Real-World Long-Term Management of Chronic Urticaria Patients with Omalizumab: Safety, Effectiveness, and Predictive Factors for Successful Outcome

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Patients and Methods

2.1. Patient Selection and Management

2.2. Laboratory Investigations

2.3. Safety Assessment

2.4. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

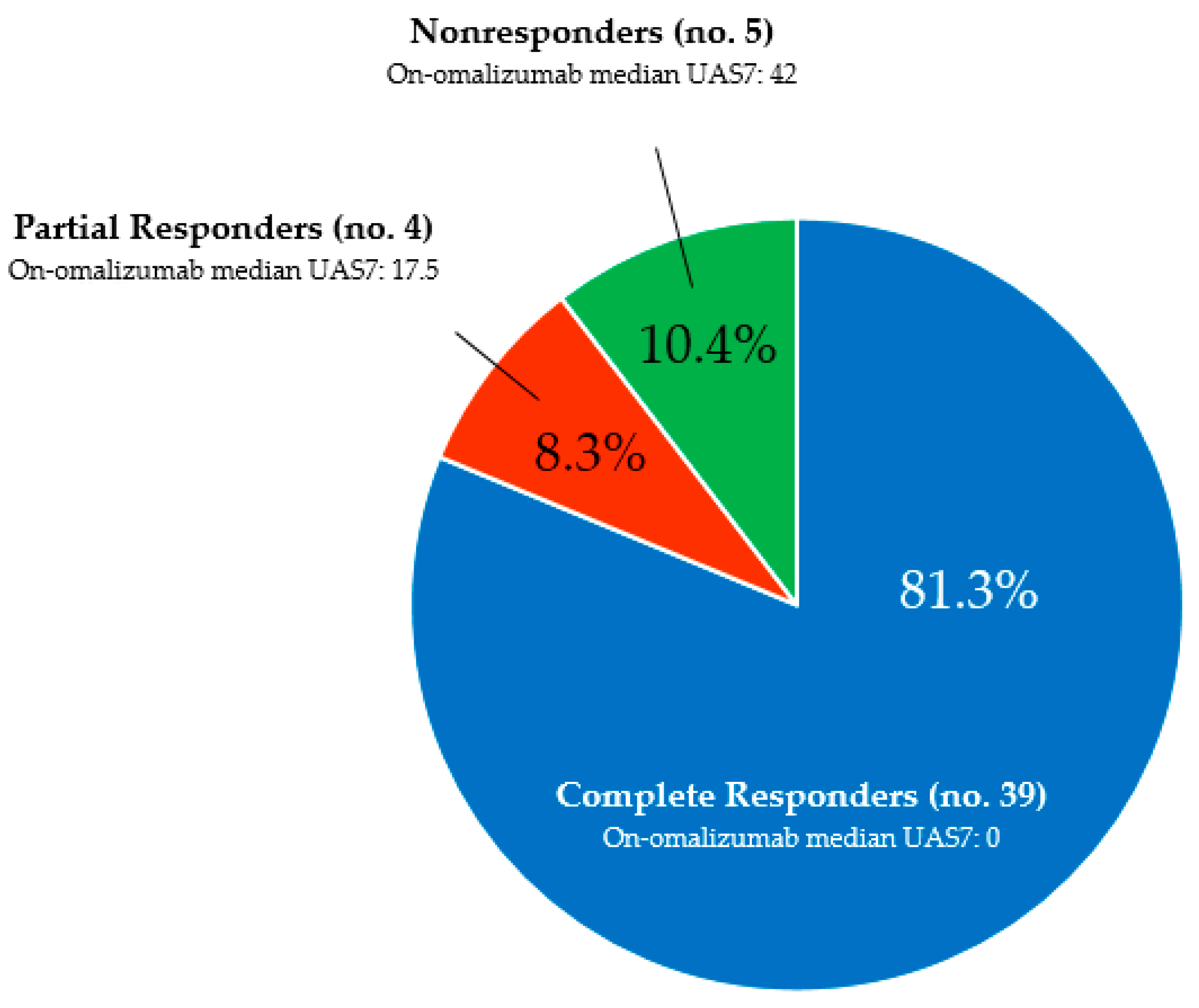

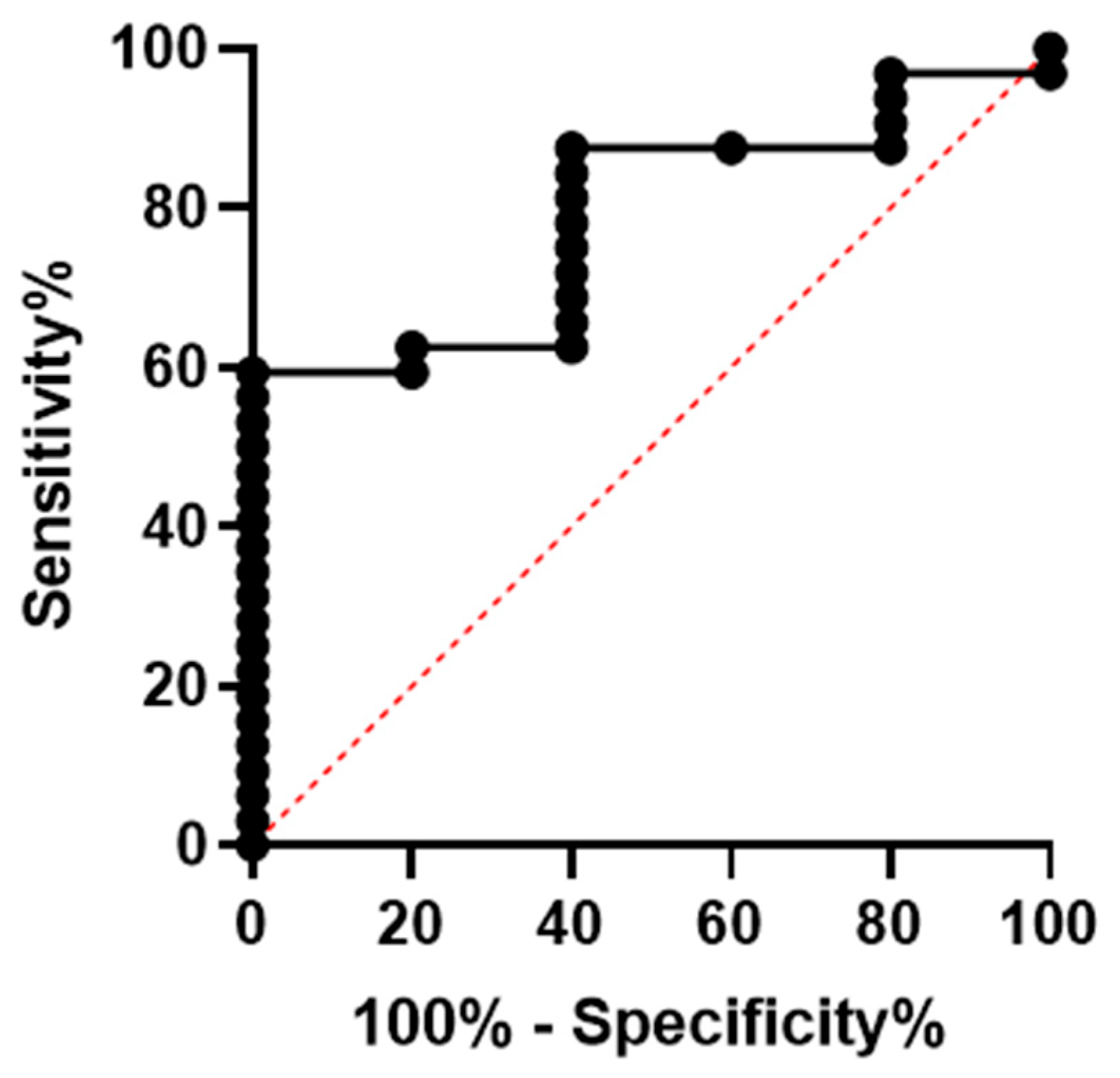

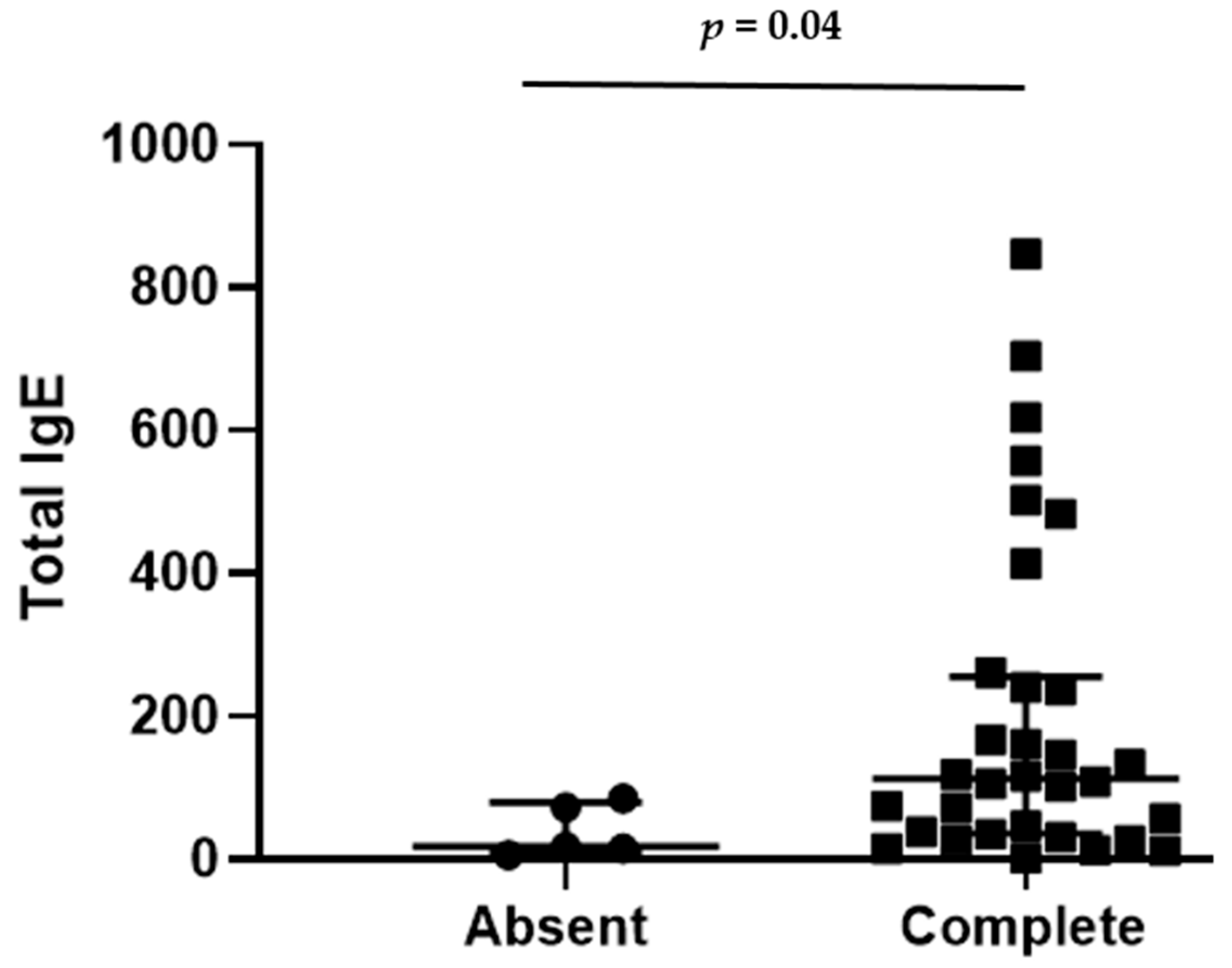

3.1. Overall Outcome

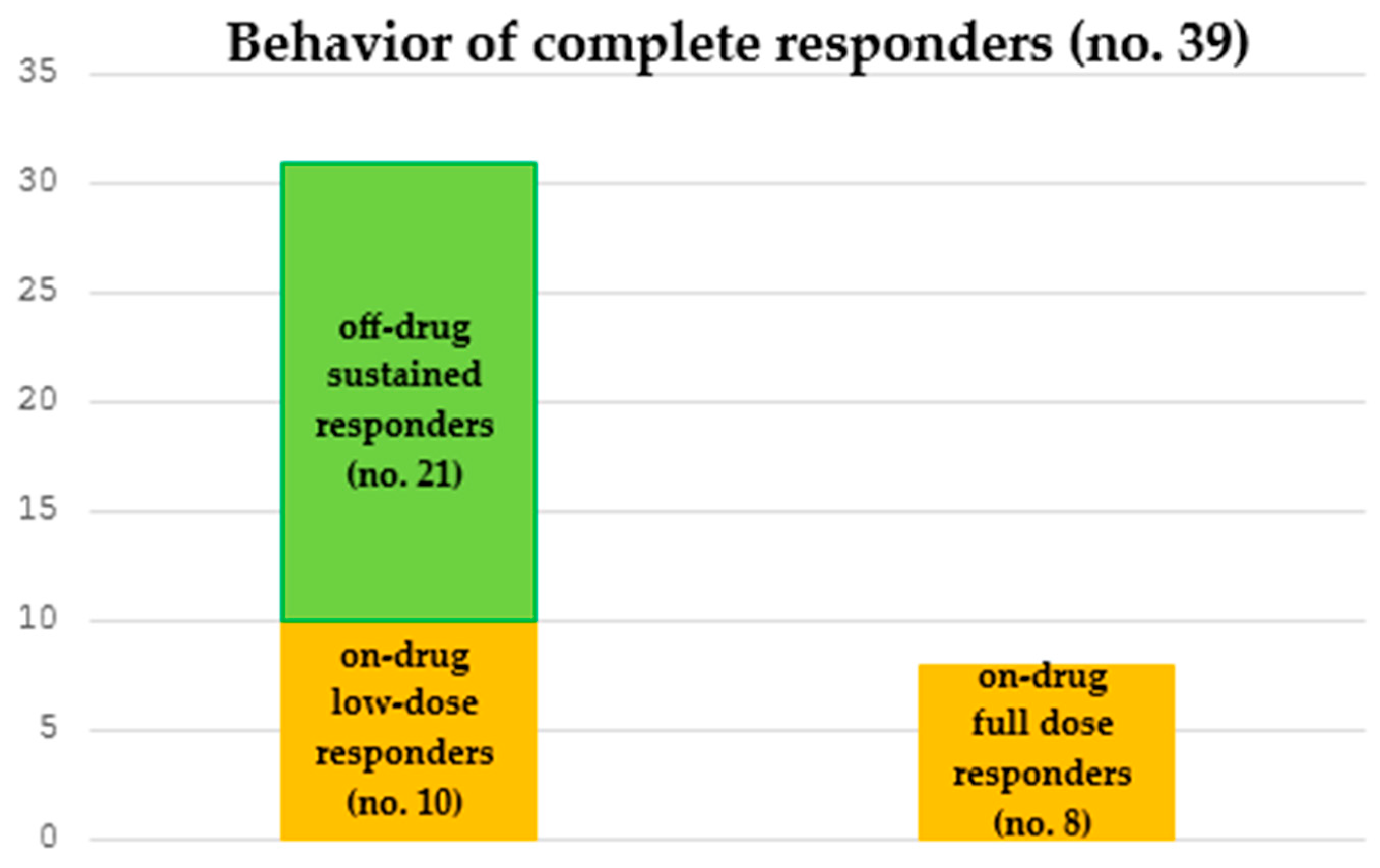

3.2. Long-Term Management of Complete Responders

3.3. Differences Between Off-Drug and On-Drug Complete Responders

3.4. Safety

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Kolkhir, P.; Bonnekoh, H.; Metz, M.; Maurer, M. Chronic spontaneous urticaria: A review. JAMA 2024, 332, 1464–1477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lang, D.M.; Sheikh, J.; Joshi, S.; Bernstein, J.A. Endotypes, phenotypes, and biomarkers in chronic spontaneous urticaria: Evolving toward personalized medicine. Ann. Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2025, 134, 408–417.e3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, R.; Bernstein, J.A. Chronic spontaneous urticaria and chronic inducible urticaria. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2025, 156, 546–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hollis, K.; Proctor, C.; McBride, D.; Balp, M.M.; McLeod, L.; Hunter, S.; Tian, H.; Khalil, S.; Maurer, M. Comparison of Urticaria Activity Score over 7 days (UAS7) values obtained from once-daily and twice-daily versions: Results from the ASSURE-CSU study. Am. J. Clin. Dermatol. 