1. Introduction

As the first 4th-generation synchrotron light source in Asia and the first high-energy source in China, HEPS is a greenfield facility with a storage ring energy of 6 GeV and a circumference of 1360 m [

1]. It provides critical support for technological and industrial innovation breakthroughs, serving as a state-of-the-art multi-disciplinary experimental platform for basic science research. The 15 beamlines in Phase I are currently under construction and commissioning, with acceptance inspection expected by the end of 2025, after which they will be open to public services [

2].

According to estimated data rates, the 15 beamlines generate an average of 800 TB of raw experimental data per day, with a maximum peak data generation rate of 3.2 Tb/s. This data volume will further increase with the completion of over 90 beamlines in Phase II. All data must be transferred from beamlines to the HEPS data center, demanding a high-performance network with high bandwidth, ultra-low latency, and zero packet loss to meet both the high-throughput computing (HTC) and high-performance computing (HPC) needs from beamline scientists.

With the evolution of Ethernet-enabled technologies such as RoCE and advanced congestion control, Infiniband and proprietary networks have ceased to dominate TOP500 supercomputers and open science platforms since 2020. Meanwhile, market shares for Mellanox, as well as storage, hyperscale, and hyperconverged market shares have shifted heavily towards Ethernet use, and this trend is projected to continue [

3]. According to the statistics of the TOP500 in November 2022, Ethernet is in first place when comparing interconnect family systems, with a proportion of 46.6%. Nearly all supercomputer architectures as well as leading data center providers utilize RDMA in production today [

4]. Based on the former research and evaluation of RoCE in the IHEP data center [

5], this paper designs a high-performance, scalable RoCE-based network architecture to address HEPS’ scientific data storage, computing, and analysis needs.

