Architectural Competitions on Aging in Denmark Spatial Prototypes to Achieve Homelikeness 1899–2012

Abstract

:1. Introduction

- The organizer’s formulation of the design task and the competition brief with the client’s/organizer’s vision for the new building, physical requirements, and other material;

- The participating architects’ interpretations of the brief into architectonic visions; the proposals of the participating architects’ interpretations of the competition brief with requirements in terms of architectonic visions for buildings and urban space;

- The jury’s evaluation of the submitted proposals to designate a winner; the jury assessment report with evaluations of the submitted proposals and their feasibility in relation to the intentions of the competition.

Nordic Architectural Competitions on Buildings for Societal Use

2. Material and Methods

3. Results

3.1. An Architectural Typology of Space for Aging

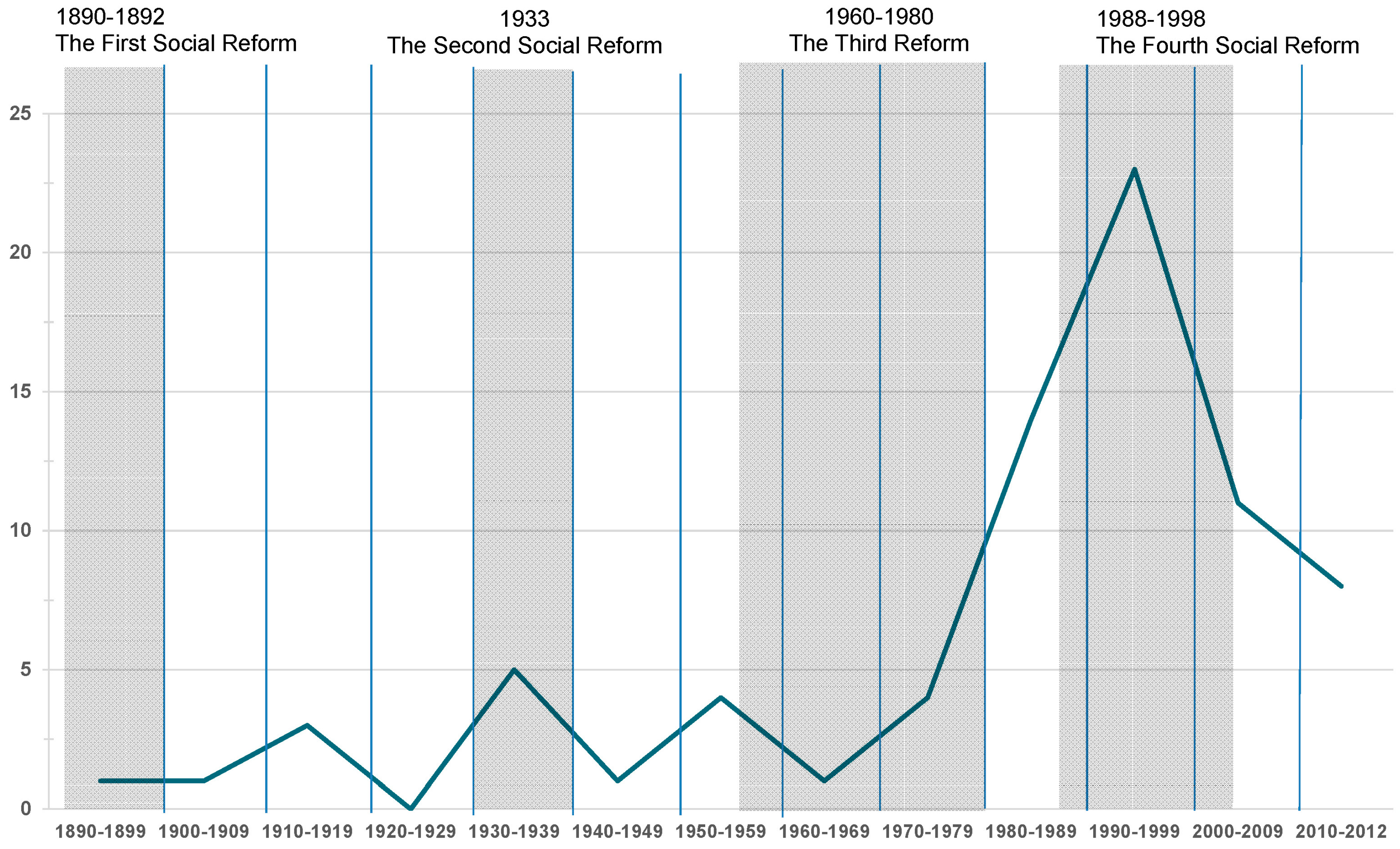

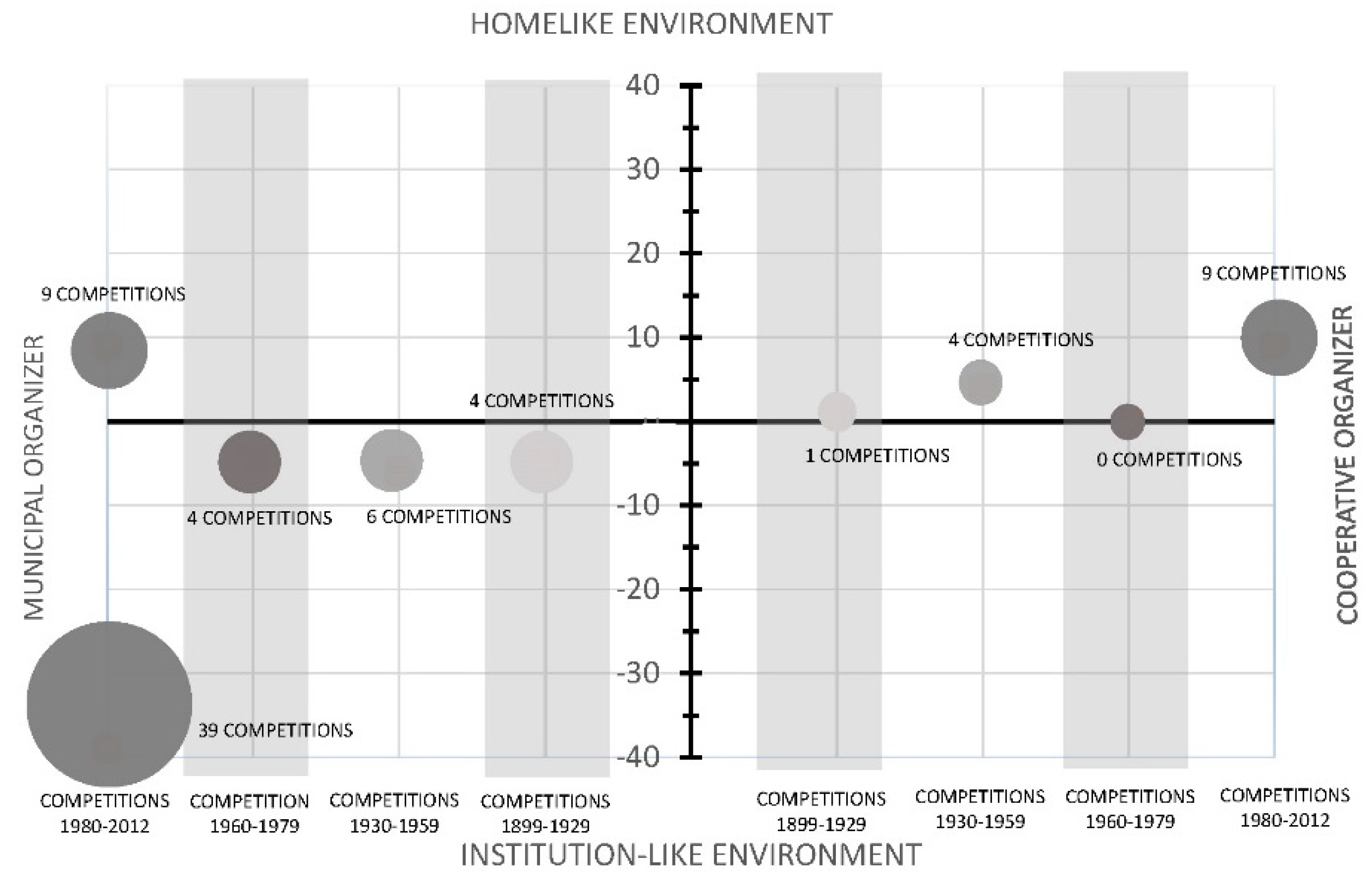

3.2. Architectural Competitions Related to Four Paradigms in Social Legislation

3.2.1. Competitions 1899–1929: Prototypes for Small Pension Housing

A Municipal Prototype Focused on Accommodation

A Cooperative Prototype with Residential Qualities

Conclusions Pertaining to Competitions 1899–1929

3.2.2. Competitions 1930–1959: A New Take on Architecture for Aging

