Nonlinear Combined Resonance of Thermo-Magneto-Electro-Elastic Cylindrical Shells

Abstract

1. Introduction

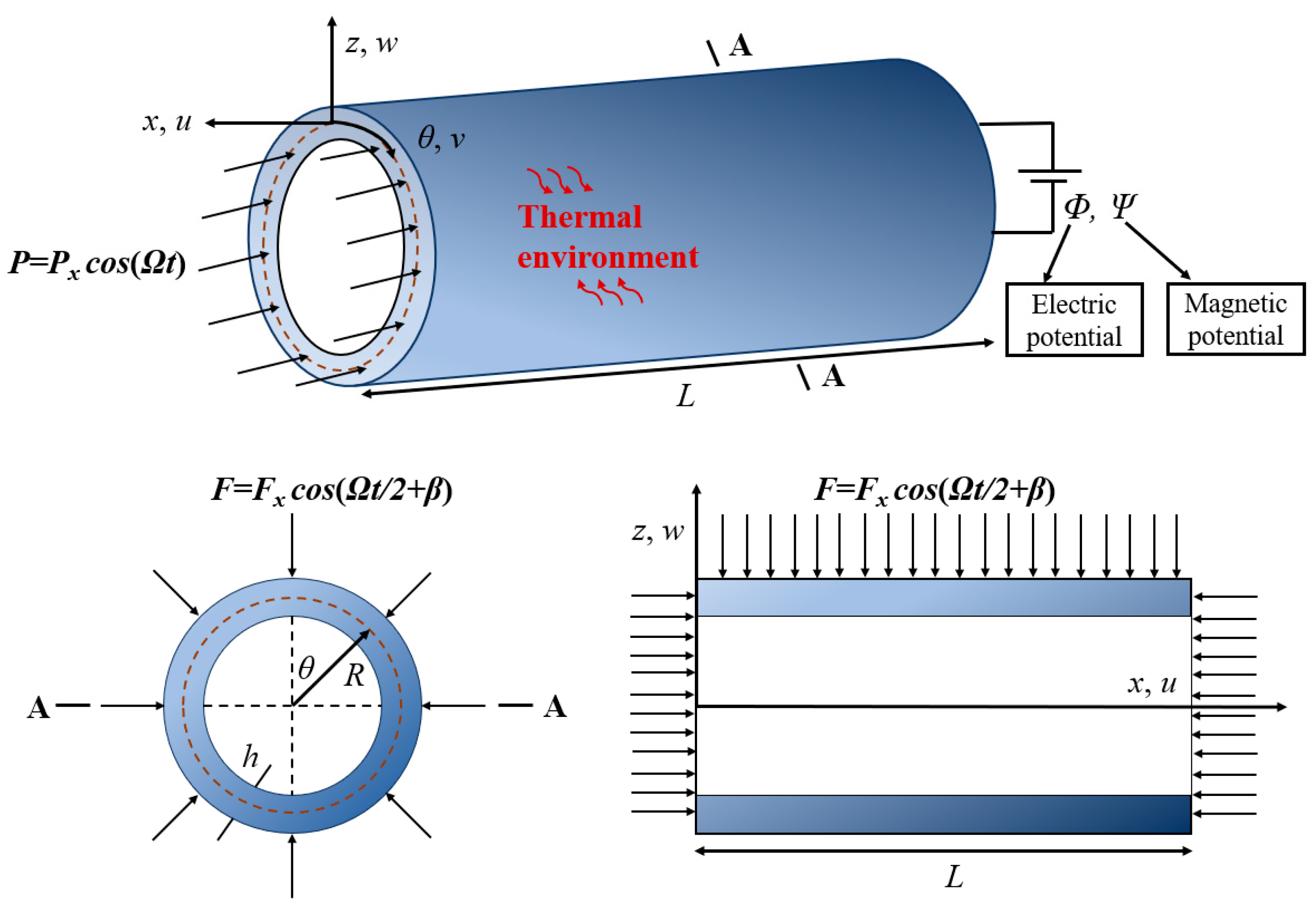

2. Theoretical Models

3. Solution Method

4. Results

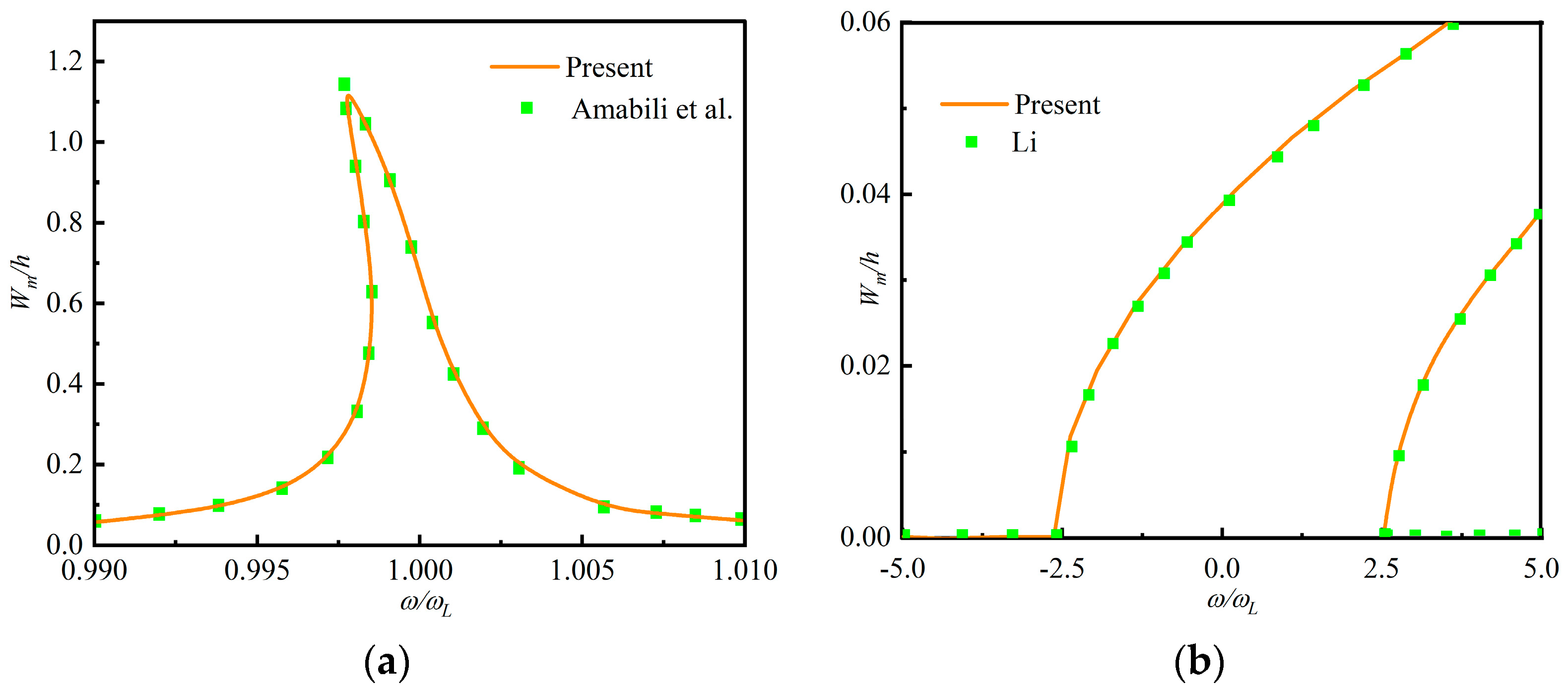

4.1. Comparative Analysis

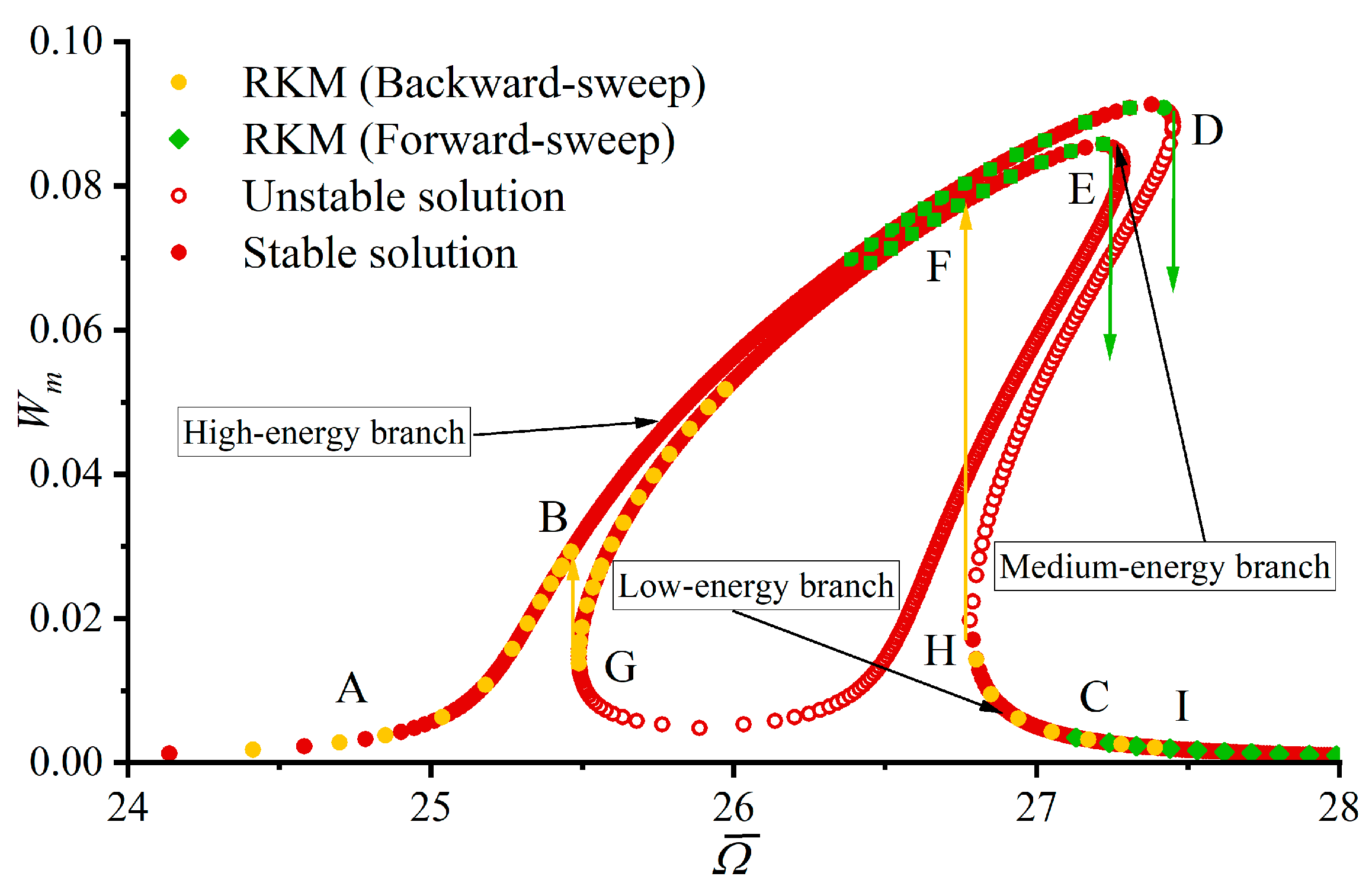

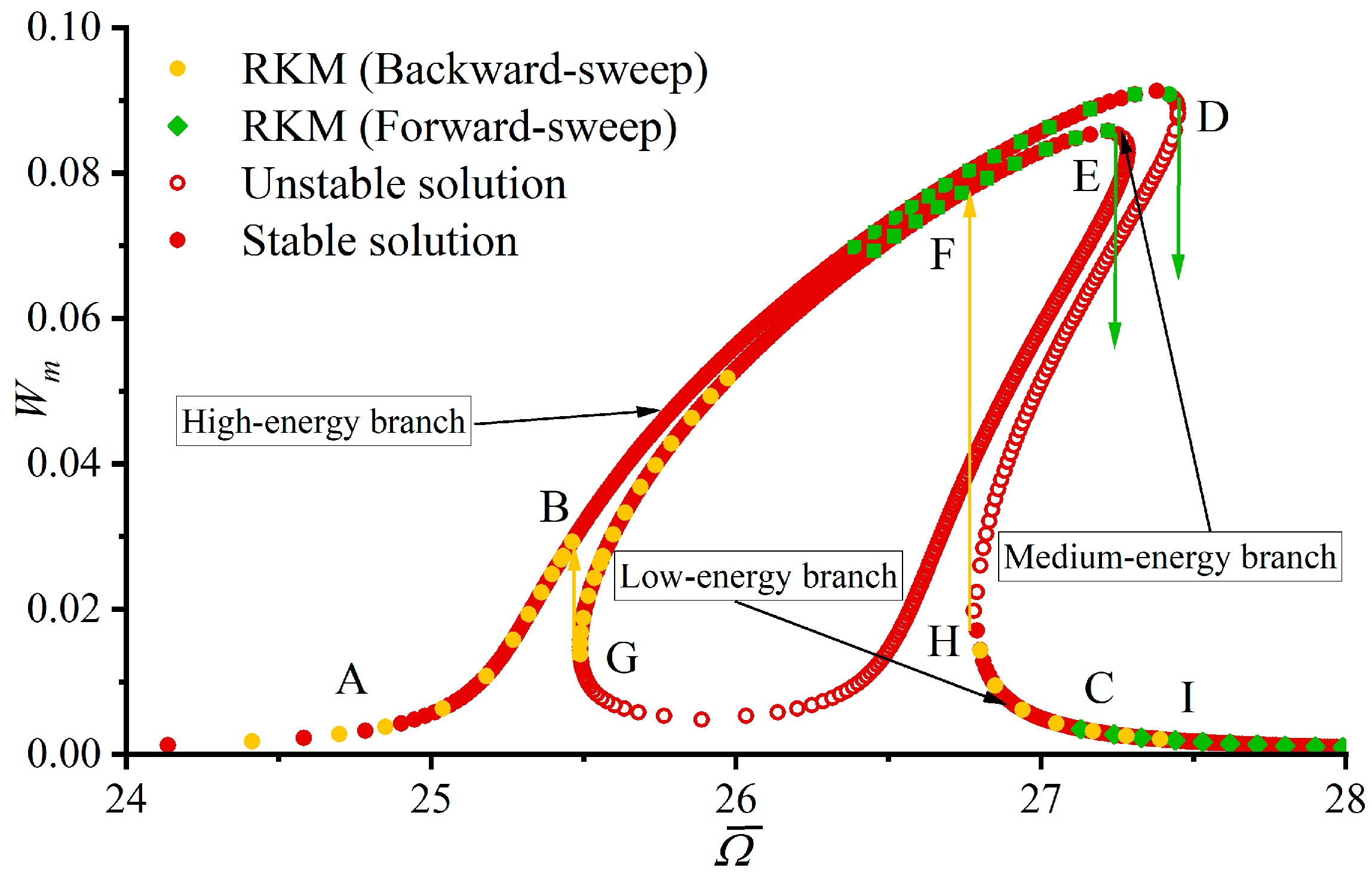

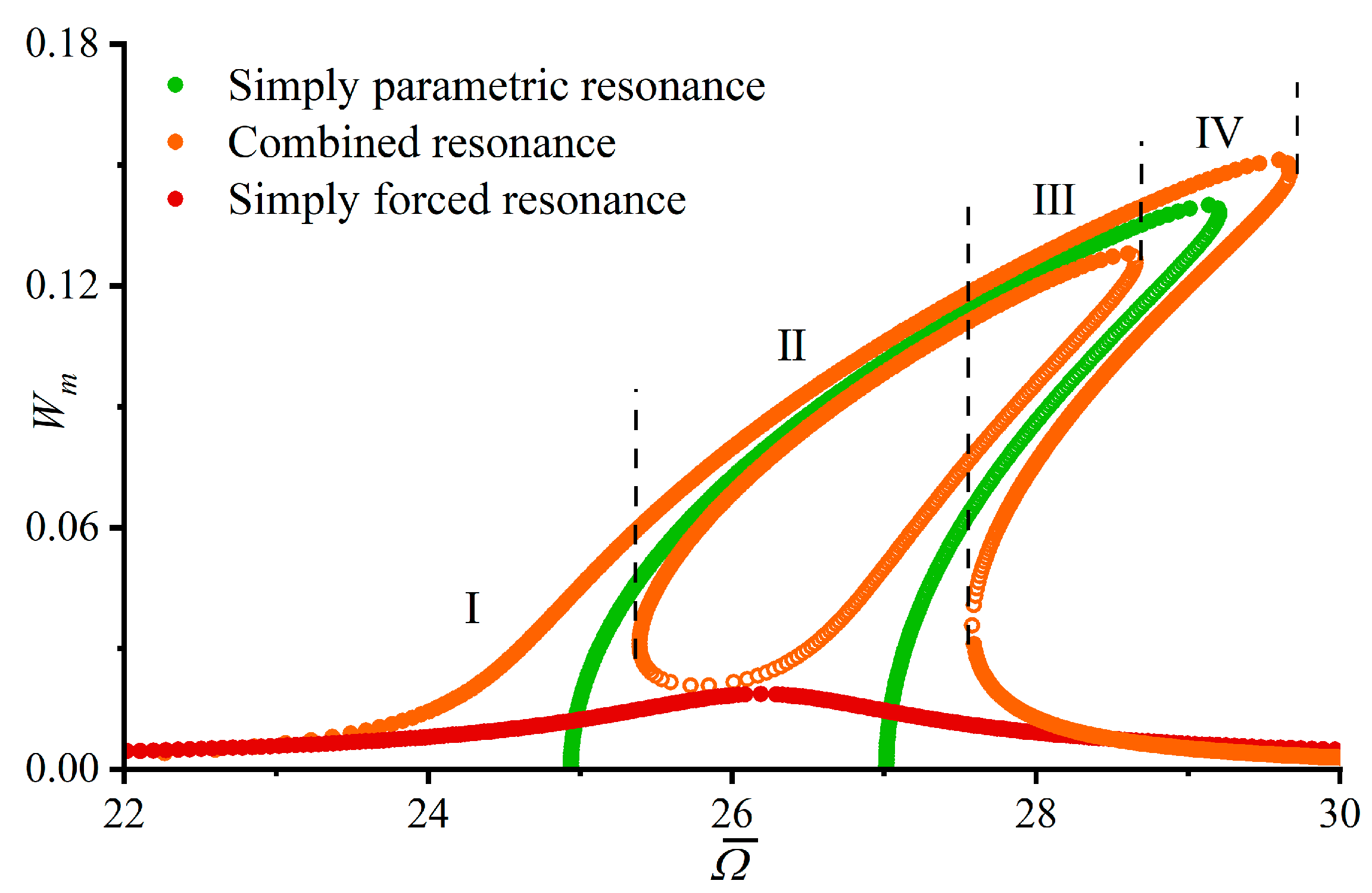

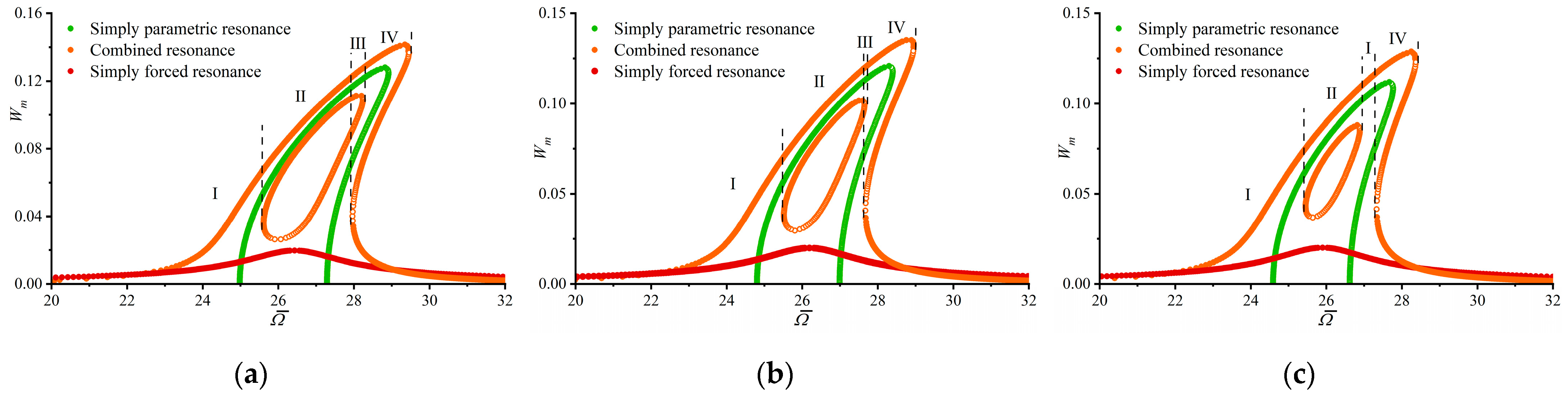

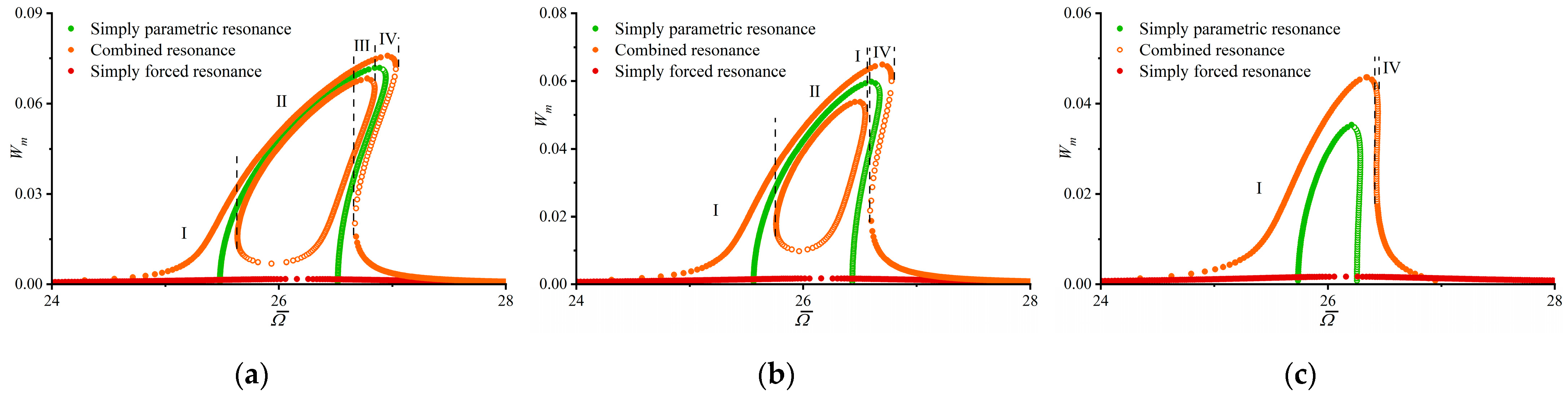

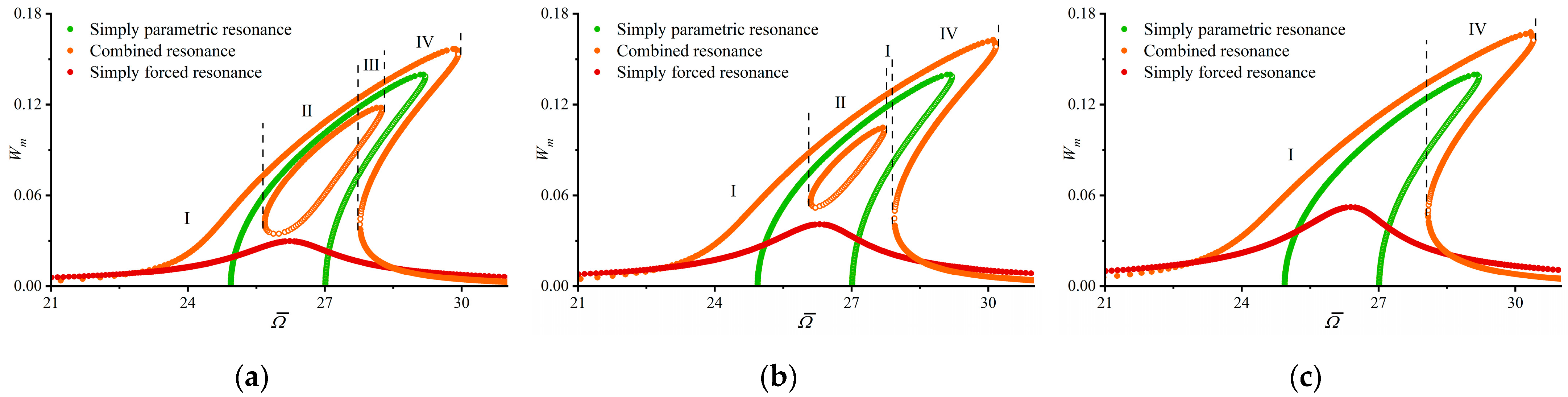

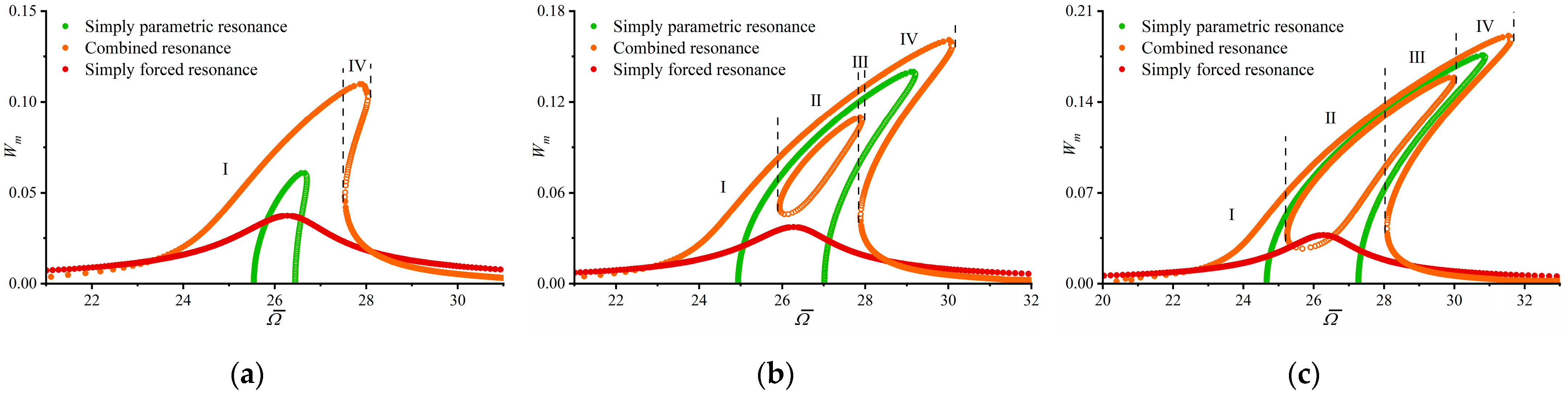

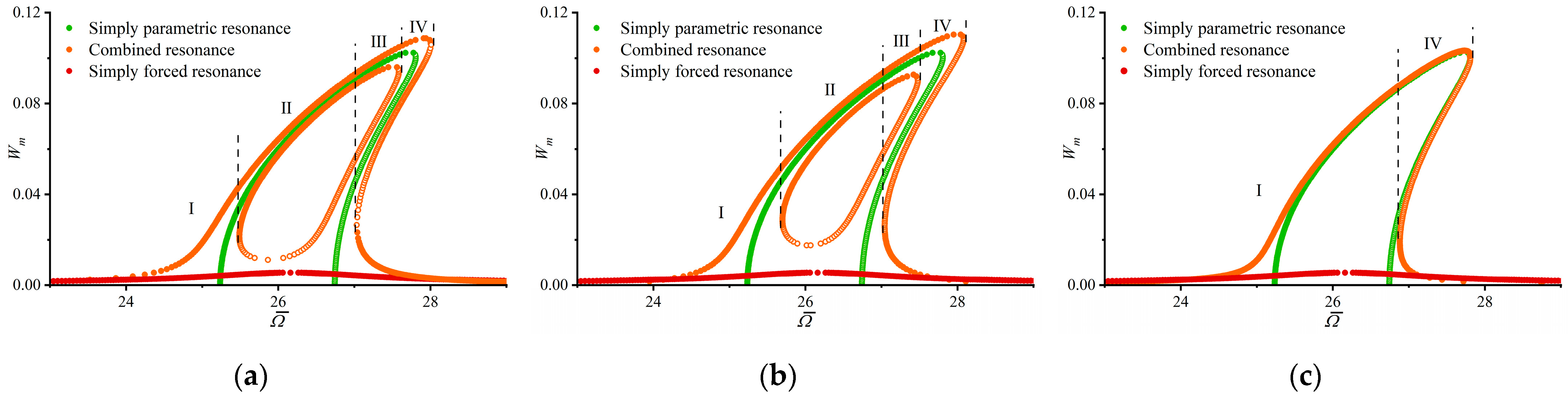

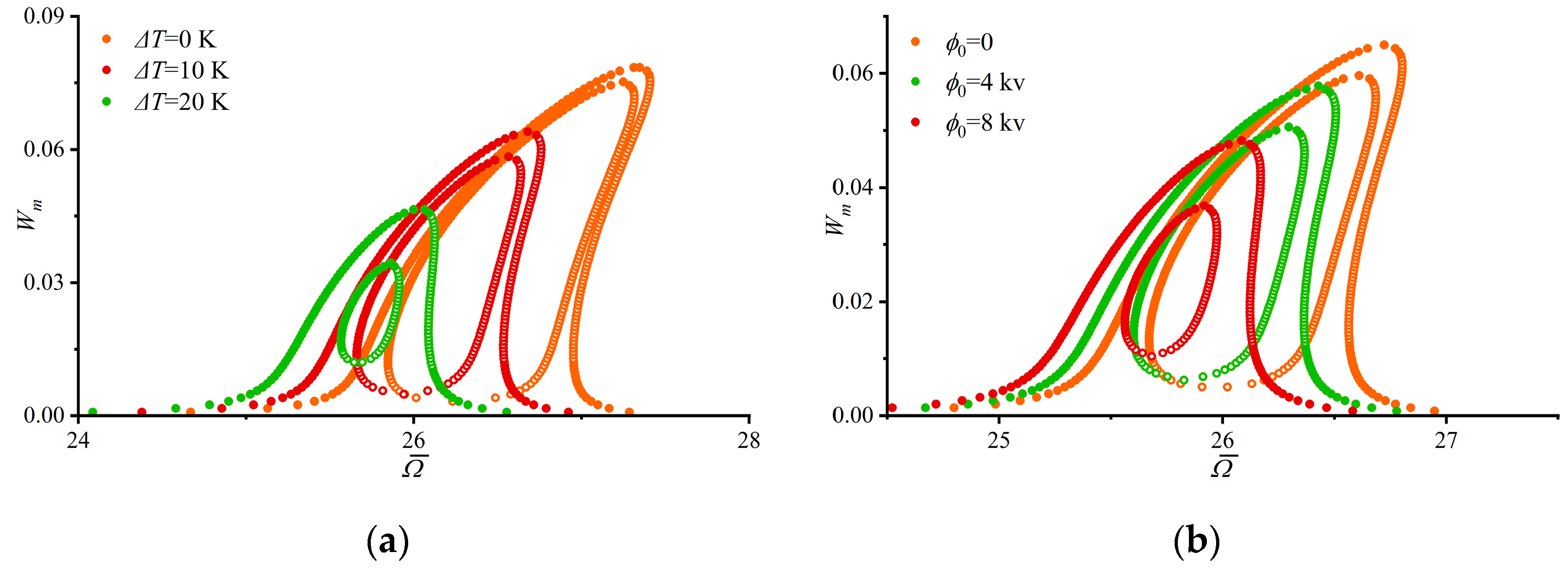

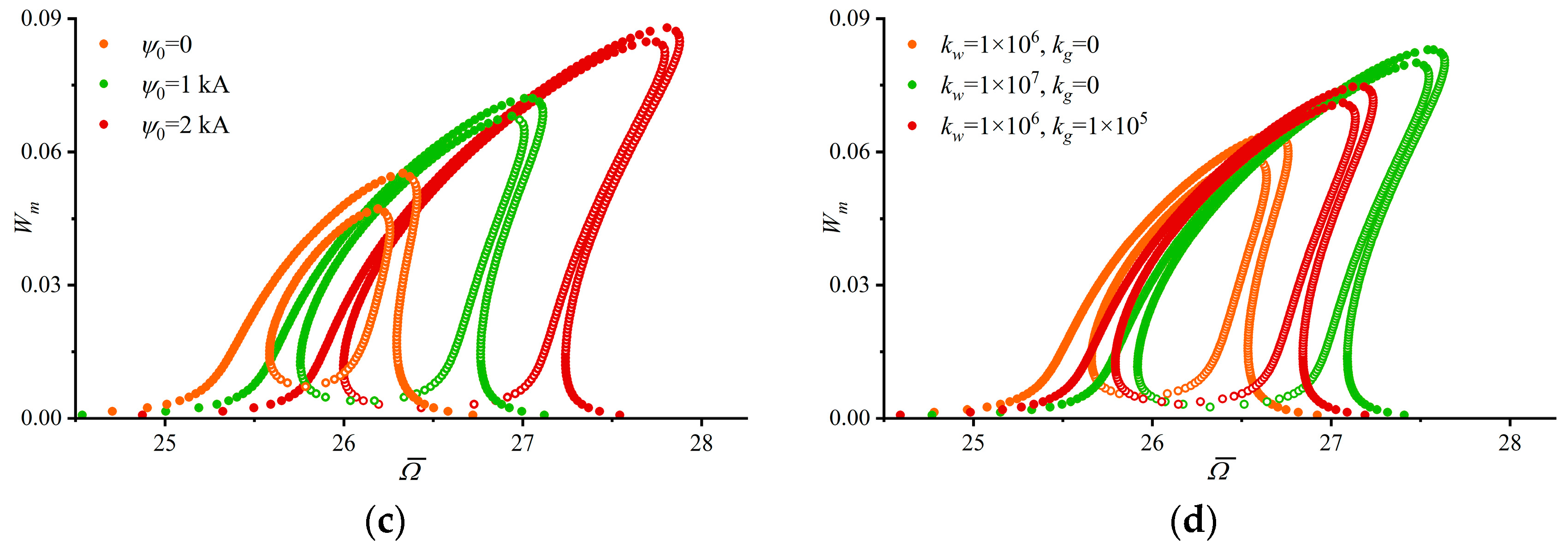

4.2. Parametric Analysis

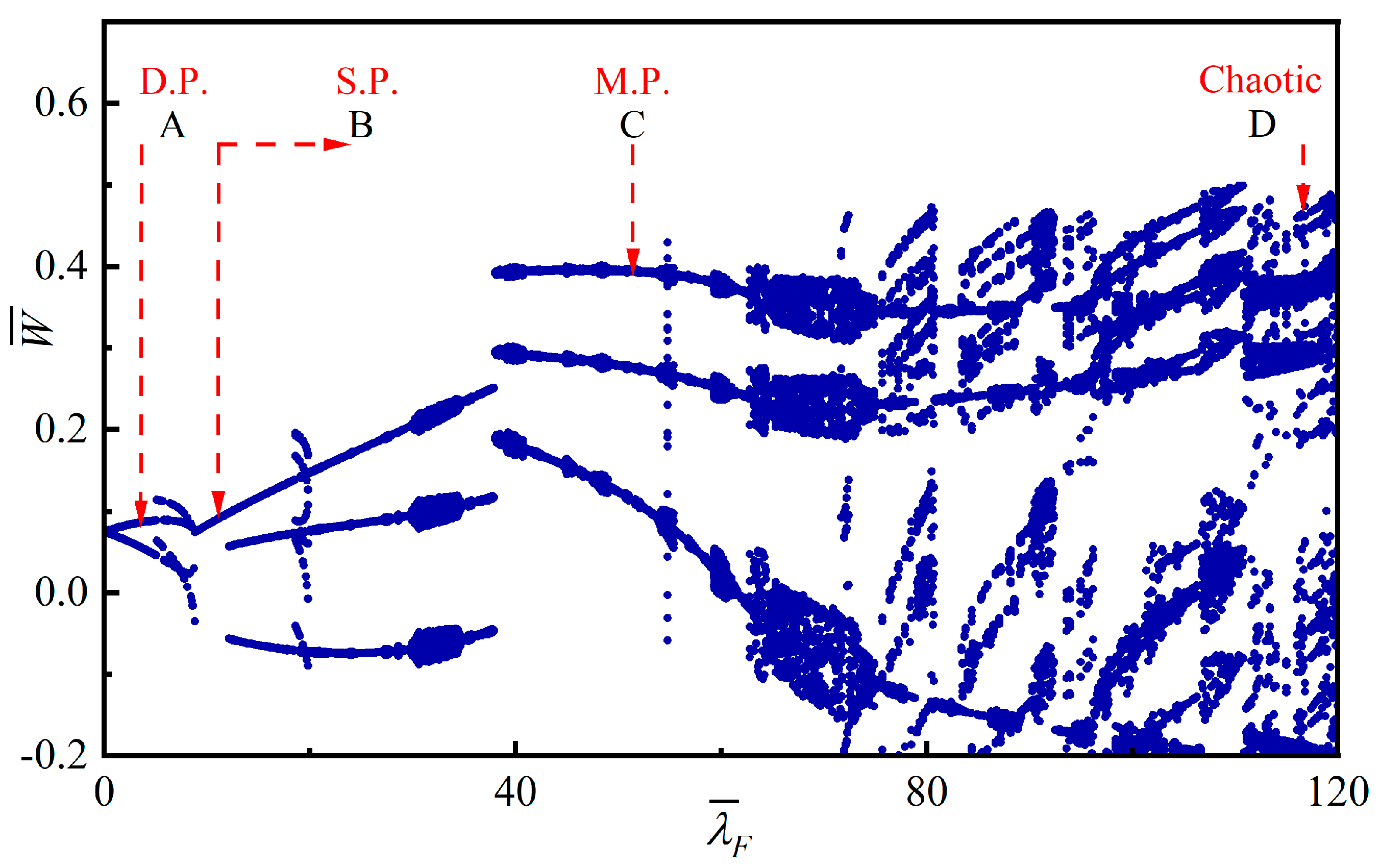

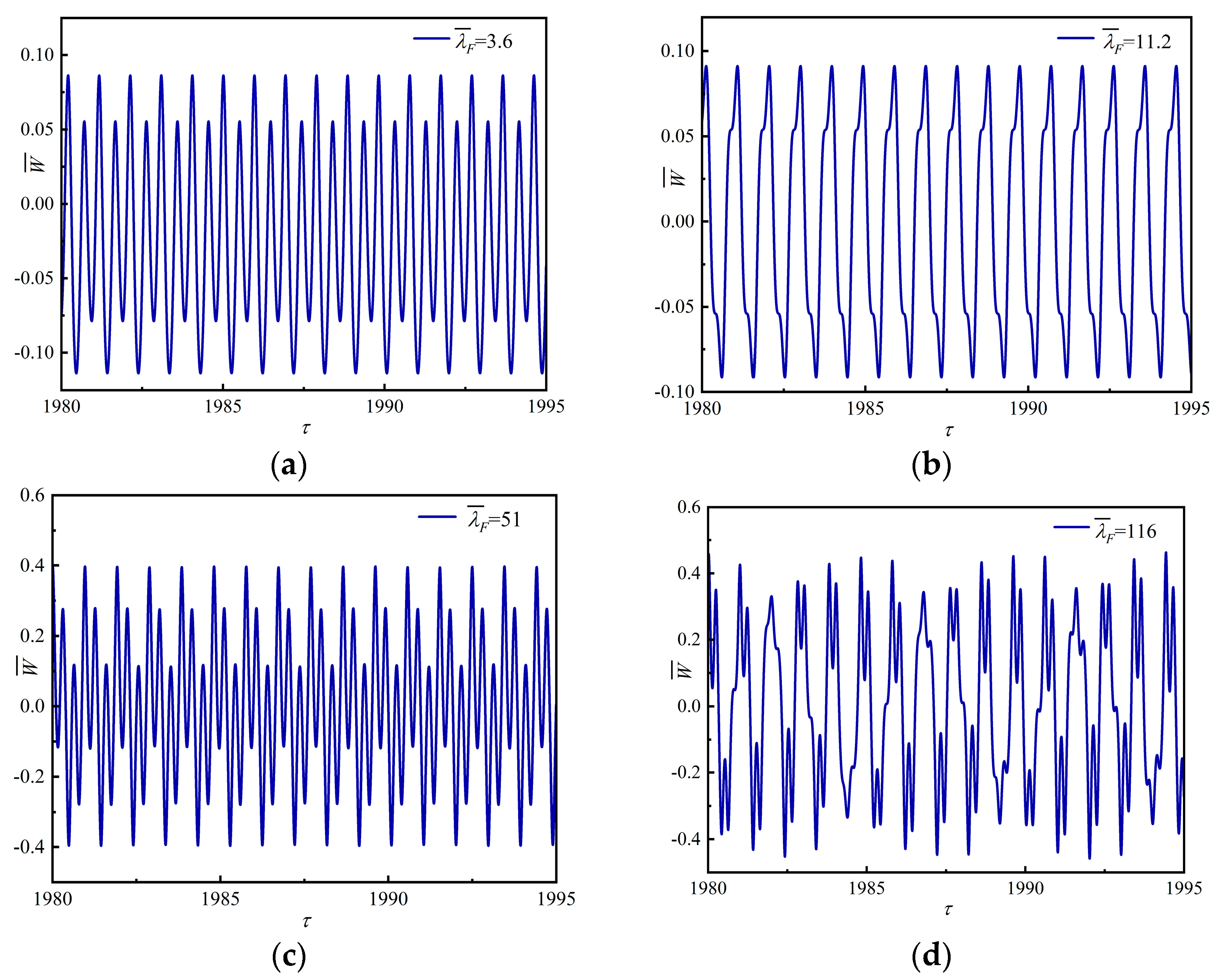

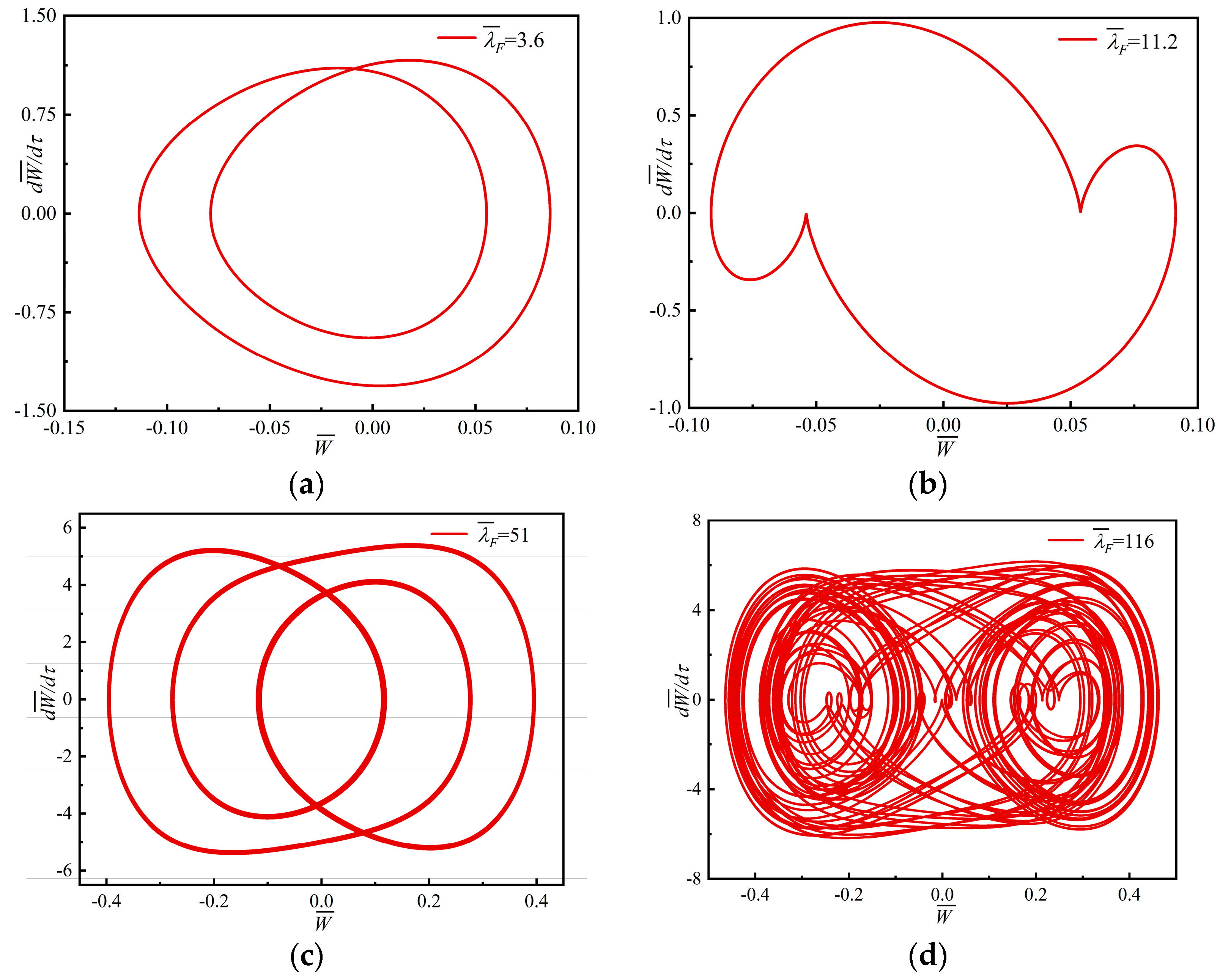

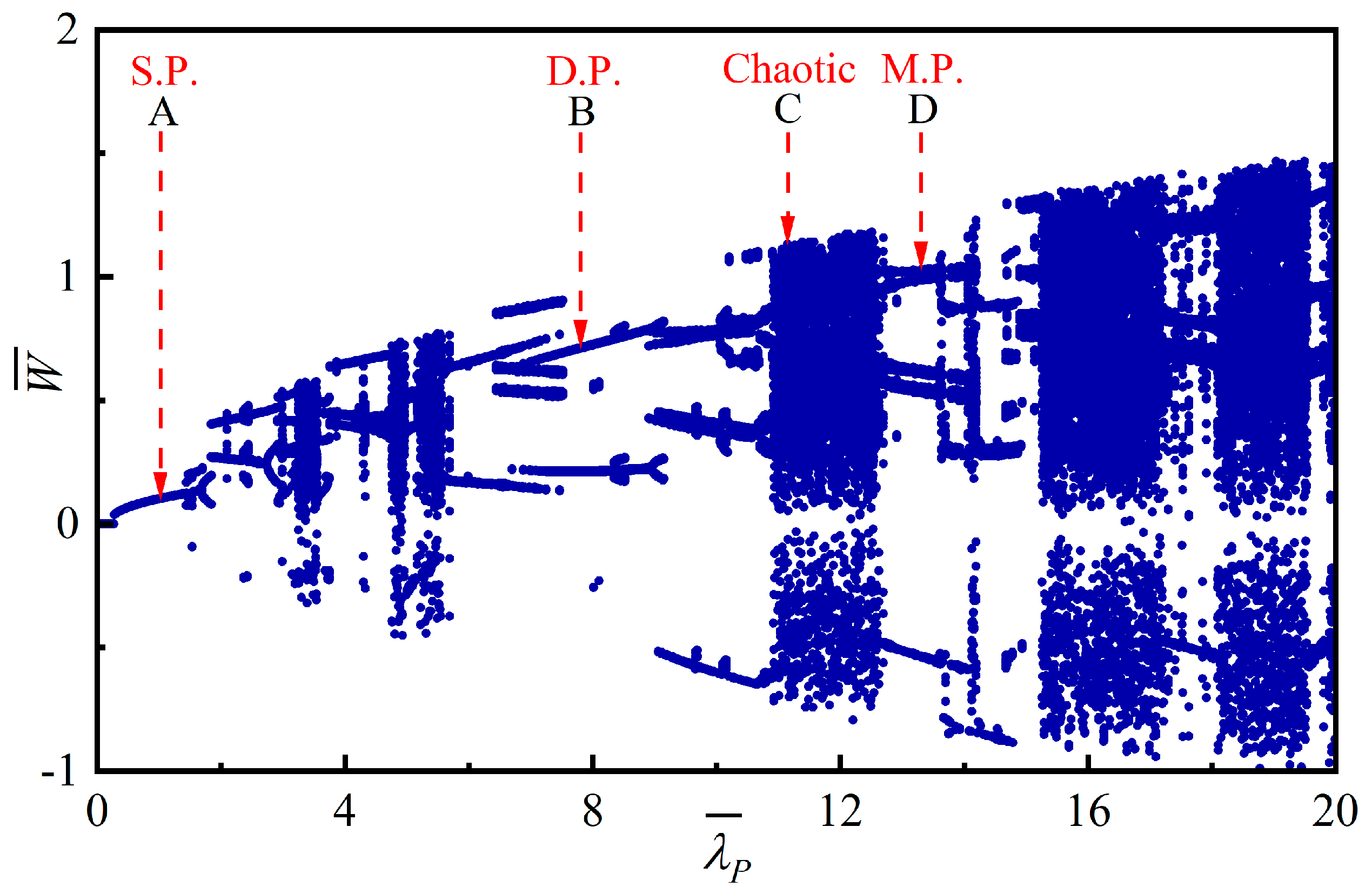

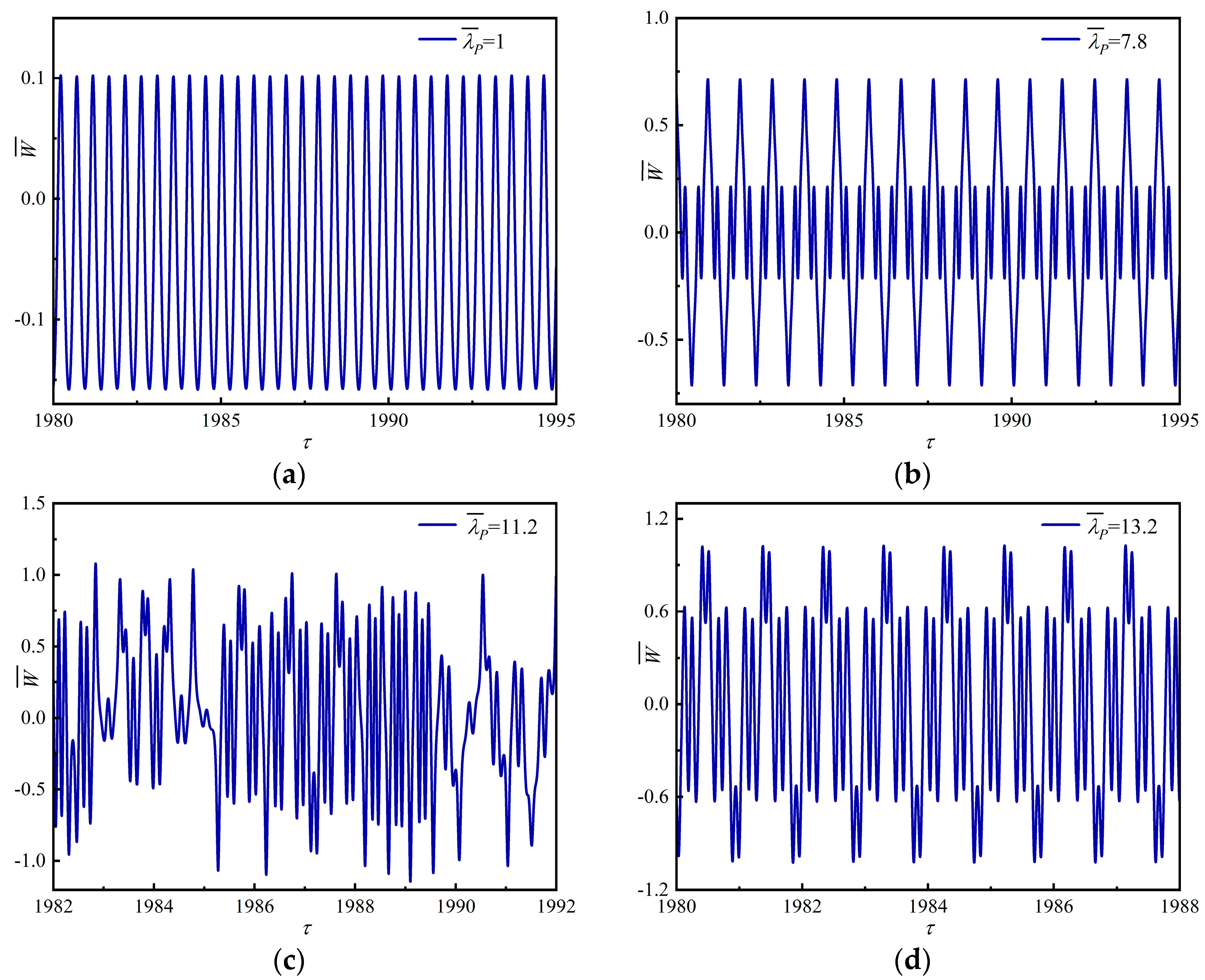

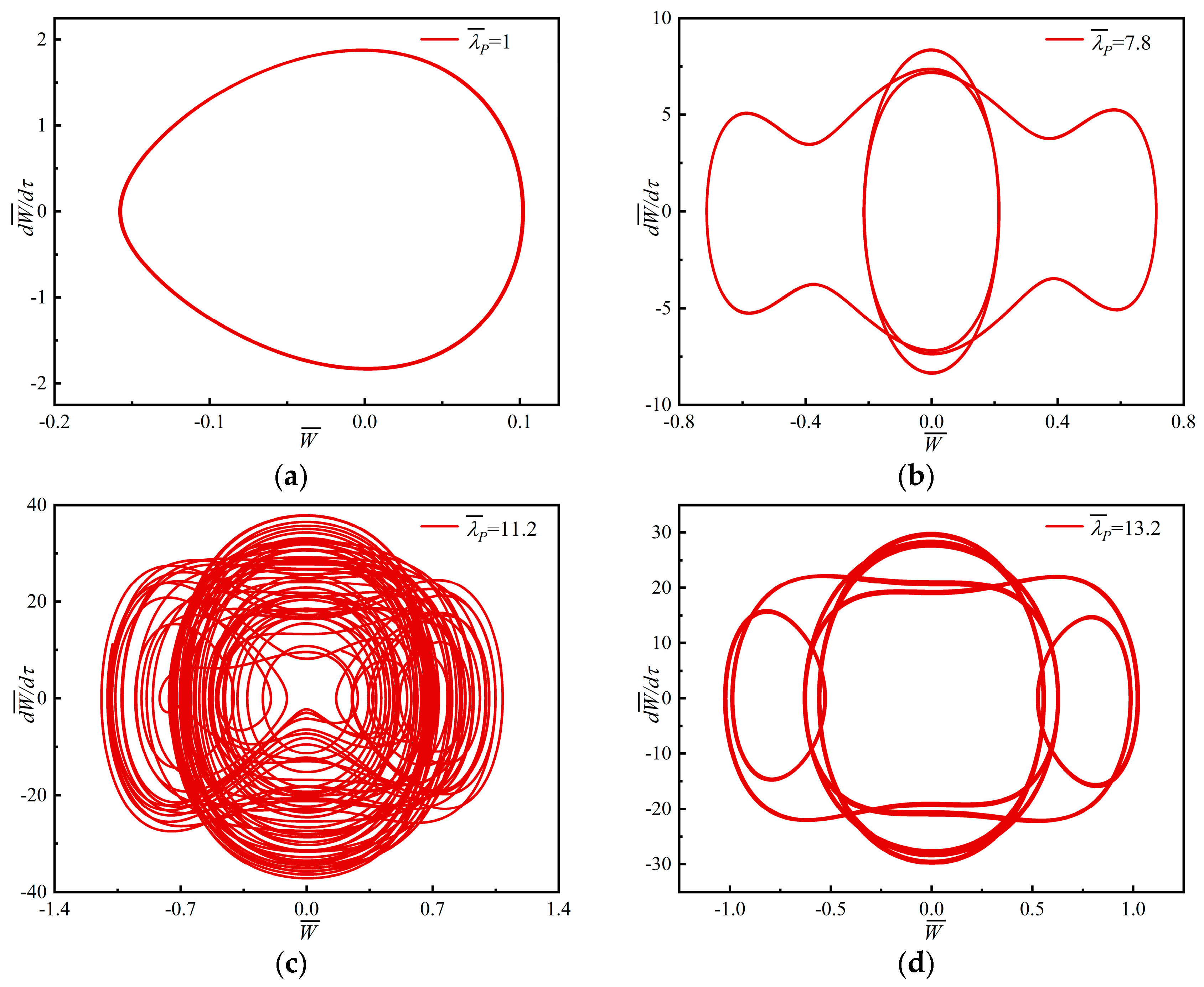

4.3. Bifurcation and Chaotic

