1. Introduction

For a discipline so old, architecture is surprisingly self-questioning about its own nature. Much ink has been spilled to defend specific views on its aims and processes. Often, these views result in open discussions on the very fundamentals of the discipline. In contemporary debate, for instance, many authors discuss the role of interactions in architectural design. However, there is little agreement on the subject. Some authors consider architecture an object-centered practice; others, a relational one. In the first case, architecture is about the objects it builds. In this perspective, buildings are considered autonomous entities; architectural interactions directly depend on their formal, technical, and aesthetic qualities. In the second case, architecture is understood to be about its interactions. In this view, design processes depend on complex relations between heterogeneous agents, architects among them. These relations also influence the possible success of an intervention.

In recent years, architectural interactions have become the center of many important reflections. Even so, they are not addressed with sufficient clarity. The discussion, as it is now, is quite ambiguous; a more precise understanding of the nature, typology, and scope of architectural interactions is lacking. Many authors discuss them as if they were equivalent or comparable. But they are not. Interactions between buildings and human agents, for example, are different from those with nonhumans. Nor are the interactions that a building establishes with people who work on its construction, and who live in it, the same. We aim to contribute to the debate by proposing a classification of architectural interactions, building on actor-network theory (ANT) [

1,

2,

3,

4,

5], object-oriented ontology (OOO) [

6,

7,

8,

9,

10], and Hodder’s theory of entanglement [

11,

12,

13]. In doing so, we do not intend to propose a comprehensive, or definitive, theory of architectural interactions. Our aim is to take the first step in the construction of such a theory, providing a starting point that could be expanded, improved, and built upon in future research. Through this classification, we intend to provide a theoretical tool that could help to better inform further discussion on the topic. We also intend to show how the opposition between buildings intended as autonomous objects or fields of relations is not as rigid as it is usually presented. In fact, autonomy and relationality seem to be rather complementary aspects.

This debate is quite relevant, as it describes a shift that is taking place in contemporary practice. Architectural objects have long entered a crisis [

14,

15], in the sense that there is little agreement on their intrinsic condition, identity, and purpose. This results in a multiplicity of positions on what architecture is about. In this sense, discussing interactions in architecture is something of potentially major consequences. Architects have always been driven, in their work, by ideas about architecture. This is indeed one of the roles of theory. A different insight into the relational–autonomous nature of buildings could open different futures for the discipline, while giving it new instruments to construct its present and judge its past.

In the context of this paper, the expression “architectural object” refers to any object conceived through physical and conceptual tools usually associated with architecture [

16,

17,

18]. A square, a piece of furniture, or a building can be an architectural object; so can a model. With the word “architecture” we refer to the discipline that is primarily concerned with the design, construction, and understanding of such objects, according to ethical, aesthetical, technical, functional, and sociocultural criteria [

19,

20,

21,

22,

23]. The word “building” is used instead to refer to any physical object designed for human habitation or activity, or to house symbolic–cultural functions related to individual or social life [

24]. By defining buildings this way, we are consciously excluding aspects that could also be considered part of them, such as the continuous flow of information that, since the digital age, is an integral part of most buildings [

25,

26,

27]. We do so to situate our paper in the broader field of research on human–thing interactions and, from there, to begin to analyze human relations with a specific type of thing: buildings.

2. Literature Review

The fact that buildings interact (with a context, with people, with nonhumans) is central to various contemporary fields of study, both inside and outside architecture. From gender studies [

28,

29,

30] to sustainable design [

31,

32,

33] to the more recent field of human–building interaction (HBI) [

34,

35,

36], much research investigates the individual or social interactions between people and buildings [

37,

38]. However, only a minor part of contemporary research attempts to lay the foundations of a relational theory of architecture, answering basic questions such as: should buildings be conceptualized as relational entities or not (this is, as we shall see, a key point in the debate)? What role do interactions play in architectural processes and outcomes? What kind of interactions do buildings maintain, and with which actors? In this paper, we focus on this area of research.

Buildings are complex entities that can be conceptualized in many ways. As previously noted, in contemporary discussion buildings are conceived either as autonomous objects, whose interactions stem from their physical presence, or as relational, resulting from interactions between various actors and conditions. This is the theoretical background of most reflections on architectural interactions. Depending on the authors, the discussion has distinct characteristics. According to Allen (1997) [

39], considering buildings as objects, or as fields of relations, opens the way to two different approaches to architectural design. These approaches do not depend on specific times and places but coexist throughout history. In his view, classical Western architecture conceived of buildings as objects. This implied designing them according to an idea of beauty as a closed formal system. By this understanding, once a building is finished, nothing can be added or removed without affecting the whole system. Buildings are designed from the outside in; formal logic strictly regulates their shape. In his essay, Allen discusses the Mosque of Córdoba as an example of the other approach. The Mosque is an open system, whose logic depends on the relations between its inner elements. The columns, with their distance, spacing, and alignments, give the building a flexible formal pattern, open to modifications. As such, the Mosque could be expanded—as indeed occurred more than once in the course of history—without its formal system being substantially modified. In his essay, Allen considers just a small part of architectural interactions. He addresses formal relations, between elements and parts of a building, but not the interactions between a building and a sociocultural context.

