Symptoms of PTSD and Depression among Central American Immigrant Youth

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Traumatic Stressors

1.2. Mental Health among Immigrants

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

3.1. Traumatic Experiences

3.1.1. Carlos

“They wanted to force me to join the Maras. And that is why you can’t study: because I was scared to leave the house … to go to school.”

“They only followed me once, but they didn’t get me. I headed home. If someone doesn’t join the Maras, they kill you, young. There are no options. If you don’t join the Maras, they kill you. I felt a lot of pressure.”

“Fleeing the Maras. It was my idea to come … My dad paid so that they [the coyotes] could bring me. From El Salvador, I went to Guatemala; from Guatemala, I took a bus. I got off, took another bus, got off. At night the buses ran… I must’ve taken around twenty buses from Guatemala to Mexico. From Mexico to the United States, I went by bus and by taxi. I crossed the border and was walking when they detained me. They took me to Immigration; they interviewed me. I explained my case, why I came… I was at the center for minors for about half a month. I played there, they had classes, and from there I went with my dad. The trip took around three months … I was in a migration center, but not the Court. I understood the rules: I shouldn’t miss school, I shouldn’t work… mostly that… In the center for minors, they treated me well. In the immigration center, they speak very angrily to you. I felt nervous because they spoke to me very angrily.”

3.1.2. Diana

“No, we go to the court, and then, they don’t tell us anything. The lawyer said that they weren’t going to give us anything, that I mean, we didn’t have hopes that they would give us, I don’t know, a permit [to stay].”

“I came from El Salvador because I wanted to study more. I want to be a doctor. Where I was living then, the schools aren’t great. Well, they don’t teach a lot of things, like math, or things like that. They only taught us math twice a week, for 30 min. Same with science. So, my parents wanted me to come here to study, and I also wanted to study, but where I lived, I couldn’t study what I wanted to study.”

“Here I think when I’m 22, or when I’m no longer a minor, I’ll be going to university. I want to study. And where I used to live was very dangerous, and there are no opportunities to pursue higher education. Most people in my country only study up to high school and stop there. It is very rare that someone makes it to university.”

“We were in a house, and then a man told us that he was going to leave us in a forest. There was a forest, and you could hear a river. And we were on a rock with some other men, who were also with the man who brought us. And you could hear animal noises, and they were very scary. We were scared. It was around 5 in the morning, and we were there for around two hours waiting for the man who was supposed to guide us across. We passed the river once, but then that was when we were going to walk along in the desert. Then we came back and did another loop because the man made a mistake, and he said that we were going to pass through there to Mexico. So, then we came back to go through the United States, and the man was mistaken again. So, then we came back to Mexico, and then the next time we crossed it was where cotton was being grown, and then we walked a lot, a lot to get to a big, black gate where there was an immigration van waiting, and they detained us. They asked our names, and they loaded us in their car, and took us to a little house where there were only around 15 girls. They gave me a blanket, around, well it must’ve already been nighttime by then. They took us to shower, because our clothes were all [dirty], and they gave us [new] clothes. The next day they took us to the detention center.”

“It was very taxing. At first, I did not want to go out. I was afraid of people who I thought did not speak Spanish. I don’t know, I thought they would say go, you aren’t from here, things like that. And I didn’t want to go to school, I felt sad. But after the first day I went to school, I made friends and then I didn’t even want there to be a weekend. I only wanted to be in school. Because we played. And although some classes/subjects were difficult for me, like math, because let me tell you, in El Salvador, they barely had taught me how to add. I didn’t know how to multiply, I didn’t know how to divide, I didn’t know anything! I only knew how to read, but I didn’t read very well. And here they taught me in Spanish. They are teaching me how to read better. And I am interested in school here. They have a lot of programs to help us, for the students at our school.”

