Abstract

This case report describes index pancreatoduodenectomy in a 32-year-old male following a close-range gunshot wound to the abdomen, with consequent 4 cm pancreatic head defect, duodenal and common bile duct perforation, right kidney laceration, and through-and-through inferior vena cava (IVC) injury. Although standard trauma protocols often favor damage control surgery (DCS) with delayed reconstruction in unstable patients, this patient’s hemodynamic stability—attributed to retroperitoneal self-tamponade—enabled a single-stage definitive approach. The rationale for immediate reconstruction was to prevent the risks associated with delayed management, such as ongoing pancreatic and biliary leakage, chemical peritonitis, and subsequent sepsis or hemorrhage. This case highlights that, in select stable patients with severe pancreaticoduodenal trauma, immediate pancreatoduodenectomy may be preferable to DCS, provided care is delivered in a high-volume hepatopancreaticobiliary (HPB) center with appropriate expertise and resources.

1. Introduction

Penetrating retroperitoneal trauma carries a significant risk of mortality, reported as between 11 and 25% [1,2,3,4]. While patients with intraperitoneal injuries typically present with hemodynamic instability due to ongoing hemorrhage within the distensible peritoneal cavity [5,6], venous hemorrhage within the minimally distensible retroperitoneum can produce a self-tamponading effect through the equalization of local venous and retroperitoneal pressures, thus achieving temporary hemodynamic control [7,8]. In the presented case, this stability offered the opportunity to consider definitive repair of a major pancreatic head injury through immediate pancreaticoduodenectomy as opposed to the standard practice of damage control surgery (DCS) and staged repair [9]. Therefore, this case, in conjunction with the existing literature, defines circumstances in which definitive repair can be considered. Further, a through-and-through injury to the inferior vena cava (IVC) presented a surgical challenge during initial exploration, given the need for prompt control of hemorrhage following release of the self-tamponaded retroperitoneal hematoma. Drawing on pre-existing techniques in endovascular occlusion of the aorta [10], we describe the successful use of intraluminal balloon occlusion to control hemorrhage of the IVC.

2. Case Summary

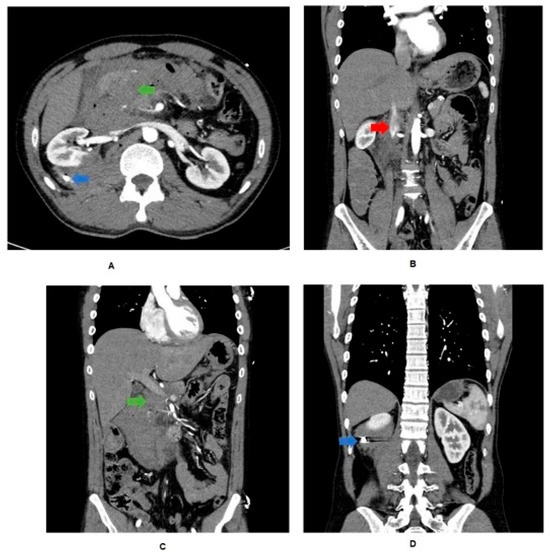

A 32-year-old man presented to an Australian level 1 trauma center following a gunshot wound to the abdomen from close range, with an entry wound left of midline and no exit wound. He was hemodynamically stable, with a subsequent multiphase computed tomography (CT) scan (Figure 1) demonstrating injury to the head of the pancreas with associated hematoma, perforation of the transverse colon, a right kidney laceration with hematoma, and the bullet within the right posterior pararenal space. The CT scan also suggested active bleeding from the inferior pancreaticoduodenal artery (IPDA), with likely injury to the common bile duct (CBD) and duodenum at the ampulla, representing an American Association for the Surgery of Trauma (AAST) grade V extrahepatic biliary tree injury. An emergency laparotomy was subsequently performed. At the time of anesthesia induction, the patient had a supported blood pressure of 130/60 mmHg and a heart rate of 110, with a base excess of −3.3. As part of a massive transfusion protocol, a total of 4 units of packed red cells were administered during pre-operative resuscitation.

