Abstract

Quality of experience (QoE) metrics can be used to assess user perception and satisfaction in data services applications delivered over the Internet. End-to-end metrics are formed because QoE is dependent on both the users’ perception and the service used. Traditionally, network optimization has focused on improving network properties such as the quality of service (QoS). In this paper we examine adaptive streaming over a software-defined network environment. We aimed to evaluate and study the media streams, aspects affecting the stream, and the network. This was undertaken to eventually reach a stage of analysing the network’s features and their direct relationship with the perceived QoE. We then use machine learning to build a prediction model based on subjective user experiments. This will help to eliminate future physical experiments and automate the process of predicting QoE.

1. Introduction

MPEG dynamic adaptive streaming over HTTP (DASH) is an adaptive bit-rate streaming methodology which has many abilities providing the best quality streaming of multimedia-related applications across the Internet, a leap from traditional HTTP web servers. It works based on the criteria of breaking down video content into small sequential data segments, which further work over HTTP. Every segment has a small time duration of playback that consists of multiple characteristics, such as a short movie clip or the time broadcast of an event-like show or sports program. The MPEG-DASH can adapt to alternating network fluctuations and enable the best quality playback with a minimal number of re-buffering occasions. One of the main problems that we are trying to solve with our research is determining the correct classification methods for noisy data such as the output of a DASH media stream.

There is a considerable rise in the general quality of experience (QoE) anticipated by users across multimedia distribution strategies such as live streaming of video. Since the number of online client implementations and the equipment usage have increased, there is a significant change in the capability of the end equipment and facilities, such as network bandwidth, which are usually distributed among various such as equipment. Traditionally, best-effort network construction assigns assets depending upon the request of a client and an advanced-level service level agreement (SLA) without taking application and user level necessities into consideration. The such as s are usually unsatisfied due to the perceivable unfairness. The concept of fairness within a network or between network resources can be interrupted in many ways; thus fairness can also be achieved in many different ways depending on the scenario [1]. Some of the gaps that we aimed to fill in this research include (but are not limited to): the possibility to create a hybrid environment of software-defined networks compatible with multiple network controllers and DASH media-streaming experimentation; and the creation of an experimentation framework that can enhance the multimedia quality of experience evaluation and prediction for future human-less trials and comparing its outputs, strengths and weakness with the state-of-the-art solution to provide the most advanced noise-free generated data for machine learning predictors.

In this paper, a new quality analysis method is used as a distant broadcast technique for measuring the appropriateness of the environment for contributing to multimedia video evaluation. In a laboratory experiment, contributors (past researchers) achieved this quality analysis with various listening devices in various listening surroundings involving a silent room allowing an imitation of a circumstantial noise situation. Their results show important observations of the situation and the attending device on the quality inception, and their physical settings had a direct relation to user perception. Thus, the arrangement of our video trials will be free of sound and will only target one aspect, the quality of the video perceived, in a virtual environment guided by ITU recommendations. We aim to tackle the issues of subjective evaluation of objective QoE models. We proposed an experimentation framework structure through programmable network management for the generation of machine learning (ML) training-ready data and MOS/QoE prediction. We used our test bed’s data-generated analysis with real user experimentation and ML for training and predicting QoE based on the generated monitoring data. This way with the generated prediction, limited user testing is needed in the future; hence, future researchers will simply run the generated monitored data from the network tracing tools into the prediction model, and it will generate a predicted MOS for faster and more efficient network level tests and experiments. This model is unique because we tested its data with state-of-the-art ML algorithms and achieved highly accurate prediction results. The main contributions and findings of this work outline,

- A hybrid simulation environment to run both P4 [2] and Openflow [3], along with Python 2 and 3 instances, DASH and Mininet. With all essential packages installed, an error-free test environment for running this experiment, and applying previous and similar work to compare and contrast results. Our open-source test bed configuration is shown here [4]

- A P4 SDN test bed over Mininet with the ability to control DASH initial buffering, stalling, switching, monitoring, bit rate adaptation, and bandwidth limitation over selected ports. The test bed provides the capacity for comprehensive user experiments and data collections, which lead to our insights and analysis of congestion for congestion-related experiments along with full re-configurablity over the data plane and everything mentioned above. Our open-source test bed setup is shown here [4]

- A proposed experimentation framework structure through programmable network management for the generation of ML training-ready data and MOS/QoE prediction.

- Human experiment with QoE MOS-based feedback to benchmark the accuracy of the predicted QoE and network features.

- Analysis of state-of-the-art machine learning algorithms, along with the creation of an experimentation framework for feature evaluation in network experiments. Our open-source analyses are shown here [4]

2. Problem Space and Related Work

HTTP adaptive streaming (HAS), such as MPEG-DASH, splits a broadcast file into many segments. Every segment is encrypted into the number of bit rates to attain access for the user with changing stream specifications. The video segments are consecutively requested by the client, having a maximum bit rate possible, which is approximated based on the network and user needs. The process of adaptive bit rate algorithms (ABR) is the method through which a client suggests the ideal bit rate of the part to download. ABR contains default conditions, but many of them do not reflect the difference between the multiple scenarios that may occur in a production environment and often work poorly when the organization makes changes in the work environment. A recent attempt is to link the increase in the ABR to the capabilities of the interpolation method [5], which is mainly based on a machine learning model. The ML-based ABR strategy is divided into two parts. In the first part, you can adjust the current ABR parameters. A calculation plan based on the ABR variables is proposed. Support systems allow the ABR to change variables depending on the order in which the network conditions are changed. In deep learning, this ABR variable is based on an adaptation policy, where changes are presented as the context of the flow. In deep learning, depending on the strategy used, the parameters of the ABRs, would directly affect the streaming content.

