1. Introduction

Patan Durbar Square is one of Nepal’s most prominent heritage destinations and forms part of the Kathmandu Valley World Heritage Site (WHS), inscribed by UNESCO in 1979 [

1]. The area is broadly categorized into two zones: the monumental zone and the surrounding core residential zone. The monumental zone contains temples and palace structures with intricate Malla-era carvings (12th–17th century), while the residential zone showcases the evolution of Newar urban morphology and social organization [

2]. Patan, historically known as Lalitpur, flourished during the Malla period, which is widely recognized as Nepal’s golden era of architectural development [

2].

In 2006, a section of the traditional residential core was officially demarcated as the buffer zone of the Patan Monument Zone (PMZ) by Nepal’s Department of Archaeology (DOA), following UNESCO’s post-2005 requirement to delineate protective buffer zones for all World Heritage Sites [

3,

4]. The buffer zone concept, introduced through the 1972 World Heritage Convention and refined in the Operational Guidelines, is intended to protect the Outstanding Universal Value (OUV) of heritage sites from external threats such as urban encroachment and infrastructure development [

4]. Although these zones are not part of the core heritage site, they influence its integrity and are subject to regulatory oversight.

Despite these protective measures, the buffer zone of Patan has faced increased challenges from urbanization, modernization, migration, and tourism-related pressures, resulting in noticeable transformations in streetscapes, building materials, and traditional land use patterns [

4,

5]. Between 2003 and 2007, these pressures led to the Kathmandu Valley WHS being placed on UNESCO’s List of World Heritage in Danger [

6]. In response, Nepalese authorities began formulating and enforcing conservation regulations, including height restrictions, façade controls, and reconstruction bylaws [

7]. However, enforcement remains inconsistent, and modifications, often in the form of façade mimicry without material authenticity, continue to accelerate.

Global and South Asian studies on heritage zones such as in Bhaktapur (Nepal), Jaipur (India), and Porto (Portugal) have emphasized the challenges of balancing cultural preservation with socio-economic modernization [

8,

9,

10]. Scholars such as Orbasli, Sengupta, and Bajracharya stress the need for integrated approaches that consider not only physical conservation but also community needs, tourism pressures, and economic transitions. Yet relatively few empirical studies have examined how residential buildings in active buffer zones, especially those still occupied by native populations, evolve in function and form while preserving intangible heritage values.

Several scholars have examined the challenges of heritage conservation in living urban settings, particularly within designated buffer zones. Studies in Bhaktapur and Kathmandu have highlighted how weak enforcement of conservation policies and the influence of tourism have led to superficial façade preservation without material or spatial authenticity [

5,

6]. The international literature, such as that produced by Orbasli and Gusman et al., emphasizes the tension between development needs and heritage protection in historic cores, often resulting in gentrification or the loss of resident communities. However, most research either focuses on monumental architecture or abstract conservation theory, with limited attention to how residential buildings evolve in actively inhabited buffer zones. This study addresses that gap by focusing on the spatial and functional transformation of traditional homes in the Nagbahal neighborhood, offering a grounded perspective from a still-living, culturally active settlement. Known for its historic Golden Temple (Hiranyavarna Mahavihar), ritual continuity, and social networks such as the Kwabaha Sangh, Nagbahal retains a high proportion of native residents and traditional festivals. This makes it an ideal micro-context for studying the dynamics of residential building transformation and cultural resilience within a protected urban fabric.

The research adopts a mixed-methods approach, incorporating architectural analysis, typological mapping, and semi-structured interviews to explore how residential buildings have changed in response to social, economic, institutional, and environmental factors. The temporal framework divides the study into four key phasespre-danger listing, danger zone period, post-removal from the list, and post-earthquake reconstruction (1979–2023), aligning historical changes with policy interventions.

In doing so, the study contributes to international discourses on living heritage, sustainable conservation, and community-based planning, offering empirical insights that reflect both top-down regulatory pressures and bottom-up cultural agency [

7,

8,

11]. The study further aligns with the sustainability framework promoted by the International Centre for the Study of the Preservation and Restoration of Cultural Property (ICCROM), which emphasizes the interdependence of cultural, social, environmental, and economic factors in safeguarding living heritage [

11,

12].

This study aims to investigate the transformation of traditional residential buildings within the buffer zone of the Patan World Heritage Site, focusing on the Nagbahal neighborhood. It seeks to identify patterns of functional and spatial change, examine the socio-cultural and regulatory factors driving these transformations, and evaluate their implications for heritage conservation. By analyzing both physical modifications and evolving occupancy patterns, the research intends to develop context-sensitive strategies that balance urban growth with the preservation of architectural and cultural values.

2. Materials and Methods

To investigate the spatial and functional transformation of residential buildings in the Nagbahal neighborhood, a typology-based purposive sampling method was employed. This sampling strategy was selected due to the highly contextual and heterogeneous nature of the built environment within the heritage buffer zone, where each building type embodies distinct historical, architectural, and functional characteristics.

Figure 1 illustrates the complete methodology of the research, which is explained in detail below.

Purposive sampling was used rather than random sampling, as is common in heritage and urban studies, where the goal is not statistical generalization, but to capture architectural and functional complexity across typologically diverse buildings. This approach enabled the informed selection of cases most relevant to the study’s objectives.

To understand how residential buildings have evolved, the research design included a time-phased analytical framework that divides the study period into four key historical and socio-political phases. These phases correspond to critical shifts in heritage policy, urban development, and socio-economic behavior in the Kathmandu Valley, particularly concerning the Patan World Heritage Site.

To facilitate temporal analysis, the study timeline was divided into four distinct phases.

Phase 1: 1979–2002 (before inclusion in the UNESCO danger list). This period marks the time from Patan’s inscription on the UNESCO World Heritage List (1979) up to the point when the site was flagged for potential delisting due to encroaching development threats. Buildings during this time were largely intact in their traditional form, and the pace of transformation was gradual. However, early signs of modernization, such as minor structural modifications and internal functional changes, began to emerge in response to changing lifestyle needs.

Phase 2: 2003–2007 (UNESCO danger zone period). This phase represents a significant turning point when the Kathmandu Valley World Heritage Site, including Patan, was officially placed on UNESCO’s Danger List due to uncontrolled urban development and loss of authenticity in buffer zones. In response, government authorities began formulating and enforcing design guidelines, such as height restrictions and façade controls. This period saw accelerated transformation, as many property owners rushed to rebuild or modify structures under ambiguous or weakly enforced conservation regulations.

