Abstract

The COVID-19 pandemic significantly impacted daily life, disrupting routines and altering lifestyle behaviors. This study aimed to investigate changes in body weight, nutritional status, and weight loss practices among adults in Türkiye during the first year of the pandemic. A cross-sectional online survey was conducted between March and April 2021, including 806 participants. Height and weight were self-reported, and weight loss practices, along with their details, were evaluated. A qualitative component explored participants’ perceptions of weight change, with 274 valid responses. The mean weight gain during the pandemic was 0.88 kg (p < 0.001). Among participants, 44.9% reported weight gain, 22.6% reported weight loss, and 14.1% experienced weight fluctuation. Among those who experienced weight fluctuations, 47.4% resulted in weight loss, 14.9% showed no change, and 37.7% experienced weight gain. The prevalence of overweight increased from 19.2% to 22.8%, and obesity rose from 8.7% to 9.4% (p = 0.005). Regarding weight loss practices, 30.1% of participants engaged in physical exercise, while 25.7% reported following weight loss diets. Qualitative analysis revealed that changes in physical activity, eating habits, and psychological factors were key determinants of weight change. These findings emphasize the diverse effects of the pandemic on weight status and management.

1. Introduction

The coronavirus disease (COVID-19), caused by the SARS-CoV-2 virus, first emerged in Wuhan, China, in December 2019. Following its rapid global spread, the World Health Organization (WHO) declared COVID-19 a pandemic on 11 March 2020 [1]. On the same date, the first COVID-19 case was reported in Türkiye. In response, the Turkish government announced the first restrictions on March 16, including the closure of public venues such as restaurants, gyms, and cultural spaces. Over time, broader measures were implemented, including lockdowns, curfews, school closures, and limitations on travel and working hours [2]. Yet despite these measures, official statistics reported 22,136 COVID-19-related deaths in Türkiye in 2020, rising sharply to 65,198 in 2021 [3].

While infections and deaths were the most immediate and prioritized outcomes of the COVID-19 pandemic, a range of additional effects also emerged at both individual and population levels. The preventive measures implemented to limit the spread of the virus led to significant social and economic burdens, changes in population behavior, and various health-related consequences [4,5]. One of the health-related consequences was the impact on nutritional status, which was significantly affected through various direct and indirect mechanisms. Food systems experienced substantial strain due to interruptions in agricultural production, labor shortages, logistical challenges, and shifts in consumption patterns, all of which disrupted the continuity and resilience of food supply processes [6]. Reduced food availability and access were among the most immediate effects reported, alongside rising prices of staple foods such as cereals and legumes. These challenges led to decreased dietary diversity, lower diet quality, and changes in eating habits in many regions [7]. Restrictions such as lockdowns and mobility limitations led to major changes in food purchasing and consumption behaviors, including reduced frequency of food shopping, increased preference for long shelf-life products, decreased access to fresh foods, and a shift from in-person to online food purchases [8]. In addition to structural and behavioral changes in food systems, pandemic-related psychological distress was also linked to increased emotional eating, higher snacking frequency, and disrupted self-regulation in dietary behavior [9,10]. These behavioral disruptions have been associated with significant changes in body weight during the pandemic period. Longitudinal studies indicate that both children and adults experienced a modest yet significant increase in body weight and obesity rates during the first year of the pandemic [11]. However, the nutritional impact of COVID-19 restrictions was not unidirectional; both weight gain and weight loss have been reported, suggesting highly variable individual responses [12]. These variations in weight change status are often attributed to differences in personal coping strategies and behavioral adaptations to pandemic-related stressors [13].

In addition to food-related and psychosocial factors associated with body weight changes, the pandemic also caused significant reductions in overall physical activity levels and increases in sedentary behaviors across all age groups. These changes were primarily attributed to limited mobility, closure of recreational spaces, and reduced access to safe community environments that support active living. Although some populations reported increased use of parks or engagement in leisure-time activities, the general trend highlighted a substantial decline in walking, moderate-to-vigorous physical activity, and daily energy expenditure [14]. Reduced physical activity was identified among the primary contributors to pandemic-related weight changes, and combined with altered dietary patterns, these lifestyle changes posed a risk of persisting beyond the pandemic period [15]. Given that obesity was already a major public health concern prior to the pandemic, understanding its dynamic evolution in this context is critical. According to the Türkiye Nutrition and Health Study published in 2019 [16], 34% of adults were classified as overweight and 27.8% as obese, whereas only 1.7% were underweight. Although this dataset has not yet been updated, findings from the Turkish Statistical Institute indicate that overweight prevalence slightly increased from 30.4% in 2019 to 30.9% in 2022, while obesity rates slightly decreased from 24.8% to 23.6% [17]. These contrasting trends suggest that weight trajectories during and after the pandemic may have followed divergent paths across population subgroups, reflecting a complex interplay of behavioral, contextual, and psychosocial factors.

