Abstract

Iconic architecture and landscape architecture are most often understood through photographic media that mediates between the idea and the reality for those learning to design. The drastic lockdown responses to COVID-19 and the limitations on local and international travel highlighted the importance of the visual and the potential of the virtual. However, visual media can also be understood as systems that go far beyond a strict representation of an object. In this climate where publicity, politics, and perception play ever more crucial roles, representations of iconic architecture and landscapes increasingly blur the boundaries between the imaginary and the tangible. This paper examines the experience of iconic architecture and landscape in four iconic European cities (Paris, Barcelona, Seville, and Lisbon) as seen through the eyes of fifty postgraduate architecture, interior architecture, and landscape architecture students from New Zealand. It compares their understanding of a building or landscape from its photographic image before engaging with the physical reality. Students were asked to first identify iconic architecture and landscape, then closely analyze and document the essential qualities which established its pre-eminence. A subsequent visit to each of the places provided the opportunity for comparison and the testing of the realities and fictions of the icons themselves. Our research finds that today’s architecture students are savvy and sophisticated consumers of technology. It also presents FABRIC (finding, assimilating, being, reflecting, introspecting, and concluding), a conceptual framework that offers additional scaffolding for educating design students through experiential learning in a time of travel restrictions.

1. Introduction

Throughout history, architectural icons have exemplified the aspirations and values of society. However, in the past few decades, iconic and spectacular architecture and landscape architecture have been used to proliferate and fuel urban economic competition within a globalised culture industry [1]. The term iconic has been defined by two central characteristics [2]. First, it must be famous. Second, it must be imbued with meaning that is both symbolic for a culture and/or a time and is worthy of presenting beautifully what is being represented [1,3]. From an architectural perspective, buildings have been understood to symbolise good taste, power, and status through the attention paid to the identity of the architect [4]. Iconic architects and landscape architects are those who design architecture and landscape architecture that is unique and unreproducible, and which contributes to their global brand expressed in leading cities throughout the world. Julier [5] describes the ‘hard branding’ of cultural institutions, including new museums, arts complexes, and theatres that are frequently assigned an iconic status. Similarly, Koolhaas observes that shopping is the number one tourist activity, and concludes that retail is the “single most influential force on the shape of the modern city” [6]. In this way, an architectural project can be seen as both a product and a media representing a city, a client, a place, or even a real estate product to market [7]. Most recently, with the chaos of a global pandemic, climate change, political outcry, and strained mental health, our relationship with iconic architecture and landscape architecture is undergoing change as it seeks to forge a new language for a society in search of a new identity.

In response to the restrictions imposed by COVID-19 and for architectural education around the globe, the requirements of social distancing and travel restrictions have moved lectures, studio work, presentations, discussions, and final design reviews to virtual classrooms and meeting rooms using various platforms supporting the virtual meeting environment. Virtual site visits are offered as potential replacements for physical experience. This research asks what are the necessary tools to understand architectural and landscape icons in a time of travel restrictions. To understand the implications of virtual site visits, we examine the experience of iconic architecture and landscape architecture in four iconic European cities (Paris, Barcelona, Seville and Lisbon) as seen through the eyes of fifty undergraduate and postgraduate architecture, interior architecture and landscape architecture students from New Zealand. This paper compares their understanding of a building, interior or landscape from its ‘virtual’ photographic image prior to their visit with their understanding following engagement with the physical reality. It seeks to uncover the scaffolding necessary for experiential learning in a mixed-mode architectural education environment.

2. Literature Review

While the term ‘iconic’ generally signifies a building’s particular ability to produce a memorable image, i.e., its ‘imageability’ [8], such images are usually photographic and part of a series of ephemeral impressions in our digital age in an ever-expanding universe [9]. While the notion of iconicism is comprehensible and straightforward for everyone, for those in the architectural disciplines, including landscape and interior architecture, iconic architecture is more commonly established by its relationship with the photograph and the digital model, where computer visualisation is used to see what is often unseen [10].

Architectural designers use photography in a variety of ways. First, they use it as visual surveying, recording, or documenting to convey as much information on an icon as possible. Second, illustrative photography documents aspects of the icon in a careful artistically composed form. Third, picture photography is employed where the primary concern is to tell the iconic narrative of the object and to get closer to the designer’s perception of space [11]. The architectural photograph, by its nature, prioritises sight above all of our other senses. Nevertheless, since the experience of an icon is not limited to vision, photography limits the knowledge of the observer to a single focus due to the choice of angles and framing, which makes that view more apparent and comprehensible at the expense of the entire whole [12,13]. A photograph can be held in the hands of the observer and contemplated in solitude where the viewer is distanced from the subject and independent of place [14,15].

Drawings, photography, and digital technology are essential to establishing the iconic status of buildings, interiors, or landscapes [16]. The drastic lockdown responses to COVID-19 and the limitations on local and international travel eliminated the field trip/excursion/site visit as a learning opportunity and highlighted the importance of the visual. However, these images are anything but ‘present’, ‘corporeal’, or three-dimensional (that is, ‘iconic’ in the word’s original sense). Instead, they borrow their iconicity from their ability to multiply infinitely while at the same time retaining their memorability [17]. The power of the image in producing iconicity affects how people give credence to the building and landscapes and, in some cases, the architects they represent. Iconicity works and persists since the buildings, interiors, and landscapes express both symbolic and aesthetic values.

