Abstract

Background/Objectives: Hurricane exposure is a growing public health concern that frequently results in posttraumatic stress symptoms (PTSS) in families. Research suggests that contextual factors, including whether or not individuals evacuate, evacuation stress, perceived sense of control, and peritraumatic distress, contribute to PTSS development. Yet, no known research has evaluated how these variables relate to one another, limiting understanding of how and why evacuation-related circumstances impact PTSS. This study investigated how evacuation experiences and PTSS differ between hurricane evacuees and non-evacuees. Methods: Parents (N = 211) reported on their evacuation experiences and perceptions, as well as their and their child’s PTSS, following Hurricane Ian. Results: Evacuated participants reported greater evacuation stress and greater PTSS in themselves and their child relative to non-evacuated participants. Parents’ sense of control was negatively associated with parent evacuation stress and parent peritraumatic distress in the non-evacuated group only. There were no direct associations between parents’ sense of control and parent or child PTSS in either group. In the non-evacuated group, parent evacuation stress was indirectly related to parent PTSS via parents’ sense of control and parent peritraumatic distress. Similarly, parent evacuation stress was indirectly related to child PTSS via each of the aforementioned variables and parent PTSS in the non-evacuated group only. Conclusions: Stress associated with hurricane evacuation may impact parent’s perceived sense of control, which may contribute to greater parent peritraumatic stress, resulting in greater PTSS among parents and children within families that did not evacuate prior to a hurricane. Findings highlight mechanisms that may inform treatment interventions and public health policy.

1. Introduction

Natural disasters directly impact 200 million people each year, among the most frequent and lethal of which are hurricanes and other storms [1]. Concerningly, intense and destructive hurricanes are increasingly common [2,3]. Growing coastal populations, social and infrastructural vulnerabilities, and the effects of climate change are expected to result in an even greater number of individuals being impacted by severe hurricanes in the near future [1,4]. As such, hurricane exposure is a growing public health concern.

Post-traumatic stress symptoms (PTSS) are among the most common psychological consequences of hurricanes and other natural disasters [5,6,7]. Parents and youth are particularly vulnerable to the development of such problems following disaster exposure [5,8,9]. Yet, most epidemiological studies of PTSS following disaster exposure indicate that fewer than 30% of adults and youth experience chronic and severe symptoms [5]. Consideration of contextual factors may help clarify how, and for whom, PTSS develop post-disaster.

One contextual factor that may influence how parents and children experience a hurricane is whether or not they evacuated their home. Evacuated parents are less likely to be injured than non-evacuees and report feeling safer during the storm relative to non-evacuated parents [9,10]. Yet, evacuation can be psychologically taxing despite reduced risk of physical harm. Relative to non-evacuated families, evacuated families report higher levels of overall stress, more family disagreements, and greater stress related to transportation logistics before and during the hurricane [10]. Evacuation-related stress is associated with PTSS in mothers and children three months post-disaster, even after controlling for actual hurricane exposure [11]. Thus, parents and children may be at risk of developing PTSS following a hurricane regardless of evacuation status, but the mechanisms by which symptoms develop may vary due to varying contextual environments.

For example, stress associated with resource limitations or other obligations may prevent families who otherwise would have evacuated from leaving their homes. Extant research has identified frequently endorsed barriers to evacuation, including poor health or disability [12,13], lack of transportation [14], having pets [14,15], and needing to stay to protect one’s home or business [13,14,16]. In a sample of mothers, factors such as having more children at home, owning dogs, and needing to remain near home due to work commitments were each associated with reduced likelihood of hurricane evacuation [17]. Moreover, nearly 70% of those who did not evacuate reported that not having a place to evacuate to was influential in their decision to stay, whereas nearly 90% of evacuated mothers reported that having a place to go to influenced their decision. Logistical and financial evacuation challenges may limit access to shelters or other evacuation locations, and feeling obligated to remain at home to protect one’s property or being required to report to work may also result in families perceiving evacuation as unviable. As such, evacuation stressors may make evacuation difficult or even impossible for many families.

Parents who decide not to evacuate due to evacuation stressors may perceive limited control over their decision. Though no known research has examined the relevancy of hurricane evacuation factors to sense of control, a study of displaced earthquake survivors indicated that survivors who relocated out of the earthquake-prone region reported a greater sense of control 14 months post-disaster relative to those who remained within the region or relocated but later returned [18]. Though the reason for this association was not directly investigated, social and economic problems were by-and-large the most commonly reported reasons survivors remained within or returned to the earthquake-prone region. It may be that these factors limited opportunity for individuals who wanted to permanently relocate to do so, thereby contributing to a lower sense of control within these groups.

Some research suggests that sense of control among natural disaster survivors is relevant to PTSS development. In the aftermath of Hurricane Katrina, a low sense of personal control was positively related to acute stress disorder symptoms among survivors at an emergency shelter [19]. Additional extant research indicates that feeling a low sense of control is predictive of PTSS in adult and adolescent earthquake survivors [18,20,21], and high sense of control is associated with posttraumatic growth [22]. Such relations may be explained indirectly through peritraumatic distress.

