Quality of Transition of Care from Hospital to Home for Patients Hospitalized for COVID-19

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Context

2.2. Study Setting and Timeframe

2.3. Population and Selection Criteria

2.4. Instrument, Study Variables, and Data Collection

2.5. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

4. Discussion

Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| COVID-19 | Infectious Disease Caused by the Novel Coronavirus |

| PEN | Postgraduate Program in Nursing |

| UFSC | Federal University of Santa Catarina |

| SC | Santa Catarina |

| CTM-15 | Care Transitions Measure |

| STROBE | Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology |

| ICU | Intensive Care Unit |

| ISBAR | Identify, Situation, Background, Recommendation |

References

- Acosta, A.M.; Lima, M.D.A.S.; Pinto, I.C.; Weber, L.A.F. Transição do cuidado de pacientes com doenças crônicas na alta da emergência para o domicílio. Rev. Gaúcha Enferm. 2020, 41, e20190155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bernardino, E.; Piexak, D.; Moraes, C.L.; Bubolz, B.; Magagnin, A.B. Cuidados de transição: Análise do conceito na gestão da alta hospitalar. Esc. Anna Nery 2020, 26, e20200435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anatchkova, M.D.; Barysauskas, V.M.; Kinney, R.L.; Kiefe, C.I.; Ash, C.A.S.; Lisa Lombardini, L.; Allison, J.L. Psychometric evaluation of the Care Transition Measure in TRACE-CORE: Do we need a better measure? J. Am. Heart Assoc. 2014, 3, e001053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Coleman, E.A.; Boult, C. Improving the quality of transitional care for persons with complex care needs. Am. Geriatr. Soc. Health Care Syst. Comm. 2003, 51, 556–557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bahr, S.J.; Weiss, M.E. Clarifying model for continuity of care: A concept analysis. Int. J. Nurs. Pract. 2018, 25, e12704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hervé, M.E.W.; Zucatti, P.B.; Lima, M.A.D.S. Transição do cuidado na alta da Unidade de Terapia Intensiva: Revisão de escopo. Rev. Lat. Am. Enferm. 2020, 28, e3325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lorenzini, E.; Molina, R.; Reigota, R.B.; Weingrill, E.A. Care transition from hospital to home: Cancer patients’ perspective. BMC Res. Notes 2020, 13, 267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Picolotto, A.; Barella, D.; Moraes, F.B.; Gasperi, P. The Patient Safety Culture of a Nursing Team From a Central Ambulatory. J. Fundam. Care Online 2019, 11, 333–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aued, G.K.; Bernardino, E.; Lapierre, J.; Dallaire, C. Atividades das enfermeiras de ligação na alta hospitalar: Uma estratégia para a continuidade do cuidado. Rev. Lat. Am. Enferm. 2019, 27, e3162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa, M.F.B.; Parreira, P.M.; Baptista, F.; Couto, L. The continuity of hospital nursing care for Primary Health Care in Spain. Rev. Esc. Enferm. USP 2019, 53, e03477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knihs, N.S.; Bertoncello, K.C.G.; Santos, J.L.; Rigo, L.; Gomes, E.C.; Goldani, L.F. Care transition for liver transplanted patients during the COVID-19 pandemic. Texto Contexto Enferm. 2020, 29, e20200191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weber, L.A.F.; Lima, M.A.D.S.; Acosta, A.M. Quality of care transition and its association with hospital readmission. Aquichan 2019, 19, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dantas, M.N.P.; Sousa, E.S.; Faustino, S.L.F.; Azevedo, I.C.; Santos, V.E.P. Transition of care in post-hospitalization patients due to COVID-19 in a hospital in northeastern Brazil. Rev. Bras. Enferm. 2023, 76, e20230030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leyenaar, J.K.; O’Brien, E.R.; Leslie, L.K. Importance and feasibility of transitional care for children with medical complexity: Results of a multistakeholder Delphi process. Acad. Pediatr. 2018, 18, 94–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elm, E.; Altman, D.G.; Egger, M.; Pocock, S.J.; Gøtzsche, P.C.; Vandenbroucke, J.P. The Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) statement: Guidelines for reporting observational studies. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 2008, 61, 344–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acosta, A.M.; Lima, M.D.A.S.; Pinto, I.C.; Weber, L.A.F. Brazilian version of the Care Transitions Measure: Translation and validation. Int. Nurs. Rev. 2017, 64, 379–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coleman, E.A.; Mahoney, E.; Parry, C. Assessing the quality of preparation for posthospital care from the patient’s perspective: The care transitions measure. Med. Care 2005, 43, 246–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rodrigues, C.D.; Lorenzini, E.; Romero, M.P.; Oelke, N.D.; Winter, V.D.B.; Kolankiewicz, A.C.B. Care transitions among oncological patients: From hospital to community. Rev. Esc. Enferm. USP 2023, 56, e20220308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cechinel-Peiter, C.; Lanzoni, G.M.M.; Mello, A.L.C.F.; Acosta, A.M.; Pina, J.C.; Andrade, S.R.; Oelke, N.D.; Santos, J.L.G. Quality of transitional care of children with chronic diseases: A cross-sectional study. Rev. Esc. Enferm. USP 2022, 56, e20210535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arrais, J.P.; Almeida, D.; Arrais, R.F. Transition of Care for Post-COVID-19 Patients: Sociodemographic and Clinical Profile and Associated Factors. Nurs. Forum 2023, 2023, 3505657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berghetti, L.; Danielle, M.B.A.; Winter, V.D.B.; Petersen, A.G.P.; Lorenzini, E.; Kolankiewicz, A.C.B. Transición del cuidado de pacientes con enfermedades crónicas y su relación con las características clínicas y sociodemográficas. Rev. Lat.-Am. Enferm. 2023, 31, e4013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flink, M.; Tessma, M.; Småstuen, M.C.; Lindblad, M.; Coleman, E.A.; Ekstedt, M. Measuring care transitions in Sweden: Validation of the care transitions measure. Int. J. Qual. Health Care 2018, 30, 291–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, X.; Chen, L.; Diao, Y.; Tian, L.; Liu, W.; Jiang, X. Validity and reliability of the Chinese version of the care transition measure. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0127403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwang, J.I.; Chung, J.H.; Kim, H.K. Psychometric properties of transitional care instruments and their relationships with health literacy: Brief PREPARED and Care Transitions Measure. Int. J. Qual. Health Care 2019, 31, 774–780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakshi, A.B.; Wee, S.L.; Tay, C.; Wong, L.M.; Leong, I.Y.O.; Merchant, R.A.; Luo, N. Validation of the care transition measure in multi-ethnic South-East Asia in Singapore. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2012, 12, 256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menezes, T.M.O.; Oliveira, A.L.B.; Santos, L.B.; Freitas, R.A.; Pedreira, L.C.; Veras, S.M.C.B. Cuidados de transição hospitalar à pessoa idosa: Revisão integrativa. Rev. Bras. Enferm. 2019, 72 (Suppl. S2), 307–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castro, C.C.S.P.; Marques, M.C.M.P.; Vaz, C.R.O.T. Comunicação na transição de cuidados de enfermagem em um serviço de emergência de Portugal. Cogitare Enferm. 2022, 27, e81767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loerinc, L.B.; Scheel, A.M.; Evans, S.J.M.; O’Keefe, G.A.; O’Keefe, J.B. Discharge characteristics and care transitions of hospitalized patients with COVID-19. Healthcare 2021, 9, 100512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takahashi, P.Y.; Chandra, A.; McCoy, R.G.; Borkenhagen, L.S.; Larson, M.E.; Thorsteinsdottir, B.; Hickman, J.A.; Swanson, K.M.; Hanson, G.J.; Naessens, J.M. Outcomes of a Nursing Home-to-Community Care Transition Program. J. Am. Med. Dir. Assoc. 2021, 22, 2440–2446.e2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Mean (SD) | Min–Max | P50 [P25; P75] | N | Alpha | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| General CTM | 52.97 (9.68) | 31–87 | 55.56 [46.15; 60.00] | 201 | 0.874 |

| Preparation for self-management | 58.31(13.58) | 24–100 | 61.90 [47.62; 66.67] | 201 | 0.895 |

| Understanding of medication | 53.66 (9.14) | 33–100 | 55.56 [44.44; 55.56] | 196 | 0.416 |

| Preferences assured | 52.47 (13.40) | 11–100 | 55.56 [44.44; 66.67] | 200 | 0.604 |