To take a photograph is to decontextualise the object from its physical adjacencies and the societal circumstances in which it is framed [18,19]. Buildings, interiors, and landscapes of different scales and types are portrayed side by side in publications, reconfigured in new visual relationships, where any meaning that is not inherent in the image itself or in the actions or objects it portrays is lost. In the real world, meanings are defined by the context and the discourse in which they are framed [20,21]. Schumacher, as cited in Sklair, argues “the worst offence of architectural photography, however, is its ability to make terrible buildings look good, photographing a building out of context truly tells a lie’. The images people see of buildings and spaces often do not prepare them for the emotional, in some cases described as spiritual, impact of direct experience. The idea and representation of buildings can be much better than the physical building.” [3]. A photograph thereby becomes an interpretation that is never a truly objective description of an icon [15], which leads to the importance of experience for a learning environment.

Much has been written on the importance of experience for student engagement and learning through field trips [22,23,24,25]. For those in the architectural disciplines, site visits, excursions and field trips are essential for forming professionals who can respond appropriately when confronted with making places through planning and design. Field trips to significant architecture and landscape architecture also allows students to explore the application of the theoretical principles in practice and meet professionals who can explain their designs and answer questions. Kolb’s experiential learning theory supports the belief that learning is a process whereby knowledge is created through the transformation of experience. An important feature of Kolb’s theory is that it offers a wide range of experience definitions, from those that involve using our senses, to those that involve abstract thinking using logic and reasoning [26]. Empirical studies support the notion that it is concrete experience that leads to the greatest degree of individual learning [27]. Klein [28] suggests that mere transmission of information does not guarantee reception and that students must be an active party with the information. Experiential learning theories emphasise the importance of the participants learning by doing but then reflecting on the experience [23,29,30]. Learning occurs as the participants interact and assimilate new information into that which they already know [31].

One problem with iconic architecture is that the experiences of the building, landscape, interior are often staged by tourism suppliers in such a way that they never obtain an authentic experience. Mehmet et al. [32] found that the dimensions of education and entertainment do not affect satisfaction; however, aesthetics, and escapism do. Pine and Gilmore’s [33] model of the four dimensions of experience offers a valuable framework for understanding student preferences. According to them, the richest experiences are those that combine feeling, learning, being, and doing. The outdoor experience allows students to see their landscape/building/interior in context and better understand the associated landscape [34]. Krakowka [24] adopts the Kolb framework to explain the importance of fieldtrips to the teaching of geography, aligning Kolb’s four learning stages with four examples for geography. This study suggests that modifying these frameworks can offer a valuable tool for architecture students researching the built environment.

3. Materials and Methods

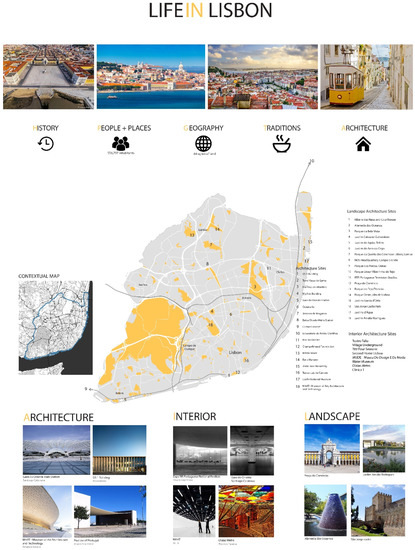

Using an opportunistic sampling method, four iconic European cities (Paris, Barcelona, Seville and Lisbon) were selected due to their ease of access, affordability, and climate (Figure 1). From an International Field Study course, running from November 2019 to February 2020, 50 New Zealand students from architecture (22), landscape architecture (17), and interior architecture (11) participated in this research as part of their study (Figure 2). First, students were asked to research, in groups, the context and culture of each city and then identify iconic architecture and landscapes from the late 20th century to the present (Table 1). Iconic buildings, landscapes, and interiors were identified from recent architectural publications (Platform, ARQ, Mark, Topos, etc.) and websites (such as ArchDaily, Dezeen, Landezine, Land8, etc.). From this list, they each selected one building/landscape/interior from each city. The second assignment involved analysing and documenting the essential qualities that established these buildings/landscapes and interiors pre-eminence (Table 1). Their written analysis served as an information guide, which students presented when the building/landscape/interior was visited. As each city was visited, the groups reported on the overall context of the city and its cultural highlights. Groups were divided by discipline and buildings/landscapes/interiors were presented and discussed in situ. The visits provided the opportunity for close analysis as students photographed key elements of the building/landscape/interior and the chance to discuss the importance of authentic context as well as the realities and fictions of the icons themselves. A summary of the student learning process is provided in Figure 3.

Figure 1.

Location of the countries and cities visited.

Figure 2.

Break-down of student numbers by discipline.

Table 1.

Breakdown of assignments.

Figure 3.

Diagram of the student learning process.

