Abstract

The prevalence of end-stage renal disease has surged significantly in recent decades, with an 88% increase reported in the United States between 2002 and 2022. Peritoneal dialysis and home hemodialysis offer numerous advantages over in-center hemodialysis, including improved quality of life, increased treatment flexibility, and reduced healthcare costs. Despite strong preferences among healthcare professionals and the documented benefits of home-based therapies, utilization remains limited in the U.S. One of the many factors that play a role in the underutilization of home therapies is inadequate training and perceived incompetence among nephrology fellows in initiating and managing home dialysis patients. Here in this article, we highlight the current educational gaps in home dialysis training and ways to overcome the barriers. There is a need for a multifaceted approach that includes home dialysis rotations and continuity clinics; a dedicated one-year Home Dialysis Fellowship; and continued medical education through didactics, symposiums, and conferences. Here we emphasize the need for structured, longitudinal programs that combine didactic learning with hands-on clinical in fellowship trainings and the importance of dedicated one-year fellowships in cultivating future leaders and experts in the field. By enhancing training pathways and expanding fellowship opportunities, nephrology education can better equip physicians to meet the growing demand for home dialysis, ultimately improving patient outcomes and advancing public health objectives.

1. Introduction

The latest United States Renal Data System (USRDS) data shows an 88% increase in the prevalence of end-stage kidney disease (ESKD) between 2002 and 2022 [1]. Peritoneal dialysis and home hemodialysis offer several benefits compared to in-center hemodialysis. Both modalities provide greater flexibility and autonomy, allowing patients to dialyze at home and tailor treatment schedules to their lifestyle, which can improve quality of life and facilitate employment and social participation [2,3,4]. Clinical outcomes may also differ. Home hemodialysis with more frequent dialysis is associated with improved survival and lower all-cause mortality compared to in-center hemodialysis in matched cohort studies. However, the certainty of evidence is low due to confounding in observational data [5,6]. Peritoneal dialysis, in particular, is associated with better preservation of residual kidney function, fewer dietary restrictions, and lower risk of blood-borne infections than in-center hemodialysis [7,8]. Moreover, the American Heart Association states that home-based therapies, including home hemodialysis and peritoneal dialysis, may improve cardiovascular risk factors and outcomes by providing a more physiological approach to fluid and solute management, reducing rapid volume shifts, and better controlling blood pressure and left ventricular mass [9]. Cost-effectiveness is another advantage, with both home modalities generally incurring lower overall costs than in-center hemodialysis due to reduced staffing and facility needs [2,3].

In addition, most renal healthcare professionals tend to prefer home-based treatments if they had to choose a modality for themselves and for their patients. An international survey of nephrologists from Europe, Canada, and the United States showed that the majority of the providers believed that home dialysis provides better quality of life and that more frequent and longer dialysis can significantly improve clinical outcomes [10]. Another survey exploring the preferences of UK renal healthcare workers, with 858 responses, indicated a strong preference for peritoneal dialysis over in-center hemodialysis and home hemodialysis [11].

Despite the benefits and healthcare professionals’ preference for home dialysis, in-center hemodialysis (ICHD) remains the most prevalent modality. According to USRDS, only approximately 14% of incident dialysis patients in the United States (US) were started on home dialysis, and the prevalence of home dialysis is significantly lower in the US compared to other industrialized countries [1]. For example, Hong Kong has a 73% prevalence of PD use [12]. Pre-dialysis patient education plays a key role in increasing the utilization of home dialysis. Policy changes are also essential to further increase home dialysis utilization, and initiatives such as the Advancing American Kidney Health Initiative aim to increase the uptake of home dialysis by addressing some of these barriers through new payment models and quality initiatives [13].

