1. Introduction

1.1. Purpose of the Study

Long COVID, characterized by persistent symptoms lasting beyond the acute phase of the illness, presents a complex challenge to both patients and healthcare providers. Among these persistent symptoms, neurological manifestations such as anxiety and difficulty thinking clearly and concentrating have emerged as significant concerns. Despite increased recognition of the impact of long COVID on neurological functioning and mental health, there remains a significant gap in the literature regarding the nuanced interplay between these symptoms. More specifically, research indicates that individuals with long COVID frequently experience cognitive impairments and anxiety, but how these symptoms interact with one another remains underexplored.

1.2. Long COVID, Neurological Symptoms, and Anxiety

Long COVID is defined as COVID-19 symptoms persisting for more than 3 months, including, but not limited to, fatigue, anxiety, and cognitive deficits [

1,

2]. Research indicates that up to 50% of individuals recovering from COVID-19 develop persistent symptoms collectively termed long COVID [

3]. These symptoms include a wide range of physical and neuropsychiatric concerns [

4,

5].

For those living with long COVID, brain fog and difficulty with concentration have been reported with varying degrees of severity. Brain fog manifests as a state of mental cloudiness, characterized by reduced cognitive clarity, slower processing speed, and difficulty with tasks that require sustained mental effort. Research findings suggest that brain fog is one of the most reported symptoms of long COVID and is often associated with neuroinflammation and structural changes in the brain, such as those affecting white matter and the frontal cortex [

4,

6]. Concentration deficits manifest as difficulties in sustaining attention, completing tasks, and maintaining mental engagement during activities that typically require cognitive effort [

7]. Literature highlights that concentration difficulties are a significant and persistent symptom of long COVID, impacting a substantial portion of patients [

7,

8,

9]. Recent meta-analyses highlight that these cognitive impairments, such as brain fog and difficulty concentrating, are increasingly prevalent [

9,

10]. These symptoms can impact people’s sense of self, social interactions, work, and overall quality of life.

Persistent cognitive symptoms, such as brain fog and difficulty concentrating, can cause anxiety, making it challenging for individuals to focus on tasks and maintain mental clarity [

11]. Anxiety is one of the most persistent neuropsychiatric symptoms associated with long COVID, often continuing well beyond recovery from the acute phase of infection [

4,

12]. This anxiety is frequently attributed to uncertainty surrounding ongoing symptoms, fears of long-term health consequences, and the psychological distress experienced during the pandemic [

13,

14]. Evidence also suggests that anxiety is positively correlated with COVID-19 severity and the presence of other debilitating symptoms, causing both psychological and physical distress [

15]. Furthermore, anxiety is known to impact neurological systems, including areas of the brain responsible for cognitive functions such as concentration. For those living with long COVID, it is important to consider how cognitive impairments associated with the virus may impact anxiety, exacerbate symptoms, and adversely affect overall well-being.

Since there is a dearth of literature exploring the interplay between these variables, this study aims to provide a more nuanced understanding of the relationship between selective cognitive deficits and anxiety in individuals with long COVID, ultimately contributing to better clinical outcomes and targeted interventions for this population. The first hypothesis (H1) proposes that long COVID will be negatively associated with clarity of thought. The second hypothesis (H2) suggests that the association between long COVID and clarity of thought is mediated by anxiety. More specifically, it is expected that those with long COVID will be more anxious, which, in turn, makes it more difficult for them to think clearly. Participants with long COVID are expected to have more difficulty concentrating (H3) and to be more anxious, which in turn will exacerbate their difficulty with concentration (H4). Finally, participants with higher levels of anxiety are hypothesized to have lower clarity of thought (H5) and greater difficulty concentrating (H6). Nonetheless, given the cross-sectional design of the present study, potential mediation effects should be interpreted with caution, as causal inferences regarding temporal ordering cannot be firmly established.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Research

This study used archival data [

16] from the COVID-19 Health and Mental Health Survey [

17]. This study received ethical approval from the Fielding Graduate University Institutional Review Board (IRB No. 21-1101) for the research project titled “The association between emotional distress, personal characteristics, behaviors, relationships and health during the COVID-19 pandemic” (approved on 15 November 2021). Participants were recruited through the Qualtrics service and did not directly interact with the researcher. The survey was administered via Qualtrics. This survey sought to expand the understanding of the impact of COVID-19 on psychosocial functioning by examining the association between personal characteristics, emotional distress, behaviors, relationships, and health during the COVID-19 pandemic. There were 120 questions on the survey, including demographics, standardized questionnaires, and general questions on various topics.