3.1.3. Samantha

“And they went around in cars too, with firearms and all that. They would go in front of cars and wouldn’t let them pass. Supposedly, that post is controlled by them. In which country was this? Guatemala, and I think it was on the border with Mexico. And if you didn’t pay them a certain quantity of money, they wouldn’t let you through. Supposedly, they were going to set the buses on fire because they were locked from the outside. I mean, no one from the inside could open the doors or anything. The others couldn’t open them or anything. How was this problem resolved? I don’t know how they resolved it. They, I think they went back to where they came from. We were left at that sports field, that I told you about. We slept and spent around four days there, sleeping in the cold and everything. They made an agreement with them. And they gave them, the people that had to give them money, I believe a week. And if not, well that they’d do away with us. Uh-huh, and I think they were able to get it and afterwards we were let free. And we left.”

3.2. Self-Reported Mental Health

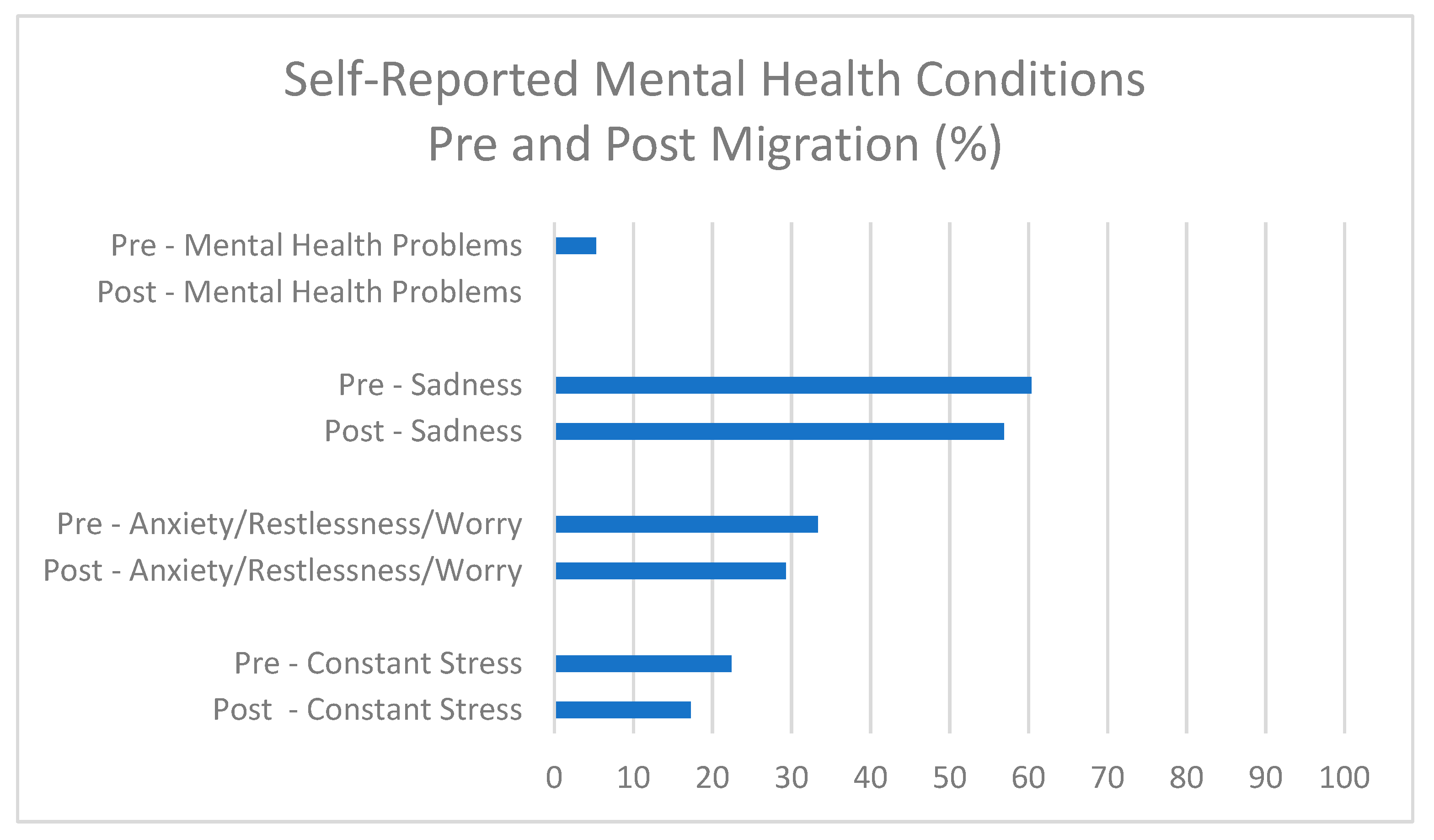

3.3. Mental Health Conditions Pre- and Post-Migration

3.4. PHQ-9 Modified for Teens

3.5. Child PTSD Symptoms Scale

4. Discussion

4.1. Traumatic Experiences

4.2. Self-Reported Mental Health

4.3. Mental Health Pre- and Post-Migration

4.4. PHQ-8

4.5. Child PTSD Symptoms Scale

5. Limitations

6. Conclusions: The Social Determinants of Mental Health

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Correction Statement

References

- Alegria, M.; Shrout, P.E.; Woo, M.; Guarnaccia, P.; Sribney, W.; Vila, D.; Polo, A.; Cao, Z.; Mulvaney-Day, N.; Torres, M.; et al. Understanding Differences in Past Year Psychiatric Disorders for Latinos Living in the US. Soc. Sci. Med. 2007, 65, 214–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cervantes, R.C.; Gattamorta, K.A.; Berger-Cardoso, J. Examining Difference in Immigration Stress, Acculturation Stress and Mental Health Outcomes in Six Hispanic/Latino Nativity and Regional Groups. J. Immigr. Minority Health 2019, 21, 14–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hynie, M. The Social Determinants of Refugee Mental Health in the Post-Migration Context: A Critical Review. Can. J. Psychiatry 2018, 63, 297–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castaneda, E.; Buck, L. A Family of Strangers: Transnational Parenting and the Consquences of Family Separation Due to Undocumented Migration. In Hidden Lives and Human Rights in the United States: Understanding the Controversies and Tragedies of Undocumented Immigration; Lorentzen, L.A., Ed.; Praeger, an imprint of ABC-CLIO, LLC: Santa Barbara, CA, USA, 2014; Volume 2, pp. 175–201. ISBN 978-1-4408-2847-8. [Google Scholar]

