Primary Cutaneous Cribriform Apocrine Carcinoma: A Case Report and Narrative Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

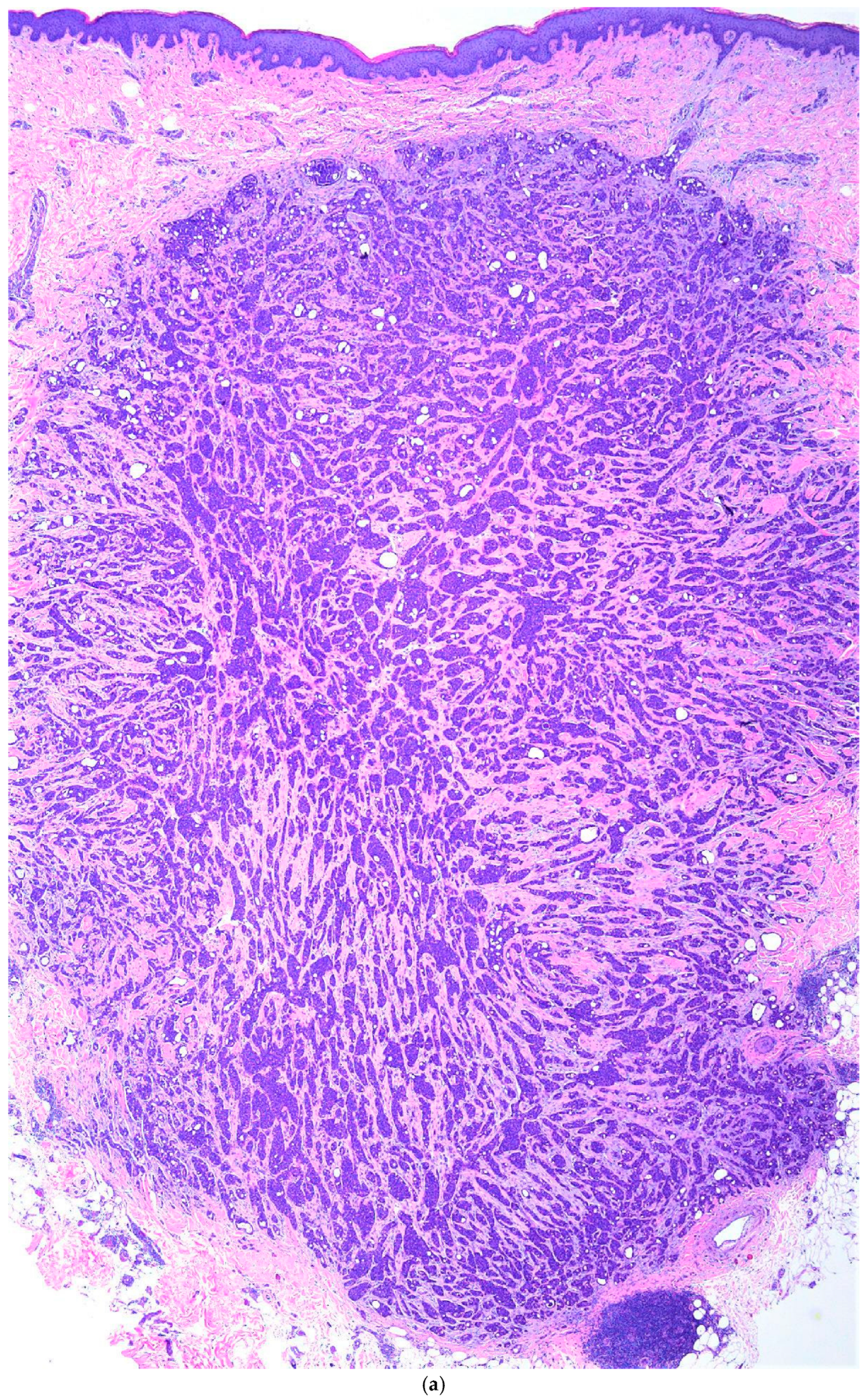

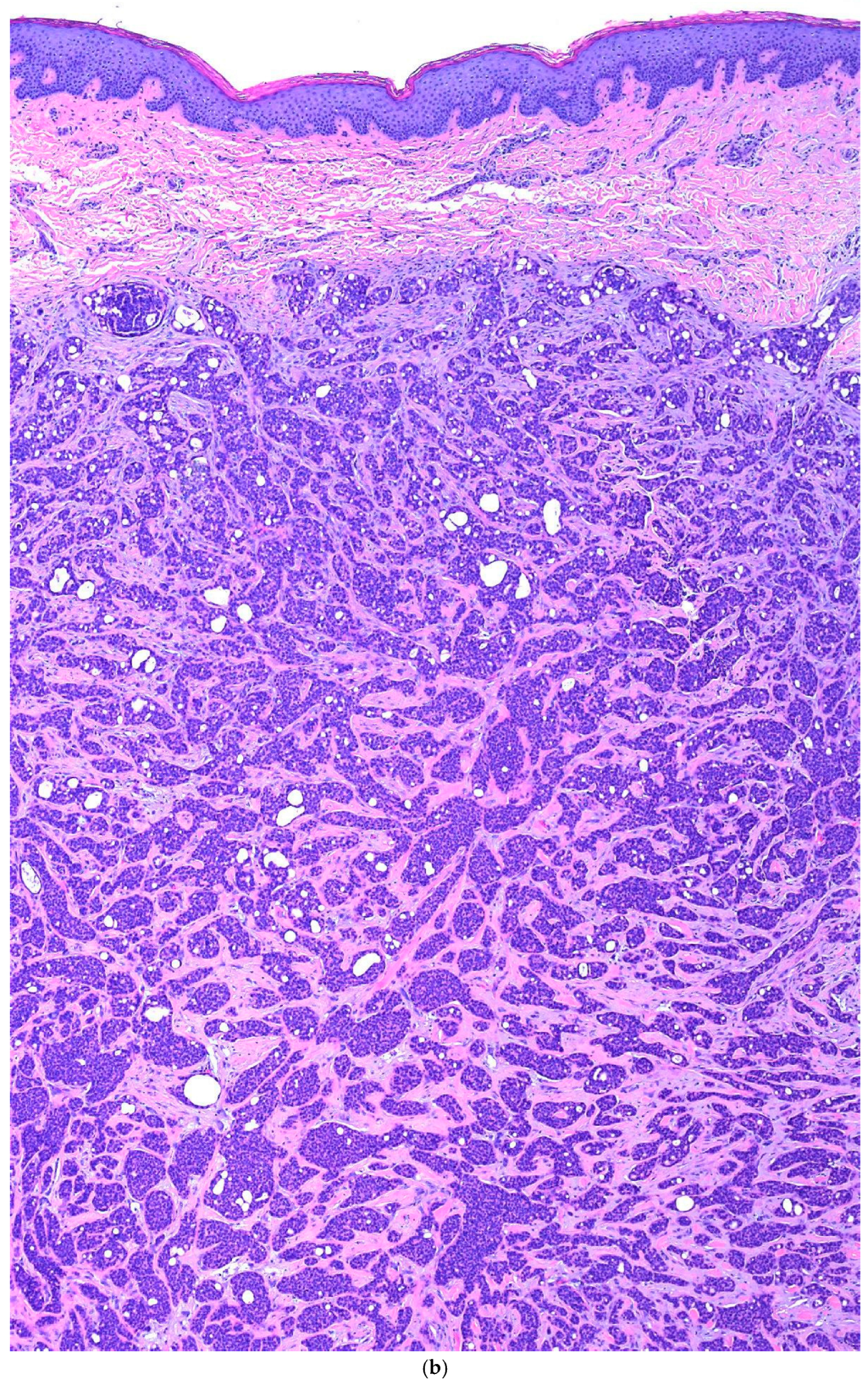

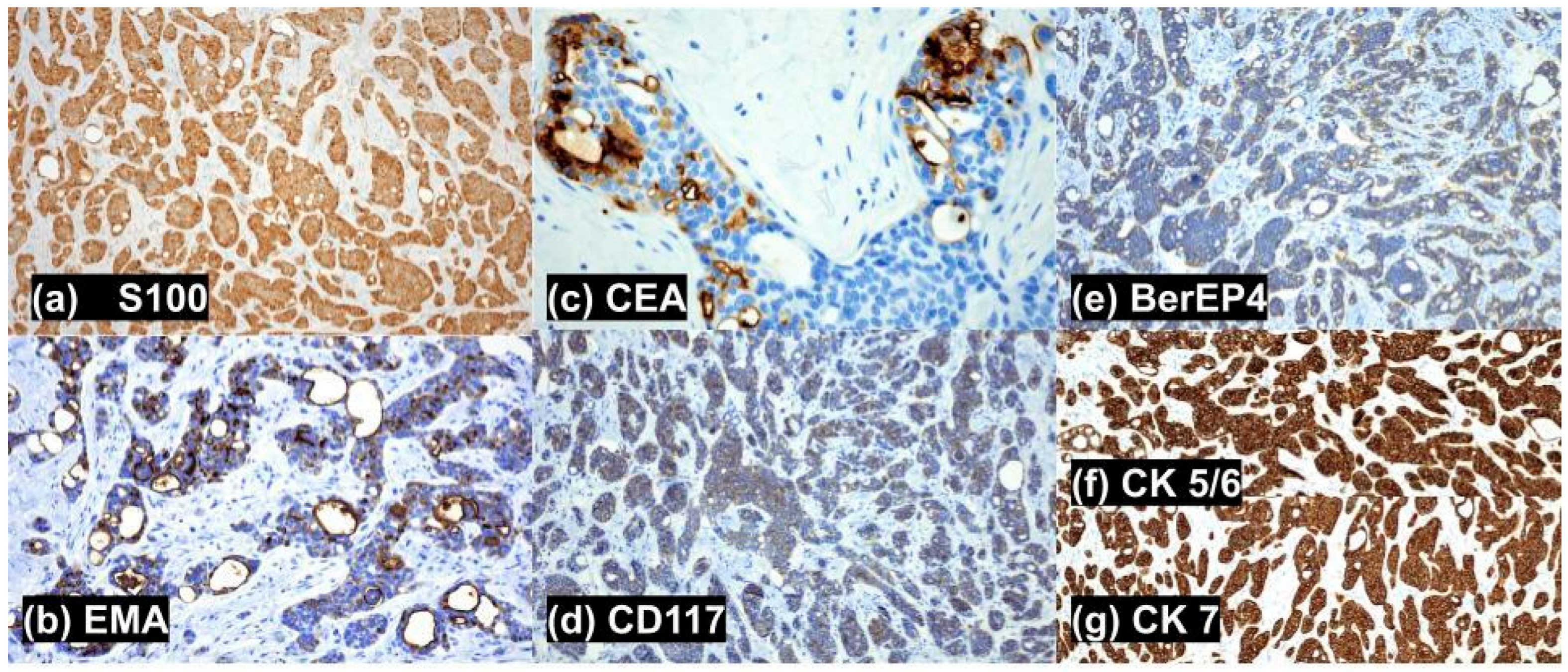

3. Case

4. Search Methods

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

7. Limitations

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Arps, D.P.; Chan, M.P.; Patel, R.M.; Andea, A.A. Primary cutaneous cribriform carcinoma: Report of six cases with clinicopathologic data and immunohistochemical profile. J. Cutan. Pathol. 2015, 42, 379–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, A.; Khachemoune, A. Reappraisal and literature review of primary cutaneous cribriform apocrine carcinoma. Arch. Dermatol. Res. 2023, 315, 7–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, H.; Won, C.H.; Park, C.S. A case of cribriform carcinoma of the skin: A newly described rare condition. J. Pathol. Transl. Med. 2021, 55, 68–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J. A Case of Primary Cutaneous Cribriform Carcinoma on the Back. Clin. Dermatol. Res. J. 2019, 58, 846–848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandez-Flores, A.; Pol, A.; Juanes, F.; Crespo, L.G. Immunohistochemical phenotype of cutaneous cribriform carcinoma with a panel of 15 antibodies. Med. Mol. Morphol. 