Abstract

We set out to determine the impact of delirium and COVID-19 on length of stay and mortality. For this study, we conducted a retrospective cohort study of patients aged >65 years admitted to the Owensboro Health Regional Hospital between August 2021 and December 2023. Delirium was determined based on a score of ≥2 on the Nurse Delirium Screening Scale (NuDESC) recorded on all admitted patients three times a day during nursing shift change. Multivariate logistic regression models were used to evaluate the association between delirium, COVID-19, or both on 30-day, 60-day, 90-day, 180-day, 360-day mortality, adjusting for age, sex, race, smoking status, diabetes, hypertension, dementia, COPD, obesity, heart failure, and heart disease. A total of 4872 hospitalized patients were included in the study. Of these, 698 (14.3%) were identified as having delirium and 4174 (85.7%) as without delirium. Patients with delirium were slightly older than those without (79.5 ± 8.6 years old vs. 77.0 ± 7.9). After adjusting for comorbidities, delirium was associated with an increase of 3.3 hospitalization days (8.6 ± 9.6 days vs. 5.3 ± 5.6 p < 0.01). Delirium was associated with higher 30-day, 60-day, 90-day, 180-day, and 360-day mortality rates. COVID-19-positive patients with delirium had 717% higher odds of 30-day mortality compared to the COVID-19-negative patients without delirium (aOR 8.17 95% CL 4.60–14.3).

1. Introduction

COVID-19 is a complex infection that can have a dramatic effect on multiple organ systems, particularly in hospitalized patients. Studies have demonstrated that immunologic dysregulation [1,2], inflammation [3,4], vascular dysfunction [5], and other pathological mechanisms can occur during the acute phase. Owing to these mechanisms, COVID-19 has been shown to increase the risk of stroke, altered mental status, and other neurological manifestations in older adults [6]. In addition to these neurological conditions, delirium has been identified as a possible presenting symptom of COVID-19 [7].

Delirium is a complex geriatric syndrome whose pathophysiology in older adults can be multifactorial [8]. Systemic inflammation has been associated with delirium and progression to dementia [9,10]. Inflammatory and vascular dysfunctions often encountered during the acute infectious process of COVID-19 may contribute to the development of delirium. Delirium, which develops in the context of COVID-19, has been associated with higher disability and cognitive impairment [11]. Although delirium has historically been associated with an increased risk of mortality [12,13], a growing body of literature is recognizing the impact of delirium in the setting of COVID-19 [14].

Given these poor outcomes and risks to patients, research has supported the need for improved diagnosis and treatment of delirium [15]. Despite these concerns, delirium is often underdiagnosed among older hospitalized adults [16], and multiple barriers remain in the implementation of screening programs [17].

Our study aimed to determine the impact of delirium and COVID-19 on mortality in hospitalized older adults for up to one year after discharge. We hypothesized that given the robust inflammatory changes that occur during the acute infectious process of COVID-19, COVID-19-related delirium would be associated with a higher risk of mortality than delirium unrelated to COVID-19 infection. Furthermore, we postulate that the mortality risk associated with COVID-19-related delirium is higher than that of patients who develop COVID-19 without subsequent delirium.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Delirium Screening and Determination

The Owensboro Health Regional Hospital and the University of Louisville implemented the Inpatient Delirium Reduction and Early Acute Management (iDREAM) Process Improvement Initiative in 2021. The Nursing Delirium Screening Scale (NuDESC) was selected as the delirium screening tool to be completed by nursing staff every shift for all patients over 65 years of age admitted to the hospital. Nursing staff were trained to administer the scale, and the results were logged into the EPIC electronic medical record [18]. Scores were collected daily for each shift change for all patients admitted to the hospital. A score of 2 or more was considered positive for delirium