- Abrego, L.J. Sacrificing Families: Navigating Laws, Labor, and Love Across Borders; Stanford University Press: Stanford, CA, USA, 2014; ISBN 978-0-8047-9057-4. [Google Scholar]

- Oliveira, G. Motherhood Across Borders: Immigrants and Their Children in Mexico and New York; NYU Press: New York, NY, USA, 2018; ISBN 978-1-4798-7462-0. [Google Scholar]

- Parreñas, R.S. Migrant Filipina Domestic Workers and the International Division of Reproductive Labor. Gend. Soc. 2000, 14, 560–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castañeda, E.; Buck, L. Remittances, Transnational Parenting, and the Children Left Behind: Economic and Psychological Implications. Lat. Am. 2011, 55, 85–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alegría, M.; NeMoyer, A.; Falgas, I.; Wang, Y.; Alvarez, K. Social Determinants of Mental Health: Where We Are and Where We Need to Go. Curr. Psychiatry Rep. 2018, 20, 95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pai, A.; Suris, A.M.; North, C.S. Posttraumatic Stress Disorder in the DSM-5: Controversy, Change, and Conceptual Considerations. Behav. Sci. 2017, 7, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Torres, S.A.; Santiago, C.D.; Walts, K.K.; Richards, M.H. Immigration Policy, Practices, and Procedures: The Impact on the Mental Health of Mexican and Central American Youth and Families. Am. Psychol. 2018, 73, 843–854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berger Cardoso, J.; Brabeck, K.; Stinchcomb, D.; Heidbrink, L.; Price, O.A.; Gil-García, Ó.F.; Crea, T.M.; Zayas, L.H. Integration of Unaccompanied Migrant Youth in the United States: A Call for Research. J. Ethn. Migr. Stud. 2019, 45, 273–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stinchcomb, D.; Hershberg, E. Unaccompanied Migrant Children from Central America: Context, Causes, and Responses; Social Science Research Network: Rochester, NY, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Semple, K. Migrants in Mexico Face Kidnappings and Violence While Awaiting Immigration Hearings in U.S. The New York Times 2019. Available online: https://www.nytimes.com/2019/07/12/world/americas/mexico-migrants.html (accessed on 30 March 2021).