2. Educational Gaps in Nephrology Training Programs

A significant barrier to the broader adoption of home dialysis lies in the educational gaps regarding home dialysis modalities within current nephrology fellowship training programs. Utilization of home dialysis depends on the comfort of physicians providing the dialysis care and correlates with their education, training, and experience. Lack of adequate training and perceived competence among nephrology trainees and early-career nephrologists play a significant role in less-than-optimal utilization of home dialysis, as suggested by several surveys over the years. An internet-based survey for trainees who completed a nephrology fellowship between 2004 and 2008 evaluated the self-perceived competency in various areas of nephrology. Most respondents felt well-trained and competent in many core areas of patient care. However, it revealed that only half the respondents felt they had been well-trained in PD and only 15% in HHD [14]. A second survey-based needs assessment provided a comprehensive evaluation of the educational needs and gaps perceived by nephrology fellows. This study showed that fellows perceive several gaps in their training, particularly in home dialysis modalities, and about 45% of the fellows expressed interest in additional instruction in these areas to better prepare for independent practice [15]. Another study surveyed the nephrology fellows attending Home Dialysis University courses in 2019 and provided a detailed examination of the current state of home dialysis training. It concluded that nephrology trainees perceive low to moderate levels of preparedness for managing HHD and PD, respectively. In addition, nearly all wanted more home dialysis-focused teaching at their programs [16].

A 2022 survey conducted by the American Society of Nephrology assessed home dialysis training from the perspective of nephrology program directors and division chiefs. Only 72% of program directors reported that all fellows could independently provide peritoneal dialysis upon graduation, and only 30% felt the same for home hemodialysis, underscoring a critical training gap. The study found that most program directors and division chiefs agreed that 10–12 clinic sessions were the minimum needed for fellows to achieve competency, and 74% of program directors expressed strong interest in a virtual, case-based home dialysis mentorship program, thus reinforcing the urgent need to standardize and enhance training in home modalities [17].

These studies and surveys highlight the gaps in training and education and limit the confidence of nephrologists in recommending and managing these modalities. This, in turn, results in hindering the uptake of home dialysis. Thus, enhancing the pathways towards home dialysis education for nephrology fellows is essential to ensuring that they acquire the necessary skills and confidence to manage patients on home dialysis.

3. Strategies to Improve Home Dialysis Education

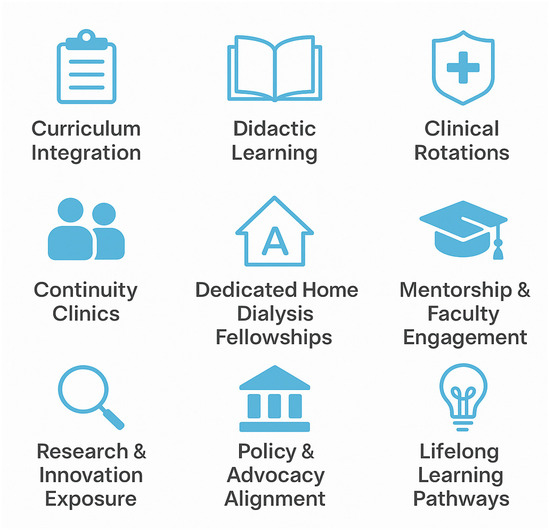

To address the educational gaps in current nephrology training programs, a multi-faceted approach is needed. Strategies can include improving home dialysis didactics, providing hands-on experience with patient care, and offering mentorship from experienced faculty, as summarized in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Home dialysis education strategies.

3.1. Didactic Learning

There are several home dialysis education programs that provide extensive teaching on home dialysis topics. Home Dialysis University, Annual Dialysis Conference, and ASN Kidney Week are some of such educational programs at the national level. The Home Dialysis University is an in-person course for nephrology fellows that is designed to provide in-depth education, including topics on physiology, prescription writing, long-term care, and the infrastructure of a home dialysis unit. It includes didactic and small group sessions that encourage interaction with faculty to learn approaches for use in clinical practice. The Annual Dialysis Conference and ASN Kidney Week have courses and sessions dedicated to home dialysis.

The International Society for Peritoneal Dialysis (ISPD) also offers educational opportunities designed to promote the advancement of PD knowledge and practice globally. One of their initiatives is the ISPD Online Lecture Series, which features over twenty expert-led video modules covering a broad range of PD-related topics. Delivered by renowned international specialists, these lectures provide learners with accessible, high-quality education, and more modules with updated information are continuously being developed. There is also the opportunity to participate in the Virtual Journal Club Series, supported by the ISPD North America Chapter, which enhances PD education through dynamic, multi-time zone discussions of the latest and most impactful PD research. Its virtual format increases accessibility and inclusivity, allowing trainees and practitioners from across the U.S. and Canada to participate in scholarly dialog and knowledge exchange. Together, these programs reflect ISPD’s commitment to comprehensive, accessible, and innovative PD education.

