Transient Decrease in Nursing Workload in a Cardiology Intensive Care Unit During the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Brazilian Ecological Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

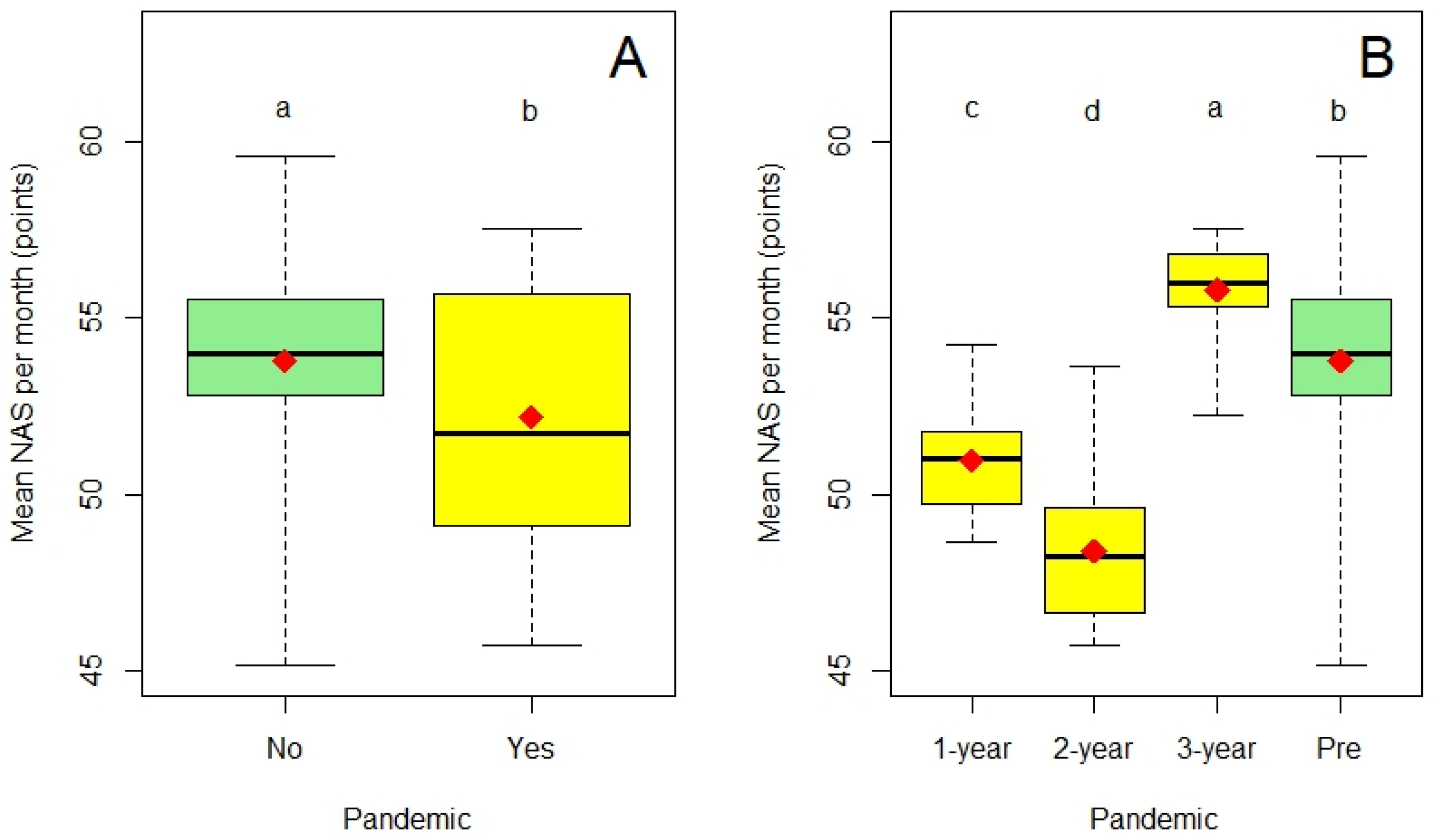

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| NAS | Nursing Activities Score |

