A Retrospective Cohort Study to Determine COVID-19 Mortality, Survival Probability and Risk Factors Among Children in a South African Province

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design, Setting and Participants

2.2. Sampling

2.3. Data Collection and Management

2.4. Sociodemographics and Clinical Manifestation in the Study

2.5. Study Outcome

2.6. Data Analysis

2.7. Ethical Considerations

3. Results

3.1. Study Participant Characteristics

3.2. Pediatric Patients with COVID-19 Clinical Manifestation in This Study

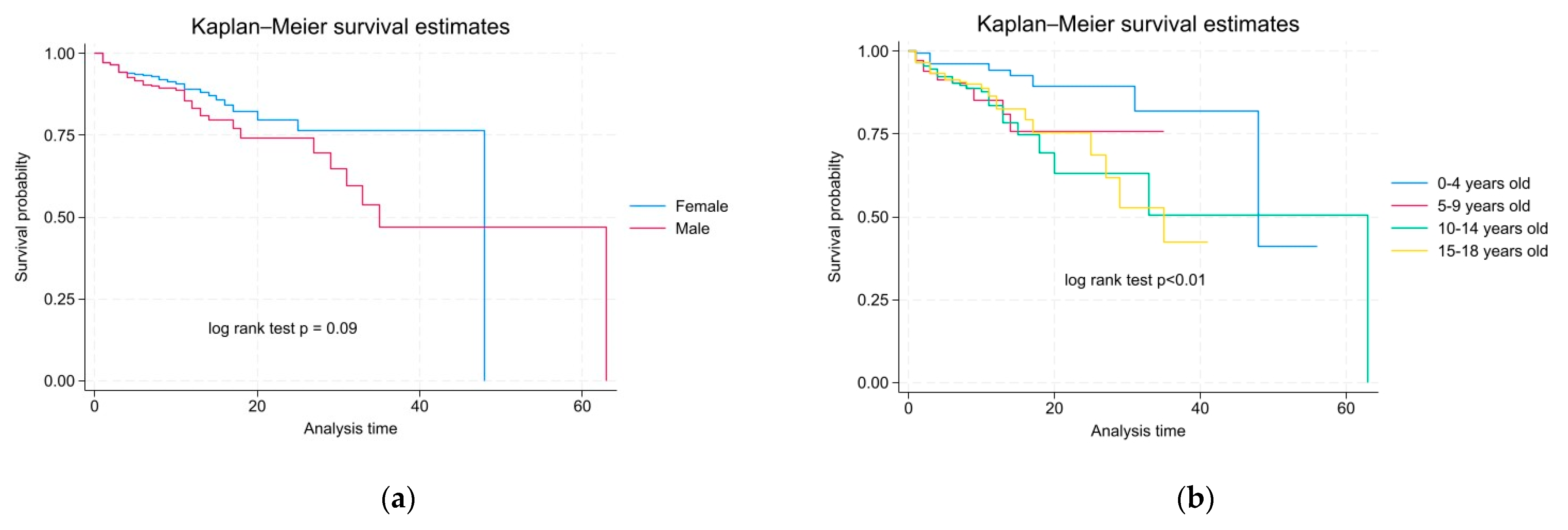

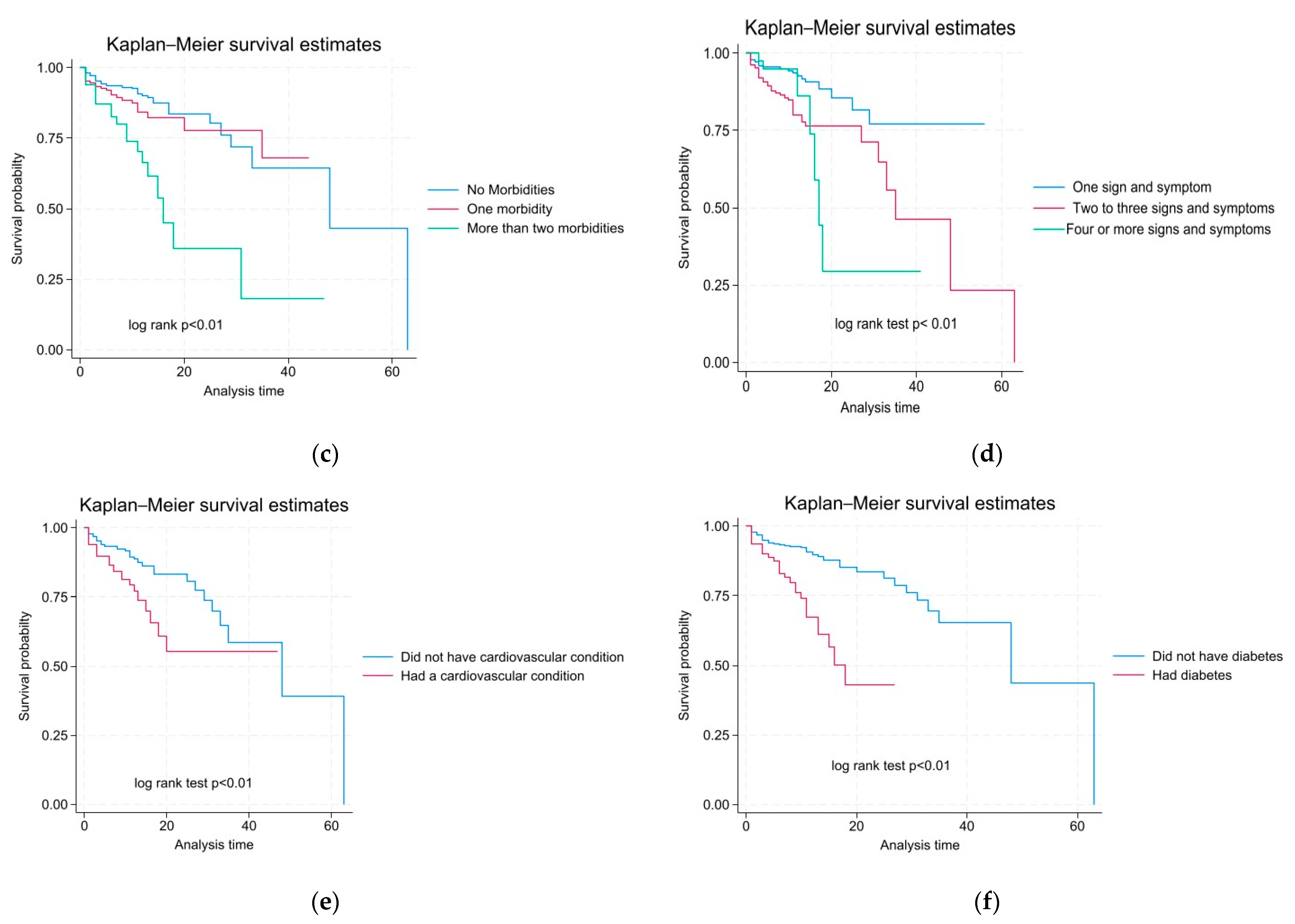

3.3. The Mortality Rate According to Characteristics and Survival Probability Among Pediatric Patients in This Study

3.4. Risk Factors of Time to Death in the Current Study

4. Discussion

4.1. Clinical Manifestations Observed in Patients Participating in the Study

4.2. Risk Factors Influencing Time to Death Among Study Participants

4.3. Study Strengths and Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Factors | Crude HR | p-Value | 95% Confidence Interval | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 5–9 years old | 2.63 | 0.01 * | 1.30–5.32 |

| 10–14 years old | 2.94 | <0.01 * | 1.56–5.56 | |

| 15–18 years old | 2.79 | <0.01 * | 1.49–5.25 | |