2.2. Statistical Analysis

We conducted a retrospective cohort study of patients aged >65 years admitted to the Owensboro Health Regional Hospital between August 2021 and December 2023. Delirium was determined based on a score of ≥2 on the Nurse Delirium Screening Scale (NuDESC) recorded on all admitted patients three times a day during nursing shift change. Testing by the NuDESC was recorded for changes occurring during that nursing shift for each of the three shifts. A positive screen at any point during the day was considered positive for that day. Continuous variables are presented as mean ± standard deviation and categorical variables as frequencies and percentages. Multivariate logistic regression models were used to evaluate the association between delirium, COVID-19, or both and 30-day, 60-day, 90-day, 180-day, 360-day mortality, adjusting for age, sex, race, smoking status, diabetes, hypertension, dementia, COPD, obesity, heart failure, and heart disease, compared to those who had neither delirium nor COVID-19. Multivariable linear regression was used to evaluate the association between delirium and the length of hospital stay. Statistical analysis was performed using R (R version 4.0.5).

2.3. Primary Outcomes

The primary outcomes of the study were mortality as a binary variable at 30, 60, 90, 180, and 360 days for each group of patients with and without COVID-19 or delirium and length of stay.

3. Results

3.1. Baseline Characteristics

A total of 4872 hospitalized patients were included in the study: 3926 (80.6%) were negative for both delirium and COVID-19, 248 (5.1%) had COVID-19 but not delirium, 634 (13.0%) had delirium in COVID-19-negative patients, and 64 (1.3%) had both delirium and COVID-19. Patients with both delirium and COVID-19 were slightly older than those without either (79.9 ± 8.7 years old vs. 77.0 ± 7.9). 2325 (47.7%) of all the patients were male. Most patients were white or Caucasian (4700, 96.5%). Regarding comorbidities, the four groups were comparable in terms of obesity, diabetes, hypertension, COPD, and heart disease. Patients with delirium had a higher rate of dementia (44, 6.9% in COVID-19-negative patients; 4, 6.2% in COVID-19-positive patients) compared to patients without delirium (70, 1.8% in COVID-19-negative patients, 2, 0.8% in COVID-19-positive patients) (p < 0.001).

The patients in the delirium group had a longer length of stay compared to the non-delirium group (11.6 ± 9.3 in COVID-19-positive patients and 8.6 ± 9.6 in COVID-19-negative patients vs. 5.8 ± 5.9 days in COVID-19-positive patients and 5.3 ± 5.1 in COVID-19-negative patients). The 30-day, 60-day, 90-day, 6-month, one-year mortality rates were the highest in the COVID-19-positive patients with delirium compared to those without delirium (Table 1).

Table 1.

Characteristics of Patients with and without Delirium by COVID-19 status. Delirium (+) means the patient was positive for delirium. Delirium (−) means they were delirium-negative during their hospital stay. COVID-19 (+) means the patient was COVID-19-positive. COVID-19 (−) means they were negative for COVID-19.

3.2. Higher Delirium Rates in COVID-19 Patients

A total of 312 (6.4%) patients tested positive for COVID-19 upon admission or discharge. Among the COVID-19-positive patients, 64 (20.5%) patients had delirium, a higher rate than those without COVID-19 (634, 13.9%, p = 0.002).

3.3. Association of Delirium with Mortality

After adjusting for age, gender, race, smoking status, diabetes, hypertension, dementia, COPD, obesity, heart disease and heart failure, having delirium was associated with 286% increase in the odds of death within 30 days of hospitalization (aOR = 3.86, 95% CI: 3.01–4.94), 213% increase in the odds of death within 60 days of hospitalization (aOR = 3.13, 95% CI: 2.49–3.93), 211% increase in the odds of death within 90 days of hospitalization (aOR = 3.11, 95% CI: 2.49–3.87), 199% increase in the odds of death within 180 days of hospitalization (aOR = 2.99, 95% CI: 2.43–3.68) and 165% increase in the odds of death within 360 days of hospitalization (aOR = 2.65, 95% CI: 2.16–3.24) (Table 2).

Table 2.

