Abstract

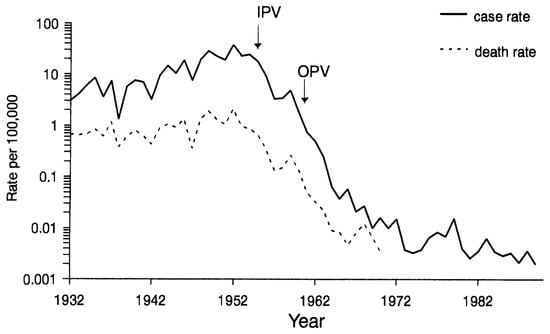

This study reviews the role of epidemiology in the United States in the late 19th and early 20th century, which led to recognition that poliomyelitis is an infectious disease and set the stage for subsequent developments in virology and immunology, the development of inactivated and live attenuated polio vaccines, and a dramatic worldwide decrease in poliomyelitis mortality and morbidity. Epidemiological studies in the United States were systematically reviewed from the mid-19th to early 20th centuries. Isolated cases and scattered small outbreaks of poliomyelitis in the mid-19th century led to epidemics of increasing size by the end of the century, causing public consternation, especially as the disease was considered “new” and had a predilection for young children. By the 1890s, the seasonal pattern of epidemics suggested that poliomyelitis might have an infectious etiology, but direct evidence of communicability or contagiousness was lacking, so an infectious etiology was not widely suspected until the early 20th century. Reports of bacterial isolations from spinal fluid and postmortem tissues suggested that poliomyelitis might be a bacterial disease, and simultaneous outbreaks of paralytic disease in humans and animals suggested a possible zoonotic basis. Although experimental studies showed that it was theoretically possible for flies to serve as vectors of poliovirus, and occasional cases of polio were likely caused by fly-borne transfer of poliovirus from human feces to human food, a fly abatement field trial showed convincingly that flies, whether biting or non-biting, could not explain the bulk of cases during polio epidemics. In conclusion, the early application of epidemiological evidence beginning in the late 19th century strongly suggested the infectious nature of the disease, distinct from previously identified conditions. Subsequent advances in virology and immunology from 1909 to 1954 proved that poliomyelitis was a viral disease with no natural animal host and made feasible the development of an inactivated trivalent poliovirus vaccine by Salk, and, subsequently, a live-attenuated trivalent poliovirus vaccine by Sabin.

Keywords:

poliomyelitis; epidemiology; history of medicine; bacteriology; virology; immunology; zoonosis; vector; poliovirus 1. Introduction

This review considers the emerging epidemiologic evidence from the mid-19th century to the beginning of the 20th century, which led to recognition in the United States that poliomyelitis is an infectious disease.

Isolated cases and small, geographically isolated outbreaks of probable poliomyelitis (“infantile paralysis”) were reported during the 18th and early 19th centuries [1]. These early cases were sufficiently characteristic to enable recognition of the disorder and to allow descriptions of typical clinical features but left those studying it puzzled concerning its etiology. Because poliomyelitis did not show a clear pattern of communicability, an infectious etiology was not suspected.

By the end of the 19th century, epidemics of increasing size caused increasing public consternation, especially as the disease was considered “new” and had a predilection for young children. By the 1890s, the seasonal pattern of the epidemics suggested to multiple investigators that poliomyelitis might be infectious, but several factors confounded this growing consensus, and at the time there was certainly no proof of this idea. The late 19th-century outbreaks and epidemics of poliomyelitis provided a much clearer understanding of the clinical phenomenology of poliomyelitis, provided the beginnings of clinical–pathological correlation, allowed for the separation of poliomyelitis from other myelopathies and other disorders causing acute or subacute weakness, and produced a rapid expansion in orthotic technologies and orthopedic surgeries to alleviate the resulting disabilities and deformities [2,3,4]. However, the contagiousness of poliomyelitis had long remained an open and contentious question, with inconclusive evidence of communicability even among those residing in close proximity (e.g., within families). In trying to elaborate an infectious theory of poliomyelitis, several misleading reports in the last decade of the 19th century led to consideration of whether poliomyelitis is a bacterial disease and whether it might be transmitted from animals to man—a zoonosis.

By the second decade of the 20th century, poliomyelitis was shown to be a viral disease [5,6], and the various putative bacterial causes were recognized to be merely contaminants. The early 20th century also saw the advent of the vector theory of poliomyelitis transmission, with increasing awareness that the poliovirus is excreted in feces, that poliovirus can be detected in sewage and in flies, and that flies can transmit poliomyelitis under experimental conditions. The vector-borne theory of poliomyelitis was abandoned by the mid-20th century after fly abatement field trials proved ineffective in modifying the course of poliomyelitis epidemics, but the zoonotic theory was not fully disproved until the latter half of the 20th century.

2. Early Sporadic Cases and Outbreaks

Beginning in the mid-1830s and 1840s, small outbreaks of childhood paralysis began to be reported, first by John Badham who described a cluster of four cases in young children in the midland town of Worksop, England, in 1835 [7], and then in the United States by George Colmer (1807–1878) (Figure 1). Colmer was born in London, received his MD degree from the Medical College of Louisiana in 1838, and then practiced in Springfield, Louisiana, until his death. His cursory notice of an outbreak of childhood paralysis among infants and toddlers in West Feliciana, Louisiana, during the summer and fall of 1841, was entitled “Paralysis in teething children.” Colmer’s report amounted to only a paragraph in which he described a paralytic outbreak in children that is recognizable in retrospect as poliomyelitis [8,9]:

Figure 1.

Louisiana physician George Colmer (1807–1878). Colmer briefly described an outbreak of poliomyelitis, which occurred in 1841 in West Feliciana, Louisiana, the first such outbreak in the world. Reprinted from [9] with permission of Wolters Kluwer Health, Inc. License number 6074351241461. The image has been cropped from the original.

While on a visit… my attention was called to a child about a year old, then slowly recovering from an attack of hemiplegia. The parents, (who were people of intelligence and unquestionable veracity,) told me that eight or ten other cases of either hemiplegia or paraplegia, had occurred during the preceding three or four months within a few miles of their residence, all of which had either completely recovered, or were decidedly improving. The little sufferers were invariably under two years of age, and the cause seemed to be the same in all—namely, teething.[8] (p. 248)

Colmer’s report was not recognized until much later, but then it was repeatedly cited, especially in the early years of the 20th century [10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18]. Colmer did recognize poliomyelitis as a distinct entity, affecting teething children (ages 1–2), causing paralysis (with subsequent improvement or recovery in most), and occurring during the late summer and early fall in a small rural area.

German orthopedist Jakob Heine (1800–1879) had recognized poliomyelitis (infantile paralysis) as a sporadic clinical entity in 1840 [19], three years before Colmer’s report, though Colmer was apparently unaware of this [8]. From the time of Colmer’s report of though the 1860s, poliomyelitis (or infantile paralysis, as it was generally referred to in the United States at the time) was apparently mostly a sporadic condition that was seldom discussed in the American medical literature. Poliomyelitis has such a characteristic presentation that even modest outbreaks would not likely be overlooked (even if labeled as something else). Instead, it is now clear that poliomyelitis emerged as a significant epidemic disease during the late 19th and early 20th centuries, but a full appreciation and explanation for this was long delayed [20,21].

Beginning in the late 1860s, one of the first to investigate infantile paralysis in the United States was William Alexander Hammond (1828–1900) (Figure 2) of the College of Physicians and Surgeons in New York, who was then establishing himself as a neurologist after his humiliating though largely unjustified court-martial as Surgeon General of the Union Army during the U.S. Civil War [22,23,24,25,26,27,28]. From December 1865 to December 1870, Hammond treated 98 cases of “organic infantile paralysis” that were mostly consistent with poliomyelitis [26]. Using a Duchenne trocar, he obtained muscle biopsies and described the progressive secondary degenerative changes in the muscles of affected patients [24,26]. Despite Hammond’s relative wealth of clinical experience with this disorder for the time, he acknowledged his ignorance concerning its etiology in his textbook, A Treatise on Diseases of the Nervous System (1871)—the first textbook of neurology in the United States [28,29,30]:

Figure 2.

New York neurologist and former U.S. Surgeon General William Alexander Hammond (1828–1900), c1877. In the late 1860s, Hammond was one of the first physicians in the United States to investigate infantile paralysis (poliomyelitis), and he identified progressive secondary degenerative changes in muscle biopsies after onset of the disease. Hammond acknowledged his ignorance of the cause of the disorder. Etching by E.B. Hall. Courtesy of the US National Library of Medicine [31] (public domain).

Little is known of the etiology of organic infantile paralysis. … In the great majority of the cases that have come under my observation, no cause could be reasonably assigned.[26] (p. 691)

On 8 November 1873, in a lecture at the College of Physicians and Surgeons in New York City, New York neurologist Edward Constant Séguin (1843–1896) (Figure 3) gave a clear and concise clinical-pathological description of the disease, based on anecdotal case reports and small case series from the limited number of prior outbreaks [32,33,34]. He also indicated (by the inserted question marks) aspects of the pathogenesis, which he suspected were true, but which had not been proven.

Figure 3.

Edward Constant Seguin (1843–1896). Reprinted from Ref. [33] (public domain).

