1. Introduction

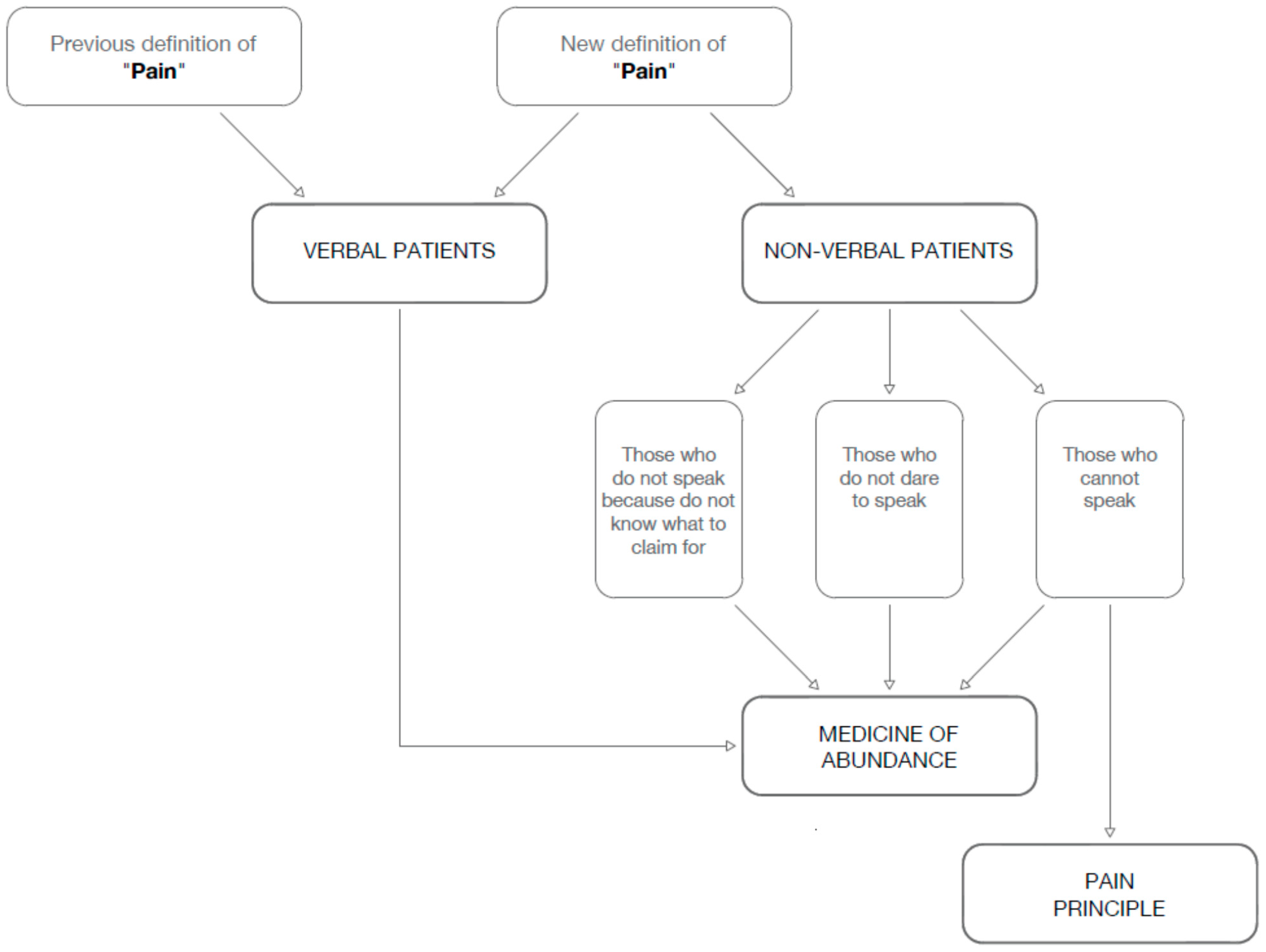

The international definition of the word pain has recently been changed. Until recently, this definition did not include people who cannot express themselves to describe and claim treatment for their pain. Now, the IASP has finally decided to broaden the definition of “pain”, to include children and the mentally disabled and people in a coma [