| Gender | Male | 2.32 | 0.02 * | 1.00–2.11 |

| Number of morbidities | One morbidity | 1.40 | 0.08 | 0.95–2.34 |

| ≥2 morbidities | 3.42 | <0.01 * | 2.13–5.50 | |

| Number of signs and symptoms | 1–3 Symptoms | 2.71 | <0.01 * | 1.77–4.16 |

| ≥4 Symptoms | 2.68 | 0.01 | 1.27–5.66 | |

| Immune-compromised | Yes | 1.00 | 0.99 | 0.41–2.44 |

| Cardiovascular conditions | Yes | 2.13 | <0.00 * | 1.42–3.20 |

| Lung-related condition | Yes | 2.01 | 0.17 | 0.47–5.47 |

| Diabetes | Yes | 3.30 | <0.00 * | 2.10–4.86 |

| Gastrointestinal condition | Yes | 0.87 | 0.81 | 0.28–2.74 |

| Fever and chills | Yes | 0.71 | 0.31 | 0.37–1.36 |

| Headache | Yes | 0.93 | 0.80 | 0.54–1.61 |

| Runny nose and congestion | Yes | 1.26 | 0.48 | 0.66–2.42 |

| Cough | Yes | 1.44 | 0.06 | 0.98–2.10 |

| New/loss of taste and smell | Yes | 0.95 | 0.89 | 0.44–2.04 |

| Muscular pain | Yes | 1.15 | 0.67 | 0.60–2.21 |

| Nausea/vomiting | Yes | 1.00 | 1.00 | 0.25–4.04 |

| Fatigue | Yes | 2.84 | <0.00 * | 1.71–4.71 |

| Short of breath | Yes | 3.10 | <0.00 * | 2.10–4.56 |

| Sore throat | Yes | 1.30 | 0.43 | 0.68–2.50 |

| Factors | Crude HR | p-Value | 95% Confidence Interval | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Morbidities | Yes | 1.72 | 0.11 | 0.88–3.36 |

