Press and School Violence: Subjective Theories in the Post-Pandemic Narratives in Chilean Online Newspapers

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Conceptualization of School Violence

1.2. Collective Subjective Theories and Mass Media

1.3. Agenda Setting and Framing in News Construction

2. Methods

2.1. Data Collection Procedures

2.2. Data Analysis

2.2.1. Descriptive Analysis

2.2.2. Interpretive Analysis

3. Results

“Constant episodes of school violence and threat of massacre at Quinta Normal school concern the Ministry of Education”,

“The employee of a warehouse located in front of the Confederación Suiza School (…) clarifies that protests at the school are an everyday occurrence”.(LUN, 22 November 2022)

“With high dropout and absenteeism rates resulting from the COVID-19 pandemic, amid a climate of violence led by hooded individuals throwing Molotov cocktails at the police…”.(El Mostrador, 16 November 2022)

“Not overloading the academic aspect, prioritizing a space for meeting and emotional support, maintaining self-care measures, and recovering sleep routines are key aspects for this return to face-to-face classes that many children and young people are experiencing this week.”.(1 March 2022, El Mostrador)

“This whole process has been even more complex for students who have graduated from high school in the last three years, who have also had to deal with the ravages of the pandemic.”.(LUN, 29 November 2022)

“In addition to this, local efforts are being made with stakeholders, such as working groups with provincial education departments, municipalities, and schools, to design reconnection initiatives and share best practices.”(El Mostrador, 16 November 2022)