Peritraumatic distress, defined as the emotional and physiological distress experienced during or immediately following a traumatic event [23], appears theoretically and empirically relevant to sense of control and PTSS. How an individual initially appraises a potentially traumatic event, including their ability to cope and respond to the event, is theorized to precipitate and influence peritraumatic distress [24]. For example, appraisals of threat may evoke fear and appraisals of being blocked from a goal (such as evacuating) may evoke anger [25]. Thus, if a person appraises an active hurricane as being a threat to their life that they have limited control over, they may consequently experience peritraumatic fear and anger responses that may precipitate PTSS development. Indeed, appraisals such as perceived threat to life are associated with PTSS among parent and youth hurricane survivors [26,27], and perceived life threat is associated with PTSS among children, even in the absence of actual life threat [28]. Moreover, a meta-analysis suggests that peritraumatic distress is positively associated with PTSS, even when several months or years have passed since the trauma occurred, though the strength of the associations tend to decline with time [29]. Such findings highlight the importance of subjective peritraumatic perceptions to the development of PTSS. However, no known studies have explicitly evaluated associations of sense of control, peritraumatic distress, and PTSS. Investigation into these relations may offer additional insight into prevention and treatment of PTSS among hurricane survivors.

Parent PTSS is also implicated in the development of PTSS in children [30]. If a parent is experiencing PTSS, children may adopt similar coping mechanisms or ways of interpreting and responding to stressful events, such as natural disasters. Indeed, the likelihood of children developing PTSS is often contingent upon the adaptive or maladaptive nature of parent responses to traumatic experiences [31,32]. Parents with PTSS may also experience impairments in parenting behavior that may result in increased internalizing and externalizing problems in their children [33,34,35]. As such, examining the effects of parent PTSS on child PTSS is relevant to understanding impacts of disasters on families.

2. Current Study

PTSS development is a common consequence of exposure to natural disasters such as hurricanes [5], yet many families do not evacuate, oftentimes due to stressful barriers that are out of their control. No known research has investigated if evacuation stress is associated with sense of control, yet research indicates that evacuated disaster survivors report greater senses of control relative to non-evacuated survivors [18], and sense of control is associated with PTSS in adults and youth [18,20,21]. Moreover, peritraumatic distress, a predictor of PTSS [29], may act as a mediator between sense of control and PTSS, given theory that peritraumatic distress is precipitated by how individuals appraise potentially traumatic events as they occur [24]. Such processes in parents may also lead to consequences in their children.

The purpose of the current study is to investigate how evacuated and non-evacuated hurricane survivors differ in relation to their evacuation experiences and PTSS. The study aims were as follows (1): to explore differences in evacuation stressors and PTSS by evacuation status; (2) to examine if associations between parents’ sense of control and parent evacuation stress, parent peritraumatic distress, and parent and child PTSS vary by evacuation status; (3) to investigate if parents’ sense of control and peritraumatic distress sequentially mediate the relation between parent evacuation stress and parent PTSS; and (4) to determine if these effects extend to child PTSS when parent PTSS is included as a mediator.

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Participants

Eligible participants (N = 211) were parents living in an area directly impacted by Hurricane Ian. Approximately half (49%) of the parents reported evacuating their homes for Hurricane Ian (n = 105). Of those who evacuated, 35.5% reported evacuating to a friend or relative’s home nearby (less than an hour away), 20.6% reported evacuating to a shelter nearby (less than an hour away), 36.4% reported evacuating to another place in Florida, and 7.5% reported leaving the state of Florida. See Table 1 for participant demographic information.

Table 1.

Parent demographics.

Parents also provided data on their child. If they had more than one child, parents were instructed to report on the child they believed was most impacted by the hurricane. Children were 44% female and between the ages of 7 and 18 (M age = 8.91, SD = 4.29). Children were 81.5% White, 8.1% Black, 0.9% Asian, 0.5% Middle Eastern/North African, 8.1% more than one race, 1.0% other, and 15.2% were Hispanic/Latino.

3.2. Measures

3.2.1. Evacuation Stress

Before and After the Storm Experiences (BASE) [10] is a self-report measure used to assess evacuation-related stressors. The current study utilized the 15 BASE items related to events that happened to people as they prepared to evacuate or stay home before the storm. Parents were asked to rate how stressful each event was on a 5-point scale. Item anchors were modified from the original scale to more clearly delineate whether or not an event occurred (0 = Event did not occur to 4 = Event occurred and was very stressful). Ratings were summed for a total score, with higher scores indicating greater evacuation stress. Research indicates scores on this measure are significantly related to parents’ perception of stress before and after the storm [10]. In the current sample, internal consistency was good (α = 0.89).

3.2.2. Sense of Control

A single item assessed sense of control over the decision to evacuate or not. Participants indicate how much control they feel they had over their family’s decision to evacuate using a 5-point scale (1 = No control at all to 5 = Complete control). Higher scores indicate greater sense of control over the decision to evacuate.

3.2.3. Peritraumatic Distress

The Peritraumatic Distress Inventory (PDI) [36] is a 13-item self-report measure used to assess the level of distress experienced during or immediately after a traumatic event. Items include common experiences occurring in response to an ongoing or recent traumatic experience. Parents rated their experiences using a 5-point scale (0 = Not at all true to 4 = Extremely true). Total score was calculated as the mean of all items. Higher scores indicate greater distress. The PDI has demonstrated good construct validity reliability [23,36]. The measure has also evidenced good internal consistency in a sample of disaster survivors (α = 0.82) [37]. In the current sample, the PDI demonstrated excellent internal consistency (α = 0.91).

3.2.4. Parent PTSS

The Posttraumatic Stress Checklist for DSM-5 (PCL-5) [38] is a gold-standard measure for evaluating symptoms of PTSD in adults. The measure includes 20-items that evaluate responses to a traumatic experience, and parents rated how much they were bothered by each problem in the past month on a 5-point scale (0 = Not at all to 4 = Extremely). Ratings were summed for a total score, with higher scores indicate greater posttraumatic stress symptoms. The PCL-5 has evidenced significant psychometric support [39], including excellent consistency in a sample of hurricane-exposed mothers (α = 0.95) [11]. In the current sample, the PCL-5 demonstrated excellent internal consistency (α = 0.97).