Shortly after introducing and viewing their building/landscape/interior, the presenting student was asked to complete their third assignment, which included an eight-point questionnaire (Table 1 and Table 2). The questionnaire asked students to compare their pre-trip research with their actual visit and had to be submitted by the end of the day of the visit itself. The questions aimed to capture student’s initial reaction, their emotional and physiological response, their experience with others and their overall understanding of the iconic element. Following reflection and introspection, they documented both the tangible and intangible elements of their experience in their final assignment (Table 1). The assignment also identified new possibilities and opportunities for future design and was due four weeks after the field trip was completed.

Table 2.

Survey questions.

All interviews were transcribed verbatim and analysed using interpretative phenomenological analytic techniques [35,36]. This method permits the researchers to explore and extract meaningful inferences based on personal worlds, emphasising hermeneutics, experience, and in-depth analysis. The IPA coding identifies themes and super-themes while observing context, language used, and content [37,38]. Students and locations were de-identified, then grouped by discipline. From the coding, key themes were extracted adopting an inductive approach and representative quotes were selected, question by question. From the themes generated, the number of comments per theme was calculated and converted into percentages so as to show the significance of the comment. This was then evaluated against the literature to develop a conceptual framework for experiential learning by those designing the built environment.

4. Results

The questionnaire focused on comparing the visited icon with the student research, including photography, context, and data. Questions were loosely grouped in four categories: (1) initial reaction to the building, including stand out features and their reflections on the differences between the real and the photograph; (2) reflection and introspection relating to the effect of the building on them, the senses engaged and any bodily changes or states; (3) the influence of the experiences of others; and (4) their conclusions leading to new understandings and knowledge that could be taken into future design work.

Overall, common themes that arose across all answers were scale (big and small), the experience of space, which merges with the idea of embodiment and sensory feeling, and the addition of physiological effects and visual aesthetics (Table 3). The three-way interplay between researching a site from afar, visiting the site, and then photographing it intensified these themes. Unlike other themes, aesthetics was described in both positive and negative ways; students were very detailed about whether their site was beautiful or very unappealing, and these comments have an interesting interaction with optical vision and other senses such as smell, hearing, and touch. Students felt either overwhelming disappointment or intensive satisfaction when visiting the site rather than having a neutral reaction.

Table 3.

Student quotes about initial experiences by discipline.

When students were asked to describe their initial experience of their building/landscape/interior, four main themes emerged: the impact of scale 28.5%, the power of aesthetics/beauty 22.8%, the sense of cohesion 19% and, finally, the sensory impact 12.3%.

Differences were noted by discipline when reviewing first impression comments (Table 4). For example, comments regarding cohesion/complexity were predominantly made by students from architecture and landscape architecture, whereas interior architecture students were more likely to report on sensory experience.

Table 4.

Examples of disciplinary differences.

When asked to analyse the pre-trip research and photographs against the experience of the visit, student comments could be grouped into four main categories: differences in scale (39.8%), complexity in details (24.2%) differences in aesthetics/appearance (18.4%), and differences related to maintenance (17.4%). The most significant difference between the studied photographs and the actual building/landscape/interior was that of scale (including interior volume). The spaces were portrayed as either much larger or much smaller than the experience garnered from the visit. Architecture and landscape architecture students made the majority of the comments regarding scale, whereas interior architecture students were more likely to comment on the aesthetics and details (Table 5). A similar question asked what aspects, dimensions, etc., stood out. Here, the impact of the building scale (32%) was equal to that of the building details and their complexity (32%). Following this was ‘other’ (24.3%), which mainly focussed on elements extraneous to the architecture, followed by lighting (11.5%).

Table 5.

Student quotes comparing expectation to experience by discipline.

Many students found that the visited building/landscape/interior’s aesthetic qualities were not easily captured through photography (Table 6).

Table 6.

Student comments about the influence of photography by discipline.

Many students were surprised about the change of context from that in the photographs (Table 7).

Table 7.

Student quotes discussing the impact of context by discipline.

The question of emotional effect is raised when we compare a static image with a piece of architecture or landscape architecture which is experienced by the body (Table 8). Following on from their initial experience, students were then asked to examine the senses that had been activated, namely sight 42.9%, sound 24.8%, touch/haptic 23.7%, and smell 8.4%.

Table 8.

Student comments regarding sensory activation by discipline.

Certain elements stood out for students, dominating their initial experience. In particular, elements that could only be captured by the close investigation possible in a site visit (Table 9).

Table 9.

Student comments regarding outstanding elements by discipline.

A secondary question asked about awareness of bodily changes or states, which was followed by a question regarding the emotional impact of the building/landscape/interior (Table 10). The first question posed some problems for the students, most (33.3%) reported on temperature or their emotional response (21%), and feelings such as excitement, or calmness/relaxation and their sensory experience (5%).

Table 10.

Student experiences of bodily changes by discipline.

Finally, when asked how the experience emotionally affected the students there were mixed emotions, 43.5% of the students had an overall positive experience, while 56.5% felt disappointment when confronted with the reality (Table 11).

Table 11.

Student quotes about emotional impact by discipline.