Additionally, there are numerous regional symposiums and programs that provide further exposure to trainees and nephrologists on core topics, as well as challenges and innovations in the field. While didactic learning provides foundational knowledge on home dialysis modalities, it is not sufficient on its own and cannot replace the value of practical clinical experience. Optimal education requires a comprehensive approach that integrates structured didactics with direct patient care experiences.

3.2. Home Dialysis Rotations and Continuity Clinics

Adequate hands-on clinical experience is required for the nephrology fellows to feel confident in not only managing patients on home dialysis but also encouraging patients to choose these modalities. This can be achieved through home dialysis rotation during the general nephrology training, continuity clinics, didactic learning, and/or a dedicated one-year fellowship after the general nephrology training [18]. During general nephrology training, home dialysis rotation and continuity clinics can provide trainees with the opportunity to participate in patient selection and training, monthly visits, staff meetings, and troubleshooting clinical problems and complications as they arise. By taking on responsibilities such as managing treatment orders, providing patient education, and ensuring proper documentation, trainees develop a deeper understanding of the complexities and challenges of home dialysis care. In addition to short rotations, continuity clinics provide another valuable avenue for skill development. These clinics offer trainees the opportunity to follow patients longitudinally, gaining insights into disease progression, treatment adherence, and long-term management. However, for this experience to be truly effective, nephrology training programs must have access to well-established home dialysis units with sufficient patient volumes and expert faculty mentors who can guide and support trainees.

Currently, the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) requires that nephrology fellows demonstrate competence in the management of home dialysis therapies, including PD and HHD, by the completion of fellowship training [19]. However, ACGME does not specify a minimum number of required patient encounters or procedures for home dialysis, nor does it mandate a specific curriculum structure. The American Board of Internal Medicine (ABIM), after recognizing the gaps in home dialysis education, has strengthened its requirements for home dialysis training [20]. ABIM now requires nephrology fellows to competently complete at least eight peritoneal dialysis clinic sessions and two training sessions during their fellowship. Noting the interdisciplinary nature of peritoneal dialysis, ABIM stresses and requires trainees to be sufficiently exposed to peritoneal dialysis in an outpatient setting. It also states that the home hemodialysis procedural experience must be provided at an “Opportunity to Train” standard. The “Opportunity to Train” standard requires programs to train nephrology fellows to competency if requested by the trainee. In addition, all nephrology fellows should be able to demonstrate knowledge of the indications, contraindications, limitations, complications, alternatives, and techniques of home hemodialysis.

Providing an adequate volume of home dialysis clinical experience can be challenging for smaller training programs that are not associated with large home dialysis units. Such programs can liaise with one of the larger home dialysis programs and arrange for their trainees to rotate through and gain hands-on experience in managing home dialysis patients. Malpractice coverage can sometimes be challenging to obtain in such scenarios, and in these cases, shadowing or observership could be arranged.

Regular interactions with patients help trainees develop the confidence and communication skills necessary to encourage patients to consider home dialysis modalities. For those interested in becoming home dialysis specialists and experts, a dedicated fellowship in home dialysis after general nephrology training can provide an even more in-depth and structured experience.

3.3. Home Dialysis Fellowships

The Home Dialysis Fellowship is designed to train future leaders, educators, and experts in the field of home dialysis, ensuring that they possess the specialized skills required to advance this growing area of nephrology. As in any other medical specialty, achieving a high level of competence demands rigorous, structured, and longitudinal training that combines didactic learning with extensive hands-on experience. The rising demand for home dialysis services has led to an increasing number of healthcare institutions seeking dedicated nephrologists to initiate, expand, and optimize home dialysis programs in both academic medical centers and private nephrology practices. As a result, formal training in home dialysis has become even more valuable, equipping physicians with the expertise necessary to improve patient outcomes, enhance program efficiency, and contribute to the advancement of home-based therapies. To the best of our knowledge, only a few programs, namely Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai in New York, Vanderbilt University Medical Center in Nashville, and Indiana University School of Medicine in Indianapolis offer a dedicated one-year Home Dialysis Fellowship in the U.S. Canada also has multiple institutions offering Home Dialysis Fellowship, including University of Toronto, University of British Columbia, Western University in Ontario, University of Calgary, McMaster University in Ontario, and Sunnybrook Health Sciences Centre in Ontario. Having similar programs more readily available can increase the number of fellows training in home dialysis. The key components of a Home Dialysis Fellowship are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Key components of Home Dialysis Fellowship training.