- Chomsky, A. Undocumented: How Immigration Became Illegal; Beacon Press: Boston, MA, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Castañeda, E. Living in Limbo: Transnational Households, Remittances and Development. Int. Migr. 2013, 51, 13–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dreby, J. Divided by Borders: Mexican Migrants and Their Children; University of California Press: Berkeley, CA, USA, 2010; ISBN 9780520266605. [Google Scholar]

- Parreñas, R.S. Children of Global Migration: Transnational Families and Gendered Woes; Stanford University Press: Stanford, CA, USA, 2005; ISBN 0804749442. [Google Scholar]

- Dreby, J. U.S. Immigration Policy and Family Separation: The Consequences for Children’s Well-Being. Soc. Sci. Med. 2015, 132, 245–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deparle, J. A Good Provider Is One Who Leaves: One Family and Migration in the 21st Century; Penguin Publishing Group: New York, NY, USA, 2020; ISBN 978-0-14-311119-1. [Google Scholar]

- Walker, J.; Venta, A.; Galicia, B. Who Is Taking Care of Central American Immigrant Youth? Preliminary Data on Caregiving Arrangements and Emotional-Behavioral Symptoms Post-Migration. Child. Psychiatry Hum. Dev. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venta, A.C.; Mercado, A. Trauma Screening in Recently Immigrated Youth: Data from Two Spanish-Speaking Samples. J. Child. Fam Stud. 2019, 28, 84–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breslau, J.; Borges, G.; Tancredi, D.; Saito, N.; Kravitz, R.; Hinton, L.; Vega, W.; Medina-Mora, M.E.; Aguilar-Gaxiola, S. Migration from Mexico to the United States and Subsequent Risk for Depressive and Anxiety Disorders: A Cross-National Study. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 2011, 68, 428–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jamil, H.; Farrag, M.; Hakim-Larson, J.; Kafaji, T.; Abdulkhaleq, H.; Hammad, A. Mental Health Symptoms in Iraqi Refugees: Posttraumatic Stress Disorder, Anxiety, and Depression. J. Cult. Divers. 2007, 14, 19–25. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Park, J.; Elbert, T.; Kim, S.J.; Park, J. The Contribution of Posttraumatic Stress Disorder and Depression to Insomnia in North Korean Refugee Youth. Front. Psychiatry 2019, 10, 211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reavell, J.; Fazil, Q. The Epidemiology of PTSD and Depression in Refugee Minors Who Have Resettled in Developed Countries. J. Ment. Health 2017, 26, 74–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perreira, K.M.; Ornelas, I. Painful Passages: Traumatic Experiences and Post-Traumatic Stress among U.S. Immigrant Latino Adolescents and Their Primary Caregivers. Int. Migr. Rev. 2013, 47, 976–1005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castañeda, E. Building Walls: Excluding Latin People in the United States; Lexington: Lanham, MD, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Androff, D.K.; Ayon, C.; Becerra, D.; Gurrola, M. U.S. Immigration Policy and Immigrant Children’s Well-Being: The Impact of Policy Shifts. J. Soc. Soc. Welf. 2011, 38, 77–98. [Google Scholar]