Previous research states that bit rate depends upon the ABR models having trained a predictive collection of decisions (SMASH [6]), where a ’combine grouping’ scheme was used to make a map of the network-related properties of bit rate. A supervised ML-based ABR was implemented with features related only to the bit rate status. Therefore, there are some restrictions with those predictions as features are focused on limited network factors. Both the conception of engineering and the ML algorithm selections will not be executed in a methodical fashion; moreover, the trained model has planned to support, rather than replace, the existing fixed rules that depend upon modifying the algorithm. Moreover, a recently introduced model-free strategy is Pensieve [7], which uses a reinforcement learning strategy to introduce a neural network based upon the ABR. This strategy makes no explicit assumption related to effective data. Multiple papers have reported issues such as Pensieve; therefore, it is being accompanied by implementing detailed experimental evaluation of Pensieve, keeping various sets of video content and network under observation [8]. In [9] within the training process, the results change significantly when using a web account; the deficit has a high value and does not tend to coincide. They have a high bit rate presented in their video setup. For example, when running UHD and 4K data packets, authors choose reasonably bright screens based on past learning success, indicating that the data are fragmented. A bit rate equal to the brightness percentage is reduced by 50%, the experimental model only learns to achieve maximum results, and the bit rate leads to an inaccessible video level. The heterogeneity of wireless networks means that larger variants continue to be known, and as the value of video resolution continues to grow, so does the popularity of data. This work was therefore encouraged. For research and experimentation, researchers spend an enormous amount of time in the creation of their test environment; most of these environments are quite specific to the target of their research. There are many downloadable virtual environments, such as P4 or SDN-based virtual test beds; however, these environments are very specific to their purpose. Configuring a suitable test bed that has the ability to run multiple solutions from multiple different test beds is very time consuming. Thus, we created a virtual-box environment with all the necessary libraries and applications needed to run P4, Openflow, Python 2 and 3 instances, DASH and Mininet. This provides ease for researchers to use our virtual machine setup to dive straight into testing and data generation without wasting their time and effort building the virtual setup.

Table 1 shows a list of previous HTTP adaptive video streaming databases that are widely used in research within QoE. Our generated database of encoded videos contains 6 source segment division videos and 120 different resolution videos. Our database comes with a pre-configured P4 software defined network with a server and multiple clients for testing and evaluating QoE with DASH reference player. Its main contribution is that it monitors the network and all its ports for recording DASHIF reference server packets and evaluating client data. It then generates training-ready clean data for ML usage purposes. This was performed to ease the experimentation with big data and data mining for use in ML and the understanding of multimedia network environment.

Table 1.

Comparison of publicly available QoE dataset for HTTP-based adaptive video streaming.

Furthermore, QoE is widely discussed and predicted in multiple aspects within the use of different features and multiple joint classifiers [17,18,19,20,21]. Our approach is unique in its data generation. We depend on our test bed to generate the network data required, and based on that network data, we use machine learning algorithms to predict the generation of MOS and all other features.In addition, we analyse the most effective feature from the network data that directly affects the MOS and prioritize it in our test bed. Thus, the data generated from the test bed is always training-ready to test on more algorithms.

3. Preliminaries and Methodology

The approach presented in this paper makes use of different configurations of a neural network and classification arranged to provide the best fit feature classifier and MOS prediction suitable for most of the tasks characterizing modern media streaming which is the specific goal of this work. Moreover, we focused on the design and implementation of our P4 test bed to host the DASH reference player and the ability to monitor it, where a researcher can easily extract the data and use the ML techniques we show in this paper to test and improve upon this work.

3.1. Adaptive Streaming

A multimedia data file is segregated into multiple parts or segments and then conveyed to the user using HTTP. A media presentation description (MPD) explains the particulars of the segment, which include aspects such as time, website and multimedia properties such as video resolution and bit rates. These segments can be arranged in a number of ways such as segment-based, segment time line, segment template and segment list, depending on the use case. A segment can be a media file of any type or format, such as the “ISO base media file format” and MPEG-2 transport stream; there are the two major kinds of container format. DASH can be considered as a video/audio codec sceptic. Media files are usually provided as a multiple number of illustrations, and the concerned choice of data is mainly related to the network status, equipment potential and client preferences that are responsible for allowing the adaptive bit rate streaming and impartiality of the quality of the experience.

The adaptive bit rate streaming logic is not defined by an MPEG DASH standard. Therefore, DASH can be implemented on any type of protocol. PCC expressively decreases the storage quantity at the cost of multifaceted pre-processing and execution at the client. “HTTP adaptive streaming” (HAS) deals with dynamic setup circumstances while endeavouring transport at maximum quality possible in the given circumstances.

3.2. DASH Objective Metrics

The basic remodelling of the automation is the media streaming that includes best quality on demand data and live media content. In the present scenarios, the main interest is to attain the pre-eminent quality of service and experience because of the ever aggregating network consumption and user demand. The traditional type of streaming methodologies confront multiple trials in distributing multimedia content to the end user without lowering the quality of the service. The adaptive HTTP streaming is the ever increasing content-providing tactic which delivers real-time content without negotiating quality and guarantees excellent quality of experience. The selection of bit rate must be effective and durable; it depends upon the nature of the network, and thus we argue that it must always be dynamic. The client potential points towards gaining outstanding quality of service for the end user and achieving an increase in the range of standards and procedures introduced in the adaptive HTTP streaming field. Researching and contrasting is compulsory for executing numerous techniques depending upon predefined merits. The HTTP live streaming, Microsoft smooth streaming and MPEG DASH are rising model techniques of adaptive HTTP streaming. In order to calculate the transporting execution, the experiment moves forward using G-streamer adaptive HTTP streaming. We base our calculations for transporting execution upon changing multiple networks and situations for on-demand streaming and live streaming content. The adaptive HTTP streaming method’s result is calculated and examined using pre-explained performance indices. The processed data show that each entertained method of delivery and best conductance is achieved through the predefined advantages. In short, DASH provides appreciable balanced performance throughout multiple network arrangements compared to other streaming approaches.