| Morbidities | 1 morbidity | 0.53 | 0.23 | 0.19–1.48 |

| ≥2 morbidities | 0.71 | 0.72 | 0.10–4.79 | |

| Immune-compromised | Yes | 0.89 | 0.86 | 0.25–3.13 |

| Cardiovascular conditions | Yes | 1.08 | 0.87 | 0.40–2.91 |

| Lung-related condition | Yes | 1.37 | 0.60 | 0.43–4.42 |

| Diabetes | Yes | 1.83 | 0.24 | 0.66–5.07 |

| Gastrointestinal condition | Yes | 0.64 | 0.52 | 0.16–2.55 |

| Fever and chills | Yes | 0.37 | 0.01 * | 0.18–0.77 |

| Headache | Yes | 0.50 | 0.04 * | 0.26–0.95 |

| Runny nose and congestion | Yes | 1.28 | 0.52 | 0.61–2.69 |

| Cough | Yes | 0.66 | 0.08 | 0.41–1.06 |

| New/loss of taste and smell | Yes | 0.70 | 0.43 | 0.29–1.69 |

| Muscular pain | Yes | 0.75 | 0.45 | 0.36–1.57 |

| Nausea/vomiting | Yes | 0.90 | 0.89 | 0.21–3.87 |

| Fatigue | Yes | 1.43 | 0.24 | 0.79–2.60 |

| Short of breath | Yes | 1.55 | 0.11 | 0.91–2.65 |

| Sore throat | Yes | 0.90 | 0.80 | 0.42–1.95 |

References

- Sawicka, B.; Aslan, I.; Della Corte, V.; Periasamy, A.; Krishnamurthy, S.K.; Mohammed, A.; Said, M.M.T.; Saravanan, P.; Del Gaudio, G.; Adom, D.; et al. The coronavirus global pandemic and its impacts on society. In Coronavirus Drug Discovery; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2022; pp. 267–311. Available online: https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/B9780323851565000377 (accessed on 21 December 2023).

- Hiscott, J.; Alexandridi, M.; Muscolini, M.; Tassone, E.; Palermo, E.; Soultsioti, M.; Zevini, A. The global impact of the coronavirus pandemic. Cytokine Growth Factor. Rev. 2020, 53, 1–9. Available online: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/32487439 (accessed on 21 December 2023). [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization. WHO Coronavirus (COVID-19) Dashboard. 2025. Available online: https://covid19.who.int/ (accessed on 12 January 2026).

- McCormick, D.W.; Richardson, L.C.; Young, P.R.; Viens, L.J.; Gould, C.V.; Kimball, A.; Pindyck, T.; Rosenblum, H.G.; Siegel, D.A.; Vu, Q.M.; et al. Deaths in Children and Adolescents Associated with COVID-19 and MIS-C in the United States. Pediatrics 2021, 148, e2021052273. Available online: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/34385349 (accessed on 21 December 2023). [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gonzalez-Dambrauskas, S.; Vasquez-Hoyos, P.; Camporesi, A.; Cantillano, E.M.; Dallefeld, S.; Dominguez-Rojas, J.; Francoeur, C.; Gurbanov, A.; Mazzillo-Vega, L.; Shein, S.L.; et al. Paediatric critical COVID-19 and mortality in a multinational prospective cohort. Lancet Reg. Health Am. 2022, 12, 100272. Available online: https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S2667193X22000898 (accessed on 7 January 2026). [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Flaxman, S.; Whittaker, C.; Semenova, E.; Rashid, T.; Parks, R.M.; Blenkinsop, A.; Unwin, H.J.T.; Mishra, S.; Bhatt, S.; Gurdasani, D.; et al. Assessment of COVID-19 as the Underlying Cause of Death Among Children and Young People Aged 0 to 19 Years in the US. JAMA Netw. Open 2023, 6, e2253590. Available online: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/36716029 (accessed on 21 December 2023). [CrossRef]