Here at Mount Sinai Home Dialysis Fellowship, the program includes hands-on training under the supervision of nephrologists dedicated to home dialysis. The training involves comprehensive management of 80–90 home dialysis patients in an outpatient program, with longitudinal follow-up for a year. It includes monthly clinic visits, held twice weekly, as well as day-to-day support visits and phone calls to address problems and complications that may arise. Fielding calls from nurses and patients to address acute issues under the supervision of attendings provides fellows with the exposure and experience they need to practice independently. In addition to managing existing patients, fellows perform pre-dialysis patient assessments alongside a multidisciplinary team. They are responsible for managing and supervising new training sessions for PD and HHD, as well as troubleshooting any problems that occur during training. During the year, core curriculum topics, including, but not limited to, physiology, machine setup and alarms, prescription management, evaluation and management of complications, structure of ESRD network, CMS conditions of coverage, and quality evaluation and improvement, are covered in detail. Table 2 summarizes key curriculum topics organized by training category. To cover these topics, fellows meet with the attending physicians as well as with key interdisciplinary staff members, including the nurse manager, dialysis nurses, dialysis educator, renal dietitian, social worker, and dialysis unit administrator. Fellows also gain procedural experience by observing the placement of PD catheters and arteriovenous access with surgeons and interventional radiologists. They develop essential professional skills by establishing effective working relationships and communication with vascular and peritoneal access surgeons and/or IR specialists. Active participation in weekly staff meetings and monthly quality assurance and performance improvement meetings is a key component of the fellowship. Additionally, fellows contribute to the education of general nephrology fellows and assist in managing admitted home dialysis patients, further enhancing their clinical and teaching skills.

Table 2.

Core curriculum topics in home dialysis training.

In addition to the one-year fellowships, ISPD offers a fellowship program that supports practical and hands-on training for future PD leaders. This program enables eligible individuals to spend up to three months at a well-established PD center that has expertise in training new PD specialists. The program also offers funding to support travel and training-related costs. It is offered at multiple places across the world, making it an excellent opportunity for trainees from around the globe.

3.4. Project Echo

In the National Kidney Foundation–Kidney Disease Outcomes Quality Initiative (NKF-KDOQI) conference report on home dialysis, a “hub and spoke” model using Project ECHO (Extension for Community Healthcare Outcomes) as a framework is proposed as a valuable model to address the widespread educational and support gaps among nephrologists and dialysis care teams [21,22]. It recommends a virtual, case-based telementoring approach where expert teams at central “hub” institutions provide structured education and mentorship to community “spoke” sites via videoconferencing. Such programs can help build provider confidence by offering real-time, practical guidance on initiating and managing home dialysis, troubleshooting complications, and supporting patient and caregiver education. These virtual mentorship initiatives would allow community nephrologists, especially those in smaller or underserved centers, to benefit from the expertise of established home dialysis programs, thereby enhancing their ability to offer and maintain these therapies. It allows for scalable, ongoing mentorship and case-based learning, overcoming geographic and resource limitations [23].

Moreover, the ECHO model fits within a broader strategy of using technology to expand educational access and create consistent messaging across dialysis care teams. The report envisions a future where comprehensive, simulation-based training modules become a standard part of nephrology education both during and after fellowship. These efforts are aimed not only at increasing provider knowledge but also at fostering a more patient-centered, collaborative care environment. Ultimately, leveraging models like Project ECHO could play a central role in scaling up the adoption of home dialysis nationwide by ensuring that all providers have the knowledge, tools, and support needed to offer this modality confidently and competently.

3.5. Continuing Professional Education

Continuing Professional Education (CPE) in home dialysis plays a vital role in addressing the widespread knowledge and confidence gaps among nephrologists regarding home-based kidney replacement therapies [23]. Traditional CPE methods, such as in-person workshops and annual conferences, offer some value but have limitations in scalability, accessibility, and depth of engagement. While conferences like the Annual Dialysis Conference and NKF-KDOQI meetings do include home dialysis content, they are often not the central focus, and participation is restricted to those who can travel and attend. In response, various educational initiatives have emerged, ranging from short courses and hands-on workshops to asynchronous online modules, slide decks, and webinars.