- Romero, M. Are Your Papers in Order: Racial Profiling, Vigilantes, and America’s Toughest Sheriff. Harv. Lat. L. Rev. 2011, 14, 337. [Google Scholar]

- Luo, T.; Escalante, C.L. Stringent Immigration Enforcement and the Mental Health and Health-Risk Behaviors of Hispanic Adolescent Students in Arizona. Health Econ. 2021, 30, 86–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaltman, S.; de Mendoza, A.H.; Gonzales, F.A.; Serrano, A.; Guarnaccia, P.J. Contextualizing the Trauma Experience of Women Immigrants from Central America, South America, and Mexico. J. Trauma. Stress 2011, 24, 635–642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Holmes, W.C.; Slap, G.B. Sexual Abuse of Boys: Definition, Prevalence, Correlates, Sequelae, and Management. JAMA 1998, 280, 1855–1862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hovey, J.D. Acculturative Stress, Depression, and Suicidal Ideation among Central American Immigrants. Suicide Life Threat. Behav. 2000, 30, 125–139. [Google Scholar]

- Cook, B.; Alegría, M.; Lin, J.Y.; Guo, J. Pathways and Correlates Connecting Latinos’ Mental Health With Exposure to the United States. Am. J. Public Health 2009, 99, 2247–2254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moya, E.M.; Chávez-Baray, S.M.; Esparza, O.A.; Chelius, L.C.; Castañeda, E.; Villalobos, G.; Eguiluz, I.; Martínez, E.A.; Herrera, K.; Llamas, T.; et al. Ulysses Syndrome in Economical and Political Migrants in Mexico and the United States. EHQUIDAD Rev. Int. De Políticas De Bienestar Y Trab. Soc. 2016, 5, 11–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Achotegui, J. How to Assess. Stress and Migratory Mourning: Scales of Risk Factors in Mental Health; Ediciones El Mundo de la Mente: Llançà, España, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Finch, B.K.; Kolody, B.; Vega, W.A. Perceived Discrimination and Depression among Mexican-Origin Adults in California. J. Health Soc. Behav. 2000, 41, 295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Umaña-Taylor, A.J.; Updegraff, K.A. Latino Adolescents’ Mental Health: Exploring the Interrelations among Discrimination, Ethnic Identity, Cultural Orientation, Self-Esteem, and Depressive Symptoms. J. Adolesc. 2007, 30, 549–567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szalacha, L.A.; Erkut, S.; Coll, C.G.; Alarcón, O.; Fields, J.P.; Ceder, I. Discrimination and Puerto Rican Children’s and Adolescents’ Mental Health. Cult. Divers. Ethn. Minority Psychol. 2003, 9, 141–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leong, F.; Park, Y.S.; Kalibatseva, Z. Disentangling Immigrant Status in Mental Health: Psychological Protective and Risk Factors among Latino and Asian American Immigrants. Am. J. Orthopsychiatry 2013, 83, 361–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arbona, C.; Olvera, N.; Rodriguez, N.; Hagan, J.; Linares, A.; Wiesner, M. Acculturative Stress Among Documented and Undocumented Latino Immigrants in the United States. Hisp J. Behav Sci 2010, 32, 362–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dunn, M.G.; O’Brien, K.M. Psychological Health and Meaning in Life: Stress, Social Support, and Religious Coping in Latina/Latino Immigrants. Hisp. J. Behav. Sci. 2009, 31, 204–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hochhausen, L.; Le, H.; Perry, D.F. Community-Based Mental Health Service Utilization Among Low-Income Latina Immigrants. Community Ment. Health J. 2011, 47, 14–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Castañeda, E. There is No Immigration Security Threat That Reform with an Earned Path to Citizenship Cannot Address. Available online: https://scholars.org/there-no-immigration-security-threat-reform-earned-path-citizenship-cannot-address (accessed on 14 October 2020).