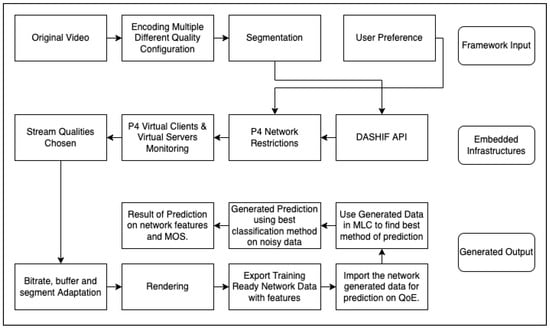

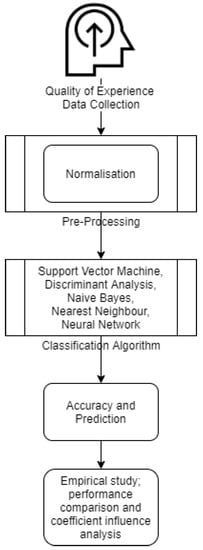

Figure 1 shows the proposed experimental framework for feature evaluation within the test bed. Features, such as network properties and factors that directly affect user QoE, are essential inputs to understanding the user’s experience. In this paper, the experiment is staged based on the encoding information in Table 2. The user will watch a video based on the video segmentation and resolution properties mentioned in Table 2; all videos are fixed on 30 frames per seconds on all video streaming qualities, with a minimum buffer time of 2 s of loaded content. The user will watch five 40 s trials of video content on a limited bandwidth of 0.5 mbps, 1 mbps, 3 mbps, 5 mbps and unlimited settings. With every trial, the user will input a video MOS (vMOS) rating based on their video experience of initial load delay, resolution change, and overall quality of experience.

Figure 1.

Proposed experimental framework for feature evaluation.

Table 2.

Video database encoding information.

3.3. Subjective Evaluation of DASH

In principle, the aim is to evaluate the relevant QoE parameters and variables that take into account the kinetic properties of the video. Common objective indicators of a subject’s performance to regularly determine their relevance to human perception are essential for evaluation. There is no subjective evaluation of DASH adaptive streaming for justifying longer video patterns, which are enough to explain the bit rate switching for the dataset that acquires the longer segment videos for various network condition sequences. Estimating the end user’s real-time quality of experience (QOE) online by exploring the apparent influence of delay, diverse packet loss rates, unstable bandwidth, and the apparent quality of using the altered size of a DASH video stream segment over a video streaming assembly under multiple video arrangements is quite possible with this paper’s approach. The performance and potential of the system and prospects depend upon the mean opinion score. The subjective evaluation of DASH gives an overview of impairments with various networks and video segments on different systems. For the test setup and procedure, we used the most recent ITU-T recommendation as general guidelines. A screen with 4K resolution was used to passively stream the content and record its segmentation, which was used to compile a separate video and present to the user to eliminate virtual environment computational power limitations from affecting the video and its MOS rating. We recommended sitting at a distance of approximately four times the height of the screen. The applied test protocol was as follows: Firstly we started with the welcome text-based information, briefing and informed consent. Then we moved on to the explanation and recommendations of the setup as recommended by the ITU-T, screening and demographic information. Following that, we showed our content, 5 video samples based on different networking runs. Our evaluation stage was next, which was a collection of 3 QoE-related questionnaires for each video sample. We ended with a debriefing which entitled the feedback and remarks from the end user. This way, we have the MOSes from the users and the recorded network data of their experiment to use for our prediction mechanisms later. Equation (1) defines MOS where R represents the user’s ratings for the given question and the question’s representation of the video’s stimulus, where R is the individual ratings for a given stimulus by N subjects. The MOS ratings were defined into 5 different classes before uploading the rating data to the training process as shown in Table 3.

where R is the individual ratings for a given stimulus by N subjects.

Table 3.

Mean opinion score scale.

4. User Experimentation

In our previous paper [22], we discussed the creation of the user experiment. In this paper, we provide a detailed perspective of the experimentation that was created. After careful consideration of the time, place and settings, we followed the ITU guide for experimentation; thus based on that guide, this section explains the user experimentation process and test bed used. ITU-T P.913 Titled: “Methods for the subjective assessment of video quality, audio quality and audiovisual quality of Internet video and distribution quality television in any environment.” INT, I. [23] was ideal to use due to the fact that we were in an epidemic situation. The guide reflected accurate methods of experimentation in “any environment”, so we designed the experiment remotely with control over the main key technological aspects. There were 36 users who took part in the user study. These users were selected based on multiple qualifications including a degree in computer engineering and multimedia. Along with that, these users had to have perfect vision to take part in the experiment as it was a video-related assessment experiment.

4.1. General Viewing Conditions

The viewing conditions of this experiment will be evaluated based on the user and their screen. The viewing distance was chosen to be the preferred viewing distance (PVD) which was based upon viewers’ preferences. These are the recommendations used for the experiment. Due to the fact that the experiment took place on a remote non-monitored platform, the user was informed before downloading the sample video to change their screen settings to the most default settings and ITU recommendation settings and state the quality feedback of their screen. This way, we had enough information to choose one set of static screen quality and its default options. The user then evaluated their experience in the form of an MOS 5-point scoring system. The MOS ratings helped us identify the user’s preference towards the video and its settings shown in Table 4.

