1. Introduction

The COVID-19 pandemic has posed unprecedented challenges to mental health worldwide, leading to a substantial rise in related issues across the globe [

1]. Data comparing the pre-pandemic period to 2020 shows a notable surge in depression prevalence across 15 major OECD (Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development) countries, with most experiencing more than a twofold increase. South Korea emerged with the highest recorded level of depression at 36.8% and was thus the leading nation [

2].

Women’s mental health has emerged as a critical concern during the pandemic, with studies showing they are disproportionately affected compared to men [

1,

3]. Investigations in countries including the US, Canada, the UK, Italy, China, and Chile have reported more pronounced adverse effects on women’s mental health, which emphasizes a rise in depression, anxiety, and distress rates [

3,

4,

5,

6,

7,

8]. In South Korea, the research on gender differences in mental health during COVID-19 has yielded varied results. Earlier studies that investigated mental health shortly after the outbreak (beyond day 55) found no significant gender differences [

9], but subsequent analyses have revealed disparities between men and women, especially in certain age groups [

10,

11].

Two key factors often cited as contributors to the gender gap in mental health during COVID-19 are employment disruptions and childcare burdens. First, the pandemic has severely affected women’s participation in the labor market, which led to deteriorated mental health outcomes for females [

4,

10]. In contrast to earlier economic recessions, which primarily impacted male-dominated industries such as manufacturing, the COVID-19 crisis disproportionately struck women’s employment, especially in the service sector [

12]. Data from South Korea in 2020 show a marked decline in the employment rate of married women compared with married men during the pandemic [

13], which highlights a change in the way economic crises influence gender-specific employment and mental health. Furthermore, the increased burden of childcare, which was intensified by the shutdown of daycare centers and schools, placed a disproportionate strain on women, who typically assume the childcare role, creating a significant source of stress [

4,

10,

14,

15].

Existing research frequently relies on self-reported, cross-sectional surveys, which can be biased by individuals’ subjective interpretations of their mental health symptoms. To address these limitations, our study utilizes observed data from the National Health Insurance Database (NHID) of South Korea, encompassing healthcare utilization and socioeconomic factors such as income level, employment status, and family structure. We focus on the gender-specific mental health impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic, especially targeting a cohort of insurance subscribers with employee health insurance status in 2019, right before the pandemic. Depression was selected as the primary mental health outcome because it is one of the most prevalent and disabling conditions globally and is strongly associated with key pandemic-related stressors such as job loss and increased caregiving burden [

16]. Depression can escalate to severe outcomes such as suicide, making early detection and treatment a priority for public health prevention [

17]. Among various mental health conditions, depression is also more consistently recorded in administrative health data due to its clear diagnostic coding and treatment pathways, allowing for reliable identification in large-scale datasets [

18]. Our retrospective cohort study aims to identify risk factors for newly diagnosed cases of depression in the employed population during the pandemic. Based on the previous literature, we hypothesize that working women, particularly those who lost jobs or have young children, have been more adversely affected [

1,

3,

4,

5,

6,

7,

8,

10,

11,

14,

15]. This research has important policy implications because it supports the development of more effective health and economic interventions for vulnerable populations concerning mental health, which enhances preparedness for future health crises.

2. Background

In South Korea, the COVID-19 pandemic led to one of the longest periods of school closure among major economies. Beginning with the first confirmed case in January 2020, the government implemented a series of partial and full school shutdowns aimed at preventing in-school transmission. The start of the spring semester in 2020 was delayed multiple times, and even after resumption, in-person classes remained restricted until the first half of 2022. According to UNESCO (United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization), South Korea experienced a total of 76 weeks of partial or full school closures from March 2020 to October 2021—surpassing durations observed in the United States (71 weeks), Germany (38), the United Kingdom (27), China (27), and Japan (11) [

19].

These prolonged disruptions to childcare and education services substantially increased the caregiving burden on households, particularly for working mothers. An international survey conducted by the Boston Consulting Group in 2020 across five countries—the US, UK, Germany, Italy, and France—found that parents nearly doubled the weekly hours spent on childcare and domestic work during the pandemic [

20]. Similarly, a study conducted in Ireland found that the surge in homeschooling brought on by school closures was associated with increased negative emotions, highlighting the emotional strain parents—especially mothers—faced during this period [

21]. In Korea, although nationally representative time-use data for this period is unavailable, a 2020 survey of parents with children under the age of nine showed that 69.7% of mothers experienced increased stress related to caregiving, compared to 54.1% of fathers. This suggests a heightened caregiving burden disproportionately affecting women [

22].