2.2. Sample

Participants were required to be at least 18 years of age, living in the United States of America, and fluent in the English language. The data of participants who did not fully complete the survey were excluded. The inclusion and exclusion criteria were communicated to the participants before obtaining consent, ensuring transparency, safety, and adhering to ethical standards. If a participant was excluded from the study, they were made aware of it via Qualtrics.

Participants provided digital written informed consent prior to proceeding with the online survey. They were informed about the possibility of experiencing some emotional discomfort during or as a result of the study. Furthermore, information about referral information for individual and group support resources was included in the form. Before viewing the survey, participants were able to decline participation and were allowed to exit the study at any time.

The sample for this study comprised individuals who self-report experiencing long COVID symptoms (n = 97) as opposed to those who do not report such symptoms (n = 1823). To achieve a more balanced number of respondents in these groups, a random sample of 100 was extracted from the larger group of those without symptoms of long COVID. The final target sample included approximately 197 participants.

The independent variable was the presence or absence of long COVID symptoms. Participants were categorized into two groups: those who reported experiencing symptoms consistent with long COVID and those who do not report such symptoms. The dependent variables of interest were neurological symptoms including difficulties with thinking clearly (brain/mind fog) and concentrating.

Anxiety was examined as a mediator of these neurological symptoms among individuals with long COVID. The primary analysis examined the bivariate association between long COVID and neurological symptoms, providing insight into the direct relationship between these two variables, independent of other factors.

2.3. Measures/Instrumentation

The study examined several core variables, including long COVID, anxiety, difficulty thinking clearly, and difficulty concentrating. Long COVID is defined as the presence of COVID-19 symptoms for more than 3 months. This was measured using survey responses to questions regarding past COVID-19 infection and the duration of symptoms. Specifically, participants answered the question “Did you have COVID-19?”, with options being “Yes”, “No”, or “Uncertain”.

The dependent variables, difficulty thinking clearly and difficulty concentrating, were assessed with the question asking participants which symptoms or complications they were still experiencing. Response options for this study included “Difficulty thinking clearly (brain/mind fog)” and “Difficulty concentrating.” These data were also categorical.

The PROMIS

® Emotional Distress—Anxiety Short Form 4a is a four-item short version of the original 29-item PROMIS

® Item Bank Version 1.0—Emotional Distress—Anxiety questionnaire developed by [

18] Pilkonis et al. (2011). The short form 4a consists of four items designed to evaluate the frequency and intensity of anxiety symptoms including feelings of nervousness or worry, physical symptoms, cognitive experiences, and general levels of distress experienced by an individual in the past week. All items were rated using a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (never) to 5 (always). The PROMIS

® Anxiety Short Form 4a demonstrates strong psychometric properties. It has high internal consistency, with Cronbach’s alpha typically above 0.90, ensuring reliable assessment of anxiety [

19]). The scale shows robust test–retest reliability (0.80–0.90) and strong validity across multiple dimensions. It has strong convergent validity, correlating well with other anxiety measures, and discriminant validity, distinguishing anxiety from other constructs [

20]. Content validity is confirmed through expert review and item development, while construct validity is supported by correlations with established measures like the GAD-7 and HADS [

20]. In addition, criterion validity is demonstrated through relationships with depression and quality of life [

18]. Factorial validity, shown by factor analyses, confirms that the items load onto a single factor, validating the unidimensional nature of anxiety [

21]. In summary, the PROMIS

® Anxiety Short Form 4a is a reliable, valid, and comprehensive tool for assessing anxiety-related emotional distress and for screening anxiety disorders [

20].

In summary, long COVID was measured categorically based on the presence of chronic symptoms. Difficulty thinking clearly and difficulty concentrating was measured categorically, while anxiety was measured on a continuous scale using the PROMIS® scale. This approach facilitated a comprehensive analysis of the relationships between long COVID, anxiety, and cognitive symptoms (brain fog and concentration).

2.4. Statistical Analysis

Prior to analysis, all data were screened for missing cases and, where appropriate (PROMIS® Anxiety Scale), for distributional assumptions and outliers. Descriptive statistics were generated for all the core variables along with select demographic characteristics (gender, education level, and race).