Table 4.

Test Conditions (based on ITU-T recommendation).

4.2. Technical Test Bed Setup

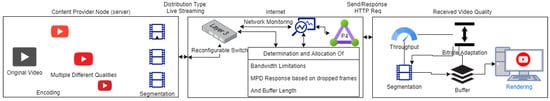

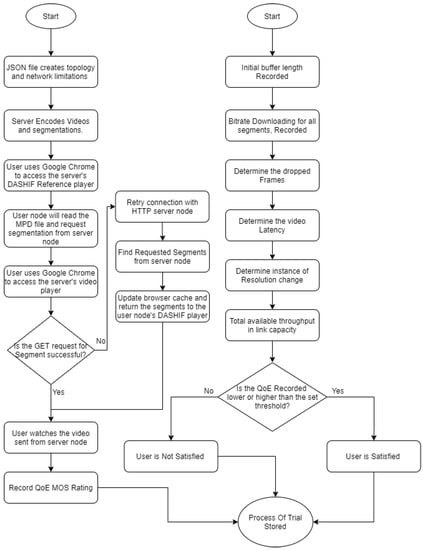

Our test bed was built on an Ubuntu machine running multiple items. The SDN environment was setup on a Mininet virtualisation platform. The network backend was programmed with P4 Language using the aid of P4Runtime API. We extended the basic L3 forwarding with a scaled-down version of in-band network telemetry (INT) to make it simpler to have a multi-hop route inspection. This configuration was completed to make the test bed have universal application of testing multiple virtual devices and/or a single device and a server. This configuration allowed the developer to track the path and the length of queues that every packet traveled through. Multiple issues with normal Openflow configuration arose at this stage [24]; thus the programmability of data plane with P4 helped to append an ID and queue length to the header stack of every packet. At the destination, the sequence of switch IDs corresponded to the path, and each ID was followed by the queue length of the port at switch. With this, a developer will need to define the control plane rules as performed with any Openflow application (but with P4). On top of that, we implemented the data plane logic of the P4 controller. This gave the user the ability to not only monitor one aspect of the network, but all ports, identifying multiple monitoring applications such as congestion which was discussed in one of our previous papers [1]. Furthermore, we created a DASHIF Reference Player Server node on our test bed, and a client host from another part of the network where the client streamed the video segments of the DASH server. Through the network, we monitored all routes and saved all the network data and the reference’s broadcast data to experiment with in machine learning. There were multiple reasons why we avoided having the user testing happen on our virtual platform apart from the global COVID-19 pandemic. After a short time of testing, we realised a noticeable latency delay that was not recorded by the network monitoring techniques that we implemented. This was due to the limitation of the virtual machine. While playing a video, we realised that the machine’s CPU was over-exhausted. Thus, the user MOS rating would be affected by non-network factors which we wanted to eliminate for accurate results by converting the recorded segments into an mp4 file to be downloaded and run by the tester. Figure 2 shows the process of the DASH player live streaming to a user over HTTP send and receive requests and the adaptation of video quality. Figure 3 shows the experimentation process from technical server and client ends. All switches were assigned and defined with an IP address and port numbers known to the development side of the process for data monitoring. Moreover, links were assigned experimental bandwidth limitations on the client’s end to understand the patterns of network flow from the server node and to use them later as support experiments for QoE classification and prediction. Our generated data, even though it was one type of video content (animation video), had network traces that helped us in the creation of multiple predictors and the ability to compare and contrast them to choose the best fit for all future video data [22]. Table 5 shows the experimentation video map and test conditions.

Figure 2.

Testbed overview.

Figure 3.

System test bed process and QoE evaluation.

Table 5.

Experimentation video map and test conditions.

5. Discussion and Data Analysis

5.1. Experiment Plan and Data Description

In this experiment, we used the DASHIF reference player web streaming application for adaptive streaming to users. This was to collect stream properties and understand user response based on quantitative research. Firstly the streaming server streamed selected videos in fixed properties such as a collection of fixed frame-rates, and resolutions based on chosen video segmentation. Fixed network properties controlled the experiment from a network backend perspective; On the web form, there was a MOS rating where the user shared his/her experience. The quantitative questionnaires were limited to a rating from 1 to 5 to reflect the relevant chosen video. All network data was captured from the user, including the questionnaire, screen properties and stream. In addition to server-side streaming properties, data recorded was placed in the processing phase. Then, concluded based on highly impacting features whether a user was satisfied or not. The experiment’s expectation was to outline the correct parameters (such as the manipulation of resolution) that will be used in the next experiment as an editable user choice configuration. A realistic video MPD dataset was generated based on segment collection. This dataset represented a group of MPD manifests and m4s, encoded to run on a DASHIF reference player for dynamic adaptive streaming testing. We then extracted from the manifests seven video features that were our main input to the data training. These included initial buffer length, live buffer length, bit rate downloading, dropped frames, latency, and video resolution with indexing information and three MOS ratings made by every user while they were streaming as shown in Table 6. These features were selected as they are the primary factors that are affected by network performance which can affect the user’s experience; they were all used along with multiple other network monitoring properties and were chosen due to their direct effect on the prediction score. These features along with the network features themselves aided the classifications algorithms to learn and identify the patterns of user satisfaction.

Table 6.

Generated dataset.