Figure 1.

CT trauma findings. (A) Bullet (blue arrow) evident in retrorenal space with associated hematoma. Blush and hematoma evident from IPDA. Free air from duodenal perforation. Aorta intact. (B) Loss of IVC wall continuity (red arrow). (C) Portal vein spared, but CBD and duodenum perforated (green arrow). (D) Bullet evident in retrorenal space with associated hematoma.

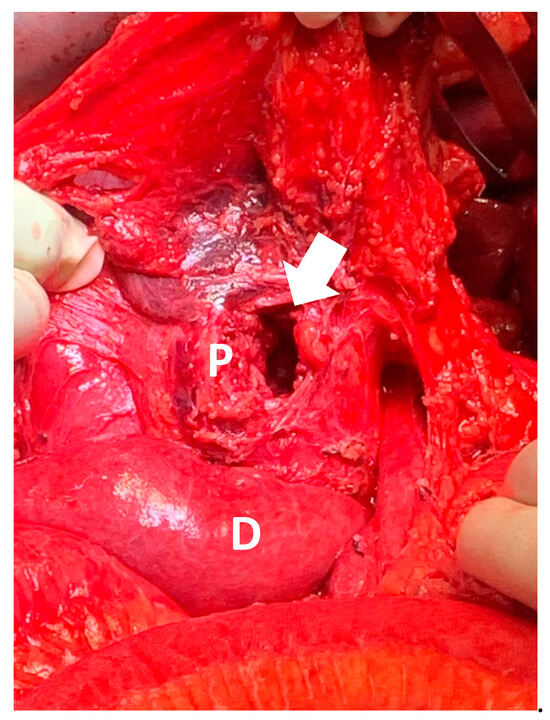

During the procedure, a non-expanding retroperitoneal hematoma was identified, indicating a venous source of hemorrhage with retroperitoneal self-tamponade. Access to the hematoma revealed anterior and posterior defects in the infrarenal IVC (AAST grade III abdominal vascular injury). Hemostasis of the IVC was achieved by proximal balloon catheter occlusion, with venorrhaphy of the posterior and anterior IVC defects using 6-0 prolene (Figure 2). The total IVC occlusion time was approximately 6 min. A right nephrectomy was performed to control hemorrhage, along with an extended right hemicolectomy. The bullet was retrieved during the procedure and sent with the operative specimens for histopathology and subsequent forensic pathology. Intra-operatively, the decision was made to perform a pancreaticoduodenectomy due to a 4 cm defect in the head of the pancreas and associated duodenal perforation (Figure 3 and Figure 4), representing an AAST grade V pancreatic injury. During the procedure, the patient had an estimated blood loss of 800 mL, requiring a further unit of packed red cells and one unit of cryoprecipitate. Cell salvage was not used.

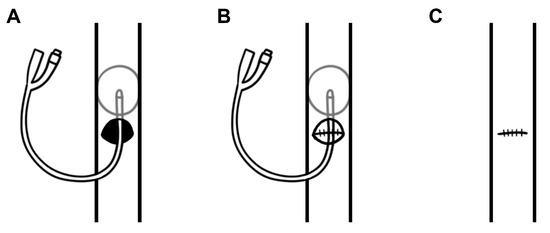

Figure 2.

A diagrammatic representation of intraluminal balloon occlusion of a through-and-through inferior vena cava (IVC) injury by (A) placement of a 14 Fr Foley catheter proximally through the defect, (B) repair of the posterior wall defect using 6-0 prolene, and (C) repair of the anterior wall defect using 6-0 prolene and subsequent catheter removal.

Figure 3.

Intra-operative photograph of head of pancreas (P) and duodenum (D), with arrow indicating a 4 cm defect in head of pancreas.