Municipal Prototypes Targeting Accommodation

The Cooperative Prototype Promotes Homelikeness

Conclusions Pertaining to Competitions 1930–1959

3.2.3. Competitions 1960–1979: Architecture for Aging at a Crossroads

Stalemate in Cooperative and Municipal Competitions

Conclusions Pertaining to Competitions 1960–1979

- Municipal homes, which were originally named old people’s homes or older denominations, were renamed residential care homes.

- Municipal pensioners’ homes and the old people’s homes of housing cooperatives were renamed ‘housing for elderly people’.

- In addition to these updated existing concepts, a new prototype for aging was created, i.e., sheltered housing, normally comprising 1–2 room flats often integrated into refurbished older buildings previously used as municipal nursing homes or old people’s homes.

3.2.4. Competitions 1980–2012: Appropriate Space for Aging Reinvented

- Residential care homes in which the architectural design took into consideration high demands on physical accessibility, flexibility, and usability for a wide range of users, including people with disabilities. Thus, the physical environment allowed residents to continue to lead an independent life in small flats with access to communal space for activities, meals, and social contact. In addition, the homes were integrated into a safe and secure care environment with 24-h caregiving.

- Residential housing for senior Danes in which the architectural design incorporated a high level of physical accessibility and flexibility so that a wide range of users, including people with disabilities, could lead a comfortable life, but also allowing for adequate work–environmental requirements for home-based eldercare services. This housing was to be situated near buildings with 24-h caregiving.

Abandoning Old Prototypes—Renewal and Innovation

Conclusions Pertaining to Competitions 1980–2012

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Gieryn, T.F. What buildings do. Theory Soc. 2022, 31, 35–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simmel, G. The sociology of space. In Simmel on Culture: Selected Writings; Frisby, D., Featherstone, M., Eds.; Sage: London, UK, 1997; pp. 137–174. [Google Scholar]

- Lefebvre, H. La Production de L’espace; Anthropos: Paris, France, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Bourdieu, P. Esquisse D’une Théorie De La Pratique. Précédé de Trois Etudes D’ethnologie Kabyle; Éditions Seuil: Paris, France, 1972. [Google Scholar]

- Foucault, M. Des espaces autres. Hétérotopies. Dits et écrits 1984. Archit. Mouv. Contin. 1984, 5, 46–49. [Google Scholar]

- Norberg-Schulz, C. Existence, Space & Architecture; Studio Vista: London, UK, 1971. [Google Scholar]

- Foucault, M. Surveiller et Punir; Gallimard: Paris, France, 1975. [Google Scholar]