- Treskova-Schwarzbach, M.; Haas, L.; Reda, S.; Pilic, A.; Borodova, A.; Karimi, K.; Koch, J.; Nygren, T.; Scholz, S.; Schönfeld, V.; et al. Pre-existing health conditions and severe COVID-19 outcomes: An umbrella review approach and meta-analysis of global evidence. BMC Med. 2021, 19, 212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kompaniyets, L.; Agathis, N.T.; Nelson, J.M.; Preston, L.E.; Ko, J.Y.; Belay, B.; Pennington, A.F.; Danielson, M.L.; DeSisto, C.L.; Chevinsky, J.R.; et al. Underlying Medical Conditions Associated With Severe COVID-19 Illness Among Children. JAMA Netw. Open 2021, 4, e2111182. Available online: https://jamanetwork.com/journals/jamanetworkopen/fullarticle/2780706 (accessed on 21 December 2023). [CrossRef]

- Mamishi, S.; Pourakbari, B.; Mehdizadeh, M.; Navaeian, A.; Eshaghi, H.; Yaghmaei, B.; Sadeghi, R.H.; Poormohammadi, S.; Mahmoudieh, Y.; Mahmoudi, S. Children with SARS-CoV-2 infection during the novel coronaviral disease (COVID-19) outbreak in Iran: An alarming concern for severity and mortality of the disease. BMC Infect. Dis. 2022, 22, 382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farrar, D.S.; Drouin, O.; Moore Hepburn, C.; Baerg, K.; Chan, K.; Cyr, C.; Donner, E.J.; Embree, J.E.; Farrell, C.; Forgie, S.; et al. Risk factors for severe COVID-19 in hospitalized children in Canada: A national prospective study from March 2020–May 2021. Lancet Reg. Health Am. 2022, 15, 100337. Available online: https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S2667193X22001545 (accessed on 21 December 2023). [CrossRef]

- Zhang, B.; Wu, Q.; Jhaveri, R.; Zhou, T.; Becich, M.J.; Bisyuk, Y.; Blanceró, F.; Chrischilles, E.A.; Chuang, C.H.; Cowell, L.G.; et al. Long COVID associated with SARS-CoV-2 reinfection among children and adolescents in the omicron era (RECOVER-EHR): A retrospective cohort study. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coughtrey, A.; Pereira, S.M.P.; Ladhani, S.; Shafran, R.; Stephenson, T. Long COVID in children and young people: Then and now. Curr. Opin. Infect. Dis. 2025, 38, 487–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashmawy, R.; Hammouda, E.A.; El-Maradny, Y.A.; Aboelsaad, I.; Hussein, M.; Uversky, V.N.; Redwan, E.M. Interplay between Comorbidities and Long COVID: Challenges and Multidisciplinary Approaches. Biomolecules 2024, 14, 835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adu-Amankwaah, J. Behind the shadows: Bringing the cardiovascular secrets of long COVID into light. Eur. J. Prev. Cardiol. 2025, 32, 499–501. Available online: https://academic.oup.com/eurjpc/article/32/6/499/7619333 (accessed on 14 January 2026). [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kwok, K.O.; Huang, Y.; Tsoi, M.T.F.; Tang, A.; Wong, S.Y.S.; Wei, W.I.; Hui, D.S.C. Epidemiology, clinical spectrum, viral kinetics and impact of COVID-19 in the Asia-Pacific region. Respirology 2021, 26, 322–333. Available online: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/33690946 (accessed on 21 December 2023). [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Melo, M.M.; Neta, M.M.R.; Neto, A.R.S.; Carvalho, A.R.B.; Magalhães, R.L.B.; Valle, A.R.M.C.; Ferreira, J.H.L.; Aliaga, K.M.J.; Moura, M.E.B.; Freitas, D.R.J. Symptoms of COVID-19 in children. Braz. J. Med. Biol. Res. 2022, 55, 1–7. Available online: http://www.scielo.br/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S0100-879X2022000100305&tlng=en (accessed on 21 December 2023). [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vidya, G.; Kalpana, M.; Roja, K.; Nitin, J.A.; Taranikanti, M. Pathophysiology and Clinical Presentation of COVID-19 in Children: Systematic Review. Mædica A J. Clin. Med. 2021, 16, 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, S.; Lai, L.Y.; Zhu, R.; Gao, Y.; Zhao, Z. Prevalence and duration of common symptoms in people with long COVID: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Glob. Health 2025, 15, 04282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galindo, R.; Chow, H.; Rongkavilit, C. COVID-19 in Children. Pediatr. Clin. N. Am. 2021, 68, 961–976. Available online: https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S003139552100081X (accessed on 21 December 2023). [CrossRef]

- Mohtasham-Amiri, Z.; Keihanian, F.; Rad, E.H.; Shakib, R.J.; Vahed, L.K.; Kouchakinejad–Eramsadati, L.; Rezvani, S.M.; Nikkar, R. Long- COVID and general health status in hospitalized COVID-19 survivors. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 8116. Available online: https://www.nature.com/articles/s41598-023-35413-z (accessed on 21 December 2023). [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.J.; Feng, Y.J.; Chen, J.; Li, B.; Luo, Z.C.; Wang, P.X. Clinical Features of Fatalities in Patients With COVID-19. Disaster Med. Public Health Prep. 2021, 15, e9–e11. Available online: https://www.cambridge.org/core/product/identifier/S1935789320002359/type/journal_article (accessed on 21 December 2023). [CrossRef]