Kengo Kuma [

40] proposed a different take on architectural interactions, discussing the way buildings relate to their surroundings. Like Allen, Kuma distinguished between buildings as autonomous entities—which he calls “objects”—or relational—“anti-objects”. The main difference between these approaches lies in the degree of connection between buildings and surroundings. Objects are deliberately disconnected from them, whereas anti-objects blend in. According to Kuma, the first approach is inherent to most Western architecture, especially the Modern Movement. An exception in this sense is Bruno Taut, who “abhorred objects, believing architecture was more a matter of relationships” ([

40], p. 5). Kuma considers Villa Hyuga a good example of Taut’s sensibility; it is one of the two projects he built in Japan. The Villa is a very modest intervention, so gently placed on its site—a cliff facing the Pacific Ocean—that it is not possible to see it from a distance. One must stand in front of the Villa to appreciate it. Unlike Allen, Kuma addresses the interactions between buildings and surroundings. Like him, he prefers to focus on a specific aspect of the subject. He discusses how buildings relate to their physical context; not how they relate to people and society at large.

Recently, an interesting debate between ANT and OOO focused precisely on the role of interactions in design processes. The main point of disagreement between these positions is the degree of autonomy of buildings. According to ANT, the identity of buildings is largely shaped by the interactions between various human and nonhuman agents. The former includes architects, clients, contractors, communities, and all the people directly or indirectly involved in the construction of a building. The latter includes the physical, climatic, economic, and sociocultural conditions of a specific context. The interactions between these agents play a key role in the design of a building, its construction, and its lifetime.

ANT considers that object-centered understandings of architecture do not give due importance to the temporal dimension of buildings. By not properly accounting for interactions, they treat buildings as static entities, since interactions occur over time. This opinion is shared by various authors that seem close to ANT’s perspective [

41,

42,

43]. It is important to clarify that the time ANT refers to is a very different concept from time as understood in modern architecture. The latter described the process of moving in and out of a building to have a full experience of its spatial qualities [

44]. It was the personal time of people individually moving through the built territory. ANT time is instead a social time. It describes the interactions between all human and nonhuman actors involved in architectural processes. As such, it also describes the relationships between a building and its context, intended as a series of actors and conditions that develop over time.

In ANT’s view, the context includes clients, with their expectations and opinions about architecture; local regulations, with what they allow and what they do not; budget; local workforce, with the construction techniques they master and those they do not; contractors, with their intentions, which may or may not coincide with those of architects; economic juncture; the changing climate; and so on. In this sense, the identity of buildings is always a matter of negotiation with existing circumstances. ANT is particularly interested in the everyday context. Buildings not only participate in the everyday, they also construct it [

45]. They do so by providing a setting for bodies/space–time interactions [

46]. This setting is not neutral: the very characteristics of a building facilitate some kinds of spatial experiences and prevent others. In ANT’s view, buildings are relational because they create and result from a network of interactions but also because they encourage actors to interact in certain ways.

ANT investigates the role of interactions at all scales and phases of architectural design. However, it does not differentiate between types of interactions, nor does it elaborate on their nature. It mostly explains such interactions through examples. These examples, useful for understanding the extent of architectural interactions, nevertheless address them as if they were equivalent—which they are not. OOO does not deny the existence of all these interactions. However, it considers that buildings cannot be reduced to the sum of their relationships. They have an autonomous presence, not directly dependent on their interactions with surrounding places, people, and conditions. Reducing them to their interactions is a way of both undermining and overmining their identity [

6,

9]. According to OOO, ANT’s view, with its emphasis on interactions, might underestimate or even ignore the autonomous qualities of buildings. As a building is not the sum of its interactions, neither can its value be reduced to that of its interactions, however positive they may be. A building may have a positive relationship with its surroundings, for example, by being a sustainable construction, respectful of the environment; however, for OOO, this would say nothing about its architectural qualities, which may or may not be remarkable.

The role of autonomous and relational qualities is a major point of contention between both views. Autonomous qualities of a building, such as aesthetical and formal qualities, describe how it is per se, more than how it interacts with a context. Relational qualities describe instead how a building relates to its spatio-temporal surroundings. OOO defends the centrality of the former, while ANT—though never using the expression “relational qualities”—defends the centrality of the latter. In one case, the quality of an intervention resides mostly in its intrinsic, inner qualities; in the other, in the quality of its relations.