Phase 3: 2008–2015 (Post-danger zone period to pre-earthquake period). Following the removal of the site from the Danger List, conservation guidelines became more formalized. Yet building transformations continued—often in hybrid forms that attempted to balance compliance with traditional esthetics and the growing demand for modern amenities. This period is also characterized by increased commercialization, particularly on the ground floors of residences. Although external façades were often maintained or reconstructed in a heritage style, internal layouts and building materials underwent substantial modernization.

Phase 4: 2016–2023 (post-earthquake recovery period). The 2015 Gorkha Earthquake significantly influenced rebuilding practices across the valley, including Nagbahal. In this period, residents increasingly adopted RCC construction for perceived structural safety. At the same time, economic motivations led to further functional transformation—residences were adapted for mixed-use purposes, including homestays, cafés, and small businesses. The effect of tourism, modern housing demand, and policy-driven façade replication intensified during this time, often at the cost of material authenticity and spatial identity.

3. Case Study

Nagbahal is a small cluster located within the buffer zone of the Patan monumental area that can be seen in

Figure 2 below, playing a vital role in promoting tourism. This neighborhood has been a socio-culturally important settlement since ancient times, known for its historical and economic significance. According to interviews with residents, many of the ancestors in Nagbahal were involved in the silver handicraft trade with Tibet, a practice that has shaped the community’s economic strength. Details can be seen in

Appendix A. Even today, many more residents continue their traditional handicraft work, maintaining it as their primary source of livelihood and contributing to the local economy. This continuity of craftsmanship not only preserves their cultural heritage but also supports the tourism-driven economy of the area.

Nagbahal neighborhood is well-known for the Golden Temple, a sacred temple featuring a gold-plated roof and rich in artifacts and traditional rituals. The temple is located in a courtyard known as Kwabahal (Hiranyavarna Mahavihar, Sanskrit name), and the surrounding area is known as the Nagbahal neighborhood. The neighborhood features lots of courtyards and alleys, and Kwabaha is one of them. A significant portion of the population (over 80%) is affiliated with a single association known as the “Kwabaha Sangh”. Kwabaha is uniquely designated for religious functions and contains no residential buildings. All male residents, from their childhood, are required to join this association and strictly adhere to its rules. Those who fail to obey may lose their membership and the members who lose their membership cannot participate in any religious and ritual functions, and they cannot even enter the temple’s Deity room. As a result, most residents are cautious about breaking the rules.

Similar socio-cultural and urban heritage dynamics have been documented in historic buffer zones of other cities, such as the Islamic Cairo quarter in Egypt, the historic center of Porto in Portugal, and the Pink City of Jaipur in India. These cases, like Nagbahal, reflect the pressures of modernization, tourism, and regulatory challenges while offering varied strategies for sustaining cultural and architectural continuity [

8,

9,

10]. Such parallels strengthen the relevance of Nagbahal as a living heritage site within a global urban conservation discourse.

Once a year, the association holds a mandatory feast for all members. The members who are unable to attend have to pay a financial penalty. This is the most anticipated event where each member has the opportunity to connect and share updates on their business and community development. For this reason, people who have moved to new settlements away from their traditional neighborhood feel excitement and enjoy the annual feast. During this event, new development plans for the year are announced. Another important social group in the neighborhood is “Aaju Guthi”, comprising the 30 eldest members. They have to take responsibility for performing religious rituals on behalf of the association, and also they have to do the daily worship rituals of the gods and goddesses in the courtyard of the Golden Temple. Additionally, these 30 elderly individuals serve as the primary decision-makers for the organization.

Since more than half of the population is a member of a single organization, they are united in their approach to every neighborhood-related decision. While the association’s efforts to uphold cultural traditions, there is relatively limited focus on raising awareness about the broader heritage value among its members. The association continues to follow ritual practices rooted in ancestral customs, which present challenges when it comes to adapting to contemporary needs. As a result, cultural preservation has primarily occurred through rituals, feasts, and festivals, whereas the conservation of tangible heritage, particularly private traditional residential buildings, has received comparatively less attention. The association does not encourage native people to leave their native homes for new immigrants to rent. As a result, there are fewer homes for rent. The majority of people enjoy spending their free time in the courtyard with their friends. For this reason, the majority of people make daily or semi-weekly trips to the neighborhood squares. The majority of the aboriginal population has strong psychological ties to the deity of Kwabaha and has no desire to relocate to another community. Thus, the region continues to maintain its unique cultural and traditional continuity to this day. Their workplace culture is the other factor that unites them. The majority of the residents in this area are connected through handicraft businesses.

For economic development and building modern homes, native residents may unknowingly contribute to the degradation of heritage due to limited awareness about the heritage value. Most traditional heritage residential buildings are going to be demolished to make new RCC buildings, even though old buildings can stand for many more years if they are maintained properly. The second reason is due to the government rules and regulations in this area of reconstruction.

The local government has delegated the authority for overseeing construction and reconstruction activities in the area to the Department of Archaeology (DOA), which enforces specific regulations. All new buildings are required to be earthquake-resistant, a mandate that has indirectly led many residents to reconstruct using reinforced concrete (RCC). Additionally, buildings must feature brick façades with traditional wooden windows, and there are height restrictions in place—structures cannot exceed 36 feet, effectively limiting them to a maximum of four floors with modest floor heights. However, there is currently no financial support or grant mechanism available to assist residents in preserving or restoring heritage buildings in their original form. This may be because of the institutional weakness of the government to educate people about the value of heritage.

4. Results

4.1. Spatial and Functional Transformation of the Residential Building

The history of Patan and the Kathmandu Valley dates back to the Lichchhavi dynasty (3rd–8th century); however, no residential buildings from that period have survived. The oldest surviving residential structures date from the Malla period (12th–17th century) [

13,

14]. Since the Malla era, Newar communities have densely populated the historic city of Patan, characterized by courtyard-based urban planning and a network of narrow alleys and streets.

Figure 3 illustrates the building alignments along the street and within the courtyard of Nagbahal, where various building types can be observed. Courtyards of varying sizes are a key feature, serving as important spaces for daily social interactions and festival gatherings [

2].

Traditional residential buildings with Newa architecture are balanced by symmetry and hierarchy of the fenestration in the front façade and a defined purpose for each floor. Typically, these homes consist of four stories, each with a specific name and function like Chheli, Matan, Chota, and Baiga:. The traditional buildings have a load-bearing structure, made using wood and thick walls of brick in mud mortar, having a rectangular base [

15].