Adjusted Odds Ratio (aOR) for Patients with COVID-19 or Delirium. Delirium (+) means the patient was positive for delirium. Delirium (−) means they were delirium-negative during their hospital stay. COVID-19 (+) means the patient was COVID-19-positive. COVID-19 (−) means they were negative for COVID-19. aOR means adjusted odds ratio.

3.4. Association of Delirium with Length of Stay

After adjusting for age, sex, race, smoking status, diabetes, hypertension, dementia, COPD, obesity, heart disease, and heart failure, delirium was associated with an increase of 3.3 days, while delirium in the setting of COVID-19 was associated with an increase in length of stay of 6.3 days compared to non-delirium, non-COVID-19 patients (p < 0.001) (Table 3).

Table 3.

Length of stay by COVID and Delirium status. Delirium (+) means the patient was positive for delirium. Delirium (−) means they were delirium-negative during their hospital stay. COVID-19 (+) means the patient was COVID-19-positive. COVID-19 (−) means they were negative for COVID-19.

3.5. Association of COVID-19 and Delirium with Mortality

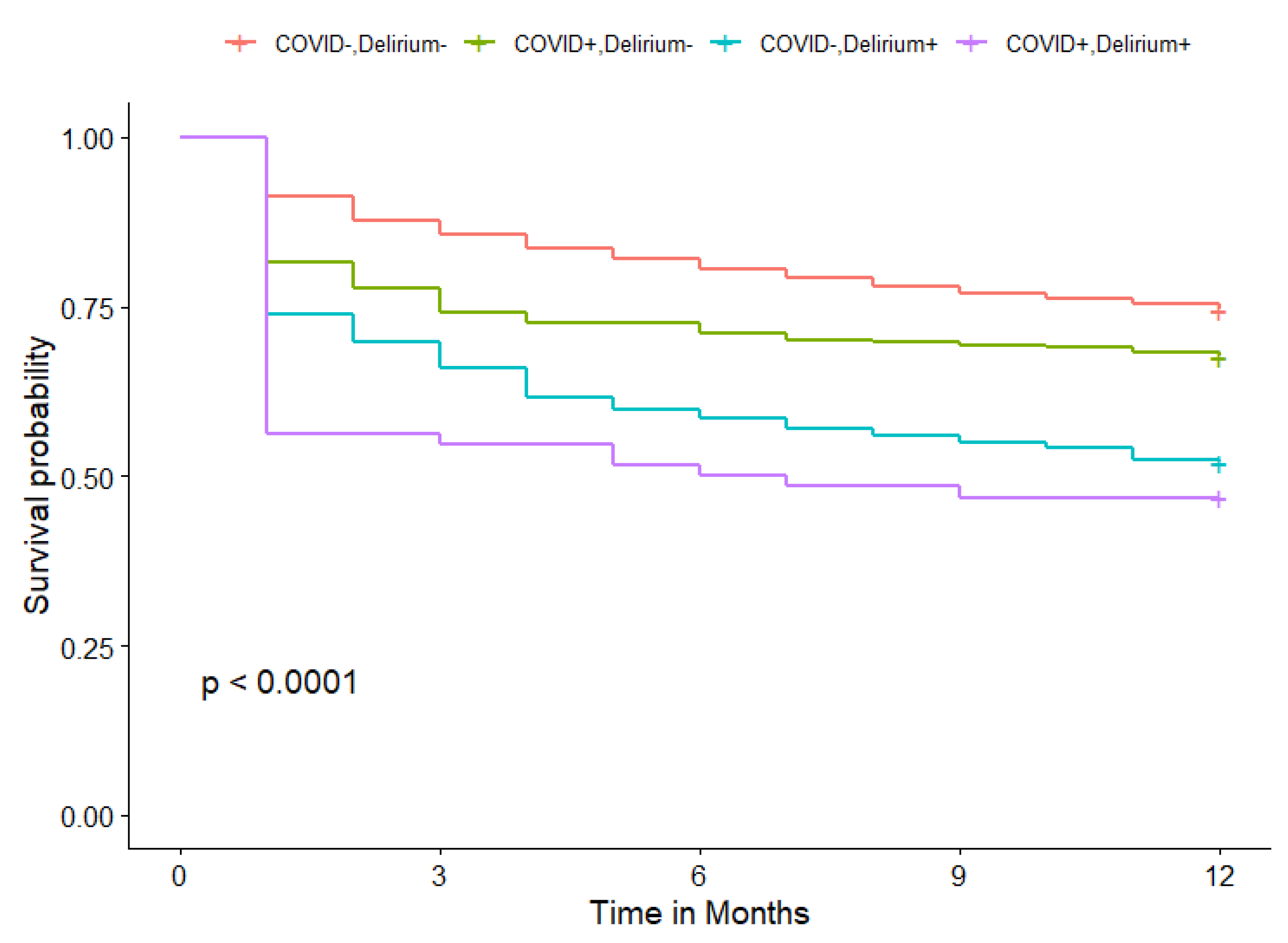

The 30-day mortality rate for COVID-19-positive patients with delirium was 43.8% (28 out of 64), 717% higher odds compared to our reference group, the COVID-19-negative patients without delirium, (aOR = 8.17, 95% CI: 4.60–14.3). (Table 2) The comparison of the survival curves for patients without delirium or COVID-19 to patients with COVID-19 but no delirium, patients with delirium but no COVID-19, and patients with delirium and COVID-19 is shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Survival plot comparing patients with COVID-19 infection, delirium, both COVID-19 infection and delirium, and without COVID-19 or delirium, showing p-value for the log-rank test. Notice that we treated death as happened at the end of each time frame (1, 2, 3, 6, 12 months) as the exact date of the death was unknown.

4. Discussion

4.1. Effects of COVID-19 and Delirium on Mortality

Our study attempted to understand the relationship between delirium and COVID-19 on mortality and length of stay. Our results show that patients who tested positive for COVID-19 and subsequently developed delirium had an increased risk of mortality at 30 days compared to those who were delirium-negative and COVID-19-positive. Patients who had delirium and COVID-19 tended to have increased mortality compared to delirium-positive COVID-19-negative patients. However, this data did not reach statistical significance.