| Care plan | 34.00 (6.16) | 8–100 | 33.33 [33.33; 33.33] | 200 | 0.591 |

| CATEGORIES | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Don’t Know/Don’t Remembe/Not Applicable | Strongly Agree | Agree | Strongly Disagree | Disagree | Mean (SD) | |

| n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | ||

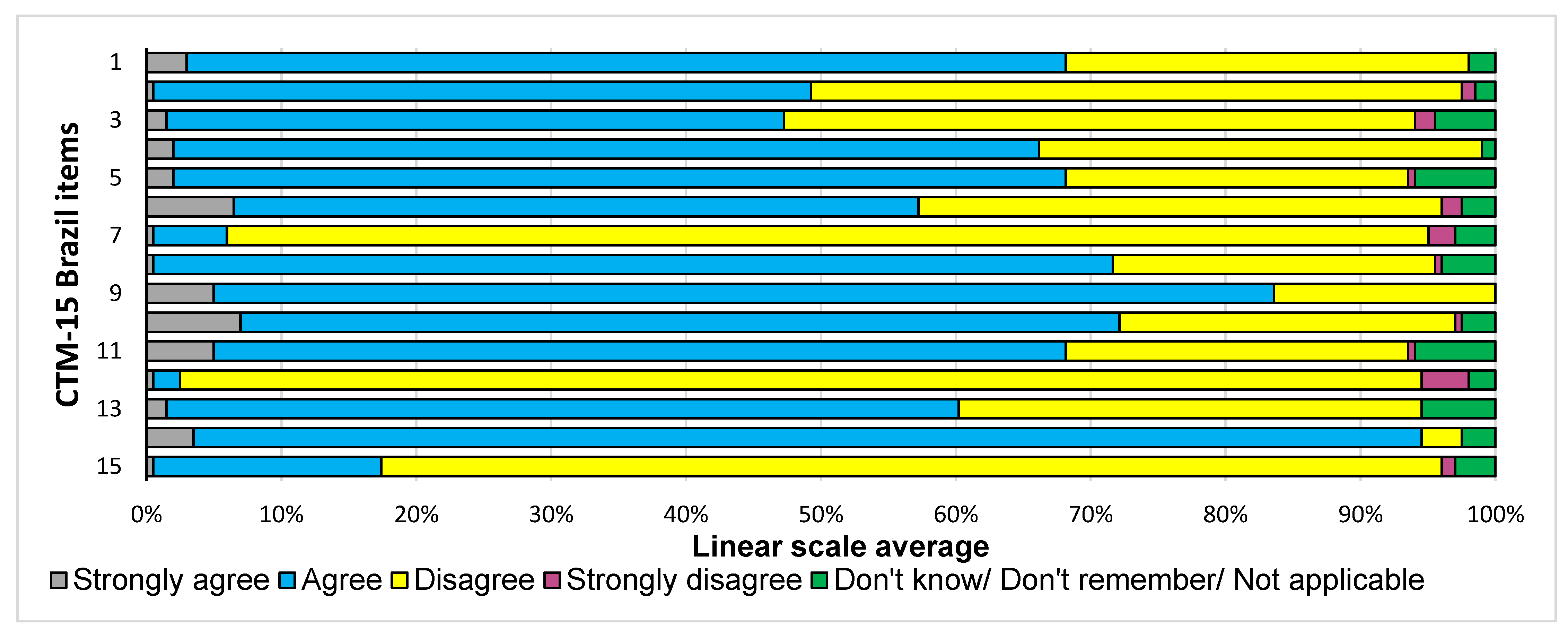

| Item 1: Before leaving the hospital, the healthcare team and I agreed on goals for my health and how they would be achieved. | 4 (2) | 0 (0) | 60 (29.9) | 131 (65.2) | 6 (3) | 57.53 (17.04) |

| Item 2: The hospital staff considered my preferences and those of my family or caregiver in deciding what my health needs would be after I left the hospital. | 3 (1.5) | 2 (1) | 97 (48.3) | 98 (48.8) | 1 (0.5) | 49.83 (17.69) |

| Item 3- The hospital staff considered my preferences and those of my family or caregiver in deciding where my health needs would be met after I left the hospital. | 9 (4.5) | 3 (1.5) | 94 (46.8) | 92 (45.8) | 3 (1.5) | 49.83 (18.68) |

| Item 4: When I left the hospital, I had all the information I needed so that I could look after myself. | 2 (1) | 0 (0) | 66 (32.8) | 129 (64.2) | 4 (2) | 56.28 (16.86) |