The ground floor, known as Chheli, is primarily used for handicraft workshops and storage of different materials that the owner requires, including agricultural equipment [

14]. The first floor, called Matan, is used as a bedroom and contains lattice windows on the front façade to see exterior views of the surroundings. The second floor, named Chota, is used as a family room. Newari people used to host large gatherings and feasts on different occasions as part of their culture. Due to the large number of guests on these occasions, the hosts would require large, spacious rooms to host the guests in. The Chota used to have small connecting doors to the attached houses. These doors would allow a larger space to entertain guests and would have the largest, most intricately carved window, offering views of street festivities. The topmost floor, called Baiga, is a highly private area used for cooking, dining, and worshiping, with no access granted to outsiders.

Figure 4a illustrates the vertical division and functional use of the building, while

Figure 4b presents the façade of a typical residential structure accoeding to Newa: architecture. The houses had sloped roofs and were covered with clay tiles [

14,

16].

The typical residential buildings in this region have undergone substantial changes over time for various reasons. This change has been mainly driven by globalization, which has forced homeowners to modify their homes to suit contemporary demands. Examples of these modifications include turning spaces into commercial spaces, rental properties, or lodging for perceived sustainability [

17]. These buildings have undergone structural alterations in addition to functional changes in response to evolving social and economic demands. The typical Newa architecture transitioned into Neoclassical during 1806–1951 A.D., but the use and materials remained the same. The decorative lattice windows were replaced by rectangular vertical windows in this period [

18]. It was widely implemented in the reconstruction of most residential buildings after the 1934 A.D. earthquake in Kathmandu. This is a major event that drove the urbanization of architecture in the core traditional city. The transformation of residential building façades from the Malla to the Shah and Rana periods is depicted in

Figure 5 below.

Figure 4.

(

a) Typical section of Newari residential building, retrieved from [

19]. Used under fair use for educational purposes. (

b) Typical courtyard view of Newari residential building, retrieved from [

20] and photographed by Pratik Rayamajhi. Used under fair use for educational purposes.

Figure 4.

(

a) Typical section of Newari residential building, retrieved from [

19]. Used under fair use for educational purposes. (

b) Typical courtyard view of Newari residential building, retrieved from [

20] and photographed by Pratik Rayamajhi. Used under fair use for educational purposes.

Figure 5.

Transformation of façade of residential building (Mall–Shah–Rana dynasty period). Retrieved from [

21]. Used under fair use for educational purposes.

Figure 5.

Transformation of façade of residential building (Mall–Shah–Rana dynasty period). Retrieved from [

21]. Used under fair use for educational purposes.

The development of cement concrete around 1990 A.D. developed the second shift in transformation seen in

Figure 6. The processes of concretization and globalization developed modern architecture in this area too, as all over the developing countries, and a significant number of RCC (reinforced concrete) structures were constructed. Due to the insertion of modern architecture and modern materials during the renovation and modification of old residences, the Newa architecture in the buffer area rapidly started to lose its traditional and historical significance. Therefore, the Kathmandu valley fell into the danger zone from 2003 to 2007 A.D. After the threat of losing the title of World Heritage Site, the government implemented bylaws that enforced the use of modern structures while maintaining a traditional façade. Even though the traditional building materials and technology were not conserved, the buildings were thought to be more stable and earthquake resistant while preserving some of the historical features such as the façades. It is due to this change that most of the houses today are rebuilt with concrete and cement with brick façades and vertical windows. Traditional Newari architecture and its usage were no longer suited to the modern lifestyle of today’s people. As a result, changes occurred not only in the materials used, but also in the building’s function. The use of residential buildings shifted to a mixed-use model, with part of the space used for living and part used for generating income through rentals or personal businesses.

But in recent time, buildings in this neighborhood can be categorized into five types based on construction materials, design patterns, and construction periods: very old buildings (typed A), old buildings (typed B), modern buildings (typed C), contemporary buildings (typed D), and ruined buildings (typed E) [

22], as shown in

Figure 5. Just two houses in this neighborhood were in ruined condition at the time of data collection.

In each type of building, functional change can be found. In ancient times, residential buildings in this area were constructed according to Newa architecture and used only for their residential purpose; but nowadays, the use is changing to fulfill new demands according to the shifting of time. In this neighborhood, at the time of data collection, only 20.45% of houses are using their space only for residential purposes, whereas 68.18% of houses have mixed use, and the remaining 11.37% of houses have been completely used for business purposes. The bar chart is presented in

Figure 7 and relevant data is provided in

Table 1.

4.2. Factors Influencing the Transformation of the Residential Building

The residential buildings have their defined purpose and use in previous times, but the traditional purpose has shifted significantly in the modern era. As there is no defined land use plan in the area, the owners have begun using the buildings for new purposes that are more profitable to them. Residential properties are being used for different purposes as time goes by, affecting the built value of the area. International studies on related cases indicate that the following are some of the reasons that are probably going to affect such a shift.

Culture is one of the main reasons for changing the use of space, creating territorial differentiation with one another. Language, art, built heritage, rituals, and traditions are just a few examples of the tangible and intangible elements that can be impacted by culture [

2,

22]. Not only limited to this, culture can be defined as social aspects, historical aspects, local people’s everyday lifestyles, the handicrafts sectors, and other traditional creative industries [

10]. Culture plays a vital role in shaping the significance and preservation of a place’s heritage. When cultural practices are embraced with a sense of joy and a thoughtful understanding of their historical or scientific foundations, they can contribute meaningfully to the conservation and appreciation of tangible heritage. However, if traditions are followed without reflection and are rooted in superstition, they may inadvertently contribute to the neglect or deterioration of that heritage. Therefore, a balanced and informed approach to cultural practices is essential for safeguarding heritage for future generations. Some important insights were gathered from interviews with different age groups, which helped to conduct a qualitative analysis of the intangible aspects of this area.

A 75-year-old man and his 68-year-old wife, who continue to reside in their ancestral home, shared their perspective:

“Our son and his family have moved to a new house due to parking issues, but we chose to stay behind. In a new neighborhood, we wouldn’t find the same sense of community that we have here. I was born and raised in this area—I know everyone, and I actively participate in community meetings. I can walk around freely, meet friends, and stay physically active, which contributes to my well-being. If I had moved with my son, I would likely feel confined and isolated indoors. During festivals, our entire family gathers here to celebrate. Although the house is small, everyone prefers coming here over the new home because of the vibrant social atmosphere and cherished traditions. My wife and I plan to stay here as long as we can manage on our own”.