| ICU | Intensive Care Unit |

| NAS-mm | Nursing Activities Score mean by month |

| 95%CI | 95% Confidence Interval |

References

- Ciotti, M.; Angeletti, S.; Minieri, M.; Giovannetti, M.; Benvenuto, D.; Pascarella, S.; Sagnelli, C.; Bianchi, M.; Bernardini, S.; Ciccozzi, M. COVID-19 Outbreak: An Overview. Chemotherapy 2020, 64, 215–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hoogendoorn, M.E.; Brinkman, S.; Bosman, R.J.; Haringman, J.; de Keizer, N.F.; Spijkstra, J.J. The impact of COVID-19 on nursing workload and planning of nursing staff on the Intensive Care: A prospective descriptive multicenter study. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 2021, 121, 104005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lucchini, A.; Villa, M.; Del Sorbo, A.; Pigato, I.; D’Andrea, L.; Greco, M.; Chiara, C.; Cesana, M.; Rona, R.; Giani, M. Determinants of increased nursing workload in the COVID-era: A retrospective analysis of prospectively collected data. Nurs. Crit. Care 2023, 29, 196–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nogueira, T.D.A.; Menegueti, M.G.; Perdoná, G.D.S.C.; Auxiliadora-Martins, M.; Fugulin, F.M.T.; Laus, A.M. Effect of nursing care hours on the outcomes of Intensive Care assistance. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0188241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brasil—Agência Nacional de Vigilância Sanitária. Resolução da Diretoria Colegiada No. 7, de 24 de Fevereiro de 2010. Dispõe Sobre os Requisitos Mínimos para Funcionamento de Unidades de Terapia Intensiva e dá Outras Providências; Diário Oficial da União. Available online: https://bvsms.saude.gov.br/bvs/saudelegis/anvisa/2010/res0007_24_02_2010.html (accessed on 28 July 2023).

- de Almeida Júnior, E.R.; de Oliveira, D.B.; dos Santos, G.R.; de Felice, R.O.; Gomes, F.A.; Mendes-Rodrigues, C. The 4-year experience of Nursing Activities Score use in a Brazilian cardiac intensive care unit. Int. J. Innov. Educ. Res. 2021, 9, 382–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lima, V.C.G.S.; Pimentel, N.B.L.; de Oliveira, A.M.; de Andrade, K.B.S.; dos Santos, M.L.S.C.; dos Santos Claro Fuly, P. Nursing workload in oncological intensive care in the COVID-19 pandemic: Retrospective cohort. Rev. Gaúcha Enferm. 2023, 44, e20210334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Batassini, É.; Beghetto, M.G. Comparing nursing workload for critically ill adults with and without COVID-19: Retrospective cohort study. Nurs. Crit. Care 2023, 29, 397–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patel, R.; Hainsworth, A.J.; Devlin, K.; Patel, J.H.; Karim, A. Frequency and severity of general surgical emergencies during the COVID-19 pandemic: Single-centre experience from a large metropolitan teaching hospital. Ann. R. Coll. Surg. Engl. 2020, 102, 457–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mauricio, C.C.R.; Serafim, C.T.R.; Novelli, M.C.; Lima, S.A.M. Profile of patients hospitalized in non-COVID intensive care unit. Rev. Recien. 2022, 12, 137–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Souza, J.L., Jr.; Teich, V.D.; Dantas, A.C.B.; Malheiro, D.T.; de Oliveira, M.A.; de Mello, E.S.; Cendoroglo Neto, M. Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on emergency department visits: Experience of a Brazilian reference center. Einstein 2021, 19, eAO6467. Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/34431853/ (accessed on 27 April 2025). [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Almeida, A.L.C.; do Espírito Santo, T.M.; Mello, M.S.S.; Cedro, A.V.; Lopes, N.L.; Ribeiro, A.P.M.R.; Mota, J.G.C.; Mendes, R.S.; Almeida, P.A.A.; Ferreira, M.A.; et al. Repercussions of the COVID-19 Pandemic on the Care Practices of a Tertiary Hospital. Arq. Bras. Cardiol. 2020, 115, 862–870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Santos, É.D.S.; Scorzoni, L.; de Carvalho, L.V.B.; Delineau, V.M.E.B.; de Carvalho, V.F.; Nicolosi, J.T. Nursing workload in adult intensive care units, general and COVID-19. J. Nurs. Health 2025, 15, e1527181. [Google Scholar]