Furthermore, our training data consisted of multiple properties that made them precise and unique. For the lowest network limitations that were implemented, the downloading bit rates ranged from 45,373 to 88,482 bps with a noticeable initial loading delay that averaged out to be around 2.4 s. Medium networking runs provided a better range of downloading bit rate, averaging around 317,328 bps and 1.58 s of initial load delay. Finally, when the network was given a bit more space and room to work, the data showed an approximate bit rate download of 2,147,880 bps and 1.3 s of initial loading delay. This is expressed in Table 7 for a clearer view. It is also important to know that the test bed was engineered to monitor the effects of network congestion on the quality of experience. This study shows the process of training the output data first to understand and generate a predicted MOS based on the trained model, increasing the ease of analysis of applications and tests that require MOS prediction within the test bed without the need for more human ratings.

Table 7.

Experiment ranges.

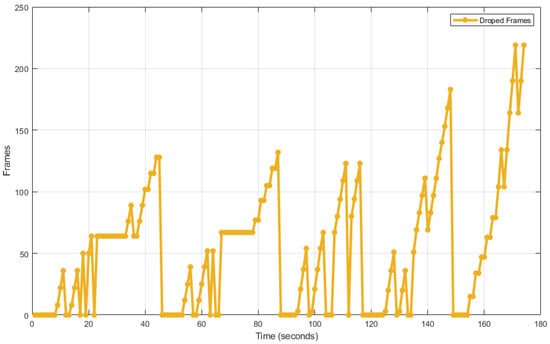

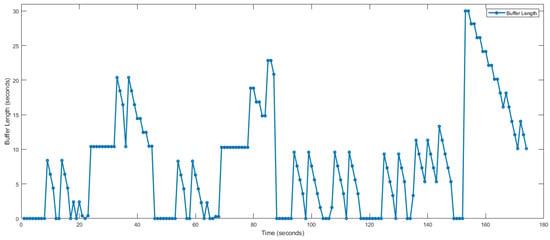

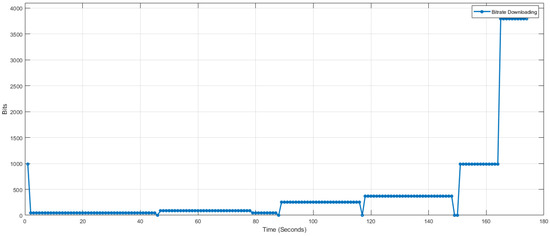

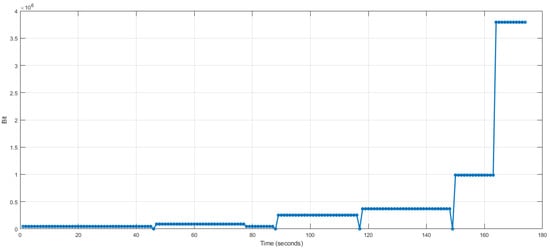

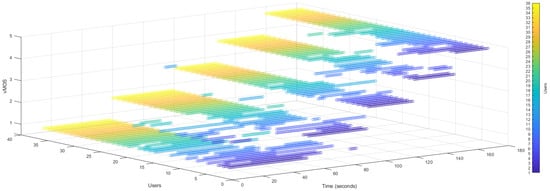

Figure 4, Figure 5, Figure 6 and Figure 7 show the bit rate downloading, resolution, dropped frames, and buffer length. Figure 8 shows the vMOS of the users on a 3D scatter plot where the X-Axis shows the time frame, the Y-Axis shows the users who participated, and the Z-Axis shows the MOS ratings. This figure explains the number of recorded responses, and we can see the direct relation of the network features to the MOS and the time frame of uploading. It seems that the data present a logical front of an increase in performance that directly leads to an increase in vMOS for the quality preserved by the users. These figures conclude that our chosen features directly satisfy our data generation for training-ready data as they show a linear increase in QoE as the network feature abilities are less restricted.

Figure 4.

Results of dropped frames network feature experimentation trials.

Figure 5.

Results of buffer length network feature experimentation trials.

Figure 6.

Results of bit rate downloading network feature experimentation trials.

Figure 7.

Results of resolution network feature experimentation trials.

Figure 8.

Results of vMOS experimentation trials.

5.2. Machine Learning Classification

Furthermore, a data analysing process had to happen on two different levels after obtaining raw data from the virtual test bed and the vMOS from the users. QoE scoring factors and network data had to go through data cleaning and normalisation. Then, the features stated before were placed through a training process against the MOS and vice versa to make a collection of classification predictions and use a neural network to compare and contrast them. All features were trained with fine tree, medium tree, coarse tree, kernel naive Bayes, linear SVM, quadratic SVM, cubic SVM, fine Gaussian SVM, medium gaussian SVM, fine KNN, medium KNN, coarse KNN, cosine KNN, cubic KNN, weighted KNN, boosted trees, bagged trees, subspace discriminant, subspace KNN and RUSBoosted trees. With no over-trained attempts, which model is best fitted for the data and the feature classified [22] by comparing and contrasting. Figure 9 shows an example of the data analysis process.

Figure 9.

Data analysis.