2018, 19, 267–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O’Donnell, B.F.; Lawlor, F.; Simpson, J.; Morgan, M.; Greaves, M.W. The impact of chronic urticaria on the quality of life. Br. J. Dermatol. 1997, 136, 197–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sánchez-Borges, M.; Ansotegui, I.J.; Baiardini, I.; Bernstein, J.; Canonica, G.W.; Ebisawa, M.; Gomez, M.; Gonzalez-Diaz, S.N.; Martin, B.; Morais-Almeida, M.; et al. The challenges of chronic urticaria part 1: Epidemiology, immunopathogenesis, comorbidities, quality of life, and management. World Allergy Organ J. 2021, 14, 100533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berberi, G.; Maazi, M.; Prosty, C.; McMullen, E.P.; Fein, M.; Lima, H.; Martinez-Jaramillo, E.; Ben-Shoshan, M.; Pourpanah, F.; Netchiporouk, E. Health-related quality of life in chronic urticaria: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. Pract. 2025, 13, 2317–2328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kulthanan, K.; Jiamton, S.; Thumpimukvatana, N.; Pinkaew, S. Chronic idiopathic urticaria: Prevalence and clinical course. J. Dermatol. 2007, 34, 294–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zuberbier, T.; Ensina, L.F.; Giménez-Arnau, A.; Grattan, C.; Kocatürk, E.; Kulthanan, K.; Kolkhir, P.; Maurer, M. Chronic urticaria: Unmet needs, emerging drugs, and new perspectives on personalised treatment. Lancet 2024, 404, 393–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lang, D.M. Chronic urticaria. N. Engl. J. Med. 2022, 387, 824–831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asero, R.; Calzari, P.; Vaienti, S.; Cugno, M. Therapies for chronic spontaneous urticaria: Present and future developments. Pharmaceuticals 2024, 17, 1499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yosipovitch, G.; Biazus