2007, 40, 212–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moritani, S.; Ichihara, S.; Hasegawa, M.; Endo, T.; Oiwa, M.; Shiraiwa, M.; Nishida, C.; Morita, T.; Sato, Y.; Hayashi, T.; et al. Intracytoplasmic Lipid Accumulation in Apocrine Carcinoma of the Breast Evaluated with Adipophilin Immunoreactivity: A Possible Link Between Apocrine Carcinoma and Lipid-rich Carcinoma. Am. J. Surg. Pathol. 2011, 35, 861–867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cardoso, J.; Calonje, E. Malignant Sweat Gland tumours: An update. Histopathology 2015, 67, 589–606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wick, M.R.; Ockner, D.M.; Mills, S.E.; Ritter, J.H.; Swanson, P.E. Homologous carcinomas of the breasts, skin, and salivary glands. A histologic and immunohistochemical comparison of ductal mammary carcinoma, ductal sweat gland carcinoma, and salivary duct carcinoma. Am. J. Clin. Pathol. 1998, 109, 75–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boettler, M.; Hickmann, M.A.; Travers, J.B. Primary Cutaneous Cribriform Apocrine Carcinoma. Am. J. Case Rep. 2021, 22, e927744-1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rütten, A.; Hegenbarth, W.; Kohl, P.K.; Hillen, U.; Redler, S. Primary cutaneous adenoid cystic carcinoma mimicking dermal cylindroma: Histology of the complete surgical excision as the key to diagnosis. J. Dtsch. Dermatol. Ges. 2018, 16, 1016–1018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramakrishnan, R.; Chaudhry, I.H.; Ramdial, P.; Lazar, A.J.; McMenamin, M.E.; Kazakov, D.; Brenn, T.; Calonje, E. Primary cutaneous adenoid cystic carcinoma: A clinicopathologic and immunohistochemical study of 27 cases. Am. J. Surg. Pathol. 