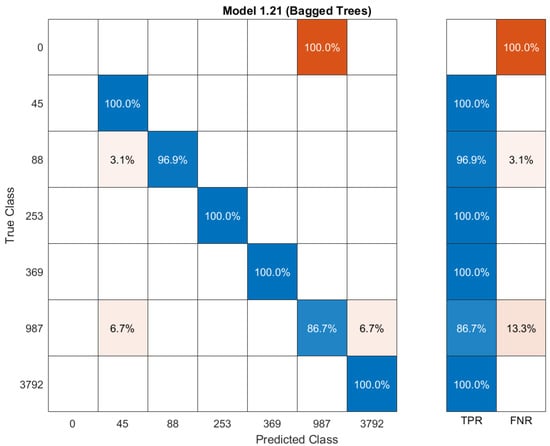

In Table 8, all classification methods mentioned above are used to classify the five features and predict their outcome if a new stream of data is inserted. The table shows the percentage of the predicted class against true class. From these models, the researcher selected the models with the highest accuracy along with the fastest prediction time. Bagged trees was selected for bit rate downloading and MOS and fine KNN for the buffer length, the dropped frames and the resolution. Table 9 shows the most ideal machine learning classification prediction methods on highly noisy data, such as our generated network data and MOS user feedback technique proposed in our previous paper [22]. It is important here to discuss the prediction speed along with the training time for the prediction of MOS. The training time, prediction speed and misclassification cost columns are representations of the different machine learning classifications to predict MOS. The highest accuracy using bagged trees resulted in 10.69 s with 1200 observations processed per second. This is a good presentation to see in the live test bed.

Table 8.

Comparing classification metrics across all features.

Table 9.

Resulting machine learning prediction methods on noisy network training data.

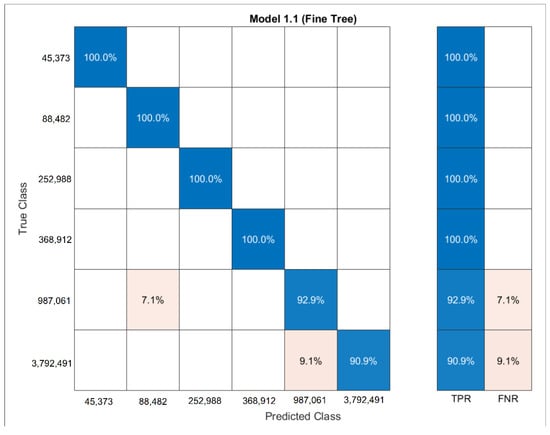

5.3. Models Description and Neural Network

As described earlier, for each architecture we tried different hyper-parameters to see the best fit for the proposal. More precisely, we varied the following: 1. the use of cross-validation folds to protect against overfitting by partitioning the dataset into folds and estimating accuracy on each fold (from 2 to 50 folds); 2. number and types of splits (diversity indexes, surrogate decision splits); 3. training algorithm; 4. number of layers in a network; and 5. number of neurons for a layer. A total of 30% of our data was randomly taken out of the training phase to use for validation. Ultimately, we considered the classification of all features and their classes as shown in Table 8 and the use of a neural network on MOS prediction using the Bayesian regularization with 2 layers and 10 neurons, using mean squared error for performance rating. This resulted in a 0.999 regression value which means that the correlation between the output and the target is highly accurate. So, after comparing and contrasting the classification metrics used, we recommend the mentioned models above for each one of the features as an accurate prediction method. The study shows that these models are quite accurate when it comes to DASH-related streaming data and real user MOS. The neural network method with the selected options stated above tend to be more accurate towards small or noisy datasets. However, it takes more time and computing power and will be inefficient to be placed within a test bed for auto prediction and redirection of resources. For such noisy data, prediction methods must be tested and uniquely selected for the prediction of each and every feature that is dependent on all other features, Figure 10 shows the framework bit rate precision result after choosing bagged trees, whereas Figure 11 shows the framework’s resolution prediction results after choosing fine tree. The main takeaway from these two figures is to show the differences between the two methods on the same data. This helps our research by identifying and reading correctly predicted true classes and how the methods react to noisy data such as ours.

Figure 10.

Framework bit rate prediction results.

Figure 11.

Framework resolution prediction results.

5.4. State-of-the-Art Comparison Discussion

It is quite difficult to compare our framework to other state-of-the-art solutions due to its multiple different outputs. However, there are some solutions that provide parts similar to some of our outcomes. These are listed in Table 10. SDNDASH [25,26] focuses on QoE requirements to build an SDN-based management and resource allocation system to maximize the quality perceived; However, their solutions do not consider the network data as a straight feature contribution for direct prediction. Our approach focuses on using network data to automatically predict the QoE of a real user. With multiple network configurations, our predicted features and QoE reached new heights on known classifiers. SDNDASH focuses on a single user and recommends a certain bit rate and buffer levels, where our framework comes with pre-designed adjustable network features and shows the developers how each feature affects the QoE on a human level, thus eliminating testing with users. Another solution [27] proposed a network application controller called service manager, which reads video traffic and allocates resources fairly among competing congestion. Our solution has elements of this step and shows the user the best segments with the most optimal resolution for their network configuration. The higher the configuration, the better the quality perceived and shown on the classifiers will be. A similar state-of-the-art solution [25] offers a caching technique where users are informed of the cache’s content as well as a short-term prediction of the bottleneck bandwidth, whereas our framework shows prediction for the entire duration of the segmented perceived file. QFF [28] proposed an open-flow-assisted QoE framework with optimizing QoE among HAS clients with heterogeneous device requirements. This is ideal because the device information can limit the allocation to certain devices and save the rest for devices that require more bandwidth. Our test bed is missing this functionality, and it can be useful to adapt it. Our framework can produce training-ready data; thus, this can be an addition in future work to enhance the test bed. However, it will not affect the prediction due to the fact that the prediction is based purely on network features.

Table 10.

State of Art Comparison.