- Katikireddi, S.V.; Hainey, K.J.; Beale, S. The Impact of Covid-19 on Different Population Subgroups: Ethnic, Gender and Age-Related Disadvantage. J. R. Coll. Physicians Edinb. 2021, 51, 40–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khowa, T.; Cimi, A.; Mukasi, T. Socio-economic impact of COVID-19 on rural livelihoods in Mbashe Municipality. Jàmbá J. Disaster Risk Stud. 2022, 14, 8. Available online: https://jamba.org.za/index.php/jamba/article/view/1361 (accessed on 19 December 2023). [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shafi, M.; Liu, J.; Jian, D.; Rahman, I.U.; Chen, X. Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on rural communities: A cross-sectional study in the Sichuan Province of China. BMJ Open 2021, 11, e046745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Statistics South Africa. Census 2022 in Brief. Pretoria. 2024. Available online: https://www.statssa.gov.za/publications/Census2022inBrief/Census2022inBriefJune2024.pdf (accessed on 13 January 2026).

- National Institute for Communicable Disease. Latest Confirmed Cases of COVID-19 in South Africa (18 November 2021). 2021. Available online: https://www.nicd.ac.za/latest-confirmed-cases-of-covid-19-in-south-africa-18-november-2021/#:~:text=Table_title:%20LATEST%20CONFIRMED%20CASES%20OF%20COVID%2D19%20IN,122%20386%20%7C%20Percentage%20total:%204%2C2%20%7C (accessed on 13 January 2026).

- Gupta, V.; Singh, A.; Ganju, S.; Singh, R.; Thiruvengadam, R.; Natchu, U.C.M.; Gupta, N.; Kaushik, D.; Chanana, S.; Sharma, D.; et al. Severity and mortality associated with COVID-19 among children hospitalised in tertiary care centres in India: A cohort study. Lancet Reg. Health Southeast Asia 2023, 13, 100203. Available online: https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S277236822300063X (accessed on 7 January 2026). [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shamsi, F.; Karimi, M.; Nafei, Z.; Akbarian, E. Survival and Mortality in Hospitalized Children with COVID-19: A Referral Center Experience in Yazd, Iran. Can. J. Infect. Dis. Med. Microbiol. 2023, 2023, 5205188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsankov, B.K.; Allaire, J.M.; Irvine, M.A.; Lopez, A.A.; Sauvé, L.J.; Vallance, B.A.; Jacobson, K. Severe COVID-19 Infection and Pediatric Comorbidities: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Int. J. Infect. Dis. 2021, 103, 246–256. Available online: https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S1201971220324759 (accessed on 7 January 2026). [CrossRef]

- Giugni, F.R.; Duarte-Neto, A.N.; da Silva, L.F.F.; Monteiro, R.A.A.; Mauad, T.; Saldiva, P.H.N.; Dolhnikoff, M. Younger age is associated with cardiovascular pathological phenotype of severe COVID-19 at autopsy. Front. Med. 2024, 10, 1327415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Z.; Wang, J.; Ullah, R.; Chen, M.; Huang, K.; Dong, G.; Fu, J. Covid 19 and diabetes in children: Advances and strategies. Diabetol. Metab. Syndr. 2024, 16, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flores-Cisneros, L.; Gutiérrez-Vargas, R.; Escondrillas-Maya, C.; Zaragoza-Jiménez, C.; Rodríguez, G.G.; López-Gatell, H.; Islas, D.G. Risk factors for severe disease and mortality in children with COVID-19. Heliyon 2024, 10, e23629. Available online: https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S2405844023108371 (accessed on 7 January 2026). [CrossRef]

- Oliveira, E.A.; Mak, R.H.; Colosimo, E.A.; Mendonça, A.C.Q.; Vasconcelos, M.A.; Martelli-Júnior, H.; Silva, L.R.; Oliveira, M.C.L.; Pinhati, C.C.; e Silva, A.C.S. Risk factors for COVID-19-related mortality in hospitalized children and adolescents with diabetes mellitus: An observational retrospective cohort study. Pediatr. Diabetes 2022, 23, 763–772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roshanzamir, Z.; Mohammadi, F.; Yadegar, A.; Naeini, A.M.; Hojabri, K.; Shirzadi, R. An Overview of Pediatric Pulmonary Complications During COVID-19 Pandemic: A Lesson for Future. Immun. Inflamm. Dis. 2024, 12, e70049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kehoe, K.; Morden, E.; Zinyakatira, N.; Heekes, A.; Jones, H.E.; Walter, S.R.; Jacobs, T.; Murray, J.; Buys, H.; Redaniel, M.T.; et al. Lower respiratory tract infection admissions and deaths among children under 5 years in public sector facilities in the Western Cape Province, South Africa, before and during the COVID-19 pandemic (2019–2021). S. Afr. Med. J. 2024, 114, e1560. Available online: https://samajournals.co.za/index.php/samj/article/view/1560 (accessed on 7 January 2026). [CrossRef]