COVID requirements for social distancing and the experience of visiting a building/landscape/interior with others can affect the experience of place and space. Students were asked about how the experience of others impacted their own experience. Four themes emerged from the analysis: enhanced enjoyment (38.1%), developed understanding (36.8%), distraction (15.7%), and other (9.2%). Of these, 75% of students felt that the presence of similar others enhanced their experience of the icon through a shared emotional experience, followed by a sharing of intellectual ideas. Negative experiences were associated with either disinterest by colleagues, by the distraction of other tourists, or a difference of opinion (Table 12).

Table 12.

Student comments about the impact of others on their experience by discipline.

Once the initial excitement wore off and students started to engage with the components of the architecture, the group experience heightened their understanding (Table 13).

Table 13.

Student evaluative comments after group discussion by discipline.

However, not all experiences with a group were positive (Table 14).

Table 14.

Student quotes regarding negative aspects of others by discipline.

When asked if their understanding of the building/interior/landscape changed after their visit, the students overwhelmingly (80.5%) reported a change from what they had gleaned from photographs (Table 15).

Table 15.

Student comments about changes of understanding by discipline.

Students also learned how photographs can lie (Table 16).

Table 16.

Student comments about the dangers of learning from photographs by discipline.

5. Discussion

The primary sources of information in architecture schools come from online resources, which contain visual images and picture-dominated books and periodicals. COVID imperatives for staying at home, combined with the closure of libraries, bookstores, and government offices, limited information gathering to online sources, where images are tampered with through fragmented, cropped, framed and touched up versions of the buildings/interiors and landscapes (Figure 4). For these reasons, teaching context, including how cities use icons for branding, is particularly crucial. Students need to understand the limitations of their sources and why architectural images may be deliberately misrepresented. As the context is laden with meaning, knowledge of the global setting also needs to be acknowledged in current times of globalisation. Contextualising, or FINDING, is an essential first step for architecture, interior architecture, and landscape architecture students. This is an additional step to that proposed by Kolb [23] and modified by Krakowka [24].

Figure 4.

Example of student work produced in the first step (Finding) of the FABRIC framework.

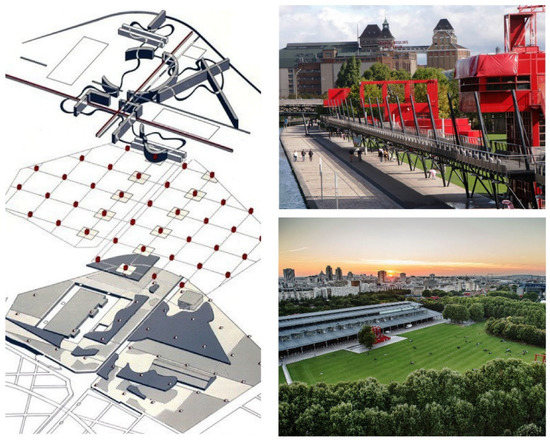

Once students understood the implications of context, they then had to examine the range of ‘potential’ iconic buildings/landscapes/interiors to identify those worthy of further investigation (Figure 5). Krakowka [24] proposes planning as the first step of understanding, wherein, for geography this involves looking at maps, researching the area of the field trip, planning the route, etc., and for Kolb [23] it is active experimentation. At this stage, much valuable information can be obtained from online resources. Aerial photography, building and interior images and plans can provide much detail about a building and show overlooked, invisible or inaccessible parts. This investigation process aligns with traditional delivery, which is primarily in a lecture or studio format supplemented with online investigation. ASSIMILATING information at this stage is important in order for students to complete their initial assessment which then they will compare to the ‘real’ during the site visit. This step also provides a sense of anticipation, thereby engaging with emotion.

Figure 5.

Example of student work produced in the second step (Assimilating) of the FABRIC framework.

While some education activities were successfully replaced virtually during the COVID-19 pandemic, many activities were affected by the measures taken to limit the spread of the disease. Community events, exhibitions, and activities were cancelled or postponed. Site visits and field trips were not possible and their virtual replacement often encountered constraints, with access to equipment and the difficulty in collecting on-site material to prepare a virtual tour [39]. This eliminated the opportunity for physically BEING in the space. Studying space physically benefits multi-sensory experience, thus increasing the understanding of the way space is arranged. This critical step of experiential learning aligns with ‘concrete experience’ as noted by Kolb and ‘DO’ as modified by Krakowka.

Without the physical experience of architecture, it is easy to underestimate the extent of this deficiency for our perception and understanding [40]. Students found that either the building, interior or landscape in question did not perform to the image built up or read from the photographs, or that the building, interior or landscape added no more to the experience that the photograph gave (Table 3 and Table 11). While many would expect a photograph to be a ‘virtual twin’ of the physical building/interior/landscape, the incidences of digital alterations to enhance desirability, the curated selection of photographic images to show only selected spaces, and the ageing of the building/interior/landscape over time, all contributed to the lack of authenticity.

“The prettier lies—the greater the seduction—the essential narrowing of architecture to an image may be part of its eternal hopeless political promise’ …“High profile buildings become a laboratory of invested meaning and naturally disappointment.”[41]

Many of our students experienced the feeling of arriving at a building, interior or landscape, well known or not and being disappointed (Table 17).

Table 17.

Student quotes by discipline.