A 52-year-old man who migrated out of the neighborhood shared his thoughts:

“I have a deep attachment to this settlement and hold it close to my heart. However, due to a family division, I had to move away. My younger brother’s family and our parents continue to live in our ancestral home. I often return to the neighborhood to spend quality time with old friends over tea and conversation. I also maintain professional ties here and visit for business-related discussions. During festivals, I usually come with my family to reunite with relatives and celebrate together. I particularly enjoy participating in traditional events such as Samvoye—the communal feast organized by the Kwabaha Sangh—and Samyak, a major puja held every four years by the Golden Temple”.

A 38-year-old woman shared her perspective:

“Although I was not born in this neighborhood, I deeply appreciate its vibrant culture and festivals. However, there are still a few traditional beliefs and practices that feel outdated in today’s context and can pose challenges, particularly for women’s personal and professional growth. I now live in a different community where I feel free from such constraints and do not judge based on traditional expectations, especially in my role as a daughter-in-law. As a working woman, I value my independence. That said, I still enjoy returning to participate in the festivals here, as the cultural richness of this place is truly special”.

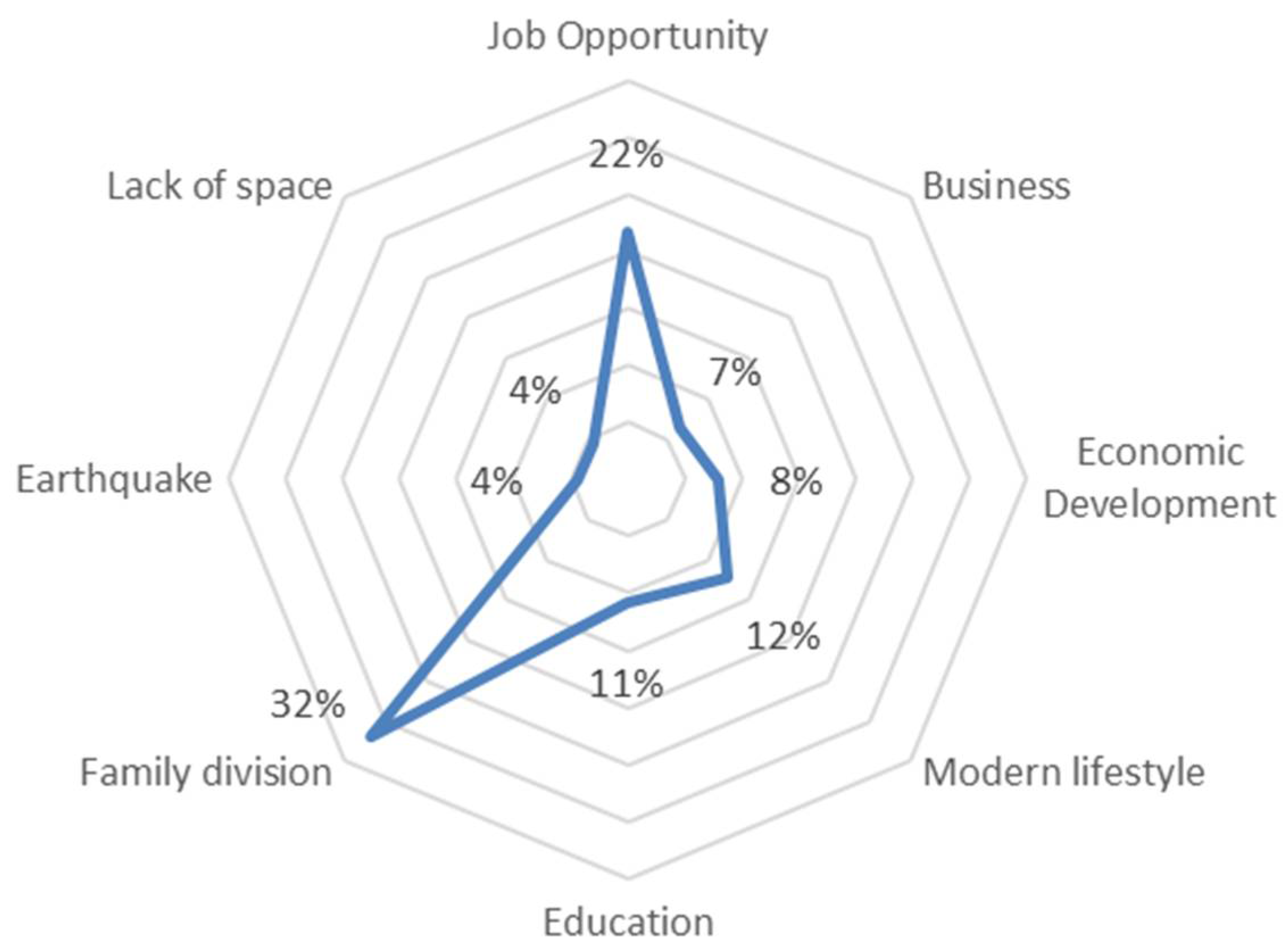

Based on all the interviews, it can be interpreted that culture plays a vital role in conserving the intangible heritage of this neighborhood, particularly through festivals and social functions. The key interpretations derived from the interviews are presented in

Figure 8.

Developing economic activities can increase the number of visitors and new residents in heritage areas [

2,

10]. Rehabilitation, reuse, and tourism-oriented shops, homestays, cafes, and eateries are some examples of economic activities that may increase the migration and flow of people in the area [

2,

9,

10]. In addition to economic activities, economic policies also serve as key factors influencing changes in the use or occupancy of buildings in any given area. The types of businesses that flourish or diminish within a particular location are often closely shaped by the local economic policies and regulatory frameworks implemented over time [

1]. Institutional weakness, implementation of policies, land use patterns, and immature policies may be the cause of change in the use of residential buildings [

2,

7]. Therefore, the enforcement of social or economic policies may be a key factor behind the change in occupancy within the buffer zone.

Although people are shifting their residential spaces for various economic development purposes, 88.63% of buildings still have native people residing in this neighborhood. Nowadays, 59.1% of buildings use their ground floors for economic purposes, such as cafés/restaurants, handicraft shops, groceries, pharmacies, and clothing shops, which are often run by residents or rented out. Most of the ground floors that are oriented to the road network are open as shops, drawing the interest of all visitors.