In brief, infantile spinal paralysis may be defined as an acute febrile affection, resulting in generalized paralysis, which shortly disappears from all but a limited part of the body, where akinesis [i.e., lack of movement due to weakness] persists indefinitely without impairment of sensibility, is accompanied within a few weeks by atrophy of the palsied muscles, and is followed later by various deformities,—the result of altered balance of power at certain joints. The anatomical lesion of the disease consists in primary (?) atrophy of the nerve-cells of the anterior horns of the spinal cord (motor tract), and in secondary (?), complicating (?) myelitis.[32] (p. 25)

3. Recognizing the Seasonality of Poliomyelitis

In 1875, in an article on “The palsies of children,” Philadelphia neurologist Wharton Sinkler (1845–1910) (Figure 4)—a protégé of pioneering Philadelphia neurologist S. Weir Mitchell (1829–1914) and a future President of the American Neurological Association (in 1891) [35]—was the first to recognize the seasonal pattern of poliomyelitis incidence: because only the season of onset for 13 of his 57 cases (23%) was known, these data are aggregated and presented by season [36] (Figure 5).

Figure 4.

Philadelphia neurologist Wharton Sinkler (1845–1910). In 1875, Sinkler was the first to recognize the seasonal pattern of poliomyelitis. Reprinted from Ref. [35] (public domain).

Figure 5.

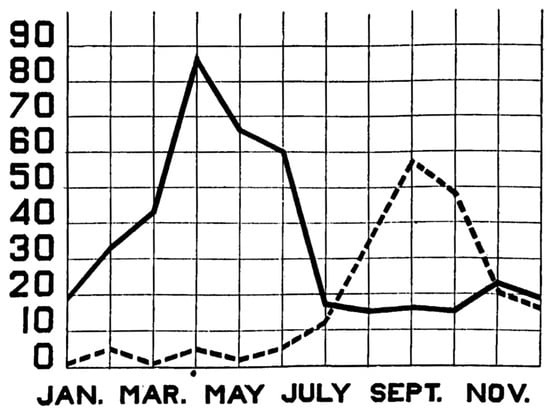

The seasonal pattern of incident cases of poliomyelitis as described by Wharton Sinkler (1875) and James Jackson Putnam (1893). Data from Refs. [36,37].

I observed, two or three years ago, that many of our cases of infantile palsy were said to have been attacked in the summer months, and since then I have carefully noted the time of year when the paralysis came on in each patient. … [Forty] of the fifty-seven cases were affected in the summer months; and if we add the seven which took place in May and September, which are generally hot months in this city, we find that all but ten of the fifty-seven cases occurred in hot weather. This fact has not, to my knowledge, been remarked before, and seems to me to have much bearing upon the causation of the disease. At any rate, it is evident that hot weather must have a marked influence in predisposing to the affection.[36] (p. 353)

Sinkler noted an earlier report that suggested Sydenham’s chorea was seasonal, but he did not speculate on the pathophysiologic basis of either disorder or the reasons for the seasonality of disease incidence. Instead, he concluded regarding seasonal childhood paralysis that “Nothing is known of the exciting cause” [36] (p. 353).

Sinkler’s report was highly cited into at least the 1890s and influenced the thinking of later neurologists and epidemiologists who considered the etiology of poliomyelitis [37,38]. He revisited the seasonality of poliomyelitis in several later papers, analyzing cases at the Philadelphia Orthopedic Hospital and Infirmary for Nervous Diseases in 1890 (270 cases for which the month of onset was recorded, from a total of 350 cases; time period not provided), and again in 1908 (507 cases for which the month of onset was provided; total cases observed and exact time period covered were again not provided) [39,40,41].

In 1893, Boston neurologists James Jackson Putnam (1846–1918) (Figure 6), a founding member of the American Neurological Association, and Edward Wyllys Taylor (1836–1932) (Figure 7) acknowledged Sinkler’s earlier recognition that poliomyelitis is “pre-eminently a disease of the summer months of the year” [38,42,43,44,45,46]. Putnam and Taylor analyzed cases from the Massachusetts General Hospital and noted “with the exception that, so far as the small aggregate of numbers prove[s] anything, they show that among us there is a greater prevalence of the dreaded affection in September than in August [38] (Figure 5). In the same report, Putnam and Taylor reported a concerning increase in the incidence of poliomyelitis from the prior year, a finding that was consistent with the experience at the Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston’s Children’s Hospital, the Boston Dispensary, and private consultation practices over that interval [38]. They noted an increase from 6 cases from August to November 1892 to 20 cases in the same interval the following year [38].

Figure 6.

Boston neurologist James Jackson Putnam (1846–1918), a founding member of the American Neurological Association. In 1893, with colleague Edward Wyllys Taylor, Putnam analyzed cases of poliomyelitis seen at the Massachusetts General Hospital, noting their seasonal pattern and a concerning significant increase from the prior year. Reprinted from [47] (public domain).

Figure 7.

Boston neurologist Edward Wyllys Taylor (1836–1932). Reprinted from Ref. [48] (public domain).

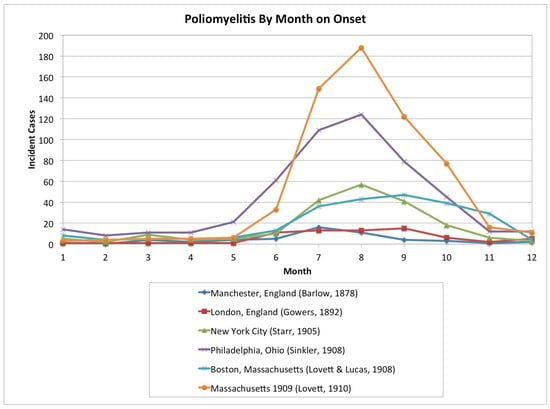

In addition to the reports by Sinkler [36,39,40,41], and the report by Putnam and Taylor [38], others in the United States and elsewhere collected case series that supported a seasonal pattern for poliomyelitis (Figure 8). Other fairly large case series that supported a seasonal pattern, which were not based on assessment of a single outbreak or epidemic, included confirmatory reports by the following individuals: (1) British physician William H. Barlow, Consulting Physician to the Dispensary, General Hospital, and Dispensary for Sick Children in Manchester, England, in 1878 (53 cases); (2) British neurologist William Richard Gowers (1845–1915) at the National Hospital for the Paralysed and Epileptic in London, England (70 cases); (3) New York neurologist Moses Allen Starr (1854–1932) from New York City (202 cases); and (4) Boston orthopedic surgeon Robert Williamson Lovett (1859–1924)—later famous as the physician who diagnosed Franklin Delano Roosevelt’s case of poliomyelitis in 1921 and for his work on the mechanics of the spine—with pediatrician William P. Lucas (1880–1961), at the Boston Children’s Hospital (239 cases) [49,50,51,52,53,54].

Figure 8.

Poliomyelitis cases by month of onset from several case series and from surveillance data for the state of Massachusetts for 1909. The various studies show a fairly consistent pattern of maximum poliomyelitis incidence in the late summer and early autumn. Graph by Douglas J. Lanska, MD, MS, MSPH. Data from Refs. [40,49,50,51,53,55].

4. The 1894 Vermont Polio Epidemic

The first significant epidemic of polio in the United States occurred in Vermont in 1894 and was reported in a series of publications by Charles Solomon Caverly (1856–1918) (Figure 9), President of the Vermont State Board of Health, and selected colleagues [56,57,58,59,60,61,62,63,64]. Initially, after soliciting input from physicians in the state, Caverly presented a preliminary report concerning 123 cases of “an acute nervous disease, which was almost invariably attended with some paralysis” [52] (p. 1). Cases began appearing in June in Rutland County, in a portion of the Otter Creek Valley. There was a “general feeling of uneasiness that was perceptible among the people in regard to the ‘new disease’ that was affecting the children” [56] (p. 1).

Figure 9.

Vermont public health physician Charles Solomon Caverly (1856–1918). In 1894, Caverly led the investigation and reporting of the then-largest epidemic of poliomyelitis in the world, affecting 132 people in Rutland County, Vermont. Reprinted from Ref. [61] (public domain).

In his initial preliminary report, Caverly raised two possible diagnostic possibilities: epidemic cerebro-spinal meningitis [now recognized as meningococcal meningitis] and acute poliomyelitis anterior [56].

The initial fever, followed in a few days by definite motor paralysis, of which a certain percentage recover in a few weeks, the rest suffering permanent impairment of some muscles, offers a fair picture of the average case of Poliomyelitis Anterior, while the high fever, muscular rigidity, and hyperaesthesia, are not characteristic of this disease. The season of the year, the absence of special sense symptoms, especially deafness, as a sequella in this epidemic, the low mortality, the absence of the very characteristic purpuric eruption, are strong arguments against the theory of Cerebro-Spinal Meningitis. It is now well established that the other disease, Poliomyelitis, is occasionally epidemic. Such epidemics have been noted in at least three instances in Europe, and one is reported by Putnam as occurring near Boston. The Stockholm epidemic [of 1887] reported by Medim [sic, Swedish pediatrician Karl Oscar Medin (1847–1927), who investigated an outbreak of 44 cases] is in many respects quire similar to the one which I have reported.[56] (p. 4)

In retrospect, on the strength of the evidence supplied by Caverly, the correct diagnosis was clearly poliomyelitis. However, as a public health physician, Caverly felt unsure of the diagnosis in these cases. He sought the advice of several clinical specialists, and perhaps predictably he received divergent opinions. New York pediatrician Abraham Jacobi (1830–1919) (Figure 10), a founder of pediatric medicine in the United States, opined without equivocation that it was epidemic cerebrospinal meningitis, while New York neurologists Moses Allen Starr (Figure 11) and Charles Loomis Dana (1852–1935) (Figure 12), both leading neurologists in the country at that time, correctly recognized this as poliomyelitis [65,66,67].

Figure 10.

New York pediatrician Abraham Jacobi (1830–1919). Jacobi was consulted concerning the 1894 epidemic of poliomyelitis in Rutland County, Vermont, but initially incorrectly diagnosed the causes as epidemic cerebro-spinal (meningococcal) meningitis. To his credit, he later corrected his diagnosis to poliomyelitis. Credit: George Grantham Bain Collection, Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division, Washington, D.C. [68] (public domain).