2. Network Architecture Design

2.1. A Spine–Leaf Architecture

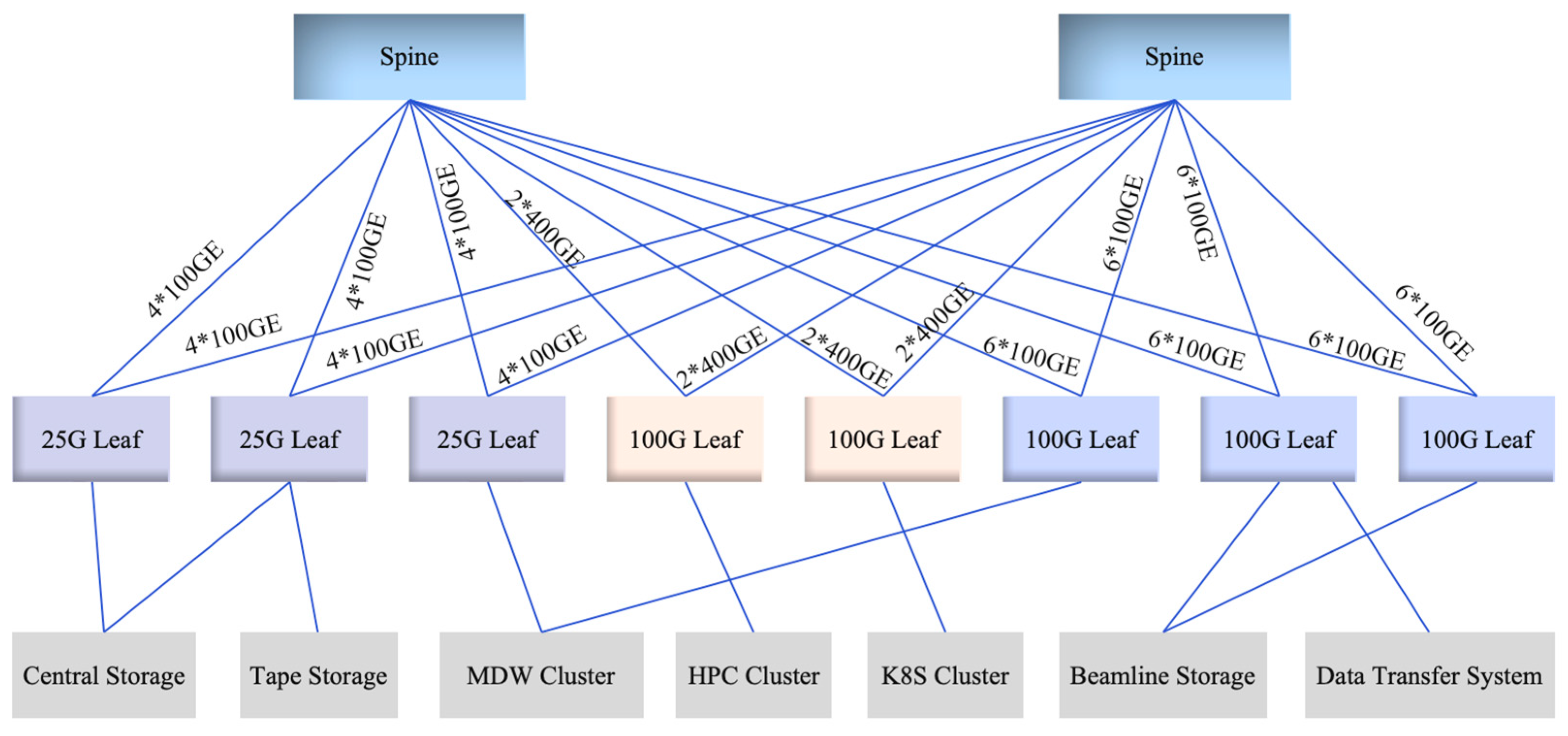

We designed a spine–leaf architecture consisting of two spine switches and eight leaf switches, with 25G and 100G Ethernet connections deployed to accommodate diverse bandwidth requirements [

6], as illustrated in

Figure 1. The access-layer gateway functions are deployed on leaf nodes, which reduces latency and optimizes traffic routing between compute/storage resources and the core network. Between the spine and leaf layers, dynamic routing protocols enable adaptive path establishment, while Equal-Cost Multipath (ECMP) distributes traffic across redundant links, ensuring load balancing, maximizing throughput, and enhancing fault tolerance. This architecture enables scalability for data-intensive applications including AI training, HPC, and real-time analytics.

Data Center Quantized Congestion Notification (DCQCN), a pivotal congestion control framework standardized in IEEE 802.1Qau, is tailored explicitly for lossless, low-latency RDMA traffic, marking a key distinction from traditional TCP-based mechanisms. This framework resolves core challenges in modern data centers, such as buffer overflow and in-cast congestion. A hallmark innovation of DCQCN is its compatibility with Priority-based Flow Control (PFC), which alleviates buffer starvation across heterogeneous traffic classes [

7]. By integrating with PFC, DCQCN balances congestion control and traffic prioritization, enabling efficient coexistence between latency-sensitive RDMA flows and best-effort TCP traffic [

8]. Moreover, its adaptive rate adjustment mechanism accommodates the bursty workloads characteristic of AI training, HPC, and cloud-scale analytics, where instantaneous bandwidth demands exhibit significant fluctuations. For these reasons, DCQCN has been deployed in the HEPS data center to minimize end-to-end latency and optimize bandwidth utilization efficiency.

2.2. Scalability Analysis

A key design feature of the RoCE-based spine–leaf architecture for the HEPS data center is that there are no direct interconnections between spine nodes in the current deployment. This spine-disjoint topology simplifies the core layer structure while laying a flexible foundation for bandwidth expansion. The initial architecture deploys two spine switches to interconnect with eight leaf switches, which is sufficient to support the data transmission demands of 15 beamlines in HEPS Phase I.

When the network bandwidth demand surges (e.g., with the expansion to over 90 beamlines in HEPS Phase II), the architecture enables scalable expansion by simply increasing the number of spine nodes and leaf nodes. Newly added spine switches only need to establish physical and logical connections with the leaf switches, and no modifications to the configuration of the original spine–leaf links or leaf node access policies are required. The ECMP protocol deployed in the architecture automatically identifies the newly added spine–leaf paths and redistributes traffic across all available equal-cost paths, realizing multipath load balancing. This expansion mode ensures that the network throughput increases linearly with the number of spine nodes, effectively eliminating bandwidth bottlenecks in the core layer and maintaining the non-blocking forwarding characteristics of the flat spine–leaf topology for HEPS’ growing data transmission needs.