- Kronbichler, A.; Kresse, D.; Yoon, S.; Lee, K.H.; Effenberger, M.; Shin, J.I. Asymptomatic patients as a source of COVID-19 infections: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Int. J. Infect. Dis. 2020, 98, 180–186. Available online: https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S1201971220304872 (accessed on 7 January 2026). [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harwood, R.; Yan, H.; Talawila Da Camara, N.; Smith, C.; Ward, J.; Tudur-Smith, C.; Linney, M.; Clark, M.; Whittaker, E.; Saatci, D.; et al. Which children and young people are at higher risk of severe disease and death after hospitalisation with SARS-CoV-2 infection in children and young people: A systematic review and individual patient meta-analysis. eClinicalMedicine 2022, 44, 101287. Available online: https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S2589537022000177 (accessed on 7 January 2026). [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shafaei, B.; Nafei, Z.; Karimi, M.; Behniafard, N.; Shamsi, F.; Faisal, M.; Shahbaz, A.P.A.; Akbarian, E. Which Groups of Children Are at More Risk of Fatality during COVID-19 Pandemic? A Case-Control Study in Yazd, Iran. Can. J. Infect. Dis. Med. Microbiol. 2023, 2023, 8838056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martin, B.; DeWitt, P.E.; Russell, S.; Anand, A.; Bradwell, K.R.; Bremer, C.; Gabriel, D.; Girvin, A.T.; Hajagos, J.G.; McMurry, J.A.; et al. Characteristics, Outcomes, and Severity Risk Factors Associated with SARS-CoV-2 Infection Among Children in the US National COVID Cohort Collaborative. JAMA Netw. Open 2022, 5, e2143151. Available online: https://jamanetwork.com/journals/jamanetworkopen/fullarticle/2788844 (accessed on 23 December 2023).

- Zhang, J.; Dong, X.; Liu, G.; Gao, Y. Risk and Protective Factors for COVID-19 Morbidity, Severity, and Mortality. Clin. Rev. Allergy Immunol. 2022, 64, 90–107. Available online: https://link.springer.com/10.1007/s12016-022-08921-5 (accessed on 23 December 2023). [CrossRef]

- Tsabouri, S.; Makis, A.; Kosmeri, C.; Siomou, E. Risk Factors for Severity in Children with Coronavirus Disease 2019: A Comprehensive Literature Review. Pediatr. Clin. N. Am. 2021, 68, 321–338. Available online: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/33228941 (accessed on 12 December 2023). [CrossRef]

- da Rosa Mesquita, R.; Francelino Silva Junior, L.C.; Santos Santana, F.M.; Farias de Oliveira, T.; Campos Alcântara, R.; Monteiro Arnozo, G.; da Silva Filho, E.R.; Galdino Dos Santos, A.G.; Oliveira da Cunha, E.J.; Salgueiro de Aquino, S.H.; et al. Clinical manifestations of COVID-19 in the general population: Systematic review. In Wiener Klinische Wochenschrift; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2021; Volume 133, pp. 377–382. [Google Scholar]

- Zheng, Y.B.; Zeng, N.; Yuan, K.; Tian, S.S.; Yang, Y.B.; Gao, N.; Chen, X.; Zhang, A.-Y.; Kondratiuk, A.L.; Shi, P.-P.; et al. Prevalence and risk factor for long COVID in children and adolescents: A meta-analysis and systematic review. J. Infect. Public Health 2023, 16, 660–672. Available online: https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S1876034123000710 (accessed on 23 December 2023). [CrossRef]