Figure 11.

New York neurologist Moses Allen Starr (1854–1932). Starr was consulted concerning the 1894 epidemic of poliomyelitis in Rutland County, Vermont, and correctly diagnosed the condition as poliomyelitis. Credit: Middlebury College Special Collections, Middlebury, Vermont [69].

Figure 12.

New York neurologist Charles Loomis Dana (1852–1935). In 1892, Dana was among the first in the United States to suggest an infectious etiology for poliomyelitis. Dana was consulted concerning the 1894 epidemic of poliomyelitis in Rutland County, Vermont, and correctly diagnosed the condition as poliomyelitis. Courtesy of the U.S. National Library of Medicine [70] (public domain). Edited by Douglas J. Lanska, MD, MS, MSPH.

Jacobi, basing his impressions on written case descriptions provided by Caverly, replied with a firm conviction that the cases were affected by meningitis, even though he noted the unusual paralytic presentation of the cases and the very low mortality (if this had been, in fact, meningitis):

All your cases belong to the same class, cerebro-spinal meningitis. They prove that nature does not walk in ruts as most of our text-books do, and that transitions and variations are common. … The frequency of paralysis in your cases is something very uncommon; so is your low mortality; both prove that your cases were more spinal than cerebral.[57] (p. 675)

Starr replied with a mild amount of circumspection, but weighed in with a diagnosis of poliomyelitis:

The cases… would have all impressed me as cases of acute anterior poliomyelitis, without a doubt. The history does not appear to me to contradict this diagnosis, and while in some respects unusual … there is not as much difficulty in assigning them to anterior poliomyelitis as there is in assigning them to cerebo-spinal meningitis. Epidemics of anterior poliomyelitis are not unknown [though all prior reports were much smaller in magnitude].[57] (p. 675)

Dana replied more directly: “I can most positively state my opinion to be that your cases were mostly cases of anterior poliomyelitis” [56] (p. 5).

By November, Jacobi had received more detailed information on the cases from Starr (who had personally examined some of them); Jacobi then reconsidered his diagnosis, and to his credit revised his diagnosis to epidemic poliomyelitis [60].

With the input of his consultants, and in keeping with the growing consensus of medical opinion in the 1890s, Caverly initially concluded only that the disorder was an infectious disease that curiously had a low level of transmissibility:

It may be remarked that the microbic or infectious nature of the disease is generally believed in by us, whose opportunities for observing it have been merely clinical. … There is no evidence of its contagiousness, since it has affected almost invariably but a single member of a household.[56] (p. 5)

Caverly was initially unwilling to make a conclusive diagnosis of these cases and noted with obvious regret that, despite diligent efforts, no autopsies were obtained. Nevertheless, by his second report, he concluded that the epidemic was one of poliomyelitis:

[The] phenomena of this epidemic can be reconciled with a diagnosis of poliomyelitis. … A diagnosis of epidemic cerebro-spinal meningitis would certainly be more strained. The disease, cerebro-spinal meningitis, in epidemic form being more common, its symptoms and behavior are correspondingly better understood than poliomyelitis.[57] (p. 677)

With the facilitation of Caverly and surgeon Henry Haven Swift (1855–1926), Canadian pathologist [John] Andrew MacPhail (1864–1938), who was later knighted, studied records of a subset of 91 cases from this epidemic [59]. In this group, MacPhail found that 13% died, 32% did not improve, 30% improved partially, and 25% recovered fully. MacPhail could not see how fecal-oral transmission through the water supply could be possible, nor did it appear that the epidemic was vector-borne. Indeed, as Caverly had been, MacPhail was particularly struck by the physical separation of the cases:

It would be hard to discover a region in which a disorder had less license to become epidemic. The whole district in which these cases occurred lies upon a series of [mountainous] terraces, and increased safety did not come with elevation [which could potentially influence water-borne and vector-borne transmission]. Indeed, four cases occurred on the very ridge of the Green Mountains at an elevation of 1500 feet. The line of dwellings in which these patients lived extended over half a mile, and the water-supply was different in each of the four cases, namely, from springs out of the mountain.[59] (p. 623)

By the time of his final report on the 1894 epidemic, published in 1896, Caverly had identified 132 cases from that epidemic, of which there were 18 deaths (13.6%), a proportion very similar to that reported earlier (i.e., 13%) by MacPhail from a subset of the cases [58,59]. Caverly again revisited the issue of a possible infectious etiology for poliomyelitis, but he acknowledged that little progress had been made in establishing this as the etiology:

Thus far … there does not seem to have been any substantial progress made toward isolating any specific microorganism peculiar to this disease. Our epidemic with that of [Swedish pediatrician Karl Oscar] Medin [(1847–1927), who investigated an outbreak of 44 cases in 1887,] suggests, on purely clinical grounds, the possibility of such a cause.[58] (p. 5)

The issue of whether poliomyelitis was a form of epidemic cerebrospinal meningitis was revisited several times after the 1894 Vermont epidemic of poliomyelitis, but actual statistics that would support the clinical differentiation of these disorders had to await the formation of systematic surveillance systems for defined geographic areas, something that was only developing in some states after 1907.

5. Is Poliomyelitis a Bacterial Disease?

It was not long after the Vermont poliomyelitis epidemic (and, not coincidentally, shortly after the introduction of lumbar puncture) that bacterially contaminated spinal-fluid specimens were misinterpreted in patients with poliomyelitis [71,72,73,74]. German internist and surgeon Heinrich Irenaeus Quincke (1842–1922) had introduced the technique of lumbar puncture in 1891 [75], and, within a decade of Quincke’s report, bacteria were isolated from cerebrospinal fluid specimens, falsely suggesting bacteria as the causative agent of poliomyelitis. This was a time when numerous diseases (e.g., anthrax, tuberculosis, cholera, diphtheria, and typhoid fever) were found to be caused by bacteria, but before the first human disease was recognized to be caused by a filterable agent (i.e., yellow fever in 1901), so bacterial isolations were often assumed to be causal.

One of the first such mistakes was by Philadelphia neurologist Francis Xavier Dercum (1856–1931) (Figure 13), yet another protégé of S. Weir Mitchell [76], who on 23 October 1899, reported at a meeting of the Philadelphia Neurological Society that a diplococcus was observed in a Gram-stained specimen of spinal fluid from a two-year-old girl with poliomyelitis, although “Inoculations on glycerin agar and blood serum failed to show any growth after incubation for 48 h” [71] (p. 117). Dercum noted that Philadelphia neurosurgeon William Williams Keen (1837–1932) [77] had obtained the spinal fluid specimen by “Quincke puncture”.

Figure 13.

Philadelphia neurologist Francis Xavier Dercum (1856–1931). In 1899, Dercum presented a misleading report of diplococci on a Gram-stained specimen of cerebrospinal fluid obtained by Quincke puncture (lumbar puncture) from a two-year-old girl with poliomyelitis. Courtesy of the U.S. National Library of Medicine [78] (public domain).

Many similar (and similarly misleading) reports soon came from around the world [12,72,73,74]. For example, in 1908, while discussing results of the poliomyelitis epidemic in New York City in 1907, Starr noted that among 20 cases in which spinal fluid was obtained, 15 cases were bacteriologically sterile, whereas 5 (25%) grew several different bacteria species, suggesting that these were contaminants rather than causal microorganisms [12]:

In one a white staphylococcus grew; in one a Gram-positive bacillus and in three a large, Gram-positive coccus appeared in tetrads and pairs within large groups. … The coccus was looked on as a contamination.[12] (p. 113)

Until the viral nature of poliomyelitis was demonstrated in late 1909, though, numerous explanations (or excuses) were suggested for the failure to identify the presumed bacterial organism on microscopic examination of stained spinal fluid or in histological preparations. For example, as C.W. Duval noted in a presentation to the Louisiana State Medical Society in 1909 [79]:

Smear preparations [of cerebrospinal fluid] have always been negative except where the disease was superimposed by another infection, for example, pneumococcal, strepto[coccal], etc. All sorts of special media have been employed, both anaerobically and aerobically. The failure to find organisms in smears, even in most pronounced forms of the disease, does not signify much—certainly nothing against bacterial infection. The organisms may be ultra-microscopic, or require special methods of staining—who knows? Think of the years we have missed the syphilitic spirochete because of faulty technique. Now that we know how to stain for it the matter is extremely easy. Many organisms have been isolated in cases of acute anterior poliomyelitis, and called the excitors [sic] of the disease, but the opinions are too much at variance to place credence in any one of them.”.[79] (p. 747)

In 1909, physician-scientist Simon Flexner (1863–1946) (Figure 14), Director of the Rockefeller Institute for Medical Research in New York City, summarized his extensive but unsuccessful efforts to identify a bacterial basis for poliomyelitis in either spontaneous human cases or experimental poliomyelitis in monkeys [6,80]:

Figure 14.

Physician-scientist Simon Flexner (1863–1946), Director of the Rockefeller Institute for Medical Research in New York City. Flexner was the first director of the Rockefeller Institute for Medical Research in New York City, a position he held from 1901 until his retirement in 1935 (Rous 1949). In 1965, the Rockefeller Institute became Rockefeller University, a decade after it expanded its mission to include education. Photograph by Russian-born portrait photographer Elias Goldensky (1867–1943), Philadelphia. Reprinted from Ref. [81] (p. 5550).