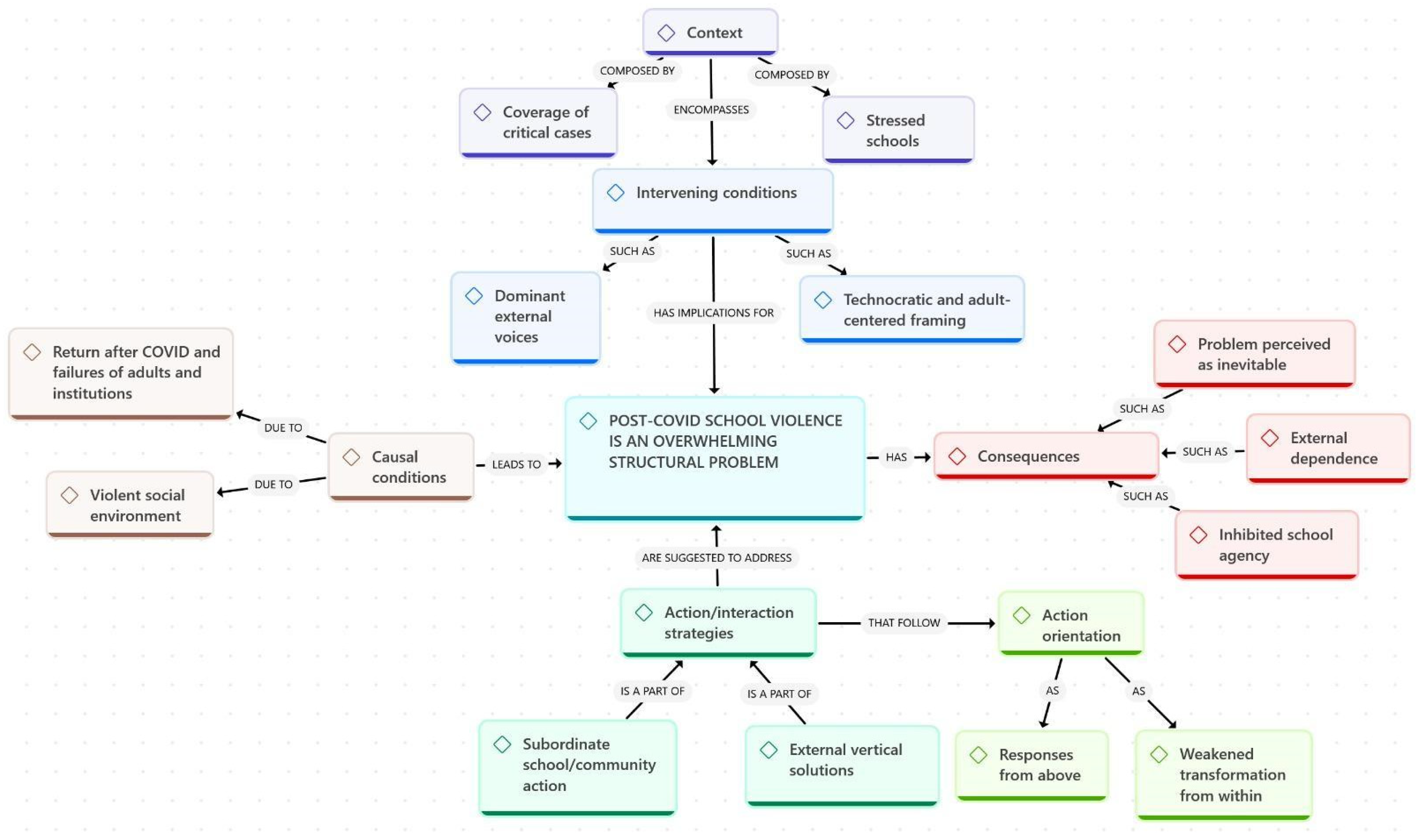

Relational Analysis

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- EMOL. Denuncias en Colegios por Convivencia Escolar Aumentan un 40% en 2025, Según Datos del Mineduc. Emol. Available online: https://www.emol.com/noticias/Nacional/2025/09/07/1176991/denuncias-colegios-educacion-convivencia-escolar.html (accessed on 7 September 2025).

- Ministerio de Educación. Establecimientos de Todo el País se Suman a la Jornada Nacional “Presentes Contra la Violencia”. Available online: https://www.mineduc.cl/establecimientos-de-todo-el-pais-se-suman-a-la-jornada-nacional-presentes-contra-la-violencia/ (accessed on 12 August 2025).

- Ministerio de Educación. Ministro Nicolás Cataldo presenta la Cuenta Pública 2025 del Mineduc. Available online: https://www.mineduc.cl/ministro-nicolas-cataldo-presenta-la-cuenta-publica-2025-del-mineduc/ (accessed on 11 July 2025).

- Ministerio de Educación. Plan de Reactivación Educativa. 2023. Available online: https://reactivacioneducativa.mineduc.cl/wp-content/uploads/sites/127/2023/11/Plan-de-Reactivacion-Educativa.Formalizado-2023.pdf (accessed on 1 January 2024).

- Senado de Chile. Convivencia Escolar: Sala Aprueba en General Proyecto que Busca Prevenir Violencia en Establecimientos Educacionales. Available online: https://www.senado.cl/comunicaciones/noticias/convivencia-escolar-sala-aprueba-en-general-proyecto-que-busca-prevenir (accessed on 12 September 2025).

- OECD. Education at a Glance 2022; OECD Indicators; OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Instituto Nacional de Derechos Humanos (INDH). Situación de los Derechos Humanos en Chile 2022: Informe Anual [en Línea]. Santiago: INDH. 2022. Available online: https://bibliotecadigital.indh.cl/bitstreams/ad9c06f7-716a-43f8-b3f6-90a880756220/download (accessed on 9 April 2024).

- Instituto Nacional de Derechos Humanos (INDH). En el día contra el bullying: Informe Anual 2022 Mostró una Creciente Violencia en el Retorno a Clases Luego de la Pandemia [en Línea]. Santiago: INDH. 2022. Available online: http://surl.li/clbhne (accessed on 23 February 2023).

- Ministerio de Educación. Presentes Contra la Violencia. 2025. Available online: https://presentescontralaviolencia.mineduc.cl/assets/download/Convivencia,%20violencia%20y%20actos%20constitutivos.pdf (accessed on 1 November 2025).

- UNESCO. Entornos de Aprendizaje Seguros. Available online: https://www.unesco.org/es/health-education/safe-learning-environments (accessed on 5 November 2024).

- López-Castedo, A.; García, D.; Alonso, J.; Rosales, E. Expressions of school violence in adolescence. Psicothema 2018, 30, 395–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernández, R.; Saravia, M. Generalidades del Acoso Escolar: Una Revisión de Conceptos. Rev. Investig. Apunt. Psicológicos 2016, 1, 30–40. Available online: https://repositorio.usil.edu.pe/entities/publication/ea01b863-26b6-4f54-ab59-e2467f490ec7 (accessed on 10 April 2024).