In light of these widespread lifestyle changes and heterogeneous outcomes, the present study aimed to evaluate self-reported changes in body weight and nutritional status over a one-year period among adults in Türkiye. To capture the complexity of individual experiences, a distinct “weight fluctuation” category was included alongside weight gain and loss. Moreover, a qualitative component was incorporated to better understand participants’ subjective explanations for weight changes, providing contextual depth to the quantitative findings.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Sampling

This study was designed as a cross-sectional survey and conducted online between 22 March and 17 April 2021, approximately one year after the first confirmed case of COVID-19 was reported in Türkiye on 11 March 2020. Data were collected using a structured questionnaire prepared with Google Forms. This study used a convenience sampling approach, with participants initially recruited through social media, messaging applications, and email groups. To enhance the sample size, a snowball sampling technique was also applied by encouraging participants to share the survey link with others.

Sample size estimation was based on the primary analysis comparing pre-pandemic and current body weight using a paired samples t-test. A priori power analysis was conducted using G*Power 3.1.9.7 [18]. The parameters included a small effect size (Cohen’s dz = 0.2), an alpha level of 0.001 to control for type I error, and a statistical power of 0.95. The analysis indicated that a minimum of 615 participants would be required to detect significant weight change between two time points. The inclusion criteria were being between 18 and 65 years of age, residing in Türkiye, and providing voluntary informed consent to participate. The exclusion criteria were being pregnant, currently breastfeeding, or following a special dietary model that significantly influenced usual food or food group consumption for personal or medical reasons. These criteria were verified through screening questions within the questionnaire. A total of 883 responses were initially collected. After excluding 9 individuals who did not meet the eligibility criteria, 5 who did not provide consent, 2 whose responses were inconsistent or not logically interpretable, and 61 duplicate entries, the final sample consisted of 806 participants.

2.2. Measures

2.2.1. Demographic Information

Participants were asked to report a range of demographic characteristics, including sex, age, marital status, education level, income status, occupation, and tobacco use. Age and city of residence were collected as open-ended responses. For reporting purposes, age was later categorized into three groups as follows: 18 to 24 years, 25 to 44 years, and 45 to 65 years. Response categories for marital status, education level, income, occupation, and tobacco use aligned with those reported in the descriptive analysis.

2.2.2. Self-Reported Body Weight Change

Participants were asked to report changes in their body weight during the one-year period of the COVID-19 pandemic. Response options included increased, no change, decreased, gained weight after losing, and lost weight after gaining. The last two categories were combined under the label “weight fluctuation” to improve clarity. Participants were asked to report their height and body weight, specifying their weight both before the pandemic and at the time of the survey. These values were provided as open-ended responses. Body mass index (BMI) was calculated for each participant using height and weight values and was classified into four categories: underweight, normal weight, overweight, and obese. The cut-off values used for classification were as follows: underweight (<18.5 kg/m2), normal (18.5–24.9 kg/m2), overweight (25.0–29.9 kg/m2), and obese (≥30.0 kg/m2) [19]. Changes in body weight and nutritional status were determined by comparing self-reported values before the pandemic and at the time of the survey.

2.2.3. Qualitative Setting

To gain a deeper understanding of the reasons behind body weight changes, a qualitative component was included in the study. Participants were asked to respond to the following non-obligatory open-ended question: “If your body weight changed during the COVID-19 pandemic, what do you associate this change with? Please explain”. A total of 336 participants out of the 806 survey respondents answered this question. After excluding 47 participants who did not provide any explanation, 9 who explicitly stated that the change was unrelated to the pandemic, and 6 who had reported no body weight change in a previous survey item, 274 valid responses were included in the qualitative analysis.

2.2.4. Weight Loss Practices

Weight loss practices were assessed using a multiple-choice question with the following options: following a diet, engaging in exercise, using weight loss products, other methods, or none of the above. Participants who reported following a weight loss diet were directed to an additional section. This section gathered information on the types of diets they used, their sources of diet information, whether they successfully lost weight, and whether they had attempted the diet before the pandemic. The list of diet types included in the survey was developed based on commonly reported practices identified in previous studies [20,21] and supported by an internet search of popular diet trends.