We failed utterly to discover bacteria, either in film preparations or in cultures, that could account for the disease; and, since among our long series of propagations of the virus in monkeys not one animal showed, in the lesions, the cocci described by some previous investigators and we had failed to obtain any such bacteria from the human material studied by us, we felt that they could be excluded from consideration.[6] (p. 2095)

The following year, Flexner dismissed such reports of bacterial isolations from patients with poliomyelitis as nothing more than contaminants mistaken for an etiological agent:

Various bacteria, and especially certain cocci, have from time to time been isolated in cultures from fluids obtained by lumbar puncture from patients suffering from the epidemic disease [poliomyelitis], or from specimens of the central nervous system removed from victims at autopsy. These bacteria did not conform to one species or group of micro-organisms, and did not suffice to set up poliomyelitis in animals. They can be accounted for more satisfactorily as contaminations or secondarily invading bacteria than as the cause of the disease.[82] (p. 1106)

Flexner, one of the clearest and most foresighted thinkers of the period, was essentially dismissing these reports of bacterial isolation because they failed to meet Koch’s postulates to establish a necessary causal relationship between a microbe and a disease. The postulates were initially formulated as implicit or explicit steps for establishing a bacterial cause for disease by German microbiologists Robert Koch (1843–1910) and his protégé Friedrich Loeffler (1852–1915) in a variety of papers between 1878 and 1884, based in part on earlier concepts of German physician, pathologist, and anatomist Jakob Henle (1809–1885) in 1840, and these were subsequently refined and expanded by Koch in 1890 as follows [83,84,85,86,87,88,89,90,91,92]: (1) the microorganism must be invariably demonstrable in cases of the disease and must be absent in healthy individuals; (2) the microorganism can be isolated from the diseased host and grown in pure culture; (3) inoculation of a healthy, susceptible host (typically an experimental animal) with the pure culture must produce the disease; and (4) as specified by Koch, the microorganism must be re-isolated from the inoculated, diseased host and be identical to the original microorganism. Although these criteria could not always be fulfilled, even with bacterial diseases (e.g., if no susceptible experimental animal could be identified), these served as useful heuristics for establishing disease causation in many bacterial diseases.

Despite the experimental evidence and animal models supporting a viral etiology for poliomyelitis by 1909, some clinicians and clinician–scientists continued to believe that a bacterial cause would ultimately be demonstrated. Even as late as 1917, Edward C. Rosenow (1875–1966) (Figure 15) at the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minnesota, championed a “pleomorphic streptococcus or micrococcus” as the cause of poliomyelitis [93,94,95].

Figure 15.

Minnesota physician and bacteriologist Edward C. Rosenow (1875–1966) of the Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minnesota. Used with permission of the Mayo Foundation for Medical Education and Research, Rochester, Minnesota. Edited by Douglas J. Lanska, MD, MS, MSPH.

Given the early confusion over the clinical diagnosis between epidemics of (meningococcal) meningitis and poliomyelitis, expectations that similar bacterial organisms would ultimately be discovered in both conditions, and the undoubted limitations of the sterile technique in many of these early lumbar punctures, finding cocci in the smears and incorrectly concluding that they were the organisms responsible for the development of poliomyelitis is hardly surprising, and perhaps was to be expected.

6. More Extensive Field Studies Began Around 1907 in the US

In 1907, New York saw its largest epidemic of poliomyelitis to date, with approximately 2500 cases in the summer and autumn [96,97,98]. In October 1907, the New York Neurological Society appointed a seven-member committee of six neurologists and a psychiatrist to study the epidemic, including Chairman and neurologist Bernard Sachs (1858–1944) (Figure 16), neurologists James Ramsay Hunt (1872–1937), Smith Ely Jelliffe (1866–1945), Israel Strauss (1874–1955), Joseph F. Terriberry (1857–1932), and Edwin G. Zabriskie (1874–1959), and psychiatrist L. Pierce Clark (1870–1933). The Committee obtained the support of a committee appointed by the Section on Pediatrics of the New York Academy of Medicine [Linnaeus E. La Fetra (1868–1965), Herman Schwartz (1878–1945), and Louis C. Ager (1868–1944)], as well as the active cooperation of Simon Flexner at the Rockefeller Institute, Charles F. Bolduan (1873–1950) at the Department of Health of New York City, and orthopedic surgeon Henry L. Taylor (1857–1923). With these additions, the full Committee included 13 members.

Figure 16.

New York pediatric neurologist Bernard Sachs (1858–1944), circa 1900. Sachs chaired the Collective Investigation Committee, charged with studying the 1907 New York poliomyelitis epidemic [99] (public domain).

The Committee sent 4000 return postal cards to the physicians of Greater New York and the surrounding area, inquiring if they had seen any cases of infantile paralysis during the summer and autumn of 1907. Of 1100 answers received, 470 physicians reported seeing cases of infantile paralysis in that period. A detailed questionnaire was sent to those who reported seeing cases. This questionnaire included many details concerning the residence; prevalence of flies and mosquitoes and the presence of window screens; type of toilet (pit of flush basin); water supply (municipal, well, or rain-water cistern); number of cases in the family and their acquaintances; coincident illness in family members; pets in the house; travel out of town in the month preceding illness; gastrointestinal or respiratory disturbances preceding neurologic illness; typical diet, including raw milk consumption; symptoms in the first few days of illness, including fever, headache, muscle or joint pain, and respiratory, gastrointestinal, cutaneous, and neurologic symptoms; onset, progression, distribution, and severity of paralysis; disease course; results of laboratory studies if performed, including blood tests (white and red blood cell counts and hemoglobin), lumbar puncture (opening pressure and analysis results), and urinalysis; and results of autopsy if performed with attention to the gastrointestinal, respiratory, and central nervous systems and the presence or absence of lymphatic hyperplasia.

Considering the limitations of recognition and reporting, the Committee estimated that the 1907 New York epidemic involved about 2500 cases, although they had physician reports of only about 800 and data on 752 from their improvised reporting system. Unfortunately, the Committee’s report was not published until 1909 in abbreviated form and 1910 in the full form [96,97], by which time the results had been largely anticipated by a similar committee in Massachusetts, which published serial reports beginning in 1908, as well as by separate scientific investigations of some of its own members, particularly Flexner.

Coincident with the epidemic in New York, by autumn 1907 physicians in Massachusetts recognized many more cases of poliomyelitis than in previous years, so the Massachusetts State Board of Health launched an investigation into the distribution and characteristics of the disease, spearheaded by orthopedic surgeon Robert W. Lovett (Figure 17). In February 1908, the Board sent a circular letter to all the approximately 6000 physicians in the state “asking if in the year 1907 they had seen in their practice any cases of acute febrile disturbance in young children, followed by paralysis” [100] (p. 109). The Board subsequently sought details by a questionnaire for all physicians answering the initial inquiry with an affirmative answer. Through this process, the Board identified and analyzed 234 cases for 1907.

Figure 17.

Boston orthopedic surgeon Robert Williamson Lovett (1859–1924), professor of orthopedic surgery at Harvard, who was later famous as the physician who diagnosed Franklin Delano Roosevelt’s case of poliomyelitis in 1921. Reprinted from Ref. [101] (public domain).

The earliest states to require the reporting of cases of poliomyelitis were “chiefly, if not solely, in States where its prevalence has already alarmed the people” [98]. For example, poliomyelitis became a reportable disease in November 1909 in Massachusetts and in 1910 in New York. Massachusetts subsequently emphasized the importance of reporting by declaring poliomyelitis “dangerous to public health” (along with trachoma and ophthalmia neonatorum) [102]. New York neurologist Joseph Collins (1866–1950) made a “plea that it may be considered a reportable quarantinable disease” [103,104]. However, there was not a national reporting system at this time, and hence no requirement for reporting polio cases at a national level (it was not until 1951 that the Centers for Disease Control implemented a national morbidity reporting system and polio became a “reportable” disease, meaning it was required to be reported to public health authorities).

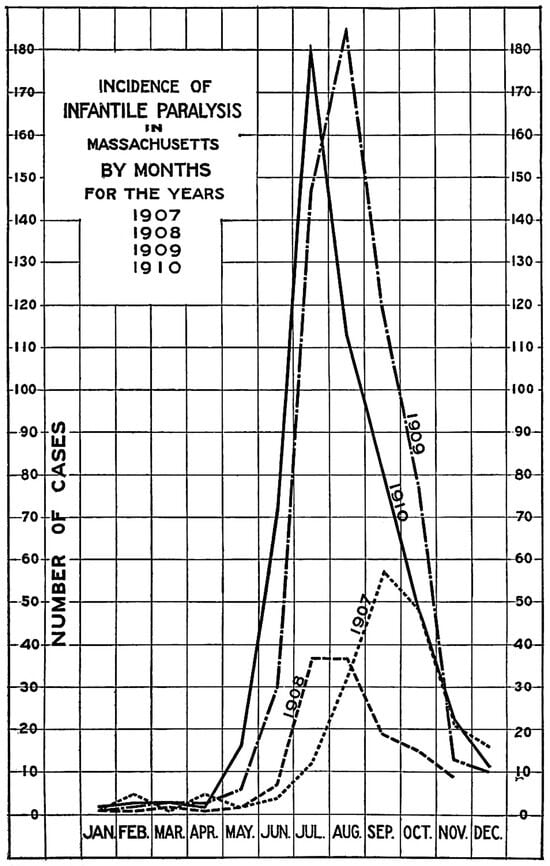

By around 1910, there were several reports from state-level surveillance, such as the report of poliomyelitis cases in Massachusetts in 1909 (presented in graphic form only) by Lovett (619 cases) [55,105,106,107,108]. The considerably increased sharpness of the seasonal peak for the 1909 poliomyelitis data [i.e., the tallest curve in Figure 6] likely reflects, at least in part, a difference in the approach to case ascertainment between that study and prior cases series collected over multiple years that incorporated non-epidemic data (which would tend to flatten such curves) [40,49,50,51,52,53].