3.2.5. Child PTSS

The International Trauma Questionnaire Child and Adolescent Caregiver version (ITQ-CG) [40,41] is a parent/caregiver-report measure that evaluates symptoms of PTSD in youth. Parents report on 6 items that reflect common trauma reactions in youth and rate how much their child was bothered by each problem in the past month on a 5-point scale (0 = Never to 4 = Almost always). Ratings are summed for a total score that ranges from 0 to 24. The ITQ-CG has demonstrated good internal consistency in a sample of hurricane-exposed children and adolescents (α = 0.92) [27]. In the current sample, the ITQ-CG demonstrated excellent internal consistency (α = 0.90).

3.3. Procedure

All procedures were approved by the investigators’ local Institutional Review Board. Eligible participants (a) were parents with at least one child under age 18 and (b) residents of one of seven Florida counties directly impacted by Hurricane Ian (Charlotte, Collier, DeSoto, Hardee, Highlands, Lee, or Sarasota counties). Participants were recruited using three mechanisms: Research Match, social media advertising, and phone- and email-based outreach to community organizations located within eligible counties. Participants provided informed consent before completing an online survey battery. To verify eligibility and prevent fraudulent responses, several checks recommended in extant research were utilized and spread throughout the survey [42,43]. Checks included providing a zip code consistent with their reported county of residence, reporting a school or daycare name located within 50 miles of an eligible county, providing a child’s date of birth consistent with their reported age, choosing all five colors in a favorite color attention check item, and selecting “911” as the emergency telephone number they would dial in an emergency. Participants who passed four out of five of these checks and provided a valid mailing address (one response per household was permitted) located within an eligible county received a USD 5.00 gift card and a workbook on helping children cope after hurricanes. Data collection occurred between two and eight months post-disaster.

3.4. Analytic Strategy

All analyses were conducted in IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows (version 28, IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA). Distributions and outliers were examined within the full sample and within groups by evacuation status. No outliers were identified in the full sample or in the evacuation group. In the non-evacuation group, three univariate BASE outliers (i.e., +3.29 standard deviations from the mean) were identified and recoded to the next highest non-outlying value [44]. All distributions were approximately normal and data were homoscedastic. No multivariate outliers were observed.

Descriptive statistics and Pearson correlations were computed using standard procedures. Child PTSS was held constant when calculating correlations of parent PTSS and study variables (and vice versa). Independent samples t-tests (i.e., Student’s t-test) and chi-square tests were used to assess group equivalence. Fisher r-to-z transformations were utilized to determine if parents’ sense of control associations significantly differed between groups [45]. Analyses of indirect relations were evaluated using ordinary least squares logistic path analysis (PROCESS version 4.3; model 6) [46]. Two models were calculated. Parent evacuation stress was entered as the antecedent in both models. In Model 1, parent PTSS was entered as the consequent and parents’ sense of control and parent peritraumatic distress were entered as serial mediators. In Model 2, child PTSS was entered as the consequent and parents’ sense of control, parent peritraumatic distress, and parent PTSS were entered as serial mediators. The models were tested within the evacuation and non-evacuation groups. All path analyses were conducted using 10,000 bootstrap samples and coefficients that defined the models were evaluated using bootstrapped confidence intervals.

4. Results

4.1. Preliminary Analyses

Total sample descriptive statistics and correlations are presented in Table 2. Consistent with samples of hurricane survivors [47,48], parent PTSS scores were moderate in the current study. Child PTSS scores were relatively low and consistent with a sample of trauma-exposed youth [49]. Peritraumatic distress scores were high and greater than previously reported in samples of natural disaster survivors [50,51].

Table 2.

Total sample descriptive statistics and correlation coefficients.

4.2. Evacuation Stressors by Evacuation Status

Reported evacuation stressors are presented by evacuation status in Table 3. Chi-square tests were utilized to examine group equivalence. All stressors were more often reported by evacuated participants relative to non-evacuated participants, except for trouble getting gasoline and having disagreements with family about whether to evacuate or not, which were statistically equivalent across groups.

Table 3.

Evacuation stressors by evacuation status.

4.3. Mental Health and Stress by Evacuation Status

Descriptive statistics by evacuation status are presented in Table 4. Independent samples t-tests were employed to examine group equivalence. Participants who evacuated reported greater parent evacuation stress, parent PTSS, and child PTSS relative to participants who did not evacuate. There was no difference in parent peritraumatic distress or parents’ sense of control between groups.

Table 4.

Means and standard deviations of study variables by evacuation status.

4.4. Parents’ Sense of Control Associations by Evacuation Status

Associations between parents’ sense of control and mental health and stress variables were examined within evacuation status groups to determine if relations differed by evacuation status. Parents’ sense of control was significantly negatively associated with parent evacuation stress in the non-evacuated group, r(104) = −0.37, p < 0.001, but not the evacuated group, r(103) = −0.01, p = 0.94. The differences between these associations were significant, z = −2.71, p = 0.007. Moreover, parents’ sense of control was significantly negatively associated with parent peritraumatic distress in the non-evacuated group, r(104) = −0.50, p < 0.001, but not the evacuated group, r(103) = −0.08, p = 0.40. This difference was significant, z = −3.36, p < 0.001. When controlling for child PTSS, parents’ sense of control was not significantly associated with parent PTSS in the non-evacuated group, r(103) = −0.14, p = 0.14, or the evacuated group, r(102) = −0.10, p = 0.30. Similarly, parents’ sense of control was not associated with child PTSS in the non-evacuated group, r(103) = −0.10, p = 0.34, or the evacuated group, r(102) = −0.05, p = 0.60, when controlling for parent PTSS.