3. Discussion

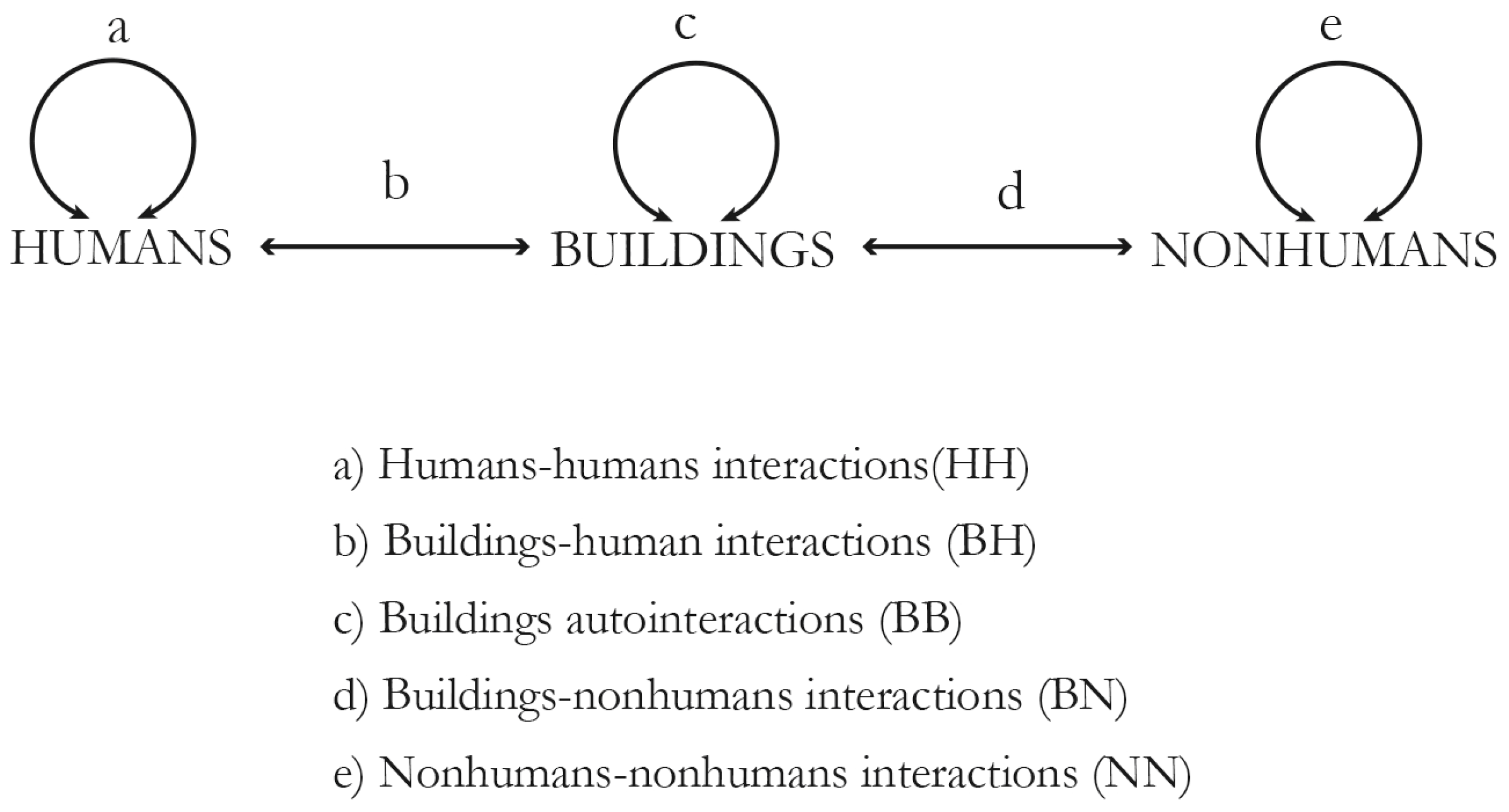

In this paper, we rely on an interpretive qualitative methodology to propose a classification of architectural interactions (

Figure 1). The argument is built on an interdisciplinary approach based on the interpretation of existing literature. Drawing on relevant research on the topic, we formulate hypotheses and objectives to be discussed in the main body of the paper. So far, there has not been enough in-depth research on the kinds of interactions that buildings can maintain; the nature of architectural relationships thus remains ambiguous. Object-centered understandings do not provide such insight, being focused on architecture beyond relationality. Relational understandings do so only partially, as they tend to focus only on some interactions and exclude others. By classifying architectural interactions, the debate could gain clarity. This could be a first step in recognizing the differences—in typology, intensity, and characteristics—between such interactions. Another ambiguous aspect of the debate is the radical opposition between autonomy and relationality. Indeed, the contraposition between buildings as autonomous objects, or as fields of relations, is one of the most widespread myths of contemporary discourse. In this sense, we consider that a careful assessment of architectural relations could help break this apparent contradiction, revealing autonomy and relationality as complementary aspects.