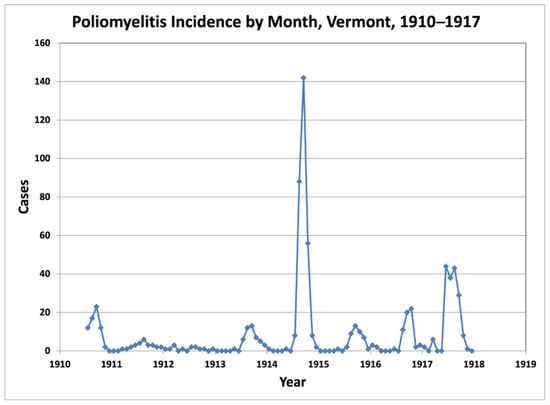

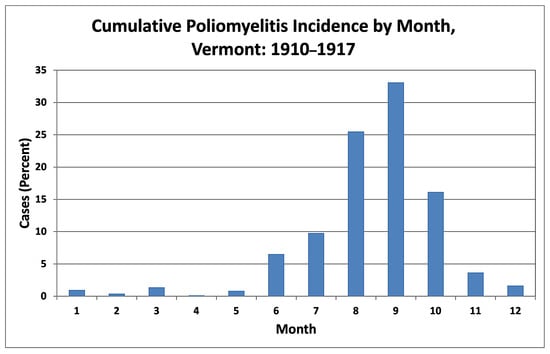

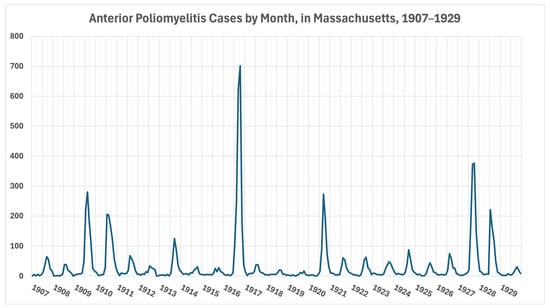

With the increased availability of state surveillance data for poliomyelitis from around 1910, the clear seasonal pattern of poliomyelitis, with varying magnitudes of epidemics from year to year in the same broad geographic territory, became apparent, as shown, for example, by data collected by Lovett and Mark W. Richardson for Massachusetts for 1907–1910 (Figure 18) and then extended to 1912 by Richardson, by Caverly for Vermont from 1910 to 1917 (Figure 19 and Figure 20), and then by Filip C. Fursbeck and Eliot H. Luther at the Rockefeller Institute for Medical Research for Massachusetts from 1907 to 1929 [62,109,110,111,112,113,114,115] (Figure 21 and Figure 22). By this point, poliomyelitis was well established as an unwelcome, though fairly predictable, scourge of late summer and early fall. Epidemics often began in June or July, after which the number of cases increased greatly at the end of summer. One third of all cases occurred in September, and three quarters occurred in the three months with the highest number of cases, i.e., from August to October.

Figure 18.

Seasonal variation in poliomyelitis incidence for Massachusetts by month for each year from 1907 to 1910. Reprinted from Ref. [111] (public domain).

Figure 19.

Time series of incident poliomyelitis cases for Vermont from June 1910 through 1917. Data from Ref. [62].

Figure 20.

Seasonal variation in poliomyelitis incidence for Vermont from 1910 to 1917. Data from Ref. [62].

Figure 21.

Time series of seasonal variation in poliomyelitis incidence for Massachusetts by month from 1907 to 1929. Data from Ref. [115].

Figure 22.

Seasonal variation in poliomyelitis incidence for Massachusetts for 1907–1929. Data from Ref. [115].

In 1908, orthopedic surgeon Robert Lovett, on behalf of the Massachusetts State Board of Health, compared the month of onset for 412 cases of cerebrospinal meningitis and “234” cases of infantile paralysis [Note: although there were 234 cases of poliomyelitis reported, the month of onset was plotted for only about 208 of these, presumably because of missing or imprecise month-of-onset data for the unplotted cases] [102]. The resulting curves are almost perfectly out of phase with each other, so that the incidence of cerebrospinal meningitis started rising in February, peaked in April, and declined back to baseline by July, whereas the incidence of poliomyelitis began rising in July, peaked in September, and declined back to baseline by January [105,114] (Figure 23). Bacterial meningitis does indeed have a seasonal pattern, peaking in the winter months in countries in both the northern and southern hemispheres, a pattern which is distinctly different from the characteristic peak of poliomyelitis in the late summer and early fall [116].

Figure 23.

Comparison of seasonal incidence of cerebrospinal meningitis with that of poliomyelitis in Massachusetts for 1907. Reprinted from Refs. [106,114] (public domain).

In 1910, Fritz Lange (1864–1952), a German orthopedic surgeon and Professor of Surgery at the University of Munich, visited orthopedic facilities in the northeastern United States. Lange was particularly impressed with Lovett and his work with spinal biomechanics and his pioneering studies of poliomyelitis in Massachusetts:

Above all I would single out the extensively planned and very carefully conducted investigation of Lovett on the spread of poliomyelitis in Massachusetts. With the support of the state, which allocated 40,000 Mark [i.e., approximately $10,000 in 1911 dollars] for this study in 1911, he was able to investigate the source of infection for every single case, and based on the preliminary results we can expect a fundamental, classical study comparable to the works of [Swedish physicians Karl Oscar] Medin and [Ivar] Wickmann.[117] (translation p. 285)

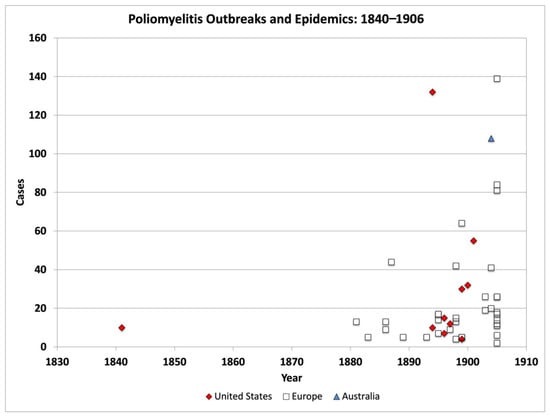

7. Systematic Syntheses of Prior Polio Epidemics to 1910

By 1908, sufficient reports of poliomyelitis outbreaks and epidemics had accumulated in the global literature for systematic syntheses to be completed [11,118]. Eminent New York pediatrician Luther Emmett Holt (1855–1924) [119] (Figure 24), Professor of Diseases of Children in the College of Physicians and Surgeons of Columbia University, along with pediatric colleague Frederic Henry Bartlett (1875–1948), collected data from 35 epidemics, beginning with the small outbreak in Feliciana, Louisiana (about 10 cases in 1841) reported by Colmer in 1843, and extending through later epidemics: Stockholm, Sweden (44 cases in 1887), reported by Medin in 1890; Rutland, Vermont (132 cases in 1894), reported by Cavery; Brisbane, Australia (108 cases in 1904); and Drontheim, Norway (139 cases in 1905) [11,120] (Figure 25). As determined by a systematic review of polio epidemics itemized in A Bibliography of Infantile Paralysis: 1789–1944 [1], and by review of the data sources for several subsequent systematic syntheses, the original study by Holt and Bartlett was remarkably complete [12,18,103,121]. These additional data sources added only a few small outbreaks to the work of Holt and Brown, but did extend the period to 1910, by which time poliomyelitis had been shown to be a viral disease.

Figure 24.

New York pediatrician Luther Emmett Holt (1855–1924). In 1908, with colleague Frederic Henry Bartlett, Holt presented a systematic synthesis of prior poliomyelitis outbreaks and epidemics to 1906. The analysis of Holt and Bartlett of data for these epidemics strongly supported an infectious etiology for poliomyelitis. Courtesy of the National Library of Medicine, Bethesda, Maryland [122] (public domain).

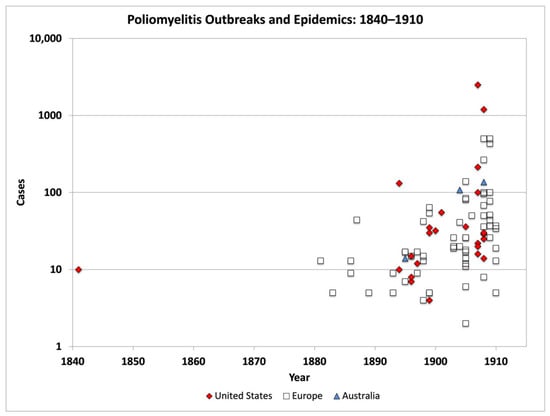

Figure 25.

Outbreaks and epidemics of poliomyelitis in the United States, Europe, and Australia from 1840 to 1906 as summarized in 1908 by New York pediatricians Luther Emmett Holt (1855–1924) and Frederic Henry Bartlett (1875–1924). Data from Ref. [11].

Holt and Bartlett acknowledged that,

The epidemics are widely separated both in time and location, and the records of many of them are very meager. In fact, few of them have been reported with a degree of care which makes a detailed study of them of great value, although collectively they throw considerable light upon the disease.[10] (p. 648)

Most of the outbreaks were very small until the last decade of the 19th century. Indeed, prior to 1890, all the outbreaks involved fewer than 20 cases, except for the small epidemic of 44 cases in Stockholm in 1887. It was at this point that reports mushroomed around the world, with epidemics of increasing magnitude, with the largest three exceeding 100 cases. Even these early outbreaks were soon to be dwarfed by much larger outbreaks of more than 1000 cases, e.g., in New York in 1907 (an estimated 2500 cases) and especially in 1916 [96,97,123,124,125,126,127].