2013, 37, 1603–1611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macagno, N.; Sohier, P.; Kervarrec, T.; Pissaloux, D.; Jullie, M.L.; Cribier, B.; Battistella, M. Recent Advances on Immunohistochemistry and Molecular Biology for the Diagnosis of Adnexal Sweat Gland Tumors. Cancers 2022, 14, 476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oualla, K.; Acharfi, N.; Benbrahim, Z.; Arifi, S.; Bouhafa, T.; Hassouni, K.; Mellas, N. Primary Cutaneous Adenoid-Cystic Carcinoma: A Case Report and Literature Review. Int. J. Case Rep. Ther. Stud. 2019, 1, 08. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rollins-Raval, M.; Chivukula, M.; Tseng, G.C.; Jukic, D.; Dabbs, D.J. An Immunohistochemical Panel to Differentiate Metastatic Breast Carcinoma to Skin from Primary Sweat Gland Carcinomas with a Review of the Literature. Arch. Pathol. Lab. Med. 2011, 135, 975–983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moore, R.F.; Cuda, J.D. Secretory carcinoma of the skin: Case report and review of the literature. JAAD Case Rep. 2017, 3, 559–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mertens, R.B.; de Peralta-Venturina, M.N.; Balzer, B.L.; Frishberg, D.P. GATA3 Expression in Normal Skin and in Benign and Malignant Epidermal and Cutaneous Adnexal Neoplasms. Am. J. Dermatopathol. 