Soares, G.; Mahmoud, O. Current and emerging therapies for chronic spontaneous urticaria: A narrative review. Dermatol. Ther. 2023, 13, 1647–1660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolkhir, P.; Fok, J.S.; Kocatürk, E.; Li, P.H.; Okas, T.L.; Marcelino, J.; Metz, M. Update on the treatment of chronic spontaneous urticaria. Drugs 2025, 85, 475–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaplan, A.P. Chronic spontaneous urticaria: Pathogenesis and treatment considerations. Allergy Asthma Immunol. Res. 2017, 9, 477–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chang, T.W.; Wu, P.C.; Hsu, C.L.; Hung, A.F. Anti-IgE antibodies for the treatment of IgE-mediated allergic diseases. Adv. Immunol. 2007, 93, 63–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Humbert, M.; Beasley, R.; Ayres, J.; Slavin, R.; Hébert, J.; Bousquet, J.; Beeh, K.M.; Ramos, S.; Canonica, G.W.; Hedgecock, S.; et al. Benefits of omalizumab as add-on therapy in patients with severe persistent asthma who are inadequately controlled despite best available therapy (GINA 2002 step 4 treatment): INNOVATE. Allergy 2005, 60, 309–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Agache, I.; Rocha, C.; Beltran, J.; Song, Y.; Posso, M.; Solà, I.; Alonso-Coello, P.; Akdis, C.; Akdis, M.; Canonica, G.W.; et al. Efficacy and safety of treatment with biologicals (benralizumab, dupilumab and omalizumab) for severe allergic asthma: A systematic review for the EAACI Guidelines—recommendations on the use of biologicals in severe asthma. Allergy 2020, 75, 1043–1057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spector, S.L.; Tan, R.A. Effect of omalizumab in patients with chronic urticaria. Ann. Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2007, 99, 190–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spector, S.L.; Tan, R.A. Advances in allergic skin disease: Omalizumab is a promising therapy for urticaria and angioedema. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2009, 123, 273–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaplan, A.P.; Joseph, K.; Maykut, R.J.; Geba, G.P.; Zeldin, R.K. Treatment of chronic autoimmune urticaria with omalizumab. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2008, 122, 569–573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romano, C.; Sellitto, A.; De Fanis, U.; Esposito, G.; Arbo, P.; Giunta, R.; Lucivero, G. Maintenance of remission with low-dose omalizumab in long-lasting, refractory chronic urticaria. Ann. Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2010, 104, 95–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saini, S.; Rosen, K.E.; Hsieh, H.J.; Wong, D.A.; Conner, E.; Kaplan, A.; Spector, S.; Maurer, M. A randomized, placebo-controlled, dose-ranging study of single-dose omalizumab in patients with H1-antihistamine-refractory chronic idiopathic urticaria. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2011, 128, 567–573.e1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maurer, M.; Rosén, K.; Hsieh, H.J.; Saini, S.; Grattan, C.; Gimenéz-Arnau, A.; Agarwal, S.; Doyle, R.; Canvin, J.; Kaplan, A.; et al. Omalizumab for the treatment of chronic idiopathic or spontaneous urticaria. N. Engl. J. Med. 2013, 368, 924–935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saini, S.S.; Bindslev-Jensen, C.; Maurer, M.; Grob, J.J.; Bülbül Baskan, E.; Bradley, M.S.; Canvin, J.; Rahmaoui, A.; Georgiou, P.; Alpan, O.; et al. Efficacy and safety of omalizumab in patients with chronic idiopathic/spontaneous urticaria who remain symptomatic on H1 antihistamines: A randomized, placebo-controlled study. J. Investig. Dermatol. 