Holt and Bartlett recognized that most of the outbreaks were very small, and even in larger epidemics the cases were often geographically disbursed: “The comparatively small number and wide [geographic] distribution of the cases in most of the epidemics is very striking, and seems to indicate that the different cases had no relation to one another or to a common cause [i.e., common source]” [11] (p. 652). However, as an offset to this information, they developed separate lines of evidence that “point quite definitely to a connection between different cases, indicating either a communication of the disease from one person to another, or the development of several cases near together from a common cause [i.e., common source]” [11] (p. 652). For example, they identified 40 instances, collectively comprising 96 cases, in which more than one case occurred in a family or household. In 29 of these 40 instances, a definite attack interval was given for cases within a household that ranged from 0 to 8 days in 28, with an outlier at 6 weeks. In 10 additional instances, a range was given that addressed multiple secondary cases within a household or was simply vague or imprecise. Such secondary cases suggested either a range of incubation periods following a common source of exposure, a continuing source outbreak (i.e., resulting from an exposure which persisted over an extended period), or secondary transmission within the household. They noted other instances where a child developed poliomyelitis shortly after moving into an infected district, or shortly after leaving it.

This synthesis strongly reinforced the seasonal nature of poliomyelitis outbreaks, with epidemics uniformly occurring in the summer and terminating with the onset of colder weather:

In 33 [of the 35 studied outbreaks and epidemics, or 94%] it is definitely stated that the epidemic occurred during the hot season only, or summer and early autumn, the most frequent months being July, August, and September. In almost every instance the epidemic terminated with the month of October. In one Australian epidemic [i.e., in Brisbane, 1904] the months of occurrence were March and April, which correspond to October and November [sic, September and October] in our climate.[11] (p. 649)

Holt and Bartlett found little to support the idea that sporadic cases might be increased in a community following an outbreak or epidemic of poliomyelitis. Instead, “after several of the epidemics … including some of the larger ones … in succeeding years … no cases were observed” [11] (p. 649). Norway’s experience of major annual epidemics in the early 20th century might have appeared to be a major exception. However, Holt and Bartlett noted that, “In Norway, although successive epidemics were reported in the years 1903, 1904, and 1905, it does not appear, from the reports, that the same communities were attacked” [11] (p. 640). Holt and Bartlett did not appreciate the significance of this observation, but they were clearly describing herd immunity.

Holt and Bartlett reported 201 deaths among 1659 collective cases, totaling a collective case-fatality rate of 12.1% [11]. However, in calculating mortality, Holt and Bartlett included epidemic and non-epidemic cases for Norway for the period 1903–1906, when Norway was establishing a national surveillance system. The collective cases for Norway in that interval (n = 1132) represent more than 2/3 of the cases reported in all the outbreaks and epidemics in the world literature to that point. When only city-level and regional epidemics are considered, there were 123 deaths recorded among 1039 cases, giving a short-term case-fatality rate of 11.8%, which is still very similar to the value reported by Holt and Bartlett.

Holt and Bartlett concluded that this epidemic pattern strongly supported an infectious etiology for poliomyelitis. When this was coupled with reports of secondary cases occurring within a household, they considered this conclusion nearly unassailable.

The occurrence of epidemics and the relation of certain groups of cases to one another in these epidemics place beyond question the statement that acute poliomyelitis is an infectious disease. Whether we can go farther and state that the disease is communicable is an open question. After carefully considering all the evidence…, we cannot resist the conclusion that the disease is communicable, although only to a very slight degree, one of the most striking facts being the development of the second cases within ten days after possible exposure. Positive statements, however, must be deferred until the discovery of the infectious agent.[11] (p. 662)

Several issues complicated attempts at systematic syntheses in this era: (1) many clinicians had difficulty distinguishing poliomyelitis from other causes of childhood (or later age) paralysis on clinical grounds and there were no accurate diagnostic tests to establish the diagnosis; (2) in general, this was prior to organized public health surveillance and reporting programs, and prior to requirements for mandatory notification of epidemic diseases; (3) in the first decade of the 20th century, as public health surveillance systems were beginning in some U.S. states and some countries (e.g., Norway), these systems collected sporadic cases with epidemic cases over broader geographic areas, producing larger estimates of poliomyelitis incidence that were nevertheless distorted estimates of the size of “epidemics”; and (4) there was little appreciation of the possibility of infectious non-paralytic cases or carriers, and tentative appreciation of this issue was only beginning by the very end of this period. When public health surveillance systems began to be developed in some countries and localities, case recognition and reporting increased significantly, and non-epidemic sporadic cases were included that otherwise would have not been tallied and would certainly not have been separately reported [128]. Notification of poliomyelitis became mandatory in Norway in 1905, and in various provinces of Austria and Germany by 1909 [128]. In 1907, Massachusetts became the first U.S. state to institute mandatory notification of all cases of poliomyelitis, and in 1910 the Surgeon General of the Public Health Service requested that all states submit reports on poliomyelitis for 1909 and 1910, but it was not until 1922, following the unprecedented devastating poliomyelitis epidemic of 1916, that all states regularly participated in a national morbidity reporting system for poliomyelitis [129,130]. A significant increase in reporting (and increased interstudy variability) occurred when non-paralytic cases began to be increasingly recognized and variably included.

To consider the expanding size of polio epidemics from 1840 to 1910, only reports of outbreaks and epidemics from cities are included to avoid distortions caused by including sporadic cases from non-epidemic areas in the totals of “epidemics” [11,12,18,103,121] (Figure 26). Specifically, annual poliomyelitis totals from state-level and national-level reporting are excluded. Consequently, the annual tabulations for Norway for 1903 to 1906 from the tabulations of Holt and Bartlett (1908) were not included, nor were the results for individual U.S. states from 1907 to 1910, the collected results for reporting states in the United States in 1910, or the results for states of other countries from 1907 [11,18,103,121]. The early outbreak of approximately ten cases in 1841 in Louisiana remained without parallel until the 1880s, whereas epidemics of more than 100 cases were not achieved until the 1890s, those of more than 1000 cases until the 1900s, and those of more than 10,000 cases (i.e., in New York City in 1916, not shown) until the 1910s (Table 1). The case fatality from the collected studies in the era from 1840 to 1910, in which this data was reported, was 9.1% for the United States (32 deaths from 350 cases) and 10.6% worldwide (188 deaths from among 1772 cases).

Figure 26.

Semi-log plot of outbreaks and epidemics of poliomyelitis in the United States, Europe, and Australia from 1840 to 1910. A semi-log pot is necessary because the sizes of the outbreaks and epidemics spanned more than three orders of magnitude. Plot by Douglas J. Lanska, MD, MS, MSPH. Data from Refs. [11,12,18,103,121].

Table 1.

Poliomyelitis cases in reported outbreaks and epidemics 1880–1909. Data from Refs. [11,12,18,103,121].

8. The Shifting Age Distribution of Cases (1840–1910)

Initially poliomyelitis affected almost exclusively infants and very young children. This was, of course, implied by the early name for the disease, infantile paralysis, as well as variably precise variants of this term, such as infantile spinal paralysis, essential paralysis of childhood, atrophic infantile paralysis, and atrophic paralysis of childhood.

Beginning in the 1870s, cases of spinal paralysis resembling “infantile paralysis” were increasingly reported in adults, with multiple authors suggesting that the adult cases were, in fact, caused by the same disease, albeit with an atypical onset age [131,132,133,134,135,136,137,138,139,140]. By 1911, pioneering epidemiologist Wade Hampton Frost (1880–1938) (Figure 27), then Passed Assistant Surgeon of the United States Public Health and Marine Hospital Service, argued that “The term ‘infantile paralysis’ is objectionable, because it is hardly applicable to adult cases; also, because it is likely to be confused with other infantile paralyses of altogether different etiology” [16] (p. 6). Furthermore, Frost noted that the Bureau of the Census had attempted to tally mortality statistics for poliomyelitis in 1909, but experienced considerable difficulty because the disease was reported under 24 different designations. Consequently, the Bureau of the Census urged the uniform adoption of the term “acute anterior poliomyelitis” [16].

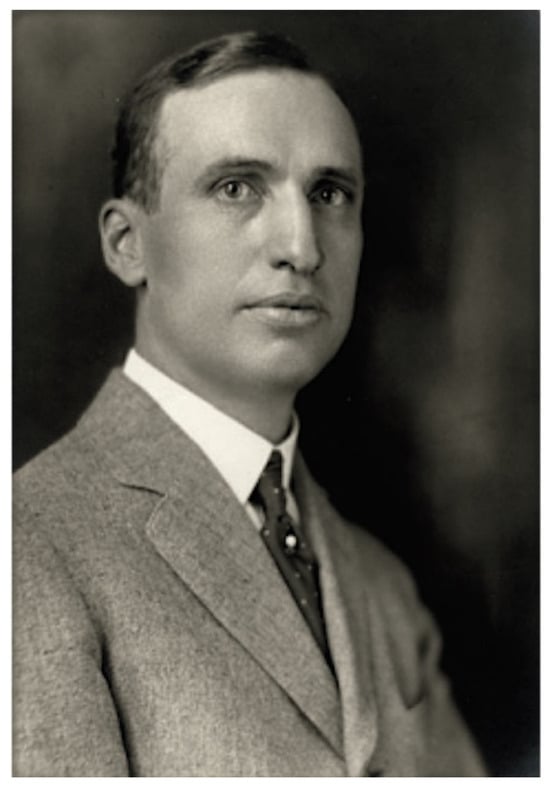

Figure 27.

Epidemiologist Wade Hampton Frost (1880–1938), Passed Assistant Surgeon of the United States Public Health and Marine Hospital Service [141]. Used with the permission of Bachrach Photography, the oldest continuously operating photo studio in the world, with locations in Philadelphia, New York, Boston, and Washington, D.C.