The risk of mortality remained elevated for over one year without returning to a baseline rate compared to patients admitted to the hospital without delirium or COVID-19. By the one-year mark, delirium was associated with higher odds of mortality compared to having COVID-19 alone without delirium. These findings show how delirium is associated with mortality in both COVID-19 and non-COVID-19 patients while also carrying a higher one-year mortality than COVID-19 alone.

COVID-19 disproportionately affects older adults, with which is associated with an increased risk of mortality [19]. During the first year of the pandemic, over 81% of deaths occurred among adults aged >65 [20]. However, by one year after discharge, patients who had delirium and COVID-19 had a cumulative mortality of 53.1% compared to delirium-positive patients without COVID-19 (47.9%) and COVID-19-positive patients without delirium (32.3%). These findings further show that although COVID-19 is associated with increased mortality in older adults, the additional presence of delirium further effects this mortality risk (Figure 1).

Prior research has demonstrated that delirium is independently associated with an increase in one-year mortality [21,22]. Our study confirms these findings. Even when taking into consideration frailty, delirium remains a significant risk factor for mortality [23]. Our findings of increased mortality in the setting of COVID-19-related delirium support the need for hospital systems to adopt proactive measures to identify individuals with delirium, particularly those who are COVID-19-positive.

4.2. Effects of COVID-19 and Delirium on Length of Stay

Patients who developed delirium had a significantly longer length of stay than those without delirium. These findings are consistent with other studies that have demonstrated that patients who develop delirium have an increased length of stay [24,25]. Surprisingly, COVID-19-positive patients without delirium had less than a half day longer length of stay than COVID-19-negative patients without delirium. These findings may be secondary to the development of new treatments and clinical practices for COVID-19 [26]. The impact of delirium again represents a significant factor in the length of stay for older adults, adding an additional three–six days based on COVID-19 status. These findings further support the need for robust measures to address and identify delirium in inpatient settings.

