Abstract

After five years of research on microplastic pollution of soils it becomes obvious that soil systems act as a reservoir for microplastics on global scales. Nevertheless, the exact role of soils within global microplastic cycles, plastic fluxes within soils and environmental consequences are so far only partly understood. Against the background of a global environmental plastic pollution, the spatial reference, spatial levels, sampling approaches and documentation practices of soil context data becomes important. Within this review, we therefore evaluate the availability of spatial MP soil data on a global scale through the application of a questionnaire applied to 35 case studies on microplastics in soils published since 2016. We found that the global database on microplastics in soils is mainly limited to agricultural used topsoils in Central Europe and China. Data on major global areas and soil regions are missing, leading to a limited understanding of soils plastic pollution. Furthermore, we found that open data handling, geospatial data and documentation of basic soil information are underrepresented, which hinders further understanding of global plastic fluxes in soils. Out of this context, we give recommendations for spatial reference and soil context data collection, access and combination with soil microplastic data, to work towards a global and free soil microplastic data hub.

1. Introduction

During the last decade it becomes obvious that plastics have reached almost every ecosystem worldwide. This global pollution is mainly triggered through the uncontrolled release of plastics to the environment during all stages of the plastic value chain [1] and contributes to the exceedance of planetary boundaries [2]. The Global plastic pollution is thereby a comparatively young phenomenon, as the majority of human-made polymers or polymeric substances have been developed within the early 20th century followed by an exponential global plastic production increase since the late 1950s [3,4]. Within the last seven decades plastics have become the most common, every-day life product that humans use within all areas of life [4]. Nevertheless, beside numerous benefits regarding material properties (low-cost, lightweight) and variety (most versatile applicability), plastics have turned to environmental contaminants with global impacts [1].

Plastics in general, but more often plastic particles defined through their size like macroplastics (>5 mm), microplastics (MP, 5000–1 µm) or nanoplastics (<1 µm) have been discovered in marine environments, freshwaters, terrestrial and atmospheric systems [2,3,5,6]. In terrestrial systems with a focus on soils, a first study on synthetic fibers was published in 2005 [5] followed by a first study on MPs by Fuller and Gautam in 2016 [6], even if plastics have been documented before as anthropogenic artefacts in soils description or archeological science [7].

After the first scientific records of plastics and MPs in soils, it becomes more obvious that soils can act as both sink and sources for plastics in the environment. [6,8]. Between 2016 and 2021 the number of studies dealing with plastic or MP pollution of soils increased from three records in 2017 up to 218 records in 2021 according Web of Science hits (Clarivate Analytics) [9]. During this time period publications were published that (a) develop analytical methods for quantification and characterization of plastics in soils [10,11,12]; (b) proof the presence of macro-, micro- and nanoplastics in soils combined with quantification and characterization of the plastics [9]; (c) identify different sources of soils plastic pollution [7]; (d) investigate soils internal processes like plastic aging or the transport of plastics in soils; (e) discover various consequences of soils plastics including impacts on soil properties, matter fluxes, soil organisms and plants [7,13,14,15]. First modelling approaches have been conducted, for example, to model possible inputs of plastics into agricultural soils on nationwide scales [10]. Within these key areas of soil related plastic research, the quantification of plastics in different soils, soil regions and soilscapes under different land uses plays an important role. First, in order to understand the extent of soil pollution with plastics, and second to collect basic data on plastic occurrences in the soil environment.

From a soil geography point of view, soils as the object of study and regarded as a potential reservoir for plastics should be understood as a three-dimensional, spatial phenomenon and therefore one of the environmental spheres crossed by plastics during global plastic transport cycles [7]. Soils occur at local sites with distinct characteristics caused by soil forming factors (climate, bedrock, anthropogenic activity) [11,12]. This local distribution of soils connects on a wider spatial perspective to a landscape perspective [12]. Therefore, soils can be related to a “soilscape” from a landscape-oriented research perspective, covering spatial extensions from local to regional or global scales [12].

With regard to the global plastic pollution, which could be defined as an environmental systems and spatial scales overreaching phenomenon [13], terrestrial environments and especially soils build a key link between the atmosphere, lithosphere, hydrosphere, biosphere and anthroposphere for MP fluxes. Thus, it is necessary to investigate the plastic pollution of soils with a profound spatial reference and work towards a global database of MPs in soils. As recent plastic research shifts towards the environmental modelling of plastic fluxes or plastic concentrations, as already applied for other environmental contaminants within an ecotoxicological context [14], those database become even more important.

From this background, this review aims to trace the spatial reference and soil context data provided by case studies dealing with plastics in different soilscapes. Summarized information on MP types and concentrations, polymeric composition and effects are available within recent reviews [8]. Instead of those information, we focused on soil data and land use as a local plastic source in our review, as those are directly linked to soilscape attributes like climate, topography and soil formation. Additionally, this review was led by the question on how soil geography with its common understanding of soils and documentation practices can help to combat the MP pollution of soils.

Based on a questionnaire applied to each study considered, this review follows the following objectives:

- Analyze the spatial reference reported as well as the primary land uses and landscapes where MP studies have been conducted on different spatial levels.

- Identify current trends and potential gaps in the documentation of spatial reference, soil context information.

- Derive recommendations for improved spatial reference within future research and work towards a global database of MPs in soils.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Data Collection

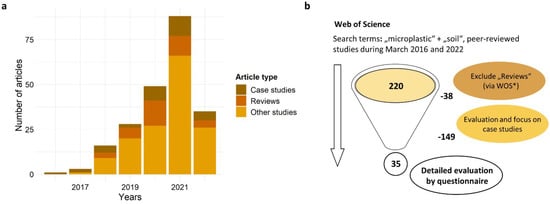

The search and selection of studies was conducted with the Web of Science (WOS) [9] database (Clarivate Analytics) by the combination of the search terms “microplastic” + “soil” for the period January 2016–March 2022 (Figure 1). The searched studies were further refined to peer-reviewed studies, resulting in 220 research articles for the respective time period. From this initial selection, review papers were excluded via WOS refinement, resulting in a reduction of 38 articles. Furthermore, own research conducted by C.J. Weber (Weber and Opp 2020, Weber et al. 2021, Weber et al. 2022) on MPs in soils was excluded, to keep an objective evaluation during data curation and analysis. The work of Scheurer and Bigalke (2018) has been retained as it can be considered as one of the few studies from the early publication phase of soil MP research. Finally, all remaining articles were evaluated via title, keywords and abstract and narrowed to studies with a clear focus on MPs detection in soils (case studies). Therefore, any laboratory experiments or studies under controlled conditions were excluded from further evaluation, resulting in a total number of 35 studies for detailed evaluation.