1]. The current definition is: “An unpleasant sensory and emotional experience associated with, or resembling that associated with actual or potential tissue damage” [

2]. The previous definition required that pain be “described” by the patient; this served to give weight to the words and will of those who suffered, to emphasize that doctors and nurses cannot close their eyes in front of a complaint of pain, even though they might suppose that it is fantasy or simulation. Nowadays, this concern remains valid, but the current definition includes every living being, even those who cannot communicate through words.

The community’s attention must be focused on pain, especially on the pain of those who have no voice. Some have no voice because of an illness or because of their age; but there are three more types of patients who cannot claim for their needs. The first group is made up of those who do not speak because of subjection towards doctors: they are so concerned by a paternalistic approach that they delegate every decision to their caregiver [

3]. The second group is made up of patients who do not speak because they do not know what they can ask: they do not know the possibilities and the offers of modern science [

4]. A third group is made up of those who may be resigned in front of a chronic pain or because of a severe depression [

5].

A fourth group has appeared during the COVID-19 pandemic: it is a new entry in this scenario. This group of people does not express its wishes as a mixture of the previous groups. Many people in the COVID-19 era are so scared and overwhelmed by the pandemia, isolated and remained without several healthcare services, that they do not dare to speak, do not know what to ask, and feel severe anxiety and sadness [

6,

7].

COVID-19 has brought a new phenomenon into our lives: a further monadization of human beings who already in many parts of the world were painfully experiencing the phenomenon of social isolation. The further distancing and separation of people has led to an aggravation of the inability and impossibility of expressing oneself, of reclaiming one’s right to health and pain relief, provoking a decrease of access to analgesic therapies [

8,

9]. Many reports show how the level of suffering and social fear has drastically increased, also because the isolation of people was the only criterion adopted for the first months to prevent the pandemic, while waiting for the vaccine or suitable antiviral drugs [

10]. However, even when these pharmacological aids arrived, the social isolation continued, as did the decrease in medical visits and hospitalizations for many pathological phenomena, given that a large part of medical and hospital resources were dedicated to the pandemic and that doctors maintain a high level of contagion prevention by decreasing the opportunities to visit potentially Coronavirus-infected patients at home [

11,

12].

This opens up our responsibility to two key points for the approach to pain of those who cannot express themselves in words (

Figure 1).

2. The Medicine of Abundance

In this pandemic, it is urgent give voice to all voiceless people, with particular regard to their physical or psychological pain. The whole healthcare system should become comfortable and friendly as it has never been. Unfortunately, it seems that the COVID-19 pandemic has made it less welcoming for all. In this pandemic period, we have seen the damage created when the health system has lost references, in particular in one of its columns, family medicine: “(…) confinement drives risk for unhealthy diets, decreased physical activity, mental health related concerns, in parallel to delayed care-seeking due to fear of contracting COVID-19. Another weakness in the current COVID-19 response is the focus on hospital care which overlooks the importance of Primary Care in guaranteeing continuity of care” [

13]. This has led people to feel alone, to bureaucratizing illness, quarantine, and personal suffering, increasing anxiety and suffering and leading to the clogging of emergency rooms and hospital care departments; at the same time, it has accentuated the personal suffering of all the sick who saw their needs rejected because many departments had to stop their activities to prevent COVID infections; because of COVID, a lot of medical staff were diverted to the infectious wards. The increase in waiting times in the emergency room has led to suffering, as well as the decrease in surgical interventions, specialist visits, reduced hospitalizations for psychiatric patients, psychological consultations. Having focused all the attention on the COVID phenomenon has saved many lives, but has neglected countless ones, who have been left alone [

14]. The loneliness of patients is a very old problem, which now has been unveiled and should be faced.