2.3. Fault-Tolerance Analysis

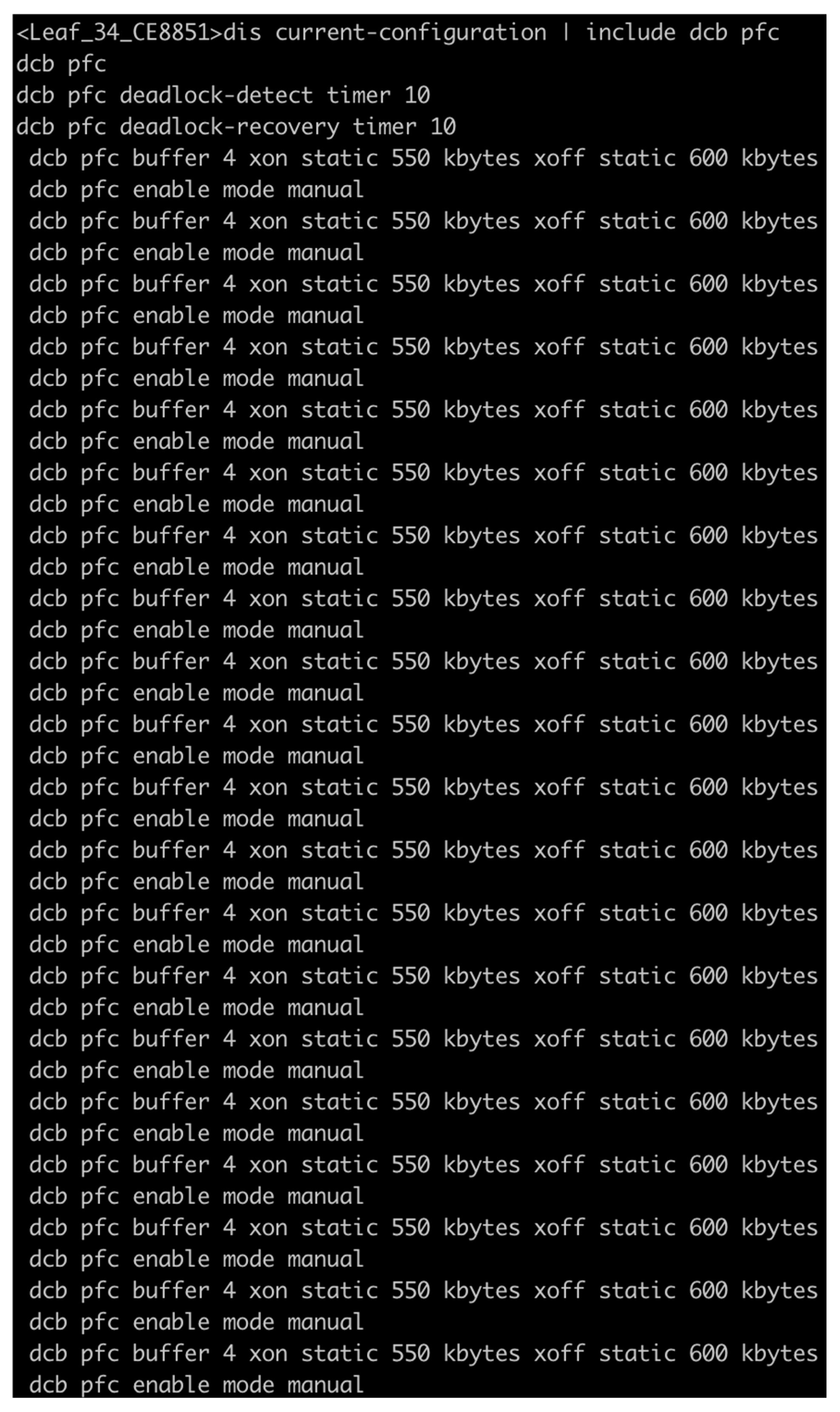

The fault-tolerance capability of the RoCE-based spine–leaf architecture for the HEPS data center is designed to address extreme conditions such as node failures, link interruptions, and network congestion. The dual-spine and eight-leaf redundant topology, combined with the ECMP protocol, enables automatic traffic redistribution across alternative paths when a spine–leaf link fails, eliminating single points of failure. The globally enabled PFC is configured with a 10 s deadlock detection and recovery timer, which proactively mitigates queue stagnation in extreme congestion scenarios and prevents packet loss caused by buffer overflow (the configuration can be seen in

Section 3.1). Additionally, the DCQCN framework’s adaptive rate adjustment mechanism dynamically responds to bursty traffic peaks of HEPS beamlines, avoiding congestion collapse.

2.4. Security Analysis of RDMA Traffic

RDMA traffic in the HEPS data center faces security risks such as unauthorized memory access and data eavesdropping due to its direct memory access characteristic and lack of native encryption. To address these issues, we propose a lightweight security framework tailored to RDMA’s low-latency requirements for HEPS. The framework implements mutual authentication between endpoints based on the Transport Layer Security (TLS) protocol, restricting unauthorized nodes from accessing the RDMA network. For sensitive scientific data transmitted by beamlines, selective encryption is adopted for memory regions involved in RDMA operations, using the AES-128-GCM algorithm to ensure data confidentiality without compromising transmission performance. Moreover, we isolate RDMA traffic in PFC queue 4 and implement role-based access control (RBAC) for beamline servers, preventing malicious traffic injections. The detailed configurations are also shown in the experimental environment below.