Figure 1.

Trend in the number of studies on MPs in soils and process of study selection: (a) Number of articles identified with the search terms “microplastic” + “soil” for the period January 2016–March 2022 via WOS database (Other studies include laboratory experiments and studies under controlled conditions). (b) Outline of study selection and respective criteria.

2.2. Data Evaluation

Each of the selected articles was evaluated with the help of a previously defined questionnaire (Table 1) which we applied on the selected studies during data evaluation. The questionnaire is composed of questions on the following general topics: (1) Basic data, including general article information like title and object identifier (DOI); (2) Spatial reference and study area data, including information on study areas, coordinates or study area map availability; (3) Sampling data, including questions about the number of soil samples, sampling depth documentation or systematic sampling; (4) Soil context data, including questions about land use or soil type documentations; (5) Data handling, including questions about open data handling and the availability of sampling locations or analysis results.

Table 1.

Questionnaire applied to each study and possible responses. Full dataset available: https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.20059022, accessed on 14 July 2022.

Within the questionnaire results were analyzed in the form of the following responses (Table 1, Table S1): (1) Yes-No questions which query the existence of respective information; (2) Categorized questions which query given information within question-based categories (e.g., sampling according to soil horizons or depths); (3) Value questions which query values or names of given information (e.g., Country name or number of soil samples analyzed). In the case of non-answerable questions or the general missing of asked information, questions have been answered with “not available” (na). Additional definitions of some asked questions or categorized answers are given in Table S1.

The obtained results were further spatially illustrated on a global scale with the help of QGIS (QGIS.org, 2022: https://www.qgis.org/, accessed on 15 January 2022) based on number of studies per country. Data management and illustration was conducted with the help of Microsoft Excel 2021 (Microsoft), and R (R Core Team, 2020), using RStudio (Version 3.4.1; RStudio Inc., Bosten, MA, USA) and ggplot2 package (Wickham, 2016: https://ggplot2.tidyverse.org, accessed on 6 January 2022).

3. Spatial Reference of Soil Related Microplastic Research

3.1. Global Evidence of Microplastics in Soils and Data Availabiltiy

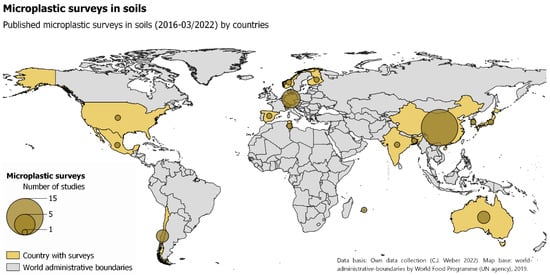

Most studies today were conducted in the northern hemisphere and in individual countries (Figure 2). The majority of these are located in Central Europe and China (Table 2). In general, each study evaluated has stated the country were the study or sampling was conducted.

Figure 2.

Worldwide map of existing (as of March 2022) studies reporting (micro-)plastic evidence in soils.

Table 2.

Evaluated studies and their respective country of implementation as well as region and reference data.

The finding that initial research within an emerging research field like MPs in soils is carried out primarily in high-income and research-intensive countries in the global north (Figure 2) is not new [50]. With the exception that only very few data is available for the United States and Canada, which belong clearly to the global north, the widespread underrepresentation of the so-called “global south” was already reported for MP research on freshwater systems [51]. This underrepresentation could be traced back to a strongly limited accessibility of research data, scientific findings and applied analytical methods. Only 11.4% of the evaluated studies followed an open data principle and have made their research data accessible without charge in scientific repositories or Supplementary Materials (SI) (Table 3). Furthermore, the majority of evaluated studies have not been published in open access journals, which limits the access to those scientific findings for low-income regions.

Table 3.

Response data given in % on Yes-No questions from evaluated (n = 35) publications.

Even if research about atmospheric MP deposition, MPs in aquatic systems also at very remote locations implies a global distribution of MPs, we have basically no idea about the concentrations, compositions, size distributions or other features of MPs in most parts of the world. This might be relevant as input sources and fluxes might substantially differ between climate zones, soilscapes or countries. Rather, a detection of MPs in different soils can be noted, which is spatially incoherent and isolated, with a clear focus in the northern hemisphere and single countries (Figure 2).

3.2. Spatial Recovery and Study Area Extensions

The term “spatial recovery” means the spatial traceability of the study sites. This recovery strongly depends on the availability of information about the sampled regions, areas or single sampling points. In general, most of the evaluated studies investigated not only single locations (e.g., a single agricultural field; Table S1) but rather different locations across different scales like urban environments (e.g., [17]), regions (e.g., [30]) or nations (e.g., [19]) (Table 3).

Only 22.9% of the evaluated studies provided geographic coordinates (Table 3) and only one study provides a free available geodata dataset (e.g., .kml-file) [47]. Other studies provide maps (48.6% of evaluated studies), partly in combination with coordinates (27.8% of studies with maps) (Table 3). The maps usually contain information about the sampling points or area locations and in some cases also geographical coordinates at the edge of the map (e.g., [26]). Those coordinates enable a more precise spatial orientation of the studied areas, but do not provide a precise information about the exact sampling locations.

The published maps use different background information, such as administrative boundaries (e.g., [17]), aerial photographs (e.g., [42]) or digital terrain models (e.g., [38]) from different sources, or the presentation of sketches (river course and urban areas) (e.g., [28]). Likewise, some of the data presented are very different. Thus, the illustrations range from simple sampling points with labels (e.g., [30]), to the presentation of results (e.g., mean plastic content) (e.g., [40]), to combined presentations of up to three factors (e.g., position of the sites, plastic content, and one additional information item) (e.g., [19]).