The hypotheses were all tested with a combination of bivariate and multivariate logistic regression because the outcomes are categorical (dichotomous indicators of symptoms). The first and third hypotheses, respectively, addressed the association between long COVID and brain fog (difficulty thinking; H1) and difficulty concentrating (H3). The analyses pertaining to these hypotheses proceeded in two steps. In the first step, the bivariate (unadjusted) associations between long COVID and the symptoms were examined with chi-square. In a second step, hierarchical logistic regression models were run to examine the impact of long COVID on the outcomes beyond what can be explained by the demographic or other covariates in the model. The mediation hypotheses (H2 and H4) were tested with a logistic regression-based approach to mediation analysis using the PROCESS software developed by Hayes [

22]. With this approach, evidence of mediation takes the form of significant indirect effects as indicated by bias-corrected bootstrapped confidence intervals that exclude zero effect. Path diagrams depicting the association between long COVID, anxiety, and neurological symptoms were prepared.

3. Results

3.1. Sample Characteristics

Demographic characteristics were compared across the diagnostic groups (long COVID versus no long COVID). Results are presented in

Table 1. As seen in the table, no significant differences across the diagnostic groups were observed for either gender or level of education. However, the LC group had a significantly higher percentage of white participants (83.5%) than the comparison group (69.4%).

As indicated in

Table 2, the sample was disproportionately male (57.4%) and White/Caucasian (76.1%). With respect to education, over two-thirds of the sample (71.5%) reported at least some college or training beyond a high school degree.

3.2. Overall Rates of Long COVID and Neuro Symptoms

The outcome of interest concerned neurological symptoms. In the final sample, 31 (15.7%) reported difficulty thinking clearly, and 27 (13.7%) reported difficulty concentrating. A total of 36 respondents (18.3%) reported either of the two neurological symptoms. Of those with neurological symptoms, 14 (7.1%) reported one symptom, and 22 (11.2%) reported both symptoms.

3.3. Screening of Scaled Variables (Anxiety)

The anxiety measure was screened for distributional assumptions and outliers. The distribution was effectively normal, and no outliers were identified.

3.4. Bivariate Association Between Demographic Characteristics and Outcomes

Bivariate analyses were run to examine the association between select demographic characteristics (gender, race, and level of education) and the outcomes of interest (difficulty thinking clearly and difficulty concentrating) within the entire sample. No gender differences were found, and level of education was not associated with these neurological symptoms. A dichotomous indicator of race (White and non-White), however, was significantly associated with both symptoms. Specifically, White participants were significantly more likely to report difficulty thinking clearly (19.5%) than non-White participants (4.3%), χ2 (1) = 6.01, p = 0.014, odds ratio = 5.32 (1.22, 23.22). The odds ratio indicated that White respondents were more than five times as likely to report difficulty thinking clearly. White participants were also significantly more likely to report difficulty concentrating (16.8%) than non-White participants (4.3%), χ2 (1) = 4.55, p = 0.033, odds ratio = 4.44 (1.01, 19.50). Considering this finding, race served as covariate in subsequent analyses.

3.5. Tests of Hypotheses

H1. Association Between Long Covid and Neuro Symptoms.

To examine the association between long COVID and neurological symptoms (difficulty thinking clearly and difficulty concentrating), the analysis proceeded in two steps. In the first step, the bivariate (unadjusted) association between long COVID and these symptoms was examined (see

Table 3 for results). As seen in the table, there was a strong, significant association between long COVID and both difficulty thinking clearly and difficulty concentrating.

The association between long COVID and these neurological symptoms was further examined with hierarchical logistic regression models to determine whether long COVID predicted the symptoms beyond what could be explained by the demographic covariate (race). In the first model tested, results indicated that long COVID predicted difficulty thinking clearly, χ

2 (1) = 24.72,

p < 0.001, in this case, beyond what could be explained by race. In the final adjusted model, the odds ratio for long COVID status (0 = no, 1 = yes) was 11.84 (3.44, 40.78) indicating that those with long COVID were approximately 11 times more likely to report difficulty thinking clearly than those who did not have long COVID (see

Table 4). Results pertaining to the model predicting difficulty concentrating can be found in

Table 5. As with the first neurological symptom, long COVID also predicted difficulty concentrating in the adjusted model, χ

2 (1) = 24.32,

p < 0.001. The odds ratio for long COVID, 15.43 (3.52, 67.57), indicated that respondents with long COVID were 15 times more likely to report difficulty concentrating than those without long COVID. Once again, race was not a significant predictor of this symptom in this adjusted model.