6. Conclusions

This research concludes by answering and researching multiple questions about quality of experience and its prediction. Firstly, we aimed to ease the replication of this research by building a new simulation environment for future researchers in similar fields. This simulation is able to run both P4 and Openflow, along with Python 2 and 3 instances, DASH and Mininet. With all essential packages installed, an error-free test environment for running this and other related experiments and applying previous and similar work to compare and contrast results is installed. Furthermore with this build, a P4 SDN test bed over Mininet was designed with the ability to control DASH initial buffering, stalling, switching, monitoring, bit rate adaptation and bandwidth limitation over selected ports. The test bed provides the capacity for comprehensive user experiments and data collections, which lead to our insights and analysis of congestion for congestion-related experiments, along with full re-configurability over data plane. This being an open-source project clears the difficulties and eases the research methodology into media streaming applications, tests and experiments. Was it possible to create a hybrid environment for testing on a user level and predicting with machine learning with simply inserting the network or user feedback data to generate the other? With this open-source project, we cleared that hurdle. Moreover, we proposed an experimentation framework structure through programmable network management for the generation of ML training-ready data and MOS/QoE prediction with the aid of a human experiment with QoE MOS-based feedback to benchmark the accuracy of the predicted QoE and network features. Our analysis of state-of-the-art machine learning algorithms, along with the creation of our framework for feature evaluation in network experiments is unique in its attribute and network design; however, it is reprogrammable to match any type of media experimentation. Understanding user-effective network data has become as crucial as the QoE on individual user devices. This paper discusses different features of network-level experimentation and the prediction of QoE in multimedia applications. We also discussed how perceivable QoE is linked to resource allocation and traffic engineering at the network level and how emerging programmable networks such as SDN can be used as a tool to improve user feedback and how that data can be used to predict human feedback. An automated data collection and prediction framework is also proposed to harness the capabilities of new network designs and growing availability of computing resources in future networks for fairness-aware content distribution. As shown in Table 8, the ML classification methods are used and compared for the features that are used for prediction. We conclude that our generated dataset and experimentation framework can support the development of a high-accuracy machine learning model for QoE estimation. The use of existing neural networks also proved effective with our data but consumed more computational power and time as mentioned in the previous section. Our future work will look into implementations of this QoE/MOS predictor in a live smart home environment.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.O.B.A.-M.; methodology, A.O.B.A.-M.; software, A.O.B.A.-M.; validation, A.O.B.A.-M.; formal analysis, A.O.B.A.-M.; investigation, A.O.B.A.-M.; resources, A.O.B.A.-M.; data curation, A.O.B.A.-M.; writing—original draft preparation, A.O.B.A.-M.; writing—review and editing, A.O.B.A.-M.; visualization, A.O.B.A.-M.; supervision, M.M. and A.A.-S.; project administration, A.O.B.A.-M.; funding acquisition, A.O.B.A.-M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work is supported by UK Research and Innovation (UKRI) under EPSRC Grant EP/P033202/1(SDCN).

Data Availability Statement

Datasets, analysied and raw collections along with technical setups can be found here: https://github.com/AhmedOsamaBasil/PhD (accessed on 3 August 2022).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Basil, A.O.; Mu, M.; Al-Sherbaz, A. A Software Defined Network Based Research on Fairness in Multimedia. In FAT/MM ’19, Proceedings of the 1st International Workshop on Fairness, Accountability, and Transparency in MultiMedia, Nice, France, 25 October 2019; ACM: New York, NY, USA, 2019; pp. 11–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ke, C.H. P4: Switch: MAC Layer and IP Layer Forwarding. Library of P4 Resources. 2015. Available online: http://csie.nqu.edu.tw/smallko/sdn/p4_forwarding.htm (accessed on 1 October 2018).

- Alsaeedi, M.; Mohamad, M.M.; Al-Roubaiey, A.A. Toward Adaptive and Scalable OpenFlow-SDN Flow Control: A Survey. IEEE Access 2019, 7, 107346–107379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basil, A.O. Experimenation Datasets and Algorithms. 2022. Available online: https://github.com/AhmedOsamaBasil/PhD (accessed on 24 May 2019).