3.3. Soil Sampling Information

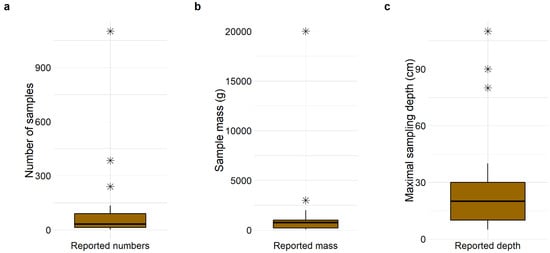

The documentation of the sampled soil mass (in g−1 or kg−1) or volume (ml−1 or L−1) is important to compare sampling concepts among each other and to be able to provide particle- or mass-based results (plastic particles per kg−1 or plastic mass in mg per kg−1) [52,53]. 57.1% of the evaluated studies document the sample mass or volume (Table 3) and the total number of analyzed samples or the number can be calculated from information given. On average each study has sampled and analyzed 93.5 soil samples on average (median 33 soil samples) in a range of 2–1100 samples, including replicates [43,45] (Figure 3a). Out of the 57.1% of studies which document sample mass the average mass was 2232 g of soil (median 1000 g soil) within a range of 50–20000 g of soil [16,29] (Figure 3b). Despite sample mass, volumes like dm3 [28] or L−1 [49] have been reported but here the documentation is very inconsistent, as only average (e.g., [26]) or maximum values [49] instead of the real volumes per sample are given.

Figure 3.

Documentation of sample numbers, sample mass and sampling depth within the evaluated (n = 35) publications: (a) Absolute number of samples reported (Table 1, 3-1). (b) Exact mass of samples (Table 1, 3-3) documented (data in volumes excluded). (c) Maximal depth of sampling (Table 1, 3-5) documented. Outliers displayed with star (*).

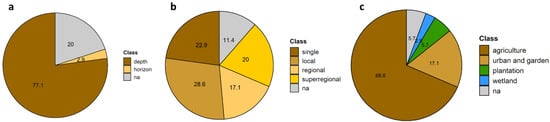

Furthermore, the documentation of sampling depth and the type of soil sampling becomes important in order to evaluate the total mass of MPs in soils if considering the whole soil column as a plastic reservoir or to gain further knowledge about MPs spatial distribution and MP fluxes in soils. Regarding the general documentation of sampling depth, the majority of evaluated studies (77.1%) documented a metric value given in cm below soil surface (Table 3). Likewise, most studies have conducted a depth sampling according metric depths (77.1%), a single study according soil horizons, while 20.0% do not provide any depth documentation (Figure 4a). Only the study of Müller et al. (2022) has performed a sampling based on distinguishable topsoil horizons (A horizons, roadside grasslands) with maximum sampling depths of 20 cm. The mostly performed sampling according to fixed levels (metric subdivision) can also be attributed to the mostly low sampling depths (Figure 3c). The average maximum sampling depth within the evaluated studies was 27.9 cm below soil surface within the range of 5–110 cm. Since 2020 where the average sampling depth was 10 cm, deeper soil layers were increasingly sampled, but still with a strong focus on topsoil [52,54]. Even if the early study on synthetic fibers in sludge effected soils analyzed samples from deeper soil layers (max. 50 cm) in the US [5], sampling of subsoil horizons and MP analyzes was conducted only by Tagg et al. (2022) within agricultural soils according three metric depth intervals (30 cm) in Germany, Hu et al. (2021) within agricultural soils according two metric depth intervals (0–30 cm, 30–80 cm) in China, Cao et al. (2021) within agricultural soils in the Yangtze river floodplain according four fixed depth intervals (20 cm) and Lechthaler et al. (2021) within floodplain soils of Inde river according fixed depth intervals (10 cm) in Germany [28,33,37,44]. Global knowledge on MPs in subsoils is therefore limited to four records in China and Germany, which leads to the fact that total MP contents in soils cannot be determined.

Figure 4.

Documentation of depth sampling, lateral sampling scale and land use within the evaluated (n = 35) publications: (a) Depth sampling according soil horizons or metric depth scales (Table 1, 3-6) about the availability of the documentation (3-2). (b) Spatial scale of lateral sampling (Table 1, 3-8). (c) Major land use types documented (Table 1, 4-2).

Finally, besides the documentation of sample mass and depth specifications, the lateral sampling context becomes important with regard to the spatial representativeness of soil sampling within the studied soilscapes. Whereas 65.7% of the evaluated studies document the lateral sampling procedure, 34.3% do not provide specific information (Table 3). Lateral sampling concepts include for example: (a) one-dimensional approaches (sampling of isolated, single soil columns); or two-dimensional approaches like the sampling of randomized soils (e.g., [15,29]) or according grids (multiple soils) within a respective spatial border (administrative unit, field borders) (e.g., [18]) or sampling of soils along a natural shapes or metric transects (rivers or roads) (e.g., [34,55]). Overall, systematic sampling approaches like purposed by Möller et al. (2020) following systematic approaches, like the sampling of grids (equal spatial dimensions between sampling points) and transects as well as previous defined criteria, account for only 22.9% of evaluated studies (Table 3) [7,52]. Numerical simulation approaches to determine representative sample numbers and volumes, as well as the recommended approach of taking multiple replicate samples within narrow spatial areas [55], are so far underrepresented. Thereby, the approach taken by each study depends not only on the question posed, but also on the spatial and lateral scale of the study. Figure 4b illustrates that just over half evaluated studies consider single (22.9%) or local (28.6) lateral sampling scales, which together cover a confident spatial extension. In contrast to studies with a broader lateral context (regional studies or superregional studies which capture soils across entire landscapes or nations), have been conducted in 37.1% of the evaluated studies. Thus, studies that examine a narrower spatial setting slightly predominate, whereas plastic monitoring on larger spatial scales (oriented towards political spatial units) are underrepresented, and do not allow any conclusions about soils plastic pollution comparing countries or landscape settings.

3.4. Soil Context

Soil context data refers to environmental data that is not directly related to the sampling and analysis of MPs. However, information on land use at sampling sites, the soil itself, especially its name or additional analyses of soil properties are important spatial contexts for the comparison of gained results. For instance, the current land use can provide information on potential MP sources and thus allow conclusions on inputs and mitigation measures, while the soil name and classification hold the most important information of soil properties and formation, which influence MP fluxes in the soil.