2015, 135, 67–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCormack, P.L. Omalizumab: A review of its use in patients with chronic spontaneous urticaria. Drugs 2014, 74, 1693–1699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Akdaş, E.; Adışen, E.; Öztaş, M.O.; Aksakal, A.B.; İlter, N.; Gülekon, A. Real-life clinical practice with omalizumab in 134 patients with refractory chronic spontaneous urticaria: A single-center experience. An. Bras. Dermatol. 2023, 98, 240–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Calzari, P.; Chiei Gallo, A.; Barei, F.; Bono, E.; Cugno, M.; Marzano, A.V.; Ferrucci, S.M. Omalizumab for the treatment of chronic spontaneous urticaria in adults and adolescents: An eight-year real-life experience. J. Clin. Med. 2024, 13, 5610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seetasith, A.; Holden, M.; Hetherington, J.; Keal, A.; Salmon, P.; Bernstein, J.A.; Casale, T.B. Real-world outcomes in patients with chronic spontaneous urticaria receiving omalizumab: Insights from a clinical practice survey. Curr. Med. Res. Opin. 2024, 40, 1059–1066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Terhorst-Molawi, D.; Fox, L.; Siebenhaar, F.; Metz, M.; Maurer, M. Stepping down treatment in chronic spontaneous urticaria: What we know and what we don’t know. Am. J. Clin. Dermatol. 2023, 24, 397–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brás, R.; Costa, C.; Limão, R.; Caldeira, L.E.; Paulino, M.; Pedro, E. Omalizumab in chronic spontaneous urticaria (CSU): Real-life experience in dose/interval adjustments and treatment discontinuation. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. Pract. 2023, 11, 2392–2402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batyrbayeva, A.; Ispayeva, Z.; Pashimov, M.; Kaibullayeva, J.; Baidildayeva, M.; Kapalbekova, U.; Tokmurzayeva, E.; Plakhotina, O.; Maldybayeva, A.; Salmanova, A.; et al. Clinical phenotypes and biomarkers in chronic urticaria. Clin. Chim. Acta 2025, 571, 120233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Romano, C.; Sellitto, A.; De Fanis, U.; Balestrieri, A.; Savoia, A.; Abbadessa, S.; Astarita, C.; Lucivero, G. Omalizumab for difficult-to-treat dermatological conditions: Clinical and immunological features from a retrospective real-life experience. Clin. Drug Investig. 2015, 35, 159–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dong, C.H.; Wang, Z.M.; Chen, S.Y. Neutrophil to lymphocyte ratio predict mortality and major adverse cardiac events in acute coronary syndrome: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin. Biochem. 2018, 52, 131–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carrión-Barberà, I.; Lood, C. Performance of the neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio as a prognostic tool for survival in solid cancers. Front. Oncol. 2025, 15, 1616477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiaoyan, L.; Zhongying, B.; Shuhong, D.; Jing, S.; Yijie, Z.; Jie, Z.; Jingxin, L. Predictive model for coronavirus disease 2019 severity based on blood biomarkers: A retrospective study. Front. Med. 2025, 8, 1597082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aitella, E.; Romano, C.; Ginaldi, L.; Cozzolino, D. Mast cells at the crossroads of hypersensitivity reactions and neurogenic inflammation. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, W.; Xia, J.; Zeng, Q. Levels of serum inflammatory cytokines and their correlations with disease severity in patients with chronic spontaneous urticaria. Postepy Dermatol. Alergol. 2024, 41, 85–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trotta, M.C.; Alfano, R.; Cuomo, G.; Romano, C.; Gravina, A.G.; Romano, M.; Galdiero, M.; Montemurro, M.V.; Giordano, A.; D’Amico, M. Comparison of timing to develop anti-drug antibodies to infliximab and adalimumab between adult and pediatric age groups, males and females. J. Pediatr. Pharmacol. Ther. 2022, 27, 63–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corren, J.; Casale, T.B.; Lanier, B.; Buhl, R.; Holgate, S.; Jimenez, P. Safety and tolerability of omalizumab. Clin. Exp. Allergy 2009, 39, 788–797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohta, K.; Yamamoto, M.; Sato, N.; Ikeda, K.; Miyamoto, T. One year treatment with omalizumab is effective and well tolerated in Japanese patients with moderate-to-severe persistent asthma. Allergol. Int. 2010, 59, 167–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pongdee, T.; Li, J.T. Omalizumab safety concerns. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2025, 155, 31–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Romano, C.; Cozzolino, D.; Corona, M.E.; Aitella, E. Efficacy and safety of dupilumab across different Th2-type-mediated diseases: A real-life preliminary experience. Biologics 2025, 5, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romano, C. Safety and effectiveness of dupilumab in prurigo nodularis. J. Investig. Allergol. Clin. Immunol. 2021, 31, 162–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Whole Patient Population, No. 48 | |

