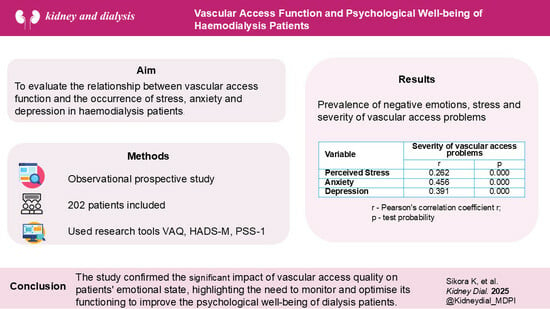

Vascular Access Function and Psychological Well-Being of Haemodialysis Patients

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Subject

2.2. Inclusion Criteria

2.3. Methods, Techniques, Research Tools

2.4. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Characteristics of the Study Group

3.2. Problems Related to Vascular Access

3.3. Perceived Stress, Anxiety and Depression

3.4. Correlation of Negative Emotions and Vascular Access Related Problems

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Białobrzeska, B. Nursing problems associated with depression in patients treated with renal replacement. Ren. Dis. Transplant. Forum. 2013, 6, 177–185. [Google Scholar]

- Kuciel-Lewandowska, J.M.; Laber, W.Z.; Kierzek, A.; Paprocka-Borowicz, M. Assessment of the Level of Anxiety and Depression in Patients Before Cardiac Rehabilitation. Pielęgniarstwo Zdr. Publiczne 2015, 5, 247–251. [Google Scholar]

- Jaeschke, R.; Siwek, M.; Grabski, B.; Dudek, D. Współwystępowanie zaburzeń depresyjnych i lękowych. Psychiatria 2010, 7, 189–197. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, D.H.; Park, J.I.; Lee, J.P.; Kim, Y.L.; Kang, S.W.; Yang, C.W.; Kim, N.H.; Kim, Y.S.; Lim, C.S. The effects of vascular access types on the survival and quality of life and depression in the incident hemodialysis patients. Ren. Fail. 2020, 42, 30–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.T.; Wu, M.; Xie, Q.L.; Zhang, L.P.; Lu, W.; Pan, M.J.; Yan, X.W.; Zhang, L.; Zhang, L.; Wang, Y. The association between vascular access satisfaction and quality of life and depression in maintained hemodialysis patients. J. Vasc. Access 2022, 25, 439–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afsar, B.; Elsurer, R.; Covic, A.; Kanbay, M. Vascular Access Type, Health-Related Quality of Life, and Depression in Hemodialysis Patients: A Preliminary Report. J. Vasc. Access 2012, 13, 215–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cukor, D.; Coplan, J.; Brown, C.; Friedman, S.; Newville, H.; Safier, M.; Spielman, L.A.; Peterson, R.A.; Kimmel, P.L. Anxiety Disorders in Adults Treated by Hemodialysis: A Single-Center Study. Am. J. Kidney Dis. 2008, 52, 128–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cukor, D.; Coplan, J.; Brown, C.; Friedman, S.; Cromwell-Smith, A.; Peterson, R.A.; Kimmel, P.L. Depression and anxiety in urban hemodialysis patients. Clin. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. CJASN 2007, 2, 484–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ćwiek, A.; Czok, M.; Kurczab, B.; Kramarczyk, K.; Drzyzga, K.; Kucia, K. Association Between Depression And Hemodialysis In Patients With Chronic Kidney Disease. Psychiatr. Danub. 2017, 29, 499–503. [Google Scholar]

- Najafi, A.; Keihani, S.; Bagheri, N.; Ghanbari Jolfaei, A.; Mazaheri Meybodi, A. Association Between Anxiety and Depression With Dialysis Adequacy in Patients on Maintenance Hemodialysis. Iran. J. Psychiatry Behav. Sci. 2016, 10, e4962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feldman, H.I.; Kobrin, S.; Wasserstein, A. Hemodialysis vascular access morbidity. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 1996, 7, 523–535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rodak, S. Our everyday—Dialysis as seen through the eyes of dialysis nurse. Ren. Dis. Transplant. Forum. 2013, 6, 186–194. [Google Scholar]

