Perspectives on Light-Based Disinfection to Reduce the Risk of COVID-19 Transmission during Dental Care

Abstract

:1. Introduction

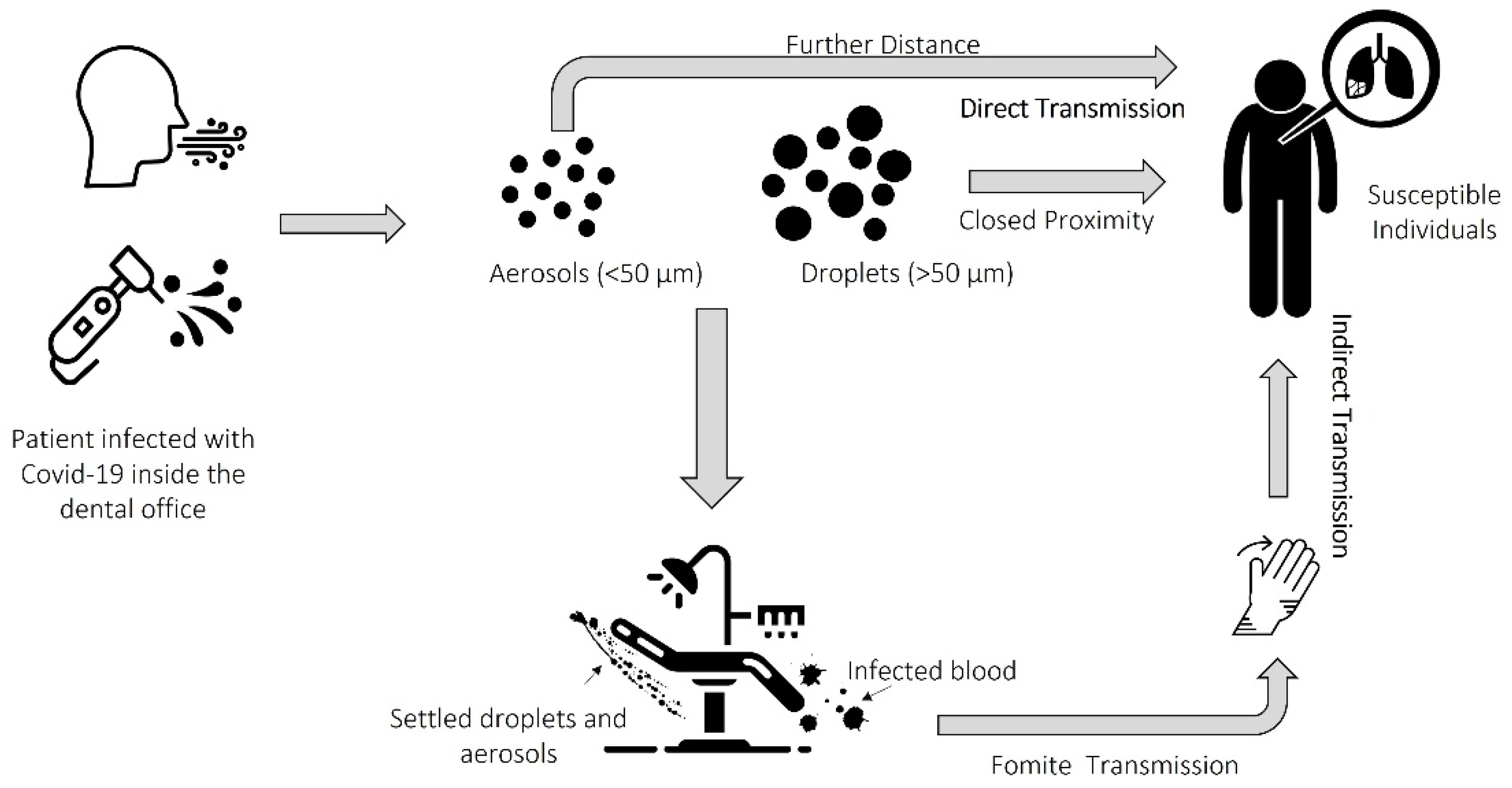

2. SARS-CoV-2 Transmission in Dental Settings

3. Infection Control in Dental Settings

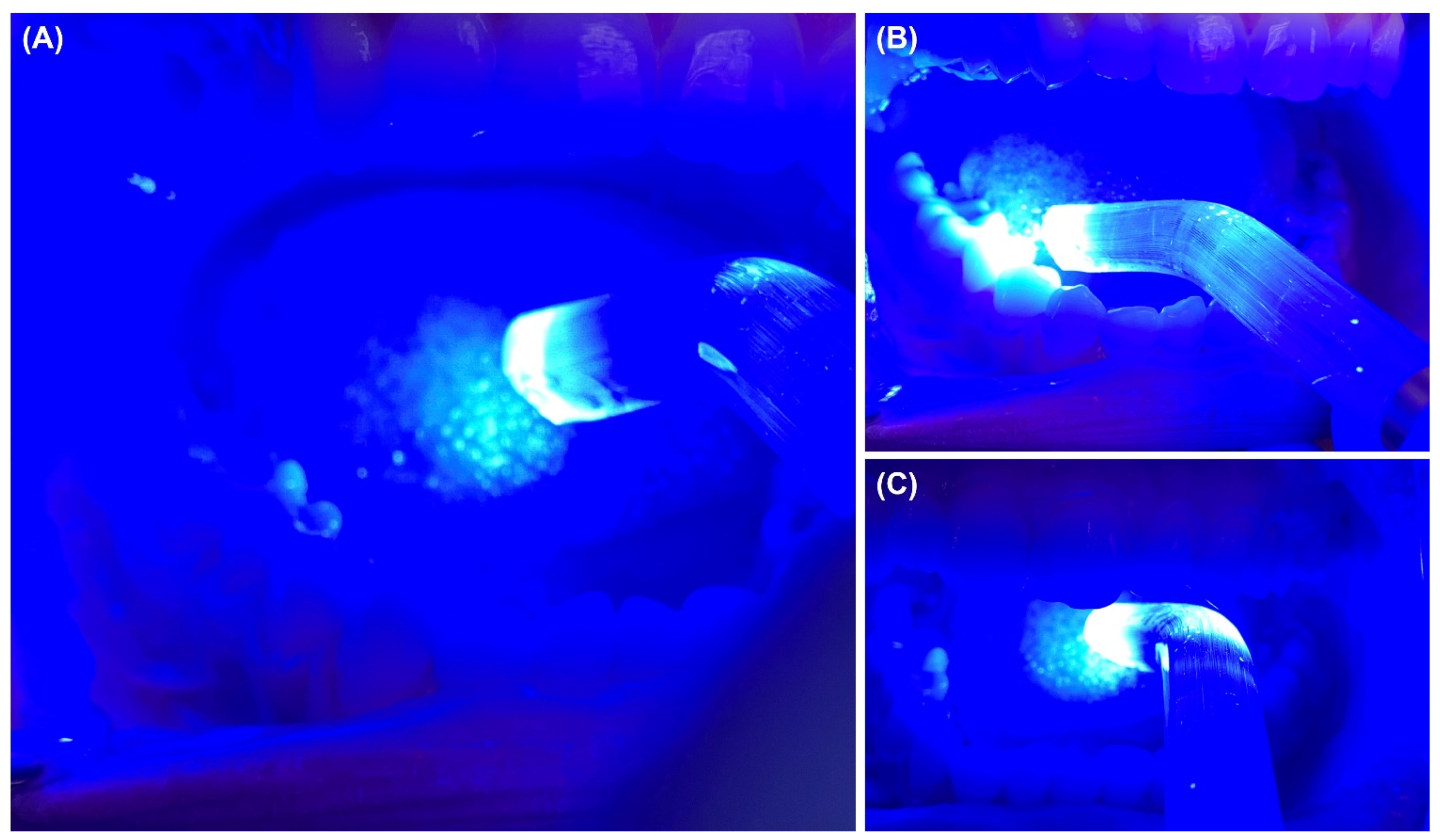

4. Preprocedural Disinfection to Prevent the Spreading of SARS-CoV-2

5. Current Trends in Light-Based Oral Disinfection

- The most frequently used photosensitizer to disinfect the oral cavity is curcumin at the following concentrations: 25 mg/L; 30 mg/L; 100 mg/L; 1 g/L, and 1.5 g/L.