4.5. Factors Contributing to Parent PTSS

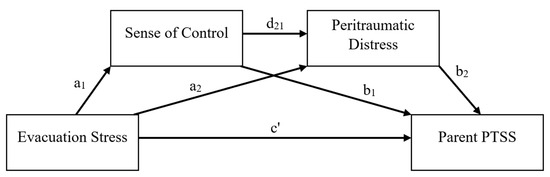

Model 1 was employed to determine the influence of parent evacuation stress on parent PTSS via parents’ sense of control and parent peritraumatic distress (see Figure 1 and Table 5). Parent evacuation stress was significantly inversely related to parents’ sense of control (a1 path) for the non-evacuated group, but not the evacuated group. Parents’ sense of control was not directly related to parent PTSS (b1 path) in any group, nor was parents’ sense of control a significant mediator of the parent evacuation stress-parent PTSS relation (a1b1 path). Yet, parents’ sense of control was significantly inversely related to parent peritraumatic distress (d21 path) for the non-evacuated group. This relation was not significant for the evacuated group. Moreover, the total indirect effect of parent evacuation stress on parent PTSS through parents’ sense of control and parent peritraumatic distress (a1d21b2 path) was significant for non-evacuated group only. In both groups, parent evacuation stress was significantly positively related to parent peritraumatic distress (a2 path), which was, in turn, significantly and positively related to parent PTSS (b2 path). Furthermore, the indirect effect of parent evacuation stress on parent PTSS through parent peritraumatic distress (a2b2 path) was significant across both groups, as was the direct effect of parent evacuation stress on parent PTSS (c′ path).

Figure 1.

Serial multiple mediation model predicting parent PTSS from parent evacuation stress. PTSS = Posttraumatic stress symptoms.

Table 5.

Serial multiple mediation effects of parent evacuation stress on parent PTSS.

4.6. Factors Contributing to Child PTSS

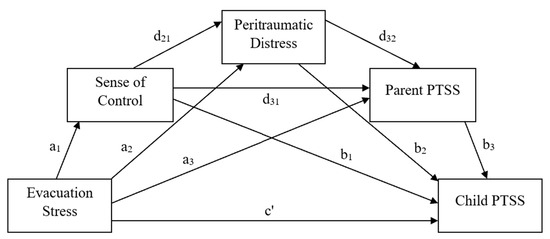

Model 2 expanded upon Model 1 to examine child PTSS as the outcome (see Figure 2 and Table 6). All effects that were significant (or insignificant) in Model 1 maintained significance (or insignificance) in their previously reported directions following the inclusion of child PTSS as the outcome in Model 2. Parents’ sense of control and parent peritraumatic distress were not directly related to child PTSS in either group (b1 and b2 paths, respectively), nor were parents’ sense of control or parent peritraumatic distress significant mediators of the parent evacuation stress-child PTSS relation (a1b1 and a2b2 paths, respectively). In both groups, parent PTSS was significantly positively related to child PTSS (b3 path) and a significant mediator of the relation of parent evacuation stress and child PTSS (a3b3 path). The indirect effects of parent evacuation stress on child PTSS through (a) parents’ sense of control and parent peritraumatic distress (a1d21b2 path) and (b) parents’ sense of control and parent PTSS (a1d31b3 path) were insignificant across groups. Yet, the indirect effect was significant through parent peritraumatic distress and parent PTSS (a2d32b3 path) in each group. Among the non-evacuated group only, the indirect effect of parent evacuation stress on child PTSS through parents’ sense of control, parent peritraumatic distress, and parent PTSS was significant (a1d21d32b3 path). The direct effect of parent evacuation stress on child PTSS was insignificant in both groups (c’ path).

Figure 2.

Serial multiple mediation model predicting child PTSS from parent evacuation stress.

Table 6.

Serial multiple mediation effects of parent evacuation stress on child PTSS.

5. Discussion

PTSS is among the most common psychological consequences of hurricanes and other natural disasters, especially among parents and youth [5]. Extant research indicates that evacuation stress and survivors’ sense of control are two contextual factors related to PTSS in disaster survivors [11,18]. This study expands upon prior research investigating associations between parent evacuation stress and PTSS in parents and their children by being the first to explore if parents’ sense of control and peritraumatic distress mediate these relations, and if those relations differ for families who evacuated versus did not evacuate.

5.1. Evacuee and Non-Evacuee Evacuation Experiences and PTSS

Parents who evacuated prior to Hurricane Ian reported experiencing more stressors relative to non-evacuated parents. All assessed evacuation stressors were more often reported by evacuated parents relative to non-evacuated parents, except for trouble getting gasoline and having disagreements with family about whether to evacuate or not, which were equivalent across groups. La Greca and colleagues [10] similarly reported that hurricane evacuees experienced more evacuation stressors relative to non-evacuees.

Regardless of evacuation status, greater evacuation stress was associated with greater parent and child PTSS, indicating that stress related to hurricane evacuation has broad mental health implications regardless of evacuation status. Yet, evacuation stress appears especially relevant to evacuees. Parents of evacuated families reported greater evacuation stress, parent PTSS, and child PTSS relative to non-evacuees. Results are consistent with extant research indicating that evacuation stress is greater among hurricane evacuees relative to non-evacuees [10] and is predictive of PTSS in mothers and youth post-hurricane [11]. Additional contextual factors may also contribute to greater PTSS among evacuated individuals. For example, individuals are more likely to evacuate if they live in vulnerable housing and areas heavily impacted by the storm [52]. Thus, hurricane evacuees may develop more PTSS relative to non-evacuees due to greater losses within their communities. Additionally, hurricane evacuees are more likely to be female [13,52] and a meta-analysis suggested that women are at greater risk for developing PTSD following disaster exposure relative to men [53]. Yazawa and colleagues [54] investigated reasons for this gender discrepancy and found that women are more effected by what happens to others during a traumatic event, even if they did not directly experience the trauma themselves. Additional research is needed to better understand how different contextual factors, such as evacuation, lead to the development of PTSS.