3. Results

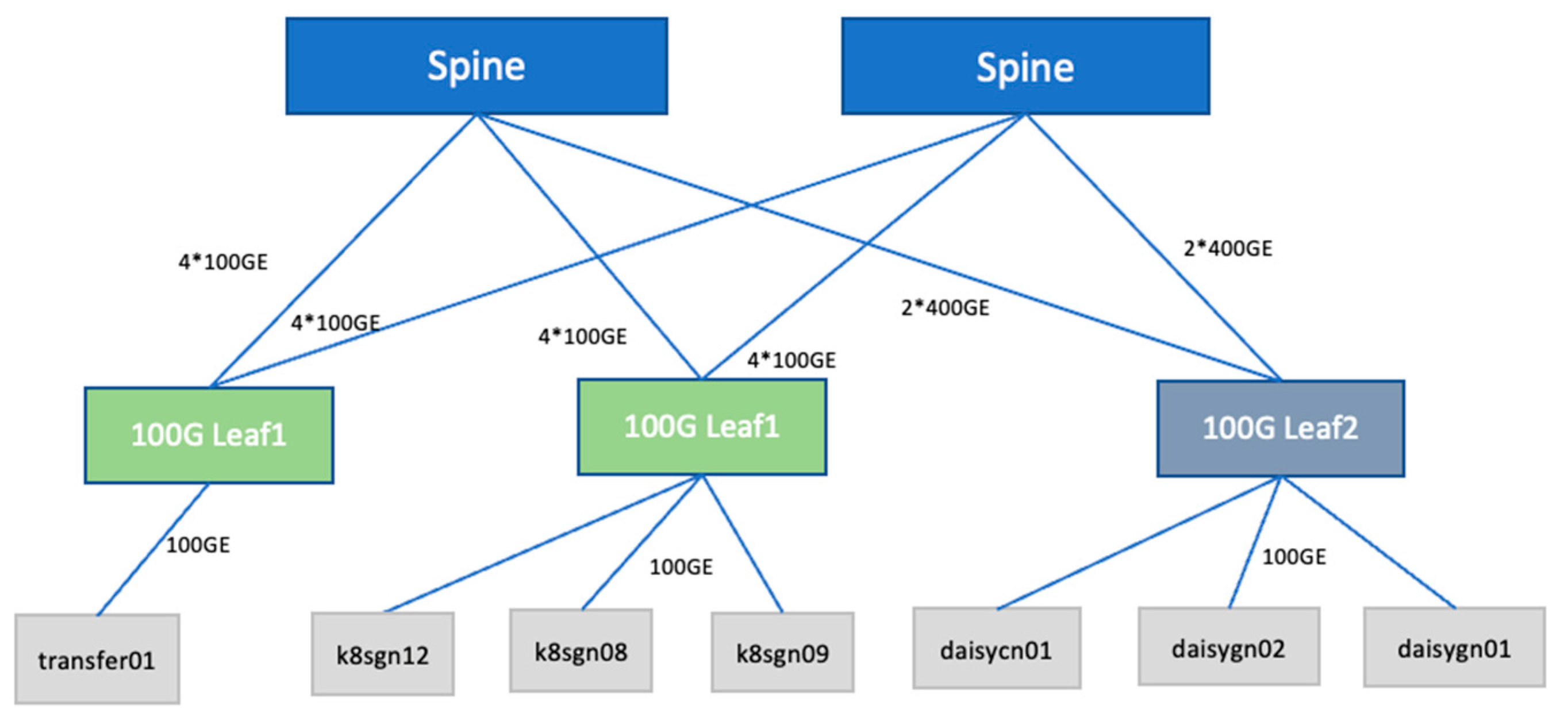

We selected 7 servers currently in operation at the HEPS data center to conduct network throughput tests. The 7 servers include a data transfer server (transfer01), Kubernetes nodes (k8sgn08/k8sgn09/k8sgn12), and software framework nodes (daisycn01/daisygn02/daisygn01).

3.1. Experimental Environment

The network topology is shown in

Figure 2. Each server is uplinked to a 100G leaf switch, which then uplinks to the two spine switches.

The specifications of the test environment, including network interface card models, operating systems, network driver versions of the testing servers, as well as the manufacturers and models of network switches, are presented in

Table 1.