Assessing the age distribution of cases of poliomyelitis in outbreaks and epidemics in the interval from 1840 to 1910 is difficult. Authors were typically vague about the ages of affected cases, and when some age information was presented, it was often in arbitrary ranges of unequal size, with a large proportion of cases without reported ages, with ages presented in a wide range, and with age intervals that were not specified precisely or that even overlapped. For example, in the Rutland, Vermont, epidemic in 1894, Caverly reported 85 cases under 6 years, 21 cases from 6 to 14 years, and 7 cases “between a few months and 9 years” [58]. Data are sufficient to show, for the outbreaks and small epidemics of the mid to late 19th century and the first decade of the 20th century, that the median age of cases was consistently less than 5 years of age [8,16,42,51,52,55,58,96,97,108,142,143,144]. Adequate age-specific information was uncommon until the very end of this interval [52,55,108,145] (Figure 28).

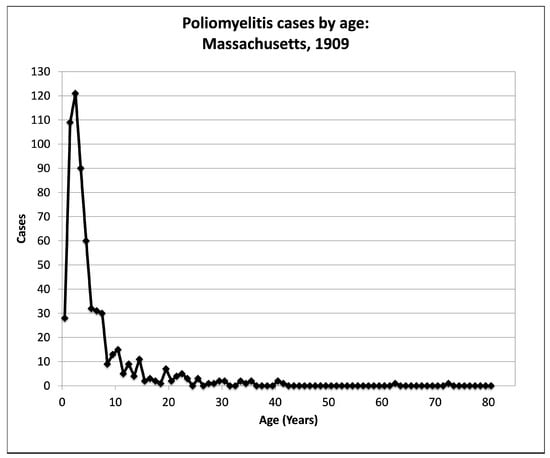

Figure 28.

Age distribution of 615 incident poliomyelitis cases in Massachusetts in 1909. Data from Refs. [55,108].

Field epidemiology was rare before 1900. Starr went to see cases in the Rutland, Vermont, epidemic of 1894, but this was mostly to establish the correct diagnosis of the responsible disorder. The pioneers of polio field epidemiology were Swedish physician Otto Ivar Wickman in Norway in 1905 [146,147], and, subsequently, Massachusetts State Inspector of Health Herbert Clark Emerson (1865–1922), Minnesota state epidemiologist Hibbert Winslow Hill (1871–1947), Massachusetts State Board of Health “Special Investigators” Sheppard and Hennelly (a fourth-year medical student at Harvard Medical School and a recently graduated physician from Harvard Medical School, respectively), and finally Wade Hampton Frost for the U.S. Public Health and Marine-Hospital Service [16,55,108,144,145,148,149,150,151,152,153]. Of these, Wickman and Frost made the most substantial contributions. From 1910 to 1912, Frost investigated six outbreaks of poliomyelitis, with a total of 475 paralytic cases and 54 “abortive” cases that failed to develop central nervous system manifestations. In 1911, John Anderson and Frost experimentally demonstrated the presence of specific anti-poliovirus antibodies in the serum of abortive (non-paralytic) cases of poliomyelitis [154], but this did not immediately lead to a laboratory test, and for some time clinicians had no accurate means of identifying cases of poliomyelitis in the absence of an acute paralytic syndrome [155]. Frost noted that, “The spontaneous decline of epidemics in localities where only a small percentage of people have been attacked, and the subsequent immunity of these localities while the epidemic spread in contiguous localities suggests that a population may be immunized by an epidemic giving rise to only one recognized case among several hundred or several thousand inhabitants” [145] (p. 251).

The data for poliomyelitis incidence in Massachusetts for 1909 were categorized into single years of age. Graphing these data shows a highly skewed distribution with a long tail: two thirds of cases were under 5 years of age, and 85% were under ten years of age, but the oldest case was 72 years (Figure 28). Interestingly, the maximum number of incident cases occurred in those from 1 to 4 years of age, whereas infants were relatively spared, a fact unappreciated at the time, but reflecting naturally acquired passive immunity conveyed from the mother to the infant either transplacentally or through breast feeding.

Systematic surveillance of poliomyelitis incidence for defined geographic regions was only beginning over the interval from 1905 to 1910. Available data are insufficient to adequately assess whether there was a shift in the age distribution of incident cases of poliomyelitis over the interval from 1840 to 1910, although available information suggests that poliomyelitis was, at least initially, limited to young children during the mid-19th century until adult cases were recognized and increasingly reported, beginning in the 1870s.

The distribution of population immunity was not considered as an explanation for the shifting age distribution of poliomyelitis epidemics until 1918, when this was suggested as a possibility by Claude Hervey Lavinder (1872–1950) of the U.S. Public Health Service [125] (Figure 29):

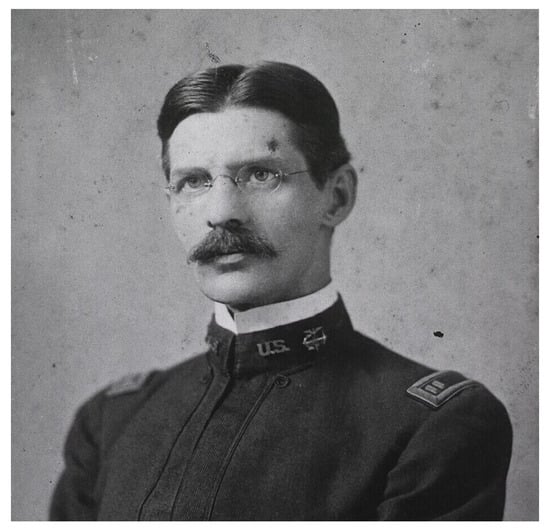

Figure 29.

Assistant surgeon Claude Hervey Lavinder (1872–1950) of the U.S. Public Health Service in 1898. Courtesy of the National Library of Medicine, Bethesda, Maryland. Adapted from [156] (public domain).

The rapid spread of epidemics over wide areas, their spontaneous decline after only a small proportion of the inhabitants have been attacked, and, above all, the preponderating incidence in young children, have not been satisfactorily explained by any hypothesis other than that the infective agent, during epidemics, is widespread, reaching a large proportion of the population, but only occasionally finding a susceptible individual, usually a young person, in whom it produces characteristic morbid effects. … As to what constitutes susceptibility or the converse—immunity—practically nothing can be deduced except that age is obviously a factor of importance, susceptibility being generally greatest in the first half decade of life, thereafter progressively diminishing until in adult life there is a very general immunity to natural infection. … Conceivably the greater immunity of adults may be due to a nonspecific resistance, developing naturally with maturity, without reference to previous exposure to or infection with the specific virus of poliomyelitis. On the other hand, there are certain facts which suggest that the very general immunity of adults may be specific, acquired from previous unrecognized infection with the virus of poliomyelitis.[125] (pp. 22–23)

This explanation, involving the shifting distribution of population immunity, had to await recognition of the development of immunity in previously exposed individuals by physician-scientist Simon Flexner and pathologist Paul A. Lewis (1879–1929) at the Rockefeller Institute for Medical Research in 1910 [82,157,158,159], the development of adequate population surveillance systems after 1905, and the collection of adequate longitudinal population data [125].

9. Is Poliomyelitis Infectious and Contagious? Perspectives from 1890 to 1905

In the early 1890s, few were even considering the possibility that poliomyelitis was an infectious disease. In 1892, in his Text-Book of Nervous Diseases, New York neurologist Charles Loomis Dana concluded that “age, season, and infectious diseases are the three most important etiologic factors” for poliomyelitis [37] (p. 221, original emphasis). This was in large part based on the widely acknowledged predilection for the disease to affect young children, the seasonality reported by Sinkler in 1875, and Sinkler’s recognition that infectious fevers often preceded the paralytic attack [36,37].

In 1893, Boston neurologists James J. Putnam and Edward Wyllys Taylor further considered evidence for an infectious etiology for poliomyelitis, in an astute but cautious analysis:

To what is the unfavorable influence of the summer due? It may be an affair of weather, as such, though obviously heat, pure and simple, is not the important factor; or the weather may act as favoring some other influence, perhaps bacterial in character. The reasonableness of this latter view is now conceded by many good observers: but it is certain that its advocates are still far from having made good their claim. In favor of the doctrine [of an infectious etiology] is the fact that the outbreaks of the disease occasionally occur in distinct epidemics. These so-called epidemics, however, have always happened in late summer and early autumn…[38] (p. 510)

In contrast to other recognized epidemic diseases of the time, however, such as smallpox and measles, poliomyelitis did not have a marked propensity for direct contagion, such as among family members. As Putnam and Taylor noted, “It is noteworthy, as against any strongly marked epidemic influence, that the patients did not come to any extent, from any one locality, but from different parts of the large area of the suburbs of Boston” [38] (p. 510).

As part of the Mutter Course of Lectures delivered before the College of Physicians of Philadelphia in 1893, Philadelphia surgeon DeForest P. Willard (1846–1910) (Figure 30), the first Chairman of the Department of Orthopaedic Surgery at the University of Pennsylvania, and Philadelphia neurologist of Guy Hinsdale (1858–1948) (Figure 31), another protégé of S. Weir Mitchell and also of Canadian-American internist William Osler (1848–1919), were among others who suspected that poliomyelitis was an infectious disease [160,161,162]. They too were quite objective in their assessment and recognized that this was not yet proven.

Figure 30.

Philadelphia orthopedic surgeon DeForest P. Willard (1846–1910), the first Chairman of the Department of Orthopaedic Surgery at the University of Pennsylvania. In 1893, with colleague Guy Hinsdale, Willard proposed, in the Mutter Course of Lectures delivered before the College of Physicians of Philadelphia, that poliomyelitis is an infectious disease. Courtesy of the National Library of Medicine, Bethesda, Maryland [163] (public domain).

Figure 31.

