1. Introduction

Resilience is defined as an individual’s ability to adapt, recover, and thrive in the face of adversity. Resilience is what carries an individual through their challenges, allowing the individual to grow and emerge on the other side better equipped to handle the next hurdle. Unfortunately, patients living with chronic illnesses face constant challenges. They must continually adapt to physical limitations, treatment demands, and emotional challenges while striving to maintain their quality of life.

Resilience has been recognized as a major factor in helping patients sustain emotional health, maintain adherence to treatment, and find meaning despite adversity [

1]. Research also suggests that resilience in patients is linked to better health outcomes [

2]. Patients with chronic kidney disease (CKD) and end-stage kidney disease (ESKD), especially those on peritoneal dialysis (PD), face unique stressors that make resilience essential to their long-term health and survival. Developing and maintaining resilience is essential for ESKD patients in order to manage the stressors of treatment, maintain quality of life, and optimize health outcomes.

The purpose of this paper is to explore the role of resilience in patients undergoing PD due to the high level of self-management required for PD. This paper will examine existing frameworks on resilience in patients living with chronic illness, specifically those with CKD and ESKD, and identify key challenges faced by patients receiving PD. We will describe and apply the GROW (Good emotions, Reason and purpose, Others and connections, Wellness flexibility) framework of resilience to patients on PD. We will also highlight the need for structured resilience assessments in clinical settings and propose future research directions, including the use of tools such as the Mount Sinai Resilience Scale (MSRS), to better understand and support resilience in PD patients.

2. Peritoneal Dialysis and Resilience

PD is a home-based renal replacement therapy for patients with ESKD. Unlike IHD, which requires multiple weekly visits to a dialysis center, PD allows patients to perform dialysis at home. This offers greater flexibility and autonomy for patients with ESKD. As the name suggests PD utilizes the peritoneal membrane—a highly vascularized lining of the abdominal cavity—as a natural filter to remove waste, excess fluid, and toxins from the blood through the instillation and drainage of dialysate into the peritoneal cavity [

3].

2.1. Quality of Life in PD Versus IHD

One of the primary advantages of PD is the ability to integrate treatment into daily life. Instead of scheduling around the typical 3 times a week trip to a dialysis center for IHD, PD helps to reduce disruptions to work, education and social activities. PD is also associated with better hemodynamic stability, better preservation of residual kidney function, and a reduced burden of travel and time constraints [

3]. However, the success of PD relies heavily on patient engagement, adherence to strict infection control protocols, and the ability to perform dialysis exchanges independently or with a caregiver’s support. Despite the demands of self-care, many PD patients report a strong sense of control over their treatment, which can enhance psychological resilience [

4,

5].

When comparing PD patients and patients receiving IHD, several studies have highlighted important differences in quality of life (QOL) and patient experience. A systematic review by Budhram et al. (2020) found that PD was favored in domains such as physical component score, cognitive status, role limitation due to emotional function, symptoms/problems, effects of kidney disease on daily life, sexual function, and patient satisfaction [

6]. These findings align with the idea that PD allows for increased autonomy. Patients on PD must develop self-efficacy and problem-solving skills to manage their care independently, which can be empowering, but can be a double-edged sword given the high level of responsibility. In contrast, IHD was favored in domains such as support from staff, social interaction, sleep quality, general health, and role limitation due to physical function, reflecting the structured and supervised nature of in-center dialysis, which may alleviate the burden of self-care but comes at the cost of patient autonomy [

6]. However, despite its benefits, PD can also introduce unique psychosocial challenges. Patients may face greater isolation unless they have consistent social or peer support, whereas IHD patients benefit from built-in interactions within dialysis centers [

6]. Understanding these differences is essential not only for clinical decision-making but also for guiding future research into resilience-based interventions.

2.2. Evaluating for PD Readiness: Role of Resilience

It is essential to understand the role of resilience in potential PD patients to promote treatment success and overall well-being in PD. Setting up a patient for success in PD is rooted in a detailed screening process where individuals are evaluated not only for medical eligibility, but also for their ability to manage the physical, social and emotional demands of home-based dialysis. A multidisciplinary team is involved in the decision-making process, including a nephrologist, dialysis nurse, and social worker, working together to assess overall readiness for PD. This structured screening process helps ensure that PD is both a safe and sustainable treatment option [

7,

8].

The first step in determining a patient’s eligibility for PD is a comprehensive medical evaluation. Patients should have a healthy, functional peritoneal membrane to ensure effective ultrafiltration and clearance. The presence of intra-abdominal pathology, such as extensive adhesions, hernias, or a history of complex abdominal surgeries, may affect eligibility for PD, as these conditions can interfere with peritoneal function or increase the risk of complications, including recurrent infections and catheter malfunction [

7,

8]. Once PD is initiated, adequacy of dialysis will continue to be monitored regularly to ensure treatment effectiveness, guide treatment and determine adequacy of the current renal replacement modality.

Performing PD at home requires that the environment is safe and clean to support hygienic, high-quality treatment. Patients need a clean, dedicated area for storing supplies and performing exchanges, with reliable access to water, electricity, and proper lighting. Clutter, poor sanitation, or frequent disruptions can increase the risk of infection and make daily dialysis more difficult. As a part of the screening process, a nurse or dialysis team member may assess the home environment and determine if it is suitable or recommend changes if needed. The patient and/or caregiver must also continue to maintain this environment daily [

8].

Beyond medical suitability, PD success hinges on the ability of the patient or caregiver to manage the treatment safely and consistently. The patient and/or caregiver must demonstrate adequate cognitive and physical functions necessary to perform daily exchanges, follow strict infection prevention precautions, and recognize signs of complications [

7,

9]. Emotional and psychological strength also plays a major role; patients and caregivers alike must cope with the chronic nature of dialysis, the potential for complications, and the emotional fatigue that can accompany long-term care [

9].