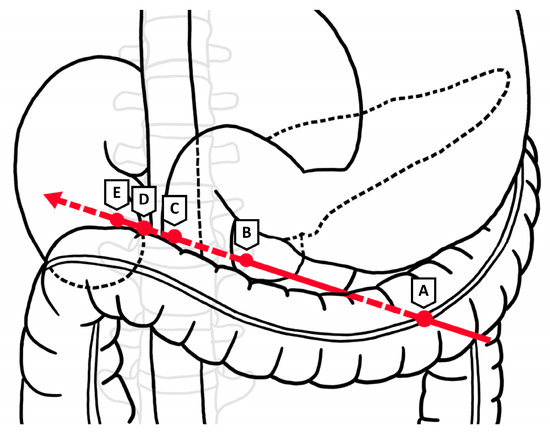

Figure 4.

Projectile trajectory through (A) distal transverse colon, (B) pancreas and duodenum at ampulla, (C) IVC, (D) lumbar vertebra, and (E) inferior pole of right kidney. Arrow indicates direction of travel of projectile.

Two surgical drains were placed during the procedure, sited on the right side posterior to the hepaticojejunostomy within the right retroperitoneum, and on the left side posterior to the gastrojejunostomy and anterior to the pancreaticojejunostomy and hepaticojejunostomy. Drain amylase levels peaked at 1891 and 22,792 units/liter on day 3 post-operation, resolving to 90 and 757 units/liter by day 7 post-operation, upon which both drains were removed. On serial CT imaging, there was evidence of post-operative pancreatitis without the development of a pancreatic fistula or ongoing bile leak, which was managed supportively (Clavien Dindo I). The patient was commenced on prophylactic heparin 5000 units twice daily on day 0 post-procedure, which was transitioned to prophylactic enoxaparin 40 mg once daily. He received total parenteral nutrition for 18 days post-operation, with gradual reintroduction of oral diet in addition to pancreatic enzyme supplementation following this. In a contrast meal follow-through CT study during this period, the patient had no evidence of stricture or obstruction in the gastrojejunal anastomosis, and had no significant delay in gastric emptying. The operative wound healed well, without evidence of a surgical site infection.

The patient’s post-operative stay was complicated by a non-occlusive infrarenal IVC thrombus and superior mesenteric vein (SMV) thrombus, which were managed with therapeutic enoxaparin (Clavien Dindo II). After an otherwise uneventful recovery, the patient was discharged from the hospital at 19 days post-procedure and remained well at follow-up after three months. He returned to his baseline independent level of function and continued to tolerate a normal diet with pancreatic enzyme supplementation. Repeat imaging showed resolution of the IVC and SMV thrombi with no venous stenosis, and therapeutic anticoagulation was subsequently ceased. He remains alive and well four years post-operation.

3. Discussion

Typically, traumatic injuries involving hemorrhage are initially managed with damage control surgery (DCS), which encompasses an abbreviated laparotomy limited to critically unstable patients who have suffered penetrating injuries to multiple viscera and exsanguinating vascular injury, with the ultimate goals being prompt control of hemorrhage and gross contamination [11]. DCS procedures for these patients are typically performed in the shortest time possible to prevent the self-perpetuating physiological derangements of hypothermia, coagulopathy, and metabolic acidosis [12]. Hence, definitive repair of other structures is delayed until the patient is clinically stable after initial damage control [13]. In this case, patient stability was achieved by the removal and anastomosis of the perforated bowel, a nephrectomy, and repair of the IVC.

However, pancreaticoduodenal trauma presents a more complex clinical scenario, where a delay in definitive management may leave the patient vulnerable to the complex physiological changes experienced in the hours following severe trauma. Specifically, delayed definitive repair could result in the continued leakage of enzyme-rich pancreatic fluid into the peritoneal cavity and subsequent chemical peritonitis, which has the potential to cause visceral and vascular injury through proteolytic and lipolytic tissue degradation [14]. This is further compounded by the disruption of the integrity of endothelial and mucosal tight junctions, which is known to occur as part of the pro-inflammatory state induced by severe traumatic injury [15]. In theory, this continued insult to luminal structures within the peritoneal cavity may progress to hemorrhage or abdominal sepsis [14]. Therefore, the risks of delaying definitive management, as preferred in DCS, must be weighed against the fitness of the patient to undergo a more extensive surgical repair. In pancreatic trauma of AAST grade IV and above, whereby there is gross disruption of the pancreatic head, bile duct, and duodenum, pancreaticoduodenectomy is unavoidable [16]. However, there is a paucity of investigation into the procedure in the trauma setting owing to the rarity of injury and a well-reported reluctance to perform such a complex and time-consuming procedure in patients who are predominantly unstable at presentation. Most of these patients undergo a two-step or delayed pancreaticoduodenectomy once hemostasis and patient stability are ensured in a bid to avoid anastomotic breakdown and minimize DCS duration [17].

