Influence of Trust in Information Sources on Self-Rated Health Among Latino Day Laborers During the COVID-19 Pandemic

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Background

3.2. Recruitment

3.3. Measures

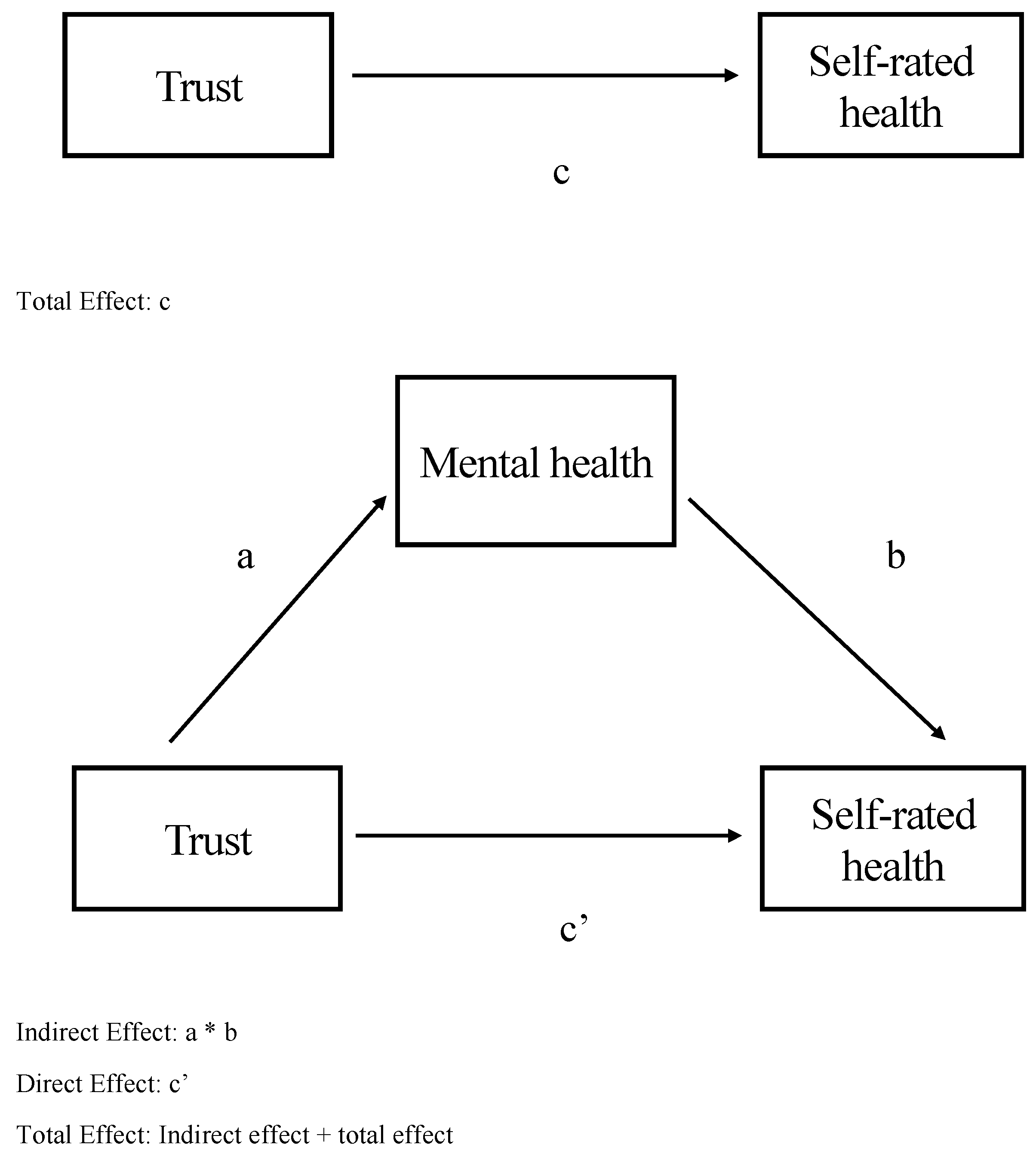

4. Data Analysis

5. Results

6. Discussion

6.1. Strengths

6.2. Limitations

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ou, J.Y.; Peters, J.L.; Levy, J.I.; Bongiovanni, R.; Rossini, A.; Scammell, M.K. Self-rated health and its association with perceived environmental hazards, the social environment, and cultural stressors in an environmental justice population. BMC Public Health 2018, 18, 970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Linton, S.L.; Leifheit, K.M.; McGinty, E.E.; Barry, C.L.; Pollack, C.E. Association between housing insecurity, psychological distress, and self-rated health among US adults during the COVID-19 pandemic. JAMA Netw. Open 2021, 4, e2127772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haro-Ramos, A.Y.; Rodriguez, H.P. Immigration policy vulnerability linked to adverse mental health among Latino day laborers. J. Immigr. Minor. Health 2022, 24, 842–852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. COVID Data Tracker. 2024. Available online: https://covid.cdc.gov/covid-data-tracker/#demographics (accessed on 9 June 2024).

- Olayo-Méndez, A.; Vidal De Haymes, M.; García, M.; Cornelius, L.J. Essential, disposable, and excluded: The experience of Latino immigrant workers in the US during COVID-19. J. Poverty 2021, 25, 612–628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolwowicz-Lopez, E.; Boniface, E.; Díaz-Anaya, S.; Cornejo-Torres, Y.; Darney, B.G. Awareness of the public charge, confidence in knowledge, and the use of public healthcare programs among Mexican-origin Oregon Latino/as. Int. J. Equity Health 2023, 22, 212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcini, L.M.; Pham, T.T.; Ambriz, A.M.; Lill, S.; Tsevat, J. COVID-19 diagnostic testing among underserved Latino communities: Barriers and facilitators. Health Soc. Care Community 2022, 30, e1907–e1916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castellon-Lopez, Y.M.; Carson, S.L.; Mansfield, L.; Garrison, N.A.; Barron, J.; Morris, D.; Ntekume, E.; Vassar, S.D.; Norris, K.C.; Brown, A.F.; et al. “The system doesn’t let us in”—A call for inclusive COVID-19 vaccine outreach rooted in Los Angeles Latinos’ experience of pandemic hardships and inequities. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 5785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Steel, K.C.; Fernandez-Esquer, M.E.; Atkinson, J.S.; Taylor, W.C. Exploring relationships among social integration, social isolation, self-rated health, and demographics among Latino day laborers. Ethn. Health 2018, 23, 425–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bombak, A.E. Self-rated health and public health: A critical perspective. Front. Public Health 2013, 1, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franks, P.; Gold, M.R.; Fiscella, K. Sociodemographics, self-rated health, and mortality in the US. Soc. Sci. Med. 2003, 56, 2505–2514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jylhä, M. What is self-rated health and why does it predict mortality? Towards a unified conceptual model. Soc. Sci. Med. 2009, 69, 307–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lommel, L.L.; Thompson, L.; Chen, J.L.; Waters, C.; Carrico, A. Acculturation, inflammation, and self-rated health in Mexican American immigrants. J. Immigr. Minor. Health 2019, 21, 1052–1060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vasquez Guzman, C.E.; Sanchez, G.R. The impact of acculturation and racialization on self-rated health status among US Latinos. J. Immigr. Minor. Health 2019, 21, 129–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, J.; Zheng, P.; Jia, Y.; Chen, H.; Mao, Y.; Chen, S.; Dai, J. Mental health problems and social media exposure during COVID-19 outbreak. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0231924. [Google Scholar]

- Schnittker, J.; Bacak, V. The increasing predictive validity of self-rated health. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e84933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nooteboom, B. Social capital, institutions, and trust. Rev. Soc. Econ. 2007, 65, 29–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pretty, J.; Ward, H. Social capital and the environment. World Dev. 2001, 29, 209–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- American Psychological Association. APA Dictionary of Psychology. 2024. Available online: https://dictionary.apa.org/trust (accessed on 9 June 2024).