2.3. Challenges to Resilience in PD Treatment

Multidisciplinary health literacy interventions have been shown to improve patients’ understanding of dialysis options, especially when guided by shared decision-making [

7,

8]. However, despite this multidisciplinary approach, patients with ESKD face a wide range of emotional and practical challenges that can decrease their ability to stay resilient throughout treatment. In a global qualitative study by Nataatmadja et al., which included 26 focus groups in 6 countries with patients and caregivers, five key themes regarding treatment challenges emerged. Many patients described feeling bound to dialysis, highlighting the isolation, dependence on machines, and loss of a normal routine. Emotional struggles were frequently underrecognized by healthcare providers, pointing to a gap in mental health support. An uncertain future including fear of complications and confronting mortality, added further emotional strain. The demand for self-reliance in managing treatment, staying motivated, and regulating emotions was another major stressor. Finally, patients spoke of dealing with a complete lifestyle overhaul, especially with 3 times a week in IHD. Patients also felt guilt due to the burden on family and the effort to maintain independence [

10]. Although PD fosters independence and can enhance quality of life, the autonomy it demands may not always be seen as a positive. For some, managing their own treatment can be empowering, while for others the level of responsibility can feel overwhelming. Patients must perform sterile exchanges multiple times a day or use an automated cycler overnight, maintain infection control, and manage their equipment and supplies. This intensive self-management can take a significant emotional toll. Without strong social support, patients may become more susceptible to fatigue, burnout, and depression, which in turn can lead to poor adherence and, in some cases, transition to IHD. Sustained motivation is especially challenging when compounded by physical discomfort or psychological distress. Without adequate psychosocial and clinical support, it becomes increasingly difficult to maintain the resilience required for a complex, long-term therapy like PD [

9].

3. Models of Resilience

In order for providers to address emotional distress, knowledge of psychological frameworks become valuable as a tool to understand, support and sustain treatment in chronic illness such as ESKD. Several well-established models attempt to define the components of resilience and explain how individuals adapt to adversity. One of the most widely cited is the Ten Elements of Resilience by Southwick et al., which includes the following core components: realistic optimism, confronting fears, following one’s moral compass, religion/spirituality, bidirectional social support, emulating role models, physical health, brain health (challenging the mind), cognitive and emotional flexibility, and finding meaning, purpose and growth after trauma. This model was developed through studies of individuals facing extreme stress, such as trauma survivors and military veterans, and is applied broadly to people coping with chronic hardship [

11].

Similarly, Seligman’s PERMA model presents a theory of well-being built around five elements: positive emotion, engagement, relationships, meaning, and accomplishment. The model emphasizes that psychological flourishing occurs when individuals experience a balance of these elements. Each one is cultivated and developed with practice and targeted interventions [

12].