2.3. Statistical Analysis

Quantitative analyses were conducted using IBM SPSS Statistics, version 21.0. The distribution of body weight change was assessed using visual (histograms and probability plots) and analytical (Kolmogorov–Smirnov and Shapiro–Wilk) methods. As the data were normally distributed, paired Student’s t-test was used to compare pre-pandemic and current body weight within weight change. Nutritional status changes were expressed as percentages, and the McNemar–Bowker test was applied to assess the significance of shifts between categories. Pearson’s chi-square test was used for comparisons between categorical groups, with p-values less than 0.05 considered statistically significant [22].

For the qualitative analysis, open-ended responses were extracted directly from Google Forms and transcribed. The data were interpreted using an inductive thematic analysis approach, allowing themes to emerge organically from the participants’ narratives [23]. Two researchers independently coded the responses, then compared and discussed their codes to reach consensus under the supervision of the study coordinator. Final codes were organized into categories and then clustered into overarching themes. Thematic analysis was conducted separately for each weight change group.

3. Results

3.1. Participants

Table 1 presents the main characteristics of the study participants. The mean age of participants was 29.6 years, with a standard deviation of 10.7 years and ranging from 18 to 65 years. The sample largely consisted of females (76.9%, n = 620) and individuals aged between 18 and 24 years (47.1%, n = 380). Most respondents were single (61.7%, n = 497), students (39.5%, n = 318), and never smokers (65.8%, n = 530). Regarding education level, the majority had a university degree (81.8%, n = 659). In terms of income status, half of the participants reported that their income was equal to their expenses (50.6%, n = 408).

Table 1.

Characteristics of the study population.

3.2. Self-Reported Body Weight Change During the COVID-19 Pandemic

Table 2 summarizes participants’ self-reported body weight changes, along with their pre-COVID-19 and current body weights. On average, participants’ body weight significantly increased by 0.88 kg during the one-year COVID-19 pandemic period (p < 0.001). Among all respondents, 14.1% reported weight fluctuation. Of these, 47.4% (n = 54) reported outcomes as weight loss, 14.9% (n = 17) reported no change, and 37.7% (n = 43) reported outcomes as weight gain. In addition, 44.9% (n = 362) of participants reported weight gain without fluctuation, indicating that more than half of the study population experienced weight gain. Only about one-fifth of participants (18.4% with no weight change and 2.1% with weight fluctuation resulting in no change) were able to maintain their pre-pandemic body weight.

Table 2.

Self-reported body weight change during the pandemic.

Self-reported body weight change categories by sociodemographic characteristics is presented in Table 3. There was a significant association between sex and weight change categories (p = 0.031). Weight gain was the most reported outcome for both males (50.0%) and females (43.1%), but males had a higher proportion. Conversely, females more frequently reported weight loss compared to males (24.7% vs. 15.6%). Age group was also significantly associated with weight change (p = 0.004). Participants aged 45–65 showed the highest weight gain (50.5%), while those aged 18–24 had the highest weight loss (27.6%). Marital status was significantly associated with weight change (p < 0.001). Weight gain was more common among married participants (54.7%) than singles (39.1%), while weight loss was more frequently reported by singles (26.8% vs. 15.0%). Weight gain was most common among employed participants (51.9%), while weight loss was more frequently reported by students (30.2%) (p < 0.001). No significant associations were found for education level (p = 0.075), income status (p = 0.732), or tobacco use (p = 0.091).

Table 3.

Self-reported body weight change categories by sociodemographic characteristics.

3.3. Pandemic-Related Changes in Participants Causing Body Weight Change

A total of 274 participants responded to the open-ended question regarding pandemic-related changes associated with body weight. The responses were analyzed thematically and categorized into 13 subthemes under four main themes. Across the total sample, the most commonly reported factor was changes in physical activity level and sedentary behavior (39.8%), followed by changes in eating quantity and appetite (19.3%). Among participants who reported weight gain, physical inactivity (48.8%) and increased snack or comfort food consumption (11.6%) were frequently mentioned. In contrast, weight loss was most commonly attributed to psychological distress (23.0%) and intentional weight management behaviors (14.8%). For those reporting weight fluctuation, physical activity-related changes (51.2%) and eating quantity/appetite (24.4%) were most cited. Contextual factors such as home confinement (16.4%) and curfew restrictions (4.7%) also emerged as relevant influences across all groups (Table 4).

Table 4.

Reported themes associated with body weight changes by weight change categories.