5.2. Evacuation Status and Parents’ Sense of Control

Evacuation status appears relevant to how individuals perceive traumatic events as they occur. Present results indicate that associations between parents’ sense of control and psychological functioning differ by evacuation status. Parents’ sense of control was negatively associated with parent evacuation stress and parent peritraumatic distress for non-evacuated parents only. In other words, parents who did not evacuate before the hurricane and perceived less control over their decision reported greater evacuation stress and peritraumatic distress. These relations were insignificant among evacuated parents and the differences between the correlation coefficients across groups were significant, suggesting that associations of parents’ sense of control and evacuation stress and peritraumatic distress are context dependent.

Results of the present study suggested that parents’ sense of control was not associated with parent or child PTSS in either group. This contrasts with prior research that indicated that low sense of control predicted greater PTSS in adult and adolescent earthquake survivors [18,20,21] and greater acute stress disorder symptoms in adult hurricane survivors housed in an emergency shelter [19]. Unlike those in prior research, approximately half of the present study participants evacuated prior to the disaster. Hurricane evacuees are injured less and report feeling safer than non-evacuees [9,10], perhaps due to reduced or absent direct exposure to the disaster as it unfolded. As PTSD prevalence is higher among those directly exposed to disasters at a greater intensity relative to those who were not directly exposed or were exposed at a lower intensity [55] differing degrees of disaster exposure between samples may account for differing relations of sense of control and PTSS across studies. Disaster type may further explain differences between the present results and prior research conducted with earthquake survivors. Unlike hurricanes, which are typically predicted to occur up to seven days in advance [56] earthquakes are unable to be reliably predicted [57]. Though evacuation stress is undoubtably experienced by many post-earthquake, sense of control perceived during an active earthquake is unlikely to be related to whether or not individuals chose to evacuate prior to the earthquake’s occurrence given lack of opportunity for advanced warning. Continued investigation into the contextual factors associated with disaster exposure is warranted to better understand mechanisms contributing to PTSS development.

5.3. Differential Effects of Parents’ Sense of Control on PTSS by Evacuation Status

Although parents’ sense of control and parent and child PTSS were not correlated, mediation analyses were suggestive of context-dependent indirect relations between these variables. In both groups, parent evacuation stress was positively associated with parent PTSS directly, as well as indirectly via parent peritraumatic distress. Thus, regardless of evacuation status, parents who experienced high evacuation-related stress also reported greater peritraumatic distress and PTSS. This finding builds upon well-established research linking peritraumatic distress and PTSS [29] by demonstrating that evacuation-related stress may predispose hurricane-exposed parents to higher levels peritraumatic distress and consequent PTSS. Parents’ sense of control was relevant to these relations among non-evacuated parents only. In the non-evacuated group, the relation of parent evacuation stress and parent PTSS was sequentially mediated by parents’ sense of control and parent peritraumatic distress. In other words, among parents who did not evacuate, high evacuation stress was associated with low sense of control, which in turn was associated with high peritraumatic distress, which was ultimately associated with high PTSS.

When child PTSS was evaluated as the outcome, parent PTSS appeared particularly relevant to both groups. With the exception of parent PTSS, no variables were directly associated with child PTSS in either group. In addition, indirect relations of parent evacuation stress and child PTSS were only significant when parent PTSS was included in the models. Thus, parent peritraumatic distress did not mediate the relation of parent evacuation stress and child PTSS without the inclusion of parent PTSS as a serial mediator. This may be due to the centrality of the parent’s perspective to all variables, as parent and child PTSS were reported by parents only, and child evacuation stress, child sense of control, and child peritraumatic distress were not measured. Though the link between parent and child PTSS is well-established, results may have differed if child-reported PTSS data were collected. In addition, little is known about associations of parent peritraumatic distress and child PTSS. Researchers of one known study evaluated the association of parent peritraumatic distress on child PTSS and found a positive relationship [58]. Child peritraumatic distress was also measured and found to be more elevated than parent peritraumatic distress on average, although it was unclear if child peritraumatic distress and later child PTSS were related. It may be that child peritraumatic distress is more relevant than parent peritraumatic distress to the present model. Additional research is needed to best understand parent and child peritraumatic distress and their contributions to child PTSS development.

Despite these differences, the effects of parents’ sense of control on child PTSS were otherwise consistent with those observed in the parent-only PTSS models. In the non-evacuated group, the association of parent evacuation stress and child PTSS was sequentially mediated by parents’ sense of control, parent peritraumatic distress, and parent PTSS. Parents’ sense of control was not related to any variables in the evacuated group. Thus, parents of non-evacuated families that experience high evacuation stress prior to a hurricane may appraise themselves as having less control over not evacuating their families, resulting in peritraumatic distress responses of greater intensity, increasing risk of PTSS development in themselves and their children. As these effects were not observed in evacuated participants, sense of control appears uniquely influential to adult and child PTSS in the context of non-evacuation, particularly when individuals are exposed to high degrees of evacuation-related stress.

