Automated Scale-Down Development and Optimization of [68Ga]Ga-DOTA-EMP-100 for Non-Invasive PET Imaging and Targeted Radioligand Therapy of c-MET Overactivation in Cancer

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

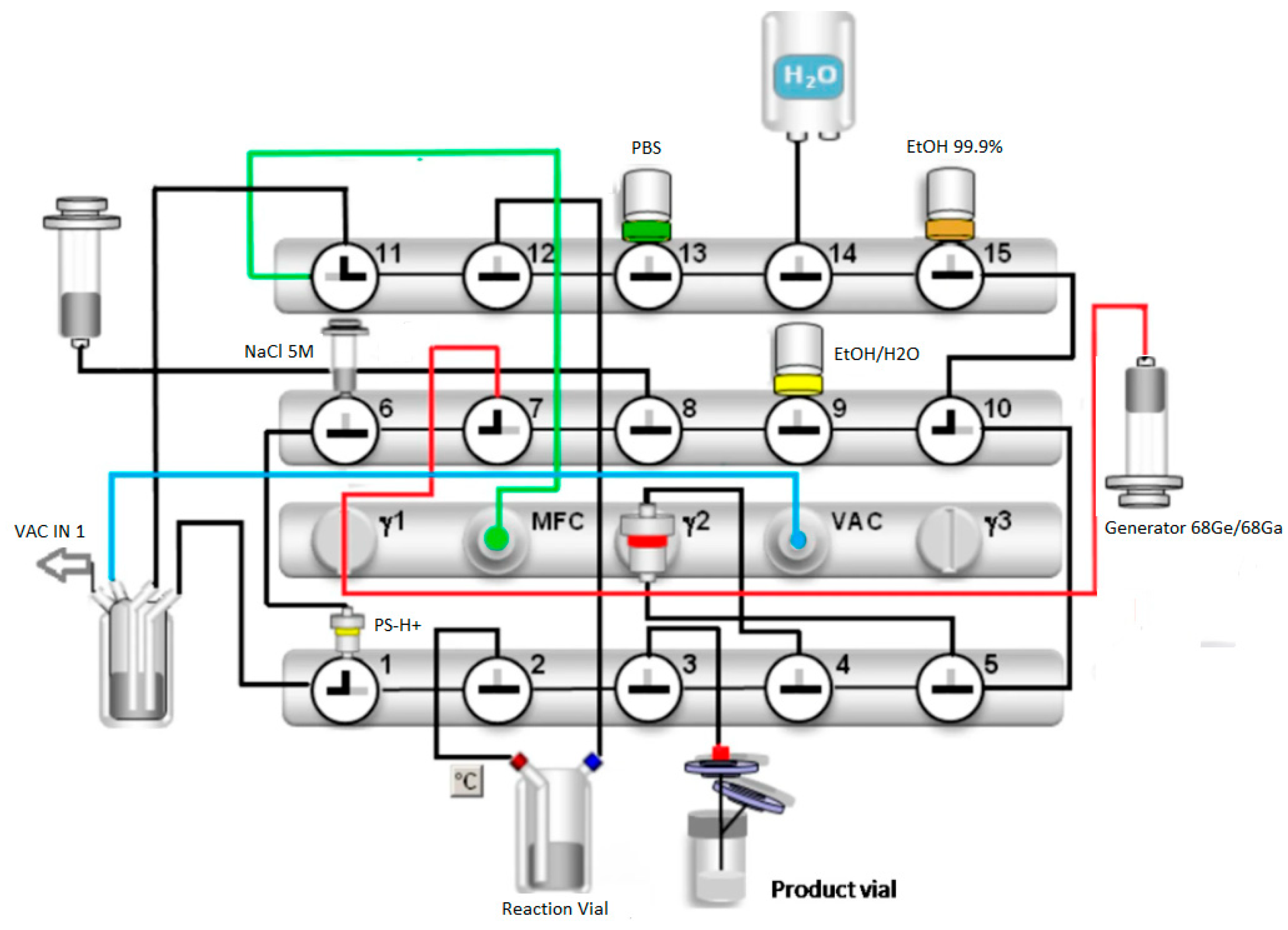

2.1. Radiosynthesis

2.2. Quality Control and Process Validation

2.3. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

Labelling and Quality Control Results for Different DOTA-EMP-100 Loads and the Validated Synthesis