Large database studies have sought to compare patients with high-grade pancreatic injuries who did and did not undergo a trauma pancreaticoduodenectomy at index surgery. A propensity-matched analysis of patients with grade III/IV pancreaticoduodenal injuries using data from the Trauma Quality Improvement Program demonstrated comparable mortality between those who did and did not undergo trauma pancreaticoduodenectomy at index surgery (20.0% vs. 28.7%) [1]. However, those who underwent immediate pancreaticoduodenectomy had a 3-fold increase in the risk of major complications, largely owing to an increase in the rate of deep vein thrombosis, and had a longer median length of hospital stay. A similar analysis of patients with grade IV/V pancreaticoduodenal injuries using data from the National Trauma Data Bank also demonstrated no difference in mortality (33% vs. 37%) between patients who did or did not undergo an immediate pancreaticoduodenectomy and showed no difference in complications or the length of stay [18]. It should be noted that in both large database studies, patients who did not undergo pancreaticoduodenectomy received a heterogeneous range of conservative procedures, including partial pancreatectomy, simple repair, and drainage, and both studies excluded patients who underwent a delayed pancreaticoduodenectomy. While pancreaticoduodenectomy could feasibly be avoided in patients without proximal ductal disruption or non-reconstructable injuries, these studies do not aid in the decision-making for patients in whom pancreaticoduodenectomy is deemed unavoidable.

A recent systematic review and meta-analysis published in 2020 focused exclusively on patients who underwent a trauma pancreaticoduodenectomy, comparing a single-stage to a two-stage approach in 149 patients with grade IV and V injuries since 1983 [19]. All patients in this analysis who underwent a two-stage procedure were hemodynamically unstable. The majority of studies concluded that a delayed reconstructive approach should be favored in this unstable cohort, and that a single-stage procedure should be restricted only to stable patients. Despite this, patients with hemodynamic instability who underwent a single-stage procedure (mortality 34.2%) demonstrated a trend towards reduced mortality compared to those undergoing a two-stage procedure (mortality 38.7%). In comparison, stable patients undergoing a single-stage procedure demonstrated a mortality rate of only 14.6%. Although they noted that post-operative complications were common following trauma pancreaticoduodenectomy, a comparison of the complication rate between single- and two-stage procedures was not performed.

A subsequent single-center study conducted over a 14-year period in 2024 included 13 patients who underwent a trauma pancreaticoduodenectomy, approximately half of whom underwent a single-stage procedure [20]. Despite having comparable injury severity as measured by the injury severity score (ISS), patients who underwent pancreaticoduodenectomy at index surgery experienced reduced hospital length of stay (35.7 days vs. 41.3 days), reduced number of complications (1 vs. 1.7), and reduced mortality (0 patients vs. 2 patients) compared to those who underwent a staged procedure. This may reflect the appropriate selection of patients for immediate reconstruction, given that those who underwent a single-stage procedure had, overall, a higher mean blood pressure, lower mean heart rate, and smaller base deficit.