|---|---|

| Gender, M/F | 11/37 |

| Age (yrs), mean ± sd/median | 43.3 ± 13.5/43.5 |

| CU duration (months), mean ± sd/median | 29.1 ± 54.3/7.5 |

| Total serum IgE (IU/mL), mean ± sd/median | 189.5 ± 217/107.8 |

| Concomitant atopy, % | 38.6 |

| Concomitant autoimmune diseases *, % | 34.1 |

| Circulating eosinophil counts (cells/μL), mean ± sd/median | 166.9 ± 104.1/140 |

| Circulating basophil counts (cells/μL), mean ± sd/median | 35.3 ± 54.7/20 |

| NLR, mean ± sd/median | 2.2 ± 0.9/2 |

| Response to omalizumab, no. | 39 CR, 4 PR, 5 NR |

| Pre-omalizumab UAS7, mean ± sd/median | 37.9 ± 6.4/42 |

| Time to response to omalizumab (days), mean ± sd/median | 15.3 ± 25.1/5 |

| Treatment duration (months), mean ± sd/median | 32.5 ± 38.4/17.5 |

| Complete Responders (No. 39) | Nonresponders (No. 5) | p | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 44 (35–53) | 33 (32–72) | 0.90 |

| Sex (F, %) | 74.4 | 80 | 0.99 |

| Atopy (%) | 42.9 | 0 | 0.14 |

| Autoimmunity (%) | 28.7 | 60.0 | 0.31 |

| NLR | 1.88 (1.43–2.69) | 2.44 (1.24–3.69) | 0.88 |

| Basophils (cells/μL) | 20 (10–40) | 11 (10–30) | 0.71 |

| Eosinophils (cells/μL) | 130 (100–200) | 160 (158–170) | 0.49 |

| Total IgE (IU/mL) | 112.5 (37.2–250.5) | 18 (15.8–73.1) | 0.04 |

| Pre-omalizumab UAS7 | 42 (28–42) | 42 (42–42) | 0.13 |

| On omalizumab UAS7 | 0 (0–0) | 42 (42–42) | <0.0001 |

| CU duration (months) | 8 (4–12) | 5 (4–26) | 0.68 |

| Treatment duration (months) | 25 (8–52) | 6 (4–12) | 0.02 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Romano, C.; Cozzolino, D.; Umano, G.R.; Aitella, E. Real-World Long-Term Management of Chronic Urticaria Patients with Omalizumab: Safety, Effectiveness, and Predictive Factors for Successful Outcome. Biologics 2025, 5, 33. https://doi.org/10.3390/biologics5040033

Romano C, Cozzolino D, Umano GR, Aitella E. Real-World Long-Term Management of Chronic Urticaria Patients with Omalizumab: Safety, Effectiveness, and Predictive Factors for Successful Outcome. Biologics. 2025; 5(4):33. https://doi.org/10.3390/biologics5040033

Chicago/Turabian StyleRomano, Ciro, Domenico Cozzolino, Giuseppina Rosaria Umano, and Ernesto Aitella. 2025. "Real-World Long-Term Management of Chronic Urticaria Patients with Omalizumab: Safety, Effectiveness, and Predictive Factors for Successful Outcome" Biologics 5, no. 4: 33. https://doi.org/10.3390/biologics5040033

APA StyleRomano, C., Cozzolino, D., Umano, G. R., & Aitella, E. (2025). Real-World Long-Term Management of Chronic Urticaria Patients with Omalizumab: Safety, Effectiveness, and Predictive Factors for Successful Outcome. Biologics, 5(4), 33. https://doi.org/10.3390/biologics5040033