The current land use at sampling site is one of the soil related environmental features that has been documented most widely (94.3%) (Table 3). The majority of evaluated studies has conducted sampling on soils under an agricultural land use like cropland (57.1%), special cultures (11.4%) like cotton fields [37] or greenhouse farming [36] and house gardens (5.7%) [16] (Figure 4c). Furthermore, sampling was conducted within urban characterized locations including industrial and municipal complexes [48,53] or plantations [52] and wetlands [25,32]. Remarkable is the absence of studies dealing with forest soils or shrub landscapes, while those uses cover up 37% (forests) and 11% (shrubs) of the global land area [25].

In contrast to the land use documentation, only 20.0% of all evaluated studies reported information on the soil type and its classification according international or national standards (Table 3). This means, that fundamental information on MPs in soils are missing, as the simple, short and comparable name of a soil provides basic information about its properties, soil forming factors [51], which are relevant for the interpretation of MPs fixation and mobility in soils. Therefore, current MP data can only be assigned to the following soil types according to WRB (2015): Entic Haploxerolls [21], Fluvisols [28], Latosols [38] and Haplic-Stagnic Anthrosols [42]. Within a wider spatial context (major soil type of study area regions) the following soil types can be assigned: Entisols [18,47], Vertisols [18], Nitisols [20] and Gleysols [20]. However, some studies indicate soil features like overall texture composition or soil moisture (e.g., [37]) instead of soil classifications. Related to soil features, 40.0% of the evaluated studies conducted additional analysis of soil properties like texture analysis [19,33,41], soil pH [23,33,38,41,47], bulk density [47], moisture [23,38,47], SOM contents [33,41], cation exchange capacity [33], carbon contents [23,47], nitrogen contents [47] and other elemental concentrations [24,34,47].

4. Implications

While comparing the evaluated data from 35 case studies on MPs in soils on a global scale, it becomes obvious that global evidence of MPs in soils is only conditionally present. Although the number of studies has increased significantly since 2019 [52,54], there is an uneven spatial distribution with clear focal points. After about five years of MP research in soils, the global evidence of MPs in soils, also summarized by Büks and Kaupenjohannis (2020, [8]), is strongly limited in contrast to the marine environment [56] or freshwater systems [51]. However, three-dimensional spatial data on MPs in soils, covering widespread land uses and soil formations, is urgently needed to access (1) the dimensions of plastic pollution in soils; (2) enable modelling approaches for the identification of MPs pollution hotspots and critical concentrations; (3) enhance understanding of MPs sources and mitigate MP inputs; (4) track global migration and dissemination of MPs; (5) monitor future developments with regard to risk assessments as well as potential decontamination and restoration measures [6]. With regard to a global plastic pollution, the necessary data should be gained globally, which makes it essential to integrate basic knowledge and research funding within the so-called “global south” [50] and work towards an open data practice to enable global integration of knowledge and research approaches from different environments [57].

In order to strengthen the networking of future research on MPs in soils on a global level, to enable data and result comparisons, and to push forward spatial modeling approaches in the future, a spatial recovery of data is particularly necessary. The evaluated studies covering different soils and soilscapes on different spatial scales, which can only be assessed with exact geographic coordinates. However, these are only available in small numbers, which illustrates the need for better documentation of the spatial settings. Even if maps provide important impressions of lateral sampling contexts and local MP sources, they do not serve as a means of spatial retrieval. Spatial recovery can thereby be easily reached, when each field sampling point is calibrated via global positioning system (GPS) and geospatial data becomes freely available, either via coordinates or geodata in common data formats, like .kml, .shp or .txt files (Table S2). Furthermore, an open spatial database, like already existing for community macroplastic records on land (https://openlittermap.com/, accessed on 14 July 2022) or plastic records in marine and aquatic systems (https://litterbase.awi.de/litter, accessed on 14 July 2022), can be strongly recommended for global plastic records in soils.

With regard to soils as the environmental sphere sampled and studied, the documentation and information of sampling procedures should be good professional practice. Based on the evaluated studies, it can be summarized that actually, a basic documentation of required sampling information is usually available.

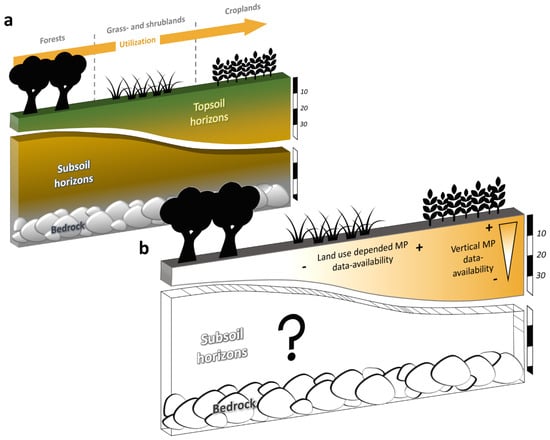

In comparison of all evaluated studies, it could be illustrated that a clear focus on topsoil sampling and therefore topsoil data still exists in comparison to earlier reviews dealing with the topic of soil sampling for MP analyses [7,52,54]. Hence, it becomes clear that data on subsoils is particularly lacking, which, should therefore be increasingly investigated in the future against the background of MP fluxes in the soil, as well as discharges from the soil, to ground- or freshwater systems [58] (Figure 5). This topic becomes particularly relevant if discussing the sink and/or source function of soils for MPs, as current research focusses mainly on soils as MP sinks or reservoirs, but often negated soils as MP sources for the environment through erosion processes [59] or groundwater fluxes [60]. Additionally, these data are necessary in connection with spatial reference data, to gain a further understanding of global MP flows through the environment, considering soils as one of several environmental spheres crossed by MPs.

Figure 5.

Simplified three-dimensional landscape model: (a) Model displaying major land use forms and utilization intensity as well as topsoil-subsoil-bedrock boundaries. (b) Model displaying the current knowledge and data-intensity of microplastics in soils.