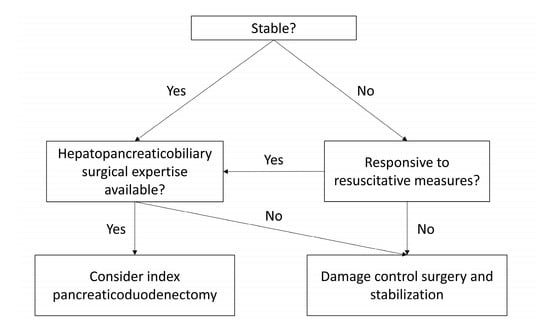

Based on these studies and experience at our center, we suggest a decision-making pathway for high-grade pancreaticoduodenal injury (Figure 5). Patients without significant physiological derangements with major proximal ductal disruption (AAST grade IV/V) should be considered for index pancreaticoduodenectomy. Patients requiring pancreaticoduodenectomy who are unable to tolerate a lengthy procedure due to profound hemodynamic instability or acidosis that is unresponsive to resuscitative efforts should be considered for DCS with a delayed reconstructive approach. As part of this decision-making process, it must be acknowledged that the outcome of this complex surgical repair is heavily determined by the peri-operative expertise of the surgical team in the management of pancreatic injury. As recommended by Krige et al. [21], trauma pancreaticoduodenectomy should only be undertaken by an experienced hepatopancreaticobiliary (HPB) surgeon. Penetrating firearm injury is an exceptionally rare occurrence in Australia [22], meaning patients with high-grade injury to the pancreas must be promptly transported to and treated in an HPB center well-equipped for the peri-operative management of these patients. A conservative approach may therefore be opted for in cases where such surgical expertise and skilled post-surgical care are not readily available, such as in combat settings.

Figure 5.

Decision-making algorithm for patients with AAST grade IV/V pancreatic injuries.

The feasibility of index pancreaticoduodenectomy in the described case was aided by prompt control of hemorrhage from the IVC injury. While current research surrounding REBOVC investigates percutaneous femoral access for catheter-led balloon occlusion of the IVC in animal models [23] and in human case reports [24], the technique described in this case utilizes the IVC lesion as a port of entry for the Foley catheter to achieve intraluminal balloon occlusion (Figure 4). This technique facilitated a brief ischemia time of only 6 min and is supported by previous case reports in achieving minimal dissection, improved exposure, and reduced operating time [25,26,27,28]. Data from the American Association for the Surgery of Trauma PROspective Observational Vascular Injury Treatment (PROOVIT) registry suggests that endovascular control of vena caval hemorrhage is utilized in as few as 2% of traumatic IVC injuries [29]; however, its successful application in these case series and the present case suggests its value as an adjunct in achieving hemodynamic stability in the setting of major vascular injury.

4. Conclusions

This case has illustrated that the clinical status of the patient must be taken into account when considering the surgical approach to repair pancreaticoduodenal trauma. Although instances of traumatic multi-organ injury to retroperitoneal structures are relatively rare, this case may serve as an example for intra-operative decision-making under similar circumstances in other tertiary HPB centers.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.S. and A.M.; methodology, K.K.; validation, K.K., formal analysis, K.K., J.S. and A.M.; data curation, K.K., J.F. and W.A.M.; writing—original draft preparation, J.F. and W.A.M.; writing—review and editing, K.K., J.S. and A.M.; supervision, J.S. and A.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

In accordance with our local Human Research Ethics Committee policy and the Declaration of Helsinki, case reports that involve less than five patients do not require ethics approval provided that written informed consent was obtained from the patient.