The economic consequences of the pandemic further widened existing gender inequalities. According to an analysis by the Bank of Korea, women were more likely to experience employment disruptions than men—particularly those with young children. Korean women were also more likely to work in face-to-face service sectors, limiting their ability to work remotely. Additionally, they were more frequently employed in temporary or daily-wage positions, with 21.7% of women in such jobs compared to 10.3% of men, making them more susceptible to job loss and economic insecurity [

23].

These structural vulnerabilities translated into mental health challenges. A national survey conducted by the Ministry of Health and Welfare in 2022 found that individuals who experienced income loss during the pandemic were nearly twice as likely to be at risk of depression (22.1%) compared to those whose income remained stable (11.5%) [

24]. When combined with increased caregiving responsibilities and limited employment flexibility, these factors may have exacerbated mental health burdens, particularly for working mothers.

3. Material and Methods

3.1. Data and Study Population

The National Health Information Database (NHID), developed and maintained by the National Health Insurance Service (NHIS), is a nationwide administrative health dataset that includes medical claims data, insurance eligibility, and demographic information for approximately 98% of the Korean population [

25]. As enrollment in the NHIS is mandatory for all residents of South Korea, the NHID serves as the most comprehensive and representative national data source for analyzing healthcare utilization and socio-demographic factors. The database is constructed from healthcare provider claims submitted for reimbursement, allowing for detailed tracking of medical diagnoses, procedures, prescriptions, and service utilization. Its use of administrative health data enables objective measurement of clinical outcomes and minimizes the recall bias common in self-reported surveys [

25].

South Korea operates a national health insurance system for all citizens, which categorizes enrollees into two main types: employee insureds (71.3%) and self-employed insureds (25.8%) as of 2022. This distinction is critical as employee insureds often have stable employment and regular income, which may influence their healthcare access and mental health outcomes, whereas self-employed insureds may face greater economic instability, impacting their inclusion and analysis in the study. The remaining 2.9% of the population are beneficiaries of medical aid, and they receive government support to access medical services without financial burden. A retrospective analysis of a cohort of the population was performed using customized data from the NHID spanning from 2002 to 2022.