3.6. Does Anxiety Mediate the Association Between Long COVID and Neuro Symptoms?

To test the hypothesis that anxiety mediated the association between long COVID and neurological symptoms, two models were analyzed with a regression-based approach to mediation analysis using the PROCESS software developed by Hayes [

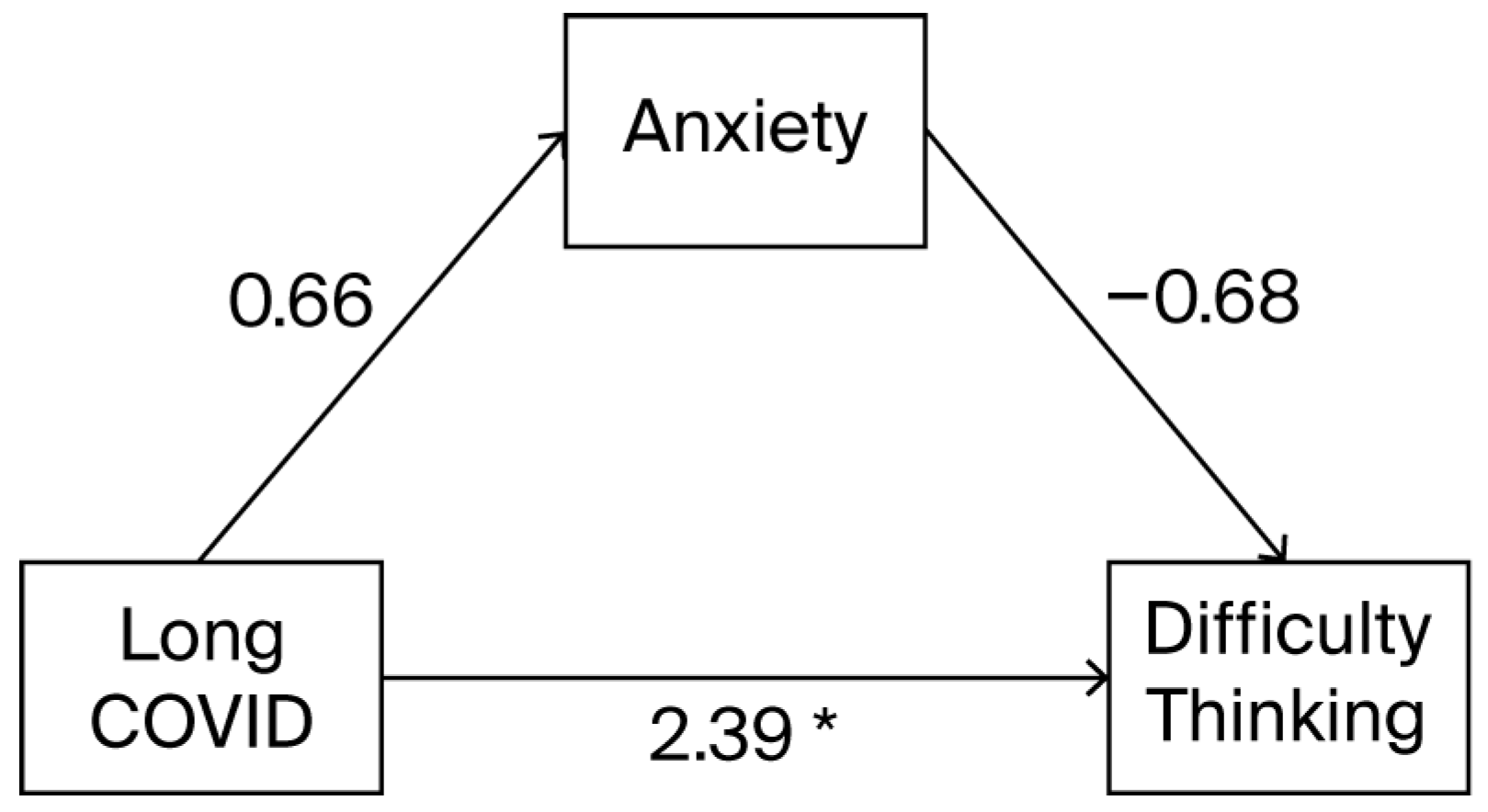

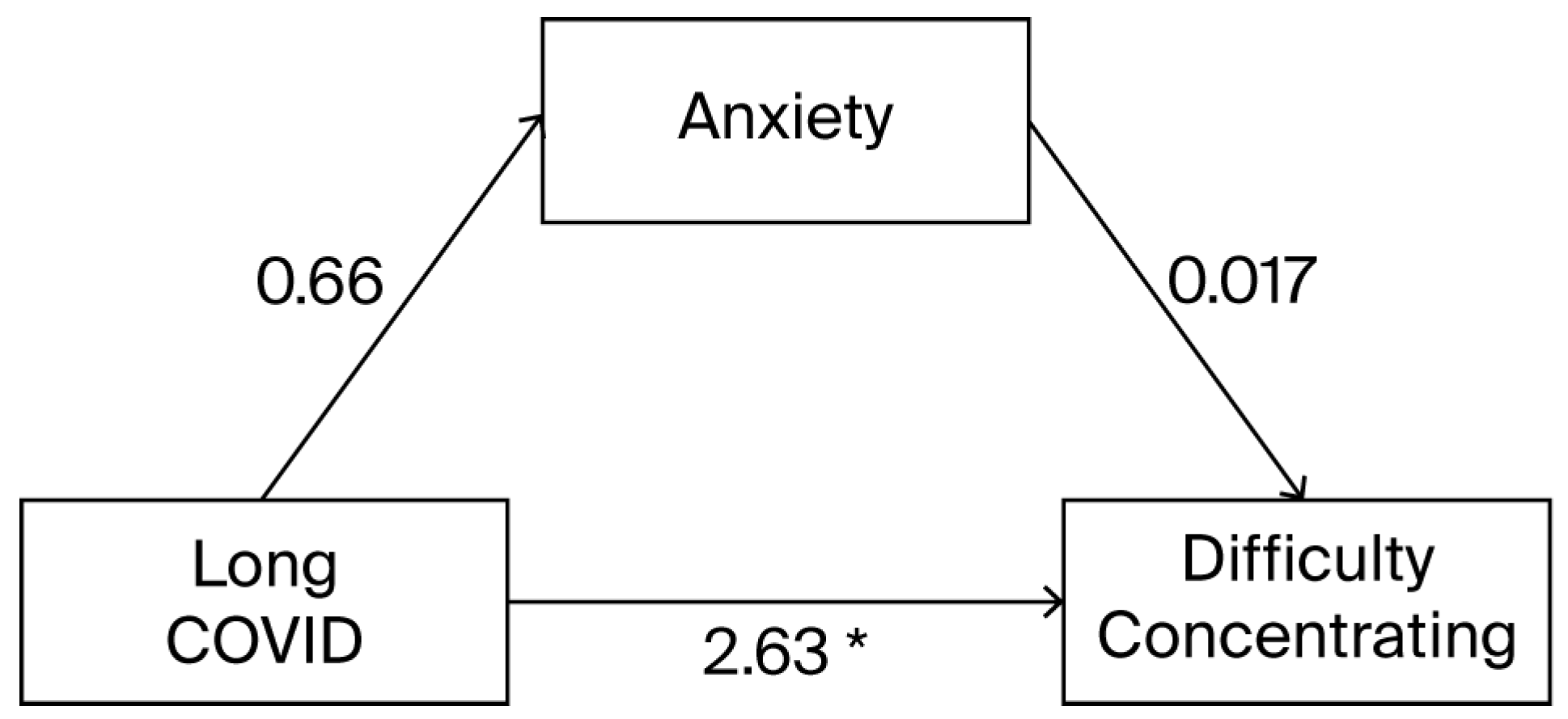

22]). Evidence of mediation was indicated by a significant indirect effect (i.e., long COVID → anxiety → neurological symptoms). Bias-corrected bootstrapped confidence intervals were used to determine the significance of the indirect effect. Path diagrams illustrating the mediation models are shown in

Figure 1 and

Figure 2.

Figure 1 depicts the relationship between long COVID and difficulty thinking clearly as mediated by anxiety. For the model predicting difficulty thinking clearly, there was no evidence that the effect of long COVID was mediated by anxiety, B = −0.045 (−0.22, 0.08). However, as shown in

Figure 1, there was a significant direct (unmediated) effect of long COVID.

Figure 2 depicts the relationship between long COVID and difficulty concentrating as mediated by anxiety. Similarly, for the model predicting difficulty concentrating, the indirect effect of long COVID was also not significant, B = 0.011 (−0.14, 0.16). As shown in

Figure 2, there was a direct effect of long COVID on difficulty concentrating.