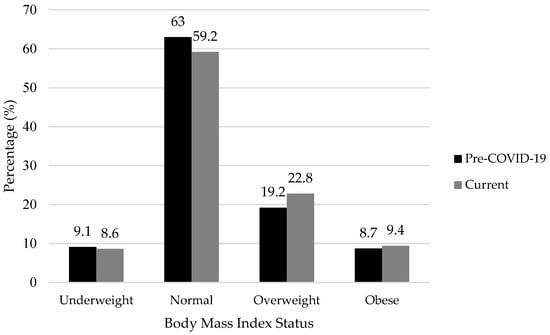

3.4. Self-Reported Nutritional Status Change During the Pandemic

Self-reported height and body weight data were used to calculate participants’ BMI before and during the COVID-19 pandemic. A statistically significant shift in nutritional status distribution was observed (p = 0.005). The proportion of underweight individuals slightly decreased from 9.1% to 8.6% and normal weight from 63.0% to 59.2%. In contrast, the proportion of overweight individuals increased from 19.2% to 22.8%, and obesity prevalence rose from 8.7% to 9.4% (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Changes in nutritional status during the COVID-19 pandemic. Statistical comparisons were performed using the McNemar–Bowker test (p = 0.005).

3.5. Weight Loss Practices During the COVID-19 Pandemic

Weight loss practices during the pandemic varied significantly across BMI categories (Table 5). Overall, 25.7% of participants reported following a weight loss diet, while 30.1% reported engaging in physical exercise to manage their weight. Only 1.5% of participants reported using weight loss products, indicating minimal usage. Following a weight loss diet was reported by 7.2% of participants with underweight, 24.7% of those with normal BMI, 32.6% of those classified as overweight, and 31.6% of those classified as obese (p = 0.002). Similarly, engaging in physical activity for weight loss was reported by 13.0% of the underweight group, 34.0% of the normal BMI group, 29.9% of the overweight group, and 22.4% of the obese group (p < 0.001). However, although 16.0% of participants (n = 129) reported engaging in both diet and exercise for weight loss, there was no statistically significant association between BMI groups (p = 0.109).

Table 5.

Weight loss practices across the current BMI groups during the pandemic.

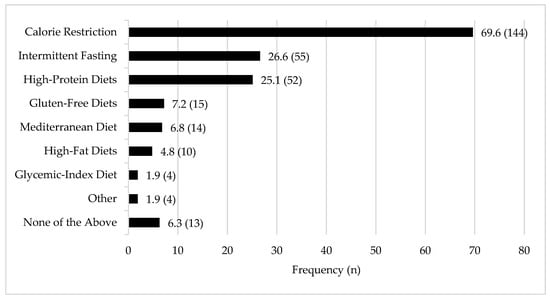

Figure 2 illustrates the types of weight loss diets followed by participants during the COVID-19 pandemic. Participants who reported following a weight loss diet (n = 207) were allowed to select more than one dietary approach. Calorie restriction was the most frequently reported diet (69.6%, n = 144), followed by intermittent fasting (26.6%, n = 55) and high-protein diets (25.1%, n = 52). Less common responses included gluten-free diets (7.2%, n = 15), Mediterranean diet (6.8%, n = 14), high-fat diets (4.8%, n = 10), and glycemic index-based diets (1.9%, n = 4). A small number of participants (6.3%, n = 13) selected either “other” or “none of the above”.

Figure 2.

Frequency of weight loss diet types reported by participants.

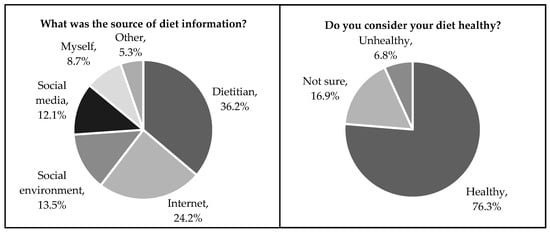

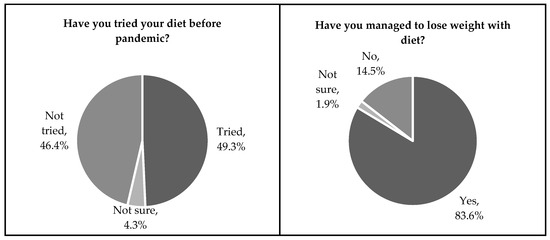

Figure 3 presents participants’ perceptions and experiences related to their weight loss diet practices. Among those who followed a diet during the pandemic, 36.2% reported obtaining dietary information from a dietitian, followed by the internet (24.2%), their social environment (13.5%), and social media (12.1%). Regarding the perceived healthiness of the diets, 76.3% considered their diets healthy, 6.8% unhealthy, and 16.9% were unsure. Nearly half of the respondents (49.3%) had tried the same diet before the pandemic, while 46.4% were trying it for the first time. Notably, 83.6% of the participants reported successful weight loss, whereas 14.5% did not achieve the intended results.

Figure 3.

Diet practice perceptions of the study population.