Importantly, CPE in home dialysis has begun evolving toward virtual, interactive models. Programs like Project ECHO and similar tele-mentoring initiatives aim to create virtual communities of practice, where clinicians engage in regular sessions that combine didactic instruction with case-based discussions. Interactive, mentor-led, and virtually accessible education models are needed to meaningfully increase home dialysis adoption and equip experienced clinicians with the competencies required to manage these therapies effectively.

3.6. OSCE

Simulation-based assessments, such as objective structured clinical examinations (OSCEs), have been developed to supplement clinical experience and provide formative feedback on proficiency in home hemodialysis, further supporting competency-based education [24]. The OSCE consisted of 27 items (31 possible points), including 7 evidence-based or standard-of-care questions. A test committee, comprising HHD-experienced clinicians and one care partner, assessed item relevance and established a passing threshold of 65% (20/31 points). In validation testing, board-certified nephrologists (mean score 27.5/31) outperformed nephrology fellows (mean score 21.5/31). Validators scored correctly 88% of evidence-based/standard-of-care questions vs. 62% by fellows (p < 0.001). Notably, 42% of fellows were able to name four benefits and two risks of HHD, and 29% correctly identified the minimum standard weekly Kt/V target.

Despite these gaps, the majority of fellows (88%) found the OSCE useful in self-assessing their HHD proficiency. The study concludes that this OSCE may be a valuable formative tool for assessing HHD knowledge and clinical skills in nephrology fellows and could support curriculum development in programs where hands-on HHD exposure is limited.

4. Organizational Culture and Home Dialysis Uptake

Improving home dialysis uptake and maintenance requires more than just enhancing education for nephrology fellows; it also demands a parallel focus on education and transformation at the organizational level. While clinical training equips future nephrologists with the technical knowledge and confidence to support home therapies, the broader institutional environment in which they practice also plays a critical role. Organizational culture can be an important determinant of home dialysis adoption [25]. An ethnographic investigation explored how cultural and organizational practices within kidney centers influence patients’ willingness and ability to choose home dialysis. Their findings emphasize the importance of fostering a patient-centered environment where individual circumstances are acknowledged, psychosocial support is integrated, and staff actively engage with patients’ cultural and economic contexts. Centers that encouraged patient voices, offered peer support, and worked to overcome barriers such as housing or language differences were more effective in supporting patients to choose home dialysis. Sustained success was also linked to leadership commitment, quality improvement cultures, and engagement with broader networks beyond the clinic.

These qualitative insights are also supported by the findings of Castledine et al., who identified significant variation in home dialysis use across UK renal centers, much of which could not be explained by patient factors alone [26]. Physician attitudes and center-level practices, such as early PD initiation, availability of home visits for pre-dialysis education, and troubleshooting support for existing home dialysis patients, were strong predictors of higher uptake. Centers where physicians aspired to greater use of home therapies demonstrated markedly better adoption rates, reinforcing the importance of staff beliefs and leadership in shaping treatment patterns.

Findings from another English kidney center’s survey also affirm these conclusions [27]. The survey found that several aspects of organizational culture demonstrated moderate to strong associations. Supportive clinical leadership, a culture open to new initiatives, reflective practice, engagement with research, and quality improvement efforts were all significantly correlated with higher home dialysis rates. The availability of assisted peritoneal dialysis and providing flexible, patient-led decision-making about dialysis modality were the only specific service delivery practices to show similarly strong links.

Increasing home dialysis uptake requires impactful interventions that target the organizational culture, including creating an environment where supportive leadership, staff engagement, patient empowerment, and a sustained commitment to improvement can thrive. These cultural and relational dimensions are essential for an equitable, scalable, and effective home dialysis program to be built.