| Item 5: When I left the hospital, I clearly understood how to look after my health. | 12 (6) | 1 (0.5) | 51 (25.4) | 133 (66.2) | 4 (2) | 58.02 (16.54) |

| Item 6: When I left the hospital, I clearly understood the warning signs and symptoms I should look out for to monitor my health condition. | 5 (2.5) | 3 (1.5) | 78 (38.8) | 102 (50.7) | 13 (6.5) | 54.59 (20.98) |

| Item 7: When I left the hospital, I received a written, legible, and easy-to-understand plan that described how all my health needs would be met. | 6 (3) | 4 (2) | 179 (89.1) | 11 (5.5) | 1 (0.5) | 34.87 (10.32) |

| Item 8: When I left the hospital, I had a good understanding of my health condition and what could make it better or worse. | 8 (4) | 1 (0.5) | 48 (23.9) | 143 (71.1) | 1 (0.5) | 58.20 (15.32) |

| Item 9: When I left the hospital, I had a good understanding of what I was responsible for in terms of looking after my health. | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 33 (16.4) | 158 (78.6) | 10 (5) | 62.85 (14.98) |

| Item 10: When I left the hospital, I felt confident that I knew what to do to look after my health. | 5 (2.5) | 1 (0.5) | 50 (24.9) | 131 (65.2) | 14 (7) | 60.20 (18.59) |

| Item 11: When I left the hospital, I felt confident that I would be able to do the things I needed to do to look after my health. | 12 (6) | 1 (0.5) | 51 (25.4) | 127 (63.2) | 10 (5) | 59.08 (18.06) |

| Item 12: When I left the hospital, I was given a written, legible, and easy-to-understand list of appointments or tests that I needed to attend within the next few weeks. | 4 (2) | 7 (3.5) | 185 (92) | 4 (2) | 1 (0.5) | 33.16 (9.22) |

| Item 13: When I left the hospital, I clearly understood why I was taking each of my medications. | 11 (5.5) | 0 (0) | 69 (34.3) | 118 (58.7) | 3 (1.5) | 55.09 (16.99) |

| Item 14: When I left the hospital, I clearly understood how to take each of my medicines, including the quantity and timings. | 5 (2.5) | 0 (0) | 6 (3) | 183 (91) | 7 (3.5) | 66.84 (8.60) |

| Item 15: When I left the hospital, I clearly understood the possible side effects of each of my medications. | 6 (3) | 2 (1) | 158 (78.6) | 34 (16.9) | 1 (0.5) | 39.15 (13.97) |

| Preparation for Self-Management | Understanding of Medication | Preferences Secured | Care Plan | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean (SD) (n) | p | Mean (SD) (n) | p | Mean (SD) (n) | p | Mean (SD) (n) | p | |

| Influenza 1 | ||||||||

| Negative | 60.0 (13.7) (81) | 0.068 | 53.9 (8.5) (78) | 0.030 | 54.7 (12.9) (81) | 0.283 | 33.3 (0.0) (81) | 0.129 |

| Positive | 55.0 (13.0) (35) | 50.2 (7.4) (33) | 51.7 (15.5) (35) | 32.4 (5.6) (35) | ||||

| First hospitalization 1 | ||||||||

| No | 59.4 (16.3) (20) | 0.695 | 53.9 (11.0) (20) | 0.897 | 50.0 (11.7) (20) | 0.377 | 33.3 (0.0) (20) | 0.695 |

| Yes | 58.1 (13.5) (173) | 53.6 (9.1) (168) | 52.8 (13.6) (172) | 34.1 (8.8) (172) | ||||

| Other hospitalization 3 | ||||||||

| 2nd hospitalization | 64.9 (12.7) (7) | 0.351 | 55.6 (6.4) (7) | 0.393 | 46.0 (11.9) (7) | 0.275 | 33.3 (0.0) (7) | >0.999 |

| 3rd hospitalization | 56.5 (17.7) (13) | 53.0 (13.0) (13) | 52.1 (11.5) (13) | 33.3 (0.0) (13) | ||||

| Severity of illness 2 | ||||||||

| Moderate | 61.9 (11.9) (39) | 0.149 | 53.4 (10.6) (38) | 0.417 | 55.8 (11.0) (39) | 0.082 | 33.8 (9.0) (39) | 0.201 |