3.1. GROW Model of Resilience and Impact on Kidney Disease

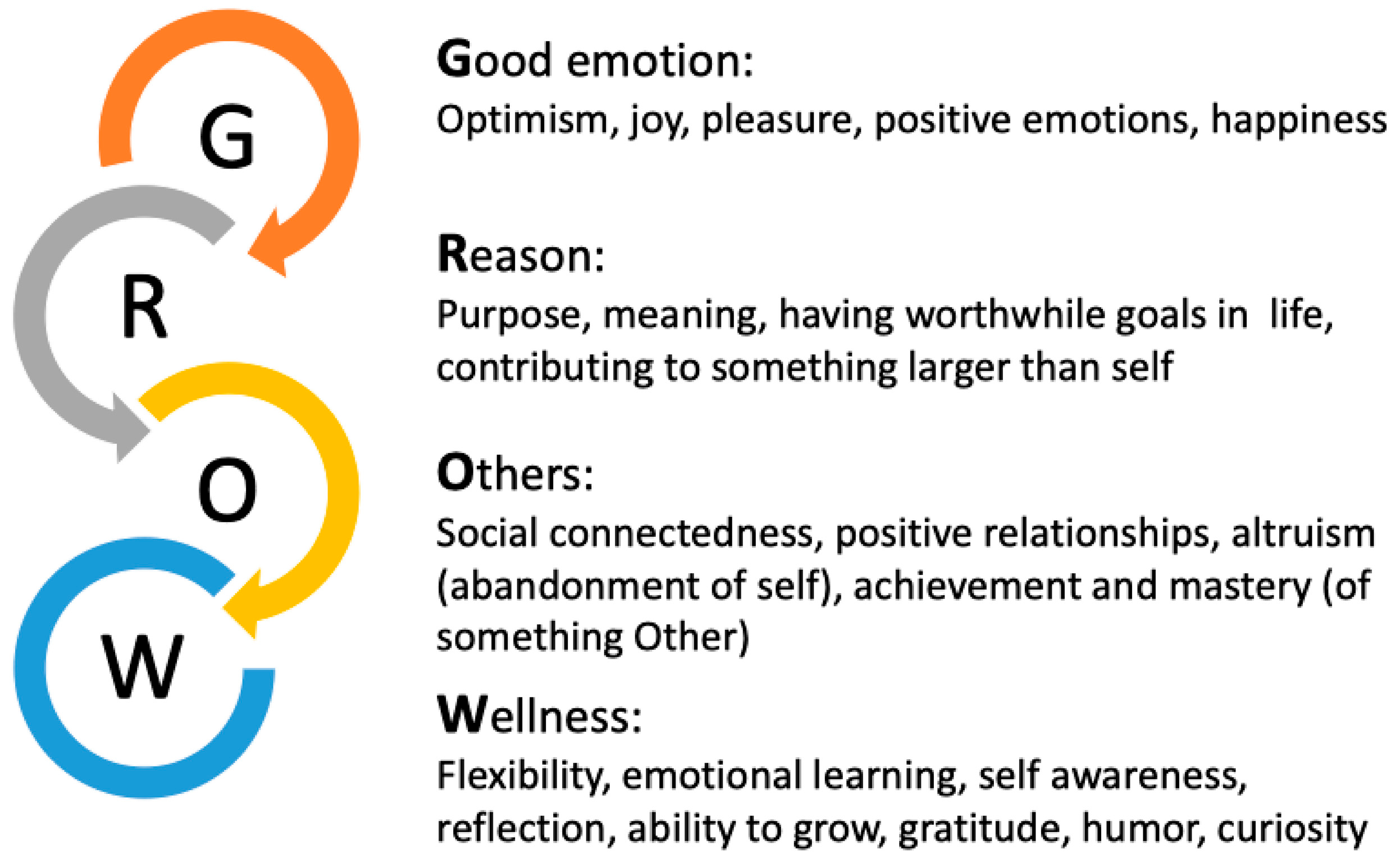

Though models like the Ten Elements of Resilience and PERMA may offer insight, they were not developed specifically for people living with chronic illness. To address this, Peccoralo et al. created the simplified GROW model designed to support resilience-building in patients managing long-term medical conditions (

Figure 1). This model was created using the aforementioned models and aligning the frameworks with the current evidence for resilience in chronic illness. GROW stands for Good Emotions, Reason and Purpose, Others, and Wellness Flexibility. In the context of PD, the GROW model offers a simple structure through which resilience can be easily understood, evaluated and encouraged in the clinical setting [

2].

3.1.1. Good Emotions

The first pillar of the GROW framework,

Good Emotions, focuses on the role of positive emotional states in sustaining resilience, especially for individuals facing chronic and complex illnesses. Positive feelings such as hope, gratitude, and joy are not merely psychological comforts; they are clinically significant and serve as vital psychological resources for people living with chronic diseases. Before Seligman introduced the PERMA model, his earlier theories of well-being highlighted positive psychology, which focuses on three “lives”: the pleasant life (centered on cultivating positive feelings), the engaged life (marked by deep involvement and flow), and the meaningful life (driven by a sense of purpose and connection to something larger). Good emotions correspond most closely with the pleasant life, encouraging patients to identify, and reflect on sources of positivity in daily life (i.e., optimism) [

2]. GROW emphasizes realistic optimism, not blind optimism. Realistic optimism considers the actual probability of a hopeful outcome, whereas blind optimism underestimates risk, overestimates ability, and/or leads to inadequate preparation. In chronic illness care, developing realistic optimism can help patients remain hopeful while making informed decisions, ultimately supporting emotional resilience and treatment adherence [

2].

Optimism has been associated with higher adherence to medical therapies [

13] and more healthy behaviors in patients with CKD [

13,

14]. Among African American patients with heart disease, optimism was linked to a 30% lower odds of CKD at baseline and 50% lower odds of rapid kidney function decline over seven years [

15]. Similarly, hope has been shown to improve psychological adjustment to dialysis in patients with ESKD [

1]. On the other hand, negative emotions—specifically, the perception that kidney disease disrupts daily life—have been associated with shortened or incomplete treatments in both PD and HD patients [

16].

3.1.2. Reason and Purpose

The second pillar of the GROW model, Reason and Purpose, focuses on helping patients connect with what gives their life meaning beyond their illness. This domain encourages patients to look beyond the daily demands of their condition and identify the motivations that keep them going, such as caring for family, career, creativity, or contributing to their community. Determining a patient’s “why” can shift the focus from their medical illnesses and challenges to a purpose in life that is worth pursuing. Connecting with one’s purpose does not make hardship go away, but it can help patients focus on meaningful goals and actions in their lives [

2].

Research supports connections between purpose, well-being and resilience. In older adults, a strong sense of purpose has been associated with better physical and mental health outcomes, lower healthcare costs, and greater use of preventive health services [

17,

18]. In patients with CKD or ESKD, higher levels of self-efficacy and personal control have been linked to better self-management, fewer symptoms, and reduced all-cause mortality [

19,

20]. Lower feelings of control were associated with shortened treatments for patients on PD and HD [

16] and lower overall well-being [

21]. In addition, a sense of self-efficacy or a personal purpose in life is associated with greater self-management behaviors in patients with CKD and ESKD [

19,

22], and better self-care behaviors and higher quality of life in patients with hypertension and CKD [

23]. Self-efficacy is also associated with fewer symptoms in patients with ESKD, including fewer persistent subjective cognitive symptoms and lower distress [

20,

24,

25]. Finally, self-efficacy is associated with a decreased risk of all-cause mortality in patients with CKD [

19]. While purpose and self-efficacy cannot erase chronic illness; they can give patients meaning, reason and control in their lives.

3.1.3. Others and Connections

The third pillar, Others and Connections, focuses on the importance of relationships and social connection. Chronic illness can be isolating. Patients on PD may spend a lot of time managing their care alone and, over time, isolation can lead to depression [

1,

9,

21]. This part of the GROW model reminds us that this journey does not have to be taken alone. Support systems not only help with tasks; they offer emotional support, reassurance and motivation. Studies have shown that people with stronger social ties do better, not just emotionally, but physically too [

17]. There is also the complementary idea of turning outward through fostering altruism and helping others. In this way, “Others” is not only about receiving support, but also about giving it, reinforcing resilience in both directions [

2].