Our research found that when students visited their building/interior/landscape, they were now able to effectively ‘receive’ the information gathered as they compared their expectations with their experience. This action of thinking profoundly and reflectively is directly aligned with Step 3 from Kolb and Krakowka’s frameworks.

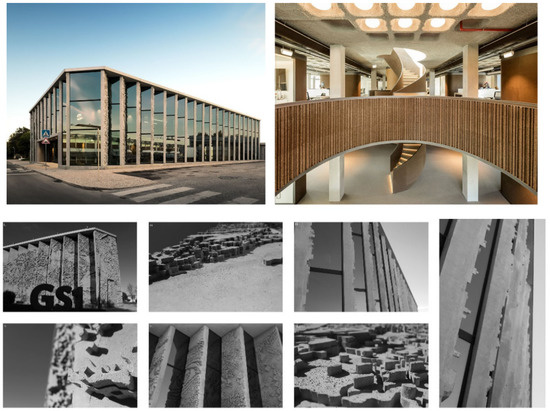

Our students engaged with internalised critical theory REFLECTING on their buildings (Figure 6). Much of the learning experience was heightened by being physically located in the space, promoting social encounters and active participation of body and senses [42]. Students reported that scale, complexity, aesthetics, and sensory experience deepened the engagement with the physical icon. Moreover, the scale was reported as the most significant difference in the experience of the icon through photography when compared with the real experience. Scale is the projective size of a place relative to the human body and plays an important role when experiencing a place [43]. It is through scale that people perceive the relationships between objects, and establish a mind-map that defines the way in which their body acts.

Figure 6.

Published photographs compared with student work and reflection (reflecting) of the FABRIC framework.

For landscape architecture students, issues related to climate and temperature were mentioned as the most predominant difference. For example, landscape architecture students visited the sites in late autumn/early winter, while most photographs represented sites in optimal summer conditions. The temporal difference in experience between the real and the photograph directly affects the experience of a place and its vegetation. This difference did not affect students in architecture or interior architecture in the same way. For landscape architecture students, it is through the spatial and climatic conditions of a place that social desires and emotions are conditioned [44].

Next, INTROSPECTING involved the close examination of emotional response, the experience of buildings/landscapes/interiors and the abstraction of intangible concepts, themes and ideas. Many have theorised about the importance of introspection and phenomenology and have suggested that if architecture or landscape architecture is predicated on a bodily experience, we are in the realm of ‘atmosphere’ [17,45,46,47,48]. Recalling the experience of immersion in architectural space is deemed to disturb or even inhibit its perception as an image [17]. Regarding Kolb and Krakowka’s frameworks, this step (Introspecting) is labelled as Abstract Conceptualisation (Kolb) or THINK (Krakowka). However, while aligned with Kolb, it is separate from the definition of THINK (Krakowka), which is of particular importance for design students.

A final step for our architecture students was CONCLUDING, to end their examination of the iconic object and consider how their understanding of architecture, interior architecture and landscape architecture had changed and how they might then take what they had learned into future design. This is an additional step to Kolb and Krakowka. On completion, architecture students are expected to use their experience to develop new ideas and apply this critical thinking process within the context of producing a well-reasoned architectural project [49]. With foundations in experiential learning, these processes provide evidence that real-world experiences can offer opportunities to test, trial, revise and develop a student’s subject knowledge. Direct experience was a crucial component of their understanding.

The activities associated with field trips permit students to engage with the core fabric of buildings, interiors and landscapes and understand the tangible and intangible values that form such fabric. The staged process allowed students to reflect on the values that underpin an experience and associate those with ideas, places and themes. In addition, such experience and emotional response allowed students to fully comprehend the design output and extrapolate concepts and ideas into a coherent design framework for future use. FABRIC (finding, assimilating, being, reflecting, introspecting, and concluding) can provide a framework for enhanced experiential learning for those in the architecture professions, containing both tangible and intangible values (Table 18).

Table 18.

FABRIC Conceptual Framework (adapted from [23,24]).

The potential long-term impact of the pandemic on architecture, landscape architecture, and interior architecture is the subject of ongoing discussion [50]. Many new tools and techniques have been developed and adopted for teaching online and there is an ongoing development of virtual technologies to try to augment the loss due to restrictions on site visits, etc. Virtual field trips have been found to solve many of the issues associated with taking students on excursions, such as the cost, the unsustainability of travel, and the disruption to student course schedules [48,49,50,51,52,53]. Further, advocates of virtual field trips point out the advantages of engagement from reviewers, critics, and jurors from across the country and from abroad [39].

Virtual travel can take students to places that would not be possible in person – hey can go beyond reality [32]. As with photography, advanced technologies can give advanced results including sharper colours, better lighting performance, changes to scale, not to mention increased aesthetic pleasure and seduction, all of which can lead to illusionary results and the potential to serve a broader agenda. For these reasons, the experience of physical space is still essential for architectural education. It is still impossible to match the experience of walking as a means for understanding a place and engaging with its smells, feel, and atmosphere, which are all impossible to replicate authentically.