Philadelphia neurologist Guy Hinsdale (1858–1948). Courtesy of the National Library of Medicine, Bethesda, Maryland [164] (public domain).

It is probable that anterior poliomyelitis will be relegated in the near future, in common with many other diseases of the nerve-centres, to the class of infectious diseases of microbic origin. As yet we have little proof to offer in support of such a proposition, but the surgical pathology of today is nothing if not bacterial.[160] (p. 68)

The mid- to late-19th century was, of course, the time when the germ theory of disease was being developed in Europe by Hungarian obstetrician Igaz Semmelweis (1818–1865) in the 1840s, English physician and epidemiologist John Snow (1813–1858) in the 1850s, French microbiologist Louis Pasteur (1822–1895) in the 1860s–1870s, and German microbiologist Robert Koch (1843–1910) in the 1870s. Investigators came to consider many conditions as bacterial, often simply because the paradigm had proven so successful. Willard and Hinsdale put polio in this context:

One affection after another is analyzed in the laboratories of the world; the organism is finally isolated by the refinement and higher powers of the pathological technique of these last years of the century. In these days we could fill a veritable Pandora’s box with the scourges of the universe, the pure cultures would be marked with the names of anthrax and tubercle, relapsing fever and glanders, cholera and typhoid, diphtheria and leprosy, pneumonia and tetanus; with the names of Neisser and Lavern and Pasteur, and with all the toxins and ptomaines in an ever-lengthening list. The plagues that have escaped to the ends of the earth are now collected within the walls of our modern institutes of hygiene. … With regard to poliomyelitis the evidence as yet is meager.[160] (p. 68)

In 1905, after a large polio epidemic in Sweden, Swedish physician (Otto) Ivar Wickman (1872–1914) provided substantial evidence that polio was a contagious disease, with at least some cases being abortive (non-paralytic) cases that were nevertheless still important as sources of further transmission of the disease [146,147,148,165]. Although Wickman was not the first to suggest that abortive cases could serve as important sources of further transmission of the disease, his work helped convince many researchers that this was the case [82,148]. As Simon Flexner (1863–1946) at the Rockefeller Institute for Medical Research in New York City noted:

[D]ata collected in Scandinavia indicate that the contagion can be carried by intermediate persons from the stricken to the healthy, and from patients not frankly paralyzed, but suffering with slight or so-called abortive attacks of the disease. Moreover, the incubation period of the disease would appear to vary within considerable limits, being sometimes not more than two or three or four days in length and at other times as much as twenty days, the average being eight or ten days…[82] (p. 1106)

10. Proof That Poliomyelitis Is an Infectious Viral Disease

As early as 1907, Flexner had attempted to transmit poliomyelitis from humans to monkeys during the 1907 poliomyelitis epidemic in New York City, but the attempt failed for various technical reasons (as was evident in retrospect).

[I]n 1907, when the first epidemic appeared in New York [City] and vicinity, we endeavored to transfer poliomyelitis from human beings to monkeys. Unfortunately we were at this time limited merely to fluids obtained by lumbar puncture from cases at different stages of the disease. I say unfortunately for the reason that we had the idea originally of bringing the supposedly infected material directly into relation with the nervous systems of monkeys. This we indeed did with the fluids obtained by lumbar puncture, from which we failed entirely lo produce any symptoms that we could discover, including paralysis. During the epidemic of 1907 we did not secure organs from a case of pure infantile paralysis, and we failed, therefore, in our intention to inoculate monkeys from the spinal cord.[82] (p. 1106)

In the summer of 1909, Austrian pathologist Karl Landsteiner (1868–1943), then prosector at the Royal-Imperial Wilhelminen Hospital in Vienna, along with his assistant, German pathologist Erwin Popper (1879–1955), demonstrated that poliomyelitis could be transmitted to monkeys, apparently by a virus [5,82,148,166,167]. Landsteiner and Popper had obtained virulent spinal cord tissue from a 9-year-old boy who died of poliomyelitis, then ground it up and filtered a suspension of this material through a very dense porcelain filter (Chamberland-Pasteur filter), with pores so minute that they precluded the passage of bacteria. Using this bacteriologically sterile filtrate, Landsteiner and Popper nevertheless produced signs of paralysis in a rhesus monkey (Macaca mulatta) and a baboon (Cynocephalus hamadryas) after intraperitoneal injection of this filtrate, and the histology of the spinal cord from these New World primates was identical to that of human poliomyelitis, proving that poliomyelitis is a viral disease. However, as Flexner noted, “in endeavoring to continue the transfer of the virus by intraperitoneal injection of other monkeys they failed entirely” [82] (p. 1107). In the late summer or early autumn of 1909, Israel Strauss (1873–1955) and Frank Huntoon (1881–1948), at Cornell Medical College in New York City, were similarly able to transmit poliomyelitis from humans to monkeys but were unable to transmit it serially between monkeys [82,168,169].

By September 1909, these prior results were confirmed and expanded by Flexner and Paul Aldin Lewis (1879–1929) at the Rockefeller Institute [82,170,171,172,173] (Figure 32). Unlike prior investigators, Flexner and Lewis successfully demonstrated both the creation of experimental poliomyelitis in monkeys through the intracerebral injection of infected human nervous tissue and the successful transmission of experimental poliomyelitis from one monkey to another [82,170,171,172]. As Flexner recounted,

Figure 32.

Physician-scientist Simon Flexner (1863–1946), Director of the Rockefeller Institute for Medical Research in New York City, in his laboratory, circa 1912. Reprinted from Ref. [174] (public domain).

It was not until September, 1909, that we secured the spinal cord from two cases of infantile paralysis in human beings, which specimens were employed for the inoculation of monkeys by direct injection of an emulsion into the brain through a trephine opening. The first inoculations were successful. The animals immediately after their recovery from the ether anesthesia were lively and normal. They remained apparently in perfect health for a number of days, when paralysis set in. The spinal cord derived from these animals was and is still being employed to transmit the infection to still other monkeys.[82] (pp. 1106–1107)

Flexner and Lewis demonstrated that the infectious agent was a “minute and filterable virus that have not thus far been demonstrated with certainty under the microscope” because it could pass a Berkefeld filter made of diatomaceous earth that could exclude all known bacteria [6] (p. 2095), [175]. They also showed that germicidal substances—later known as neutralizing antibodies—were present in the blood of monkeys that had survived poliomyelitis [6]. Flexner subsequently extended his studies of experimental poliomyelitis with Lewis and various other colleagues [158,159,176,177,178,179,180,181,182,183,184,185].

11. Persisting Questions Concerning the Contagiousness of Poliomyelitis

The studies of experimental poliomyelitis in monkeys surprised many but nevertheless convinced most that poliomyelitis was an infectious disease, even if serious questions remained regarding its contagiousness and method of transmission. At a meeting of the Medical Society of the County of New York on October 24, 1910, Simon Flexner presented a paper on “The relation of experimental to human poliomyelitis” [157]. In the discussion, New York pediatrician Luther Emmet Holt (1855–1924) said,

Even five years ago if anyone had suggested that the disease under discussion was an infectious or a contagious one, it would have been looked upon as a joke. The opportunity for studying the disease during the past few years had been so great that it was now a settled question that the disease was spread from patient to patient.[157] (pp. 925–926)

Nevertheless, doubts about the contagiousness of poliomyelitis persisted well into the 20th century, in part because the fecal-oral mechanism of transmission was not understood, and there was little recognition of the importance of non-paralytic cases, asymptomatic carriers, and resistant (immune) individuals, much less an accurate clinical or laboratory means of identifying such disease groups. As noted by public health physician Frank George Boudreau (1886–1970) and colleagues, from the Ohio State Board of Health, as late as 1914, five years after poliomyelitis was demonstrated to be a viral disease, many (and possibly most) clinicians still doubted the contagiousness of poliomyelitis [186]. Boudreau was a thoughtful observer and synthesizer, who would later serve as Director for the League of Nations Health Section, Chairman of the Food and Nutrition Board of the National Research Council, and head of the United States Committee for the World Health Organization. Factors Boudreau saw as hampering the wide recognition of the contagiousness of poliomyelitis included an erroneous expectation that an infectious disease should routinely affect multiple members of a family (which was not the case with poliomyelitis), and a failure to appreciate the high frequency of non-paralytic cases and resistant (immune) individuals:

The view that acute poliomyelitis is contagious has been gradually gaining ground among those most familiar with the disease, although the large mass of clinicians who see only isolated and sporadic cases are still unconvinced. It has been pointed out by the opponents of this theory that the percentage of second cases in a family is small, but this argument can be met with two statements,—first, that many abortive cases of acute poliomyelitis occur and are not recognized, and, second, many individuals are not susceptible to acute poliomyelitis and many other transmissible diseases with the exception of smallpox and measles, which flourish in any soil. … In acute poliomyelitis, as in epidemic cerebro-spinal meningitis, many people—a large majority of the population, appear to be insusceptible. A further reason why the contagious nature of acute poliomyelitis cannot be disproved is that we do not know how numerous are healthy carriers and missed and abortive cases.[186] (pp. 8–9)

Even as late as 1918, Claude Hervey Lavinder of the U.S. Public Health Service expressed continued concerns about the lack of adequate epidemiological support for the person-to-person transmission of poliomyelitis [125]:

The dominant view that poliomyelitis is a contagious disease spread directly from person to person does not receive, on the surface at least, adequate support from the epidemiologic evidence which is ordinarily sought to establish such a conception, namely, the incidence of cases among persons known to have been intimately associated with the sick, and the establishment among those sick of some previous association with other cases of the disease. In other words, we can not show any undue prevalence of the disease among the persons surrounding the patient, nor can we trace satisfactory connection between one case and other previous case.[125] (p. 21)