Social support through various means, such as general support, caregiver support, relationships, peer support and social networks, have all been shown to improve outcomes in CKD/ESKD and PD. General social support has been associated with better self-management of CKD [

20] and lower mortality and reduction in risk of technique failure in patients on PD [

26]. Such support is also associated with decreased depressive symptoms, increased recovery rates, and better outcomes after trauma [

27,

28]. Having a supportive caregiver enhances the quality-of-life of patients on hemodialysis [

29] and strong supportive relationships with family, friends, and healthcare professionals improve the empowerment of patients on PD [

4]. Moreover, in a review of 12 articles, peer support was shown to improve treatment adherence, boost self-efficacy, and strengthen engagement in care [

30]. These social relationships are key to building resilience and maintaining health in patients with ESKD. Finally in one study of over 500 patients on dialysis, patients on PD had larger networks, more types of relationships and received more social support than HD patients. Those patients with larger social networks had higher participation-seeking preferences and lower anxiety, while closer and more satisfying relationships were associated with better psychological well-being [

31].

3.1.4. Wellness Flexibility

The final pillar, Wellness Flexibility, is about learning to adapt both mentally and physically to constant changes in one’s life [

2]. Patients living with chronic illnesses often have to deal with setbacks, unexpected changes, and adjustments to routine. For patients on PD, flexibility and adaptability are essential to overall wellbeing. Since patients on PD must work their lives around their condition, they have to adjust schedules, sleep, travel, and work around treatment timing.

Having mental and emotional adaptability in chronic illness is incredibly important because of the clear relationship between mental illness and chronic disease, specifically CKD and ESKD. Evidence shows that the prevalence of depression is likely higher in Patients on PD than in the general population (31%, 37.8%, 39% in 3 cohort) [

32,

33,

34]. Depressive symptoms increased significantly with CKD stage and high depression and anxiety scores were associated with an inferior QOL in patients with kidney disease [

32,

33]. Symptoms of depression are associated with decreased survival and increased likelihood of technique failure in patients on PD [

34].

Similarly, having good physical health and adaptability is crucial to positive outcomes in CKD and ESKD. Many patients on PD (63%) and HD (71%) are sedentary (<5000 steps/day) [

35], and lack of exercise may exacerbate comorbidities, such as hypertension, diabetes mellitus, coronary artery disease and depressive mood disorders (with ESKD) [

36]. In addition, in patients with CKD, frailty status was associated with higher risk of cardiovascular events and mortality [

37], whereas higher self-reported physical activity was associated with lower risk of cardiovascular events including stroke, myocardial infarction, heart failure, and mortality in CKD patients [

38]. Regular exercise can combat some of these risks in patients with ESKD. For example, intradialytic exercise intervention was effective in reducing the level of fatigue in outpatients undergoing dialysis [

39] and, generally, exercise decreases depression and lowers blood pressure, decreases fatigue and improves cardio pulmonary parameters (with ESRD) [

40].

Therefore, this part of the GROW model encourages patients to be physically and mentally flexible and adaptable to change by taking care of their emotional and physical health. Other elements of wellness flexibility, especially in the emotional health component, include accepting one’s current state, creative problem solving, and utilizing strategies such as humor and gratitude to cope with adversity.

4. Applying the GROW Model to Support Resilience in PD

Understanding the GROW framework provides a valuable foundation, but the goal is to apply these principles to support patients in building and maintaining their resilience. The following section explores how each domain can be actively developed to strengthen resilience in PD patients (

Table 1).

4.1. Strengthen Good Emotions

How can physicians and medical professionals help strengthen Good Emotions in patients on PD? One of the easiest and most impactful ways to strengthen resilience in PD patients is by fostering optimism and gratitude. Start by helping patients understand that optimism is a mindset, not just a feeling. When patients are encouraged to focus on what is manageable, they feel more hopeful and motivated to engage in care. Patients who viewed optimism as a choice reported changing their behaviors and feeling more in control of their illness [

45]. Optimism in patients is also enhanced when clinicians share realistically optimistic outcomes. Providers’ optimism improves patient coping and self-management [

46].

Simple gratitude practices can also make a difference. Patients can be encouraged to keep a gratitude journal, write weekly thank-you notes, or reflect on their personal strengths. These small habits are linked to better mood, improved immune function, reduced anxiety, and even lower inflammation [

41]. Helping patients to steer away from negative thoughts and to focus on what is good in their lives can build the emotional strength patients need to keep moving forward.

4.2. Find Reason and Purpose

How can the medical team help patients on PD find their

Reason and Purpose? One way to help PD patients build resilience is by reconnecting them with what gives their life meaning. For many people on PD, daily routines can become consumed by treatment, making it harder to focus on the “why” behind their efforts. The multidisciplinary medical team can help patients identify their core values and set purposeful goals, big and small, through strategies such as behavioral activation. For example, one can encourage a patient to write down simple activities they enjoy, schedule them once a week and then reflect on successes and challenges with a clinical team member [

47]. Examples of activities might be listening to music, attending a community event, or revisiting a hobby or creative outlet. Studies have shown that creating clarity around values and purpose is linked to better self-management, and utilizing tools like motivational interviewing or mobile apps designed to support engagement can improve self-efficacy, management and clinical outcomes [

4,

45,

46,

47]. Patients may benefit from brief conversations about what they hope to accomplish and what matters to them most—whether caring for family, continuing work, or finding spiritual meaning.

4.3. Build Social Networks

How can the health care team encourage patients on PD to develop their Relationships with Others? For patients on PD, the isolation of managing a chronic illness can take an emotional and physical toll. Strengthening social connection starts with simple steps: joining a support group, participating in a faith or community group, or even reaching out to ask for help. Encouraging patients to reflect on their relationships, improve communication, and work through conflicts can deepen connection and emotional safety. Patients may also benefit from putting efforts into directly helping others through volunteer work or random acts of kindness. PD patients can be a source of inspiration and guidance to those earlier in their PD journey. They can also help others through practices like loving-kindness meditation or active listening which can further build social connection. These interventions can benefit the patients and their social networks and can help build the patient’s own resilience and sense of purpose [

2].