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| As | Specific activity |

| CT | Computed tomography |

| GMP | Good manufacturing practice |

| GRP | Good radiopharmaceutical practices |

| EANM | European Association of Nuclear Medicine |

| Eur. Ph. | European Pharmacopeia |

| HEPES | 2-[4-(2-hydroxyethyl)-1-piperazinyl]-ethanesulfonic acid |

| HPLC | High-pressure liquid chromatography |

| NBP | Norme di Buona Preparazione in Nuclear Medicine |

| TLC | Thin-layer chromatography |

| TFA | Trifluoroacetic acid |

| PET | Positron emission tomography |

| QC | Quality control |

| RCY | Radiochemical yield |

| RCP | Radiochemical purity |

References

- Fu, J.; Su, X.; Li, Z.; Deng, L.; Liu, X.; Feng, X.; Peng, J. HGF/c-MET pathway in cancer: From molecular characterization to clinical evidence. Oncogene 2021, 40, 4625–4651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Konstorum, A.; Lowengrub, J.S. Activation of the HGF/c-Met axis in the tumor microenvironment: A multispecies model. J. Theor. Biol. 2018, 439, 86–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Boromand, N.; Hasanzadeh, M.; ShahidSales, S.; Farazestanian, M.; Gharib, M.; Fiuji, H.; Behboodi, N.; Ghobadi, N.; Hassanian, S.M.; Ferns, G.A.; et al. Clinical and prognostic value of the C-Met/HGF signaling pathway in cervical cancer. J. Cell Physiol. 2018, 233, 4490–4496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Granito, A.; Guidetti, E.; Gramantieri, L. c-MET receptor tyrosine kinase as a molecular target in advanced hepatocellular carcinoma. J. Hepatocell. Carcinoma 2015, 2, 29–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, Z.; Xue, W.; Zheng, Y.; Geng, Q.; Wang, L.; Fan, Z.; Wang, W.; Yue, Y.; Zhai, Y.; Li, L.; et al. Molecular mechanism study of HGF/c-MET pathway activation and immune regulation for a tumor diagnosis model. Cancer Cell Int. 2021, 21, 374, Erratum in Cancer Cell Int. 2021, 21, 672. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12935-021-02359-z. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Krause, D.S.; Van Etten, R.A. Tyrosine kinases as targets for cancer therapy. N. Engl. J. Med. 2005, 353, 172–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mo, H.N.; Liu, P. Targeting MET in cancer therapy. Chronic Dis. Transl. Med. 2017, 3, 148–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Hu, C.T.; Wu, J.R.; Cheng, C.C.; Wu, W.S. The Therapeutic Targeting of HGF/c-Met Signaling in Hepatocellular Carcinoma: Alternative Approaches. Cancers 2017, 9, 58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Bradley, C.A.; Salto-Tellez, M.; Laurent-Puig, P.; Bardelli, A.; Rolfo, C.; Tabernero, J.; Khawaja, H.A.; Lawler, M.; Johnston, P.G.; Van Schaeybroeck, S.; et al. Targeting c-MET in gastrointestinal tumours: Rationale, opportunities and challenges. Nat. Rev. Clin. Oncol. 2017, 14, 562–576, Erratum in Nat. Rev. Clin. Oncol. 2018, 15, 150. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrclinonc.2018.13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, X.; Zhu, Y.; Liang, Z.; Li, S.; Xu, X.; Wang, X.; Wu, J.; Hu, Z.; Meng, S.; Liu, B.; et al. c-Met and CREB1 are involved in miR-433-mediated inhibition of the epithelial-mesenchymal transition in bladder cancer by regulating Akt/GSK-3β/Snail signaling. Cell Death Dis. 2016, 7, e2088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Furge, K.A.; Zhang, Y.W.; Vande Woude, G.F. Met receptor tyrosine kinase: Enhanced signaling through adapter proteins. Oncogene 2000, 19, 5582–5589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, X.; Sun, R.; Chen, J.; Liu, L.; Cui, X.; Shen, S.; Cui, G.; Ren, Z.; Yu, Z. Crosstalk Mechanisms Between HGF/c-Met Axis and ncRNAs in Malignancy. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2020, 8, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demkova, L.; Kucerova, L. Role of the HGF/c-MET tyrosine kinase inhibitors in metastasic melanoma. Mol. Cancer 2018, 17, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Tanaka, A.; Ogawa, M.; Zhou, Y.; Namba, K.; Hendrickson, R.C.; Miele, M.M.; Li, Z.; Klimstra, D.S.; Buckley, P.G.; Gulcher, J.; et al. Proteogenomic characterization of primary colorectal cancer and metastatic progression identifies proteome-based subtypes and signatures. Cell Rep. 2024, 43, 113810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Liu, Y.; Yu, X.F.; Zou, J.; Luo, Z.H. Prognostic value of c-Met in colorectal cancer: A meta-analysis. World J. Gastroenterol. 2015, 21, 3706–3710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Gherardi, E.; Birchmeier, W.; Birchmeier, C.; Vande Woude, G. Targeting MET in cancer: Rationale and progress. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2012, 12, 89–103, Erratum in Nat. Rev. Cancer 2012, 12, 637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Albadari, N.; Xie, Y.; Li, W. Deciphering treatment resistance in metastatic colorectal cancer: Roles of drug transports, EGFR mutations, and HGF/c-MET signaling. Front. Pharmacol. 2024, 14, 1340401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Hughes, V.S.; Siemann, D.W. Have Clinical Trials Properly Assessed c-Met Inhibitors? Trends Cancer 2018, 4, 94–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Floresta, G.; Abbate, V. Recent progress in the imaging of c-Met aberrant cancers with positron emission tomography. Med. Res. Rev. 2022, 42, 1588–1606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Luo, H.; Hong, H.; Slater, M.R.; Graves, S.A.; Shi, S.; Yang, Y.; Nickles, R.J.; Fan, F.; Cai, W. PET of c-Met in Cancer with 64Cu-Labeled Hepatocyte Growth Factor. J. Nucl. Med. 2015, 56, 758–763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Jagoda, E.M.; Lang, L.; Bhadrasetty, V.; Histed, S.; Williams, M.; Kramer-Marek, G.; Mena, E.; Rosenblum, L.; Marik, J.; Tinianow, J.N.; et al. Immuno-PET of the hepatocyte growth factor receptor Met using the 1-armed antibody onartuzumab. J. Nucl. Med. 2012, 53, 1592–1600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Arulappu, A.; Battle, M.; Eisenblaetter, M.; McRobbie, G.; Khan, I.; Monypenny, J.; Weitsman, G.; Galazi, M.; Hoppmann, S.; Gazinska, P.; et al. c-Met PET Imaging Detects Early-Stage Locoregional Recurrence of Basal-Like Breast Cancer. J. Nucl. Med. 2016, 57, 765–770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, C.; Tang, Z.; Fan, W.; Zhu, W.; Wang, C.; Somoza, E.; Owino, N.; Li, R.; Ma, P.C.; Wang, Y. In vivo positron emission tomography (PET) imaging of mesenchymal-epithelial transition (MET) receptor. J. Med. Chem. 2010, 53, 139–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Remon, J.; Hendriks, L.E.L.; Mountzios, G.; García-Campelo, R.; Saw, S.P.L.; Uprety, D.; Recondo, G.; Villacampa, G.; Reck, M. MET alterations in NSCLC-Current Perspectives and Future Challenges. J. Thorac. Oncol. 