The second outcome of travel restriction has been an increase in domestic tourism. The restrictions on international travel have resulted in the substitution of international tourists with domestic ones, which means that people are increasingly visiting tier-two cities and searching for local icons of architecture and landscape architecture. Students enjoy field trips, collaboration, and group comradery that help crystallise connections between theory and reality and contribute to enhanced learning. As the density of iconography is reduced in rural or semi-rural settings, more time is available for exploration and a more profound overall experience. These spaces and places are available to students for direct experience, and they also have the added potential of extrapolation. Combining the direct experience of the local with techniques for understanding the global icon can optimise learning outcomes. Emerging questions relate to how architecture should then be evaluated, which forces an interrogation of the word ‘iconic’.

6. Conclusions

Iconic architecture, interior architecture, and landscape architecture are most often understood through photographic media that mediate between the idea and the reality for those learning to design. The drastic lockdown responses to COVID-19 and the limitations on local and international travel highlighted the importance of the visual and the potential of the virtual in understanding architecture. A close examination of iconicity also highlights its relationship to capitalist interests and demonstrates how the visual media can also be understood as a system that goes far beyond a strict representation of the object. In a climate of ‘post truth’ where publicity, politics and perception play ever more crucial roles, and representations of iconic architecture and landscapes increasingly blur the boundaries between the imaginary and the tangible.

This research compared the image of iconic architecture and landscape in four iconic European cities (Paris, Barcelona, Seville and Lisbon) with the physical experience as seen through the eyes of fifty undergraduate and postgraduate architecture, interior architecture and landscape architecture students from New Zealand. It finds that today’s students are savvy and sophisticated consumers of technology and that with appropriate scaffolding, a meaningful alternative experience of buildings, interiors, and landscapes can be provided. For example, students were able to access research in foreign languages using translation software, construct 3D models based on 2D datasets, understand context based on GIS (geographical information systems) modelling of solar, wind and water impacts, and identify photoshopped images. FABRIC is proposed as a conceptual framework for educating design students through experiential learning in times of travel restriction. “We cannot allow ourselves to return to a pre-pandemic ‘normality’ and continue to build the same type of buildings or teach the same syllabi or instruct classes with the same teaching goals.” [54]. By adopting the FABRIC framework, local architecture can be used as a model for understanding international icons through the overarching themes of scale, the experience of space, embodiment and sensory feeling, and visual aesthetics. While “architectural photography is just product photography as no picture can ever successfully emulate the real and truly representation and experience of architecture” [55], the use of this framework can help overcome the potential risks for those in design disciplines, which have been exacerbated through virtual travel in the face of travel restrictions.

We find that an expanded framework for experiential learning is necessary for students researching the built environment, particularly one that emphasises the importance of context, clearly separates the action of reflection from that of introspection, and concludes with applying lessons learned in ongoing creative work. These steps form useful strategies for extending students’ capabilities in thinking creatively as well as developing their confidence. In the face of globalisation, where iconic architecture is a significant part of the contemporary city, its image, and its identity, regional contexts for iconic architecture are replaced by global contexts. Our research also foreshadows a renewed interest in the local and more sub-urban centres for ease of access, for the slowing of experience, and greater ‘authenticity’. A new attention to regionalism can create and sustain identity, considering a more local contextual harmony that represents and respects the character of that place. By using FABRIC as a tool to understanding architecture, interior architecture and landscape directly in their local built environment, students not only learn about how to understand the virtual experience of icons, but they gain a greater sense of stewardship and appreciation for their local ‘place’, one that can foster a heightened responsibility for their surroundings.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.M. and B.M.; methodology, J.M. and B.M.; formal analysis, J.M. and B.M.; investigation, J.M. and B.M.; data curation, J.M. and B.M.; writing—original draft preparation, J.M. and B.M.; writing—review and editing, J.M. and B.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was approved by the Human Ethics Committee of Te Herenga Waka—Victoria University of Wellington and conducted within their ethical guidelines (protocol code 0000020280).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to ethical and privacy restrictions.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Sklair, L. Iconic architecture and urban, national, and global identities. In Cities and Sovereignty: Identity Politics in Urban Spaces; Davis, D., Duren, N., Eds.; Indiana University Press: Bloomington, IN, USA, 2011; pp. 179–195. ISBN 978-0-253-00506-9. [Google Scholar]

- Sklair, L. Iconic architecture in globalizing cities. Int. Crit. Thought 2012, 2, 349–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sklair, L. The Icon Project: Architecture, Cities, and Capitalist Globalization; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2017; ISBN 978-0-19-046418-9. [Google Scholar]

- Berg, P.O.; Kreiner, K. Corporate architecture: Turning physical settings into symbolic resources. In Symbols and Artifacts: Views of the Corporate Landscape; Gagliardi, P., Ed.; de Gruyter: Berlin, Germany, 1990; pp. 41–67. ISBN 978-0-202-30428-1. [Google Scholar]

- Julier, G. Urban Designscapes and the Production of Aesthetic Consent. Urban Stud. 2005, 42, 869–887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barreneche, R.A. New Retail; Phaidon Press: New York, NY, USA, 2008; ISBN 978-0-7148-4862-4. [Google Scholar]

- Ponzini, D. The Values of Starchitecture: Commodification of Architectural Design in Contemporary Cities. Organ. Aesthet. 2014, 3, 10–18. [Google Scholar]