4.4. Develop Wellness Flexibility

How can the health care team help promote Wellness Flexibility in the mental and physical health of patients on PD? Wellness flexibility is being able to adapt emotionally and physically when challenges to health and life occur. For people living with chronic illness, especially those on PD, routines can be interrupted, setbacks happen, and plans need to change. Helping patients recognize this kind of flexibility starts with small, manageable strategies. Setting “bite-size” goals can create momentum and reinforce a sense of progress. Working with a health coach can also strengthen self-efficacy and confidence, especially when facing changes in health or treatment routines [

2].

To prioritize emotional health, physicians and their teams can assess patients for mood changes and refer for psychological and behavioral health treatment. This can begin with screening for depression and anxiety and treating or referring to counseling services. Mental health professionals can help patients tackle cognitive distortions by helping them to reflect on challenges, identify negative thoughts and self-doubt and replace them with realistic thoughts [

10]. They can also help patients to practice acceptance and see change as opportunity for growth. Techniques like mindfulness, acceptance, and reframing negative thoughts are powerful tools and over time can help patients endure adversity and lead to meaningful personal growth [

48].

Physicians and their teams can also help patients care for and improve their physical health. They can encourage and prescribe regular exercise for patients with CKD and on HD/PD, refer to physical therapy for conditioning, strengthening and balance, and engage them with a nutritionist to optimize nutritional intake of healthy foods. Clinicians may also consider energy management education (EME), which is a fatigue management approach that uses practical strategies (prioritizing, using efficient body postures, organizing home environments) to manage daily life energy expenditure [

49], which may improve fatigue in pts on HD. Even small shifts in mindset and physical health can improve outcomes and give patients the flexibility they need to manage the ups and downs of chronic illness.

5. Measuring Resilience

Despite the GROW framework and interventions, resilience is difficult to measure. It is multidimensional, a mix of thoughts, feelings, and behaviors that can change over time and in different situations. What resilience looks like can vary between people and even for one person across a lifespan and between different chronic illnesses. Having a tool to quantify resilience and its components could help providers identify patients at risk, track progress over time, and tailor interventions to better support patients as they face the challenges of chronic illness. Several tools have been developed to measure dimensions of resilience. One is the Connor–Davidson Resilience Scale (CD-RISC), a 25-item self-report questionnaire originally developed for adults in clinical practice [

50]. It assesses five core dimensions: personal competence, tolerance of stress, acceptance of change and secure relationships, a sense of control, and spiritual influence. Shorter 10-item and 2-item versions exist for use in time-constrained settings. For a more targeted assessment, the Brief Resilience Scale (BRS) uses just six items to measure an individual’s ability to bounce back from stress [

51]. The Mount Sinai Resilience Scale was developed as a 24-item self-report tool designed to measure not just inherent traits, but specific thoughts and behaviors that support resilience [

52]. Each item highlights a mindset or action that can be cultivated to promote resilience.

Quality of life is measured routinely in ESKD patients with the Kidney Disease Quality of Life tool (KDQOL). This is a 36-item self-reported health survey that targets patients with CKD and ESKD patients, in areas such as burden of disease, functional capacity, sleep habits, quality of social interaction, sexual function, cognitive function and work status [

53]. While the KDQOL is not designed to measure resilience directly, it is a widely used tool in kidney care that captures several domains closely tied to resilience, such as emotional well-being, social support, and symptom burden.

As we continue to better understand the role of resilience in chronic illness, one next step is finding ways to make it a routine part of care for patients on PD. This starts with an ongoing assessment of resilience akin to other metrics tracked in dialysis patients. Incorporating the MSRS along with the KDQOL could help identify patients who are struggling as well as which aspects of resilience need attention by utilizing the frameworks previously discussed. Longitudinal data could help us understand how resilience impacts survival, quality of life, and treatment adherence in PD patients. Once identified, these patients can be offered support through multi-disciplinary targeted, resilience-building interventions.

6. Discussion

Resilience is the ability to bounce back or adapt after adversity which is a critical factor for patients living with chronic illness, especially those on PD. Throughout this paper, we explored how resilience influences a patient’s ability to manage the emotional and psychological challenges of PD, while also touching on physical and logistical demands that contribute to overall well-being in this patient population. As a part of the GROW framework, resilience can be described in four broad domains: good emotions (optimism, gratitude), reason and purpose (self-efficacy, meaning), others and social connection (giving and receiving support), and wellness flexibility (emotional and physical adaptability). Each of these domains is supported by evidence linking them to improved outcomes in patients with CKD and ESKD.

Multiple studies have shown that resilience affects more than just how patients feel, it influences how they function. Instruments like the CD-RISC, BRS and the MSRS allow us to assess the core psychological components of resilience more directly. The KDQOL additionally adds data on emotional well-being, social support and symptom burden. Used together, these measurement tools can give providers a clearer understanding of how patients are coping and where they may need additional support, creating opportunities for more targeted, multidisciplinary interventions that address specific gaps in resilience. In addition, evidence-based strategies, such as initiating a gratitude practice or using motivational interviewing can be implemented to improve well-being and resilience and, in turn, improve patient outcomes in ESKD and specifically those on PD.