2015, 37, 885–891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martins, M.A.; Moreira, C.A.; Queiroz, M.D.C.G.A.A.; Martins, W.H.; Pereira, G.V.; Abreu, L.C.D. Malignant adnexal cutaneous tumor of the scalp: A case report of difficult differential diagnosis between metastatic breast cancer and primary sweat gland tumor. J. Hum. Growth Dev. 2021, 31, 177–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mariano, F.V.; dos Santos, H.T.; Azañero, W.D.; da Cunha, I.W.; Coutinho-Camilo, C.M.; de Almeida, O.P.; Kowalski, L.P.; Altemani, A. Mammary analogue secretory carcinoma of salivary glands is a lipid-rich tumour, and adipophilin can be valuable in its identification. Histopathology 2013, 63, 558–567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amin, S.M.; Beattie, A.; Ling, X.; Jennings, L.J.; Guitart, J. Primary Cutaneous Mammary Analog Secretory Carcinoma with ETV6-NTRK3 Translocation. Am. J. Dermatopathol. 2016, 38, 842–845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Javaheripour, A.; Saatloo, M.V.; Vahed, N.; Gavgani, L.F.; Kouhsoltani, M. Evaluation of HER2/neu expression in different types of salivary gland tumors: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Med. Life 2022, 15, 595–600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Griffith, M.; Singh, R.; Alabkaa, A.; Reddy, V.; Ahmed, A. Primary cutaneous apocrine carcinoma, arising in tubular apocrine adenoma. J. Cutan. Pathol. 2023, 50, 1042–1047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petersson, F.; Lian, D.; Chau, Y.P.; Yan, B. Mammary analogue secretory carcinoma: The first submandibular case reported including findings on fine needle aspiration cytology. Head Neck Pathol. 