- Neut, P. Contra la Escuela. Autoridad, Democratización y Violencias en el Escenario Educativo Chileno; LOM Ediciones: Santiago, Chile, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Medina, D.C.M.; Paredes, D.A.S. Violencia Escolar en adolescentes: Una revisión sistemática. Rev. Investig. Enlace Univ. 2021, 20, 10–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Velázquez, L.M. Convivencia y violencia a través de las Tecnologías de la Información y Comunicación. In Convivencia, Disciplina y Violencia en las Escuelas 2002–2011; En Furlán, A., Spitzer, T.C., Eds.; ANUIES-COMIE Colección Estados del Conocimiento: Mexico City, Mexico, 2013; pp. 261–278. Available online: https://www.comie.org.mx/v5/sitio/wp-content/uploads/2020/08/Convivencia-disciplina-y-violencia-en-las-escuelas.pdf (accessed on 11 April 2023).

- Carhuaz, E.O.; Yupanqui-Lorenzo, D. Violencia escolar y funcionalidad familiar en adolescentes con riesgo de deserción escolar. Rev. Científica UCSA 2020, 7, 3–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herrera-López, M.; Benavides Mdel, R.; Ortiz, G.P.; Ruano, M.A. Effects of parenting guidelines on the roles of school violence. Psychol. Soc. Educ. 2022, 14, 23–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prieto-García, M. Violencia escolar y vida cotidiana en la escuela secundaria. Rev. Mex. Investig. Educ. 2005, 10, 1005–1026. Available online: https://www.redalyc.org/pdf/140/14002703.pdf (accessed on 13 April 2025).

- Varela, J.J.; Zimmerman, M.A.; Ryan, A.M.; Stoddard, S.A.; Heinze, J.E.; Alfaro, J. Life satisfaction, school satisfaction, and school violence: A mediation analysis for Chilean adolescent victims and perpetrators. Child Indic. Res. 2018, 11, 487–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- dos Reis, J.B.; Dayrell, J. Experiências juvenis contemporâneas: Reflexões teóricas e metodológicas sobre socialização e individualização. Educação 2020, 45, 71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olea, B. @bastimapache]. Cobertura de Delincuencia en Prensa Versus Estadísticas de Delincuencia. [Foto] Twitter. Available online: https://twitter.com/bastimapache/status/1777805638266949662/photo/1 (accessed on 9 April 2024).

- Rojas-Andrade, R.; López Leiva, V.; Varela, J.J.; Soto García, P.; Álvarez, J.P.; Ramírez, M.T. Feasibility, acceptability, and appropriability of a national whole-school program for reducing school violence and improving school coexistence. Front. Psychol. 2024, 15, 1395990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jodelet, D.; Moscovici, S. Folies et Représentations Sociales; Presses Universitaires de France: Paris, France, 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Santander, P. Por qué y cómo hacer Análisis de Discurso. Cinta Moebio 2011, 41, 207–224. Available online: https://cintademoebio.uchile.cl/index.php/CDM/article/view/18183 (accessed on 13 April 2025).

- Colás, P.; Villaciervos, P. La interiorización de los estereotipos de género en jóvenes y adolescentes. Rev. Investig. Educ. 2007, 25, 35–58. Available online: https://revistas.um.es/rie/article/view/96421 (accessed on 14 April 2025).

- Catalán, J. Hacia la formulación de una teoría general de las teorías subjetivas. Psicoperspectivas 2016, 15, 53–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandoval, J.; Cuadra, D. El abordaje psicológico de la vulnerabilidad escolar desde una dimensión subjetiva: El psicólogo escolar entre la estructura y la agencia. In Psicólogos en la Escuela: El Replanteo de un rol Confuso Volumen II; Leal-Soto, F., Coord.; Noveduc: Buenos Aires, Argentina, 2018; pp. 49–84. [Google Scholar]

- Checa, L. Del Encuadre a los Marcos Estructurales: Teorías de Análisis de Medios y Contexto Socio-Cultural. F@Ro Rev. Teórica Dep. Cienc. Comun. 2018, 2, 3–25. Available online: https://www.revistafaro.cl/index.php/Faro/article/view/266/196 (accessed on 14 April 2025).