Limitations of this paper include the following. This review is exploratory in nature and draws on multiple sources across different patient populations, with limited direct research on resilience specifically in PD patients. Authors did not conduct a systematic review for this manuscript. Many of the psychological frameworks and measurement tools discussed, including the MSRS and CD-RISC, have not yet been widely validated in ESKD populations, and are being extrapolated to PD settings. Additionally, much of the existing literature including studies examining hope and adjustment, KDQOL-based quality of life comparisons, and the initial MSRS validation are cross-sectional in design. This limits our ability to understand how resilience develops or fluctuates over time and makes it difficult to draw definitive cause and effect conclusions about its long-term impact on outcomes like survival or treatment adherence. These gaps highlight the need for future research that applies and tests resilience models longitudinally, particularly in PD patients.

7. Conclusions

As we continue to better understand the role of resilience in chronic illness, the next step is finding ways to make it a routine part of care for patients on PD. This starts with assessing resilience longitudinally. Using the MSRS alongside existing tools like the KDQOL could help clinicians identify patients who are struggling, not just with dialysis itself, but with the emotional and psychological demands that come with it. These tools can help pinpoint which areas of resilience may need the most support and development, such as strengthening realistic optimism, social connection, or a sense of meaning and purpose.

Future work could include research in integrating resilience assessments into routine care across different treatment modalities allowing us to understand how resilience develops in different dialysis settings and the differential impacts of treatments on quality of life and the components of resilience. Comparing PD and IHD patients using tools like the MSRS and KDQOL could highlight important differences in patient experience and guide more personalized, multi-disciplinary interventions. In the long run, making resilience part of everyday dialysis care has the potential to improve not only emotional well-being, but also adherence and long-term treatment outcomes.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, L.P., P.D., H.K. and N.A.-d.S.; Methodology, L.P., P.D., H.K. and N.A.-d.S.; Investigation, L.P. and N.A.-d.S.; Data Curation, L.P. and N.A.-d.S.; Writing—Original Draft Preparation, L.P., P.D. and N.A.-d.S.; Writing—Review and Editing, L.P., P.D., H.K. and N.A.-d.S.; Visualization, L.P., P.D., H.K. and N.A.-d.S.; Supervision, L.P., P.D. and H.K.; Project Administration, L.P., P.D. and H.K. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest related to this work.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| CKD | Chronic Kidney Disease |

| ESKD | End Stage Kidney Disease |

| PD | Peritoneal Dialysis |

| IHD | Incenter Hemodialysis |

| CD-RISC | Connor–Davidson Resilience Scale |

| BRS | Brief Resilience Scale |

| MSRS | Mount Sinai Resilience Scale |

| KDQOL | Kidney Disease Quality of Life tool |

References

- Billington, E.; Simpson, J.; Unwin, J.; Bray, D.; Giles, D. Does hope predict adjustment to end-stage renal failure and consequent dialysis? Br. J. Health Psychol. 2008, 13, 683–699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peccoralo, L.A.; Mehta, D.H.; Schiller, G.; Logio, L.S. The Health Benefits of Resilience. In Nutrition, Fitness, and Mindfulness: An Evidence-Based Guide for Clinicians; Uribarri, J., Vassalotti, J.A., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; pp. 189–201. [Google Scholar]

- Teitelbaum, I. Peritoneal Dialysis. N. Engl. J. Med. 2021, 385, 1786–1795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baumgart, A.; Manera, K.E.; Johnson, D.W.; Craig, J.C.; Shen, J.I.; Ruiz, L.; Wang, A.Y.-M.; Yip, T.; Fung, S.K.S.; Tong, M.; et al. Meaning of empowerment in peritoneal dialysis: Focus groups with patients and caregivers. Nephrol. Dial. Transplant. 2020, 35, 1949–1958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, P.K.-T.; Chow, K.M. Peritoneal Dialysis Patient Selection: Characteristics for Success. Adv. Chronic Kidney Dis. 2009, 16, 160–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Budhram, B.; Sinclair, A.; Komenda, P.; Severn, M.; Sood, M.M. A Comparison of Patient-Reported Outcome Measures of Quality of Life By Dialysis Modality in the Treatment of Kidney Failure: A Systematic Review. Can. J. Kidney Health Dis. 2020, 7, 2054358120957431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, E.A.; Blake, P.G.; Boudville, N.; Davies, S.; De Arteaga, J.; Dong, J.; Finkelstein, F.; Foo, M.; Hurst, H.; Johnson, D.W.; et al. International Society for Peritoneal Dialysis practice recommendations: Prescribing high-quality goal-directed peritoneal dialysis. Perit. Dial. Int. J. Int. Soc. Perit. Dial. 2020, 40, 244–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blake, P.G.; Quinn, R.R.; Oliver, M.J. Peritoneal Dialysis and the Process of Modality Selection. Perit. Dial. Int. J. Int. Soc. Perit. Dial. 2013, 33, 233–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fissell, R.B. Peritoneal Dialysis: Psychosocial Adaptations and Burnout. In Complications in Dialysis; Fadem, S.Z., Moura-Neto, J.A., Golper, T.A., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2023; pp. 277–280. [Google Scholar]