| Critical | 58.2 (12.2) (50) | 54.0 (7.7) (47) | 53.2 (13.3) (50) | 33.0 (2.4) (50) | ||||

| Severe | 56.7 (13.5) (51) | 55.9 (10.0) (51) | 49.7 (14.0) (50) | 36.3 (13.8) (50) | ||||

| Hypertension 1 | ||||||||

| No | 56.9 (14.4) (105) | 0.131 | 53.3 (9.1) (101) | 0.575 | 50.7 (12.7) (104) | 0.058 | 34.0 (9.0) (104) | 0.963 |

| Yes | 59.8 (12.6) (96) | 54.0 (9.2) (95) | 54.3 (13.9) (96) | 34.0 (7.2) (96) | ||||

| Diabetes mellitus 1 | ||||||||

| No | 58.1 (13.2) (140) | 0.783 | 53.5 (8.7) (135) | 0.790 | 52.7 (13.4) (139) | 0.744 | 34.2 (9.0) (139) | 0.653 |

| Yes | 58.7 (14.5) (61) | 53.9 (10.2) (61) | 52.0 (13.5) (61) | 33.6 (5.7) (61) | ||||

| Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease 3 | ||||||||

| No | 58.2 (13.5) (200) | - | 53.6 (9.1) (195) | - | 52.3 (13.2) (199) | - | 34.1 (8.1) (199) | - |

| Yes | 81.0 (0.0) (1) | 66.7 (0.0) (1) | 88.9 (0.0) (1) | 16.7 (0.0) (1) | ||||

| Asthma 1 | ||||||||

| No | 57.9 (13.7) (184) | 0.158 | 53.5 (9.3) (180) | 0.584 | 52.1 (13.4) (183) | 0.230 | 34.2 (8.4) (183) | 0.386 |

| Yes | 62.8 (11.6) (17) | 54.9 (7.6) (16) | 56.2 (13.3) (17) | 32.4 (4.0) (17) | ||||

| Chronic respiratory disease 3 | ||||||||

| No | 58.2 (13.7) (197) | 0.647 | 53.7 (9.1) (192) | 0.798 | 52.5 (13.5) (196) | 0.993 | 34.0 (8.2) (196) | 0.847 |

| Yes | 61.9 (6.7) (4) | 52.8 (10.6) (4) | 52.8 (10.6) (4) | 33.3 (0.0) (4) | ||||

| Chronic heart failure 1 | ||||||||

| No | 58.4 (13.6) (186) | 0.779 | 53.9 (9.3) (181) | 0.263 | 52.1 (13.6) (185) | 0.208 | 34.1 (8.5) (185) | 0.743 |

| Yes | 57.4 (13.1) (15) | 51.1 (6.7) (15) | 56.7 (10.3) (15) | 33.3 (0.0) (15) | ||||

| Obesity 1 | ||||||||

| No | 58.8 (14.6) (87) | 0.662 | 54.4 (8.8) (85) | 0.334 | 52.4 (12.8) (86) | 0.940 | 33.3 (8.4) (87) | 0.312 |

| Yes | 57.9 (12.8) (114) | 53.1 (9.4) (111) | 52.5 (13.9) (114) | 34.5 (7.9) (113) | ||||

| Smoking 3 | ||||||||

| No | 58.3 (13.7) (193) | 0.960 | 53.6 (9.2) (188) | 0.411 | 52.6 (13.4) (192) | 0.489 | 34.1 (7.9) (192) | 0.770 |

| Yes | 58.5 (9.1) (8) | 55.6 (8.4) (8) | 50.0 (14.5) (8) | 31.3 (13.9) (8) | ||||

| Does physical exercise 1 | ||||||||

| No | 59.0 (13.7) (151) | 0.219 | 53.4 (9.1) (148) | 0.456 | 53.5 (13.4) (150) | 0.056 | 33.4 (6.2) (151) | 0.091 |

| Yes | 56.3 (13.2) (50) | 54.5 (9.4) (48) | 49.3 (13.1) (50) | 35.7 (12.3) (49) | ||||

| Physical exercise 4 | ||||||||

| 1x a week | 59.1 (2.8) (2) | 0.517 | 55.6 (0.0) (2) | 0.628 | 44.4 (0.0) (2) | 0.837 | 33.3 (0.0) (2) | 0.916 |