- Entman, R. Framing: Toward clarification of a fractured paradigm. J. Commun. 1993, 43, 51–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moscovici, S. El Psicoanálisis, su Imagen y su Público; Huemul S.A.: Buenos Aires, Argentina, 1961. [Google Scholar]

- Iyengar, S. Is Anyone Responsible? How Television Frames Political Issues; The University of Chicago Press: Chicago, IL, USA, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Semetko, H.; Valkenburg, P. Framing European politics: A content analysis of press and television news. J. Commun. 2000, 50, 93–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Groeben, N.; Scheele, B. Dialogue-hermeneutic method and the “research program subjective theories”. Forum Qual. Sozialforschung Forum: Qual. Soc. Res. 2001, 2, 10. [Google Scholar]

- Flick, U. Everyday knowledge in social psychology. In The Psychology of the Social; Flick, U., Ed.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1998; pp. 41–59. [Google Scholar]

- Goller, A.; Markert, J. Teacher educators’ subjective theories on education for sustainable development in higher education. Environ. Educ. Res. 2025, 31, 1335–1355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Köb, S.; Janz, F. Teachers’ subjective theories regarding social dynamics management and social participation of students with Intellectual Disabilities in inclusive classrooms. Int. J. Incl. Educ. 2023, 27, 1530–1543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flick, U. An Introduction to Qualitative Research; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Ardévol, A. Framing o teoría del encuadre en comunicación. Orígenes, desarrollo y panorama actual en España. Rev. Lat. Comun. Soc. 2015, 70, 423–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reese, S.D.; Gandy, O.H., Jr.; Grant, A.E. (Eds.) Framing Public Life: Perspectives on Media and Our Understanding of the Social World, 1st ed.; Routledge: Abingdon-on-Thames, UK, 2001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scheufele, D. Framing as a theory of media effects. J. Commun. 1999, 49, 103–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goffman, E. Frame Analysis: Los Marcos de la Experiencia; CIS: Madrid, Spain, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Fernández-Ramos, M.; Antón, M. Estereotipos de las personas mayores y de género en la prensa digital: Estudio empírico desde la teoría del framing. Prism. Soc. 2018, 21, 317–337. Available online: https://dialnet.unirioja.es/servlet/articulo?codigo=6521444 (accessed on 25 January 2025).

- Angélico, R.; Dikenstein, V.; Fischberg, S.; Maffeo, F. El feminicidio y la violencia de género en la prensa argentina: Un análisis de voces, relatos y actores. Univ. Humanística 2014, 78, 281–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cegarra, J. Fundamentos teórico epistemológicos de los imaginarios sociales. Cinta Moebio 2012, 43, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loscertales, F. Los Medios de Comunicación con Mirada de Género. Junta de Andalucía; Instituto Andaluz de la Mujer: Andalusia, Spain, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Browne, M.; Rodríguez-Pastene, F. Nuevas miradas para viejos estereotipos mediáticos de la infancia y la adolescencia (169–197). In Niños, Niñas y Adolescentes en Medios de Comunicación: Construcción de Estereotipos en Prensa Escrita y Televisión en Chile; Fondo de las Naciones Unidas para la Infancia, UNICEF: New York, NY, USA, 2019; Available online: https://www.unicef.org/chile/media/2836/file/ninos_ninas_y_adolescentes_en_medios_de_comunicacion.pdf (accessed on 25 January 2025).

- McCombs, M.; Shaw, D.L. The agenda-setting function of mass media. Public Opin. Q. 1972, 36, 176–187. Available online: http://www.jstor.org/stable/2747787 (accessed on 25 January 2025). [CrossRef]

- McCombs, M. Setting the Agenda: The Mass Media and Public Opinion; Polity Press: Cambridge, UK, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Scheufele, D.A.; Tewksbury, D. Framing, agenda setting, and priming: The evolution of three media effects models. J. Commun. 2007, 57, 9–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shang, B.; Duan, Y.; Brehm, W.; Liang, W. Subjective theories of Chinese office workers with irregular physical activity: An interview-based study. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 854855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rey, G. El Cuerpo del Delito. Representación y Narrativas Mediáticas de la Seguridad Ciudadana; Centro de Competencia en Comunicación para América Latina: Bogotá, Colombia, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Castro-Carrasco, P.; Cuadra Martínez, D.; Gubbins, V.; Rodríguez-Pastene, F.; Carrasco Aguilar, C.; Caamaño-Vega, V.; Zelaya, M. Subjective theories of the Chilean teachers’ union about school climate and violence after the pandemic: A study of web news. Front. Educ. 2024, 9, 1455387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuentealba-Jorquera, D.; Rodríguez-Pastene-Vicencio, F.; Andrada, P.; Castro-Carrasco, P.; Caamaño-Vega, V.; Gubbins, V.; Zelaya, M. Teorías subjetivas sobre convivencia y violencia escolar en discurso experto en la prensa de 2022. Rev. Lat. Comun. Soc. 2025, 84, 1–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCombs, M. Influencia de las noticias sobre nuestras imágenes del mundo. In Los Efectos de los Medios de Comunicación: Investigaciones y Teorías; En Bryant, J., Zillmann, D., Eds.; Editorial Paidós: Barcelona, Spain, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Goffman, E. Frame Analysis: An Essay on the Organization of Experience; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1974. [Google Scholar]