5. Conclusions

Specialized training can enhance nephrologists’ confidence and competence in managing home dialysis. This, in turn, can translate into an increased use of home dialysis. As more nephrologists gain proficiency in home-based therapies, more patients may be encouraged to consider PD and HHD as viable treatment options, contributing to broader adoption rates. Beyond clinical practice, specialized training can also promote research and innovation in home dialysis, driving the development of new technologies, improved protocols, and evidence-based best practices that enhance both patient safety and treatment efficacy [10]. Enhanced training through a dedicated fellowship can also help meet these policy objectives by providing focused education and hands-on experience [28,29]. Addressing the educational gaps in home dialysis training is essential to meet the growing need for skilled nephrologists capable of managing home dialysis modalities. Expanding specialized training opportunities can bridge these gaps by providing comprehensive didactics, hands-on clinical experience, and mentorship. These initiatives enhance nephrologists’ confidence and competence, aligning with public health goals aimed at increasing home dialysis users. Equipping nephrology fellows with the necessary knowledge and skills, along with education and cultural changes at an organizational level, can promote the broader adoption of home dialysis, reduce healthcare costs, and improve patient outcomes. A multifaceted approach incorporating structured curricula, clinical exposure, and innovative teaching strategies will be critical to achieving these objectives and fostering innovation in home dialysis practices.

Author Contributions

Both authors made equal contributions to the manuscript. I.D.S.-L. performed the literature search, writing and revisions of the manuscript. S.S. contributed by supervising, writing, reviewing and editing the manuscript. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- United States Renal Data System. Home Dialysis. 2024. Available online: https://usrds-adr.niddk.nih.gov/2024/end-stage-renal-disease/2-home-dialysis (accessed on 28 February 2025).

- Quinn, R.R.; Lam, N.N. Home dialysis in North America: The current state. Clin. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2023, 18, 1351–1358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bello, A.K.; Okpechi, I.G.; Osman, M.A.; Cho, Y.; Cullis, B.; Jha, V.; Makusidi, M.A.; McCulloch, M.; Shah, N.; Wainstein, M.; et al. Epidemiology of peritoneal dialysis outcomes. Nat. Rev. Nephrol. 2022, 18, 779–793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morfín, J.A.; Yang, A.; Wang, E.; Schiller, B. Transitional dialysis care units: A new approach to increase home dialysis modality uptake and patient outcomes. Semin. Dial. 2018, 31, 82–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheetham, M.S.; Ethier, I.; Krishnasamy, R.; Cho, Y.; Palmer, S.C.; Johnson, D.W.; Craig, J.C.; Stroumza, P.; Frantzen, L.; Hegbrant, J.; et al. Home versus in-centre haemodialysis for people with kidney failure. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2024, 4, CD009535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yeung, E.K.; Polkinghorne, K.R.; Kerr, P.G. Home and facility haemodialysis patients: A comparison of outcomes in a matched cohort. Nephrol. Dial. Transplant. 2021, 36, 1070–1077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ethier, I.; Hayat, A.; Pei, J.; Haeley, C.M.; Francis, R.S.; Wong, G.; Craig, J.C.; Viecelli, A.K.; Htay, H.; Ng, S.; et al. Peritoneal dialysis versus haemodialysis for people commencing dialysis. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2024, 6, CD013800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sinnakirouchenan, R.; Holley, J.L. Peritoneal dialysis versus hemodialysis: Risks, benefits, and access issues. Adv. Chronic Kidney Dis. 2011, 18, 428–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarnak, M.J.; Auguste, B.L.; Brown, E.; Chang, A.R.; Chertow, G.M.; Hannan, M.; Herzog, C.A.; Nadeau-Fredette, A.; Tang, W.H.; Wang, A.Y.; et al. Cardiovascular effects of home dialysis therapies: A scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation 2022, 146, e146–e164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fluck, R.J.; Fouque, D.; Lockridge, R.S. Nephrologists’ perspectives on dialysis treatment: Results of an international survey. BMC Nephrol. 2014, 15, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamer, R.; Hameed, A.; Damery, S.; Jenkins, K.; Dasgupta, I.; Baharani, J. Do we practice what we preach? Dialysis modality choice among healthcare workers in the United Kingdom. Semin. Dial. 2023, 36, 407–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, P.K.T.; Chow, K.M.; Van de Luijtgaarden, M.W.; Johnson, D.W.; Jager, K.J.; Mehrotra, R.; Naicker, S.; Pecoits-Filho, R.; Yu, X.Q.; Lameire, N. Changes in the worldwide epidemiology of peritoneal dialysis. Nat. Rev. Nephrol. 2017, 13, 90–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abra, G.; Schiller, B. Public policy and programs—Missing links in growing home dialysis in the United States. Semin. Dial. 2020, 33, 75–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berns, J.S. A survey-based evaluation of self-perceived competency after nephrology fellowship training. Clin. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2010, 5, 490–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rope, R.W.; Pivert, K.A.; Parker, M.G.; Sozio, S.M.; Merell, S.B. Education in nephrology fellowship: A survey-based needs assessment. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2017, 28, 1983–1990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, N.; Taber-Hight, E.B.; Miller, B.W. Perceptions of home dialysis training and experience among US nephrology fellows. Am. J. Kidney Dis. 2021, 77, 713–718.e1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reddy, Y.N.; Berns, J.S.; Bansal, S.; Simon, J.F.; Murray, R.; Jacob, M.; Perl, J.; Gould, E. Home dialysis training needs for fellows: A survey of nephrology program directors and Division Chiefs in the United States. Kidney Med. 2023, 5, 100629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gupta, N.; Miller, B.W. Training nephrology fellows in home dialysis in the United States. Clin. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2021, 16, 1749–1751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nephrology Policies. ABIM. Available online: https://www.abim.org/certification/policies/internal-medicine-subspecialty-policies/nephrology/ (accessed on 6 June 2025).