Figure 2 depicts the relationship between long COVID and difficulty concentrating as mediated by anxiety. Similarly, for the model predicting difficulty concentrating, the indirect effect of long COVID was also not significant, B = 0.011 (−0.14, 0.16). As shown in

Figure 2, long COVID had a direct effect on difficulty concentrating.

4. Discussion

The purpose of this study was to investigate the relationships between the presence of long COVID, neurological impairments (brain fog and concentration), and anxiety. The findings of this study confirm that there is a significant relationship between those who have long COVID and the presence of respective neurological symptoms, including difficulty thinking clearly (brain/mind fog) and difficulty concentrating. This result aligns with existing literature that points to neurological manifestations of long COVID, including impairments such as brain fog and difficulty with concentrating [

13]. Neurological deficits are becoming increasingly recognized as part of the post-acute phase of COVID-19, with studies indicating that a significant proportion of patients experience cognitive dysfunction months after recovery from the acute infection [

15]. These results highlight the long-term neurological impact of COVID-19, further supporting the notion that long COVID is not simply a respiratory illness, but also a multi-system condition with potential significant adverse effects on brain function. These findings contribute to the growing body of literature emphasizing the need for neuropsychological screening of those diagnosed with long COVID and for targeted interventions to address neurological impairments in long COVID patients.

The findings of this study also elucidate those individuals with long COVID reporting significantly higher levels of anxiety compared to those without the condition, which is consistent with existing research highlighting the emotional consequences associated with long COVID [

3,

9,

10,

11]. The increased levels of anxiety observed in the long COVID group purport the growing recognition that post-viral conditions often have neuropsychiatric consequences, including heightened anxiety [

3]. Of relevance is that the mediation effect of anxiety on the relationship between long COVID and cognitive difficulties was not supported by the data. This finding is somewhat surprising, as anxiety is commonly associated with cognitive difficulties, particularly in the context of chronic illness [

3]. However, interestingly, anxiety is often associated with subjective cognitive concerns without objective cognitive impairment, which may explain what was found in the results [

23,

24]. Our findings bolster the notion that subjective cognitive concerns may reflect anxiety-related distress without objective cognitive impairment. However, it should be acknowledged that anxiety can be caused by long COVID or co-occur as a comorbid condition. This finding does not preclude whether anxiety exacerbates cognitive concerns in long COVID patients. This lack of mediation does, however, highlight the complex nature of neurological concerns in long COVID, where factors other than anxiety, such as direct neurological damage or lingering neuroinflammation, may play a more central role in impairing cognitive functioning.

4.1. Clinical Implications

Individuals with long COVID may experience a substantial reduction in quality of life due to persistent cognitive challenges such as difficulty thinking clearly and concentrating [

11]. This cognitive dysfunction can interfere with everyday tasks, work, and relationships, culminating in frustration, isolation, and anxiety. Public education on long COVID, the potential consequent neurological and psychological symptoms, and treatment options can assist those struggling with this chronic condition to proactively seek medical, psychological, and social intervention. This increased awareness may also reduce the stigma associated with these cognitive and psychological symptoms and foster a sense of compassion towards those struggling with long COVID.

As indicated above, the results indicate that individuals with long COVID can experience co-occurring subjective measures of neurological impairments and anxiety, factors that likely exacerbate one another. From a clinical perspective, this finding emphasizes the importance of healthcare providers recognizing the cognitive and neuropsychiatric symptoms of long COVID. It is important to routinely ask patients whether they are experiencing ongoing subjective neurological and psychiatric symptoms following a COVID-19 infection and then follow up with objective neuropsychological data collection to confirm the presence of neurocognitive deficits. Routine screening for cognitive deficits and mental health, including anxiety, should become part of standard clinical practice for individuals presenting with long COVID symptoms, offering patients quicker intervention that may lead to better biopsychosocial outcomes.

A crucial aspect of clinical practice is providing psychoeducation about the interplay between cognitive difficulties and anxiety. Many individuals with long COVID may not be aware that their anxiety could be exacerbating cognitive difficulties or, conversely, that cognitive impairments may be increasing their anxiety levels. Educating patients about how these factors influence one another can help them understand their symptoms better and reduce the distress associated with both. Incorporating psychoeducation into patient care can also provide individuals with strategies to cope with both cognitive challenges and anxiety. For example, teaching patients techniques to manage anxiety might improve their concentration, and improving cognitive performance could, in turn, attenuate anxiety. Ensuring that patients and their caregivers know how to recognize these patterns can empower them with practical tools for navigating their recovery. In addition, understanding options for cognitive rehabilitation, biofeedback (e.g., capnometry), and compensatory strategies may empower those living with long COVID to be more compliant with treatment recommendations and to be responsive to self-management in their treatment process.