- Nataatmadja, M.; Evangelidis, N.; Manera, K.E.; Cho, Y.; Johnson, D.W.; Craig, J.C.; Baumgart, A.; Hanson, C.S.; Shen, J.; Guha, C.; et al. Perspectives on mental health among patients receiving dialysis. Nephrol. Dial. Transplant. 2021, 36, 1317–1325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Southwick, S.M.; Charney, D.S.; DePierro, J.M. Resilience: The Science of Mastering Life’s Greatest Challenges, 3rd ed.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Seligman, M.E.P. Flourish: A Visionary New Understanding of Happiness and Well-Being; Simon & Schuster: New York, NY, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Noghan, N.; Akaberi, A.; Pournamdarian, S.; Borujerdi, E.; Sadat Hejazi, S. Resilience and therapeutic regimen compliance in patients undergoing hemodialysis in hospitals of Hamedan, Iran. Electron. Physician 2018, 10, 6853–6858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, L.-C.; Chang, H.-J.; Liu, Y.-M.; Hsieh, H.-L.; Lo, L.; Lin, M.-Y.; Lu, K.-C. The Relationship between Health-Promoting Behaviors and Resilience in Patients with Chronic Kidney Disease. Sci. World J. 2013, 2013, 124973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glover, L.M.; Butler-Williams, C.; Cain-Shields, L.; Forde, A.T.; Purnell, T.S.; Young, B.; Sims, M. Optimism is associated with chronic kidney disease and rapid kidney function decline among African Americans in the Jackson Heart Study. J. Psychosom. Res. 2020, 139, 110267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kutner, N.G.; Zhang, R.; McClellan, W.M.; Cole, S.A. Psychosocial predictors of non-compliance in haemodialysis and peritoneal dialysis patients. Nephrol. Dial. Transplant. 2002, 17, 93–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Musich, S.; Wang, S.S.; Kraemer, S.; Hawkins, K.; Wicker, E. Purpose in Life and Positive Health Outcomes Among Older Adults. Popul. Health Manag. 2018, 21, 139–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, E.S.; Tkatch, R.; Martin, D.; Macleod, S.; Sandy, L.; Yeh, C. Resilient Aging: Psychological Well-Being and Social Well-Being as Targets for the Promotion of Healthy Aging. Gerontol. Geriatr. Med. 2021, 7, 23337214211002951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campbell, Z.C.; Dawson, J.K.; Kirkendall, S.M.; McCaffery, K.J.; Jansen, J.; Campbell, K.L.; Lee, V.W.; Webster, A.C. Interventions for improving health literacy in people with chronic kidney disease. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2022, 2022, CD012026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perales-Montilla, C.M.; Duschek, S.; Reyes-Del Paso, G.A. The influence of emotional factors on the report of somatic symptoms in patients on chronic haemodialysis: The importance of anxiety. Nefrologia 2013, 33, 816–825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Timmers, L.; Thong, M.; Dekker, F.W.; Boeschoten, E.W.; Heijmans, M.; Rijken, M.; Weinman, J.; Kaptein, A. Illness perceptions in dialysis patients and their association with quality of life. Psychol. Health 2008, 23, 679–690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, S.F.V.; Wang, T.J.; Liang, S.Y.; Lin, L.J.; Lu, Y.Y.; Lee, M.C. Differences in self-care knowledge, self-efficacy, psychological distress and self-management between patients with early- and end-stage chronic kidney disease. J. Clin. Nurs. 2022, 31, 2287–2295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korzh, O.; Titkova, A.; Fylenko, Y.; Lavrova, Y. Evaluation of health-promoting self-care behaviors in hypertensive patients with concomitant chronic kidney disease in primary care. Prim. Health Care Res. Dev. 2022, 23, e48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, F.H.F.; Newman, S.; Khan, B.A.; Griva, K. The role of subjective cognitive complaints in self-management among haemodialysis patients: A cross-sectional study. BMC Nephrol. 2022, 23, 363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, F.H.F.; Newman, S.; Khan, B.A.; Griva, K. Prevalence and trajectories of subjective cognitive complaints and implications for patient outcomes: A prospective study of haemodialysis patients. Br. J. Health Psychol. 2023, 28, 651–671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szeto, C.-C.; Chow, K.-M.; Kwan, B.C.-H.; Law, M.-C.; Chung, K.-Y.; Leung, C.-B.; Li, P.K.-T. The Impact of Social Support on the Survival of Chinese Peritoneal Dialysis Patients. Perit. Dial. Int. J. Int. Soc. Perit. Dial. 2008, 28, 252–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- King, L.A.; King, D.W.; Fairbank, J.A.; Keane, T.M.; Adams, G.A. Resilience-recovery factors in post-traumatic stress disorder among female and male Vietnam veterans: Hardiness, postwar social support, and additional stressful life events. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 1998, 74, 420–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tsai, J.; Harpaz-Rotem, I.; Pietrzak, R.H.; Southwick, S.M. The Role of Coping, Resilience, and Social Support in Mediating the Relation Between PTSD and Social Functioning in Veterans Returning from Iraq and Afghanistan. Psychiatry Interpers. Biol. Process. 2012, 75, 135–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.C.; Chang, L.C.; Liu, C.Y.; Ho, Y.F.; Weng, S.C.; Tsai, T.I. The Roles of Social Support and Health Literacy in Self-Management Among Patients With Chronic Kidney Disease. J. Nurs. Scholarsh. 2018, 50, 265–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Longley, R.M.; Harnedy, L.E.; Ghanime, P.M.; Arroyo-Ariza, D.; Deary, E.C.; Daskalakis, E.; Sadang, K.G.; West, J.; Huffman, J.C.; Celano, C.M.; et al. Peer support interventions in patients with kidney failure: A systematic review. J. Psychosom. Res. 2023, 171, 111379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neumann, D.; Lamprecht, J.; Robinski, M.; Mau, W.; Girndt, M. Social relationships and their impact on health-related outcomes in peritoneal versus haemodialysis patients: A prospective cohort study. Nephrol. Dial. Transplant. 