To construct our classification, we build on Hodder’s (2011, 2012, 2016) [

11,

12,

13] entanglement theory. Hodder argues that the history of culture is, to some extent, the history of interactions between humans and things. To elaborate, he distinguishes four pairs of interactions: things interact with things (TT interactions) and with humans (TH interactions); similarly, humans interact with each other (HH interactions) and with things (HT interactions). Hodder refers to these interactions as “entanglement”. Things have an agency; they are not inert. The way they relate to each other and to humans profoundly influenced how societies have evolved and how they live today. Through his proposal, Hodder aims to overcome the limits of anthropocentric conceptions of relations (focusing mostly on human–human interactions) and new materialistic ones (focusing mostly on the human–thing couple).

Buildings are a specific kind of thing, but this is not the main reason why we consider Hodder’s theory a valid starting point for constructing a classification of architectural interactions. The most important reasons are the following: although the theory deals in general with interactions between things and humans, it is easy to adapt in architectural terms; it has the merit of encompassing a wide range of complex reflections and insights in a conceptual structure of a simple but rigorous form; it is already part of the debate investigated by our research, being cited by Harman ([

6], pp. 36–39) in a paper on the autonomy and relationality of buildings (which also demonstrates how this theory is suitable for reflections on architecture). To adapt this classification to architectural discourse, we do not focus on the human–thing pair, but on the human–nonhuman distinction, as proposed in ANT [

47,

48].

The human–nonhuman distinction presents some problems. One is that splitting the world in this way suggests a somewhat anthropocentric symmetry, that is, a human-centered view of the cosmos. The second is that the expression “nonhuman” implies a wide number of heterogeneous actors, agents, and conditions [

49,

50,

51]. Even so, we find this distinction useful for our purposes. Although this distinction may be regarded as anthropocentric, it nevertheless recognizes the importance of nonhumans in architectural processes and outcomes. This would not have been the case had we relied on the human–thing pair.

In the next sections, we will therefore discuss the following relationships: humans–humans, as mediated by buildings (HH interactions); buildings–humans (BH interactions: a specific kind of NH interaction, since buildings are nonhuman agents); buildings–nonhumans (BN interactions); nonhumans–nonhumans (NN interactions); and finally, the internal relations that a building maintains with itself and its parts (a different type of interaction between nonhumans). This is intended as an open, fluid classification. Categories may overlap. Some interactions may belong to more than one category; also, in each phase of a building’s life, different types of interactions constantly intertwine.

Through our classification, we propose to investigate the following hypotheses:

- (1).

Existing nonarchitectural theories of interactions (such as ANT, OOO, or Hodder’s entanglement theory) can be translated into architectural terms.

- (2).

The relational nature of buildings can be better understood on the basis of established theories from other disciplines.

- (3).

The opposition between autonomy and relationality of buildings may not be as rigid as it is usually presented.

From these hypotheses, we aim to:

- (1).

Take the first step in the construction of an architectural theory of interactions. Our proposal is not intended to be a comprehensive or definitive theory, but a starting point that can be expanded, improved, and built upon in future research.

- (2).

Adapt existing reflections to architectural theory, by proposing a classification of architectural interactions.

- (3).

Explore the possibilities and limits of ANT and OOO when applied to architectural theory.

3.1. Human Agents–Human Agents (HH)

According to ANT, a building always results from the interactions between heterogeneous individuals, each with their baggage of ideas, objectives, skills, and perspectives (

Figure 2). Buildings are not a direct emanation of their architects. Clients, workers, architects, engineers, contractors, local community, authorities, constructors, stakeholders… Each of them pushes the project in different directions; each of them plays a role in the outcome. Architecture is a collective work; building is a social process. The 20th-century idea of the architect as a demiurge, who single-handedly could construct everything, “from the spoon to the city”, was inadequate to describe the reality of architectural work at the time, and it is even less so now [

52]. The clients, with their views and budget, play a key role in driving the project: they do so from the very first decisions, such as the choice of the architect. On the other hand, architects drive the project in directions that fit their interpretation of program and site. Sometimes local communities step in on an issue they care about: they do not want a building to be demolished, or a public garden to be replaced; and so on [

53,

54].

Not all actors play an equally important part, of course. Architects or clients play a more decisive role in shaping a building than, say, the supplier of concrete or timber shuttering; but architectural processes are indeed relational [

55]. However, buildings are not the unprocessed result of existing conditions. Circumstances strongly drive the project at virtually every stage, facilitating some outcomes and complicating others. Even so, an intervention can sometimes achieve a result that, in its place and time, would seem unlikely. Architecture can defy circumstances. In some cases, it can even change them, by opening up previously unsuspected possibilities. This is the case with many monuments built throughout history. The Eiffel Tower in Paris, for example, at the time of its construction was unusually tall, relied on an unusual technique, and adopted an unusual architectural language, which was initially quite unpopular [

56]. Nevertheless, it was built and played a pivotal role in changing the public perception of iron buildings. By doing so, it paved the way for much later architecture.