| 2x a week | 52.2 (14.1) (15) | 52.4 (6.8) (14) | 48.1 (11.6) (15) | 34.4 (4.3) (15) | ||||

| 3x or more a week | 57.9 (13.1) (33) | 55.4 (10.6) (32) | 50.2 (14.2) (33) | 36.5 (14.9) (32) | ||||

| No. of comorbidities 2 | ||||||||

| None | 55.4 (16.5) (33) | 0.536 | 54.3 (10.7) (32) | 0.964 | 47.2 (13.2) (32) | 0.107 | 32.8 (13.5) (33) | 0.272 |

| 1 comorbidity | 58.8 (12.7) (73) | 53.3 (7.8) (70) | 53.3 (12.7) (73) | 34.3 (5.5) (72) | ||||

| 2 comorbidities | 58.2 (13.1) (54) | 53.6 (8.7) (53) | 54.1 (12.7) (54) | 35.5 (8.0) (54) | ||||

| 3 or more | 59.9 (13.2) (41) | 53.8 (10.7) (41) | 52.8 (15.1) (41) | 32.5 (6.4) (41) | ||||

| Preparation for Self-Management | Understanding of Medication | Preferences Secured | Care Plan | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean (SD) (n) | p | Mean (SD) (n) | p | Mean (SD) (n) | p | Mean (SD) (n) | p | |

| Sex 1 | ||||||||

| Male | 58.4 (13.9) (111) | 0.902 | 53.6 (8.9) (109) | 0.880 | 52.7 (13.2) (110) | 0.812 | 33.3 (9.6) (110) | 0.202 |

| Female | 58.2 (13.3) (90) | 53.8 (9.5) (87) | 52.2 (13.8) (90) | 34.8 (5.9) (90) | ||||

| Age 2 | ||||||||

| 21 to 59 | 57.8 (14.1) (120) | 0.822 | 53.6 (9.2) (116) | 0.984 | 52.3 (13.1) (120) | 0.966 | 33.9 (7.2) (119) | 0.655 |

| 60 to 69 | 58.7 (10.3) (40) | 53.6 (7.5) (40) | 52.8 (13.7) (40) | 33.3 (7.5) (40) | ||||

| ≥70 | 59.3 (15.1) (41) | 53.9 (10.7) (40) | 52.8 (14.3) (40) | 35.0 (11.1) (41) | ||||

| Spouse 1 | ||||||||

| Single/widowed/divorced | 57.1 (13.5) (80) | 0.327 | 53.2 (8.7) (79) | 0.597 | 52.3 (14.3) (79) | 0.850 | 33.3 (9.2) (79) | 0.352 |

| Married/stable union | 59.1 (13.6) (121) | 53.9 (9.5) (117) | 52.6 (12.8) (121) | 34.4 (7.4) (121) | ||||

| Race 1 | ||||||||

| White | 58.4 (14.0) (160) | 0.835 | 54.0 (9.6) (157) | 0.294 | 52.2 (13.5) (160) | 0.501 | 34.0 (7.7) (159) | 0.898 |

| Black + Brown | 57.9 (12.1) (41) | 52.3 (7.2) (39) | 53.8 (13.2) (40) | 34.1 (9.8) (41) | ||||

| Income ranges 2 | ||||||||

| Below 1 m.w. | 60.7 (13.9) (32) | 0.310 | 55.6 (8.5) (32) | 0.059 | 52.9 (16.4) (31) | 0.609 | 32.8 (6.7) (32) | 0.808 |

| Between 1 and 3 m.w. | 56.8 (13.9) (120) | 52.1 (8.6) (118) | 51.7 (13.0) (120) | 33.6 (8.4) (120) | ||||

| Above 3 m.w. | 59.5 (11.3) (18) | 55.6 (5.7) (16) | 54.9 (11.7) (18) | 34.3 (6.9) (18) | ||||

| Family income bracket 3 | ||||||||

| Below 1 m.w. | 58.1 (13.2) (10) | 0.874 | 52.8 (8.8) (10) | 0.763 | 54.4 (12.2) (10) | 0.455 | 36.7 (7.0) (10) | 0.529 |

| Between 1 and 3 m.w. | 57.8 (13.9) (100) | 54.8 (10.2) (99) | 50.9 (13.3) (99) | 34.0 (10.0) (100) | ||||