4.3. Strengths and Limitations

One of the strengths of this study relates to the methods used to determine delirium. The hospital system invested heavily in creating a high-quality culture that promoted delirium screening and awareness. The nursing staff was trained to recognize delirium and use the NuDESC screening tool for each shift. All the patients admitted to the hospital during this period were screened daily using this method. Therefore, we could determine whether patients had developed delirium without relying on the ICD-10 codes or discharge summaries. Delirium has historically been underreported in medical discharge summaries and is not adequately screened during hospitalization due to various factors [27,28]. Owing to these policies, our study was capable of identifying delirium-positive patients with greater sensitivity. Another strength of this study was the implementation of delirium rounding by the hospital administration. High-risk patients and those with delirium were proactively rounded upon by an interdisciplinary team from the quality department, pharmacy, nutrition, physical therapy, nursing staff, and physicians. These daily team rounds conducted throughout the hospital helped reinforce delirium screening, identification of at-risk patients, and utilization of resources to support patients. These methods also helped to act as quality control methods to ensure that the screening protocols were maintained after the initial rollout and training. Due to proactive screening and intervention protocols, the length of stay and mortality rate associated with delirium may have been lower than the typical rates seen in other inpatient units. The limitations of the study include its retrospective nature. Although attempts were made to address potential confounding variables and comorbidities, other factors may have led to a higher mortality risk in these patients, which our study design could not adequately control for. Additionally, the number of patients who experienced delirium due to COVID-19 was relatively small compared to the total number of patients admitted to the hospital. Because of this smaller sample size, other confounding factors may have played a stronger role in the mortality and length of stay outcomes, which could not be fully accounted for in our design. Despite these statistical limitations, our data showed a clear trend toward increasing mortality, which could be detected by further higher-powered studies.

Patients admitted to the hospital with a COVID-19 diagnosis were presumed to have COVID-19 on arrival, with subsequent development of delirium or no delirium. There may be a small percentage of patients who were admitted without COVID-19 and then subsequently developed it during their hospital stay. As a result, our study may overestimate the mortality of patients with COVID-19 and delirium. Death was treated as a binary event without a specific time point. Due to this limitation, we are unable to determine if inpatient mortality occurred before an opportunity to develop delirium. Screening for delirium was performed on admission and during their entire hospital stay. If patients died due to illness severity before developing delirium, they were treated as non-delirium-related mortality. It is uncertain if they had lived longer, if they would have developed delirium because of the complex relationship between delirium and illness severity, and a lack of a recognized predictive model to estimate those outcomes. We were not able to determine illness severity on arrival, such as oxygen support or mechanical ventilation requirements. These confounding variables may have influenced mortality and delirium development.

Our study did not consider vaccination status, COVID-19 variants or changes in clinical treatment practices during the study period. These factors may have influenced later mortality risk. This study was conducted in a rural regional hospital in Western Kentucky with a predominantly Caucasian population. These findings may not apply to other regions or demographic populations. Lastly, due to the retrospective design, we were unable to determine which patients may have been initially infected or reinfected with COVID-19. The effect of reinfection on the development of delirium and other complications remains an active area of investigation.

5. Conclusions

COVID-19-related delirium is associated with increased mortality within the initial 30 days after discharge compared with non-COVID-19-related delirium and persists for up to one year. Further research is needed to understand the mechanisms underlying this increased risk.

Author Contributions

Project conceptualization and design: J.B. and F.T.; Methodology: J.B. and F.T.; Data curation: D.C. and B.B.; Formal analysis: F.T.; Investigation: D.C. and B.B.; Writing—original draft: J.B. and F.T.; Reviewing and editing: J.B., F.T., I.H., J.N., Z.P. and D.C.; Supervision and project administration: D.C., B.B. and I.H. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Institutional Review Board of the University of Louisville (Reference no. 780477, IRB no. 24.0214 on 22 March 2024).