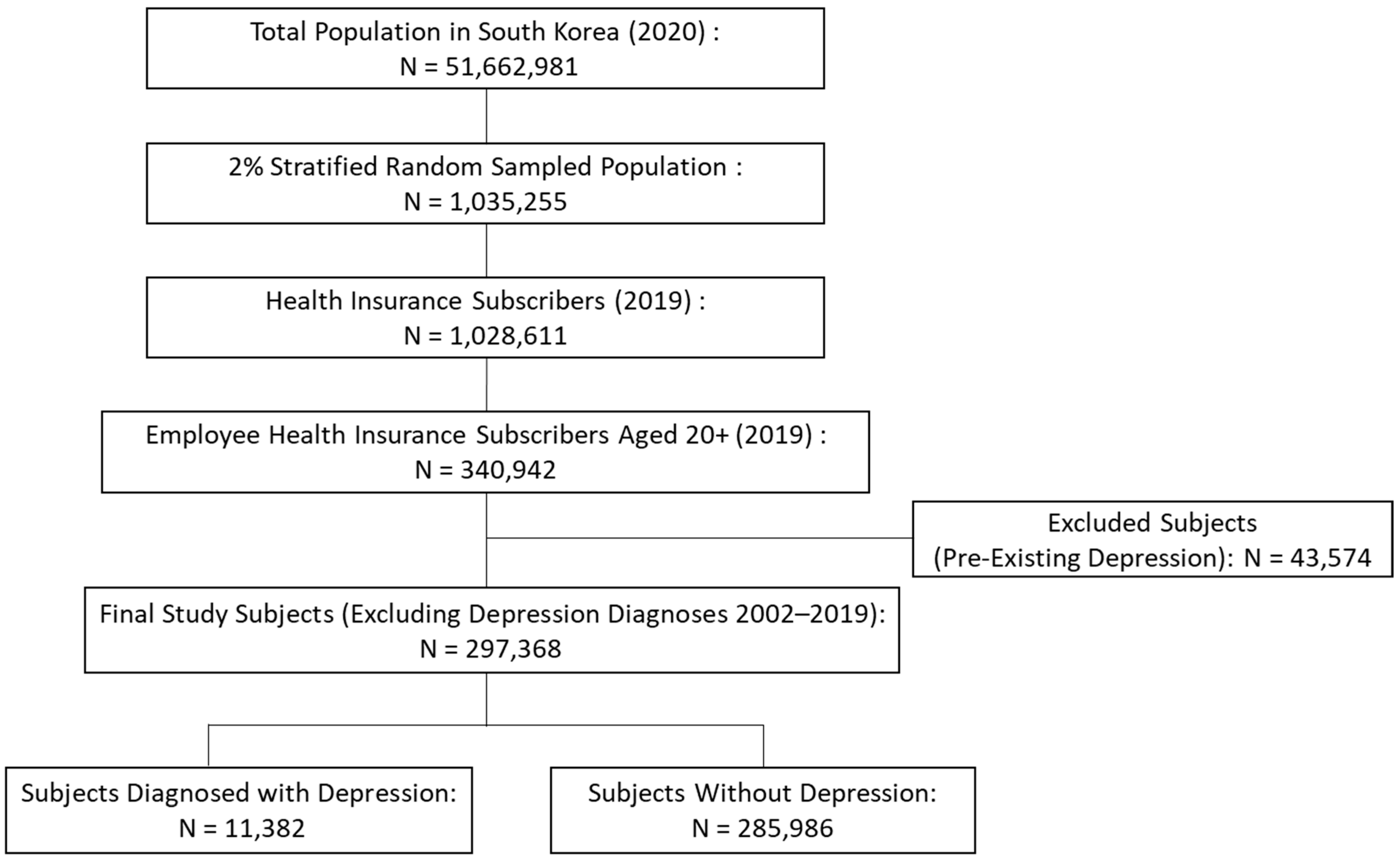

Our study population was restricted to individuals aged over 20 years during the period of 2019–2020. This age restriction was applied because individuals under 20 years are less likely to have stable employment or significant childcare responsibilities, which are central to the study’s objectives. We used 1,035,255 individuals (2% stratified random sample from the total Korean population), who were selected through stratified sampling by age, sex, and residence from a total population of 51,662,981 in 2020. Among them, consecutive observations between 2019 and 2020 were made, with a focus on 340,942 participants who were employees in 2019. We excluded 43,574 subjects with depression in the period of 2002–2019 to eliminate potential confounding factors, ensuring the validity of the analysis by focusing only on new cases of depression, diagnosed during the study period. The final study subjects were 297,368. Then, we confirmed that, among the study population, 285,986 subjects remained without depression, while 11,382 were newly diagnosed with depression during the COVID-19 pandemic period (2020–2022). Regarding follow-up outcomes, the COVID-period mortality rate among the sample ranged from 0.11% to 0.16%, with 314 individuals dying in 2020, 385 in 2021, and 482 in 2022. This breakdown establishes the baseline for analyzing the pandemic’s mental health impact.

Figure 1 presents the flowchart of the study.

3.2. Dependent Variable

This study examined the impact of the pandemic on mental health, with the primary outcome variable being individuals’ mental health. Outpatient medical visits with depression as the principal diagnosis, used as a representative indicator, were specifically focused on. The relevant disease codes, based on the Korean Standard Classification of Diseases (KCD-8), include F32 (depressive episode), F33 (recurrent depressive disorder), F34 (persistent mood [affective] disorders), F38.1 (other recurrent mood [affective] disorders), F40 (phobic anxiety disorders), F41 (other anxiety disorders), F42 (obsessive–compulsive disorder), and F43 (reaction to severe stress and adjustment disorders) [

26]. These codes represent a range of mental health conditions commonly associated with depression, anxiety, and stress-related disorders. Similar diagnostic codes have been employed in previous studies using administrative data to assess mental health outcomes [

18,

27]. Building on this approach, the present study included a broader set of related codes to more comprehensively examine the mental health impacts of pandemic-related stressors. By focusing on outpatient visits with these specific diagnoses, we aim to assess the impact of the pandemic on individuals’ mental well-being. Depression occurring before the index date was excluded, so depression was defined as depression occurring after this date.

3.3. Independent Variables

This study used gender, age, income level, marital status, employment status, and child age as independent variables to investigate the impacts of unprecedented health crises like COVID-19 on mental health. We focused on the two economic stressors—job loss and childcare burden—as key variables to explain the gender disparity in mental health outcomes in the pandemic era.

The impact of COVID-19 on employment was most severe in the service sectors, which predominantly encompass female-friendly jobs. This sector’s heterogeneity implies disproportionate strain on females, including intensified job-seeking challenges and heightened financial burdens beyond the job loss itself.