HH interactions concern not only people involved in the design and construction of a building but also those who inhabit it. There are several ways to inhabit a building: by living or working in it or by using it occasionally. As humans, we are a highly interior species; according to Klepeis et al. [

57], we spend almost 90% of our time in interior spaces. Most of our life is mediated by buildings, as are most of our interactions with other humans. Social interactions and daily rituals, when occurring inside buildings, are, in fact, a part of them. There is a connection between the architecture of a space and the events that occur in it [

58]. HH interactions change human agents, by creating social bonds. But they also change buildings, by affecting the way they are used and collectively perceived. It is also through HH interactions that buildings end up acquiring value for a community, which will ultimately decide how to use them and whether to preserve them over time. People are not an external addiction to a building; they are an integral part. Buildings are usually designed with the human factor in mind, considering how people could move, interact, use spaces, and react to their qualities. Usually, but not always: the infamous bedroom in Eisenman’s House VI, with a window splitting a couple’s bed in two for a purely formal reason, is a well-known example of autonomy-fetishism, where people, everyday life, and interactions are subjugated to the abstract logics of the architectural object ([

41], p. 22). People play a fundamental role in shaping the identity of a building, based on how they live in it. It may be interesting, in this sense, to recall the case of the Torre David in Caracas, which recently has been the subject of numerous investigations. In 1994, due to an economic crisis, the financial center Confinanzas Tower—later known as Torre David—remained unfinished and unused. Some years later, a community of homeless people occupied it and gradually modified its spaces to adapt it to a residential function [

59]. However, the most important transformation of the building was probably not in its physical structure but in how it was collectively perceived. For some critics, such as Hancox [

60], it went from being an incomplete symbol of modernity to an unpleasant vertical slum; for others, such as McGuirk [

61], it went from being a symbol of financial power to a remarkable example of participatory architecture. In both cases, through human interactions, the building experienced a meaningful change.

3.2. Buildings–Human Agents (BH)

HH interactions describe how human interactions influence buildings. BH interactions describe instead how buildings affect the lives of communities and individuals (

Figure 3); they primarily concern the people who directly or indirectly inhabit a building. By “inhabit directly” we refer to those who live or work inside a building or use it occasionally. By “inhabit indirectly” we refer instead to those who may never enter a building but have a very close relationship with it. This could be the case of people seeing a building every day on their way to work, or from the windows of their houses, and so on. This is indeed a way to inhabit a building, though different from the former. Habit, and the logic of affection, mediate our interactions with the built territory [

62]: we inhabit not only our houses but all the places and buildings that are part of our daily experience of the world. The relationship between buildings and human agents is neither neutral nor without consequences [

63]. Buildings change people. They do so by shaping everyday landscapes and giving a physical, visible presence to the place we call home. By doing so, they transform it from an abstract concept to something our bodies can relate to. At the same time, buildings also contribute to the construction of ordinary life [

64]: they facilitate certain kinds of actions, rituals, and events; they prevent others. Individual and social lives happen through architecture. This is also true at the city scale, where several studies have investigated how the built environment fosters gender inequalities and social segregation [

65,

66]. There is a relationship between the dynamics of society and their places [

67].

Buildings can also interact with people who do not inhabit them, neither directly nor indirectly. They can do so by altering the social dynamics of a place: a street, a neighborhood, or even a city [

68]. People may not have a direct relationship with a building and yet see their life variously affected by it. Sometimes the construction of a building initiates a process of urban regeneration [

69,

70]; in other cases, it can foster dynamics such as gentrification, by triggering processes that ultimately replace a community with a wealthier one [

71,

72]. The radiating power of buildings—that is, their ability to directly impact the lives of individuals and communities—can extend beyond immediate surroundings. In some cases, it might also extend well beyond the moment of their construction. This is the case with monuments, whose influence can last for centuries, even millennia. Monuments change cities at two levels. They modify their physical, visible structure but also their very identity, by changing how citizens understand the history and legacy of an urban environment [

73,

74]. Some buildings have such a strong radiating power as to inspire people who have never experienced them. One might have never been in the presence of a building, and only have seen it in a journal, book, or video, and yet be strongly influenced by it. When designing a project, architects usually turn to other buildings as references. Some of them may be buildings they actually experienced; most of them usually are not. Architects are constantly affected, both in their design and in their understanding of architecture, by buildings they only see in pictures.