- Yousef, H.; Feuvre, J.L.; Storelli, A. ABR prediction using supervised learning algorithms. In Proceedings of the 2020 IEEE 22nd International Workshop on Multimedia Signal Processing (MMSP), Tampere, Finland, 21–24 September 2020; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sani, Y.; Raca, D.; Quinlan, J.J.; Sreenan, C.J. SMASH: A Supervised Machine Learning Approach to Adaptive Video Streaming over HTTP. In Proceedings of the 2020 Twelfth International Conference on Quality of Multimedia Experience (QoMEX), Athlone, Ireland, 26–28 May 2020; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, H.; Netravali, R.; Alizadeh, M. Neural Adaptive Video Streaming with Pensieve. In SIGCOMM ’17, Proceedings of the Conference of the ACM Special Interest Group on Data Communication, Los Angeles, CA, USA, 21–25 August 2017; Association for Computing Machinery: New York, NY, USA, 2017; pp. 197–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, Z.; Chen, J.; Guo, Y.; Sun, C.; Hu, H.; Xu, M. PiTree: Practical Implementation of ABR Algorithms Using Decision Trees. In MM ’19, Proceedings of the 27th ACM International Conference on Multimedia, Nice, France, 21–25 October 2019; Association for Computing Machinery: New York, NY, USA, 2019; pp. 2431–2439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Y.; Song, L.; Xie, R.; Zhang, W. SJTU 4K video subjective quality dataset for content adaptive bit rate estimation without encoding. In Proceedings of the 2016 IEEE International Symposium on Broadband Multimedia Systems and Broadcasting (BMSB), Nara, Japan, 1–3 June 2016; pp. 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moorthy, A.K.; Choi, L.K.; Bovik, A.C.; de Veciana, G. Video Quality Assessment on Mobile Devices: Subjective, Behavioral and Objective Studies. IEEE J. Sel. Top. Signal Process. 2012, 6, 652–671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.; Choi, L.K.; de Veciana, G.; Caramanis, C.; Heath, R.W.; Bovik, A.C. Modeling the Time—Varying Subjective Quality of HTTP Video Streams With Rate Adaptations. IEEE Trans. Image Process. 2014, 23, 2206–2221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ghadiyaram, D.; Bovik, A.C.; Yeganeh, H.; Kordasiewicz, R.; Gallant, M. Study of the effects of stalling events on the quality of experience of mobile streaming videos. In Proceedings of the 2014 IEEE Global Conference on Signal and Information Processing (GlobalSIP), Atlanta, GA, USA, 3–5 December 2014; pp. 989–993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duanmu, Z.; Zeng, K.; Ma, K.; Rehman, A.; Wang, Z. A Quality-of-Experience Index for Streaming Video. IEEE J. Sel. Top. Signal Process. 2017, 11, 154–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bampis, C.G.; Li, Z.; Moorthy, A.K.; Katsavounidis, I.; Aaron, A.; Bovik, A.C. Study of Temporal Effects on Subjective Video Quality of Experience. IEEE Trans. Image Process. 2017, 26, 5217–5231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duanmu, Z.; Rehman, A.; Wang, Z. A Quality-of-Experience Database for Adaptive Video Streaming. IEEE Trans. Broadcast. 2018, 64, 474–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lederer, S.; Mueller, C.; Timmerer, C. Dynamic adaptive streaming over HTTP dataset. In Proceedings of the 3rd Multimedia Systems Conference, Chapel Hill, NC, USA, 22–24 February 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Ben Letaifa, A. Adaptive QoE monitoring architecture in SDN networks: Video streaming services case. In Proceedings of the 2017 13th International Wireless Communications and Mobile Computing Conference (IWCMC), Valencia, Spain, 26–30 June 2017; pp. 1383–1388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Delaney, D.T. QoE Oriented Cognitive Network Based on Machine Learning and SDN. In Proceedings of the 2019 IEEE 11th International Conference on Communication Software and Networks (ICCSN), Chongqing, China, 12–15 June 2019; pp. 678–681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abar, T.; Ben Letaifa, A.; El Asmi, S. Machine learning based QoE prediction in SDN networks. In Proceedings of the 2017 13th International Wireless Communications and Mobile Computing Conference (IWCMC), Valencia, Spain, 26–30 June 2017; pp. 1395–1400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abar, T.; Letaifa, A.B.; Asmi, S.E. Real Time Anomaly detection-Based QoE Feature selection and Ensemble Learning for HTTP Video Services. In Proceedings of the 2019 7th International conference on ICT Accessibility (ICTA), Hammamet, Tunisia, 13–15 December 2019; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Issa, A.E.; Bentaleb, A.; Barakabitze, A.A.; Zinner, T.; Ghita, B. Bandwidth Prediction Schemes for Defining Bitrate Levels in SDN-enabled Adaptive Streaming. In Proceedings of the 2019 15th International Conference on Network and Service Management (CNSM), Halifax, NS, Canada, 21–25 October 2019; pp. 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basil, A.O.; Mu, M.; Al-Sherbaz, A. Novel Quality of Experience Experimentation Framework Through Programmable Network Management. In Proceedings of the 2022 IEEE 19th Annual Consumer Communications Networking Conference (CCNC), Las Vegas, NV, USA, 8–11 January 2022; pp. 485–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- INT, I. P.913: Methods for the Subjective Assessment of Video Quality, Audio Quality and Audiovisual Quality of Internet Video and Distribution Quality Television in Any Environment. 2021. Available online: https://www.itu.int/rec/T-REC-P.913-202106-P/en (accessed on 13 June 2022).

- Goto, S.; Shibata, M.; Tsuru, M. Dynamic optimization of multicast active probing path to locate lossy links for OpenFlow networks. In Proceedings of the 2020 International Conference on Information Networking (ICOIN), Barcelona, Spain, 7–10 January 2020; pp. 628–633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhat, D.; Rizk, A.; Zink, M.; Steinmetz, R. Network Assisted Content Distribution for Adaptive Bitrate Video Streaming. In MMSys’17, Proceedings of the 8th ACM on Multimedia Systems Conference, Taipei Taiwan, 20–23 June 2017; Association for Computing Machinery: New York, NY, USA, 2017; pp. 62–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bentaleb, A.; Begen, A.C.; Zimmermann, R.; Harous, S. SDNHAS: An SDN-Enabled Architecture to Optimize QoE in HTTP Adaptive Streaming. IEEE Trans. Multimed. 2017, 19, 2136–2151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kleinrouweler, J.W.; Cabrero, S.; Cesar, P. Delivering Stable High-Quality Video: An SDN Architecture with DASH Assisting Network Elements. In MMSys ’16, Proceedings of the 7th International Conference on Multimedia Systems, Klagenfurt, Austria, 10–13 May 2016; Association for Computing Machinery: New York, NY, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhattacharyya, R.; Bura, A.; Rengarajan, D.; Rumuly, M.; Xia, B.; Shakkottai, S.; Kalathil, D.; Mok, R.K.P.; Dhamdhere, A. QFlow: A Learning Approach to High QoE Video Streaming at the Wireless Edge. IEEE/ACM Trans. Netw. 2022, 30, 32–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liotou, E.; Samdanis, K.; Pateromichelakis, E.; Passas, N.; Merakos, L. QoE-SDN APP: A Rate-guided QoE-aware SDN-APP for HTTP Adaptive Video Streaming. IEEE J. Sel. Areas Commun. 2018, 36, 598–615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).