| Between 4 and 6 m.w. | 59.2 (12.0) (54) | 52.4 (7.0) (53) | 54.5 (13.4) (54) | 34.0 (4.5) (54) | ||||

| Above 7 m.w. | 56.7 (15.2) (11) | 53.1 (7.4) (9) | 53.5 (13.0) (11) | 34.8 (11.7) (11) | ||||

| Read 4 | ||||||||

| No | 54.0 (10.4) (4) | 0.320 | 47.2 (5.6) (4) | 0.096 | 52.8 (10.6) (4) | 0.993 | 33.3 (0.0) (4) | 0.847 |

| Yes | 58.4 (13.6) (197) | 53.8 (9.2) (192) | 52.5 (13.5) (196) | 34.0 (8.2) (196) | ||||

| Schooling 2 | ||||||||

| Up to 4th grade | 59.9 (11.4) (28) | 0.299 | 52.9 (8.4) (27) | 0.511 | 54.9 (11.4) (27) | 0.233 | 31.0 (9.8) (28) | 0.160 |

| 5th to 8th grade | 62.0 (15.0) (26) | 55.3 (10.9) (26) | 54.7 (15.4) (26) | 35.3 (5.4) (26) | ||||

| HS | 56.5 (14.2) (77) | 52.9 (7.8) (76) | 50.1 (13.3) (77) | 34.0 (8.3) (77) | ||||

| IHE/CHE/ specialization | 58.3 (13.4) (64) | 54.7 (10.3) (61) | 53.3 (13.6) (64) | 34.9 (8.3) (63) | ||||

| Remuneration 1 | ||||||||

| Does not work | 59.7 (13.1) (42) | 0.464 | 54.2 (11.5) (40) | 0.693 | 53.8 (11.7) (42) | 0.459 | 35.0 (6.2) (41) | 0.400 |

| Works/retired/pensioner | 57.9 (13.7) (159) | 53.5 (8.5) (156) | 52.1 (13.8) (158) | 33.8 (8.6) (159) | ||||

| Hospitalization sector | ||||||||

| COVID-19 hospitalization | 58.3 (13.6) (201) | - | 53.7 (9.1) (196) | - | 52.5 (13.4) (200) | - | 34.0 (8.2) (200) | - |

| Status 4 | ||||||||

| Discharged | 58.5 (13.4) (198) | 0.039 | 53.7 (9.2) (193) | 0.231 | 52.6 (13.3) (197) | 0.321 | 34.0 (8.2) (197) | 0.868 |

| Transferred | 42.6 (16.0) (3) | 48.1 (6.4) (3) | 44.4 (19.2) (3) | 33.3 (0.0) (3) | ||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Jesus, E.R.d.; Boell, J.E.W.; Malkiewiez, M.M.; da Silva, M.B.; Fabrizzio, G.C.; Schmidt, C.R.; Alpirez, L.A.; Ferreira, D.S.; Lorenzini, E. Quality of Transition of Care from Hospital to Home for Patients Hospitalized for COVID-19. COVID 2025, 5, 50. https://doi.org/10.3390/covid5040050

Jesus ERd, Boell JEW, Malkiewiez MM, da Silva MB, Fabrizzio GC, Schmidt CR, Alpirez LA, Ferreira DS, Lorenzini E. Quality of Transition of Care from Hospital to Home for Patients Hospitalized for COVID-19. COVID. 2025; 5(4):50. https://doi.org/10.3390/covid5040050

Chicago/Turabian StyleJesus, Edna Ribeiro de, Julia Estela Willrich Boell, Michelle Mariah Malkiewiez, Marinalda Boneli da Silva, Greici Capellari Fabrizzio, Catiele Raquel Schmidt, Luana Amaral Alpirez, Darlisom Sousa Ferreira, and Elisiane Lorenzini. 2025. "Quality of Transition of Care from Hospital to Home for Patients Hospitalized for COVID-19" COVID 5, no. 4: 50. https://doi.org/10.3390/covid5040050

APA StyleJesus, E. R. d., Boell, J. E. W., Malkiewiez, M. M., da Silva, M. B., Fabrizzio, G. C., Schmidt, C. R., Alpirez, L. A., Ferreira, D. S., & Lorenzini, E. (2025). Quality of Transition of Care from Hospital to Home for Patients Hospitalized for COVID-19. COVID, 5(4), 50. https://doi.org/10.3390/covid5040050