- Mangual Figueroa, A.; Barrales, W. Testimonio and Counterstorytelling by Immigrant-Origin Children and Youth: Insights That Amplify Immigrant Subjectivities. Societies 2021, 11, 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boehm, D.A.; Terrio, S.J. Illegal Encounters: The Effect of Detention and Deportation on Young People; NYU Press: New York, NY, USA, 2019; ISBN 978-1-4798-0591-4. [Google Scholar]

- Terrio, S.J. Whose Child. Am. I? Unaccompanied, Undocumented Children in U.S. Immigration Custody; University of California Press: Oakland, CA, USA, 2015; ISBN 978-0-520-28149-3. [Google Scholar]

- Rung, D.L. Processes of Sub-Citizenship: Neoliberal Statecrafting ‘Citizens,’ ‘Non-Citizens,’ and Detainable ‘Others’. Soc. Sci. 2020, 9, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Small, M.L. How to Conduct a Mixed Methods Study: Recent Trends in a Rapidly Growing Literature. Annu. Rev. Sociol. 2011, 37, 57–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Creswell, J.W.; Clark-Plano, V.L. Choosing a Mixed Methods Design. In Designing and Conducting: Mixed Methods Research; SAGE Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2007; pp. 58–88. [Google Scholar]

- Rumbaut, R.G. Sites of Belonging: Acculturation, Discrimination, and Ethnic Identity Among Children of Immigrants. In Discovering Successful Pathways in Children’s Development: Mixed Methods in the Study of Childhood and Family Life; Weiner, T.S., Ed.; University of Chicago Press: Chicago, IL, USA, 2005; pp. 111–164. [Google Scholar]

- Zamora-Kapoor, A.; Castañeda, E. Using Mixed Methods in Comparative Research: A Cross-Regional Analysis of Anti-Immigrant Sentiment in Belgium and Spain; SAGE: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Castañeda, E.; Morales, C.; Ochoa, O. Transnational Behavior in Comparative Perspective: The Relationship between Immigrant Integration and Transnationalism in New York, El Paso, and Paris. Comp. Migr. Stud. 2014, 2, 305–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canizales, S.; Diaz-Strong, D. Undocumented Childhood Arrivals in the U.S.: Widening the Frame for Research and Policy; Immigration Initiative at Harvard Issue Brief Series; Harvard University: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Kroenke, K.; Spitzer, R.L.; Williams, J.B.W. The PHQ-9. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 2001, 16, 606–613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuestionario Sobre La Salud Del Paciente-9 2005. Available online: http://www.ocagingservicescollaborative.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/07/PHQ9-Spanish.pdf (accessed on 1 April 2021).

- Serrano-Ibáñez, E.R.; Ruiz-Párraga, G.T.; Esteve, R. Validation of the Child PTSD Symptom Scale (CPSS) in Spanish Adolescents. Psicothema 2018, 130–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diez-Quevedo, C.; Rangil, T.; Sanchez-Planell, L.; Kroenke, K.; Spitzer, R.L. Validation and Utility of the Patient Health Questionnaire in Diagnosing Mental Disorders in 1003 General Hospital Spanish Inpatients. Psychosom. Med. 2001, 63, 679–686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kroenke, K.; Spitzer, R. The PHQ-9: A New Depression Diagnostic and Severity Measure. Psychiatr. Ann. 2002, 32, 509–521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cognitive Behavioral Intervention for Trauma in Schools CBITS | Forms. Available online: https://cbitsprogram.org/forms (accessed on 30 March 2021).