- Goffman, E. Asylums: Essays on the Social Situation of Mental Patients and Other Inmates; Penguin Books: New York, NY, USA, 1961. [Google Scholar]

- Adams, A. Medicine by Design: The Architect and the Modern Hospital, 1893–1943; University of Minnesota Press: Minneapolis, MN, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Chupin, J.P.; Cucuzzella, C.; Helal, B. A world of potentialities. Competitions as producers of culture, quality, and knowledge. In Architecture Competitions and the Production of Culture, Quality, and Knowledge: An International Inquiry; Chupin, J.P., Cucuzzella, C., Helal, B., Eds.; Potential Architecture Books: Montreal, QC, Canada, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Bergdoll, B. Competing in the academy and the marketplace: European architecture competitions 1401–1927. In The Experimental Tradition: Essays on Competitions in Architecture; Lipstadt, H., Ed.; Princeton Architectural Press: New York, NY, USA, 1989; pp. 21–51. [Google Scholar]

- Lipstadt, H. The Experimental Tradition: Essays on Competitions in Architecture; Princeton Architectural Press: New York, NY, USA; Architectural League of New York: New York, NY, USA, 1989. [Google Scholar]

- European Commission. Council Directive of 18 June 1992 relating to the coordination of procedures for the award of public service contracts. Off. J. Eur. Union Laws 1992, 209. [Google Scholar]

- Stang Våland, M. “We chose the proposal, in which we could see ourselves:” End user participation in architectural competitions. In The Architectural Competition: Research Inquiries and Experiences; Rönn, M., Kazemian, R., Andersson, J.E., Eds.; Axl Books AB: Stockholm, Sweden, 2010; pp. 233–260. [Google Scholar]

- Volker, L. Deciding about Design Quality: Value Judgements and Decision Making in the Selection of Architects by Public Clients under European Tendering Regulations; Delft University of Technology: Delft, The Netherlands, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Darke, J. The Primary Generator and the Design Process. In Developments in Design Methodology; Cross, N., Ed.; John Wiley & Sons: New York, NY, USA, 1984; pp. 175–188. [Google Scholar]

- Heylighen, A.; Cavallin, H.; Bianchin, M. Design in mind. Des. Issues 2009, 25, 94–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuff, D. Architecture: The Story of Practice; The MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA; London, UK, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Stevens, G. The Favored Circle: The Social Foundations of Architectural Distinction; The MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA; London, UK, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Cross, N. Design Thinking: Understanding How Designers Think and Work; Berg Publishers: New York, NY, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Imrie, R. The corporealization of codes, rules, and the conduct of architects. Perspecta 2004, 35. Available online: http://www.jstor.org/stable/1567348. (accessed on 22 November 2022).

- Schön, D. Designing: Rules, types and worlds. Des. Stud. 1988, 9, 181–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andersson, J.E.; Bloxham Zettersten, G.; Rönn, M. Introduction. In Architectural Competitions, as Institution and Process; KTH Royal Institute of Technology: Hamburgersund, Sweden, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Rustad, R. “Hvad er Tidsmessig Arkitektur”. En Undersoekelse av Arkitekturens Diskursive Rammer Gjennom Tre Arkitektkonkurranser Og Tre Tidssnitt [Define Contemporary Architecture: An Inquiry into the Discursive Framework of Architecture as Reflected through Three Architectural Competitions and Three Epoques]. Ph.D. Thesis, Norwegian University of Science and Technology, Trondheim, Norway, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Tostrup, E. Architecture and Rhetoric: Text and Design in Architectural Competitions, Oslo 1939–1997; Andreas Papadakis Publisher Ltd: London, UK, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Andersson, J.E. Architecture and the Swedish welfare state: Three architectural competitions that innovated space for the dependent and frail ageing. J. Ageing Soc. 2014, 35, 837–864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dobloug, M. Bak Verket. Kunnskapsfelt Og Formgenerende Faktorer i Nyttearkitektur 1935–1985 [Behind the Work. Knowledge Fields and Factors that Shaped Architecture for Societal Use 1935–1985]. Ph.D. Thesis, Oslo School of Architecture and Design, Oslo, Norway, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Möller, K.; Knudstrup, M.A. Trivsel i Plejeboligen: En Antologi Om Trivselfaktorer i Plejeboliger [Feeling at Home in Residential Care Homes: An Anthology about Aspects Important for Feeling at Home in Residential Care Homes]; Syddansk Universitetsforlag: Odense, Denmark, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Hansen, E.P. Plejeboligen Til Fremtidens Aeldre: Inspiration Fra Foreliggende Forskning Og Undersoegelser [Future-Oriented Housing for Older People with Care: Inspiration from Ongoing Research and Inquiries]; KORA (The National Research Institute of Municipalities and Counties): Copenhagen, Denmark, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Energistyrelsen. Modelprogram for Fremtidens Velfaerdsinstitutioner [Model Programme for Future-Oriented Buildings for Societal Use]. Energistyrelsen, Copenhagen. 2013. Available online: www.modelprogram.dk (accessed on 22 November 2022).