- Typical doses of energy used include 20.1 J/cm2, 85 J/cm2, 100 J/cm2 and 200 J/cm2.

- Concentration-dependent mechanism (higher concentration = higher reductions).

- High curcumin concentrations were found to exert long-term (24 h) effects.

- Future studies should consider different photosensitizers and energy doses.

- aPDT disinfection approaches cited should be investigated against SARS-CoV-2.

6. Perspective and Future Outlook

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Zhu, H.; Wei, L.; Niu, P. The Novel Coronavirus Outbreak in Wuhan, China. Glob. Health Res. Policy 2020, 5, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Song, F.; Shi, N.; Shan, F.; Zhang, Z.; Shen, J.; Lu, H.; Ling, Y.; Jiang, Y.; Shi, Y. Emerging 2019 Novel Coronavirus (2019-NCoV) Pneumonia. Radiology 2020, 295, 210–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Backer, J.A.; Klinkenberg, D.; Wallinga, J. Incubation Period of 2019 Novel Coronavirus (2019-NCoV) Infections among Travellers from Wuhan, China, 20-28 January 2020. Eurosurveillance 2020, 25, 2000062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Li, Q.; Guan, X.; Wu, P.; Wang, X.; Zhou, L.; Tong, Y.; Ren, R.; Leung, K.S.M.; Lau, E.H.Y.; Wong, J.Y.; et al. Early Transmission Dynamics in Wuhan, China, of Novel Coronavirus-Infected Pneumonia. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020, 382, 1199–1207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sohrabi, C.; Alsafi, Z.; O’Neill, N.; Khan, M.; Kerwan, A.; Al-Jabir, A.; Iosifidis, C.; Agha, R. World Health Organization Declares Global Emergency: A Review of the 2019 Novel Coronavirus (COVID-19). Int. J. Surg. 2020, 76, 71–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaim, S.; Chong, J.H.; Sankaranarayanan, V.; Harky, A. COVID-19 and Multiorgan Response. Curr. Probl. Cardiol. 2020, 45, 100618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Subbarao, K.; Mahanty, S. Respiratory Virus Infections: Understanding COVID-19. Immunity 2020, 52, 905–909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, J. Pathogenicity and Transmissibility of 2019-NCoV-A Quick Overview and Comparison with Other Emerging Viruses. Microbes Infect. 2020, 22, 69–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kampf, G.; Todt, D.; Pfaender, S.; Steinmann, E. Persistence of Coronaviruses on Inanimate Surfaces and Their Inactivation with Biocidal Agents. J. Hosp. Infect. 2020, 104, 246–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Harrel, S.K.; Molinari, J. Aerosols and Splatter in Dentistry: A Brief Review of the Literature and Infection Control Implications. J. Am. Dent. Assoc. 2004, 135, 429–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chia, P.Y.; Coleman, K.K.; Tan, Y.K.; Ong, S.W.X.; Gum, M.; Lau, S.K.; Lim, X.F.; Lim, A.S.; Sutjipto, S.; Lee, P.H.; et al. Detection of Air and Surface Contamination by SARS-CoV-2 in Hospital Rooms of Infected Patients. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 2800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wrapp, D.; Wang, N.; Corbett, K.S.; Goldsmith, J.A.; Hsieh, C.-L.; Abiona, O.; Graham, B.S.; McLellan, J.S. Cryo-EM Structure of the 2019-NCoV Spike in the Prefusion Conformation. Science 2020, 367, 1260–1263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hamming, I.; Timens, W.; Bulthuis, M.L.C.; Lely, A.T.; Navis, G.J.; van Goor, H. Tissue Distribution of ACE2 Protein, the Functional Receptor for SARS Coronavirus. A First Step in Understanding SARS Pathogenesis. J. Pathol. 2004, 203, 631–637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, H.; Zhong, L.; Deng, J.; Peng, J.; Dan, H.; Zeng, X.; Li, T.; Chen, Q. High Expression of ACE2 Receptor of 2019-NCoV on the Epithelial Cells of Oral Mucosa. Int. J. Oral Sci. 2020, 12, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabino-Silva, R.; Jardim, A.C.G.; Siqueira, W.L. Coronavirus COVID-19 Impacts to Dentistry and Potential Salivary Diagnosis. Clin. Oral Investig. 2020, 24, 1619–1621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Banakar, M.; Bagheri Lankarani, K.; Jafarpour, D.; Moayedi, S.; Banakar, M.H.; MohammadSadeghi, A. COVID-19 Transmission Risk and Protective Protocols in Dentistry: A Systematic Review. BMC Oral Health 2020, 20, 275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hindson, J. COVID-19: Faecal-Oral Transmission? Nat. Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2020, 17, 259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Graaf, M.; Beck, R.; Caccio, S.M.; Duim, B.; Fraaij, P.L.; Le Guyader, F.S.; Lecuit, M.; Le Pendu, J.; de Wit, E.; Schultsz, C. Sustained Fecal-Oral Human-to-Human Transmission Following a Zoonotic Event. Curr. Opin. Virol. 2017, 22, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peng, X.; Xu, X.; Li, Y.; Cheng, L.; Zhou, X.; Ren, B. Transmission Routes of 2019-NCoV and Controls in Dental Practice. Int. J. Oral Sci. 2020, 12, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Estrich, C.G.; Mikkelsen, M.; Morrissey, R.; Geisinger, M.L.; Ioannidou, E.; Vujicic, M.; Araujo, M.W.B. Estimating COVID-19 Prevalence and Infection Control Practices among US Dentists. J. Am. Dent. Assoc. 2020, 151, 815–824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- American Dental Association. ADA Interim Guidance for Minimizing Risk of COVID-19 Transmission Risk when Treating Dental Emergencies. Available online: https://www.ada.org/publications/ada-news/2020/april/ada-releases-interim-guidance-on-minimizing-covid-19-transmission-risk-when-treating-emergencies (accessed on 1 April 2020).