- Foa, E.B.; Johnson, K.M.; Feeny, N.C.; Treadwell, K.R.H. The Child PTSD Symptom Scale: A Preliminary Examination of Its Psychometric Properties. J. Clin. Child. Adolesc. Psychol. 2001, 30, 376–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patler, C.; Hamilton, E.R.; Savinar, R.L. The Limits of Gaining Rights While Remaining Marginalized: The Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals (DACA) Program and the Psychological Wellbeing of Latina/o Undocumented Youth. Soc. Forces 2021, 100, 246–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menjívar, C. Liminal Legality: Salvadoran and Guatemalan Immigrants’ Lives in the United States. Am. J. Sociol. 2006, 111, 999–1037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mendoza, H.; Masuda, A.; Swartout, K.M. Mental Health Stigma and Self-Concealment as Predictors of Help-Seeking Attitudes among Latina/o College Students in the United States. Int J. Adv. Couns. 2015, 37, 207–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wainberg, M.L.; Scorza, P.; Shultz, J.M.; Helpman, L.; Mootz, J.J.; Johnson, K.A.; Neria, Y.; Bradford, J.-M.E.; Oquendo, M.A.; Arbuckle, M.R. Challenges and Opportunities in Global Mental Health: A Research-to-Practice Perspective. Curr. Psychiatry Rep. 2017, 19, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mikolajczak, M.; Petrides, K.M.; Hurry, J. Adolescents Choosing Self-Harm as an Emotion Regulation Strategy: The Protective Role of Trait Emotional Intelligence. Br. J. Clin. Psychol. 2009, 48, 181–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zimmermann, P.; Iwanski, A. Emotion Regulation from Early Adolescence to Emerging Adulthood and Middle Adulthood: Age Differences, Gender Differences, and Emotion-Specific Developmental Variations. Int. J. Behav. Dev. 2014, 28, 182–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abramson, A. Fear of Deportation Has Heartbreaking Mental Health Repercussions. Available online: https://www.brit.co/fear-of-deportation-has-heartbreaking-mental-health-repercussions/ (accessed on 26 March 2021).

- Abramson, A. US Border Officials Are Creating Lifelong Trauma for Child Migrants by Separating Them from Their Families. Available online: https://www.brit.co/us-border-officials-are-creating-lifelong-trauma-for-child-migrants-by-separating-them-from-their-families/ (accessed on 26 March 2021).

- Lovato, R. Unforgetting: A Memoir of Family, Migration, Gangs, and Revolution in the Americas; HarperCollins: New York, NY, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Haslam, N.; Dakin, B.C.; Fabiano, F.; McGrath, M.J.; Rhee, J.; Vylomova, E.; Weaving, M.; Wheeler, M.A. Harm Inflation: Making Sense of Concept Creep. Eur. Rev. Soc. Psychol. 2020, 31, 254–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciftci, A.; Jones, N.; Corrigan, P.W. Mental Health Stigma in the Muslim Community. Stigma 2012, 7, 17–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bermúdez, J.M.; Kirkpatrick, D.R.; Hecker, L.; Torres-Robles, C. Describing Latinos Families and Their Help-Seeking Attitudes: Challenging the Family Therapy Literature. Contemp. Fam. 2010, 32, 155–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rastogi, M.; Massey-Hastings, N.; Wieling, E. Barriers to Seeking Mental Health Services in the Latino/a Community: A Qualitative Analysis. J. Syst. Ther. 2012, 31, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drew, N.; Funk, M.; Tang, S.; Lamichhane, J.; Chávez, E.; Katontoka Dip, S.; Pathare, S.; Lewis, O.; Gostin, L.; Saraceno, B. Human Rights Violations of People with Mental and Psychosocial Disabilities: An Unresolved Global Crisis. Lancet 2011, 378, 1664–1675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marshall, G.N.; Schell, T.L.; Miles, J.N.V. All PTSD Symptoms Are Highly Associated with General Distress: Ramifications for the Dysphoria Symptom Cluster. J. Abnorm. Psychol. 2010, 119, 126–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Millgram, Y.; Joormann, J.; Huppert, J.D.; Lampert, A.; Tamir, M. Motivations to Experience Happiness or Sadness in Depression: Temporal Stability and Implications for Coping With Stress. Clin. Psychol. Sci. 2019, 7, 143–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Winkel, M.; Nicolson, N.A.; Wichers, M.; Viechtbauer, W.; Myin-Germeys, I.; Peeters, F. Daily Life Stress Reactivity in Remitted Versus Non-Remitted Depressed Individuals. Eur. Psychiatry 2015, 30, 441–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castañeda, E.; Smith, B.; Vetter, E. Hispanic Health Disparities and Housing: Comparing Measured and Self-Reported Health Metrics among Housed and Homeless Latin Individuals. J. Migr. Health 2020, 1–2, 100008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Overall | ||