5.4. Limitations

Despite the contributions of the current study, several limitations should be acknowledged. First, this study utilized a cross-sectional design, which limits the generalizability of the results and prevents the establishment of causality. Causal conclusions are further limited by the possibility of retrospective biases, which may have impacted participant’s ability to accurately report on past events and perceptions. For example, though participants were instructed to report on their perceived sense of control during the hurricane, their retrospective perceptions may have been biased by post-hurricane events and experiences. Future researchers may benefit from employing alternative methodologies to better understand relations between contextual factors and mental health variables. Additionally, this study specifically recruited from areas with the most severe hurricane exposure; it is unclear whether findings generalize to less severe hurricane experiences. Examination of additional factors, such as severity of trauma exposure and property damage [52], that may partially account for PTSS variance may be of benefit to future researchers. Additionally, the use of single informant data in the form of parent reports of child mental health symptoms limits the reliability and validity of the obtained child PTSS scores. Indeed, parent PTSS and parent reports of their child’s PTSS post-disaster are highly correlated [59] and parents’ own mental health symptoms may influence their report of their child’s symptoms. Therefore, future research should include both parent and child reports of child mental health symptoms to increase the reliability and validity of child symptoms. Furthermore, the sample demographics were predominately White, and while this reflects the demographics of the counties in which participants were recruited, it limits the generalizability of findings across racially and ethnically diverse populations. Additionally, participants largely identified as female and were parents of school-age children and adolescents. The generalizability of the results to non-female parents and parents of younger children may therefore be limited. Future studies should aim to recruit diverse samples to highlight the unique factors that impact disaster-related outcomes.

6. Conclusions

The present study investigated how hurricane evacuation experiences and PTSS differ in parents and youth by evacuation status. The results suggest that greater evacuation stress is associated with greater parent and child PTSS regardless of evacuation status, though parents in families that evacuate experience more evacuation stressors and greater overall evacuation stress than those in non-evacuated families. In addition, this study was the first to demonstrate that PTSS are greater among parents and children who evacuated relative to those who did not evacuate. This study was also the first to demonstrate that parent’s perceived sense of control over their evacuation decisions may be uniquely relevant to the development of PTSS in parent and youth within families that remained at home during a hurricane. Results highlight the importance of public health efforts to reduce stress-inducing barriers to hurricane evacuation, ensuring that those who want to evacuate feel in control over their ability to do so if they choose. In addition, adult and youth who did not evacuate before hurricane exposure and subsequently developed PTSS may benefit from exploring pre-evacuation experiences and control-related appraisals and beliefs with treatment providers, though additional research is necessary to fully understand these associations and efficacy of interventions. Continued research on the effects of contextual variables on the development of PTSS is necessary to optimize person-centered prevention and treatment efforts.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, R.C.B. and B.A.D.; Methodology, R.C.B. and J.L.T.; Formal Analysis, R.C.B.; Investigation, B.A.D., J.L.T. and R.C.B.; Writing—Original Draft Preparation, R.C.B. and J.L.T.; Writing—Review and Editing, B.A.D., R.C.B. and J.L.T.; Supervision, B.A.D. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and the protocol was approved by the Institutional Review Board of The University of South Dakota (IRB-22-282) on 28 November 2022.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent for participation was obtained from all study participants.

Data Availability Statement

Data supporting the findings of this study are available upon request from the corresponding author. The data were not publicly available due to privacy or ethical restrictions.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- CRED; UNDRR. Human Cost of Disasters: An Overview of the Last 20 Years 2000–2019. 2020. Available online: https://www.undrr.org/publication/human-cost-disasters-overview-last-20-years-2000-2019 (accessed on 30 November 2024).