Furthermore, it could be determined that vertical soil sampling was conducted strong predominantly according to metric levels, while horizon-based sampling and a consideration of pedogenic features is missing. In this case, it becomes clear that although the use of metric subdivisions provides better comparability, the influences of pedogenic characteristics and processes are difficult to incorporate into the interpretation of the data. The basic documentation of sampling information also includes information on the lateral sampling procedure, like the selection of considered soil depths, it is strongly question oriented [52] how a lateral sampling concept becomes structured. While basic information was mostly available within the evaluated studies, systematic lateral sampling approaches with a maximum possible representativeness for the spatial scale considered, should be featured in future. New insights on MPs behavior within soil environments as well as the inclusion of soils as a part of global plastic transport processes, makes it necessary to further expand systematic sampling approaches.

Furthermore, it seems that MPs in soils have been considered quite isolated so far. With regard to soil context data, only the documentation of soils land use seems to be a good professional practice to date. Nevertheless, it could be evaluated that the investigation of agricultural utilized soils, including cropland, farmlands as well as special cultures, accounts for the majority of studies to date. As agricultural land use makes up around 50% of global habitable land area (104 million km2) [60], the data basis on MPs in agricultural soils with a clear focus on croplands is the strongest so far. However, croplands in Europe or China differ from those in Africa or South America, leading to the fact, that no assumptions can be driven for countries which have no studies so far. Furthermore, MP data of soils under other dominant land uses like forests (39 million km2) or shrubs (12 million km2) as well as farmed grasslands (40 million km2) are completely missing so far [60]. However, even these land uses are important to enable an access of the total soil pollution and to gain basic knowledge of MPs background contents also in less anthropogenic effected landscapes (e.g., forests), where only atmospheric MP depositions acts as a major source. To fill this gaps in future, sampling should be carried out in previously unexploited areas, which would promote a better understanding of global MP dissemination in soils. Regarding the global scale of plastic pollution, a first global sampling approaches could be oriented to dominant soils and their land uses of each continent, following a randomized sampling of full, three-dimensional soil columns within each dominant soilscape unit. As climate is a key feature for soil formation and subsequent land use, therefore effecting principal soil features the influence MP fixation or fluxes, but also local MP sources, global sampling concepts should also consider comparisons between major climate zones.

The isolated consideration of MPs in soils becomes highlighted by the missing of fundamental soil description within the majority of evaluated studies. The missing of simple information like soil type according international standards leads to a very limited understanding of the soil context and its influence on MPs. In line with the so far few or non-recorded areas of the earth, MP evidence is also lacking in the associated soil regions and typical soils (e.g., Ferrasols, Calcisols, Histosols or Chernozems) [61].

However, there are different ways to add basic soil context data in future studies, based on professional or easy access ways. As recommended in Table S2, current land use as a necessary data can be documented through easy field observation. Additional land use data, like the land use practice on croplands, important for MP sources, can be accessed by land owner interviews or land use changes, important for the detection of past MP sources, can be accessed via global land use change datasets (e.g., via Copernicus Global Land Service providing land cover data on a 100 m resolution) (Table S2). Fundamental information on soil types sampled, which provides a unique description of soils and their effects on MP retention and mobility, can be accessed by full soil descriptions or by the use of global to local soil datasets, mostly provided by the FAO via “Legacy Soil Maps and Soils Databases” (Table S2). In this way, even non-soil scientists can provide information on the soil types and their properties from maps and survey data.

Finally, it could be summarized with regard to soil context data, that the additional analysis of different soil features is so-far strongly question oriented or hypothesis depended. Despite the recommendation of strongly necessary data like spatial recovery data (coordinates), and soil context data (land use and soil type), beneficial data on physical soil properties, especially soil textures, soil pH and soil organic matter (SOM) contents could be recommended, as each of those properties will affect MP fluxes in the soil [58] (Table S2). For example, clay content within soil textures gives a first implications of the availability of clay minerals, which might impact MP fixation to clay minerals or in soil microaggregates. As a further example, the soil pH will affect the presence of earthworms in the soil and thus strongly influence the biogenic activity including microbiological effects on MPs, while texture and SOM will have a strong influence on soil pore structure and thus affect the abiotic depth transport in soils [5,62]. The aging of MP in soils might depend on soil microbiota [63,64] and the consequences of MP to the soil structure, soil organisms and plants [65,66,67] might strongly depend on the above mentioned soil properties. Thus, reporting this data together with the MP data might enable a much wider use and application of the data for later modelling and meta-analysis. Each of the mentioned parameters can be recorded via field and laboratory methods for each sampled soil, but can also be accessed with some spatial inaccuracy via the “WISE–Global Soil Profile data” or the “SoilGrids” application provided by the “International Soil Reference and Information Centre” (Table S2).

Finally, the assessment of spatio-temporal MP dynamics in soils needs a holistic data base which, in addition to necessary spatial reference and soil context data, also includes pedogenetic and physical-chemical soil data in a beneficial manner [68,69]. Nevertheless, the main challenge in the coming period will involve maximizing the use of existing and new soil related MP data. If spatial reference data, soil context data and MP analysis results becomes clearly linked in datasets, those geospatial soil MP data becomes a strong tool in the future. For those datasets we recommend an open data policy and data sharing in a beneficial way, using free, long-term persistent data repositories with stable identifiers (DOI) and support open licenses like “figshare” (https://figshare.com/, accessed on 14 July 2022), “Open Science Framework” (https://osf.io, accessed on 14 July 2022) or “EarthChem” (https://www.earthchem.org/, accessed on 14 July 2022), among others. Useful keywords for easy retrieval of soil related datasets, could be the combination of “microplastic” or in case of other plastic size focusses “macroplastics” or “nanoplastics” with the fixed term “soil data hub” and an additional spatial identifier following a “Continent-Country-Region/landscape” style (e.g., “Europe-Germany-Central_German_low_mountain_range). Besides the use of existing repositories, a centralized global soil data hub would be suitable to link existing and further soil related MP (geo)data in in the style of an online portal combining repository functions and interactive map view.

5. Conclusions

Case studies on MP abundance within different soils have been conducted spatially isolated, with a focus on agricultural soils and topsoils. Current research provides information on sampling procedures as well as land use, while spatial reference or soil context data are often lacking. In conclusion it can therefore be stated, that the limitations of spatial representativeness, limited access to spatial reference and related soil data within a global context, build the major gap within the framework of the current state of research.