- Ricoeur, P. Architecture et Narrativité. Typed Manuscript Archived on the Fonds Ricoeur Website. Available online: http://www.fondsricoeur.fr/uploads/medias/articles_pr/architectureetnarrativite2.PDF (accessed on 30 June 2016).

- Gschwandtner, C.M. Space and Narrative: Ricoeur and a Hermeneutic Reading of Place. In Place, Space and Hermeneutics: Contributions to Hermeneutics; Janz, B., Ed.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2017; Volume 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flyvbjerg, B. Five misunderstandings about case-study research. In Qualitative Research Practice; Seale, C., Gobo, G., Gubrium, J.F., Silverman, D., Eds.; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA; London, UK, 2004; pp. 420–434. [Google Scholar]

- Yin, R.K. Case Study Research, Design and Methods; Sage Publications, Inc: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Konkurrenceudvalget. Registrant. Arkitektkonkurrencer 1907–1982 [Overview. Architectural Competitions 1907–1982]; Konkurrenceudvalget, Akademisk Arkitektforening. Dansk Arkitekters Landsforbund, Akademisk Arkitektforening: Copenhagen, Denmark, 1982. [Google Scholar]

- Konkurrenceudvalget. Registrant. Arkitektkonkurrencer 1982–1992 [Overview. Architectural Competitions 1982–1992]; Konkurrenceudvalget, Akademisk Arkitektforening. Dansk Arkitekters Landsforbund, Akademisk Arkitektforening: Copenhagen, Denmark, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Konkurrenceudvalget. Registrant. Arkitektkonkurrencer 1993–2001 [Overview. Architectural Competitions 1993–2001]; Konkurrenceudvalget, Akademisk Arkitektforening. Dansk Arkitekters Landsforbund, Akademisk Arkitektforening: Copenhagen, Denmark, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Brummett, B. Techniques of Close Reading; SAGE Publications: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Andersson, J.E. Architecture and Ageing: On the Interaction between Frail Older People and the Built Environment. Ph.D. Thesis, KTH Royal Institute of Technology, Stockholm, Sweden, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Waern, R. Tävlingarnas Tid: Arkitekttävlingars Betydelse i Borgerlighetens Sverige. [The Era of the Architectural Competitions: The Importance of Competing in Architecture in the Fin-De-Siècle Stockholm]; Arkitekturmuseet: Stockholm, Sweden, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Åman, A. Om den Offentliga Vården: Byggnader Och Verksamheter Vid Svenska Vårdinstitutioner under 1800-Och 1900-Talet [On Societal Care: Activities and Buildings for Various Swedish Societal Institutions during the 19th and 20th Century]; LiberFörlag & Sveriges Arkitekturmuseum: Stockholm, Sweden, 1976. [Google Scholar]