Informed Consent Statement

Written informed consent for publication of the case and intra-operative images was obtained from the patient.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Grigorian, A.; Dosch, A.R.; Delaplain, P.T.; Imagawa, D.; Jutric, Z.; Wolf, R.F.; Margulies, D.; Nahmias, J. The modern trauma pancreaticoduodenectomy for penetrating trauma: A propensity-matched analysis. Updates Surg. 2021, 73, 711–718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Phillips, B.; Turco, L.; Walters, R.W.; McDonald, D.; Wagner, M.; Cornell, D.; Bertelotti, R.; Agrawal, D.K.; Fitzgibbons, R., Jr.; Asensio, J.A. The Tiger Country Series: Penetrating Pancreaticoduodenal Injuries, Analysis of 145 Patients from the National Trauma Data Bank (NTDB) 2010 to 2014. J. Am. Coll. Surg. 2017, 225 (Suppl. S2), e189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Ragulin-Coyne, E.; Witkowski, E.R.; Chau, Z.; Wemple, D.; Ng, S.C.; Santry, H.P.; Shah, S.A.; Tseng, J.F. National trends in pancreaticoduodenal trauma: Interventions and outcomes. HPB 2014, 16, 275–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thompson, C.M.; Shalhub, S.; DeBoard, Z.M.; Maier, R.V. Revisiting the pancreaticoduodenectomy for trauma: A single institution’s experience. J. Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2013, 75, 225–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feliciano, D.V. Abdominal Trauma Revisited. Am. Surg. 2017, 83, 1193–1202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brown, C.V.; Velmahos, G.C.; Neville, A.L.; Rhee, P.; Salim, A.; Sangthong, B.; Demetriades, D. Hemodynamically “Stable” Patients with Peritonitis After Penetrating Abdominal Trauma: Identifying Those Who Are Bleeding. Arch. Surg. 2005, 140, 767–772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geeraerts, T.; Chhor, V.; Cheisson, G.; Martin, L.; Bessoud, B.; Ozanne, A.; Duranteau, J. Clinical review: Initial management of blunt pelvic trauma patients with haemodynamic instability. Crit. Care 2007, 11, 204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Turpin, I.; State, D.; Schwartz, A. Injuries to the inferior vena cava and their management. Am. J. Surg. 1977, 134, 25–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ho, V.P.; Patel, N.J.; Bokhari, F.; Madbak, F.G.; Hambley, J.E.; Yon, J.R.; Robinson, B.R.; Nagy, K.; Armen, S.B.; Kingsley, S.; et al. Management of adult pancreatic injuries: A practice management guideline from the Eastern Association for the Surgery of Trauma. J. Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2017, 82, 185–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DuBose, J.J.; Scalea, T.M.; Brenner, M.; Skiada, D.; Inaba, K.; Cannon, J.; Moore, L.; Holcomb, J.; Turay, D.; Arbabi, C.N.; et al. The AAST prospective Aortic Occlusion for Resuscitation in Trauma and Acute Care Surgery (AORTA) registry: Data on contemporary utilization and outcomes of aortic occlusion and resuscitative balloon occlusion of the aorta (REBOA). J. Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2016, 81, 409–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowley, D.M.G.; Barker, P.; Boffard, K.D. Damage Control Surgery—Concepts and Practice. J. R. Army Med. Corps. 2000, 146, 176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Malgras, B.; Prunet, B.; Lesaffre, X.; Boddaert, G.; Travers, S.; Cungi, P.J.; Hornez, E.; Barbier, O.; Lefort, H.; Beaume, S.; et al. Damage control: Concept and implementation. J. Visc. Surg. 2017, 154 (Suppl. S1), S19–S29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roberts, D.J.; Bobrovitz, N.; Zygun, D.A.; Kirkpatrick, A.W.; Ball, C.G.; Faris, P.D.; Stelfox, H.T.; Fabian, K.I.A.K.; Leppäniemi, E.E.; Indications for Trauma Damage Control Surgery International Study Group Karim Brohi Scott D’Amours Timothy C; et al. Evidence for use of damage control surgery and damage control interventions in civilian trauma patients: A systematic review. World J. Emerg. Surg. 2021, 16, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Walker, A.E. The Adult Pancreas in Trauma and Disease. Acad. Forensic Pathol. 