4. Discussion

This study was planned to compare participants’ weight management practices and weight loss interventions before and during the COVID-19 pandemic, using a mixed-methods approach. This design provided a comprehensive understanding of body weight changes by integrating both quantitative and qualitative data.

Our findings indicated that more than half of the participants reported gaining body weight during the pandemic. This shift was evident in the nutritional status of our participants, with overweight prevalence increasing from 19.2% to 22.8% and obesity rising from 8.7% to 9.4%. Notably, these prevalence rates are lower than the latest national data from the Turkey Nutrition and Health Survey [16], which reported 34.0% for overweight and 31.5% for obesity. This discrepancy suggests that the true population impact of the pandemic on nutritional status in Türkiye may be higher than what our study observed [24]. Furthermore, obesity is recognized as a major public health issue and has been associated with a more severe clinical course of COVID-19 and increased risk of mortality [25,26]. Therefore, implementing effective strategies to prevent weight gain and reduce obesity is of critical importance. This finding of weight gain during the pandemic aligns with a previous systematic review, which reported that weight gain during the pandemic was observed in 7.2% to 72.4% of participants, while weight loss ranged from 11.1% to 32.0% [12]. In our study, 47.4% of participants reported weight loss, while 37.7% experienced weight gain. Additionally, 14.1% of participants experienced weight fluctuations. The COVID-19 pandemic significantly disrupted traditional routines, affecting physical activity, dietary habits, and mental well-being. However, various adaptive strategies, such as engaging in home-based exercises, were also implemented to cope with these disruptions [27]. Similarly, for mental health, evidence indicates an initial increase in distress followed by a recovery to baseline over time in response to the pandemic [28]. The subgroup reporting weight fluctuations (14.1%) may represent individuals who tried multiple adaptive strategies to manage their weight during the pandemic and who eventually recovered from its short-term psychological and behavioral effects.

The pandemic has impacted individuals’ lives variably according to their socio-demographic attributes, leading to alterations in lifestyles and body weights. This study revealed that men, middle-aged individuals, married participants, and those employed saw greater weight increase, whereas women, students, and young adults exhibited higher rates of weight loss. The data demonstrate that socio-demographic variables significantly influence weight change. A systematic analysis comprising 40 papers corroborates these findings [29]. The elevated incidence of weight loss in young people and women can be attributed to heightened nutritional awareness during the pandemic, the impact of social media, and the increased duration of time spent at home [30,31]. The gender component resulted in men and middle-aged persons being more predisposed to weight gain. The adaptation of employees to remote work, reduced physical activity, and altered eating habits as a coping mechanism for work-related stress may have proven successful [30]. Weight increase was more prevalent among married persons, whereas weight decrease was more commonly observed in single individuals; this may be attributed to married individuals partaking in more regular and calorie-dense meals at home [32]. No substantial variations were observed for educational attainment, income level, and smoking status. This may be attributable to the sample predominantly comprising persons with higher educational and economic levels.

Our results indicated that participants who were classified as obese (31.6%) or overweight (32.6%) were more likely to adopt dietary approaches for weight loss, whereas those with a normal BMI (34%) were more inclined to engage in physical exercise. Among the various dietary methods, caloric restriction and intermittent fasting emerged as the most chosen strategies. Evidence in the literature also suggests that higher BMI is significantly associated with dietary restraint and other weight management strategies [33,34]. In line with these findings, our results may indicate that individuals with higher BMI tend to prioritize dietary restraint during extraordinary situations, such as the pandemic. Additionally, an analysis of the themes reported by participants regarding weight gain, loss, or fluctuations during the pandemic revealed that behavioral changes were the most prominent factors. Specifically, the most frequently reported themes included changes in physical activity or sedentary behaviors (49%), reduced exercise opportunities (16%), and variations in food consumption (17%). Taken together, these findings suggest that the pandemic exerted a substantial and multifaceted impact on individuals’ lifestyles, particularly in terms of physical activity and eating behaviors. The primary factors contributing to weight changes were extended time spent at home and restricted physical activity. Similarly, Zachary et al. [32] reported that insufficient physical activity and increased eating frequency were common among individuals who experienced weight gain during the pandemic. Furthermore, psychological stress related to the pandemic has been shown to influence eating behaviors [35,36]. The results also indicate that a substantial proportion of participants who followed weight loss diets obtained dietary information from dietitians (36.2%), while a combined total of 36.3% relied on the internet and social media. This reliance on online platforms is consistent with previous findings, where the COVID-19 pandemic led to a sharp increase in the use of digital health services, followed by a decline over time [37]. However, the widespread use of social media as a dietary information source raises concerns about misinformation and the quality of nutritional guidance available [38]. Given the insufficient regulation on such platforms, individuals may have been exposed to inaccurate or misleading dietary advice. Interestingly, despite the variability in information sources, 76.3% of participants perceived their diets as healthy. However, 14.0% considered their diets unhealthy, which raises important questions about adherence to potentially harmful dietary practices. This highlights a critical issue where individuals prioritize perceived outcomes over nutritional quality.