2012, 6, 135–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Llamas-Velasco, M.; Mentzel, T.; Rütten, A. Primary cutaneous secretory carcinoma: A previously overlooked low-grade sweat gland carcinoma. J. Cutan. Pathol. 2018, 45, 240–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eiger-Moscovich, M.; Zhang, P.J.L.; Lally, S.E.; Shields, C.L.; Eagle, R.C., Jr.; Milman, T. Tubular apocrine adenoma of the eyelid—A case report and literature review. Saudi J. Ophthalmol. Off. J. Saudi Ophthalmol. Soc. 2019, 33, 304–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aldrees, S.S.; Zoroquiain, P.; Alghamdi, S.A.; Logan, P.; Kavalec, C.; Burnier, M. Apocrine adenocarcinoma of the eyelid. Int. J. Ophthalmol. 2016, 9, 1086–1088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Requena, L.; Sangüeza, O. Secretory Carcinoma of the Skin. In Cutaneous Adnexal Neoplasms; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mark, J.; Mentrikoski, M.D.; Mark, R.; Wick, M.D. Immunohistochemical Distinction of Primary Sweat Gland Carcinoma and Metastatic Breast Carcinoma: Can It Always Be Accomplished Reliably? Am. J. Clin. Pathol. 2015, 143, 430–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, K.; Patwa, H.S.; Niehaus, A.G.; Filho, G.O.F.; Lack, C.M. Mammary analogue secretory carcinoma presenting as a cystic parotid mass. Radiol. Case Rep. 2019, 14, 1103–1108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alvarado, D.A.; Aristimuño, T.M.; Esquivel, P.I.A.; Arenas, R. Apocrine tubular adenoma. Report a case. Cosmet. Med. Surg. Dermatol. 2023, 21, 311–313. [Google Scholar]