2023, 18, 419–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spigel, D.R.; Edelman, M.J.; O’Byrne, K.; Paz-Ares, L.; Mocci, S.; Phan, S.; Shames, D.S.; Smith, D.; Yu, W.; Paton, V.E.; et al. Results from the Phase III Randomized Trial of Onartuzumab Plus Erlotinib Versus Erlotinib in Previously Treated Stage IIIB or IV Non-Small-Cell Lung Cancer: METLung. J. Clin. Oncol. 2017, 35, 412–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Comoglio, P.M.; Trusolino, L.; Boccaccio, C. Known and novel roles of the MET oncogene in cancer: A coherent approach to targeted therapy. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2018, 18, 341–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, J.; Anderson, M.G.; Oleksijew, A.; Vaidya, K.S.; Boghaert, E.R.; Tucker, L.; Zhang, Q.; Han, E.K.; Palma, J.P.; Naumovski, L.; et al. ABBV-399, a c-Met Antibody-Drug Conjugate that Targets Both MET-Amplified and c-Met-Overexpressing Tumors, Irrespective of MET Pathway Dependence. Clin. Cancer Res. 2017, 23, 992–1000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sartor, O.; de Bono, J.; Chi, K.N.; Fizazi, K.; Herrmann, K.; Rahbar, K.; Tagawa, S.T.; Nordquist, L.T.; Vaishampayan, N.; El-Haddad, G.; et al. Lutetium-177-PSMA-617 for Metastatic Castration-Resistant Prostate Cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 2021, 385, 1091–1103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Strosberg, J.; El-Haddad, G.; Wolin, E.; Hendifar, A.; Yao, J.; Chasen, B.; Mittra, E.; Kunz, P.L.; Kulke, M.H.; Jacene, H.; et al. Phase 3 Trial of 177Lu-Dotatate for Midgut Neuroendocrine Tumors. N. Engl. J. Med. 2017, 376, 125–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Mittlmeier, L.M.; Todica, A.; Gildehaus, F.J.; Unterrainer, M.; Beyer, L.; Brendel, M.; Albert, N.L.; Ledderose, S.T.; Vettermann, F.J.; Schott, M.; et al. 68Ga-EMP-100 PET/CT-a novel ligand for visualizing c-MET expression in metastatic renal cell carcinoma-first in-human biodistribution and imaging results. Eur. J. Nucl. Med. Mol. Imaging 2022, 49, 1711–1720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Rusu, T.; Delion, M.; Pirot, C.; Blin, A.; Rodenas, A.; Talbot, J.N.; Veran, N.; Portal, C.; Montravers, F.; Cadranel, J.; et al. Fully automated radiolabeling of [68Ga]Ga-EMP100 targeting c-MET for PET-CT clinical imaging. EJNMMI Radiopharm. Chem. 2023, 8, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- European Directorate for the Quality of Medicines & HealthCare (EDQM). Radiopharmaceutical preparations. General Monograph No. 0125. In European Pharmacopoeia, 11th ed.; Council of Europe: Strasbourg, France, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- European Pharmacopeia. Gallium (68 Ga) chloride solution for radiolabelling. European Directorate for the Quality of Medicines. Eur. Pharm. 2013, 2464, 1060–1061. [Google Scholar]