We use the default ECMP hash algorithm. The PFC function is globally enabled (seen in

Figure 3), complemented by a 10 s deadlock detection timer and a 10 s deadlock recovery timer to proactively mitigate potential queue stagnation. Across multiple physical interfaces, a consistent manual PFC mode is configured, with exclusive activation in queue 4, designated for loss-sensitive traffic. The queue’s buffer thresholds are statically set, with the xon threshold (triggering transmission resumption) set at 550 kbytes and the xoff threshold (initiating pause frame sending) set at 600 kbytes. This setup ensures that when the queue’s buffer utilization hits 600 kbytes, the switch sends PFC pause frames to the upstream device to prevent packet loss. Meanwhile, transmission resumes automatically once the buffer usage drops to 550 kbytes.

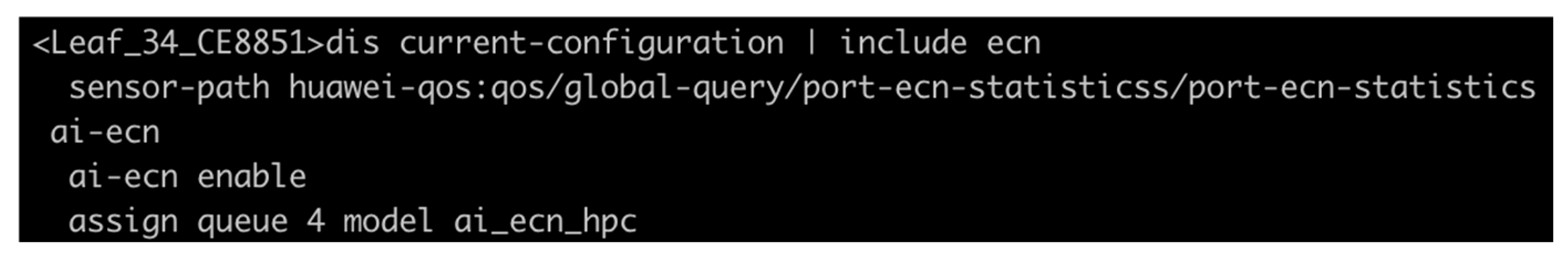

DCQCN is globally enabled (seen in

Figure 4), with queue 4 assigned to the “ai_ecn_hpc” model and optimized for high-performance computing scenarios. This setup intelligently adjusts ECN marking based on real-time traffic, complementing PFC to ensure lossless, low-latency transmission for data-intensive workloads like scientific research data transfer.

3.2. Performance Testing with PerfTest

PerfTest is an open-source performance testing toolkit specifically designed to evaluate the performance of InfiniBand and RoCE networks. It focuses on low-level hardware and protocol metrics, making it indispensable for validating, benchmarking, and optimizing high-speed interconnects in data centers [

9].

PerfTest includes a suite of specialized tools tailored to different InfiniBand/RDMA operations, with some common examples as follows:

ib_write_bw/ib_write_lat: Test bandwidth and latency for RDMA Write operations.

ib_read_bw/ib_read_lat: Focus on RDMA Read operations.