- Grinsted, A.; Ditlevsen, P.; Christensen, J.H. Normalized U.S. hurricane damage estimates using area of total destruction, 1900–2018. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2019, 116, 23942–23946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Holland, G.; Bruyère, C.L. Recent intense hurricane response to global climate change. Clim. Dyn. 2014, 42, 617–627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bathi, J.R.; Das, H.S. Vulnerability of coastal communities from storm surge and flood disasters. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2016, 13, 239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bonanno, G.A.; Brewin, C.R.; Kaniasty, K.; La Greca, A.M. Weighing the costs of disaster: Consequences, risks, and resilience in individuals, families, and communities. Psychol. Sci. 2010, 11, 1–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Furr, J.M.; Comer, J.S.; Edmunds, J.M.; Kendall, P.C. Disasters and youth: A meta-analytic examination of posttraumatic stress. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 2010, 78, 765–780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldmann, E.; Galea, S. Mental health consequences of disasters. Annu. Rev. Public Health 2014, 35, 169–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Danzi, B.A.; Knowles, E.A.; Thomas, J.L. Childhood Posttraumatic Stress Disorder. In The Palgrave Encyclopedia of Disability; Palgrave Macmillan: Cham, Switzerland, 2024; pp. 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norris, F.H.; Sherrieb, K.; Galea, S. Prevalence and consequences of disaster-related illness and injury from Hurricane Ike. Rehabil. Psychol. 2010, 55, 221–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- La Greca, A.M.; Brodar, K.E.; Danzi, B.A.; Tarlow, N.; Silva, K.; Comer, J.S. Before the storm: Stressors associated with the Hurricane Irma evacuation process for families. Disaster Med. Public Health Prep. 2019, 13, 63–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- La Greca, A.M.; Tarlow, N.; Brodar, K.E.; Danzi, B.A.; Comer, J.S. The stress before the storm: Psychological correlates of hurricane-related evacuation stressors on mothers and children. Psychol. Trauma Theory Res. Pract. Policy 2022, 14, S13–S22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelly, J.T.; Danzi, B.A. Complex health needs in hurricane-affected youth and their families: Barriers, vulnerabilities, and mental health outcomes. Res. Child Adolesc. Psychopathol. 2025, 53, 905–919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, S.K.; McCarty, C. Fleeing the storm(s): An examination of evacuation behavior during Florida’s 2004 hurricane season. Demography 2009, 46, 127–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lazo, J.K.; Bostrom, A.; Morss, R.E.; Demuth, J.L.; Lazrus, H. Factors affecting hurricane evacuation intentions. Risk Anal. 2015, 35, 1837–1857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whitehead, J.C.; Edwards, B.; Van Willigen, M.; Maiolo, J.R.; Wilson, K.; Smith, K.T. Heading for higher ground: Factors affecting real and hypothetical hurricane evacuation behavior. Environ. Hazards 2000, 2, 133–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindell, M.K.; Lu, J.C.; Prater, C.S. Household decision making and evacuation in response to Hurricane Lili. Nat. Hazards Rev. 2005, 6, 171–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brodar, K.E.; La Greca, A.M.; Tarlow, N.; Comer, J.S. “My kids are my priority”: Mothers’ decisions to evacuate for Hurricane Irma and evacuation intentions for future hurricanes. J. Fam. Issues 2020, 41, 2251–2274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salcioglu, E.; Ozden, S.; Ari, F. The role of relocation patterns and psychosocial stressors in posttraumatic stress disorder and depression among earthquake survivors. J. Nerv. Ment. Dis. 2018, 206, 19–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mills, A.M.; Edmondson, D.; Park, C.L. Trauma and stress response among Hurricane Katrina evacuees. Am. J. Public Health 2007, 97, S116–S123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cankardaş, S.; Sofuoğlu, Z. Post-traumatic stress disorder symptoms and their predictors in earthquake or fire survivors. Turk. J. Psychiatry 2019, 30, 151–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Liu, H.; Jiang, X.; Wu, D.; Tian, Y. A longitudinal study of posttraumatic stress disorder symptoms and its relationship with coping skill and locus of control in adolescents after an earthquake in China. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e88263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ying, L.H.; Lin, C.-D.; Wu, X.-C.; Chen, C.; Greenberger, E.; An, Y.Y. Trauma severity and control beliefs as predictors of posttraumatic growth among adolescent survivors of the Wenchuan earthquake. Psychol. Trauma Theory Res. Pract. Policy 2014, 6, 192–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bunnell, B.E.; Davidson, T.M.; Ruggiero, K.J. The Peritraumatic Distress Inventory: Factor structure and predictive validity in traumatically injured patients admitted through a Level I trauma center. J. Anxiety Disord. 2018, 55, 8–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bovin, M.J.; Marx, B.P. The importance of the peritraumatic experience in defining traumatic stress. Psychol. Bull. 2011, 137, 47–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Power, M.; Dalgleish, T. Cognition and Emotion: From Order to Disorder, 3rd ed.; Psychology Press: New York, NY, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Danzi, B.A.; Knowles, E.A.; Kelly, J.T. Improving posttraumatic stress disorder assessment in young children: Comparing measures and identifying clinically-relevant symptoms in children ages six and under. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 19179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Danzi, B.A.; Knowles, E.A.; Bock, R.C. Posttraumatic stress disorder in disaster-exposed youth: Examining diagnostic concordance and model fit using ICD-11 and DSM-5 criteria. BMC Pediatr. 2025, 25, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Danzi, B.A.; Kelly, J.T.; Knowles, E.A.; Burdette, E.T.; La Greca, A.M. Perceived life threat in children during the COVID-19 pandemic: Associations with posttraumatic stress, anxiety, and depressive symptoms. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry Ment. Health 2024, 18, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, É.; Saumier, D.; Brunet, A. Peritraumatic distress and the course of posttraumatic stress disorder symptoms: A meta-analysis. Can. J. Psychiatry 2012, 57, 122–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silverstein, M.J.; Herress, J.; Ostrowski-Delahanty, S.; Stavropoulos, V.; Kassam-Adams, N.; Daly, B.P. Associations between parent posttraumatic stress symptoms (PTSS and later child PTSS: Results from an international data archive. Int. Soc. Trauma. Stress Stud. 2022, 35, 1620–1630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hiller, R.M.; Stedman, R.; Lobo, S.; Creswell, C.; Fearon, P.; Ehlers, A.; Murray, L.; Halligan, S. A longitudinal investigation of the role of parental responses in predicting children’s post-traumatic distress. J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry 2018, 59, 781–789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williamson, V.; Creswell, C.; Butler, I.; Christie, H.; Halligan, S.L. Parental responses to child experiences of trauma following presentation at emergency departments: A qualitative study. BMJ Open 2016, 6, e012944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bryant, R.A.; Edwards, B.; Creamer, M.; O’Donnell, M.; Forbes, D.; Felmingham, K.L.; Silove, D.; Steel, Z.; Nickerson, A.; McFarlane, A.C.; et al. The effect of posttraumatic stress disorder on refugees’ parenting and their children’s mental health: A cohort study. Lancet Public Health 2018, 3, e249–e258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Creech, S.K.; Misca, G. Parenting with PTSD: A review of research on the influence of PTSD on parent-child functioning in military and veteran families. Front. Psychol. 2017, 8, 1101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sherman, M.D.; Gress Smith, J.L.; Straits-Troster, K.; Larsen, J.L.; Gewirtz, A. Veterans’ perceptions of the impact of PTSD on their parenting and children. Psychol. Serv. 2016, 13, 401–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brunet, A.; Weiss, D.S.; Metzler, T.J.; Best, S.R.; Neylan, T.C.; Rogers, C.; Fagan, J.; Marmar, C.R. The peritraumatic distress inventory: A proposed measure of PTSD Criterion A2. Am. J. Psychiatry 2001, 158, 1480–1485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cénat, J.M.; Derivois, D. Assessment of prevalence and determinants of posttraumatic stress disorder and depression symptoms in adults survivors of earthquake in Haiti after 30 months. J. Affect. Disord. 2014, 159, 111–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weathers, F.W.; Litz, B.T.; Keane, T.M.; Palmieri, P.A.; Marx, B.P.; Schnurr, P.P. The PTSD Checklist for DSM-5 (PCL-5); National Center for PTSD: White River Junction, VT, USA, 2013. Available online: https://www.ptsd.va.gov/professional/assessment/adult-sr/ptsd-checklist.asp (accessed on 10 October 2024).