- Yuan, H.; Long, Q.; Huang, G.; Huang, L.; Luo, S. Different roles of interpersonal trust and institutional trust in COVID-19 pandemic control. Soc. Sci. Med. 2022, 293, 114677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nieminen, T.; Martelin, T.; Koskinen, S.; Aro, H.; Alanen, E.; Hyyppä, M.T. Social capital as a determinant of self-rated health and psychological well-being. Int. J. Public Health 2010, 55, 531–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fell, L. Trust and covid-19: Implications for interpersonal, workplace, institutional, and information-based trust. Digit. Gov. Res. Pract. 2020, 2, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Shen, F. Exploring the impacts of media use and media trust on health behaviors during the COVID-19 pandemic in China. J. Health Psychol. 2022, 27, 1445–1461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomez-Aguinaga, B.; Oaxaca, A.L.; Barreto, M.A.; Sanchez, G.R. Spanish-language news consumption and Latino reactions to COVID-19. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 9629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, Y.; Hu, Q.; Grossman, S.; Basnyat, I.; Wang, P. Comparison of COVID-19 information seeking, trust of information sources, and protective behaviors in China and the US. J. Health Commun. 2021, 26, 657–666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vilar-Compte, M.; Gaitán-Rossi, P.; Félix-Beltrán, L.; Bustamante, A.V. Pre-COVID-19 social determinants of health among Mexican migrants in Los Angeles and New York City and their increased vulnerability to unfavorable health outcomes during the COVID-19 pandemic. J. Immigr. Minor. Health 2022, 24, 65–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jamieson, T.; Caldwell, D.; Gomez-Aguinaga, B.; Doña-Reveco, C. Race, ethnicity, nativity, and perceptions of health risk during the COVID-19 pandemic in the US. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 11113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magaña, D.; Durazo, A.; Ramos, L.; Matlock, T. An analysis of metaphor in COVID-19 TV news in English and Spanish. J. Commun. Healthc. 2023, 17, 254–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bermejo, F.; Reggi, L.; Tiribelli, S.; Zuckerman, E. Coverage of COVID-19 and Political Partisanship-Comparing Across Nations. Media Cloud. 2020. Available online: https://civic.mit.edu/index.html%3Fp=2771.html (accessed on 9 June 2024).