To welcome and overcome the pain of everyone, even those who cannot express themselves in words, the hospital must transform itself from a “container of analgesic tools” into a real “analgesic tool” [

15]. So far, we have had a conception of public health and hospitals as a service aimed at directing the sick citizen to the health professional or to the medical department best suited to their needs. The doctor or the ward would then take care of them according to the address assigned at the entrance. This model has two flaws. The first is that the hospital remains neutral with respect to the citizen’s need for health, and acts as a screening service, directing them to the most appropriate service. The hospital and the health system therefore behave as providers of services, from which they remain extraneous and of which they act as organizers. The second flaw is that in this way, doctors begin their relationship with the patient who arrives from the hospital-screener with a sort of “prejudice”, that is, an preemptive judgment: they are asked to offer a service limited to the label that has been affixed to the patient, and will see the patient only in the circumscribed light of that label. These two paths are fallacious because they skip the main point required by modern medicine, namely, the integral health approach. An integral health approach, is when the patient is not seen as a client, and the doctor is not seen as a manager or a service provider: it is, first of all, hospitality. For this reason, the hospital must be prosthetic, it should a prolongment of the patient’s abilities, in particular when he/she is disabled; it should become a place of wellbeing; the entrance into the hospital must already be a first relief. At the moment of this entrance, the patient must find a welcoming, serene environment, clear in explanations, even when they cannot or do not dare to speak.

When the patients are referred to a ward or a doctor by a bureaucratic system made up of people who do not know them, the second flaw occurs: the doctors see the patient only through the lens of their specialty or subspecialty, in a health system of hyperspecialization, which leads to subsequent and further consultations, making the patient pass from one doctor to another.

The lack of a medicine where doctors are not only service-providers, but are truly trusted, leads to disorientation and anxiety, and to an increase in physical pain. In many countries, the network of family medicine is insufficient and even with the ever more frequent cuts to healthcare, the situation is getting worse. It would indeed be necessary for doctors to become protagonists of the patient’s health instead of sending them back to consultants unknown to the patient, certainly necessary in many cases, but with whom the trusted doctor should interface and talk.

This requires what I have defined a “medicine of abundance” (MoA). MoA [

16] means taking charge of the whole patient, not just of their signs and symptoms: it is accompanying them into a warm and comfortable path. The MoA consists of two steps: to cut unnecessary expenses and waste in healthcare, and to invest in two key sectors, namely, the motivation of staff and the requalification of hospitalization environments. Staff motivation is often threatened by exhausting workloads and cuts to personnel, and this can lead to loss of enthusiasm and even suffering, which can become contagious for the patients. Hospital environments are too often cold, crowded, noisy, with unstable hours adapted to the patient, with excessive impediments to visits from relatives. The MoA should turn the hospital into an analgesic tool: entering a hospital should be releasing and relieving to the patient: a motivated staff and a relieving environment are the first analgesic tools.

MoA is a holistic view of the patient; it is opposed to the “medicine of protocols” that considers the patient as a combination of organs and diseases. Protocols are often useful allies of patients and health providers; but the protocols are made for the “standard patient”; for those who cannot or do not know how to express, it is necessary to adapt and modulate our interpretative skills and observation. The doctors’ frontier consists precisely in expanding their observation: so far, we have looked at the patient vertically, observing their “before” (anamnesis) and their “after” (prognosis). Now, it is necessary to add to this a horizontal vision taking charge of patients’ external environment (family, job, economic difficulties) and of their internal one (relational problems, aspirations, compliance). It is precisely in this second dimension that we need to work to attain a MoA, where doctors are not just employees but master and get satisfaction from their work. It is necessary to avoid the “SUV effect” [

16], the fake sense of safety doctors feel for the many tests available (as several drivers of very powerful cars do behind the many potentialities of their cars), while decreasing their level of attention.