2018, 33, 1235–1244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mok, M.M.Y.; Liu, C.K.M.; Lam, M.F.; Kwan, L.P.Y.; Chan, G.C.W.; Ma, M.K.M.; Yap, D.Y.H.; Chiu, F.; Choy, C.B.Y.; Tang, S.C.W.; et al. A Longitudinal Study on the Prevalence and Risk Factors for Depression and Anxiety, Quality of Life, and Clinical Outcomes in Incident Peritoneal Dialysis Patients. Perit. Dial. Int. J. Int. Soc. Perit. Dial. 2019, 39, 74–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pu, L.; Zou, Y.; Wu, S.-K.; Wang, F.; Zhang, Y.; Li, G.-S.; Wang, J.-W.; Zhang, L.-X.; Zhao, M.-H.; Wang, L. Prevalence and associated factors of depressive symptoms among chronic kidney disease patients in China: Results from the Chinese Cohort Study of Chronic Kidney Disease (C-STRIDE). J. Psychosom. Res. 2020, 128, 109869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, J.; Ye, H.; Yi, C.; Li, J.; Yu, X.; Zhu, L.; Zhang, X.; Wu, X.; Mao, H.; Yu, X.; et al. The negative impact of depressive symptoms on patient and technique survival in peritoneal dialysis: A prospective cohort study. Int. Urol. Nephrol. 2020, 52, 2393–2401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cobo, G.; Gallar, P.; Gama-Axelsson, T.; Di Gioia, C.; Qureshi, A.R.; Camacho, R.; Vigil, A.; Heimbürger, O.; Ortega, O.; Rodriguez, I.; et al. Clinical determinants of reduced physical activity in hemodialysis and peritoneal dialysis patients. J. Nephrol. 2015, 28, 503–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, S.H.; Do, J.Y.; Lee, S.-Y.; Kim, J.C. Effect of dialysis modality on frailty phenotype, disability, and health-related quality of life in maintenance dialysis patients. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0176814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hannan, M.; Chen, J.; Hsu, J.; Zhang, X.; Saunders, M.R.; Brown, J.; McAdams-DeMarco, M.; Mohanty, M.J.; Vyas, R.; Hajjiri, Z.; et al. Frailty and Cardiovascular Outcomes in Adults With CKD: Findings From the Chronic Renal Insufficiency Cohort (CRIC) Study. Am. J. Kidney Dis. 2024, 83, 208–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruinius, J.W.; Hannan, M.; Chen, J.; Brown, J.; Kansal, M.; Meza, N.; Saunders, M.R.; He, J.; Ricardo, A.C.; Lash, J.P.; et al. Self-reported Physical Activity and Cardiovascular Events in Adults With CKD: Findings From the CRIC (Chronic Renal Insufficiency Cohort) Study. Am. J. Kidney Dis. 2022, 80, 751–761.e751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samuel Raj, V.V.; Mangalvedhe, P.V.; Shetty, M.S.; Balakrishnan, D.C. Impact of Exercise on Fatigue in Patients Undergoing Dialysis in a Tertiary Care Hospital. Cureus 2023, 15, e35004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afsar, B.; Siriopol, D.; Aslan, G.; Eren, O.C.; Dagel, T.; Kilic, U.; Kanbay, A.; Burlacu, A.; Covic, A.; Kanbay, M. The impact of exercise on physical function, cardiovascular outcomes and quality of life in chronic kidney disease patients: A systematic review. Int. Urol. Nephrol. 2018, 50, 885–904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seligman, M.E.P.; Steen, T.A.; Park, N.; Peterson, C. Positive Psychology Progress: Empirical Validation of Interventions. Am. Psychol. 2005, 60, 410–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghozali, M.T.; Satibi, S.; Forthwengel, G. The impact of mobile health applications on the outcomes of patients with chronic kidney disease: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Med. Life 2023, 16, 1299–1309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lunardi, L.E.; Hill, K.; Xu, Q.; Le Leu, R.; Bennett, P.N. The effectiveness of patient activation interventions in adults with chronic kidney disease: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Worldviews Evid.-Based Nurs. 2023, 20, 238–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, W.R.; Rollnick, S. Motivational Interviewing: Helping People Change; Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Gardenhire, J.; Mullet, N.; Fife, S. Living With Parkinson’s: The Process of Finding Optimism. Qual. Health Res. 2019, 29, 1781–1793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freeman-Hildreth, Y.; Aron, D.; Cola, P.A.; Wang, Y. Coping with diabetes: Provider attributes that influence type 2 diabetes adherence. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0214713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stein, A.T.; Carl, E.; Cuijpers, P.; Karyotaki, E.; Smits, J.A.J. Looking beyond depression: A meta-analysis of the effect of behavioral activation on depression, anxiety, and activation. Psychol. Med. 2021, 51, 1491–1504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tedeschi, R.G.; Calhoun, L.G. The Posttraumatic Growth Inventory: Measuring the positive legacy of trauma. J. Trauma. Stress 1996, 9, 455–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farragher, J.F.; Polatajko, H.J.; McEwen, S.; Jassal, S.V. A Proof-of-Concept Investigation of an Energy Management Education Program to Improve Fatigue and Life Participation in Adults on Chronic Dialysis. Can. J. Kidney Health Dis. 2020, 7, 2054358120916297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Connor, K.M.; Davidson, J.R.T. Development of a new resilience scale: The Connor-Davidson Resilience Scale (CD-RISC). Depress. Anxiety 2003, 18, 76–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, B.W.; Dalen, J.; Wiggins, K.; Tooley, E.; Christopher, P.; Bernard, J. The brief resilience scale: Assessing the ability to bounce back. Int. J. Behav. Med. 2008, 15, 194–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Depierro, J.M.; Marin, D.B.; Sharma, V.; Katz, C.L.; Pietrzak, R.H.; Feder, A.; Murrough, J.W.; Starkweather, S.; Marx, B.P.; Southwick, S.M.; et al. Development and initial validation of the Mount Sinai Resilience Scale. Psychol. Trauma Theory Res. Pract. Policy 2024, 16, 407–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hays, R.D.; Kallich, J.D.; Mapes, D.L.; Coons, S.J.; Carter, W.B. Development of the kidney disease quality of life (KDQOL™) instrument. Qual. Life Res. 1994, 3, 329–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).