025, 5, 40. https://doi.org/10.3390/jal5040040

Xian S, Ramanathan S, Glatt SJ, Ueda M. Geriatric Suicide: Understanding Risk Factors and Prevention Strategies Using a Socioecological Model. Journal of Ageing and Longevity. 2025; 5(4):40. https://doi.org/10.3390/jal5040040

Chicago/Turabian StyleXian, Sophia, Seethalakshmi Ramanathan, Stephen J. Glatt, and Michiko Ueda. 2025. "Geriatric Suicide: Understanding Risk Factors and Prevention Strategies Using a Socioecological Model" Journal of Ageing and Longevity 5, no. 4: 40. https://doi.org/10.3390/jal5040040

APA StyleXian, S., Ramanathan, S., Glatt, S. J., & Ueda, M. (2025). Geriatric Suicide: Understanding Risk Factors and Prevention Strategies Using a Socioecological Model. Journal of Ageing and Longevity, 5(4), 40. https://doi.org/10.3390/jal5040040