- Zhou, G.Y.; Penwill, N.Y.; Cheng, G.; Singh, P.; Cheung, A.; Shin, M.; Nguyen, M.; Mittal, S.; Burrough, W.; Spad, M.-A.; et al. Utility of illness symptoms for predicting COVID-19 infections in children. BMC Pediatr. 2022, 22, 655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sampaio Rocha-Filho, P.A. Headache associated with COVID-19: Epidemiology, characteristics, pathophysiology, and management. Headache J. Head Face Pain 2022, 62, 650–656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DiSabella, M.; Pierce, E.; McCracken, E.; Ratnaseelan, A.; Vilardo, L.; Borner, K.; Langdon, R.; Fletcher, A.A. Pediatric Headache Experience During the COVID-19 Pandemic. J. Child. Neurol. 2022, 37, 871–881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caronna, E.; Pozo-Rosich, P. Headache as a Symptom of COVID-19: Narrative Review of 1-Year Research. Curr. Pain Headache Rep. 2021, 25, 73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallardo, V.J.; Shapiro, R.E.; Caronna, E.; Pozo-Rosich, P. The relationship of headache as a symptom to COVID-19 survival: A systematic review and meta-analysis of survival of 43,169 inpatients with COVID-19. Headache J. Head Face Pain 2022, 62, 1019–1028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variable | Frequency n | % |

|---|---|---|

| Age | ||

| 0–4 years old | 199 | 24% |

| 5–9 years old | 143 | 17% |

| 10–14 years old | 240 | 28% |

| 15–18 years old | 264 | 31% |

| Gender | ||

| Female | 505 | 60% |

| Male | 341 | 40% |

| Number of morbidities | ||

| No morbidities | 596 | 70% |

| 1 morbidity | 178 | 21% |

| ≥2 morbidities | 72 | 9% |

| Number of signs and symptoms | ||

| No symptom | 414 | 49% |

| 1–3 symptoms | 384 | 45% |

| ≥4 symptoms | 48 | 6% |

| Number of days before health outcome | ||

| 7 days or less | 432 | 51% |

| 8–14 days | 310 | 37% |

| 15–21 days | 55 | 7% |

| 22–28 days | 19 | 2% |

| 29 and more days | 30 | 6% |

| Morbidity | Total n (%) | Survived n (%) | Died n (%) | Mortality Rate Per 1000 Children (in Days) | p-Value a | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Immuno-compromised | No | 808 (96%) | 702 (96%) | 106 (96%) | 12.52 | 0.67 |

| Yes | 38 (4%) | 33 (4%) | 5 (4%) | 15.02 | ||

| Cardiovascular condition | No | 704 (83%) | 627 (85%) | 77 (69%) | 11.02 | <0.01 * |

| Yes | 142 (17%) | 108 (15%) | 34 (31%) | 21.58 | ||

| Lung-related condition | No | 831 (98%) | 724 (99%) | 107 (96%) | 12.64 | 0.27 |

| Yes | 15 (2%) | 11(1%) | 4 (4%) | 22.39 | ||

| Diabetes | No | 747 (88%) | 667 (91%) | 80 (72%) | 10.25 | <0.01 * |

| Yes | 99 (12%) | 68 (9%) | 31 (28%) | 33.92 | ||

| Gastrointestinal conditions | No | 821 (97%) | 713 (97%) | 108 (97%) | 12.82 | 0.95 |

| Yes | 25 (3%) | 22 (3%) | 3 (3%) | 12.93 | ||

| Morbidity | Total n (%) | Survived n (%) | Died n (%) | Mortality Rate Per 1000 Children (in Days) | p-Value a | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fever and chills | No | 741 (88%) | 640 (87%) | 101 (91%) | 13.28 | 0.40 |

| Yes | 105 (12%) | 95 (13%) | 10 (9%) | 9.68 | ||

| Headache | No | 722 (85%) | 626 (85%) | 96 (86%) | 13.36 | 0.36 |

| Yes | 124 (15%) | 109 (15%) | 15 (14%) | 9.58 | ||

| Runny nose and congestion | No | 787 (93%) | 686 (93%) | 101 (91%) | 12.63 | 0.95 |

| Yes | 59 (7%) | 49 (7%) | 10 (9%) | 14.98 | ||

| Cough | No | 583 (69%) | 515 (70%) | 68 (61%) | 11.45 | 0.12 |

| Yes | 263 (31%) | 220 (30%) | 43 (39%) | 15.72 | ||

| New/loss of taste and smell | No | 789 (93%) | 682 (93%) | 104 (94%) | 12.91 | 0.57 |

| Yes | 60 (7%) | 7 (6%) | 3 (3%) | 11.67 | ||

| Muscular pain | No | 783 (93%) | 682 (93%) | 101 (91%) | 12.60 | 0.58 |

| Yes | 63 (7%) | 53 (7%) | 10 (9%) | 15.36 | ||

| Nausea/vomiting | No | 830 (98%) | 721 (98%) | 109 (98%) | 12.74 | 0.65 |

| Yes | 16 (2%) | 14(2%) | 2 (2%) | 17.70 | ||

| Fatigue | No | 780 (93%) | 696 (95%) | 93 (84%) | 11.27 | <0.01 * |

| Yes | 57 (7%) | 39 (5%) | 18 (16%) | 38.65 | ||

| Shortness of breath | No | 710 (84%) | 639 (87%) | 71 (64%) | 10.40 | <0.01 * |