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

Appendix B

Appendix C

References

- Gui, Y.F.; Wu, R.J. Buckling analysis of embedded thermo-magneto-electro-elastic nano cylindrical shell subjected to axial load with nonlocal strain gradient theory. Mech. Res. Commun. 2023, 128, 104043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ni, Y.W.; Sun, J.B.; Zhang, J.L.; Tong, Z.Z.; Zhou, Z.H.; Xu, X.S. Accurate buckling analysis of magneto-electro-elastic cylindrical shells subject to hygro-thermal environments. Appl. Math. Model. 2023, 128, 798–817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.F.; Gao, Y.S.; Wang, X.; Markert, B.; Zhang, S.Q. Finite element analysis of functionally graded magneto-electro-elastic porous cylindrical shells subjected to thermal loads. Mech. Adv. Mater. Struct. 2024, 31, 4003–4018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dat, N.D.; Anh, V.T.T.; Duc, N.D. Vibration characteristics and shape optimization of FG-GPLRC cylindrical shell with magneto-electro-elastic face sheets. Acta. Mech. 2023, 234, 4749–4773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellouz, H.; Jrad, H.; Wali, M.; Dammak, F. Large deflection analysis of FGM/magneto-electro-elastic smart shells with porosities under multi-physics loading. Mech. Adv. Mater. Struct. 2024, 31, 7299–7323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meuyou, H.H.; Ngak, F.P.E.; Ntamack, G.E.; Azrar, L. Semi-analytical three-dimensional solutions for static behavior of arbitrary functionally graded multilayered magneto-electro-elastic shells. Mech. Adv. Mater. Struct. 2024, 31, 7218–7243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellouz, H.; Jrad, H.; Wali, M.; Dammak, F. Numerical modeling of geometrically nonlinear responses of smart magneto-electro-elastic functionally graded double curved shallow shells based on improved FSDT. Comput. Math. Appl. 2023, 151, 271–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, B.C.; Zhao, R.; Yu, K.P. Nonlinear combined harmonic resonances of composite cylindrical shells operating in hygro-thermo-electro-magneto-mechanical fields. Compos. Struct. 