From this context and in a perspective way, the plastic pollution of soils should be understood as one part of a global crisis. The polluted soils itself, should be regarded as a spatial sphere acting as a temporary reservoir for MPs and an environmental system passed by plastics within global transport cycles, acting therefore also as a source for MPs. If considering this way of understanding, it becomes necessary to study soils MP with a combination of fundamental soil description including soil formation, specific features and pedogenic processes. So far, the evaluation and understanding of environmental risks posed by MP pollution in soils, is still in its infancy. Nevertheless, soil geography and its basic understanding of soils as well as soil related geographic information can help to understand and mitigate MP pollution in future.

In order to promote soil geographic and soil scientific approaches onto a more comprehensive, comparable and holistic global database on MPs abundance within soils, the following recommendations can be highlighted:

- Further advancement of monitoring programs, with a clear recommendation to political stakeholders to establish national monitoring programs on MPs in soils. With the background of proven as well as assumed environmental risks posed by MPs to soils, further data collection and the designation of potential MP hotspots becomes essential.

- Expand documentation of sampling procedures, spatially representative and systematic approaches in combination with the provision of basic soil information (soil classification) made freely available with an easily accessible spatial reference provided through open geodata.

- Increased investigation of subsoils for the presence of MP as well as the consideration of pedogenic soil features during sampling and later analysis, especially with regard to MP dynamics (e.g., MP entry pathways, in situ relocations and leaching) in soils.

- A new focus on previously unexplored soil regions and soil types in conjunction with so far less considered land uses, in order to gain further insight into global distribution pathways of MPs in soils and to reveal so far unknown impacts on global important soilscapes.

Soil geographic approaches will help to understand MP pollution of soils, if a global, representative and appropriate data basis becomes available. Spatial modelling approaches will be a strong tool to tackle further and maybe still unknown challenges for soil environments, if once such a data basis has been achieved.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/microplastics1040042/s1, Table S1: Definitions of selected questions and for categorized responses from the applied questionnaire; Table S2: Recommendation on basic spatial positioning and soil data for MP research together with easy access pathways and global dataset examples.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, C.J.W. and M.B.; Methodology, C.J.W.; Validation, C.J.W.; Formal Analysis, C.J.W.; Investigation, C.J.W.; Data Curation, C.J.W.; Writing—Original Draft Preparation, C.J.W. and M.B.; Writing—Review and Editing, C.J.W. and M.B.; Visualization, C.J.W. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

All data obtained and used for the evaluation are freely accessible in the following repository: Weber, Collin (2022): Spatial data of soil related microplastic case and field studies. figshare. Dataset. https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.20059022.v1, accessed on 14 July 2022.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge the support of Jan-Eric Bastijans for the temporary support with the paper evaluation.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Syberg, K.; Nielsen, M.B.; Oturai, N.B.; Clausen, L.P.W.; Ramos, T.M.; Hansen, S.F. Circular Economy and Reduction of Micro(Nano)Plastics Contamination. J. Hazard. Mater. Adv. 2022, 5, 100044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Persson, L.; Carney Almroth, B.M.; Collins, C.D.; Cornell, S.; de Wit, C.A.; Diamond, M.L.; Fantke, P.; Hassellöv, M.; MacLeod, M.; Ryberg, M.W.; et al. Outside the Safe Operating Space of the Planetary Boundary for Novel Entities. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2022, 56, 1510–1521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrady, A.L. The Plastic in Microplastics: A Review. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2017, 119, 12–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Geyer, R.; Jambeck, J.R.; Law, K.L. Production, Use, and Fate of All Plastics Ever Made. Sci. Adv. 2017, 3, e1700782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zubris, K.A.V.; Richards, B.K. Synthetic Fibers as an Indicator of Land Application of Sludge. Environ. Pollut. 2005, 138, 201–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, B.; Yang, X.; Chen, L.; Chao, J.; Teng, J.; Wang, Q. Microplastics in Soils: A Review of Possible Sources, Analytical Methods and Ecological Impacts. J. Chem. Technol. Biotechnol. 2020, 37, 1045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weber, C.J.; Weihrauch, C.; Opp, C.; Chifflard, P. Investigating Microplastic Dynamics in Soils: Orientation for Sampling Strategies and Sample Pre–Procession. Land Degrad. Dev. 2021, 32, 270–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Büks, F.; Kaupenjohann, M. Global Concentrations of Microplastics in Soils—A Review. SOIL 2020, 6, 649–662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clarivate Analytics Document Search—Web of Science Core Collection. Available online: https://www.webofscience.com/wos/woscc/basic-search (accessed on 10 June 2022).

- Brandes, E.; Henseler, M.; Kreins, P. Identifying Hot-Spots for Microplastic Contamination in Agricultural Soils—A Spatial Modelling Approach for Germany. Environ. Res. Lett. 2021, 16, 104041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weihrauch, C. Dynamics Need Space—A Geospatial Approach to Soil Phosphorus’ Reactions and Migration. Geoderma 2019, 354, 113775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Willgoose, G. Principles of Soilscape and Landscape Evolution, 1st ed.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2018; ISBN 978-1-139-02933-9. [Google Scholar]