- Terada, T. Adenoid cystic carcinoma of the oral cavity: Immunohistochemical study of four cases. Int. J. Clin. Exp. Pathol. 2013, 6, 932–938. [Google Scholar]

- Cacchi, C.; Persechino, S.; Fidanza, L.; Bartolazzi, A. A primary cutaneous adenoid-cystic carcinoma in a young woman. Differential diagnosis and clinical implications. Rare Tumors 2011, 3, e3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Choi, J.; Seo, J.H.; Choi, J.Y.; Seo, B.F.; Kwon, H.; Jung, S.N. Apocrine tubular adenoma on the palm: A case report. Medicine 2021, 100, e28002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- El Demellawy, D.; Daya, D.; Alowami, S. Vulvar apocrine tubular adenoma: An unusual location. Int. J. Gynecol. Pathol. Off. J. Int. Soc. Gynecol. Pathol. 2008, 27, 301–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, S.J.; Chung, K.Y.; Kwon, J.E.; Yoon, S.O.; Kim, S.K. Expression of EpCAM in adenoid cystic carcinoma. Pathology 2018, 50, 737–741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Coban, D.T.; Erol, M.K.; Suren, D.; Tutus, B. Primary cutaneous adenoid cystic carcinoma of the eyelid and literature review. Arq. Bras. Oftalmol. 2015, 78, 323–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tiwari, R.; Agarwal, S.; Sharma, M.; Gaba, S. Primary cutaneous adenoid cystic carcinoma: A clinical and histopathological mimic: A case report. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. Cases 2018, 4, 175–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrera, J.E.; Shroyer, K.R.; Said, S.; Hoernig, G.; Melrose, R.; Freedman, P.D.; Wright, T.A.; Greer, R.O. Estrogen and progesterone receptor and p53 gene expression in adenoid cystic cancer. Head Neck Pathol. 2008, 2, 13–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Stain | Cutaneous Apocrine Cribriform Carcinoma (PCCAC) | Metastatic Breast Carcinoma, Invasive Ductal Type (MMDAC) | Cutaneous Secretory Carcinoma (PCSC) | Cutaneous Adenoid Cystic Carcinoma (PCACC) | Tubular Apocrine Adenoma (TA) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GATA 3 | negative | positive | positive | positive | Positive |

| Adipophilin | negative | Mostly positive | positive | positive | Negative |

| HER2/neu | negative | Mostly positive | negative | variable | Negative |

| CD117 | Mostly positive | negative | positive | positive | Positive |

| p63 | variable | negative | variable | Positive | Positive |

| D240 | positive | negative | positive | positive | Positive |

| SMA | negative | negative | Mostly negative | Mostly positive | Positive |

| CK 7 | Mostly positive | Mostly negative | positive | Mostly positive | positive |

| CK 5/6 | positive | Mostly negative | positive | positive | positive |

| S100 | variable | variable | positive | Mostly positive | Mostly positive |

| EMA | positive | N/A | Mostly positive | positive | positive |

| GCDFP-15 | negative | Mostly positive | Mostly positive | negative | Mostly positive |

| CEA | positive | Mostly negative | Negative | Mostly positive | positive |

| ER+ | variable | variable | negative | variable | positive |

| PR+ | variable | variable | negative | Mostly negative | negative |

| AE1/AE3 | Mostly positive | N/A | positive | positive | positive |

| CAM5.2 | Mostly positive | N/A | Mostly positive | positive | positive |

| calciponin | Variable | N/A | Mostly positive | positive | positive |

| mammaglobin | positive | Mostly positive | positive | positive | positive |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Okereke, R.; Linfante, A. Primary Cutaneous Cribriform Apocrine Carcinoma: A Case Report and Narrative Review. BioMed 2025, 5, 26. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomed5040026

Okereke R, Linfante A. Primary Cutaneous Cribriform Apocrine Carcinoma: A Case Report and Narrative Review. BioMed. 2025; 5(4):26. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomed5040026

Chicago/Turabian StyleOkereke, Robyn, and Anthony Linfante. 2025. "Primary Cutaneous Cribriform Apocrine Carcinoma: A Case Report and Narrative Review" BioMed 5, no. 4: 26. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomed5040026

APA StyleOkereke, R., & Linfante, A. (2025). Primary Cutaneous Cribriform Apocrine Carcinoma: A Case Report and Narrative Review. BioMed, 5(4), 26. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomed5040026