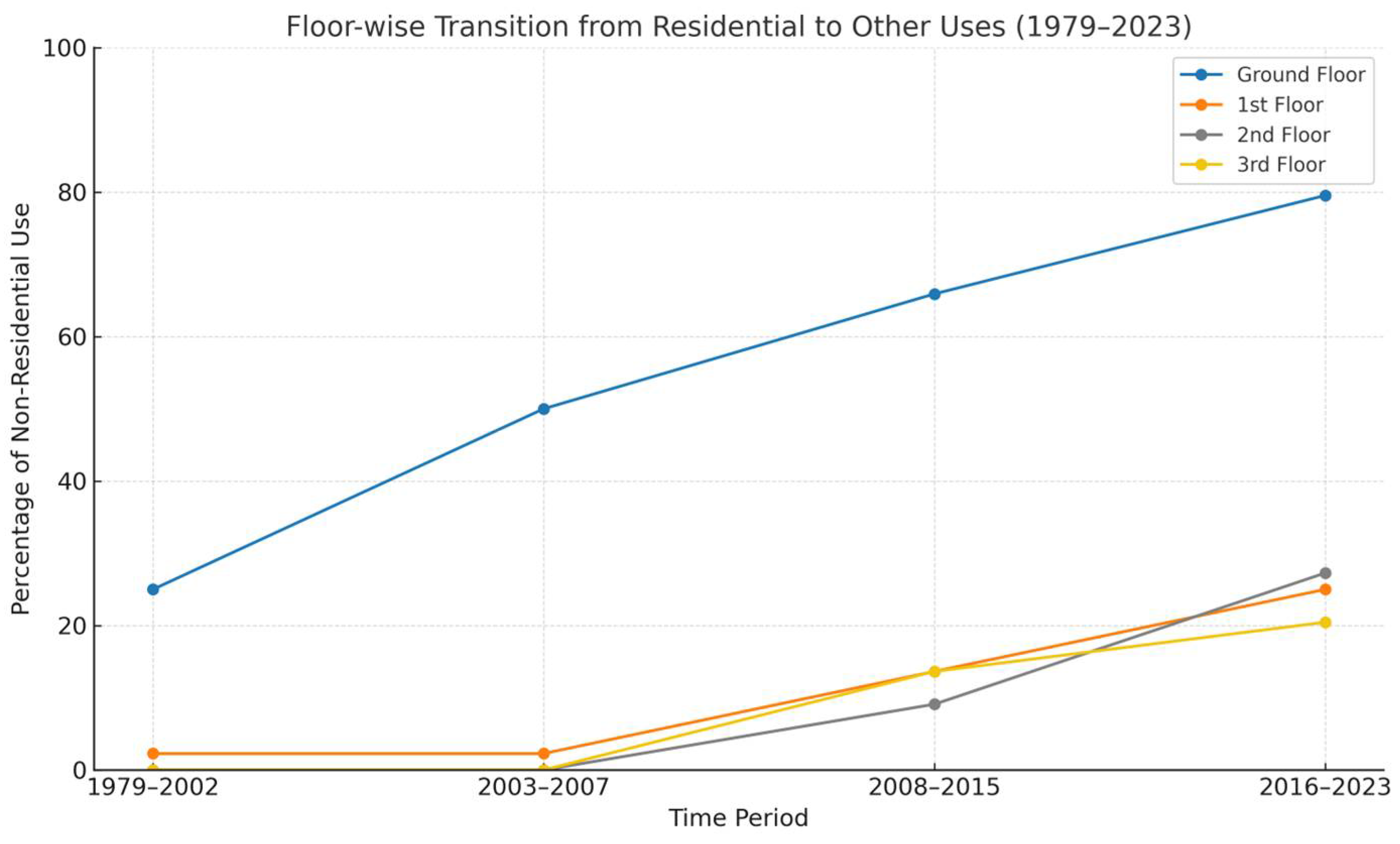

Figure 7 shows that the use of the ground floor has been increasingly shifting from residential to commercial purposes over time (from 25 to 79.54%). Similarly, most of the first, second, and third floors are used for bed and breakfasts, art galleries, and lodging facilities, which mostly attract tourists and young people. The chart shows that almost 25% of houses have changed their use, and it has been in an increasing pattern since 2007 A.D. This demonstrates how residential buildings are transforming their spaces into financial developments seen

Table 2.

Similarly,

Figure 9 clearly illustrates the transformation of residential buildings into various income-generating facilities, such as shops, bed and breakfasts, restaurants, and other tourist-oriented businesses. Some spaces have been converted into homestays and residential rentals, although at a relatively low rate. After 2007, this transformation accelerated and continued at a similar pace in the following years. The detailed transformation of ground floor functions is presented in

Figure 10 and relevant detail data is provided in

Table 3.

In addition to the factors mentioned above, contextual observations suggest that behavioral change in native residents is one of the prime reasons for change in the use of residential buildings in the area. This includes the growing need for modern facilities, the pursuit of job opportunities, natural disasters, and even inter-family disputes [

2]. In earlier generations, living in joint families within modest homes was a cherished way of life, reflecting values of togetherness and shared responsibilities. In the modern context, however, there has been a growing preference for nuclear family structures, often influenced by evolving lifestyles, individual aspirations, and urban living dynamics. The 2015 earthquake had a significant impact on both the structural landscape and patterns of occupancy, prompting a shift toward more resilient construction practices and changes in residential preferences.

A total of 32% of households have migrated out due to the family division. Similarly, 22% of households have family members who have migrated, primarily due to job opportunities. In contrast, only a small number of families (4%) have relocated due to the earthquake or the demands of a modern lifestyle. This indicates that, in this context, neither the earthquake nor modern lifestyle changes have played a significant role in the transformation of building use (

Figure 11).

In this context, residential buildings in this area, being a part of the buffer zone, must obtain permission from the Department of Archaeology (DOA) for reconstruction. However, the DOA checks only for façade maintenance, coverage, and height restriction regulations. Since there are no specific guidelines or standards for traditional materials and techniques towards earthquake safety, the government does not permit the reconstruction of buildings using traditional materials. As a result, all buildings undergoing reconstruction must be constructed with RCC and curtain façades, which have similar traditional looks that are strictly followed by all construction in this area. This trend is contributing to the decline in the heritage value of this area by replacing original heritage houses with new ones having a copied facade. Even though there are height limitations in the buffer area, many houses (51.2%) have illegal vertical extensions. The repetition of similar façade designs of residential buildings often leads to a monotonous style. This can create only partial solutions and encourages the cautious use of modern materials.