- Shen, M.; Huang, W.; Chen, M.; Song, B.; Zeng, G.; Zhang, Y. (Micro)Plastic Crisis: Un-Ignorable Contribution to Global Greenhouse Gas Emissions and Climate Change. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 254, 120138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oldenkamp, R.; Hoeks, S.; Čengić, M.; Barbarossa, V.; Burns, E.E.; Boxall, A.B.A.; Ragas, A.M.J. A High-Resolution Spatial Model to Predict Exposure to Pharmaceuticals in European Surface Waters: EPiE. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2018, 52, 12494–12503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fuller, S.; Gautam, A. A Procedure for Measuring Microplastics Using Pressurized Fluid Extraction. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2016, 50, 5774–5780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huerta Lwanga, E.; Mendoza Vega, J.; Ku Quej, V.; de los Angeles Chi, J.; Del Sanchez Cid, L.; Chi, C.; Escalona Segura, G.; Gertsen, H.; Salánki, T.; van der Ploeg, M.; et al. Field Evidence for Transfer of Plastic Debris along a Terrestrial Food Chain. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 14071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, M.; Lu, S.; Song, Y.; Lei, L.; Hu, J.; Lv, W.; Zhou, W.; Cao, C.; Shi, H.; Yang, X.; et al. Microplastic and Mesoplastic Pollution in Farmland Soils in Suburbs of Shanghai, China. Environ. Pollut. 2018, 242, 855–862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Piehl, S.; Leibner, A.; Löder, M.G.J.; Dris, R.; Bogner, C.; Laforsch, C. Identification and Quantification of Macro- and Microplastics on an Agricultural Farmland. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 17950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scheurer, M.; Bigalke, M. Microplastics in Swiss Floodplain Soils. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2018, 52, 3591–3598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, G.S.; Liu, Y.F. The Distribution of Microplastics in Soil Aggregate Fractions in Southwestern China. Sci. Total Environ. 2018, 642, 12–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Corradini, F.; Meza, P.; Eguiluz, R.; Casado, F.; Huerta-Lwanga, E.; Geissen, V. Evidence of Microplastic Accumulation in Agricultural Soils from Sewage Sludge Disposal. Sci. Total Environ. 2019, 671, 411–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, M.; Zhao, Y.; Qin, X.; Jia, W.; Chai, L.; Huang, M.; Huang, Y. Microplastics from Mulching Film Is a Distinct Habitat for Bacteria in Farmland Soil. Sci. Total Environ. 2019, 688, 470–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afrin, S.; Uddin, M.K.; Rahman, M.M. Microplastics Contamination in the Soil from Urban Landfill Site, Dhaka, Bangladesh. Heliyon 2020, 6, e05572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chai, B.; Wei, Q.; She, Y.; Lu, G.; Dang, Z.; Yin, H. Soil Microplastic Pollution in an E-Waste Dismantling Zone of China. Waste Manag. 2020, 118, 291–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, Y.R.; Kim, Y.-N.; Yoon, J.-H.; Dickinson, N.; Kim, K.-H. Plastic Contamination of Forest, Urban, and Agricultural Soils: A Case Study of Yeoju City in the Republic of Korea. J. Soils Sediments 2021, 21, 1962–1973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Helcoski, R.; Yonkos, L.T.; Sanchez, A.; Baldwin, A.H. Wetland Soil Microplastics Are Negatively Related to Vegetation Cover and Stem Density. Environ. Pollut. 2020, 256, 113391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.; Liu, Q.; Jia, W.; Yan, C.; Wang, J. Agricultural Plastic Mulching as a Source of Microplastics in the Terrestrial Environment. Environ. Pollut. 2020, 260, 114096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lechthaler, S.; Esser, V.; Schüttrumpf, H.; Stauch, G. Why Analysing Microplastics in Floodplains Matters: Application in a Sedimentary Context. Environ. Sci. Process. Impacts 2021, 23, 117–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Wufuer, R.; Duo, J.; Wang, S.; Luo, Y.; Zhang, D.; Pan, X. Microplastics in Agricultural Soils: Extraction and Characterization after Different Periods of Polythene Film Mulching in an Arid Region. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 749, 141420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van den Berg, P.; Huerta-Lwanga, E.; Corradini, F.; Geissen, V. Sewage Sludge Application as a Vehicle for Microplastics in Eastern Spanish Agricultural Soils. Environ. Pollut. 2020, 261, 114198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, B.; Wang, J.; Zhang, H.; Shi, H.; Fei, Y.; Huang, S.; Tong, Y.; Wen, D.; Luo, Y.; Barceló, D. Microplastics in Agricultural Soils on the Coastal Plain of Hangzhou Bay, East China: Multiple Sources Other than Plastic Mulching Film. J. Hazard. Mater. 2020, 388, 121814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boughattas, I.; Hattab, S.; Zitouni, N.; Mkhinini, M.; Missawi, O.; Bousserrhine, N.; Banni, M. Assessing the Presence of Microplastic Particles in Tunisian Agriculture Soils and Their Potential Toxicity Effects Using Eisenia Andrei as Bioindicator. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 796, 148959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, L.; Wu, D.; Liu, P.; Hu, W.; Xu, L.; Sun, Y.; Wu, Q.; Tian, K.; Huang, B.; Yoon, S.J.; et al. Occurrence, Distribution and Affecting Factors of Microplastics in Agricultural Soils along the Lower Reaches of Yangtze River, China. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 794, 148694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Corradini, F.; Casado, F.; Leiva, V.; Huerta-Lwanga, E.; Geissen, V. Microplastics Occurrence and Frequency in Soils under Different Land Uses on a Regional Scale. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 752, 141917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cyvin, J.B.; Ervik, H.; Kveberg, A.A.; Hellevik, C. Macroplastic in Soil and Peat. A Case Study from the Remote Islands of Mausund and Froan Landscape Conservation Area, Norway; Implications for Coastal Cleanups and Biodiversity. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 787, 147547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, S.; Lu, H.; Liu, Y. The Occurrence of Microplastics in Farmland and Grassland Soils in the Qinghai-Tibet Plateau: Different Land Use and Mulching Time in Facility Agriculture. Environ. Pollut. 2021, 279, 116939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, C.; Lu, B.; Guo, W.; Tang, X.; Wang, X.; Xue, Y.; Wang, L.; He, X. Distribution of Microplastics in Mulched Soil in Xinjiang, China. Int. J. Agric. Biol. Eng. 2021, 14, 196–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ragoobur, D.; Huerta-Lwanga, E.; Somaroo, G.D. Microplastics in Agricultural Soils, Wastewater Effluents and Sewage Sludge in Mauritius. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 798, 149326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sobhani, Z.; Luo, Y.; Gibson, C.T.; Tang, Y.; Naidu, R.; Megharaj, M.; Fang, C. Collecting Microplastics in Gardens: Case Study (i) of Soil. Front. Environ. Sci. 2021, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Li, J.; Liu, S.; Li, H.; Chen, X.; Peng, C.; Zhang, P.; Liu, X. Distinct Microplastic Distributions in Soils of Different Land-Use Types: A Case Study of Chinese Farmlands. Environ. Pollut. 2021, 269, 116199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, D.; Chen, Y.; Tong, Y.; Wang, H.; Zhang, H.; Luo, Y. Quantification of Microplastics in Soils Using Accelerated Solvent Extraction: Comparison with a Visual Sorting Method. Bull. Environ. Contam. Toxicol. 2021, 107, 770–777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Li, L.; Li, R.; Xu, L.; Shen, Y.; Li, S.; Tu, C.; Wu, L.; Christie, P.; Luo, Y. Microplastics in an Agricultural Soil Following Repeated Application of Three Types of Sewage Sludge: A Field Study. Environ. Pollut. 2021, 289, 117943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, L.; Zhang, J.; Liu, Y.; Chen, L.; Tao, S.; Liu, W. Distribution Characteristics of Microplastics in Agricultural Soils from the Largest Vegetable Production Base in China. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 756, 143860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tagg, A.S.; Brandes, E.; Fischer, F.; Fischer, D.; Brandt, J.; Labrenz, M. Agricultural Application of Microplastic-Rich Sewage Sludge Leads to Further Uncontrolled Contamination. Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 806, 150611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grause, G.; Kuniyasu, Y.; Chien, M.-F.; Inoue, C. Separation of Microplastic from Soil by Centrifugation and Its Application to Agricultural Soil. Chemosphere 2022, 288, 132654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, G.; Yang, L.; Xu, L.; Yang, J. Soil Microplastic Pollution under Different Land Uses in Tropics, Southwestern China. Chemosphere 2022, 289, 133176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sarkar, A.; Deb, S.; Ghosh, S.; Mandal, S.; Quazi, S.A.; Kushwaha, A.; Hoque, A.; Choudhury, A. Impact of Anthropogenic Pollution on Soil Properties in and around a Town in Eastern India. Geoderma Reg. 2022, 28, e00462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scopetani, C.; Chelazzi, D.; Cincinelli, A.; Martellini, T.; Leiniö, V.; Pellinen, J. Hazardous Contaminants in Plastics Contained in Compost and Agricultural Soil. Chemosphere 2022, 293, 133645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Müller, A.; Kocher, B.; Altmann, K.; Braun, U. Determination of Tire Wear Markers in Soil Samples and Their Distribution in a Roadside Soil. Chemosphere 2022, 294, 133653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodrigues, R.R. Downside up: Science Matters Equally to the Global South. Commun Earth Env. 2021, 2, 100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koutnik, V.S.; Leonard, J.; Alkidim, S.; DePrima, F.J.; Ravi, S.; Hoek, E.M.V.; Mohanty, S.K. Distribution of Microplastics in Soil and Freshwater Environments: Global Analysis and Framework for Transport Modeling. Environ. Pollut. 2021, 274, 116552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Möller, J.N.; Löder, M.G.J.; Laforsch, C. Finding Microplastics in Soils: A Review of Analytical Methods. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2020, 54, 2078–2090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prata, J.C.; da Costa, J.P.; Duarte, A.C.; Rocha-Santos, T. Methods for Sampling and Detection of Microplastics in Water and Sediment: A Critical Review. TrAC Trends Anal. Chem. 2019, 110, 150–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, D.; Schütze, B.; Heinze, W.M.; Steinmetz, Z. Sample Preparation Techniques for the Analysis of Microplastics in Soil—A Review. Sustainability 2020, 12, 9074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Y.; Flury, M. How to Take Representative Samples to Quantify Microplastic Particles in Soil? Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 784, 147166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tekman, M.; Gutow, L.; Macario, A.; Haas, A.; Walter, A.; Bergmann, M. LITTERBASE: Online Portal for Marine Litter. Available online: https://litterbase.awi.de/litter (accessed on 10 June 2022).