- Centers for Disease and Prevention. Guidance for Dental Settings: Interim Infection Prevention and Control Guidance for Dental Settings during the Coronavirus Disease (COVID-19) Pandemic. Available online: Https://Www.Cdc.Gov/Coronavirus/2019-Ncov/Hcp/Dental-Settings.Html (accessed on 29 June 2020).

- World Health Organization. Clinical Management of Severe Acute Respiratory Infection When Novel Coronavirus (2019-NCoV) Infection Is Suspected: Interim Guidance. 2020. Available online: https://Www.Who.Int/Publications-Detail/Clinical-Management-of-Severe-Acute-Respiratory-InfecTion-When-Novel-Coronavirus-(Ncov)-Infection-Is-Suspected (accessed on 17 February 2020).

- Dzien, C.; Halder, W.; Winner, H.; Lechleitner, M. Covid-19 Screening: Are Forehead Temperature Measurements during Cold Outdoor Temperatures Really Helpful? Wien. Klin. Wochenschr. 2021, 133, 331–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hsiao, S.-H.; Chen, T.-C.; Chien, H.-C.; Yang, C.-J.; Chen, Y.-H. Measurement of Body Temperature to Prevent Pandemic COVID-19 in Hospitals in Taiwan: Repeated Measurement Is Necessary. J. Hosp. Infect. 2020, 105, 360–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bescos, R.; Casas-Agustench, P.; Belfield, L.; Brookes, Z.; Gabaldón, T. Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19): Emerging and Future Challenges for Dental and Oral Medicine. J. Dent. Res. 2020, 99, 1113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samaranayake, L.P.; Peiris, M. Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome and Dentistry: A Retrospective View. J. Am. Dent. Assoc. 2004, 135, 1292–1302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Hu, T.; Li, G.; Zuo, Y.; Zhou, X. Risk of Hepatitis B Virus Transmission via Dental Handpieces and Evaluation of an Anti-Suction Device for Prevention of Transmission. Infect. Control. Hosp. Epidemiol. 2007, 28, 80–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fehr, A.R.; Perlman, S. Coronaviruses: An Overview of Their Replication and Pathogenesis. Methods Mol. Biol. 2015, 1282, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Yoon, J.G.; Yoon, J.; Song, J.Y.; Yoon, S.-Y.; Lim, C.S.; Seong, H.; Noh, J.Y.; Cheong, H.J.; Kim, W.J. Clinical Significance of a High SARS-CoV-2 Viral Load in the Saliva. J. Korean Med. Sci. 2020, 35, e195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kelly, N.; Nic Íomhair, A.; McKenna, G. Can Oral Rinses Play a Role in Preventing Transmission of Covid 19 Infection? Evid. Based Dent. 2020, 21, 42–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bidra, A.S.; Pelletier, J.S.; Westover, J.B.; Frank, S.; Brown, S.M.; Tessema, B. Rapid In-Vitro Inactivation of Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) Using Povidone-Iodine Oral Antiseptic Rinse. J. Prosthodont. 2020, 29, 529–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bidra, A.S.; Pelletier, J.S.; Westover, J.B.; Frank, S.; Brown, S.M.; Tessema, B. Comparison of In Vitro Inactivation of SARS CoV-2 with Hydrogen Peroxide and Povidone-Iodine Oral Antiseptic Rinses. J Prosthodont 2020, 29, 599–603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gottsauner, M.J.; Michaelides, I.; Schmidt, B.; Scholz, K.J.; Buchalla, W.; Widbiller, M.; Hitzenbichler, F.; Ettl, T.; Reichert, T.E.; Bohr, C.; et al. A Prospective Clinical Pilot Study on the Effects of a Hydrogen Peroxide Mouthrinse on the Intraoral Viral Load of SARS-CoV-2. Clin. Oral Investig. 