The operation of childcare and educational institutions was temporarily halted as part of social-distancing measures to minimize infections in communal facilities. Unexpected childcare hours increased due to the operational restrictions of childcare and educational institutions. Some individuals faced the dilemma of choosing between childcare and occupational activities, except for workers who could flexibly adjust labor supply through telecommuting or flexible work arrangements. South Korea experienced notably prolonged school closures compared to many other countries, significantly amplifying caregiving responsibilities for households with young children, particularly those in early elementary grades. It also has one of the widest gender gaps in household labor among developed countries, which is especially pronounced in caregiving roles. These contextual factors provide a favorable setting to analyze how pandemic-related intensification of childcare responsibilities disproportionately impacted women’s mental health.

Job loss experiences were measured using the following operational definition: if an individual had formal employment status in 2019 but experienced a change in status in 2020, specifically transitioning to being a dependent of a “wage earner” (employee insureds), a “regional subscriber” (self-employed insureds), or a medical aid beneficiary, then they were defined as having experienced job loss. This study examined child age and marital status to measure childcare burdens. Child age was divided into under 18 and 7–9 years, considering that younger ages require more parental care. The childcare burden measures only considered whether an individual had any child in the age groups of interest rather than the number of children. It is also notable that the categorization is not exclusive; that is, an individual who has children aged 7~9 also falls into the group having children aged under 18. Income level was represented by health insurance premiums and was categorized into five quintiles to examine income-level differences.

3.4. Statistical Analysis

We analyzed the factors affecting mental health through an examination of the healthcare utilization patterns of citizens in response to the external shock of the pandemic. First, we determined the frequency distribution of socio-demographic characteristics for our sample. Second, multivariable Cox proportional hazard regression analyses were performed to estimate the hazard ratios (HRs) and 95% confidence intervals [

28]. Multivariable models were adopted to assess the association between socio-demographic factors and the incidence of depression so that the HR of each risk factor could be calculated. We assessed the proportional hazards assumption using Schoenfeld residuals, and the residual plots showed consistent time patterns across all covariates, supporting the validity of the assumption. Subgroup analyses were conducted to evaluate differences by sex. In addition, we conducted a multivariable analysis in the labor market active age group of 20–49. All statistical analyses were performed using the SAS version 9.4 software (SAS Institute Inc, Cary, NC, USA).

4. Results

Table 1 presents the socio-demographic characteristics of 297,368 adults, comprising 178,350 men (60%) and 119,018 women (40%). Among women, 20.2% were aged 20–29 compared to 12.5% of men. Men dominated the 30–69 age groups, while women accounted for 1.3% in the ≥70 group compared to 2.4% of men.

Income disparities were evident, with women being more concentrated in the lowest income quartiles (1st: 34.3%; 2nd: 30.9%) compared to men (1st: 16.0%; 2nd: 20.3%). Marital status data showed that 63.9% of participants were married.

Women experienced job loss more frequently (20.8%) than men (17.2%), reflecting greater employment instability during the pandemic. A substantial proportion of both men and women had children. Specifically, 35.6% of men and 32.1% of women had at least one child under the age of 18. Additionally, 9.1% of men and 7.0% of women had a child aged 7–9, indicating that a notable share of the sample faced childcare responsibilities during the pandemic, including challenges related to homeschooling during school closures.

The incidence of newly diagnosed depression during the pandemic was slightly higher among women (3.3%) than men (3.1%), suggesting that the pandemic’s mental health impact was more significant for women.

Table 2 presents findings from multivariate survival regression analyses aimed at identifying depression risk factors in the total sample. It specifically examines the impact of job loss in Column 1, and family structure, especially childcare burden, in Column 2. Column 3 integrates job loss and childcare burden effects. Individuals who experienced job loss during the pandemic demonstrated a significantly higher likelihood of depression, with a Hazard Ratio (HR) of 1.18 (95% CI: 1.13 to 1.24). These results highlight the mental health vulnerabilities associated with employment instability during the pandemic.

Additionally, having a child in lower elementary grades was linked to an increased rate of depression, with an HR of 1.13 (95% CI: 1.05 to 1.22). This finding suggests that managing school-aged children during the pandemic may have contributed to heightened psychological distress among employed parents. The analysis further revealed a U-shaped relationship between age and depression, with individuals in their 40s exhibiting the lowest depression rates. Younger and older age groups were more vulnerable, reflecting age-specific susceptibilities to mental health challenges.