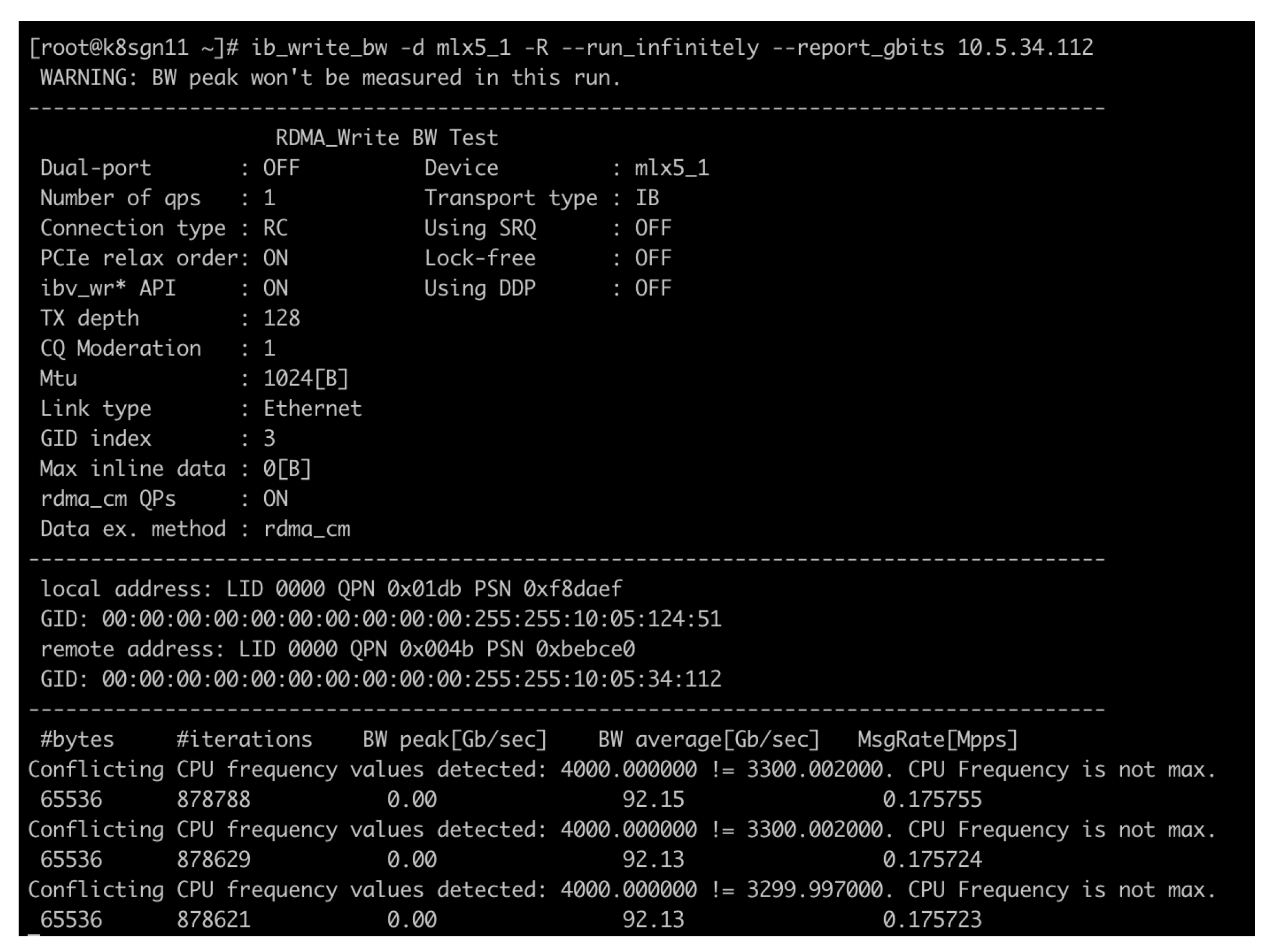

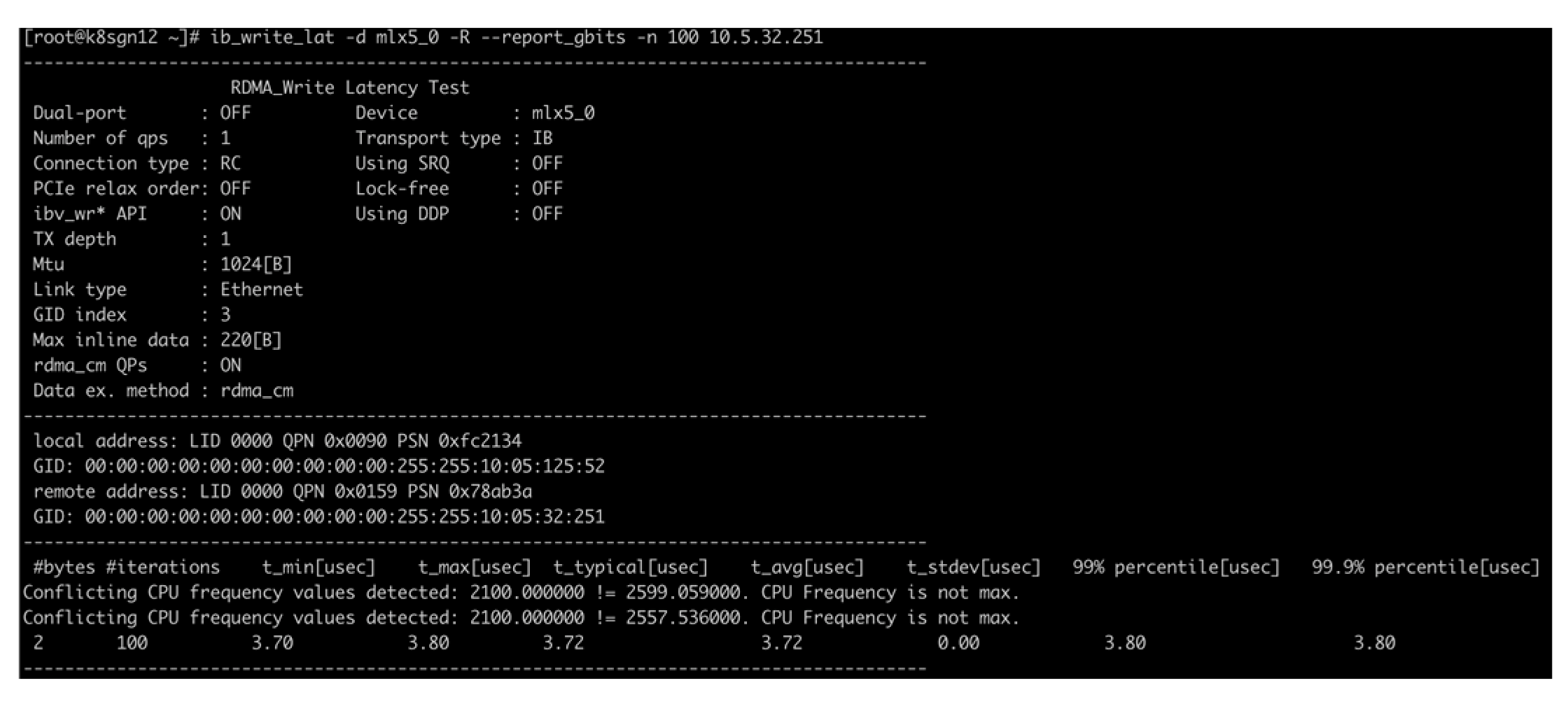

Given that the construction goal of HEPS Phase I prioritizes the timely transfer of beamline-generated to the data center, we emphasized RDMA write bandwidth and latency, which are the metrics critical for meeting the project’s real-time data transfer requirements. For testing, we selected two servers connected to different leaf nodes and conducted ib_write_bw and ib_write_lat tests. The results are shown in

Figure 5 and

Figure 6.

Figure 5 demonstrates that the average network bandwidth of RDMA Write operations between two 100G servers across spine switches reaches 92 Gb/s.

Figure 6 shows that the average network latency of RDMA Write operations between these servers is approximately 3.72 μs. These results indicate that cross-spine communication between servers achieves near-theoretical peak throughput with ultra-low latency, as expected.

3.3. Comparative Analysis of Congestion Control

To validate the superiority of DCQCN used in this paper, we compared it with two mainstream RDMA congestion control algorithms: DCTCP (Data Center TCP) [

10] and HPCC (High Precision Congestion Control) [

11]. All tests were conducted based on the network topology in

Figure 2 and the hardware configuration in

Table 1, with gateways configured on all leaf switches as well.

Each test was repeated 10,000 times to ensure statistical stability, with results summarized in

Table 2. DCQCN achieves an average bandwidth of 92.1 Gb/s, approaching the theoretical peak of 100 G Ethernet (≈94 Gb/s, accounting for frame header and protocol overheads). This outperforms HPCC by 4.1% (88.5 Gb/s) and DCTCP by 11.9% (82.3 Gb/s). Its PFC-based lossless queue management avoids packet loss-induced retransmissions, acting as a bottleneck for DCTCP (coarse-grained congestion window adjustment) and HPCC (occasional throughput trade-offs for latency).