|---|---|---|

| n | Years/% | |

| Average age at time of arrival | 58 | 14 |

| Average age at time of interview | 58 | 16 |

| Gender | 58 | |

| Male | 31 | 53.5% |

| Female | 26 | 44.8% |

| Non-binary | 1 | 1.7% |

| U.S. legal citizenship status at time of arrival | 58 | |

| Documented | 9 | 15.5% |

| Undocumented | 49 | 84.5% |

| Country of origin | 58 | |

| El Salvador | 37 | 63.8% |

| Honduras | 16 | 27.6% |

| Guatemala | 5 | 8.6% |

| Jurisdiction within DC metropolitan area | 58 | |

| Prince George’s County | 22 | 37.9% |

| Montgomery County | 24 | 41.4% |

| Fairfax County | 12 | 20.7% |

| Accompaniment status at the border | 58 | |

| Accompanied | 34 | 58.6% |

| Unaccompanied | 24 | 41.4% |

| SCORING | SEVERITY |

|---|---|

| 0–4 | No or minimal depression |

| 5–9 | Mild depression |

| 10–14 | Moderate depression |

| 15–19 | Moderately severe depression |

| 20–24 | Severe depression |

| Add the Number of Points Endorsed Per Question, Where | |

|---|---|

| 1 | not at all = 0 points, once in a while = 1 point, half the time = 2 points, and almost always = 3 points. |

| 2 | Tally all points for each of the 17 questions to obtain a total score. |

| 3 | Total scores of 14 points or higher indicate moderate to severe PTSD. |

| Reasons before Migration | Reasons after Migration | |

|---|---|---|

| Constant stress |

|

|

| Anxiety |

|

|

| Sadness |

|

|

| Mental health problems |

|

|

| N | Percent | |

|---|---|---|

| No or minimal | 46 | 79.3 |

| Mild | 8 | 13.8 |

| Moderate | 4 | 6.9 |

| n | 58 | 100 |

| N | Percent | |

|---|---|---|

| Zero | 7 | 12.3 |

| Low | 31 | 54.4 |

| Moderate to Severe | 19 | 33.3 |

| n | 57 | 100 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Castañeda, E.; Jenks, D.; Chaikof, J.; Cione, C.; Felton, S.; Goris, I.; Buck, L.; Hershberg, E. Symptoms of PTSD and Depression among Central American Immigrant Youth. Trauma Care 2021, 1, 99-118. https://doi.org/10.3390/traumacare1020010

Castañeda E, Jenks D, Chaikof J, Cione C, Felton S, Goris I, Buck L, Hershberg E. Symptoms of PTSD and Depression among Central American Immigrant Youth. Trauma Care. 2021; 1(2):99-118. https://doi.org/10.3390/traumacare1020010

Chicago/Turabian StyleCastañeda, Ernesto, Daniel Jenks, Jessica Chaikof, Carina Cione, SteVon Felton, Isabella Goris, Lesley Buck, and Eric Hershberg. 2021. "Symptoms of PTSD and Depression among Central American Immigrant Youth" Trauma Care 1, no. 2: 99-118. https://doi.org/10.3390/traumacare1020010

APA StyleCastañeda, E., Jenks, D., Chaikof, J., Cione, C., Felton, S., Goris, I., Buck, L., & Hershberg, E. (2021). Symptoms of PTSD and Depression among Central American Immigrant Youth. Trauma Care, 1(2), 99-118. https://doi.org/10.3390/traumacare1020010