- Migliari, S.; Sammartano, A.; Scarlattei, M.; Serreli, G.; Ghetti, C.; Cidda, C.; Baldari, G.; Ortenzia, O.; Ruffini, L. Development and Validation of a High-Pressure Liquid Chromatography Method for the Determination of Chemical Purity and Radiochemical Purity of a [68Ga]-Labeled Glu-Urea-Lys(Ahx)-HBED-CC (Positron Emission Tomography) Tracer. ACS Omega 2017, 2, 7120–7126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Migliari, S.; Scarlattei, M.; Baldari, G.; Ruffini, L. Scale down and optimized automated production of [68Ga]68Ga-DOTA-ECL1i PET tracer targeting CCR2 expression. EJNMMI Radiopharm. Chem. 2023, 8, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- European Pharmacopoeia Commission, Council of Europe. European Pharmacopoeia, 8th ed.; European Directorate for the Quality of Medicines & Health Care: Strasbourg, France, 2013. [Google Scholar]

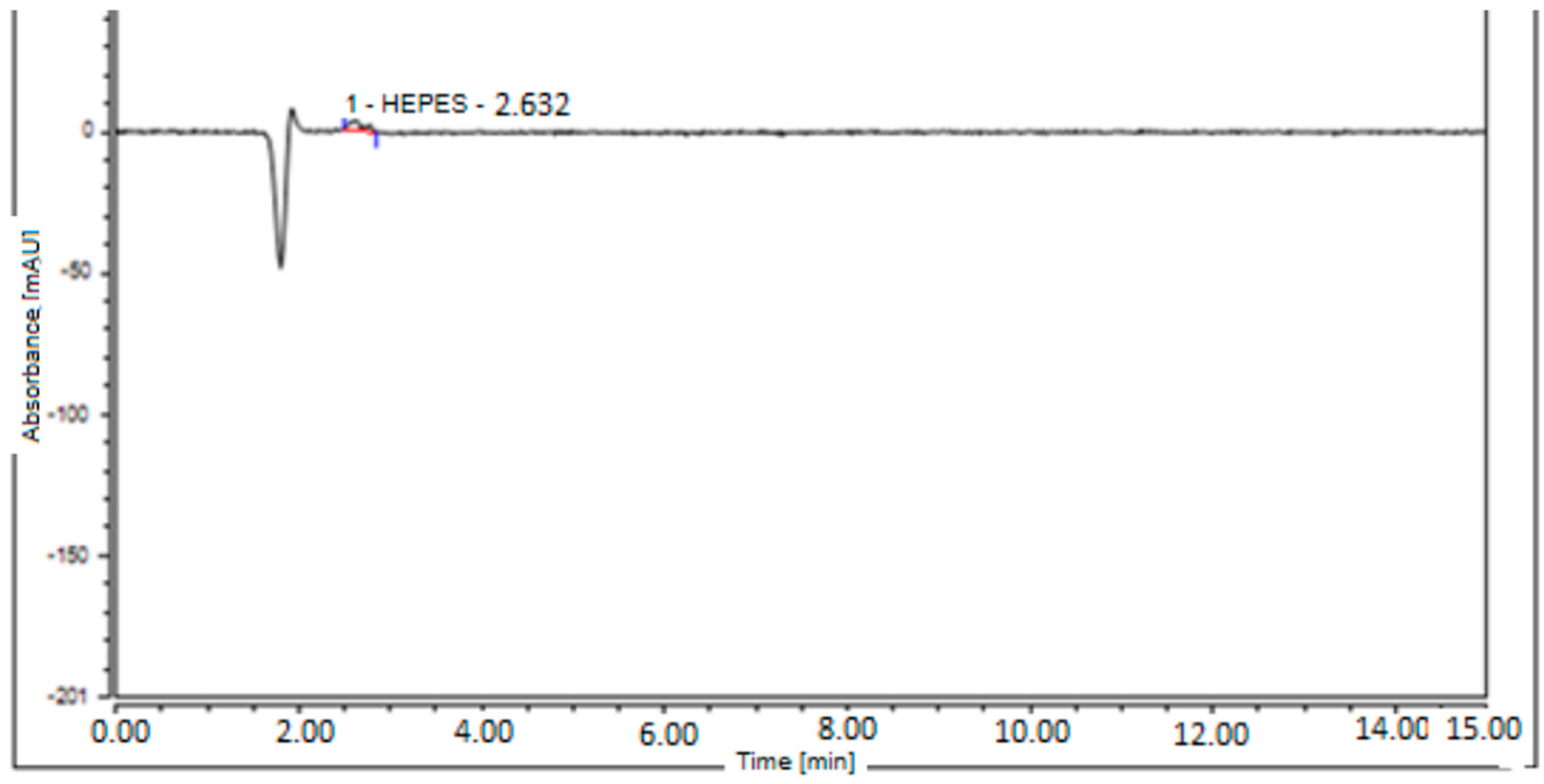

- Migliari, S.; Scarlattei, M.; Baldari, G.; Silva, C.; Ruffini, L. A specific HPLC method to determine residual HEPES in [68Ga]Ga radiopharmaceuticals: Development and validation. Molecules 2022, 27, 4477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Sinnes, J.P.; Nagel, J.; Waldron, B.P.; Maina, T.; Nock, B.A.; Bergmann, R.K.; Ullrich, M.; Pietzsch, J.; Bachmann, M.; Baum, R.P.; et al. Instant kit preparation of 68Ga-radiopharmaceuticals via the hybrid chelator DATA: Clinical translation of [68Ga]Ga-DATA-TOC. EJNMMI Res. 2019, 9, 48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Hennrich, U.; Benešová, M. [68Ga]Ga-DOTA-TOC: The First FDA-Approved 68Ga-Radiopharmaceutical for PET Imaging. Pharmaceuticals 2020, 13, 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

| Peptide (DOTA-EMP-100) MW = 3709.7 g/mol | 50 µg (500 µL, 0.0135 µmol) | 40 µg (400 µL, 0.0108 µmol) | 30 µg (300 µL, 0.008 µmol) | 20 µg (200 µL, 0.005 µmol) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Radiochemical purity (radio-UV-HPLC) | 99.31% ± 1.8 | >99.99% | 99.73% ± 1.2 | 99.52% ± 1.3 |