Individuals in the highest income quartiles exhibited slightly higher rates of depression. This trend may be linked to workplace pressures, the psychological strain of high-responsibility roles, or increased access to mental health diagnoses and treatment in higher-income populations. Overall, the findings emphasize the compounded risks faced by women, younger individuals, and those managing both job loss and childcare burdens during the COVID-19 pandemic.

The subgroup analyses in

Table 3 provide further insights into gender disparities in depression risk. Job loss was associated with an increased risk of depression for both men and women, with women showing a slightly higher hazard ratio (HR: 1.22; 95% CI: 1.14 to 1.29) compared to men (HR: 1.15; 95% CI: 1.07 to 1.23). This gender-specific vulnerability may be attributed to heightened job search stress and anxiety over financial exhaustion, particularly as female-dominated occupations, such as those in the service sector, were disproportionately affected by the pandemic shock [

13]. The analysis also highlights the U-shaped relationship between age and depression risk for both genders, with younger and older individuals exhibiting higher risks compared to those in their 40s. Additionally, income disparities were evident, with women in higher income brackets demonstrating elevated depression risks compared to their male counterparts. These results highlight the compounded vulnerabilities faced by women managing job loss, childcare burdens, and pandemic-related stress, emphasizing the urgent need for gender-sensitive interventions to address these disparities.

Figure 2 focuses on the age subgroup of 20 to 40 years who are actively involved in the labor market and childcare. While the overall results align with previous findings, gender differences become more apparent in this group. Women who experienced job loss had a higher likelihood of depression (HR: 1.25; 95% CI: 1.16 to 1.34) compared to men (HR: 1.19; 95% CI: 1.10 to 1.30). Marriage was associated with a lower risk of depression for women (HR: 0.82; 95% CI: 0.75 to 0.88), whereas no protective effect was observed for men (HR: 1.05; 95% CI: 0.96 to 1.14). This suggests that while marriage may offer emotional and social support for women, it does not appear to provide the same mental health benefits for men and may even be associated with increased stress. Having children under 18 was associated with a protective effect against depression for both genders (HR: 0.87; 95% CI: 0.80 to 0.95 for women; HR: 0.87; 95% CI: 0.79 to 0.95 for men). However, having a child aged 7–9 in 2019 was associated with an increased risk of depression for both genders, but the effect was more pronounced for women (HR: 1.15; 95% CI: 1.02 to 1.30) than for men (HR: 1.11; 95% CI: 1.00 to 1.22). These findings indicate that while both parents faced increased stress, mothers bore a disproportionate mental health burden due to their heightened caregiving responsibilities during the pandemic.

5. Discussion

This study analyzed the gender-specific mental health impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic, using data from the NHID to identify risk factors for newly diagnosed depression cases. By focusing on a large cohort of employed individuals, the findings provide insights into how economic instability, caregiving burdens, and income disparities influenced mental health outcomes during the pandemic.

The results indicate that women had a higher risk of depression than men, with an estimated 63–65% increase in likelihood. This aligns with previous research highlighting gender disparities in mental health outcomes during crises [

5,

7,

10]. Economic stressors, particularly job loss, had a substantial impact, with women who lost their jobs showing a 22% higher likelihood of depression, compared to 15% for men. The gender disparity was more pronounced among individuals aged 20–49, where women’s risk was 25% while men’s was 19%. This pattern reflects structural labor market inequalities and the vulnerability of female workers in pandemic-sensitive industries, such as the service sector.

Family structure also influenced mental health outcomes, but its effects varied by gender and age. Marriage was associated with a reduced risk of depression among women aged 20–49, with an estimated 18% lower likelihood, suggesting that social support from a partner may have played a role in buffering pandemic-related stress for this subgroup, which is consistent with prior research showing the buffering effects of partnerships on mental health [

3,

11,

29]. However, no significant protective effect was observed for men, indicating that marital status alone may not be a universal factor in mitigating depression risk.

Parental responsibilities had mixed effects on mental health. The presence of children under 18 was generally associated with lower depression rates, possibly due to emotional support from family life. However, having younger children, particularly those in lower elementary grades, was linked to an increased risk of depression. This suggests that while parenthood may offer emotional benefits, the added caregiving responsibilities of young children during the pandemic created significant stress for many parents.

The observed gender disparities in mental health outcomes during the pandemic presumably stem from entrenched social norms and labor market structures that disproportionately allocate caregiving responsibilities to women. Cultural expectations and gender roles often position women as primary caregivers, significantly increasing their stress and workload, particularly during periods of crisis when caregiving demands surge. These findings align with the Gender Role Strain Paradigm [

30], which suggests that socially prescribed gender roles can generate psychological strain when individuals are unable or unwilling to meet those expectations. In addition, the patterns observed in this study reflect the principles of Work–Family Conflict Theory [

31], which posits that competing demands from work and family roles can result in psychological distress, particularly when institutional or social support is lacking.