- Lynch, K. The Image of the City; Harvard-MIT Joint Center for Urban Studies Series; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1960; ISBN 978-0-262-62001-7. [Google Scholar]

- Warnaby, G. Rethinking the Visual Communication of the Place Brand: A Contemporary Role for Chorography? In Rethinking Place Branding; Kavaratzis, M., Warnaby, G., Ashworth, G.J., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2015; pp. 175–190. ISBN 978-3-319-12423-0. [Google Scholar]

- Brott, S. The iconic and the critical. In Global Perspectives on Critical Architecture; Hartoonian, G., Ed.; Routledge: Oxfordshire, UK, 2016; pp. 137–150. ISBN 1-315-58496-4. [Google Scholar]

- De Maré, E.S. Photography and Architecture; Praeger: Westport, CT, USA, 1961. [Google Scholar]

- Marques, B.; McIntosh, J. The Spell of the Visual and the Experience of the Sensory: Understanding Icons in the Built Environment. Charrette 2018, 5, 68–77. [Google Scholar]

- Downes, M.; Lange, E. What You See Is Not Always What You Get: A Qualitative, Comparative Analysis of Ex Ante Visualizations with Ex Post Photography of Landscape and Architectural Projects. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2015, 142, 136–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Colomina, B. Le Corbusier and Photography. Assemblage 1987, 4, 6–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Willocks, V. The Image of Architecture: Architectural Photography. In Research Paper; Victoria University of Wellington: Auckland, New Zealand, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Hyun, M.S.; Bafna, S. The Photographic Expression of Architectural Character: Lessons from Ezra Stoller’s Architectural Photography. J. Archit. 2019, 24, 778–802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stierli, M. Architecture and Visual Culture: Some Remarks on an Ongoing Debate. J. Vis. Cult. 2016, 15, 311–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nassauer, J.I. Framing the Landscape in Photographic Simulationt. J. Environ. Manag. 1983, 17, 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Lange, E. The Limits of Realism: Perceptions of Virtual Landscapes. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2001, 54, 163–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meethan, K. Introduction: Narratives of Place and Self. In Tourism, Consumption and Representation: Narratives of Place and Self; Meethan, K., Anderson, A., Miles, S., Eds.; CABI: Oxfordshire, UK, 2006; pp. 1–23. ISBN 1-84593-164-5. [Google Scholar]

- Soberg, M. Theorizing the Image of Architecture: Thomas Ruff’s Photographs of the Buildings of Mies van Der Rohe. In Proceedings of the 2008 Conference Architectural Inquiries, Gothenburg, Sweden, 25 April 2008; Chalmers University of Technology: Gothenburg, Sweden, 2008; pp. 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- DeWitt, J.; Storksdieck, M. A Short Review of School Field Trips: Key Findings from the Past and Implications for the Future. Visit. Stud. 2008, 11, 181–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kolb, D.A. Experiential Learning: Experience as the Source of Learning and Development; Pearson Education: Upper Saddle River, NJ, USA, 1984; ISBN 978-0-13-295261-3. [Google Scholar]

- Krakowka, A.R. Field Trips as Valuable Learning Experiences in Geography Courses. J. Geogr. 2012, 111, 236–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radder, L.; Han, X. An Examination Of The Museum Experience Based On Pine And Gilmore’s Experience Economy Realms. JABR 2015, 31, 455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Healey, M.; Jenkins, A. Kolb’s Experiential Learning Theory and Its Application in Geography in Higher Education. J. Geogr. 2000, 99, 185–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Cassady, J.C.; Kozlowski, A.; Kornmann, M. Electronic Field Trips as Interactive Learning Events: Promoting Student Learning at a Distance. J. Interact. Learn. Res. 2008, 19, 439–454. [Google Scholar]

- Klein, P. Active Learning Strategies and Assessment in World Geography Classes. J. Geogr. 2003, 102, 146–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cornell, R.M.; Johnson, C.B.; Schwartz, W.C., Jr. Enhancing Student Experiential Learning with Structured Interviews. J. Educ. Bus. 2013, 88, 136–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jose, S.; Patrick, P.G.; Moseley, C. Experiential Learning Theory: The Importance of Outdoor Classrooms in Environmental Education. Int. J. Sci. Educ. Part B 2017, 7, 269–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ernst, C.M.; Buddle, C.M.; Soluk, L. The Value of Introducing Natural History Field Research into Undergraduate Curricula: A Case Study. Biosci. Educ. 2014, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehmet, K.; Kukul, V.; Çakir, R. Conceptions and Misconceptions of Instructors Pertaining to Their Roles and Competencies in Distance Education: A Qualitative Case Study. Particip. Educ. Res. 2018, 5, 67–79. [Google Scholar]

- Pine, B.J.; Gilmore, J.H. The Experience Economy: Work Is Theatre & Every Business a Stage; Goods & Services are No Longer Enough; Harvard Business School Press: Boston, MA, USA, 1999; ISBN 978-0-87584-819-8. [Google Scholar]