4.3. Sustainable Conservation of Historic Areas

Sustainable conservation of heritage areas is very important these days. Without sustainability, heritage cannot be conserved, and without conservation, there is no value in the sustainability of heritage areas. Conservation of heritage is the process of preserving the ancestors’ gift to future generations, and sustainability encourages people to conserve their heritage. According to the International Center for Conservation in Rome, the heritage area should be sustained environmentally, socially, and economically. For environmental sustainability, renewable energy should be used while conserving the heritage [

11]. Similarly, for social sustainability, a community should be well educated and aware of heritage conservation. For economic sustainability, policymakers should be aware of economic development without hampering heritage value and the environment. So, preserving tangible and intangible heritage for a long time without hampering its value can truly bring about sustainable conservation. It should not be a burden to local people or be represented as anti-development. It may follow today’s new technological advancements, like energy-efficient technology, without hampering heritage value and characteristics [

8,

17]. Nowadays, tourism is a tool of sustainable development of historic areas, but over-tourism can destroy the heritage value by misusing the cultural resources and displacing native residents from the area.

Recently, preserving and reusing historic structures has become a tool for long-term, sustainable economic growth [

9]. Any location’s primary source of economic growth is tourism, but if gentrification occurs and locals begin to leave the area, it may not be the best course of action for sustainable conservation [

8,

11]. The primary beneficiaries of conservation in a sustainable manner must be the local population. However, sustainable tourism can negatively affect heritage areas by altering their architectural significance and cultural meanings [

11]. The suitability of heritage is based on four pillars: cultural, environmental, social, and economic need [

12].

To prepare a good, sustainable conservation plan for a heritage area, it is essential to be aware of the demands and requirements of the native people who represent the area’s culture. Society is essential to the maintenance of culture because culture cannot exist without the active involvement of its constituents. To ensure the long-term preservation of culture, the community must be financially strong. Therefore, a sustainable plan should include the economic development of the society without harming the heritage environment of the area.

5. Discussion

This study contributes to the growing body of knowledge on sustainable urban heritage conservation by offering a detailed, time-phased analysis of the spatial and functional transformation of residential buildings within a UNESCO buffer zone in Patan, Nepal. Unlike previous studies that focus primarily on monumental heritage or abstract conservation principles, this research foregrounds the lived experience and agency of native residents in shaping transformation processes. In doing so, it offers a bottom-up perspective that is often absent in heritage policy discourse. As a result of the analysis and discussion, the interpretation is effectively visualized in

Figure 12.

The findings validate that cultural cohesion rooted in rituals, religious institutions (such as the Kwabaha Sangh), and traditional economic systems like handicrafts business continues to play a central role in sustaining the heritage environment. Interviews with multiple age groups confirm that intangible heritage practices remain strong and actively influence residents’ decision-making. This supports global scholarship suggesting that social and cultural sustainability are key pillars in conservation outcomes [

8,

12].

Furthermore, the study validates the correlation between building use and urban morphology through quantitative data collected over four decades. The consistent transformation from residential to mixed or commercial use, especially on ground floors, is not random but follows patterns linked to road access, tourism, and economic utility. The occupancy data, coupled with local narratives, reinforce the claim that heritage conservation must integrate adaptive reuse and modern functional needs, rather than relying solely on preservationist ideals.

A critical contribution of this paper lies in its proposed framework for evaluating sustainability across four dimensions—cultural, social, economic, and environmental—within a living heritage settlement. While cultural and social sustainability are relatively strong in Nagbahal, architectural and ecological sustainability are threatened by copied façades, illegal vertical extensions, and lack of material authenticity. This confirms gaps in current policy and institutional implementation, as echoed in similar buffer zone studies [

7,

9].

Compared to other South Asian heritage cities, such as Jaipur, India, and Bhaktapur, Nepal, the Nagbahal neighborhood stands out for its sustained native residency and strong community-based cultural continuity. In Jaipur, the historic urban core has undergone significant gentrification, with increasing commercialization, boutique conversions, and the displacement of traditional residents due to tourism-driven redevelopment [

9,

10]. Similarly, Bhaktapur has faced pressures of heritage commodification, where cultural spaces are often adapted to attract visitors rather than support local livelihoods, leading to a gradual erosion of authentic community life [

6,

14]. In contrast, Nagbahal has retained its indigenous population and social networks, with cultural practices such as rituals, feasts, and festivals continuing to shape daily life. Despite ongoing physical and functional transformations, this continuity contributes to a rare model of resilient heritage urbanism, where adaptation to modern needs occurs without undermining the community’s heritage identity.

For policymakers and conservation practitioners, this research provides validated, field-based evidence that heritage preservation in buffer zones can be effective only when it engages local knowledge, aligns with community needs, and supports socio-economic continuity. The methodological integration of architectural analysis, community interviews, and time-based occupancy mapping can be replicated in other historic settlements seeking sustainable conservation.

Although the 2015 earthquake did not cause significant structural damage in Nagbahal, it nonetheless catalyzed a reconsidering of building safety and functionality. More notably, the area has experienced a series of socio-economic transformations driven primarily by rising economic aspirations and intra-family property divisions. These factors have encouraged residents to modify or repurpose their buildings in ways that accommodate changing lifestyles, business opportunities, and household structures.

Despite these pressures, the neighborhood continues to exhibit a strong degree of social resilience. As of the time of study, 88.63% of buildings remained occupied by native residents—a figure that reflects both the enduring attachment of the community to place and the success of cultural and institutional mechanisms in maintaining neighborhood cohesion. This sustained presence of residents reinforces the cultural continuity of the area and offers a foundation for future conservation efforts rooted in community participation.

6. Conclusions

The Nagbahal neighborhood exemplifies how a historic urban settlement can adapt to modern needs while preserving its cultural and architectural heritage. Despite noticeable physical and functional transformations in residential buildings, the area maintains key elements of sustainable conservation, largely due to the continued presence of native residents and strong community traditions.

Cultural rituals, festivals, and the local handicraft economy have played a central role in sustaining intangible heritage and fostering social cohesion. However, several challenges remain—most notably the growing prevalence of reinforced concrete structures with imitative façades, unauthorized vertical extensions, and a lack of financial and institutional support for authentic preservation. These issues, coupled with limited public awareness about the broader heritage value, pose a significant threat to the area’s architectural authenticity and long-term conservation goals.