There are several strengths of our study. The first is that the aspects of society’s weight control behaviors that are different from the routine were investigated in an extraordinary period, namely the COVID-19 pandemic. The use of a mixed method that evaluated both quantitative and qualitative data during this research allowed for an in-depth examination of the findings. The convenience and snowball sampling methods used in this study were important for reaching participants from diverse age groups and socio-economic backgrounds, which enhanced the generalizability of the study findings. Nevertheless, in addition to these, there are specific limitations. We used a self-reported retrospective data questionnaire concerning the time before lockdown, which may be less reliable and biased. However, this was the appropriate approach to use when considering that the pandemic was unpredictable, and it was used in similar studies. Although self-reported retrospective data were appropriate given the unexpected nature of the pandemic, future public health research—particularly in preparation for similar emergencies—should prioritize the inclusion of objective indicators such as clinical or anthropometric measurements, where feasible, to strengthen data validity and policy relevance. The majority of our participants were women, younger-aged, and people with higher education levels, similar to other research. This may be related to the fact that these groups are more willing to participate in the online survey. Since the study was conducted online, individuals without internet access were excluded, limiting the representativeness of the sample. Although it was supported by qualitative research when questioning body weight change and associated with the pandemic, possible confounders other than a pandemic could be effective. In addition, since the qualitative data were collected online via a single open-ended question, the lack of interaction and probing restricted the depth of responses. Consequently, thematic interpretation was limited to surface-level patterns. Future research could explore weight change experiences through in-depth interviews to capture richer narratives, particularly reflecting on past pandemic-related experiences.

In conclusion, using a cross-sectional mixed-methods design, we demonstrated that the COVID-19 pandemic significantly influenced individuals’ perceived weight, largely due to changes in nutritional behaviors and physical activity levels in Türkiye. This was one of the first studies to evaluate both weight gain and weight loss practices in response to an emerging infectious disease context. Notably, participants tended to adopt physical activity rather than diet-focused strategies to manage their weight, reflecting a shift in behavioral patterns during high-stress periods. Future research should further explore the long-term effects of pandemics on nutritional behaviors and weight management, particularly using objective indicators such as anthropometric or clinical measures to enhance data accuracy and reliability. Given that many pandemic-related studies relied on self-reported data, incorporating validated assessment tools will be essential for evaluating impacts on body composition, metabolic health, and related outcomes. Importantly, the findings of this study underscore the need to develop sustainable and equitable public health strategies not only for the COVID-19 pandemic but also for future crises. As observed during the pandemic, certain population groups—particularly women, young adults, and socioeconomically disadvantaged individuals—were disproportionately affected, exacerbating existing health inequalities. Understanding how these vulnerable groups behave and adapt under pressure is critical for designing targeted, inclusive, and context-sensitive health interventions. Public health efforts should therefore adopt a holistic perspective that integrates nutritional, physical, and psychosocial dimensions of well-being. Such an approach would foster preparedness, resilience, and equity in times of public health emergencies.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.H., N.K.-H. and P.B.; methodology, M.H. and N.K.-H.; software, M.H. and N.K.-H.; validation, M.H. and N.K.-H.; formal analysis, M.H.; investigation, M.H. and N.K.-H.; resources, P.B.; data curation, M.H. and N.K.-H.; writing—original draft preparation, M.H. and N.K.-H.; writing—review and editing, M.H., N.K.-H. and P.B.; visualization, M.H., N.K.-H. and P.B.; supervision, P.B.; project administration, P.B.; funding acquisition, P.B. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Ethics Committee of Hacettepe University (Reference number: GO 21/373, Date: 2021/06−41).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study. The survey was administered online via Google Forms, and participation was entirely voluntary and anonymous. Prior to accessing the survey, participants were presented with detailed information regarding the study’s objectives, data usage, participant rights, and researcher contact information. Only those who provided informed consent electronically were granted access to the main questionnaire.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author due to privacy.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| BMI | Body mass index |

| CI | Directory of Open Access Journals |

| COVID-19 | Coronavirus disease 2019 |

| SD | Standard deviation |

| SPSS | Statistical Package for the Social Sciences |

| WHO | World Health Organization |

References

- WHO. Listings of WHO’s Response to COVID-19. 2020. Available online: https://www.who.int/news/item/29-06-2020-covidtimeline (accessed on 8 May 2025).