3.3. Buildings–Nonhuman Agents (BN)

Cities and buildings are and have always been more-than-human territories, constantly modified, in their physicality and meaning, by several nonhumans [

75,

76] (

Figure 4). Some of these already have a place in architectural discourse; some do not. For the sake of the discussion, we will divide nonhumans into three categories: nonhuman living beings (plants, nonhuman animals); nonhuman entities (objects); and nonhuman conditions, that is, conditions that, although related to human activities, still maintain an important degree of independence from them. Buildings, in this sense, are a specific kind of nonhuman entity. Nonhuman living beings may inhabit architectural spaces just like humans [

77]. Dogs, cats, birds, flowers, trees…many animals and plants may find shelter inside or in the proximity of buildings. In the Anthropocene, some of them are more likely to find a home inside buildings than outside [

78,

79,

80]. Every nonhuman maintains a certain type of relationship with the built territory. Pets have their own way of moving through it, depending on the species, size, and personality; plants do not move, but also relate to some characteristics of spaces, such as daylight and shadows; and so on. Buildings affect nonhumans; nonhumans affect buildings back, in their meaning and use.

Analyzing the interactions between nonhumans and buildings could open the way to a rethink of architectural spaces, considering these other ways of living in them as well [

81,

82].

Buildings also interact with elements of the urban environment and other buildings as well. The relevance of this interaction can hardly be downplayed; a significant part of the identity of neighborhoods and cities depends precisely on the way buildings interact with each other [

83,

84,

85,

86]. Every building initially generates a state of tension with its surroundings, because it alters previous conditions and the visual–physical characteristics of a place. Such tension can be more or less intense and be perceived as positive, negative, or mostly neutral. This depends on many factors. One is whether the building confirms existing spatial qualities or proposes new ones. Another is whether the building is a loud object, distinct in scale and architectural intentions from the others, or whether it blends in [

87,

88,

89].

Places are always defined by some material elements, such as buildings, and the immaterial but no less real network of interactions between them. Among nonhuman entities, interior objects occupy a special place. Objects can profoundly change the identity of an interior, by modifying its possible uses, atmosphere, or both [

90]. An empty room becomes a bedroom by placing a bed inside; or a study by placing a table with a chair, shelves, and some books. Traditional Japanese houses exploited this aspect of architecture. Most of their rooms used to be empty: they acquired a specific function only the moment someone placed some objects inside them—for example, a zabuton cushion and a low table [

91].

During their lifetime, buildings can interact with various nonhuman conditions; a particularly important one is climate. Buildings are usually designed to suit the specific weather of a place. In addition, increasingly often buildings are intended to have as minimal impact as possible on the changing climate; it is the case of net-zero energy or carbon buildings [

92,

93]. Weather conditions are also a factor determining how buildings age. A building erected in front of the sea is likely to age in a specific way, because of sunlight, salt, winds, and humidity; a building erected in the desert, or on a rainy mountaintop, will age differently. Daylight, which varies greatly according to season and location, also plays an important role in this sense. The amount of sunlight, its direction, and its intensity affect the way a building can be perceived, as well as its shadows and the brightness of its colors. The visual presence of buildings largely rests on their interaction with sunlight, whose changing conditions also affect their appearance over the day, the seasons, and the years.

3.4. Nonhuman Agents–Nonhuman Agents (NN)

Buildings are made by humans and, mostly, for humans. However, they are a theater of continuous interactions between nonhumans (

Figure 5). These interactions can be as heterogeneous as the actors involved [

94,

95]. Pets can be harmful to plants. Furniture can be comfortable for pets. Daylight can affect the furniture. And so on. Plants have reduced mobility and stand in a specific place. Nonetheless, they interact with daylight and water. Indeed, this interaction is so important as to be vital. They may also interact with pets and, occasionally, with some ephemeral inhabitants of buildings, as bugs. Most importantly, plants interact with objects: the pot, the watering can, and, if they are small, the furniture they are on.

Unlike plants, most pets can move freely around buildings; therefore, they relate to architectural spaces in ways that in many respects are similar to those of humans [

96]. They have favorite places; they use furniture for their comfort; they move around spaces according to the time of the day and the rituals to be performed. Pets with less mobility, such as turtles or fish, have a different relationship with buildings. However, they also relate to elements, such as daylight or water, and objects, such as the aquarium. Like humans, pets are directly affected, in their daily lives, by the opportunities and constraints presented by a building. A cat may enter a room only through a door or see outside only through a window; the placement of both doors and windows is a design decision.

Objects have an agency, and a very important one. The very idea of the agency of objects is one of the key points of ANT [

47,

97]. Their agency is quite evident in relation to humans. Objects can enable activities that would be much more complicated, or impossible, without them. Without windows, it would be more difficult to regulate the amount of daylight and ventilation inside a house. Without doors, it would not be possible to open or close an interior as desired. Objects provide the paths for everyday life to occur. However, the agency of objects is also evident in relation to other nonhuman agents. A pot provides a plant a place to inhabit. A shelf may provide a place for the pot, so that the plant can have all the necessary daylight. A cushion gives the dog a place to sleep; a sofa, a place to rest. Objects also interact between themselves. The key interacts with the door, which will not open if the key is wrong or broken. A similar relationship exists between the handle and the door. A paper by Latour (1988) [

98], for example, describes the complicated sociology behind the door-closer. But objects can interact between themselves in another, more subtle way. The identity of every interior partly depends on how its objects fit together [

99]. Each object has a presence and visual characteristics; these may or may not match those of other elements in a room. For interior architecture, the relational nature of objects is an important aspect. This is especially true in the design of spaces where objects are the real protagonists, such as museums [

100]. Architects such as Carlo Scarpa and Sverre Fehn emphasized how, in the design of their museums, they played a central role: for each object, the right placement had to be found, where it could maintain the most positive interaction with daylight, people, and other objects [

101,

102].