Sustainable conservation in such contexts requires an integrated and inclusive approach. Design control alone is insufficient. Instead, policies must encourage community participation, empower local institutions, and provide incentives for using traditional building materials and techniques that are both earthquake-resistant and culturally appropriate. Conservation strategies should balance heritage protection with evolving functional needs and socioeconomic realities.

The experience of Nagbahal aligns with international cases where balancing resident needs, tourism pressure, and heritage value is central to sustainable conservation. Comparative insights from Jaipur, Bhaktapur, and Porto show that the continuity of community identity is a critical factor in preventing the erosion of authenticity. As such, Nagbahal offers transferable lessons for heritage settlements facing similar pressures, particularly in integrating adaptive reuse with strong local governance and cultural continuity.

The Nagbahal case illustrates that historic neighborhoods can serve as living models of sustainable heritage urbanism when policy, culture, and community aspirations align. Supporting this alignment through further research, multi-level collaboration, and adaptive policy frameworks is crucial for preserving similar buffer zones across the South Asian region and beyond.

In addition to these conclusions, several recommendations are proposed for future analyses:

Material Authenticity: Assess traditional materials and techniques for seismic resilience to offer alternatives to RCC;

Social Trends: Analyze demographic shifts and intergenerational views on heritage to guide culturally sensitive policies;

Comparative Studies: Compare Nagbahal with other historic towns to identify effective conservation strategies;

Institutional Roles: Review governance mechanisms to improve coordination and policy implementation.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.S.B. and S.S.; methodology, S.S.B.; software, S.S.B.; validation, S.S.B., M.M.K., and A.R.B.; formal analysis, S.S.B.; investigation, S.S.B.; resources, S.S.B.; data curation, S.S.B.; writing—original draft preparation, S.S.B.; writing—review and editing, S.S.B.; visualization, S.S.B.; supervision, S.S. and M.M.K.; project administration, S.S.B. and M.M.K.; funding acquisition, M.M.K. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The APC was funded by [Norwegian University of Science and Technology, SAMAJ] grant number [994001105]. Information regarding the funder and the funding number should be provided.

Institutional Review Board Statement

At the time the research was conducted, and as of today, there is no formal Institutional Review Board (IRB) or national ethics approval mechanism in place in Nepal for architectural or urban studies involving non-sensitive human data. However, a formal endorsement letter from the Department of Architecture, Institute of Engineering, Tribhuvan University was provided to confirm the academic nature of the research and the ethical standards followed. Authors confirm that the study was conducted in accordance with the ethical principles of the Declaration of Helsinki (1975, revised in 2013), and remain committed to upholding the highest standards of research ethics.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

As this research is still underway and has not yet reached its final stages, the data collected thus far remains preliminary and is therefore not available for public release at this time. In order to uphold the highest standards of integrity and ensure the accuracy of the findings, it is important that the analysis be fully completed and carefully validated. Once this process is finalized, the data will be made accessible to all relevant stakeholders in an appropriate and transparent manner.

Acknowledgments

I would like to sincerely thank the residents of the Nagbahal neighborhood for their invaluable cooperation and willingness to share their experiences and perspectives, which greatly enriched the research. Gratitude is also extended to colleagues and peers whose thoughtful feedback and academic guidance contributed meaningfully to the development of this study. Thank you to everyone who has played a part in making this endeavor successful.

Conflicts of Interest

The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| UNESCO | United Nations Education, Scientific and cultural Organization |

| WHS | World Heritage Site |

| PMZ | Patan Monumental Zone |

| PWHS | Patan World Heritage Site |

| OUV | Outstanding Universal Value |

| RCC | Reinforced Cement Concrete |

| DOA | Department Of Archaeology |

Appendix A

Questionnaire for quantitative data collection| | Owner Name: | House No.: | Contact No.: | Street No.: |

| No. | Question | Indicator | Remarks |

| 1. | Are you resident of the house? | Yes/No | |

| 2. | If yes, native or newcomers? | Native/Non-native | If non-native, jump to the questions. 9 |

| 3. | Do your whole family reside in the home? | Yes/No | |

| 4. | State the family members who are currently residing in the home. | (none/Parents only/Parents with children/Grandparents, Parents with grandchildren)

(2/3–4/5–8/all) | |

| 5. | How many members are there in your family? | 4/5–8/8–12/more than 12 | |

| 6. | Why other remaining family members are not residing in this home? | Job/Business/Education/Modern lifestyle/lack of space/Earthquake/family division/Economic development | |

| 7. | When other remaining family members start to leave the home to reside? | | year/time |

| 8. | Which floor is occupied by your resident purpose? | Gr. Fl./1st Fl./2nd Fl./Top floor/all | After this, Jump to ques. 14. |

| 9. | Did u buy the house? | Yes/No | comes directly from 1 |

| 10. | When did you buy this home? | | year/time |

| 11. | Why did you buy this home? | Facility/Opportunity/Business/Good social environment/Culture/others | indicate if others |

| 12. | Which floor is occupied by your resident purpose? | Gr. Fl./1st Fl./2nd Fl./Top floor/all | |

| 13. | How many your family members are currently residing in the home? | (Parents only/Parents with children/Grandparents, Parents with grandchildren indicate if others) | |

| 14. | Is this home being used for any other purpose rather than owner’s resident? | Yes/No | |

| 15. | Building Stories | 2/3/4/more | |

| 16. | What is the use of ground floor of the house? | now | 10 yrs | 20 yrs | 30 yrs | 40 yrs | Resident in rent Handicraft Shop Handicraft Workshop Daily needs shop/Store Medical Others B&B/Restaurant Traditional Food Homestay

|

| | | | | |

| | | | | |

| | | | | |

| | | | | |

| | | | | |

| 17. | What is the use of first floor of the house? | now | 10 yrs | 20 yrs | 30 yrs | 40 yrs | Resident in rent Handicraft Shop Handicraft Workshop Daily needs shop/Store Medical Others B&B/Restaurant Traditional Food Homestay

|

| | | | | |

| | | | | |

| | | | | |

| | | | | |

| | | | | |

| 18. | What is the use of second floor of the house? | now | 10 yrs | 20 yrs | 30 yrs | 40 yrs | Resident in rent Handicraft Shop Handicraft Workshop Daily needs shop/Store Medical Others B&B/Restaurant Traditional Food Homestay

|

| | | | | |

| | | | | |

| | | | | |

| | | | | |

| | | | | |

| 19. | What is the use of third floor of the house? | now | 10 yrs | 20 yrs | 30 yrs | 40 yrs | Resident in rent Handicraft Shop Handicraft Workshop Daily needs shop/Store Medical Others B&B/Restaurant Traditional Food Homestay