| Radiochemical purity (radio-TLC) | >99.99% | >99.99% | >99.99% | >99.99% |

| pH | 7 | 7 | 7 | 7 |

| Radiochemical yield (n.d.c) | 68.17% ± 2.1 | 64.93% ± 0.5 | 64.56% ± 1.1 | 54.75% ± 1.4 |

| Volume | 10 mL | 10 mL | 10 mL | 10 mL |

| Colour | Colourless | Colourless | Colourless | Colourless |

| Molar activity | 37.42 GBq/µmol ± 2.1 | 53.08 GBq/µmol ± 0.8 | 64.63 GBq/µmol ± 1.1 | 83.80 GBq/µmol ± 1.1 |

| Test | Batch 1 | Batch 2 | Batch 3 | Acceptance Criteria |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Radiochemical purity (radio-UV-HPLC) | 99.31% | >99.99% | 99.73% | >95% |

| Radiochemical purity (radio-TLC) | >99.99% | >99.99% | >99.99% | >95% |

| pH | 7 | 7 | 7 | 4–8.5 |

| Radiochemical yield (n.d.c) | 64.37% | 64.58% | 64.56% | >40% |

| Radioactivity concentration | 75.6–52.48 | 75.6–52.77 | 75.6–52.70 | >50 MBq |

| Radioactivity | 756–524.82 | 756–527.67 | 756–527.03 | >150 MBq |

| Volume | 10 mL | 10 mL | 10 mL | 2–10 mL |

| Colour | Colourless | Colourless | Colourless | Colourless |

| Molar activity | 53.26 GBq/µmol | 53.52 GBq/µmol | 53.46 GBq/µmol | 1–60 GBq/µmol |

| Radionuclidic purity | >99.99% | >99.99% | >99.99% | 99.9% |

| 68Ge breakthrough | 0.00000036% | 0.00000033% | 0.00000035% | <0.001% |

| EtOH amount | 3.73% | 3.68% | 3.45% | <10% (v/v) (<2.5 g) |

| HEPES content | 9.45 µg/mL | 9.45 µg/mL | 9.45 µg/mL | Less than 200 µg/V of HEPES in test solution |

| Endotoxins | <17.5 IU/mL | <17.5 IU/mL | <17.5 IU/mL | <17.5 IU/mL |

| Sterility test | Sterile | Sterile | Sterile | Sterile |

| Stability over 4 h (RCP%) | >99.99% | >99.99% | >99.99% | >99.99% |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Migliari, S.; Gagliardi, A.; Guercio, A.; Scarlattei, M.; Baldari, G.; Gibson, A.; Portal, C.; Ruffini, L. Automated Scale-Down Development and Optimization of [68Ga]Ga-DOTA-EMP-100 for Non-Invasive PET Imaging and Targeted Radioligand Therapy of c-MET Overactivation in Cancer. Biologics 2025, 5, 40. https://doi.org/10.3390/biologics5040040

Migliari S, Gagliardi A, Guercio A, Scarlattei M, Baldari G, Gibson A, Portal C, Ruffini L. Automated Scale-Down Development and Optimization of [68Ga]Ga-DOTA-EMP-100 for Non-Invasive PET Imaging and Targeted Radioligand Therapy of c-MET Overactivation in Cancer. Biologics. 2025; 5(4):40. https://doi.org/10.3390/biologics5040040

Chicago/Turabian StyleMigliari, Silvia, Anna Gagliardi, Alessandra Guercio, Maura Scarlattei, Giorgio Baldari, Alex Gibson, Christophe Portal, and Livia Ruffini. 2025. "Automated Scale-Down Development and Optimization of [68Ga]Ga-DOTA-EMP-100 for Non-Invasive PET Imaging and Targeted Radioligand Therapy of c-MET Overactivation in Cancer" Biologics 5, no. 4: 40. https://doi.org/10.3390/biologics5040040

APA StyleMigliari, S., Gagliardi, A., Guercio, A., Scarlattei, M., Baldari, G., Gibson, A., Portal, C., & Ruffini, L. (2025). Automated Scale-Down Development and Optimization of [68Ga]Ga-DOTA-EMP-100 for Non-Invasive PET Imaging and Targeted Radioligand Therapy of c-MET Overactivation in Cancer. Biologics, 5(4), 40. https://doi.org/10.3390/biologics5040040