- Andrews, G.J.; Philips, D.R. Ageing and Place: Perspectives, Policy, Practice; Routledge: London, UK, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Herfray, C. La Vieillesse En Analyse; Éditions Arcanes/Éditions Érès: Paris, France, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Nielsen, T. Byudvikling og velfaerd [Development of cities and welfare]. In Velfaerd—Dimensioner Og Betydninger [Welfare—Dimensions and Implications]; Jensen, P.H., Ed.; Bogforlaget Frydenlund: Copenhagen, Denmark, 2007; pp. 300–328. [Google Scholar]

- Bruus, P. Om den “lille” socialreform i 1920’erne [On the “little” social reform during the 1920s]. In Den Danske Velfaerdssstats Historie: Antologi [The History of the Danish Welfare State, An Anthology]; Ploug, N., Henriksen, I., Kaergård, N., Eds.; Socialforskningsinstituttet: Copenhagen, Denmark, 2004; pp. 70–89. [Google Scholar]

- Jonasen, V. Den kommunale danske velfaerdsstat—Gennem fire socialreformer og fire mellemtider [The municipal Danish welfare state through four social reforms and four intermediary periods]. In Den Danske Velfaerdsstats Historie [The History of the Danish Welfare State]; Ploug, N., Henriksen, I., Kaergård, N., Eds.; Socialforskningsinstittutet: Copenhagen, Denmark, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Kolstrup, S. Kommunen—Velfaerdstatens spydspids [The municipality—The spearhead of the welfare state]. In 13 Historier Om Den Danske Velfaerdsstat [13 Histories about the Danish Welfare State]; Petersen, K., Ed.; University Press of Southern Denmark: Odense, Denmark, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Kolstrup, S. Velfaerdsstatens Roedder: Fra Kommunesocialisme Til Folkepension [The Roots of the Welfare State: From Municipal Socialism to Public Pensions]; Selskabet til Forskning i Arbejderbevaegelsens Historie, SFAH: Copenhagen, Denmark, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt, V. “De gamles hjem” i Aarhus. [The old peopleis home in Aarhus]. In Architekten: Meddelser Fra Akademisk Architektforening; Akademisk Arkitektforening: Copenhagen, Denmark, 1904; Volume 11, pp. 117–122. [Google Scholar]

- Architekten. Konkurrencen om de gamles hjem [The architectural competition on the old people’s home]. In Meddelser fra Akademisk Architektforening; Akademisk Arkitektforening: Copenhagen, Denmark, 1900; Volume 2, pp. 142–143. [Google Scholar]

- Architekten. “De gamles hjem” i Aarhus [The old people’s home in Aarhus]. In Meddelser Fra Akademisk Architektforening; Akademisk Arkitektforening: Copenhagen, Denmark, 1907; pp. 117–122. [Google Scholar]

- Architekten. Konkurrencen om alderdomshjem i Svendborg [The architectural competition about the old people’s home in Svendborg]. In Meddelser Fra Akademisk Architektforening; Akademisk Arkitektforening: Copenhagen, Denmark, 1907; Volume 9, p. 204. [Google Scholar]

- Architekten. Alderdomshjemmet i Svendborg. Opfert 1909–1911 [The old people’s home in Svendborg, erected 1909–1911]. In Meddelser Fra Akademisk Architektforening; Akademisk Arkitektforening: Copenhagen, Denmark, 1913; Volume 15, pp. 489–492. [Google Scholar]

- Architekten. Alderdomshjem på Frederiksberg [The old people’s home in Frederiksberg]. In Meddelser Fra Akademisk Architektforening; Akademisk Arkitektforening: Copenhagen, Denmark, 1919; Volume 21, pp. 428–433. [Google Scholar]