- Thompson, J.J.; Conaway, E.; Dolan, E.L. Undergraduate Students’ Development of Social, Cultural, and Human Capital in a Networked Research Experience. Cult. Stud. Sci. Educ. 2016, 11, 959–990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, J.A.; Jarman, M.; Osborn, M. Doing Interpretative Phenomenological Analysis. In Qualitative Health Psychology: Theories and Methods; Behaviour and Health Series; Murray, M., Chamberlain, K., Eds.; SAGE Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 1999; pp. 218–240. ISBN 978-0-7619-5661-7. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, J.A.; Flowers, P.; Larkin, M. Interpretative Phenomenological Analysis: Theory, Method and Research; SAGE Publications: London, UK, 2009; ISBN 978-1-4462-4325-1. [Google Scholar]

- Attride-Stirling, J. Thematic Networks: An Analytic Tool for Qualitative Research. Qual. Res. 2001, 1, 385–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Using Thematic Analysis in Psychology. Qual. Res. Psychol. 2006, 3, 77–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Klippel, A.; Zhao, J.; Oprean, D.; Wallgrün, J.O.; Chang, J.S.-K. Research Framework for Immersive Virtual Field Trips; IEEE: Osaka, Japan, 2019; pp. 1612–1617. [Google Scholar]

- Jones, P.B. The Photo-dependent, the Photogenic and the Unphotographable: How our Understanding of the Modern Movement has been Conditioned by Photography. In Camera Constructs: Photography, Architecture and the Modern City; Higgott, A., Wray, T., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK, 2016; pp. 69–82. ISBN 1-315-26092-1. [Google Scholar]

- Connah, R. How Architecture Got Its Hump; Preston Thomas Memorial Lecture Series; Department of Architecture, C.U., Ithaca, New York, Ed.; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2001; ISBN 978-0-262-53188-7. [Google Scholar]

- Marques, B.; Freeman, C.; Carter, L.; Pedersen Zari, M. Sense of Place and Belonging in Developing Culturally Appropriate Therapeutic Environments: A Review. Societies 2020, 10, 83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montello, D.R. A New Framework for Understanding the Acquisition of Spatial Knowledge in Large-Scale Environments. Spat. Temporal Reason. Geogr. Inf. Syst. 1998, 143–154. [Google Scholar]

- Kristianova, K.; Joklova, V. Education by Research in Urban Design Studio. In Proceedings of the EDULEARN17 9th International Conference on Education and New Learning Technologies, Barcelona, Spain, 3–5 July 2017; International Academy of Technology, Education and Development (IATED): Barcelona, Spain, 2017; pp. 2691–2694. [Google Scholar]

- Böhme, G.; Thibaud, J.-P. The Aesthetics of Atmospheres; Routledge: London, UK, 2016; ISBN 1-315-53818-0. [Google Scholar]

- Petrović, E.K.; Marques, B.; Perkins, N.; Marriage, G. Phenomenology in Spatial Design Disciplines: Could it Offer a Bridge to Sustainability? In Advancements in the Philosophy of Design; Vermaas, P.E., Vial, S., Eds.; Design Research Foundations; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2018; pp. 285–316. ISBN 978-3-319-73301-2. [Google Scholar]

- Sloterdijk, P. Mobilization of the Planet from the Spirit of Self-Intensification. Drama Rev. 2006, 50, 36–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zumthor, P. Atmosphères, Environnements Architecturaux-Ce Qui m’entoure; Birkhäuser: Basel, Switzerland, 2008; ISBN 978-3-7643-8841-6. [Google Scholar]

- Marques, B.; McIntosh, J.; Campays, P. Creative Design Studios: Converting Vulnerability into Creative Intensity. Int. J. Innov. Educ. 2021, 7, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Architecture Deans on How COVID-19 Will Impact Architecture Education. 2020. Archinect. Available online: https://archinect.com/features/article/150195369/architecture-deans-on-how-covid-19-will-impact-architecture-education (accessed on 17 July 2021).

- Jaselskis, E.J.; Jahren, C.T.; Jewell, P.G.; Floyd, E.; Becker, T.C. Virtual Construction Project Field Trips Using Remote Classroom Technology; Ruwanpura, J., Mohamed, Y., Lee, S.-H., Eds.; American Society of Civil Engineers: Banff, AB, Canada, 2010; pp. 236–245. [Google Scholar]

- Klemm, E.B.; Tuthill, G. Virtual Field Trips: Best Practices. Int. J. Instr. Media 2003, 30, 177. [Google Scholar]

- Tuthill, G.; Klemm, E.B. Virtual Field Trips: Alternatives to Actual Field Trips. Int. J. Instr. Media 2002, 29, 453. [Google Scholar]

- Papu, S.; Pal, S. Braced for Impact: Architectural Praxis in a Post-Pandemic Society. Available online: https://advance.sagepub.com/articles/preprint/Braced_for_Impact_Architectural_Praxis_in_a_Post-Pandemic_Society/12196959 (accessed on 6 January 2021).

- Bergera, I. Photography and Modern Architecture in Spain: Focusing the Gaze. In Proceedings of the Photography and Modern Architecture Conference Proceedings, Porto, Portugal, 22–24 April 2015; Trevisan, A., Maia, M.H., Moreira, C.M., Eds.; University of Porto: Porto, Portugal, 2015; pp. 30–43. [Google Scholar]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).