DCQCN also delivers the lowest average latency (3.72 μs), outperforming HPCC by 30.4% (4.85 μs) and DCTCP by 66.9% (6.21 μs). Its integration with PFC eliminates buffer overflow delays (a key issue for DCTCP), while the “ai_ecn_hpc” model’s fine-grained rate adjustment outperforms HPCC’s delay-based feedback, which is critical for avoiding latency outliers that disrupt HEPS’ real-time beamline data analysis.

These results confirm DCQCN-PFC’s superiority in balancing high bandwidth and ultra-low latency, making it the optimal congestion control choice for HEPS’ RoCE-based data transfer.

4. Discussion

The core working hypothesis of this study is that an RoCE-based spine–leaf network architecture, combined with Data Center Quantized Congestion Notification (DCQCN) and Priority-based Flow Control (PFC), can meet the high bandwidth, ultra-low-latency, and scalable requirements of HEPS scientific data transmission (covering data offloading from beamlines, computing–node interaction, and storage access). The experimental results from the seven in-service HEPS servers (including transfer, Kubernetes, and software framework nodes) strongly validate this hypothesis.

In the PerfTest evaluations, the average bandwidth of RDMA Write operations (via ib_write_bw) between 100G servers across spine switches reached 92 Gb/s, which is close to the theoretical peak bandwidth of 100 G Ethernet (≈94 Gb/s, after accounting for protocol overheads such as frame headers). This performance confirms that the dual-spine (HUAWEI CE9860 (Shenzhen, China)) and multi-leaf (HUAWEI CE8850/CE8851) topology, paired with Equal-Cost Multipath (ECMP) for traffic distribution, effectively eliminates inter-layer bandwidth bottlenecks. ECMP’s ability to spread traffic across redundant links not only maximizes throughput but also ensures load balancing, which is critical for handling HEPS’ bursty data generation.