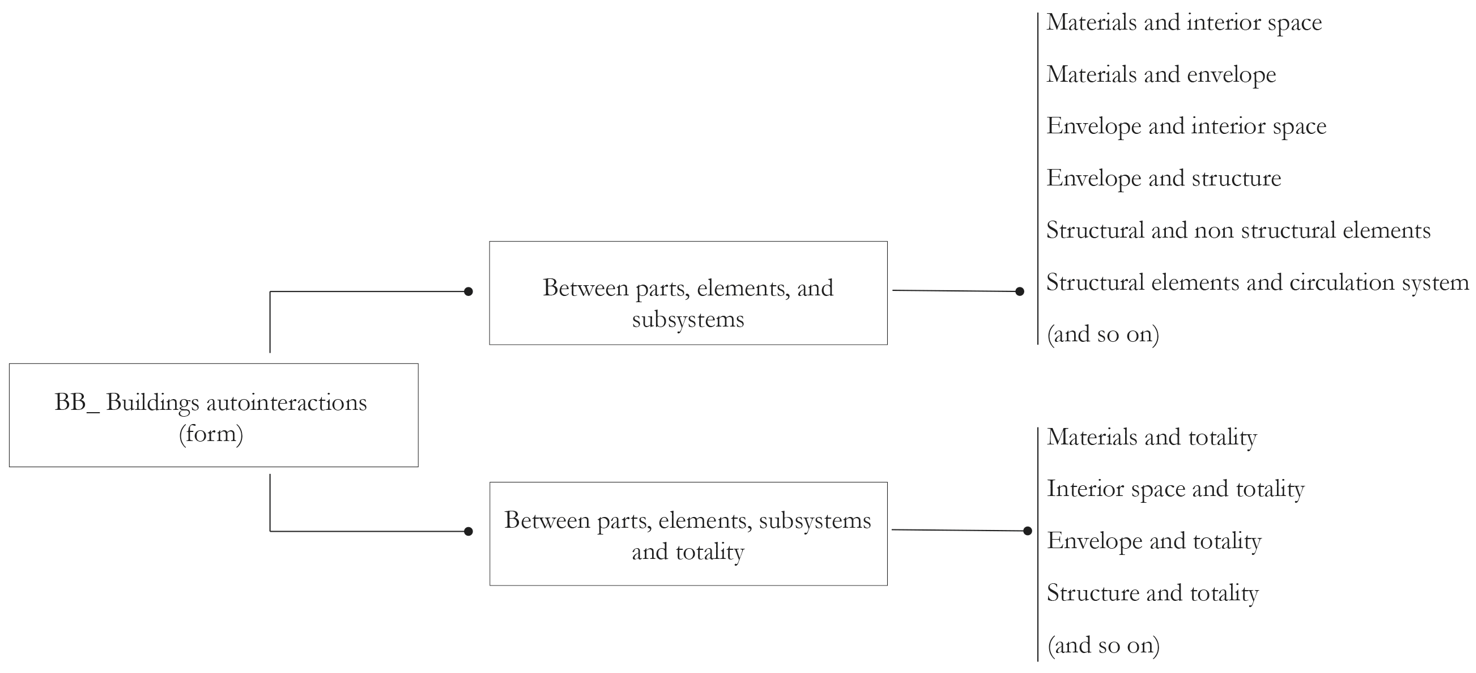

3.5. Building Autointeractions (BB)

Hodder’s taxonomy, with its four permutations of human–thing interactions, excludes an aspect that is particularly important in our discussion. This aspect is the autorelational nature of things, and among them, of buildings. Things also maintain complex relationships with themselves, and these relationships are of great importance in shaping their identity. This is especially true for artworks or products of creativity, such as buildings. Each building presents various internal relationships: between materials and spaces, served and serving spaces, envelope and interiors, envelope and structure, structural and nonstructural elements, etc. (

Figure 6) [

103,

104]. Indeed, buildings may be designed from a particular internal relationship. In recent decades, several projects have investigated the interaction between the envelope and the interior spaces. In some cases, this resulted in the design of structurally and formally autonomous envelopes, in others in continuity with the interior [

105]. As such, buildings have a somewhat ambiguous nature. They have a unity, that is, they can be conceptualized as individual pieces. At the same time, this unity might be understood, to some degree, as a by-product of the interaction between their parts, elements, and subsystems [

106,

107].