- Carvajal, V.; Rodríguez-Alarcón, L.; Velasco, V. Siete Puntos Clave para Crear Nuevas Narrativas Sobre los Movimientos de las Personas en el Mundo. 2019. Available online: https://porcausa.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/05/porCausa_Nuevas_Narrativas_8_mayo_2019-1.pdf (accessed on 25 January 2025).

- Rodrigo-Alsina, M. La Construcción de la Noticia, 2nd ed.; Ediciones Paidós: Barcelona, Spain, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Saptaparna Nath, S.; Ashiqur Rahman, A. Social media’s agenda-setting role in Bangladesh’s July 2024 student movement. J. Gov. Secur. Dev. 2025, 6, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saez, V. La criminalización mediática en los discursos sobre la escuela argentina. Psicoperspectivas 2019, 18, 144–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agurto, R.; Araya, C.; Amaro, M.; Muñoz, P.; Mardones, F.Y.; Vidal, A. Weblogs y Cibermedios en Chile. Los Desafíos de un Formato en Evolución y Sus Usos en La Tercera, El Mercurio, La Cuarta y El Mostrador [en línea]; Universidad de Chile—Facultad de Comunicación e Imagen: Santiago, Chile, 2006; Available online: https://repositorio.uchile.cl/handle/2250/184234 (accessed on 25 January 2025).

- Asociación Técnica de Diarios Latinoamericanos. Sitio web de la ATDL. 2025. Available online: https://www.atdl.org/ (accessed on 25 January 2025).

- Martin-Neira, J.I.; Rojas-Torrijos, J.L. Periodismo deportivo con enfoque científico: Un estudio de caso a partir de la experiencia del diario LUN de Chile. Estud. Sobre Mensaje Periodístico 2024, 30, 885–895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niklander, S.; Pastene, F.R.; Mestrovic, D.; Senarega, H. Journalistic treatment of the tissue collusion in Chile: Comparative analysis between El Mercurio and El Mostrador. In Proceedings of the 2019 14th Iberian Conference on Information Systems and Technologies (CISTI), Coimbra, Portugal, 19–22 June 2019; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Rodríguez-Pastene, F.; Niklander, S.; Ojeda, G.; Vera, E. Interculturalidad y representación social: El conflicto de la Araucanía en la prensa chilena. Casos Melinao y Luchisnger. Estud. Sobre Mensaje Periodístico 2020, 26, 1583–1598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Couso, J. El Mercado Como Obstáculo a la Libertad de Expresión: La Concentración de la Prensa Escrita en Chile en la Era Democrática; Documento de Trabajo, 23; Plataforma Democrática: São Paulo, SP, Brasil, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Fundación La Fuente; IPSOS. Leer en Chile 2022: Estudio de Hábitos y Percepciones Lectoras. 2022. Available online: https://www.ipsos.com/sites/default/files/ct/publication/documents/2022-10/Leer%20en%20Chile%202022_baja.pdf (accessed on 24 January 2025).

- Feedback; Pontificia Universidad Católica de Valparaíso. Informe 2025: Consumo de Noticias y Evaluación del Periodismo en Chile. 2025. Available online: https://www.feedbackresearch.cl/consumo-noticias-2025 (accessed on 22 January 2025).