- Cassiano, C.; Nogueira, L.S.; Araújo, A.C.U.; Lima, F.R.; Hanifi, N. Association between nursing workload and staff size with the occurrence of adverse events and deaths of patients with COVID-19: A retrospective cohort study. Nurs. Crit. Care 2025. ahead of print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Santos, W.C.; Lopes, M.C.B.T.; Vancini-Campanharo, C.R.; Boschetti, D.; da Silva Dias, S.O.; e Castro, M.C.N.; Piacezzi, L.H.V.; Batista, R.E.A. Nursing workload and severity of COVID-19 patients in the Intensive Care Unit. Rev. Esc. Enf. USP 2024, 58, e20240107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Buffon, M.R.; Severo, I.M.; Barcellos, R.D.A.; Azzolin, K.D.O.; Lucena, A.D.F. Critically ill COVID-19 patients: A sociodemographic and clinical profile and associations between variables and workload. Rev. Bras. Enf. 2022, 75 (Suppl. 1), e20210119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mendes-Rodrigues, C.; Costa, K.E.S.; Antunes, A.V.; Gomes, F.A.; Rezende, G.J.; Silva, D.V. Workload and nursing staff sizing in intensive care units. Rev. Aten. Saúde 2017, 15, 5–13. [Google Scholar]

- De Vries, N.; Maniscalco, L.; Matranga, D.; Bouman, J.; de Winter, J.P. Determinants of Intention to Leave Among Nurses and Physicians in a Hospital Setting During the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. PLoS ONE 2024, 19, 0300377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Mendes-Rodrigues, C.; Evaristo, J.S.D.; Jesus, A.L.L.d.; Oliveira Junior, G.V.d.; Braga, I.A.; Raponi, M.B.G.; Gomes, F.A. Transient Decrease in Nursing Workload in a Cardiology Intensive Care Unit During the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Brazilian Ecological Study. COVID 2025, 5, 78. https://doi.org/10.3390/covid5060078

Mendes-Rodrigues C, Evaristo JSD, Jesus ALLd, Oliveira Junior GVd, Braga IA, Raponi MBG, Gomes FA. Transient Decrease in Nursing Workload in a Cardiology Intensive Care Unit During the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Brazilian Ecological Study. COVID. 2025; 5(6):78. https://doi.org/10.3390/covid5060078

Chicago/Turabian StyleMendes-Rodrigues, Clesnan, Jully Silva Dias Evaristo, Ana Laura Lima de Jesus, Galeno Vieira de Oliveira Junior, Iolanda Alves Braga, Maria Beatriz Guimarães Raponi, and Fabiola Alves Gomes. 2025. "Transient Decrease in Nursing Workload in a Cardiology Intensive Care Unit During the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Brazilian Ecological Study" COVID 5, no. 6: 78. https://doi.org/10.3390/covid5060078

APA StyleMendes-Rodrigues, C., Evaristo, J. S. D., Jesus, A. L. L. d., Oliveira Junior, G. V. d., Braga, I. A., Raponi, M. B. G., & Gomes, F. A. (2025). Transient Decrease in Nursing Workload in a Cardiology Intensive Care Unit During the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Brazilian Ecological Study. COVID, 5(6), 78. https://doi.org/10.3390/covid5060078