- The Ministry of Interior of the Republic of Türkiye. Additional Circular on COVID-19 Measures Sent to 81 Provincial Governorships. 2020. Available online: https://www.icisleri.gov.tr/81-il-valiligine-koronavirus-tedbirleri-konulu-ek-genelge-gonderildi (accessed on 8 May 2025).

- Turkish Statistical Institute. Death and Causes of Death Statistics 2021. 2023. Available online: https://data.tuik.gov.tr/Bulten/Index?p=death-and-causes-of-death-statistics-2021-45715&dil=2 (accessed on 8 May 2025).

- Galea, S.; Keyes, K. Understanding the COVID-19 Pandemic through the lens of population health science. Am. J. Epidemiol. 2020, 189, 1232–1237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McBride, E.; Arden, M.A.; Chater, A.; Chilcot, J. The impact of COVID-19 on health behaviour, well-being, and long-term physical health. Br. J. Health Psychol. 2021, 26, 259–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Massoud, L.; Zoghi, M. The effects of the covid-19 pandemic on food systems: Limitations and opportunities. Discover Food 2024, 4, 102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jafri, A.; Mathe, N.; Aglago, E.K.; Konyole, S.O.; Ouedraogo, M.; Audain, K.; Zongo, U.; Laar, A.K.; Johnson, J.; Sanou, D. Food availability, accessibility and dietary practices during the covid-19 pandemic: A multi-country survey. Public Health Nutr. 2021, 24, 1798–1805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dolati, S.; Hariri Far, A.; Mollarasouli, Z.; Imani, A. The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on changes in food choice, purchase, and consumption patterns in the world: A review study. J. Nutr. Food Secur. 2022, 7, 388–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cecchetto, C.; Aiello, M.; Gentili, C.; Ionta, S.; Osimo, S.A. increased emotional eating during COVID-19 associated with lockdown, psychological and contextual factors. Appetite 2021, 160, 105122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marchitelli, S.; Mazza, C.; Lenzi, A.; Ricci, E.; Gnessi, L.; Roma, P. Weight gain in a sample of patients affected by overweight/obesity with and without a psychiatric diagnosis during the COVID-19 lockdown. Nutrients 2020, 12, 3525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anderson, L.N.; Yoshida-Montezuma, Y.; Dewart, N.; Jalil, E.; Khattar, J.; De Rubeis, V.; Carsley, S.; Griffith, L.E.; Mbuagbaw, L. Obesity and weight change during the COVID-19 pandemic in children and adults: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Obes. Rev. 2023, 24, e13550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, M.A.; Menon, P.; Govender, R.; Abu Samra, A.M.; Allaham, K.K.; Nauman, J.; Östlundh, L.; Mustafa, H.; Smith, J.E.M.; AlKaabi, J.M. Systematic review of the effects of pandemic confinements on body weight and their determinants. Br. J. Nutr. 2022, 127, 298–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daniel, M.M.; Liboredo, J.C.; Souza, T.C.d.M.; Anastácio, L.R.; Ferreira, A.R.S.; Ferreira, L.G. The Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Longitudinal Analysis of Body Weight Variations and Their Implications for Daily Habits. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2024, 21, 1510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, A.H.; Zhong, S.; Yang, H.; Jeong, J.; Lee, C. Impact of COVID-19 on physical activity: A rapid review. J. Glob. Health 2022, 12, 05003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kriaučionienė, V.; Grincaitė, M.; Raskilienė, A.; Petkevičienė, J. Changes in Nutrition, Physical Activity, and Body Weight among Lithuanian Students during and after the COVID-19 Pandemic. Nutrients 2023, 15, 4091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- The Republic of Türkiye Ministry of Health. Turkey Nutrition and Health Survey (TBSA). 2019. Available online: https://hsgm.saglik.gov.tr/depo/birimler/saglikli-beslenme-ve-hareketli-hayat-db/Dokumanlar/Kitaplar/Turkiye_Beslenme_ve_Saglik_Arastirmasi_TBSA_2017.pdf (accessed on 8 May 2025).

- Turkish Statistical Institute. Turkey Health Survey 2022. 2023. Available online: https://data.tuik.gov.tr/Bulten/Index?p=Turkiye-Health-Survey-2022-49747&dil=2 (accessed on 8 June 2025).

- Faul, F.; Erdfelder, E.; Lang, A.G.; Buchner, A. G*Power 3: A flexible statistical power analysis program for the social, behavioral, and biomedical sciences. Behav. Res. Methods 2007, 39, 175–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WHO. A Healthy Lifestyle—WHO Recommendations. 2010. Available online: https://www.who.int/europe/news-room/fact-sheets/item/a-healthy-lifestyle---who-recommendations (accessed on 8 May 2025).