- Piñuel, J.L. Epistemología, metodología y técnicas del análisis de contenido. Estud. Sociolingüística 2002, 3, 1–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krippendorff, K. Metodología de Análisis de Contenido: Teoría y Práctica (L. Wolfson, Trad.); Ediciones Paidós: Mexico City, Mexico, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Castro-Carrasco, P.J.; Gubbins, V.; Caamaño, V.; González-Palta, I.; Rodríguez-Pastene Vicencio, F.; Zelaya, M.; Carrasco-Aguilar, C. Public Discourse of the Chilean Ministry of Education on School Violence and Convivencia Escolar: A Subjective Theories Approach. Soc. Sci. 2025, 14, 539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Pastene, F. Del Atributo a la Promesa. Representaciones del Consumo en INGLATERRA, 1881–1910. Un Estudio de la Publicidad como Fuente Historiográfica. Ph.D. Thesis, Pontificia Universidad Católica de Valparaíso, Valparaiso, Chile, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Espelage, D.; Sun, J.; Valido, A. Cyberbullying. In Handbook of Educational Psychology, 4th ed.; Schutz, P., Muis, K., Eds.; Routledge: Oxfordshire, UK, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Santana, A. Escuelas en Transformación: Programas de Intervención Social Como Apuestas de Mejoramiento Escolar en Contextos de Pobreza; Ediciones Universidad Alberto Hurtado: Santiago, Chile, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Molcho, M.; Walsh, S.D.; King, N.; Pickett, W.; Donnelly, P.D.; Cosma, A.; Elgar, F.J.; Ng, K.; Augustine, L.; Malinowska-Cieślik, M.; et al. Trends in indicators of violence among adolescents in Europe and North America, 1994–2022. Int. J. Public Health 2025, 70, 1607654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Worrell, F.; Astor, R.; Reddy, L.; Martinez, A.; Perry, A.; Anderman, E.; McMahon, S.; Espelage, D. Violence directed against teachers during the COVID-19 pandemic: A social-ecological analysis of safety and well-being. Sch. Psychol. 2023, 39, 510–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cornell, D.; Kerere, J.; Konold, T.; Maeng, J.; Afolabi, K.; Huang, F.; Cowley, D. Referral rates for school threat assessment. Psychol. Sch. 2025, 62, 1294–1305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scott, S.; Katsiyannis, A.; Rapa, L.; Durham, O. School shootings in the United States: 1997–2022. Pediatrics 2024, 15, e2023064311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Imran, M. Criminological examination of physical and psychological violence committed against children in the school environment. Riwayat Educ. J. Hist. Humanit. 2024, 7, 41–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canci, L.; Gassen, A.P.; da Rosa, S.A. School violence: Children and teachers in a socio-economic–political–ideological plot. Psicol. Esc. E Educ. 2023, 27, e256822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forsberg, J.T.; Thorvaldsen, S. The severe impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on bullying victimization, mental health indicators, and quality of life. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 22634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrades, J. “Convivencia escolar en Latinoamérica: Una revisión bibliográfica”. Rev. Electrónica Educ. 2020, 24, 346–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuadra, D.; Castro, P.J.; Tognetta, L.R.P.; Pérez, D.; Véliz, D.; y Menares, N. Teorías subjetivas de la convivencia escolar: ¿Qué dicen los padres? Psicol. Esc. Educ. 2021, 25, e221423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edling, S.; Liljestrand, J. Let’s talk about teacher education! Analysing the media debates in 2016-2017 on teacher education using Sweden as a case. Asia-Pac. J. Teach. Educ. 2019, 48, 251–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldstein, R.A. Imaging the Frame: Media Representations of Teachers, Their Unions, NCLB, and Education Reform. Educ. Policy 2011, 25, 543–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrer, A.F.; Retis, J. Hegemonía y resistencia en el espacio mediático: Los medios de minorías étnicas. In Comunicación y diversidad: Selección de comunicaciones del VII Congreso Internacional de la Asociación Española de Investigación de la Comunicación; Ediciones Profesionales de la Información SL: Granada, Spain, 2020; pp. 131–141. [Google Scholar]

- Kress, G. Multimodal discourse analysis. In The Routledge Handbook of Discourse Analysis, 2nd ed.; Handford, M., Gee, J.P., Eds.; Routledge: Oxfordshire, UK, 2023. [Google Scholar]

| HEADLINE: Name of the author of the news item, interview or report being analyzed. Completed. Open category. |

| MEDIUM: The publication platform or outlet of the news item, interview or report. Category closed. EL MOSTRADOR/SOYCHILE/LUN |

| DATE: The date on which the news item, interview or report was published. Completed. Open category. |

| CATEGORY: The general theme or subject addressed by the news item, interview or report. Closed category (obtained after analyzing the news). Not excluding (there may be more than one category per news item). AUTHORITY ROLE/FAMILY ROLE/TEACHERS’ ROLE/SAFETY AND ORDER/ISSUES/PANDEMIC |

| Authority role: Representatives or institutions linked to the executive, legislative, municipal, regional governments, etc. Family role: The role of family members, guardians and legal proxies in general. Teaching role: The work of educators in preventing and repairing harm. Order and Justice: Representatives or institutions linked to armed forces, and law enforcement, as well as the judiciary (prosecutors, judges, public defenders, etc.). Issues: Violence, bullying, school dropout rates, mental health, etc. |