- ACGME Program Requirements for Graduate Medical Education in Nephrology. Available online: https://www.acgme.org/globalassets/pfassets/programrequirements/2024-prs/148_nephrology_2024.pdf (accessed on 6 June 2025).

- Chan, C.T.; Collins, K.; Ditschman, E.P.; Koester-Wiedemann, L.; Saffer, T.L.; Wallace, E.; Rocco, M.V. Overcoming barriers for uptake and continued use of home dialysis: An NKF-KDOQI conference report. Am. J. Kidney Dis. 2020, 75, 926–934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, C.T.; Wallace, E.; Golper, T.A.; Rosner, M.H.; Seshasai, R.K.; Glickman, J.D.; Schreiber, M.; Gee, P.; Rocco, M.V. Exploring barriers and potential solutions in home dialysis: An NKF-KDOQI conference outcomes report. Am. J. Kidney Dis. 2019, 73, 363–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashley, J.; Abra, G.; Schiller, B.; Bennett, P.N.; Mehr, A.P.; Bargman, J.M.; Chan, C.T. The use of virtual physician mentoring to enhance home dialysis knowledge and uptake. Nephrology 2021, 26, 569–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, J.A.; Tobin, T.W.; Bermudez, M.C.; Braden, G.L.; Fisher, E.; Gupta, N.; Landry, D.; LeBrun, C.; Nee, R.; Pasiuk, B.; et al. A home hemodialysis objective structured clinical examination (OSCE) for formative assessment of nephrology fellows. Clin. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2025, epub ahead of print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, K.; Shaw, K.L.; Spry, J.L.; Dikomitis, L.; Coyle, D.; Damery, S.; Fotheringham, J.; Lambie, M.; Williams, I.P.; Davies, S. How does organisational culture facilitate uptake of home dialysis? An ethnographic study of kidney centres in England. BMJ Open 2024, 14, e085754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Castledine, C.I.; Gilg, J.A.; Rogers, C.; Ben-Shlomo, Y.; Caskey, F.J. Renal centre characteristics and physician practice patterns associated with home dialysis use. Nephrol. Dial. Transplant. 2013, 28, 2169–2180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Damery, S.; Lambie, M.; Williams, I.; Coyle, D.; Fotheringham, J.; Solis-Trapala, I.; Allen, K.; Potts, J.; Dikomitis, L.; Davies, S.J. Centre variation in home dialysis uptake: A survey of kidney centre practice in relation to home dialysis organisation and delivery in England. Perit. Dial. Int. J. Int. Soc. Perit. Dial. 2024, 44, 265–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Golper, T.A.; Saxena, A.B.; Piraino, B.; Teitelbaum, I.; Burkart, J.; Finkelstein, F.O.; Abu-Alfa, A. Systematic barriers to the effective delivery of home dialysis in the United States: A report from the Public Policy/Advocacy Committee of the North American Chapter of the International Society for Peritoneal Dialysis. Am. J. Kidney Dis. 2011, 58, 879–885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schreiber, M.J.; Chatoth, D.K.; Salenger, P. Challenges and opportunities in expanding home hemodialysis for 2025. Adv. Chronic Kidney Dis. 2021, 28, 129–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).