- Architekten. Alderdomshjem i Naestved [The old people’s home in Naestved]. In Meddelser Fra Akademisk Architektforening; Akademisk Arkitektforening: Copenhagen, Denmark, 1917; Volume 19, pp. 405–409. [Google Scholar]

- Architekten. Konkurrencen om alderdomshjem for arbejdere [The architectural competition about an old people’s home for workers]. In Meddelser fra Akademisk Architektforening; Akademisk Arkitektforening: Copenhagen, Denmark, 1912; Volume 14, pp. 270–271. [Google Scholar]

- Architekten. Konkurrencen om alderdomshjem for arbejdere [The architectural competition about an old people’s home for workers]. In Meddelser fra Akademisk Architektforening; Akademisk Arkitektforening: Copenhagen, Denmark, 1913; Volume 15, pp. 385–390. [Google Scholar]

- Vestergaard, H. Boligpolitik i velfaerdsstaten [Housing politics in the welfare state]. In Den Danske Velfaerdsstats Historie: Antologi [The History of the Danish Welfare State: An Anthology]; Ploug, N., Henriksen, I., Kaergård, N., Eds.; Socialforskningsinstittutet: Copenhagen, Denmark, 2004; pp. 260–286. [Google Scholar]

- Socialministeriet. Betaenkning Vedroerende Alderdomshjem Og Plejehjem [Report Concerning Old People’s Home and Nursing Homes]; Betaenkning nr 138; Socialministeriet: Copenhagen, Denmark, 1962. [Google Scholar]

- Arkitekten. Konkurrence om et alderdomshjem for Gentofte Kommune [Architectural competition for a new old people’s home in the municipality of Gentofte]. In Meddelser fra Akademisk Arkitektforening; Akademisk Arkitektforening: Copenhagen, Denmark, 1938; pp. 79–83. [Google Scholar]

- Arkitekten. Hjem for kronisk syge i Aarhus [Home for chronically ill people]. In Meddelser fra Akademisk Arkitektforening; Akademisk Arkitektforening: Copenhagen, Denmark, 1948; pp. 165–166. [Google Scholar]

- Gottschalk, G.; Platz, M. Modernisering af Pensionistboliger i Koebenhavns Kommune [Modernisation of Pensioners’ Homes in Copenhagen]; Statens Byggeforskningsinstitut, SBi: Copenhagen, Denmark, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Arkitekten. Guldbergshave. Arkitekten Maanedshaefte. Utgivet af Akademisk Arkitektforening. Tidskr. Arkit. Og Dekor. Kunst. J. 1939, 41, 88–89. [Google Scholar]

- Gottschalk, G. Fortidens og fremtidens boliger for aeldre [Historical and future-oriented housing for older people]. Arkitekten 2008, 3, 41–45. [Google Scholar]

- Hansen, T. Leve—Og Bomiljoer [Living and Housing Milieus]; Munksgaard: Copenhagen, Denmark, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Nygaard-Hansen, P. Behovet for plejehjem: Referat af rundbordssamtale på Hindsgavl Slot den 7. december 1963 [The need of nursing homes: Report from discussions on Hindsgavl castle on 7 December 1963]. In Rundbordssamtale 15; Teglindustriens Tekniske Tjenste: Copenhagen, Denmark, 1963. [Google Scholar]

- Boligministeriet. Projektering af plejehjem [On programming nursing homes]. In Boligministeriets Udvalg Vedroerende Opforelse Og Indretning Af Plejehjem [Ministry for Housing, Committee on Construction and Design of Nursing Homes]; Boligministeriet: Copenhagen, Denmark, 1967. [Google Scholar]

- Arkitekten. Plejehjem i Skagen [Nursing home in Skagen]. Meddelser fra Akademisk Arkitektforening; Akademisk Arkitektforening: Copenhagen, Denmark, 1980; pp. 290–291. [Google Scholar]