| IMPLICIT/EXPLICIT: Indicates whether the subjective theory is presented denotatively (explicitly) or connotatively (implicitly) in the analyzed text. Category closed. |

| DIRECT QUOTATION: Passage or passages from the journalistic text—whether a news article, interview or report—that support the identified subjective theory. Completed. Open category. |

| SOURCE: Name and position of the individual or entity who expresses or supports the identified subjective theory. |

| SOURCE TYPE: The category or type of source that expresses or supports the identified subjective theory. Category closed. GOVERNMENT AUTHORITY/FAMILY/MEDIA/TEACHER/EXPERT/EDUCATIONAL INSTITUTION/LAW ENFORCEMENT AND ARMED FORCES/JUDICIARY/LEGISLATURE/TOWN COUNCIL |

| TYPE OF QUOTE: Classification or rating of the quote that supports the identified subjective theory. Category closed. DIRECT (QUOTATION IN QUOTATION MARKS, LITERAL)/INDIRECT (PARAPHRASED QUOTATION)/NEUTRAL (SUPPORTED BY THE MEDIA IN THE TEXT OF THE NEWS ARTICLE). |

| WHAT IT EXPLAINS: Indicates whether the subjective theory refers to the causes, intervening factors, strategies or consequences of the action. Category closed. CAUSE/EFFECT. |

| ACTION ORIENTATION: Indicates the intended purpose or guiding effect of the presented subjective theory. Category closed. INITIATES ACTION/PERPETUATES ACTION/INHIBITS ACTION. |

| NOTE: Notes from the researcher. Open category. Completed. |

| 1. MACRO-LEVEL AND MICRO-LEVEL STs |

| 1.1 Adults are responsible for the rise in school violence |

| 1.1.1 Violence can be explained by the tendency of children and adolescents to imitate the behavior of those around them. |

| 1.1.2 Violence can be explained by the failure of adults to set a positive example for children and adolescents. |

| 1.1.3 Society as a whole must take responsibility for the issue. |

| 1.2 The justice system plays a role in preventing violence. |

| 1.2.1 Justice that acts as a deterrent helps prevent new cases of violence. |

| 1.3 The rise in problems leads to protests. |

| 1.3.1 Guardians are taking action to raise awareness about the issue. |

| 1.3.2 Teachers are mobilizing because they are overwhelmed by violence. |

| 1.3.3 Students mobilize to raise awareness about the issue. |

| 1.4 Violence in Chile is a structural issue. |

| 1.5 The return to on-site classes leads to various problems, including violence, dropouts, bullying and mental health issues. |

| 1.5.1 Children and adolescents struggle with social interactions after the pandemic. |

| 1.5.2 Children and adolescents experience stress from the academic demands of on-site schooling. |

| 1.5.3 Children and adolescents were exposed to violent stimuli (e.g., video games, YouTube) during the pandemic and are replicating those behaviors. |

| 1.5.4 Children and adolescents did not receive mental health support during the pandemic. |

| 1.5.5 Children and adolescents experienced various readjustments and changes that acted as stressors. |

| 1.5.6 Children and adolescents dropped out of school due to their parents’ economic difficulties because they could no longer afford tuition or required their children to work. |

| 1.6 The role of education professionals can help prevent violence. |

| 1.6.1 Teacher training and a proactive approach help address the problem more effectively. |

| 1.6.2 Developing and implementing coexistence protocols can help prevent school violence. |

| 1.6.3 Hiring specialized professionals can help prevent violence. |

| 1.7 The problems stem from the negligence of the authorities. |

| 1.7.1 The ministry has failed to take adequate measures. |

| 1.7.2 The Education Superintendency has not implemented adequate measures. |

| 1.7.3 The Office of the Children’s Ombudsman has failed to take adequate measures. |

| 1.7.4 The local council is not taking adequate measures. |

| 1.8 Violence results from negligence on the part of educational institutions. |

| 1.8.1 Establishments do not have adequate protocols in place. |

| 1.8.2 Educational institutions fail to take action in response to reported incidents of violence and minimize their significance. |

| 1.8.3 Educational institutions do not act proactively to prevent. |

| 1.8.4 Educational institutions do not have trained personnel. |

| 1.8.5 Teachers are overworked and cannot deal with violence in the classroom. |