2018, 8, 192–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmid-Schönbein, G.W. Inflammation and the autodigestion hypothesis. Microcirculation 2009, 16, 289–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Degiannis, E.; Glapa, M.; Loukogeorgakis, S.P.; Smith, M.D. Management of pancreatic trauma. Injury 2008, 39, 21–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seamon, M.J.; Kim, P.K.; Stawicki, S.P.; Dabrowski, G.P.; Goldberg, A.J.; Reilly, P.M.; Schwab, C.W. Pancreatic injury in damage control laparotomies: Is pancreatic resection safe during the initial laparotomy? Multicenter Study. Injury 2009, 40, 61–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van der Wilden, G.M.; Yeh, D.D.; Hwabejire, J.O.; Klein, E.N.; Fagenholz, P.J.; King, D.R.; de Moya, M.A.; Chang, Y.; Velmahos, G.C. Trauma Whipple: Do or Don’t After Severe Pancreaticoduodenal Injuries? An Analysis of the National Trauma Data Bank (NTDB). World J. Surg. 2014, 38, 335–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Carvalho, M.E.A.J.; Cunha, A.G. Pancreaticoduodenectomy in trauma: One or two stages? Injury 2020, 51, 592–596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noorbakhsh, S.; Wagner, V.; Arientyl, V.; Orlin, S.; Koganti, D.; Fransman, R.B.; Bishop, E.S.; Castater, C.A.; Nguyen, J.; Castro, A.D.; et al. Pancreaticoduodenectomy in high-grade pancreatic and duodenal trauma. Injury 2024, 55, 111721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krige, J.E.; Beningfield, S.J.; Nicol, A.J.; Navsaria, P. The management of complex pancreatic injuries. S. Afr. J. Surg. 2005, 43, 92–102. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Cameron, P.A.; Fitzgerald, M.C.; Curtis, K.; McKie, E.; Gabbe, B.; Earnest, A.; Christey, G.; Clarke, C.; Crozier, J.; Dinh, M.; et al. Overview of major traumatic injury in Australia—Implications for trauma system design. Injury 2020, 51, 114–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reynolds, C.L.; Celio, A.C.; Bridges, L.C.; Mosquera, C.; O’Connell, B.; Bard, M.R.; DeLa’o, C.M.; Toschlog, E.A. REBOA for the IVC? Resuscitative balloon occlusion of the inferior vena cava (REBOVC) to abate massive hemorrhage in retrohepatic vena cava injuries. J. Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2017, 83, 1041–1046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ribeiro, M.A., Jr.; Belardim, C.M.; Pastori, R.D.; Pinho, A.J.; Custódio, C.G.; Niero, H.B.; Rodrigues, J.M.; Ordoñez, C. Evaluating the use of Resuscitative Endovascular Balloon Occlusion of the Vena Cava (REBOVC) in Retrohepatic Vena Cava Injuries: Indications Technical Aspects and Outcomes. Panam J. Trauma Crit. Care Emerg. Surg. 2022, 11, 9–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mochida, Y.; Sekiguchi, K.; Nishimura, H.; Kaita, Y.; Yamaguchi, Y.; Yamaguchi, Y.M. A Novel Technique of Hemorrhage Control for an Inferior Vena Cava Injury From an Abdominal Stab Wound Using Two Balloon Occlusion Catheters: A Case Report. Cureus 2025, 17, e81009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howell, E.C.; Kulkarni, S.S.; Walker, P.F.; Morrison, J.J.; Kundi, R.; Scalea, T.M. Endovascular Balloon Occlusion of the Inferior Vena Cava in Trauma: A Single-Center Case Series. J. Am. Coll. Surg. 2023, 236, e1–e7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bisulli, M.; Gamberini, E.; Coccolini, F.; Scognamiglio, G.; Agnoletti, V. Resuscitative endovascular balloon occlusion of vena cava: An option in managing traumatic vena cava injuries. Case Reports. J. Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2018, 84, 211–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ravikumar, S.; Stahl, W.M. Intraluminal Balloon Catheter Occlusion for Major Vena Cava Injuries. J. Trauma 1985, 25, 458–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stonko, D.P.; Azar, F.K.; Betzold, R.D.; Morrison, J.J.; Fransman, R.B.; Holcomb, J.; Bee, T.; Fabian, T.C.; Skarupa, D.J.; Stein, D.M.; et al. Contemporary Management and Outcomes of Injuries to the Inferior Vena Cava: A Prospective Multicenter Trial From PROspective Observational Vascular Injury Treatment. Am. Surg. 2021, 89, 714–719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).