- Boll-Hansen, E.; Dahl, A.; Gottschalk, G.; Palsig Jensen, S. Aeldre i Bofaelleskab [Older People Living in Senior Co-Housing Facilities]; Statens Byggeforskningsinstitut, SBi/Amternes og Kommunernes Forskningsinstitut: Copenhagen, Denmark, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Pedersen, M. Det Store Eksperiment, Hverdagsliv i Seniorbofaelleskaberne [The Great Experiment—Everyday Living in Senior Co-Housing Facilities]; Statens Byggeforskningsinstitut, SBi, Aalborg Universitet: Copenhagen, Denmark, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Boligministeriet. Vejledning 1976 [Guidelines 1976]; Boligministeriet: Copenhagen, Denmark, 1976. [Google Scholar]

- Leeson, G.W. My Home Is My Castle-Housing in Old Age. J. Hous. Elder. 2006, 3, 61–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foerlev, B.; Gottschalk, G.; Damkjaer, K.; El-Kholy, K.; Bonde Nielsen, E.; Thyssen, S.; Aasborg, M. Boligforhold, Pleje Og Omsorg i Ti Koebenhavnske Plejehjem [Housing Conditions: Caregiving and Nursing in 10 Nursing Homes in Copenhagen]; Statens Byggeforskningsinstitut, SBi: Copenhagen, Denmark, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Aeldrekommissionen. Sammenhang i Aeldrepolitikken [Contexts in Politics for the Senior Population]; Aeldrekommissionen: Copenhagen, Denmark, 1982. [Google Scholar]

- Gottschalk, G.; Potter, P. Better Housing and Living Conditions for Older People: Case studies from Six European Cities; Danish Building Research Institute: Copenhagen, Denmark, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Dehan, P. L’Habitat Des Personnes Agées, Du Logement Adapté Aux EHPAD, USLD, et Unités Alzheimer; Le Moniteur: Paris, France, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Sprenger, T. Indretning af Aeldreboliger M Fl: En Vejledning [Design of Housing for Elderly People: A Guide]; Forlaget Kommuneinformation: Copenhagen, Denmark, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Leeson, G.W. Aeldre Sagens Fremtidsstudie; Rapport Nr 1; Bolig Aeldresagen: Copenhagen, Denmark, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Social_og_Integrationsministeriet. Serviceloven [Law on Social Services]; Folketing: Copenhagen, Denmark, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Arkitekten. 1996. Aeldre-/aktivitetscenter og 20 aeldreboliger samt bebyggelseplan for yderligare 40 boliger og div. kulturinstitutioner [Eldercentre and 20 dwellings for older people with development plan for some 40 more dwellings and institutions for cultural activities]. In Meddelser fra Akademisk Arkitektforening; Akademisk Arkitektforening: Copenhagen, Denmark, 1996; pp. 79–83. [Google Scholar]

- Frederiksberg Kommune. Kredsens Hus—Frederiksberg: Inbudt Projektkonkurrence: Dommerbetaenkning; FK Ejendom: Frederiksberg, Denmark, 2010. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Andersson, J.E. Architectural Competitions on Aging in Denmark Spatial Prototypes to Achieve Homelikeness 1899–2012. Architecture 2023, 3, 73-91. https://doi.org/10.3390/architecture3010005

Andersson JE. Architectural Competitions on Aging in Denmark Spatial Prototypes to Achieve Homelikeness 1899–2012. Architecture. 2023; 3(1):73-91. https://doi.org/10.3390/architecture3010005

Chicago/Turabian StyleAndersson, Jonas E. 2023. "Architectural Competitions on Aging in Denmark Spatial Prototypes to Achieve Homelikeness 1899–2012" Architecture 3, no. 1: 73-91. https://doi.org/10.3390/architecture3010005

APA StyleAndersson, J. E. (2023). Architectural Competitions on Aging in Denmark Spatial Prototypes to Achieve Homelikeness 1899–2012. Architecture, 3(1), 73-91. https://doi.org/10.3390/architecture3010005