2024, 331, 117877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gan, L.L.; She, G.L. Nonlinear transient response of magneto-electro-elastic cylindrical shells with initial geometric imperfection. Appl. Math. Model. 2024, 132, 166–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tu, P.H.; Ke, T.V.; Trai, V.K.; Hoai, L. An isogeometric analysis approach for dynamic response of doubly-curved magneto elec-tro elastic composite shallow shell subjected to blast loading. Def. Technol. 2024, 41, 159–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tornabene, F.; Viscoti, M.; Dimitri, R. Magneto-Electro-Elastic Analysis of Doubly-Curved Shells: Higher-Order Equivalent Layer-Wise Formulation. CMES-Comp. Model. Eng. 2025, 142, 1767–1838. [Google Scholar]

- Brischetto, S.; Cesare, D.; Mondino, T. An Exact 3D Shell Model for Free Vibration Analysis of Magneto-Electro-Elastic Composite Structures. J. Compos. Sci. 2025, 9, 399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Y.D.; Ma, B.B. Magnetoelastic combined resonance and stability analysis of a ferromagnetic circular plate in alternating magnetic field. Appl. Math. Mech. 2019, 40, 925–942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gan, L.L.; She, G.L. Nonlinear combined resonance of magneto-electro-elastic plates. Eur. J. A Solids 2025, 109, 105492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jahangiri, R.; Rezaee, M.; Manafi, H. Nonlinear and chaotic vibrations of FG double curved sandwich shallow shells resting on visco-elastic nonlinear Hetenyi foundation under combined resonances. Compos. Struct. 2022, 295, 115721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, H.X.; She, G.L. Nonlinear combined resonances of axially moving graphene platelets reinforced metal foams cylindrical shells under forced vibrations. Nonlinear Dyn. 2024, 112, 419–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aghamohammadi, M.; Sorokin, V.; Mace, B. Dynamic