- Blevins, C.A.; Weathers, F.W.; Davis, M.T.; Witte, T.K.; Domino, J.L. The Posttraumatic Stress Disorder Checklist for DSM-5 (PCL-5): Development and initial psychometric evaluation. J. Trauma. Stress 2015, 28, 489–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cloitre, M.; Shevlin, M.; Brewin, C.R.; Bisson, J.I.; Roberts, N.P.; Maercker, A.; Karatzias, T.; Hyland, P. The International Trauma Questionnaire: Development of a self-report measure of ICD-11 PTSD and Complex PTSD. Acta Psychiatr. Scand. 2018, 138, 536–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lueger-Schuster, B.; Negrão, M.; Veiga, E.; Henley, S.; Rocha, J. International Trauma Questionnaire—Caregiver Version (ITQ-CG), Unpublished measure. 2023.

- Agley, J.; Xiao, Y.; Nolan, R.; Golzarri-Arroyo, L. Quality control questions on Amazon’s Mechanical Turk (MTurk): A randomized trial of impact on the USAUDIT, PHQ-9, and GAD-7. Behav. Res. Methods 2022, 54, 885–897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teitcher, J.; Bockting, W.O.; Bauermeister, J.A.; Hoefer, C.J.; Miner, M.H.; Klitzman, R.L. Detecting, preventing, and responding to “fraudsters” in internet research: Ethics and tradeoffs. J. Law Med. Ethics 2015, 43, 116–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tabachnick, B.G.; Fidell, L.S. Using Multivariate Statistics, 6th ed.; Pearson: Boston, MA, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Fisher, R.A. On the “Probable Erro” of a Coefficient of Correlation Deduced from a Small Sample. Metron 1921, 1, 3–32. [Google Scholar]

- Hayes, A.F. Introduction to Mediation, Moderation, and Conditional Process Analysis: A Regression-Based Approach, 3rd ed.; Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Lowe, S.R.; Sampson, L.; Young, M.N.; Galea, S. Alcohol and nonmedical prescription drug use to cope with posttraumatic stress disorder symptoms: An analysis of hurricane sandy survivors. Subst. Use Misuse 2017, 52, 1348–1356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuhan, J.; Wang, D.C.; Canada, A.; Schwartz, J. Growth after trauma: The role of self-compassion following Hurricane Harvey. Trauma Care 2021, 1, 119–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sölva, K.; Haselgruber, A.; Lueger-Schuster, B. Resilience in the face of adversity: Classes of positive adaptation in trauma-exposed children and adolescents in residential care. BMC Psychol. 2023, 11, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paquin, V.; Elgbeili, G.; Laplante, D.P.; Kildea, S.; King, S. Positive cognitive appraisal “buffers” the long-term effect of peritraumatic distress on maternal anxiety: The Queensland Flood Study. J. Affect. Disord. 2021, 278, 5–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verstraeten, B.S.; Elgbeili, G.; Hyde, A.; King, S.; Olson, D.M. Maternal mental health after a wildfire: Effects of social support in the Fort McMurray Wood Buffalo study. Can. J. Psychiatry 2021, 66, 710–718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kulkarni, P.A.; Gu, H.; Tsai, S.; Passannante, M.; Kim, S.; Thomas, P.A.; Tan, C.G.; Davidow, A.L. Evacuations as a result of hurricane Sandy: Analysis of the 2014 New Jersey behavioral risk factor survey. Disaster Med. Public Health Prep. 2017, 11, 720–728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tolin, D.F.; Foa, E.B. Sex differences in trauma and posttraumatic stress disorder: A quantitative review of 25 years of research. Psychol. Bull. 2006, 132, 959–992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yazawa, A.; Aida, J.; Kondo, K.; Kawachi, I. Gender differences in risk of posttraumatic stress symptoms after disaster among older people: Differential exposure or differential vulnerability? J. Affect. Disord. 2022, 297, 447–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- May, C.L.; Wisco, B.E. Defining trauma: How level of exposure and proximity affect risk for posttraumatic stress disorder. Psychol. Trauma Theory Res. Pract. Policy 2016, 8, 233–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asthana, T.; Krim, H.; Sun, X.; Roheda, S.; Xie, L. Atlantic hurricane activity prediction: A machine learning approach. Atmosphere 2021, 12, 455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rundle, J.B.; Stein, S.; Donnellan, A.; Turcotte, D.L.; Klein, W.; Saylor, C. The complex dynamics of earthquake fault systems: New approaches to forecasting and nowcasting of earthquakes. Rep. Prog. Phys. 2021, 84, 076801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallo, A.; Wertz, C.; Kairis, S.; Blavier, A. Exploration of relationship between parental distress, family functioning and post-traumatic symptoms in children. Eur. J. Trauma Dissociation 2019, 3, 125–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Exenberger, S.; Riedl, D.; Rangaramanujam, K.; Amirtharaj, V.; Juen, F. A cross-sectional study of mother-child agreement on PTSD symptoms in a South Indian post-tsunami sample. BMC Psychiatry 2019, 19, 414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).