Income level, measured through health insurance premium quartiles, was significantly correlated with depression risk. Individuals in the highest income quartiles exhibited increased depression rates, a trend also observed in previous studies. This may reflect multiple factors, including financial uncertainty among asset-holders and business owners, as well as higher healthcare utilization among high-income individuals, leading to more frequent depression diagnoses [

32]. Gender differences were notable, with high-income women being 41% more likely to experience depression compared to those in the lowest income quartile, while high-income men had only a 15% increased likelihood. These findings suggest that high-earning women may face greater pressures related to work–life balance, caregiving responsibilities, and professional expectations, contributing to their heightened vulnerability to depression.

A U-shaped relationship between age and depression was observed, with the lowest depression rates among individuals in their 50s. This may reflect greater life stability, accumulated coping resources, and relatively stable employment during midlife. In contrast, younger and older individuals exhibited higher depression risks, which may be due to economic instability, career uncertainty, or declining health [

33].

These findings underscore the urgent need for gender-sensitive policy responses to pandemic-induced mental health inequalities. International research has consistently emphasized that women disproportionately bore the burden of unpaid caregiving during COVID-19, contributing to psychological distress and labor market detachment [

15,

34]. To address these disparities, governments should prioritize expanding affordable childcare services and increasing public investment in care infrastructure [

35].

Moreover, flexible work arrangements—such as telecommuting and adjustable work hours—have been identified as protective factors that mitigate mental health deterioration among working women [

36,

37]. Policymakers should encourage employers’ adoption of these practices beyond the pandemic. Finally, targeted mental health interventions, including subsidized psychological services for high-risk groups (e.g., single mothers and high-income professionals facing burnout), are essential to build long-term resilience.

6. Conclusions

This Korea-based study provides empirical evidence on the gender-specific impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic on mental health among employed individuals. Women had a higher risk of depression than men, especially among those who experienced job loss, had young children, or belonged to high-income professional groups. These results align with findings from other countries, including the UK and the US, which also reported intensified gender inequalities in mental health during the pandemic [

15,

34,

38].

The study highlights how the intersection of employment instability and caregiving responsibilities—particularly for school-aged or younger children—exacerbated psychological distress among women. This reflects international evidence that women are disproportionately burdened with unpaid care work, leading to role conflict, time poverty, and adverse mental health outcomes [

15,

34,

39]. Interestingly, high-income women exhibited a 41% higher risk of depression than their lower-income counterparts, suggesting heightened pressure from work–life imbalance and professional expectations—echoing concerns in both high- and low-income countries regarding gendered responsibilities and insufficient caregiving infrastructure [

40].

A notable strength of this study lies in its use of objective, clinically diagnosed mental health outcomes, rather than self-reported survey data. This enhances the validity of its findings and distinguishes it from many prior studies relying on subjective measures of psychological distress [

34,

38].

Nevertheless, the study has several limitations. First, due to the inherent nature of administrative health data, the analysis lacked important explanatory variables such as telecommuting practices, household division of caregiving labor, or access to mental health services—all of which are known to mediate pandemic-related mental health outcomes [

15,

34]. In addition, the dataset does not include information to distinguish between voluntary and involuntary job loss, which limits interpretation of the employment-related mental health effects. Second, the use of health insurance premiums as a proxy for income may not fully capture household economic vulnerability, a limitation often cited in administrative labor studies [

40]. Third, the analysis focused exclusively on depression and did not include other critical dimensions of mental health, such as anxiety, burnout, or stress, thereby narrowing the scope of interpretation [

39]. Fourth, our definition of depression, which only counts individuals utilizing healthcare services, could introduce detection bias. Finally, the cross-sectional design limits causal inference, as it does not track mental health trajectories before and after the pandemic, unlike panel or repeated-measures studies that can capture psychological change over time [

38]. In addition, as this study is based solely on South Korean data and institutional context, the generalizability of the findings to other countries with different labor market structures, cultural norms, and public health systems may be limited. Comparative studies across diverse national settings are needed to validate the broader applicability of these results.

Despite these limitations, this Korea-based study makes an important empirical contribution to understanding pandemic-induced mental health inequalities. The findings offer evidence to inform gender-sensitive and equity-oriented public health responses.