| 1.9. The role of authorities plays a part in preventing violence. |

| 1.9.1 The ministry has taken the appropriate measures. |

| 1.9.2 The Education Superintendency has not implemented adequate measures. |

| 1.9.3 The Office of the Children’s Ombudsman has taken appropriate measures. |

| 1.9.4 The local council is taking the appropriate measures. |

| 1.10. Initiatives from the private sector can help improve school coexistence. |

| 1.11. The development and promotion of specific activities can help enhance school coexistence. |

| 1.11.1 Regular physical activity improves the behavior and coexistence of children and adolescents. |

| 1.11.2 Opportunities for conversation and reflection enhance the behavior and coexistence of children and adolescents. |

| 1.12. Authorities’ role and the implementation of public policies can help improve school coexistence. |

| 1.13. The role of students prevents violence. |

| MARCH | JULY | NOVEMBER | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MACRO-LEVEL SUBJECTIVE THEORIES | TOTAL | SOY CHILE | EL MOSTRADOR | LUN | TOTAL | SOY CHILE | EL MOSTRADOR | LUN | TOTAL | SOY CHILE | EL MOSTRADOR | LUN | TOTAL |

| 1.1 Adults are responsible for the rise in school violence. | 4 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 6 | ||||

| 1.2 The justice system plays a role in preventing violence. | 5 | 3 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 3 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 9 | |||

| 1.3 The rise in problems leads to protests. | 5 | 1 | 1 | 3 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 7 | ||||

| 1.4 Violence in Chile is a structural issue. | 10 | 4 | 4 | 2 | 3 | 1 | 2 | 10 | 3 | 5 | 2 | 23 | |

| 1.5 The return to on-site classes leads to various problems, including violence, dropouts, bullying and mental health issues. | 9 | 4 | 4 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 10 | 2 | 7 | 1 | 21 | ||

| 1.6 The role of education professionals can help prevent violence. | 12 | 6 | 2 | 4 | 1 | 1 | 4 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 17 | ||

| 1.7 The problems stem from the negligence of the authorities. | 2 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 3 | 3 | 6 | ||||||

| 1.8 Violence results from negligence by educational institutions. | 3 | 2 | 1 | 3 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 7 | ||||

| 1.9 The role of authorities plays a part in preventing violence. | 7 | 1 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 1 | 4 | 3 | 1 | 14 | ||

| 1.10 Initiatives from the private sector can help improve school coexistence. | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 3 | ||||||

| 1.11 The development and promotion of specific activities can help enhance school coexistence. | 2 | 2 | 2 | ||||||||||

| 1.12 Authorities’ role and the implementation of public policies can help improve school coexistence. | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | ||||||||

| 1.13 The role of students prevents violence. | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 3 | |||||||

| TOTAL | 61 | 22 | 20 | 19 | 19 | 7 | 8 | 4 | 40 | 8 | 25 | 7 | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Rodríguez-Pastene, F.; Sorza, S.; Castro-Carrasco, P.J.; Carrasco-Aguilar, C.; Gubbins, V.; Caamaño-Vega, V.; Zelaya, M. Press and School Violence: Subjective Theories in the Post-Pandemic Narratives in Chilean Online Newspapers. COVID 2025, 5, 208. https://doi.org/10.3390/covid5120208

Rodríguez-Pastene F, Sorza S, Castro-Carrasco PJ, Carrasco-Aguilar C, Gubbins V, Caamaño-Vega V, Zelaya M. Press and School Violence: Subjective Theories in the Post-Pandemic Narratives in Chilean Online Newspapers. COVID. 2025; 5(12):208. https://doi.org/10.3390/covid5120208

Chicago/Turabian StyleRodríguez-Pastene, Fabiana, Sara Sorza, Pablo J. Castro-Carrasco, Claudia Carrasco-Aguilar, Verónica Gubbins, Vladimir Caamaño-Vega, and Martina Zelaya. 2025. "Press and School Violence: Subjective Theories in the Post-Pandemic Narratives in Chilean Online Newspapers" COVID 5, no. 12: 208. https://doi.org/10.3390/covid5120208

APA StyleRodríguez-Pastene, F., Sorza, S., Castro-Carrasco, P. J., Carrasco-Aguilar, C., Gubbins, V., Caamaño-Vega, V., & Zelaya, M. (2025). Press and School Violence: Subjective Theories in the Post-Pandemic Narratives in Chilean Online Newspapers. COVID, 5(12), 208. https://doi.org/10.3390/covid5120208