2020, 24, 3707–3713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melo, M.a.S.; Rolim, J.P.M.L.; Passos, V.F.; Lima, R.A.; Zanin, I.C.J.; Codes, B.M.; Rocha, S.S.; Rodrigues, L.K.A. Photodynamic Antimicrobial Chemotherapy and Ultraconservative Caries Removal Linked for Management of Deep Caries Lesions. Photodiagn. Photodyn. Ther. 2015, 12, 581–586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Melo, M.A.S. Photodynamic Antimicrobial Chemotherapy as a Strategy for Dental Caries: Building a More Conservative Therapy in Restorative Dentistry. Photomed. Laser Surg. 2014, 32, 589–591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balhaddad, A.A.; Garcia, I.M.; Ibrahim, M.S.; Rolim, J.P.M.L.; Gomes, E.A.B.; Martinho, F.C.; Collares, F.M.; Xu, H.; Melo, M.A.S. Prospects on Nano-Based Platforms for Antimicrobial Photodynamic Therapy Against Oral Biofilms. Photobiomodul. Photomed. Laser Surg. 2020, 38, 481–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rolim, J.P.M.L.; de-Melo, M.A.S.; Guedes, S.F.; Albuquerque-Filho, F.B.; de Souza, J.R.; Nogueira, N.A.P.; Zanin, I.C.J.; Rodrigues, L.K.A. The Antimicrobial Activity of Photodynamic Therapy against Streptococcus Mutans Using Different Photosensitizers. J. Photochem. Photobiol. B 2012, 106, 40–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balhaddad, A.A.; AlQranei, M.S.; Ibrahim, M.S.; Weir, M.D.; Martinho, F.C.; Xu, H.H.K.; Melo, M.A.S. Light Energy Dose and Photosensitizer Concentration Are Determinants of Effective Photo-Killing against Caries-Related Biofilms. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 7612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alfirdous, R.A.; Garcia, I.M.; Balhaddad, A.A.; Collares, F.M.; Martinho, F.C.; Melo, M.A.S. Advancing Photodynamic Therapy for Endodontic Disinfection with Nanoparticles: Present Evidence and Upcoming Approaches. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 4759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balhaddad, A.A.; Xia, Y.; Lan, Y.; Mokeem, L.; Ibrahim, M.S.; Weir, M.D.; Xu, H.H.K.; Melo, M.A.S. Magnetic-Responsive Photosensitizer Nanoplatform for Optimized Inactivation of Dental Caries-Related Biofilms: Technology Development and Proof of Principle. ACS Nano 2021, 15, 19888–19904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Teófilo, M.Í.S.; de Carvalho Russi, T.M.A.Z.; de Barros Silva, P.G.; Balhaddad, A.A.; Melo, M.A.S.; Rolim, J.P.M.L. The Impact of Photosensitizers Selection on Bactericidal Efficacy of PDT against Cariogenic Biofilms: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Photodiagn. Photodyn. Ther. 2020, 33, 102046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leite, D.P.V.; Paolillo, F.R.; Parmesano, T.N.; Fontana, C.R.; Bagnato, V.S. Effects of Photodynamic Therapy with Blue Light and Curcumin as Mouth Rinse for Oral Disinfection: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Photomed. Laser