Personal Development of Doctoral Students

Definition

1. Introduction

2. Personal Development

3. Frameworks for Personal Development

4. Supervision and Personal Development

5. Coaching and Personal Development

A Designed and Non-Directive Conversation

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Awolowo, F.; Owolade, F.; Abidoye, A.; Dosumu, O.; Ajao, O. Towards widening participation in post-graduate research: The ASPIRE programme. People Place Policy Online 2023, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leading Routes. The Broken Pipeline: Barriers to Black PhD Students Accessing Research Council Funding; Leading Routes; 2019; Available online: www.leadingroutes.org (accessed on 20 January 2024).

- Irving, J.A.; Williams, D.I. Personal growth and personal development: Concepts clarified. Br. J. Guid. Couns. 1999, 4, 517–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devis-Rozental, C. Developing the Socio-Emotional Intelligence of Doctoral Students. Encyclopedia 2023, 3, 1178–1186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guthrie, B.; Bryant, G. Postgraduate Destinations 2014: A Report on the Work and Study Outcomes of Recent Higher Education Postgraduates; Graduate Careers Australia: Melbourne, Australia, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- McGagh, J.; Marsh, H.; Western, M.; Thomas, P.; Hastings, A.; Mihailova, M.; Wenham, M. Review of Australia’s Research Training System; Report for the Australian Council of Learned Academies; 2016; Available online: www.acola.org.au (accessed on 20 January 2024).

- Cuthbert, D.; Molla, T. The Politicization of the PhD and the Employability of Doctoral Graduates: An Australian Case Study in a Global Context. In Technology and Workplace Skills for the Twenty-First Century: Asia Pacific Universities in the Globalized Economy; Neubauer, D.E., Ghazali, D., Eds.; Palgrave Macmillan: New York, NY, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Wendler, C.; Bridgeman, B.; Cline, F.; Millett, C.; Rock, J.; Bell, N.; McAllister, P. The Path Forward: The Future of Graduate Education in the United States; Educational Testing Service: Princeton, NJ, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