Meanwhile, the average latency of RDMA Write operations (via ib_write_lat) was approximately 3.72 µs, which is far lower than the latency of traditional TCP/IP networks (typically 50–100 µs for 100G links) and comparable to dedicated InfiniBand networks (≈4–5 µs for similar-scale deployments). This ultra-low latency stems from two key design decisions: (1) Locating access-layer gateway functions at leaf nodes, which reduces routing hops between compute/storage resources and the core network (avoiding additional latency from intermediate gateways), and (2) integrating DCQCN with PFC, which addresses buffer overflow and in-cast congestion, which are two major causes of latency spikes in RDMA networks. Notably, the consistency of results across multiple test iterations (e.g., stable 92 Gb/s bandwidth and 3.72 µs latency) further proves the architecture’s ability to maintain reliability under the variable workloads of HEPS (e.g., alternating between real-time data analysis and offline tape storage).

Author Contributions

Overall coordination and manuscript writing, S.Z.; Literature search, T.C.; Data collection, Y.W.; Figure preparation, M.Q.; Final review of the manuscript, F.Q. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 12175258).

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- He, P.; Cao, J.; Lin, G.; Li, M.; Dong, Y.; Pan, W.; Tao, Y. Update on HEPS Progress. Synchrotron Radiat. News 2023, 36, 16–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Zhang, Y.; Liu, Y.; Li, P.; Hu, H.; Wang, L.; He, P.; Dong, Y.; Zhang, C. A high-throughput big-data orchestration and processing system for the High Energy Photon Source. Synchrotron Radiat. 2023, 30, 1086–1091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kalia, A.; Kaminsky, M.; Andersen, D.G. Design guidelines for high performance {RDMA} systems. In Proceedings of the 2016 USENIX Annual Technical Conference (USENIX ATC 16), Denver, CO, USA, 22–24 June 2016; pp. 437–450. [Google Scholar]

- Li, W.; Zhang, J.; Liu, Y.; Zeng, G.; Wang, Z.; Zeng, C.; Zhou, P.; Wang, Q.; Chen, K. Cepheus: Accelerating datacenter applications with high-performance roce-capable multicast. In Proceedings of the 2024 IEEE International Symposium on High-Performance Computer Architecture (HPCA), Edinburgh, UK, 2–6 March 2024; IEEE: Edinburgh, UK; pp. 908–921. [Google Scholar]

- Zeng, S.; Qi, F.; Han, L.; Gong, X.; Wu, T. Research and Evaluation of RoCE in IHEP Data Center. In EPJ Web of Conferences; EDP Sciences: Bloomsbury, UK, 2021; Volume 251, p. 02018. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Y.; Geng, Y.D.; Bi, X.X.; Li, X.; Tao, Y.; Cao, J.S.; Dong, Y.H.; Zhang, Y. Mamba: A systematic software solution for beamline experiments at HEPS. Synchrotron Radiat. 2022, 29, 664–669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, Y.; Shi, Z.; Nie, Y.; Qian, L. Dcqcn advanced (dcqcn-a): Combining ecn and rtt for rdma congestion control. In Proceedings of the 2021 IEEE 5th Information Technology, Networking, Electronic and Automation Control Conference (ITNEC), Xi’an, China, 15–17 October 2021; IEEE: Xi’an, China; Volume 5, pp. 1192–1198. [Google Scholar]

- Gao, Y.; Yang, Y.; Chen, T.; Zheng, J.; Mao, B.; Chen, G. DCQCN+: Taming Large-Scale Incast Congestion in RDMA over Ethernet Networks. In Proceedings of the 2018 IEEE 26th International Conference on Network Protocols (ICNP), Cambridge, UK, 25–27 September 2018; pp. 110–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OFED Perftest. 2024. Available online: https://github.com/linux-rdma/ (accessed on 10 August 2025).

- Kuhlewind, M.; Wagner, D.P.; Espinosa, J.M.R.; Briscoe, B. Using data center TCP (DCTCP) in the Internet. In Proceedings of the 2014 IEEE Globecom Workshops (GC Wkshps), Austin, TX, USA, 8–12 December 2014; pp. 583–588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Miao, R.; Liu, H.H.; Zhuang, Y.; Feng, F.; Tang, L.; Cao, Z.; Zhang, M.; Kelly, F.; Alizadeh, M.; et al. HPCC: High precision congestion control. In Proceedings of the SIGCOMM ‘19: Proceedings of the ACM Special Interest Group on Data Communication, Beijing, China, 19–23 August 2019; pp. 44–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).