Surg. 2014, 32, 627–632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Araújo, N.C.; Fontana, C.R.; Gerbi, M.E.M.; Bagnato, V.S. Overall-Mouth Disinfection by Photodynamic Therapy Using Curcumin. Photomed. Laser Surg. 2012, 30, 96–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panhóca, V.H.; Esteban Florez, F.L.; Corrêa, T.Q.; Paolillo, F.R.; de Souza, C.W.O.; Bagnato, V.S. Oral Decontamination of Orthodontic Patients Using Photodynamic Therapy Mediated by Blue-Light Irradiation and Curcumin Associated with Sodium Dodecyl Sulfate. Photomed. Laser Surg. 2016, 34, 411–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ricci Donato, H.A.; Pratavieira, S.; Grecco, C.; Brugnera-Júnior, A.; Bagnato, V.S.; Kurachi, C. Clinical Comparison of Two Photosensitizers for Oral Cavity Decontamination. Photomed. Laser Surg. 2017, 35, 105–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Kellesarian, S.V.; Qayyum, F.; de Freitas, P.C.; Akram, Z.; Javed, F. Is Antimicrobial Photodynamic Therapy a Useful Therapeutic Protocol for Oral Decontamination? A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Photodiagn. Photodyn. Ther. 2017, 20, 55–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Namvar, M.A.; Vahedi, M.; Abdolsamadi, H.-R.; Mirzaei, A.; Mohammadi, Y.; Azizi Jalilian, F. Effect of Photodynamic Therapy by 810 and 940 Nm Diode Laser on Herpes Simplex Virus 1: An in Vitro Study. Photodiagn. Photodyn. Ther. 2019, 25, 87–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, J.; Zhang, Y.; Zhiyue, L. Successful Treatment of Oral Human Papilloma by Local Injection 5-Aminolevulinic Acid-Mediated Photodynamic Therapy: A Case Report. Photodiagn. Photodyn. Ther. 2019, 26, 134–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heßling, M.; Hönes, K.; Vatter, P.; Lingenfelder, C. Ultraviolet Irradiation Doses for Coronavirus Inactivation—Review and Analysis of Coronavirus Photoinactivation Studies. GMS Hyg. Infect. Control. 2020, 15, Doc08. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Balhaddad, A.A.; Mokeem, L.; Khajotia, S.S.; Florez, F.L.E.; Melo, M.A.S. Perspectives on Light-Based Disinfection to Reduce the Risk of COVID-19 Transmission during Dental Care. BioMed 2022, 2, 27-36. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomed2010003

Balhaddad AA, Mokeem L, Khajotia SS, Florez FLE, Melo MAS. Perspectives on Light-Based Disinfection to Reduce the Risk of COVID-19 Transmission during Dental Care. BioMed. 2022; 2(1):27-36. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomed2010003

Chicago/Turabian StyleBalhaddad, Abdulrahman A., Lamia Mokeem, Sharukh S. Khajotia, Fernando L. Esteban Florez, and Mary A. S. Melo. 2022. "Perspectives on Light-Based Disinfection to Reduce the Risk of COVID-19 Transmission during Dental Care" BioMed 2, no. 1: 27-36. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomed2010003

APA StyleBalhaddad, A. A., Mokeem, L., Khajotia, S. S., Florez, F. L. E., & Melo, M. A. S. (2022). Perspectives on Light-Based Disinfection to Reduce the Risk of COVID-19 Transmission during Dental Care. BioMed, 2(1), 27-36. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomed2010003