MoA (the preferential choice for caring for people at home, when possible, the mother in the ward with the child, the respect for the rhythms and needs of the patient) has a strong complimentary importance for health and for the struggle against pain [

17,

18]. It is a Copernican revolution: from the hospital considered as an impersonal hub, to the hospital itself seen as a health treatment. Analgesia must not only take place “on request” or under the doctor’s instructions, but must be innate in the place of care. The absence of this wide vision—particularly important for the patients who cannot express themselves in words—makes the hospital just an architectural work.

3. The Pain Principle

A recent study of COVID-19 pediatric patients performed by pediatric bioethicists stated: “We must ensure that no subgroup is overlooked or left out”. Because some patients suffer unjustly owing to situational vulnerabilities, fairness may require that we focus more efforts toward those children at risk of the greatest harms. Transparency will mean making clear that, despite uncertainty, our decisions and choices are reasoned, evidence based, and strive for equity [

19]. Patients who cannot express themselves with words, or because the pandemic has overshadowed their voice, should be carefully addressed.

This highlights the importance of assessing and detecting pain in those who cannot speak. This is an ancient problem that recent advances in pain assessment can help overcome. A protocol called the “pain principle” has been proposed which helps doctors and parents to understand when the child and the non-verbal patient actually need painkilling treatment, and in particular, when it is necessary to suspend therapies due to their excessive intolerability from the point of view of the pain they cause or fail to prevent. It is important to understand that the so-called therapeutic obstinacy is not the use of ineffective drugs or treatments, because this falls under the name of futility. Therapeutic obstinacy is the use of drugs or treatments that cause discomfort, pain, or anxiety without benefiting. This is why the “pain principle” program is particularly useful [

20,

21].

The fight against pain also requires that decisions about the end-of-life of those who cannot speak are made in accordance with the objective measurement of the patient’s pain. I proposed the “pain principle” to realistically evaluate those who, although unable to express themselves in words (children, mentally impaired patients, people in coma), express their level of pain in hidden but valid signs, as if they were saying if they can or cannot stand the treatment. These signs are the various scales of suffering of the patient in a coma, the evaluation of the stress hormones in saliva, the measurement of the activation of the sympathetic system, a sign of stress, by measuring the variability of heart rate or palmar or plantar skin conductivity.

The measurement of pain helps to skip two basic errors: a too rapid recourse to the suspension of treatment, and the prejudice against opioids. It is as if we let the non-verbal patient speak, interpreting their signals through validated tools, and are suspending or reducing the treatments according to their real state of suffering.

In this regard, much can be done to help the patient who suffers. On one side, there is physical pain, which fortunately today the law requires not only to treat but also to measure in the hospitals. We have excellent drugs for the treatment of pain: from paracetamol to the strongest opioids, with all the strategies of combination between them, of opioid rotation, of the use of adjuvant drugs, and at the right moment, of sedatives that have the function of reversibly decreasing consciousness in the most serious moments. On the other side, there is a more intimate pain, the psychological one: it is the existential suffering which is very widespread, and certainly weighs on those who have severe physical deficits or are struggling with a terminal illness. We cannot shy away from the available therapies, both pharmacological and cognitive-behavioral, which have a high success rate. We must make these possibilities known, offer them to the sick, and not choose shortcuts on their behalf; as Maria Nabal [

22], the editor of the Spanish magazine

Medicina Paliativa, wrote: “If professionals and family members project their suffering onto the patient, they can be tempted to sedate indiscriminately. In an attempt to safeguard what we mistakenly understand as palliation, we take away the autonomy of the patient.” Alongside this, the International Association for Palliative Care states that “In countries and states where euthanasia is/or assisted suicide are legal, palliative care units should not be responsible for supervising or administering these practices” [

23]. Here comes the problem of the patient who “cannot speak”. Some patients cannot speak from a pathology or from their age and for them, the “pain principle” has been developed.