- Anton, S.D.; Hida, A.; Heekin, K.; Sowalsky, K.; Karabetian, C.; Mutchie, H.; Barnett, T.E. Effects of popular diets without specific calorie targets on weight loss outcomes: Systematic review of findings from clinical trials. Nutrients 2017, 9, 822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Freire, R. Scientific evidence of diets for weight loss: Different macronutrient composition, intermittent fasting, and popular diets. Nutrition 2020, 69, 110549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayran, M.; Hayran, M. Sağlık Araştırmaları İçin Temel İstatistik, 2nd ed.; Omega Araştırma: Ankara, Türkiye, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual. Res. Psychol. 2006, 3, 77–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakaloudi, D.R.; Barazzoni, R.; Bischoff, S.C.; Breda, J.; Wickramasinghe, K.; Chourdakis, M. Impact of the first COVID-19 lockdown on body weight: A combined systematic review and a meta-analysis. Clin. Nutr. 2022, 41, 3046–3054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalligeros, M.; Shehadeh, F.; Mylona, E.K.; Benitez, G.; Beckwith, C.G.; Chan, P.A.; Mylonakis, E. Association of obesity with disease severity among patients with Coronavirus Disease 2019. Obesity 2020, 28, 1200–1204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simonnet, A.; Chetboun, M.; Poissy, J.; Raverdy, V.; Noulette, J.; Duhamel, A.; Labreuche, J.; Mathieu, D.; Pattou, F.; Jourdain, M.; et al. High prevalence of obesity in severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus-2 (SARS-COV-2) requiring invasive mechanical ventilation. Obesity 2020, 28, 1195–1199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griffin, T.; Grey, E.; Lambert, J.; Gillison, F.; Townsend, N.; Solomon-Moore, E. Life in lockdown: A qualitative study exploring the experience of living through the initial COVID-19 lockdown in the UK and its impact on diet, physical activity and mental health. BMC Public Health 2023, 23, 588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daly, M.; Robinson, E. Psychological distress and adaptation to the COVID-19 crisis. J. Psychiatr. Res. 2021, 136, 603–609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nour, T.Y.; Altintaş, K.H. Effect of the COVID-19 pandemic on obesity and it is risk factors: A systematic review. BMC Public Health 2023, 23, 1018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paltrinieri, S.; Bressi, B.; Costi, S.; Mazzini, E.; Cavuto, S.; Ottone, M.; De Panfilis, L.; Fugazzaro, S.; Rondini, E.; Giorgi Rossi, P. Beyond Lockdown: The Potential Side Effects of the SARS-CoV-2 Pandemic on Public Health. Nutrients 2021, 13, 1600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Çengel, B.; Karadavut, U. Covid 19 Pandemisinin Beslenme Alışkanlıklarına Etkisi. Sci. Tech. 21st Century 2020, 2, 39–46. [Google Scholar]

- Zachary, Z.; Brianna, F.; Brianna, L.; Garrett, P.; Jade, W.; Alyssa, D.; Mikayla, K. Self-quarantine and weight gain related risk factors during the COVID-19 pandemic. Obes. Res. Clin. Pract. 2020, 14, 210–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bisset, S.; Gauvin, L.; Potvin, L.; Paradis, G. Association of body mass index and dietary restraint with changes in eating behaviour throughout late childhood and early adolescence: A 5-year study. Public Health Nutr. 2007, 10, 780–789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Strien, T.; Herman, C.P.; Verheijden, M.W. Dietary restraint and body mass change: A 3-year follow-up study in a representative Dutch sample. Appetite 2014, 76, 44–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhutani, S.; Cooper, J.A.; Vandellen, M.R. Self-Reported changes in energy balance behaviors during COVID-19-related home confinement: A cross-sectional study of US adults. Obesity 2021, 29, 1909–1919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Scherer, N.; Felix, L.; Kuper, H. Prevalence of depression, anxiety and post-traumatic stress disorder in health care workers during the COVID-19 pandemic: A systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0246454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Kessel, R.; Kyriopoulos, I.; Wong, B.L.H.; Mossialos, E. The effect of the COVID-19 pandemic on digital health–seeking behavior: Big data interrupted time-series analysis of Google Trends. J. Med. Internet Res. 2023, 25, e42401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fappa, E.; Micheli, M. Content accuracy and readability of dietary advice available on webpages: A systematic review of the evidence. J. Hum. Nutr. Diet. 2025, 38, e13395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).