analysis of the response of Duffing-type oscillators subject to interacting parametric and external excitations. Nonlinear Dyn. 2021, 107, 99–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, J.; Yuan, X.; Jiao, J.; Zhang, H. Computation of axisymmetric nonlinear low-frequency resonances of hyperelastic thin-walled cylindrical shells. Appl. Math. Model. 2021, 94, 332–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, W.B.; Liu, J.; Zang, Q.S.; Lin, G. Magneto-electro-elastic semi-analytical models for free vibration and transient dynamic responses of composite cylindrical shell structures. Mech. Mater. 2020, 148, 103495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amabili, M.; Pellicano, F.; Païdoussis, M.P. Nonlinear vibrations of simply supported, circular cylindrical shells, coupled to quiescent fluid. J. Fluid. Struct. 1998, 12, 883–918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X. Parametric resonances of rotating composite laminated nonlinear cylindrical shells under periodic axial loads and hygrothermal environment. Compos. Struct. 2020, 255, 112887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Properties | Material Constants | CoFe2O4 | MEE | BaTiO3 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Elastic constant | c11 = c22 (GPa) | 286 | 213 | 166 |

| c12 | 173 | 113.5 | 77 | |

| c13 = c23 | 170 | 112.8 | 78 | |

| c33 | 269.5 | 206.5 | 162 | |

| c44= c55 | 45.3 | 49.7 | 43 | |

| C66 | 56.5 | 49.8 | 44.5 | |

| Piezoelectric constant | e31 = e32 (C/m2) | 0 | −2.71 | −4.4 |

| e33 | 0 | 8.86 | 18.6 | |

| e15 =e24 | 0 | 0.15 | 11.6 | |

| Dielectric constant | s11 = s22 (10−9 C2/Nm2) | 0.08 | 0.71 | 11.2 |

| s33 | 0.093 | 6.32 | 12.6 | |

| Magnetic constant | μ11 = μ22 (10−4 Ns2/C2) | −5.9 | −1.92 | 0.05 |

| μ33 | 1.57 | 0.83 | 0.1 | |

| Piezomagnetic constant | q31 = q32 (N/Am) | 580 | 222.6 | 0 |

| q33 | 699.7 | 292 | 0 | |

| q15 = q24 | 550 | 185.13 | 0 | |

| Magnetoelectric coupling constant | d11 = d22 (10−12 Ns/VC) | 0 | 5.35 | 0 |

| d33 | 0 | 2751.4 | 0 | |

| Thermal modulus | β1 (106 N/Km2) | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| β2 = β3 | 1.1 | 1.1 | 1.1 | |

| Density | ρ (kg/m3) | 5300 | 5500 | 5800 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

She, G.-L.; Gan, L.-L. Nonlinear Combined Resonance of Thermo-Magneto-Electro-Elastic Cylindrical Shells. Dynamics 2025, 5, 48. https://doi.org/10.3390/dynamics5040048

She G-L, Gan L-L. Nonlinear Combined Resonance of Thermo-Magneto-Electro-Elastic Cylindrical Shells. Dynamics. 2025; 5(4):48. https://doi.org/10.3390/dynamics5040048

Chicago/Turabian StyleShe, Gui-Lin, and Lei-Lei Gan. 2025. "Nonlinear Combined Resonance of Thermo-Magneto-Electro-Elastic Cylindrical Shells" Dynamics 5, no. 4: 48. https://doi.org/10.3390/dynamics5040048

APA StyleShe, G.-L., & Gan, L.-L. (2025). Nonlinear Combined Resonance of Thermo-Magneto-Electro-Elastic Cylindrical Shells. Dynamics, 5(4), 48. https://doi.org/10.3390/dynamics5040048