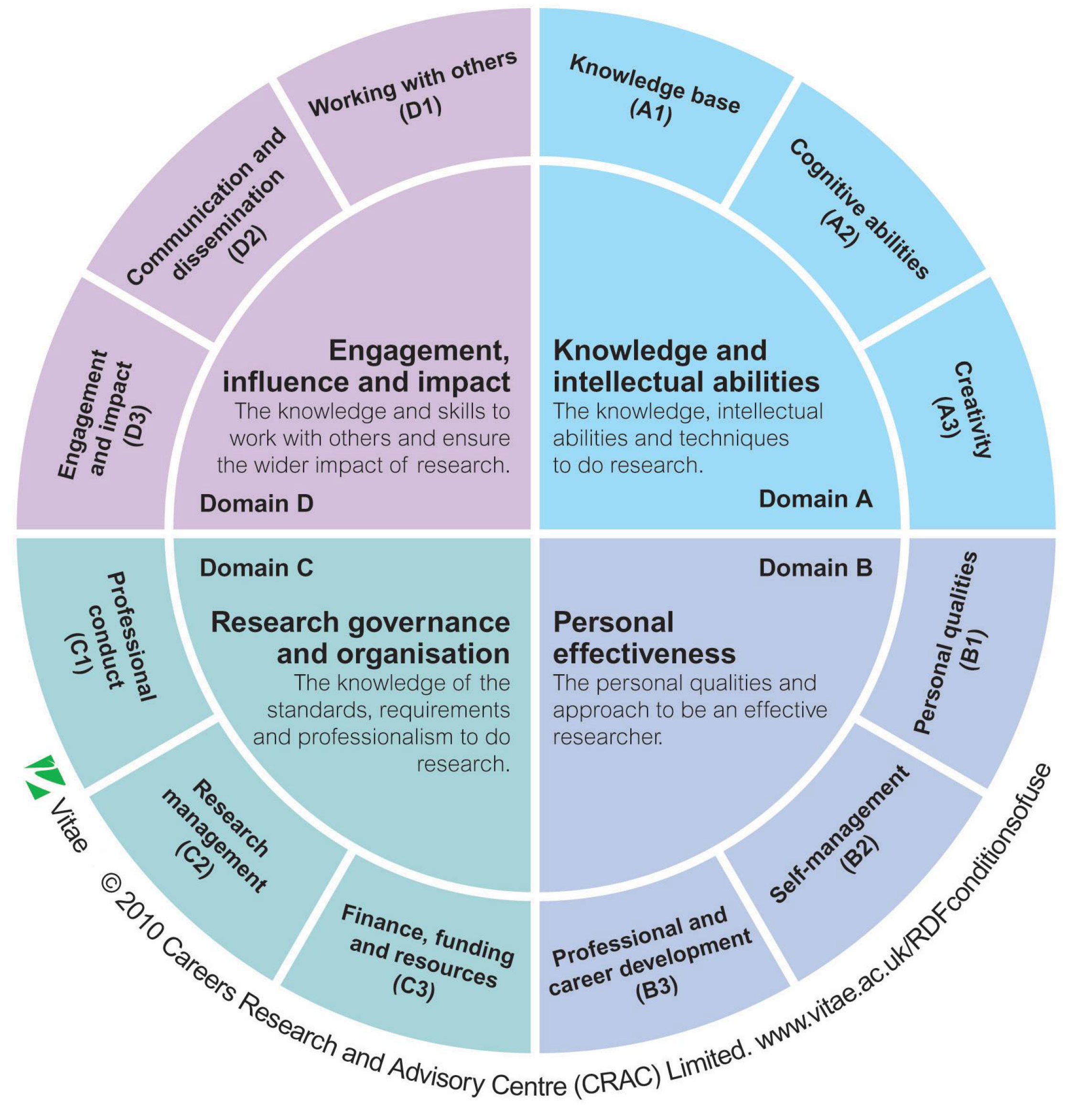

- Vitae. The Researcher Development Framework; 2023; Available online: https://www.vitae.ac.uk/researchers-professional-development/about-the-vitae-researcher-development-framework (accessed on 20 January 2024).

- Advance HE. Professional Standards Framework (PSF2023); 2023; Available online: https://www.advance-he.ac.uk/teaching-and-learning/psf (accessed on 20 January 2024).

- UKCGE. Supporting Excellent Supervisory Practice across UKRI Doctoral Training Investments; 2023; Available online: https://www.ukri.org/publications/supporting-excellent-supervisory-practice-across-ukri-doctoral-training-investments/ (accessed on 20 January 2024).

- UNICEF. Global Framework on Transferable Skills; 2019; Available online: https://www.unicef.org/reports/global-framework-transferable-skills (accessed on 20 January 2024).

- Hawkins, P.; Smith, N. Coaching, Mentoring and Organizational Consultancy: Supervision, Skills and Development, 2nd ed.; Open University Press: Maidenhead, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Gardner, H. Multiple Intelligences: New Horizon; Basic Books: New York, NY, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Durham University. Graduate Attributes; 2023; Available online: https://www.durham.ac.uk/about-us/graduate-attributes/ (accessed on 20 January 2024).

- Showunmi, V.; Younas, F.; Morrison Gutman, L. Inclusive Supervision: Bridging the Cultural Divide. Encyclopedia 2024, 4, 186–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gatfield, T. An Investigation into PhD Supervisory Management Styles: Development of a dynamic conceptual model and its managerial implications. J. High. Educ. Policy Manag. 2005, 27, 311–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boehe, D. Supervisory styles: A contingency framework. Stud. High. Educ. 2014, 41, 399–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vehviläinen, S.; Löfström, E. “I wish I had a crystal ball”: Discourses and potentials for developing academic supervising. Stud. High. Educ. 2016, 41, 508–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruce, C.; Stroodley, I. Experiencing higher degree research supervision as teaching. Stud. High. Educ. 2011, 38, 226–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guccione, K.; Hutchinson, S. Coaching and Mentoring for Academic Development; Series: Surviving and Thriving in Academia; Emerald Publishing Limited: Bingley, UK, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Hawkins, P.; Smith, N. Coaching, Mentoring and Organizational Consultancy: Supervision and Development; Open University Press: Maidenhead, UK, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Whitmore, J. Coaching for Performance: Growing Human Potential and Purpose, 4th ed.; Hachette: London, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Devenish, R.; Dyer, S.; Jefferson, T.; Lord, L.; van Leeuwen, S.; Fazakerley, V. Peer to peer support: The disappearing work in the doctoral student experience. High. Educ. Res. Dev. 2009, 28, 59–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Meschitti, V. Can peer learning support doctoral education? Evidence from an ethnography of a research team. Stud. High. Educ. 2019, 44, 1209–1221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flores-Scott, E.M.; Nerad, M. Peers in doctoral education: Unrecognized learning partners. New Dir. High. Educ. 2012, 157, 73–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McConnell, K.; Geesa, R.L.; Lowery, K. Self-reflective mentoring: Perspectives of peer mentors in an education doctoral program. Int. J. Mentor. Coach. Educ. 2019, 8, 86–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, M. Understanding the Role of Social Support in the Association between Loneliness and Well-Being for STEM Graduate Students. Ph.D. Thesis, No. 10681329. Arizona State University, Tempe, AZ, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Casey, C.; Taylor, J.; Knight, F.; Trenoweth, S. Understanding the Mental Health of Doctoral Students. Encyclopedia 2023, 3, 1523–1536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Golding, J. Supporting Doctoral Students in Crisis. Encyclopedia 2023, 3, 1197–1207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Riby, D.M.; Rees, S. Personal Development of Doctoral Students. Encyclopedia 2024, 4, 743-752. https://doi.org/10.3390/encyclopedia4020047

Riby DM, Rees S. Personal Development of Doctoral Students. Encyclopedia. 2024; 4(2):743-752. https://doi.org/10.3390/encyclopedia4020047

Chicago/Turabian StyleRiby, Deborah M., and Simon Rees. 2024. "Personal Development of Doctoral Students" Encyclopedia 4, no. 2: 743-752. https://doi.org/10.3390/encyclopedia4020047

APA StyleRiby, D. M., & Rees, S. (2024). Personal Development of Doctoral Students. Encyclopedia, 4(2), 743-752. https://doi.org/10.3390/encyclopedia4020047