- Zhao, E.; Wu, Q.; Crimmins, E.M.; Ailshire, J.A. Media trust and infection mitigating behaviours during the COVID-19 pandemic in the USA. BMJ Glob. Health 2020, 5, e003323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pinna, M.; Picard, L.; Goessmann, C. Cable news and COVID-19 vaccine compliance. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 16804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jalan, M.; Riehm, K.; Agarwal, S.; Gibson, D.; Labrique, A.; Thrul, J. Burden of mental distress in the US associated with trust in media for COVID-19 information. Health Promot. Int. 2022, 37, daac162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patwary, M.M.; Bardhan, M.; Browning, M.H.E.M.; Disha, A.S.; Haque, M.d.Z.; Billah, S.M.; Kabir, M.P.; Hossain, M.R.; Alam, M.A.; Shuvo, F.K.; et al. Association between perceived trusted of COVID-19 information sources and mental health during the early stage of the pandemic in Bangladesh. Healthcare 2021, 10, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, H.; Singh, G.K. Monthly trends in self-reported health status and depression by race/ethnicity and socioeconomic status during the COVID-19 Pandemic, United States, April 2020–May 2021. Ann. Epidemiol. 2021, 63, 52–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Doan, L.N.; Chong, S.K.; Misra, S.; Kwon, S.C.; Yi, S.S. Immigrant Communities and COVID-19: Strengthening the Public Health Response. Am. J. Public Health 2021, 111, 224–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, S. Subjective well-being and mental health during the pandemic outbreak: Exploring the role of institutional trust. Res. Aging 2022, 44, 10–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldman-Mellor, S.; Plancarte, V.; Perez-Lua, F.; Payán, D.D.; De Trinidad Young, M.E. Mental health among rural Latino immigrants during the COVID-19 pandemic. SSM Ment. Health 2023, 3, 100177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galvan, T.; Lill, S.; Garcini, L.M. Another brick in the wall: Healthcare access difficulties and their implications for undocumented Latino/a immigrants. J. Immigr. Minor. Health 2021, 23, 885–894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcini, L.M.; Rosenfeld, J.; Kneese, G.; Bondurant, R.G.; Kanzler, K.E. Dealing with distress from the COVID-19 pandemic: Mental health stressors and coping strategies in vulnerable Latinx communities. Health Soc. Care Community 2022, 30, 284–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, K.F.; Simburger, D. Racial/ethnic residential segregation, poor self-rated health, and the moderating role of immigration. Race Soc. Probl. 2022, 14, 131–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marquez-Velarde, G.; Jones, N.E.; Keith, V.M. Racial stratification in self-rated health among Black Mexicans and White Mexicans. SSM Popul. Health 2020, 10, 100509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parra-Medina, D.; Calderon de Leon, E.; Vanegas, C.; McDaniel, M. Latinos and COVID-19 in Texas: A Social Determinants Perspective (Policy Brief 2022-01); Latino Research Institute, University of Texas at Austin: Austin, TX, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Pedraza, L.; Villela, R.; Kamatgi, V.; Cocuzzo, K.; Correa, R.; Lisigurski, M.Z. The impact of COVID-19 in the Latinx community. HCA Healthc. J. Med. 2022, 3, 97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramirez, G.; Ou, Y.; Saxton, R.; Miller, A.F.; Cuesta, M.M.; Meza, A.O.; Grieb, S.; Page, K.R.; Yang, C. Patterns of social, economic, and health challenges due to the COVID-19 pandemic experienced by Latino communities: A latent class analysis. J. Racial Ethn. Health Disparities 2025, in press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villatoro, A.P.; Wagner, K.M.; Salgado de Snyder, V.N.; Garcia, D.; Walsdorf, A.A.; Valdez, C.R. Economic and social consequences of COVID-19 and mental health burden among Latinx young adults during the 2020 pandemic. J. Latinx Psychol. 2022, 10, 25–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riley, A.R.; Chen, Y.H.; Matthay, E.C.; Glymour, M.M.; Torres, J.M.; Fernandez, A.; Bibbins-Domingo, K. Excess mortality among Latino people in California during the COVID-19 pandemic. SSM Popul. Health 2021, 15, 100860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, K.; Cassidy, J.; Mitchell, J.; Jones, S.; Jang, S.W. Documented barriers to health care access among Latinx older adults: A scoping review. Educ. Gerontol. 2023, 49, 81–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ornelas, I.J.; Ogedegbe, G. Listening to Latinx patient perspectives on COVID-19 to inform future prevention efforts. JAMA Netw. Open 2021, 4, e210737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prado, P.V.; Arechiga, C.; Marson, K.; Oviedo, Y.; Vizcaíno, T.; Gomez, M.; Alvarez, A.; Jimenez-Diecks, L.; Guevara, S.; Nava, A.; et al. Indications of digital literacy during Latino-focused, community-based COVID-19 testing implementation. JAMIA Open 2024, 7, ooae115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bastick, Z.; Mallet-Garcia, M. Double lockdown: The effects of digital exclusion on undocumented immigrants during the COVID-19 pandemic. New Media Soc. 2022, 24, 365–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Randall, J.G.; Dalal, D.K.; Dowden, A. Factors associated with contact tracing compliance among communities of color in the first year of the COVID-19 pandemic. Soc. Sci. Med. 2023, 322, 115814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayieko, S.A.; Atkinson, J.; Llamas, A.; Fernandez-Esquer, M.E. Coping with stress during the COVID-19 pandemic: Resilience and mental health among Latino day laborers. COVID 2024, 5, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levine, S.Z. Evaluating the seven-item Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale short-form: A longitudinal US community study. Soc. Psychiatry Psychiatr. Epidemiol. 2013, 48, 1519–1526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Perpiñá-Galvañ, J.; Cabañero-Martínez, M.J.; Richart-Martínez, M. Reliability and validity of shortened state-trait anxiety inventory in Spanish patients receiving mechanical ventilation. Am. J. Crit. Care 2013, 22, 46–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, S.; Kamarck, T.; Mermelstein, R.A. Global measure of perceived stress. J. Health Soc. Behav. 1983, 24, 385–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weaver, B.; Maxwell, H. Exploratory factor analysis and reliability analysis with missing data: A simple method for SPSS users. Quant. Methods Psychol. 2014, 10, 143–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kenny, D.A. SEM: Mediation. 2025. Available online: http://davidakenny.net/cm/mediate.htm (accessed on 26 October 2025).