Informed Consent Statement

This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the University of Louisville (Reference no. 780477, IRB no. 24.0214 on 22 March 2024) and exempted from the requirement for informed consent.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets presented in this article are not readily available because of Owensboro Health Regional Hospital data policies. Requests to access the datasets should be directed to Alice Bruce, the Owensboro Health Regional Hospital research compliance manager (alice.bruce@owensborohealth.org).

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge the staff of Owensboro Health Regional Hospital for their efforts to improve delirium care through several quality improvement initiatives, which made this study possible.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Mohandas, S.; Jagannathan, P.; Henrich, T.J.; Sherif, Z.A.; Bime, C.; Quinlan, E.; Portman, M.A.; Gennaro, M.; Rehman, J.; RECOVER Mechanistic Pathways Task Force. Immune mechanisms underlying COVID-19 pathology and post-acute sequelae of SARS-CoV-2 infection (PASC). eLife 2023, 12, e86014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davitt, E.; Davitt, C.; Mazer, M.B.; Areti, S.S.; Hotchkiss, R.S.; Remy, K.E. COVID-19 disease and immune dysregulation. Best Pract. Res. Clin. Haematol. 2022, 35, 101401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weatherhead, J.E.; Clark, E.; Vogel, T.P.; Atmar, R.L.; Kulkarni, P.A. Inflammatory syndromes associated with SARS-CoV-2 infection: Dysregulation of the immune response across the age spectrum. J. Clin. Investig. 2020, 130, 6194–6197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manjili, R.H.; Zarei, M.; Habibi, M.; Manjili, M.H. COVID-19 as an Acute Inflammatory Disease. J. Immunol. 2020, 205, 12–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mavraganis, G.; Dimopoulou, M.-A.; Delialis, D.; Bampatsias, D.; Patras, R.; Sianis, A.; Maneta, E.; Stamatelopoulos, K.; Georgiopoulos, G. Clinical implications of vascular dysfunction in acute and convalescent COVID-19: A systematic review. Eur. J. Clin. Investig. 2022, 52, e13859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sullivan, B.N.; Fischer, T. Age-Associated Neurological Complications of COVID-19: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Front. Aging Neurosci. 2021, 13, 653694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tyson, B.; Shahein, A.; Erdodi, L.; Tyson, L.; Tyson, R.; Ghomi, R.; Agarwal, P. Delirium as a Presenting Symptom of COVID-19. Cogn. Behav. Neurol. 2022, 35, 123–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martins, S.; Fernandes, L. Delirium in elderly people: A review. Front. Neurol. 2012, 3, 101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cunningham, C. Systemic inflammation and delirium: Important co-factors in the progression of dementia. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 2011, 39, 945–953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simone, M.J.; Tan, Z.S. The role of inflammation in the pathogenesis of delirium and dementia in older adults: A review. CNS Neurosci. Ther. 2011, 17, 506–513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaushik, R.; McAvay, G.J.; Murphy, T.E.; Acampora, D.; Araujo, K.; Charpentier, P.; Ferrante, L.E. In-Hospital Delirium and Disability and Cognitive Impairment After COVID-19 Hospitalization. JAMA Network Open 2024, 7, e2419640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McCusker, J.; Cole, M.; Abrahamowicz, M.; Primeau, F.; Belzile, E. Delirium Predicts 12-Month Mortality. Arch. Intern. Med. 2002, 162, 457–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schnorr, T.; Fleiner, T.; Schroeder, H.; Reupke, I.; Woringen, F.; Trumpf, R.; Haussermann, P. Post-discharge Mortality in Patients with Delirium and Dementia: A 3-Year Follow Up Study. Front. Psychiatry 2022, 13, 835696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zazzara, M.B.; Ornago, A.M.; Cocchi, C.; Serafini, E.; Bellelli, G.; Onder, G. A pandemic of delirium: An updated systematic review and meta-analysis of occurrence of delirium in older adults with COVID-19. Eur. Geriatr. Med. 2024, 15, 397–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aung Thein, M.Z.; Pereira, J.V.; Nitchingham, A.; Caplan, G.A. A call to action for delirium research: Meta-analysis and regression of delirium associated mortality. BMC Geriatr. 2020, 20, 325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Titlestad, I.; Haugarvoll, K.; Solvang, S.E.H.; Norekvål, T.M.; Skogseth, R.E.; Andreassen, O.A.; Giil, L.M. Delirium is frequently underdiagnosed among older hospitalised patients despite available information in hospital medical records. Age Ageing 2024, 53, afae006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ragheb, J.; Norcott, A.; Benn, L.; Shah, N.; McKinney, A.; Min, L.; Vlisides, P.E. Barriers to delirium screening and management during hospital admission: A qualitative analysis of inpatient nursing perspectives. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2023, 23, 712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrew, M.K.; Ye, L.; Hatchette, T.; Haguinet, F.; Santos, G.D.; McElhaney, J.E.; Ambrose, A.; Boivin, G.; Bowie, W.; Chit, A.; et al. The Importance of Frailty in the Assessment of Influenza Vaccine Effectiveness Against Influenza-Related Hospitalization in Elderly People. J. Infect. Dis. 2017, 216, 405–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonanad, C.; García-Blas, S.; Tarazona-Santabalbina, F.; Sanchis, J.; Bertomeu-González, V.; Fácila, L.; Cordero, A. The Effect of Age on Mortality in Patients with COVID-19: A Meta-Analysis with 611,583 Subjects. J. Am. Med. Dir. Assoc. 2020, 21, 915–918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tejada-Vera, B.; Kramarow, E.A. COVID-19 Mortality in Adults Aged 65 and Over: United States, 2020. NCHS Data Brief. 2022, 1–8. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/products/index.htm (accessed on 12 October 2025).