Given the complex and varied nature of long COVID symptoms, clinicians should also consider making appropriate referrals to multidisciplinary professionals, including neurologists, psychologists, and rehabilitation specialists. Customized interventions are crucial for addressing the unique needs of each patient. While cognitive rehabilitation programs may be beneficial for those experiencing significant cognitive impairments, psychological interventions such as cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) or acceptance and commitment therapy (ACT) could help address anxiety and other emotional difficulties. Cognitive and emotional interventions should be tailored to the specific challenges that each individual with long COVID is facing. By offering personalized care plans, clinicians can improve treatment results and enhance their quality of life during recovery.

CBT is beneficial for individuals with long COVID who experience both anxiety and cognitive difficulties. The model of anxiety in CBT focuses on the interplay between thoughts, emotions, and behaviors and can assist individuals in better managing both their anxiety and cognitive symptoms. CBT techniques that target thought patterns contributing to anxiety can also improve attention and concentration by reducing cognitive distractions associated with anxious thoughts. Integrating CBT into the treatment plan for individuals with long COVID may help reduce anxiety levels and thereby improve cognitive functioning. Clinicians can incorporate CBT-based strategies into their practice by providing therapy directly to the patient or by referring the patients to a CBT-trained professional. In addition, providing the patient with basic cognitive rehabilitation exercises to assist with concentration or brain fog may decrease anxiety. Gently addressing cognitive and emotional concerns concurrently may assist in breaking the cycle of anxiety and cognitive deficits exacerbating one another.

4.2. Limitations and Recommendations for Future Research

The findings of this study provide valuable insights into cognitive and psychological impacts of long COVID, but they also point to important questions that remain unanswered. For instance, while anxiety does appear to co-occur with long COVID, it does not explain the cognitive difficulties experienced by patients. Future research could also explore alternative mediators, such as inflammation and other neurobiological factors, that better account for the relationship between long COVID and neurological impairments. Additionally, the role of anxiety in long COVID warrants further investigation. A pertinent question to explore is whether the duration and severity of anxiety impact cognitive functioning in those living with long COVID. Further, this study investigated subjective, self-reported cognitive concerns. An important follow-up study would explore the relationship between long COVID, psychosocial determinants, and anxiety on objective neurocognitive performance as quantified using neuropsychological testing of cognitive skills. Finally, given the significant levels of anxiety observed in this population, clinicians should consider the efficacy of mental health interventions as part of the comprehensive care for long COVID patients.

5. Conclusions

The results of this study imply that recovery from long COVID may need to be approached from an integrated perspective, incorporating both psychological and neurological treatment modalities. The intersection of cognitive dysfunction and anxiety complicates the recovery process, suggesting that interventions aimed at improving one aspect, whether cognitive function or mental health, may benefit from addressing both areas simultaneously. Thus, long COVID interventions should incorporate cognitive rehabilitation and psychological treatment to enhance overall recovery. Additionally, the recognition that anxiety does not mediate subjective cognitive difficulties but rather coexists with them emphasizes the importance of considering these as separate but interrelated domains of care. This dual approach, focusing on cognitive and emotional well-being, is essential for comprehensive long COVID management. Clinicians should adopt a holistic and individualized care model that accounts for the condition’s neurological and psychological dimensions.

The implications of this study are widespread, for society, individuals affected by long COVID, and for the clinicians who care for them. With increased awareness and targeted interventions, individuals with long COVID can receive more timely and effective treatment that addresses the full spectrum of their symptoms. Ultimately, these efforts can help improve the quality of life and promote more successful recovery trajectories for those struggling with the persistent effects of long COVID.

As the understanding of long COVID-19 evolves, it becomes increasingly clear that this chronic medical condition poses a substantial public health concern [

25]. Further research is necessary to understand its pervasive biopsychosocial presentation and the potential adverse consequences on physical and mental health, employment, education, psychosocial functioning, quality of life, and the healthcare system. Informed assessment and individualized intervention protocols should be developed to support the increasing number of people affected by long COVID.