- Hayes, A.F. An index and test of linear moderated mediation. Multivar. Behav. Res. 2015, 50, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hone, T.; Palladino, R.; Filippidis, F.T. Association of searching for health-related information online with self-rated health in the European Union. Eur. J. Public Health 2016, 26, 748–753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Levin, K.A. Study design III: Cross-sectional studies. Evid. Based Dent. 2006, 7, 24–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Variable | N | % | ||

| Marital status | ||||

| Single, never married | 128 | 47.2% | ||

| Married, living with a partner | 102 | 37.6% | ||

| Formerly married | 41 | 15.1% | ||

| Variable | Possible Range | Observed Range | M | SD |

| Age | 18.4–76.1 | 45.3 | 12.1 | |

| Years in the US | 1 month–59.3 years | 13.7 | 12.2 | |

| Years of school | 0–22.0 | 7.7 | 4.4 | |

| 30-day income | 0–2500.00 | 906.79 | 691.10 | |

| Trust | ||||

| Formal | 0–2.0 | 0–2.0 | 1.2 | 0.6 |

| Informal | 0–2.0 | 0–2.0 | 1.1 | 0.5 |

| Mental health | ||||

| Depression | 0–3.0 | 0–3.0 | 0.9 | 0.7 |

| Anxiety | 0–3.0 | 0–2.7 | 0.8 | 0.6 |

| Stress | 0–4.0 | 0–4.0 | 1.6 | 0.9 |

| Self-rated health | 0–4.0 | 0–4.0 | 1.9 | 1.3 |

| Trust Variable | No | Some | A Great Deal/A Lot of | Total Valid Cases | Not Applicable | Don’t Know | Refused | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CNN/CNN in Spanish | 33 | 100 | 70 | 203 | 52 | 15 | 1 | 271 |

| Valid % | 16.3% | 49.3% | 34.5% | 100.1% | - | - | - | - |

| Total % | 12.2% | 36.9% | 25.8% | - | 19.2% | 5.5% | 0.4% | 100.0% |

| Fox News/Fox | 42 | 85 | 65 | 192 | 61 | 18 | 0 | 271 |

| News in Spanish | ||||||||

| Valid % | 21.9% | 44.3% | 33.9% | 100.1% | - | - | - | - |

| Total % | 15.5% | 31.4% | 24.0% | - | 22.5% | 6.6% | 0.0% | 100.0% |

| Telemundo | 34 | 94 | 86 | 214 | 12 | 4 | 2 | 232 |

| Valid % | 15.9% | 43.9% | 40.2% | 100.0% | - | - | - | - |

| Total % | 14.7% | 40.5% | 37.1% | - | 5.2% | 1.7% | 0.9% | 100.1% |

| Univision | 26 | 95 | 100 | 221 | 10 | 1 | 0 | 232 |

| Valid % | 11.8% | 43.0% | 45.2% | 100.0% | - | - | - | - |

| Total % | 11.2% | 40.9% | 43.1% | - | 4.3% | 0.4% | 0.0% | 99.9% |

| Daily or weekly newspapers | 56 | 103 | 58 | 217 | 41 | 13 | 0 | 271 |

| Valid % | 25.8% | 47.5% | 26.7% | 100.0% | - | - | - | - |

| Total % | 20.7% | 38.0% | 21.4% | - | 15.1% | 4.8% | 0.0% | 100.0% |

| Radio stations | 53 | 120 | 73 | 246 | 22 | 3 | 0 | 271 |

| Valid % | 21.5% | 48.8% | 29.7% | 100.0% | - | - | - | - |

| Total % | 19.6% | 44.3% | 26.9% | - | 8.1% | 1.1% | 0.0% | 100.0% |

| Conversations with family | 33 | 97 | 138 | 268 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 271 |

| Valid % | 12.3% | 36.2% | 51.5% | 100.0% | - | - | - | - |

| Total % | 12.2% | 35.8% | 50.9% | - | 0.7% | 0.4% | 0.0% | 100.0% |

| Conversations with friends or coworkers | 59 | 116 | 95 | 270 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 271 |

| Valid % | 21.9% | 43.0% | 35.2% | 100.1% | - | - | - | - |

| Total % | 21.8% | 42.8% | 35.1% | - | 0.4% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 100.1% |

| Websites or online news sites | 56 | 109 | 61 | 226 | 34 | 10 | 1 | 271 |

| Valid % | 24.8% | 48.2% | 27.0% | 100.0% | - | - | - | - |

| Total % | 20.7% | 40.2% | 22.5% | - | 12.5% | 3.7% | 0.4% | 100.0% |

| Social media | 81 | 105 | 57 | 243 | 21 | 7 | 0 | 271 |

| Valid % | 33.3% | 43.2% | 23.5% | 100.0% | - | - | - | - |

| Total % | 29.9% | 38.7% | 21.0% | - | 7.7% | 2.6% | 0.0% | 99.9% |

| WhatsApp groups | 102 | 100 | 37 | 239 | 27 | 5 | 0 | 271 |

| Valid % | 42.7% | 41.8% | 15.5% | 100.0% | - | - | - | - |

| Total % | 37.6% | 36.9% | 13.7% | - | 10.0% | 1.8% | 0.0% | 100.0% |

| Model | Path (Figure 1) | B | 95% Confidence Interval |

|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1 | |||

| Total effect Formal trust → self-rated health | c (indirect + direct) | −0.327 | (−0.587, −0.068) |