- Kiely, D.K.; Marcantonio, E.R.; Inouye, S.K.; Shaffer, M.L.; Bergmann, M.A.; Yang, F.M.; Jones, R.N. Persistent delirium predicts greater mortality. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 2009, 57, 55–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ely, E.W.; Shintani, A.; Truman, B.; Speroff, T.; Gordon, S.M.; Harrell Jr, F.E.; Dittus, R.S. Delirium as a predictor of mortality in mechanically ventilated patients in the intensive care unit. JAMA 2004, 291, 1753–1762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dani, M.; Owen, L.H.; Jackson, T.A.; Rockwood, K.; Sampson, E.L.; Davis, D. Delirium, Frailty, and Mortality: Interactions in a Prospective Study of Hospitalized Older People. J. Gerontol. Ser. A 2018, 73, 415–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al Huraizi, A.R.; Al-Maqbali, J.S.; Al Farsi, R.S.; Al Zeedy, K.; Al-Saadi, T.; Al-Hamadani, N.; Al Alawi, A.M. Delirium and Its Association with Short- and Long-Term Health Outcomes in Medically Admitted Patients: A Prospective Study. J. Clin. Med. 2023, 12, 5346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dziegielewski, C.; Skead, C.; Canturk, T.; Webber, C.; Fernando, S.M.; Thompson, L.H.; Kyeremanteng, K. Delirium and Associated Length of Stay and Costs in Critically Ill Patients. Crit. Care Res. Pract. 2021, 2021, 6612187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yuan, Y.; Jiao, B.; Qu, L.; Yang, D.; Liu, R. The development of COVID-19 treatment. Front. Immunol. 2023, 14, 1125246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collins, N.; Blanchard, M.R.; Tookman, A.; Sampson, E.L. Detection of delirium in the acute hospital. Age Ageing 2010, 39, 131–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geriatric Medicine Research Collaborative. Delirium is prevalent in older hospital inpatients and associated with adverse outcomes: Results of a prospective multi-centre study on World Delirium Awareness Day. BMC Med. 2019, 17, 229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).