- Wiśniewska, L.; Paczkowska, B.; Białobrzeska, B. Zapotrzebowanie na wsparcie emocjonalne wśród pacjentów leczonych nerkozastępczo. Ren. Dis. Transplant. Forum. 2010, 3, 63–70. [Google Scholar]

- De Walden-Gałuszko, K.; Majkowicz, M. Model Oceny Jakości Opieki Paliatywnej Realizowanej w Warunkach Stacjonarnych; Zakład Medycyny Paliatywnej AMG Gdańsk: Gdańsk, Poland, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Kozieł, P.; Lomper, K.; Uchmanowicz, B.; Polański, J. Związek akceptacji choroby oraz lęku i depresji z oceną jakości życia pacjentek z chorobą nowotworową gruczołu piersiowego. Med. Paliatywna W Prakt. 2016, 10, 28–36. [Google Scholar]

- Ślusarska, B.; Lalik, S.; Kulina, D.; Zarzycka, D. Nasilenie odczuwanego stresu w grupie pacjentów z nadciśnieniem tętniczym oraz jego związek z samokontrolą leczenia choroby. Arter. Hypertens. 2013, 17, 369–376. [Google Scholar]

- Juczyński, Z.; Ogińska-Bulik, N. Narzędzia Pomiaru Stresu i Radzenia Sobie ze Stresem; Pracownia Testów Psychologicznych Polskiego Towarzystw Psychologicznego: Warsaw, Poland, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Ibrahim, M.B.; Abdelaal Badawi, S.E.; Alameri, R.A. Assessment of Pain and Anxiety During Arteriovenous Fistula Cannulation Among Hemodialysis Patients: A Cross-Sectional Study in Saudi Arabia. J. Multidiscip. Health 2022, 15, 705–718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Soponaru, C.; Bojian, A.; Iorga, M. Stress, coping mechanisms and quality of life in hemodialysis patients. Arch. Med. Sci.-Civiliz. Dis. 2016, 1, 16–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hao, W.; Tang, Q.; Huang, X.; Ao, L.; Wang, J.; Xie, D. Analysis of the prevalence and influencing factors of depression and anxiety among maintenance dialysis patients during the COVID-19 pandemic. Int. Urol. Nephrol. 2021, 53, 1453–1461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qawaqzeh, D.T.A.; Masa’deh, R.; Hamaideh, S.H.; Alkhawaldeh, A.; ALBashtawy, M. Factors affecting the levels of anxiety and depression among patients with end-stage renal disease undergoing hemodialysis. Int. Urol. Nephrol. 2023, 55, 2887–2896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Büberci, R.; Sirali, S.K.; Duranay, M. The Relationship Between Vascular Access Type and Sleep Quality, Anxiety, Depression in Hemodialysis Patients. Available online: http://turkjnephrol.org/en/the-relationship-between-vascular-access-type-and-sleep-quality-anxiety-depression-in-hemodialysis-patients-137107 (accessed on 31 August 2023).