|

| | | | | |

| | | | | |

| | | | | |

| | | | | |

| | | | | |

| 20. | In which group the house belongs to? | A/B/C/D/E | Old more than 100 Old more than 50 R.C.C. (open) R.C.C. (façade) New (old material)

|

| 21. | Is there any modification in the house? | Yes/No | |

| 22. | If yes, in which part modification takes places? | Openings Vertical expansion Vertical division Material Use Roof pattern

| |

| 23. | In which time frame, the modification takes place? | | Justify time year |

| 24. | Why the modification is needed in the house? | Structural defect lack of openings lack of area modern needs

| |

| 25. | If this house is reconstructed, which technology did it followed? | Modern load bearing frame structure traditional load bearing

| |

| 26. | If modern technology, why didn’t it follow old technology? | Govt. rules and regulation new technology is easy n durable old technology is not known by technician lacking of old material old technology is expensive

| |

| 27 | Orientation of House | Main road Public Courtyard Private courtyard Alley

| |

Questionnaire for Interview with Native People

Name

Contact No.

Age:

Are you a native resident of Nagbahal?

Are you/your whole family currently residing in your ancestor house?

Are you a member of Kwa Baha Sangh?

What is roll of Kwa Baha Sangh in the Nagbahal neighborhood?

How do you feel about the neighborhood?

Do you participate in social, cultural events in this neighborhood?

How would you describe your feelings or connection to the neighborhood?

Do you participate in social or cultural events held in Nagbahal?

If yes, which events are most important to you?

What function or event in Nagbahal do you think people value most and do not want to miss?

If you do not currently reside in your ancestral house, how often do you visit Nagbahal?

References

- Tiwari, P.S.R. Transforming Patan’s Cultural Heritage into Sustainable Future. Available online: http://www.kailashkut.com (accessed on 1 May 2016).

- Brinda Shrestha, R.C. The significance of Historic Urban Squares in Generating Contemporary City Identity: Case of Patan Durbar Square. In Revisiting Kathmandu Valley’s Public Realm: Some Insights into Understanding and Managing Its Public Spaces; Brinda Shrestha, R.C., Ed.; Nova Science: Melbourne, Germany, 2020; pp. 29–52. [Google Scholar]

- Minor Modifications to the Boundaries (Kathmandu Valley). 2006. Available online: https://www.informea.org/en/decision/minor-modifications-boundaries-kathmandu-valley (accessed on 1 July 2025).

- Martin, O.; Giovanna, P. World Heritage and Buffer Zones. In Proceedings of the Internation Expert Meeting on World Heritage and Buffer Zones, Davos, Switzerland, 11–14 March 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Chandani, K.C.; Alpana Sivam, S.K. Transformation of Traditional Vernacular Settlements: Lessons from the Kathmandu Valley. In Reframing the Vernacular: Politics Semiotics, and Representation; Springer Nature: Cham, Switzerland; Adelaide, Australia, 2020; pp. 261–271. [Google Scholar]

- Kosh Prasad Acharya, S.P. Establishment of the Kathmandu Valley. In Revisiting Kathmandu- Safeguarding Living Urban Heritage; UNESCO: Paris, France, 2015; pp. 139–144. [Google Scholar]

- Arthur Ebregt, P.D.G. Buffer Zones and Their Management: Policy and Best Practices for Terrestrial Ecosystems in Developing Countries; Volume 5 of Theme Studies Series; National Reference Centre for Nature Management: Gelderland, The Netherlands, 2000; ISSN 1568-2374. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, Y.; Salazar, N.B. Heritage and Tourism. In Global Heritage: A Reader; John Wiley &Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2015; pp. 240–254. [Google Scholar]

- Orbasli, A. Architectural Conservation; Principles and Practice; Wiley-Blackwell: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Gusman, I.; Chamusca, P.; Fernandes, J.; Pinto, J. Culture and Tourism in Porto City Centre: Conflicts and (Im)Possible Solutions. Sustainability 2019, 11, 5701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amarilla, B.; Conti, A. Built heritage and Sustainable Tourism: Conceptual, Economic and Social variablee. In Sustainable Development- Policy and Urban Development- Tourism, Life Science, Management and Environment; Research Gate: Buenos Aires, Argentina, 2012; pp. 147–171. [Google Scholar]

- Prabowo, B.N.; Salaj, A.T. Urban heritage and the four pillars of sustainability: Urban scale facility management in the World Heritage Sites. IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci. 2023, 1196, 012105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tiwari, S.R. The Ancient Settlement Of The Kathmandu Valley; Centre for Nepal and Asia Studies, Tribhuvan University: Kirtipur, Kathmandu, 2001; ISBN 99933-52-07-1. [Google Scholar]

- Sengupta, U.; Upadhyaya, V.B. Lost in Transition? Emerging Forms of Residential Architecture in Kathmandu. Elsevier 2016, 52, 94–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maskey, P.N. History and Construction System of Traditional Building in Kathmandu Valley; Ritsumeikan University, Tribhuvan University: Kyoto, Japan, 2012; pp. 6–8. [Google Scholar]

- Throsby, D. Economics and Capital; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK; New York, NY, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conservation, Sustainable and Conservation of the Historic Built Environment—An IHBC Position Statement; IHBC: 1 April 2020. Available online: https://ihbc.org.uk/toolbox/position_statement/sustainablilityconservation.html (accessed on 1 July 2025).

- Suwal, R.P. Vernacular Newar Dwelling-Its Construction Technologies and Vertical Functional Distributions. SCITECH Nepal 2021, 15, 58–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arun Saraf, N.A.A. Nepal Architecture Archive. 2024. Available online: https://thesaraffoundation.org/projects/nepal-architecture-archive/ (accessed on 1 July 2025).

- Gautam, S.; Republica. Preserving Our History; Republica, 2018; Available online: https://myrepublica.nagariknetwork.com (accessed on 1 July 2025).

- Korn, W. The Newari House. In The Traditional Architecture of the Kathmandu Valley; Kuloy, H.K., Ed.; scribd, 1998; Available online: https://archive.org/details/TraditionalArchitectureOfTheKathmanduValleyByWolfgangKorn_201712 (accessed on 1 July 2025).

- Sujata Shakya Bajracharya, S.S. Transformation of Residential Buildings of Patan World Heritage Site. In Proceedings of the 13th IOEGC, Dharan, Nepal, 6–7 April 2023; pp. 181–185. [Google Scholar]

| Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).