Usually, such internal relations go by the name of “form”. “Form” is a word that can mean different things; it might indicate the visual appearance of something, but also its internal logic, that is, the correspondences and interactions that structure something from within [

108] (Forty, 2004). The latter is the meaning we apply to the word “form” in this paper. According to Harman (2016) [

6], this is also how the word is mostly used in contemporary architectural theory, even by approaches often seen as opposites. This is the case, for instance, of Eisenman’s insights on form [

109] and Schumacher’s parametric architecture [

110,

111].

On various occasions, Eisenman (1970, 1984) [

112,

113] has argued for the intrinsic autonomy of architectural objects (Hays, 2009; Patin, 1993) [

114,

115]. He intends “form” as the internal essence of architecture, the logical arrangement of its parts, as well as a means of comprehensibility. However, he also clearly states that form is indeed relational (Eisenman, 2006) ([

109], p. 89) and depends on the interactions between elements and subsystems of a building. Schumacher ([

110], p. 204), in his reflections on parametric architecture, focuses on function rather than form and on some occasions directly contests Eisenman’s position precisely for this reason. But his take on form is also relational: parametric architecture understands the architectural object as a field of parametrically defined interactions between its internal elements. In the contemporary debate, the idea that buildings are autorelational entities is widely accepted [

116,

117,

118].

Even authors who consider buildings as autonomous entities, such as Eisenman and Schumacher, often understand their internal nature as relational, and see no contradiction in this. In fact, the autorelational nature of buildings not only does not contradict the idea of its autonomy but can be understood as the basis of such a claim. In its original meaning, the word “autonomy” identifies something regulated by internal, self-established rules [

119]. In this sense, buildings can be considered autonomous precisely because of the internal relations between elements and totality. Such interactions are different in every building, giving each one a unique presence and identity. The autonomy of buildings, in this sense, does not rest on their detachment from a sociocultural, physical context but on their formal congruence.

4. Conclusions

Buildings interact with several actors, under several conditions. In contemporary debate, this fact is widely recognized. However, there is little to no clarity in discussing architectural interactions, which are mostly treated as if they were equivalent. On the contrary, they are very heterogeneous. Classifying them should be a first step to better inform the discussion on the topic. Interactions between buildings and humans are different from those with nonhumans; these also differ from interactions between humans, or nonhumans, as fostered by architecture and also from building autointeractions.

The lack of a solid theory of architectural interactions can be made up for by contributions from other fields of study. Disciplines such as sociology or philosophy, among others, have suggested insights that can easily be translated into architectural terms. Theories such as ANT, OOO, or Hodder’s entanglement explore, in different ways, the very nature of objects and their interactions. With a small shift from objects in general to a specific type of object—the building—many of these reflections help to better understand architectural processes.

In fact, the relational nature of buildings can be better understood by hybridizing suggestions from within and outside the field of architecture. Intrinsically, architectural issues may on occasion be dealt with first and best by other disciplines. The relational nature of objects and, among them, buildings, seems to be one such case.

Architecture is usually considered either an object-centered practice or a relational one. As a consequence, buildings are considered either autonomous or relational: in their inner nature, in the process of design and construction, and in their interaction with a context. This is particularly evident in the debate between actor-network theory and object-oriented ontology. Theories such as OOO consider that buildings cannot be reduced to the sum of their interactions and focus on their autonomous qualities. Theories such as ANT consider that architecture is indeed about its relations and there is no possible autonomy for its objects. However, a closer look at architectural interactions reveals that autonomy and relationality are not opposing alternatives. They rather seem to be complementary aspects, which always coexist.

If by the word “autonomy” we mean something regulated by internal, self-established rules, buildings are autonomous because of the relational nature of form. Form is relational because it depends on, and takes its identity from, the interactions between parts, elements, and subsystems. This is how Eisenman and Schumacher, who defend the autonomy of the architectural object, also conceive its inner nature. If by the word “autonomy” we instead mean something that has a certain degree of independence from its surroundings, buildings are autonomous because each one establishes peculiar and unique interactions with its context.

Conversely, the relationality of buildings depends, to some extent, on their objectual and autonomous qualities. The fact that a building is what it is—with its presence, materiality, and aesthetics—is an important reason why it maintains some specific interactions with the surrounding conditions, agents, and actors. How a building interacts depends on how it is per se; neither does its autonomous presence conflict with its relationality, nor vice versa. Autonomous qualities are relational, too. Aesthetic qualities, for instance, indeed determine how a building could relate to human and nonhuman agents in a given context. A beautiful, well-crafted building is likely to maintain different interactions than an unattractive one.

Buildings are autonomous, because of their formal presence, and relational, because they create, and inhabit, various networks of interactions. Overcoming this opposition could shed more light on the complex but fascinating nature of architecture: its processes, its objects, and its consequences in the built world.