| Formal trust → depression | A | 0.106 | (−0.042, 0.255) |

| Depression → self-rated health | B | −0.383 | (−0.591, −0.176) |

| Indirect effect | a * b | −0.041 | (−0.113, 0.025) |

| Direct effect | c’ | −0.287 | (−0.541, −0.032) |

| Model 2 | |||

| Total effect Formal trust → self-rated health | c (indirect+ direct) | −0.327 | (−0.587, −0.068) |

| Formal trust → anxiety | A | −0.046 | (−0.167, 0.074) |

| Anxiety → self-rated health | B | −0.487 | (−0.744, −0.231) |

| Indirect effect | a * b | 0.023 | (−0.035, 0.093) |

| Direct effect | c’ | −0.350 | (−0.604, −0.096) |

| Model 3 | |||

| Total effect Formal trust → self-rated health | c (indirect + direct) | −0.327 | (−0.587, −0.068) |

| Formal trust → stress | A | 0.040 | (−0.152, 0.233) |

| Stress → self-rated health | B | −0.156 | (−0.0319, 0.007) |

| Indirect effect | a * b | −0.006 | (−0.051, 0.029) |

| Direct effect | c’ | −0.321 | (−0.580, −0.063) |

| Model 4 | |||

| Total effect Informal trust → self-rated health | c (indirect + direct) | 0.004 | (−0.277, 0.284) |

| Informal trust → depression | A | 0.068 | (−0.091, 0.227) |

| Depression → self-rated health | B | −0.405 | (−0.641, −0.196) |

| Indirect effect | a * b | −0.028 | (−0.104, 0.041) |

| Direct effect | c’ | 0.031 | (−0.242, 0.305) |

| Model 5 | |||

| Total effect Informal trust → self-rated health | c (indirect + direct) | 0.004 | (−0.277, 0.284) |

| Informal trust → anxiety | A | −0.025 | (−0.153, 0.104) |

| Anxiety → self-rated health | B | −0.471 | (−0.730, −0.212) |

| Indirect effect | a * b | 0.012 | (−0.052, 0.083) |

| Direct effect | c’ | −0.008 | (−0.282, 0.267) |

| Model 6 | |||

| Total effect Informal trust → self-rated health | c (indirect + direct) | 0.004 | (−0.277, 0.284) |

| Informal trust → stress | A | −0.026 | (−0.232, 0.180) |

| Stress → self-rated health | B | −0.161 | (−0.326, 0.003) |

| Indirect effect | a * b | 0.004 | (−0.036, 0.046) |

| Direct effect | c’ | 0.000 | (−0.280. 0.279) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Catindig, J.; Atkinson, J.; Llamas, A.; Fernandez-Esquer, M.E. Influence of Trust in Information Sources on Self-Rated Health Among Latino Day Laborers During the COVID-19 Pandemic. COVID 2026, 6, 2. https://doi.org/10.3390/covid6010002

Catindig J, Atkinson J, Llamas A, Fernandez-Esquer ME. Influence of Trust in Information Sources on Self-Rated Health Among Latino Day Laborers During the COVID-19 Pandemic. COVID. 2026; 6(1):2. https://doi.org/10.3390/covid6010002

Chicago/Turabian StyleCatindig, Jan, John Atkinson, Ana Llamas, and Maria Eugenia Fernandez-Esquer. 2026. "Influence of Trust in Information Sources on Self-Rated Health Among Latino Day Laborers During the COVID-19 Pandemic" COVID 6, no. 1: 2. https://doi.org/10.3390/covid6010002

APA StyleCatindig, J., Atkinson, J., Llamas, A., & Fernandez-Esquer, M. E. (2026). Influence of Trust in Information Sources on Self-Rated Health Among Latino Day Laborers During the COVID-19 Pandemic. COVID, 6(1), 2. https://doi.org/10.3390/covid6010002