- Gabelica, M.; Bojčić, R.; Puljak, L. Many Researchers Were Not Compliant with Their Published Data Sharing Statement: Mixed-Methods Study. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 2022, 150, 33–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sajjad, M.; Huang, Q.; Khan, S.; Khan, M.A.; Liu, Y.; Wang, J.; Lian, F.; Wang, Q.; Guo, G. Microplastics in the Soil Environment: A Critical Review. Environ. Technol. Innov. 2022, 27, 102408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rehm, R.; Zeyer, T.; Schmidt, A.; Fiener, P. Soil erosion as transport pathway of microplastic from agriculture soils to aquatic ecosystems. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 795, 148774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, Z.; Xiangyuang, G.; Xu, X.; Zhao, L.; Qiu, H.; Cao, X. Microplastics in the soil-groundwater environment: Aging, migration, and co-transport of contaminants—A critical review. J. Hazard. Mater. 2021, 419, 126455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ritchie, H.; Roser, M. Land Use. Our World Data 2013. Available online: https://ourworldindata.org/land-use (accessed on 5 March 2022).

- Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO). Other Global Soil Maps and Databases|FAO SOILS PORTAL|Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. Available online: https://www.fao.org/soils-portal/data-hub/soil-maps-and-databases/other-global-soil-maps-and-databases/en/ (accessed on 10 June 2022).

- Rillig, M.C.; Ziersch, L.; Hempel, S. Microplastic Transport in Soil by Earthworms. Sci Rep 2017, 7, 1362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kale, S.K.; Deshmuk, A.G.; Dudhare, M.S.; Patil, V.B. Microbial Degradation Of Plastic—A Review. IJPR 2020, 13, 952–961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zumstein, M.T.; Schintlmeister, A.; Nelson, T.F.; Baumgartner, R.; Woebken, D.; Wagner, M.; Kohler, H.-P.E.; McNeill, K.; Sander, M. Biodegradation of Synthetic Polymers in Soils: Tracking Carbon into CO 2 and Microbial Biomass. Sci. Adv. 2018, 4, eaas9024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Souza Machado, A.A.; Lau, C.W.; Till, J.; Kloas, W.; Lehmann, A.; Becker, R.; Rillig, M.C. Impacts of Microplastics on the Soil Biophysical Environment. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2018, 52, 9656–9665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Souza Machado, A.A.; Lau, C.W.; Kloas, W.; Bergmann, J.; Bachelier, J.B.; Faltin, E.; Becker, R.; Görlich, A.S.; Rillig, M.C. Microplastics Can Change Soil Properties and Affect Plant Performance. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2019, 53, 6044–6052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Metz, T.; Koch, M.; Lenz, P. Extracting Microplastic Decay Rates from Field Data. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 1223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Metz, T.; Koch, M.; Lenz, P. Quantification of Microplastics: Which Parameters Are Essential for a Reliable Inter-Study Comparison? Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2020, 157, 111330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).