| Yes | 136 (16%) | 96 (13%) | 40 (36%) | 28.43 | ||

| Sore throat | No | 759 (90%) | 658 (90%) | 101 (91%) | 12.85 | 0.98 |

| Yes | 87 (10%) | 77 (10%) | 10 (9%) | 12.55 | ||

| Patient Characteristics | Total n (%) | Survived n (%) | Died n (%) | Mortality Rate Per 1000 Children (in Days) | p-Value a |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | |||||

| 0–4 years old | 199 (22%) | 186 (24%) | 13 (10%) | 5.73 | <0.01 |

| 5–9 years old | 143 (16%) | 123 (16%) | 20 (16%) | 15.83 | |

| 10–14 years old | 240 (26%) | 202 (26%) | 38 (30%) | 16.68 | |

| 15–18 years old | 332 (35%) | 277 (35%) | 55 (44%) | 15.46 | |

| Gender | |||||

| Female | 552 (60%) | 488 (62%) | 64 (51%) | 10.80 | 0.09 |

| Male | 362 (40%) | 300 (38%) | 62 (49%) | 15.78 | |

| Number of morbidities | |||||

| No morbidities | 662 (72%) | 594 (75%) | 68 (54%) | 10.11 | <0.01 |

| 1 morbidity | 181 (20%) | 147 (19%) | 34 (27%) | 13.27 | |

| ≥2 morbidities | 71(8%) | 47 (6%) | 24 (19%) | 35.97 | |

| Number of signs and symptoms | |||||

| No symptom | 434 (47%) | 403 (51%) | 31 (25%) | 7.23 | <0.01 |

| 1–3 symptoms | 416 (46%) | 334 (42%) | 82 (65%) | 18.76 | |

| ≥4 symptoms | 64 (7%) | 51 (6%) | 13 (10%) | 17.50 | |

| Number of days before outcome | |||||

| 7 days or less | 432 (51%) | 356 (48%) | 76 (68%) | 39.92 | <0.01 |

| 8–14 days | 310 (37%) | 289 (39%) | 21 (19%) | 6.27 | |

| 15–21 days | 55 (7%) | 49 (7%) | 6 (5%) | 6.51 | |

| 22–28 days | 19 (2%) | 17 (2%) | 2 (2%) | 4.26 | |

| 29 or days | 30 (4%) | 24 (3%) | 6 (5%) | 5.40 | |

| Factors | Adjusted HR | p-Value | 95% Confidence Interval | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 5–9 years old | 2.09 | 0.05 * | 1.01–4.31 |

| 10–14 years old | 2.24 | 0.02 * | 1.15–4.37 | |

| 15–18 years old | 2.25 | 0.02 * | 1.17–4.35 | |

| Gender | Male | 1.45 | 0.05 * | 1.00–2.18 |

| Signs and symptoms | 1–3 symptoms | 3.06 | <0.01 * | 1.51–6.44 |

| ≥4 symptoms | 6.40 | 0.01 * | 1.45–28.18 | |

| Fever and chills | Yes | 0.37 | 0.01 * | 0.18–0.77 |

| Headache | Yes | 0.50 | 0.04 * | 0.26–0.95 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Tantoh, A.L.A.; Mokoatle, M.C.; Mbonane, T.P. A Retrospective Cohort Study to Determine COVID-19 Mortality, Survival Probability and Risk Factors Among Children in a South African Province. COVID 2026, 6, 20. https://doi.org/10.3390/covid6010020

Tantoh ALA, Mokoatle MC, Mbonane TP. A Retrospective Cohort Study to Determine COVID-19 Mortality, Survival Probability and Risk Factors Among Children in a South African Province. COVID. 2026; 6(1):20. https://doi.org/10.3390/covid6010020

Chicago/Turabian StyleTantoh, Asongwe Lionel Ateh, Makhutsisa Charlotte Mokoatle, and Thokozani P. Mbonane. 2026. "A Retrospective Cohort Study to Determine COVID-19 Mortality, Survival Probability and Risk Factors Among Children in a South African Province" COVID 6, no. 1: 20. https://doi.org/10.3390/covid6010020

APA StyleTantoh, A. L. A., Mokoatle, M. C., & Mbonane, T. P. (2026). A Retrospective Cohort Study to Determine COVID-19 Mortality, Survival Probability and Risk Factors Among Children in a South African Province. COVID, 6(1), 20. https://doi.org/10.3390/covid6010020