- Çora, A.R.; Çelik, E. Association between vascular access type and depression in hemodialysis patients. Hemodial. Int. 2023, 27, 296–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brito, D.C.S.D.; Machado, E.L.; Reis, I.A.; Carmo, L.P.D.F.D.; Cherchiglia, M.L. Depression and anxiety among patients undergoing dialysis and kidney transplantation: A cross-sectional study. Sao Paulo Med. J. 2019, 137, 137–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Espahbodi, F.; Hosseini, H.; Mirzade, M.M.; Shafaat, A.B. Effect of Psycho Education on Depression and Anxiety Symptoms in Patients on Hemodialysis. Iran. J. Psychiatry Behav. Sci. 2015, 9, e227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lilympaki, I.; Makri, A.; Vlantousi, K.; Koutelekos, I.; Babatsikou, F.; Polikandrioti, M. Effect of Perceived Social Support on The Levels of Anxiety and Depression of Hemodialysis Patients. Mater. Socio-Medica 2016, 28, 361–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| How Much Have the Following Vascular Access Issues Bothered You in the Last 4 Weeks? Circle the Number That Best Describes Your Situation. | Not at All | A Little | Moderately | Quite a Bit | Extremely |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pain | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| Bleeding | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| Swelling | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| Bruising | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| Redness | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| Infection | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| Clotting | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| Appearance of your access | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| Worries about whether your access is working well to clean the blood properly | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| Having to come early to the dialysis unit because of your access | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| Having to come early to the dialysis unit because of your access | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| Problems sleeping because of your access | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| Having to be careful to protect your access | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| Your access interfering with your daily activities (e.g., work or other regular daily activities) | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| Your access interfering with your social and leisure activities | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| Worries about being hospitalised because of problems with your access | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| Worries about being hospitalised because of problems with your access | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| Variable | n | % | M | SD | Me | Min | Max | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 202 | - | 52.78 | 16.52 | 51 | 21 | 92 | |

| Sex | Men | 105 | 51.98 | |||||

| Female | 97 | 48.02 | ||||||

| Type of Vascular Access | Arteriovenous Fistula (AVF) | 134 | 66.34 | |||||

| Tunnelled Central Venous Catheter (CVC) | 58 | 28.71 | ||||||

| Non-Tunnelled Central Venous Catheter (CVC) | 5 | 2.48 | ||||||

| Arteriovenous Graft (AVG) | 5 | 2.48 |

| Variable | n | M | SD | Me | Min | Max | Shapiro–Wilk Test | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| S-W | p | |||||||

| Severity of vascular access problems | 202 | 13.79 | 11.22 | 11 | 0 | 62 | 0.892 | 0.000 |

| Variable | n | M | SD | Me | Min | Max | Shapiro–Wilk Test | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| S-W | p | |||||||

| Perceived Stress | 202 | 23.69 | 4.46 | 24 | 0 | 32 | 0.85 | 0.000 |

| Variable | n | M | SD | Me | Min | Max | Shapiro–Wilk Test | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| S-W | p | |||||||

| Anxiety | 202 | 8.57 | 4.81 | 8 | 0 | 20 | 0.979 | 0.004 |

| Depression | 202 | 6.79 | 5.02 | 7 | 0 | 20 | 0.944 | 0.000 |

| Variable | Severity of Vascular Access Problems | |

|---|---|---|

| r | p | |

| Perceived Stress | 0.262 | 0.000 |

| Anxiety | 0.456 | 0.000 |

| Depression | 0.391 | 0.000 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Sikora, K.; Łuczyk, R.J.; Zwolak, A.; Wawryniuk, A.; Łuczyk, M. Vascular Access Function and Psychological Well-Being of Haemodialysis Patients. Kidney Dial. 2025, 5, 34. https://doi.org/10.3390/kidneydial5030034

Sikora K, Łuczyk RJ, Zwolak A, Wawryniuk A, Łuczyk M. Vascular Access Function and Psychological Well-Being of Haemodialysis Patients. Kidney and Dialysis. 2025; 5(3):34. https://doi.org/10.3390/kidneydial5030034

Chicago/Turabian StyleSikora, Kamil, Robert Jan Łuczyk, Agnieszka Zwolak, Agnieszka Wawryniuk, and Marta Łuczyk. 2025. "Vascular Access Function and Psychological Well-Being of Haemodialysis Patients" Kidney and Dialysis 5, no. 3: 34. https://doi.org/10.3390/kidneydial5030034

APA StyleSikora, K., Łuczyk, R. J., Zwolak, A., Wawryniuk, A., & Łuczyk, M. (2025). Vascular Access Function and Psychological Well-Being of Haemodialysis Patients. Kidney and Dialysis, 5(3), 34. https://doi.org/10.3390/kidneydial5030034