Deviant Behavior in Young People After COVID-19: The Role of Sensation Seeking and Empathy in Determining Deviant Behavior

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Adolescent and Young Adult Deviance as a Complex Developmental Phenomenon

1.2. Psychosocial and Trait-Based Predictors in the Pandemic Context

1.3. Study Objectives

- Bivariate associations: Sensation seeking, empathy, and COVID-19 stress (with its relationships, social isolation, and fear of contagion components) were each expected to show significant bivariate associations with deviant behavior. Specifically, sensation seeking and social isolation were hypothesized to correlate positively with deviance, whereas empathy and fear of contagion were expected to correlate negatively.

- Unique contribution of pandemic stress: When examined simultaneously with trait-level variables, COVID-19-related stress was hypothesized to account for additional variance in deviant behavior, underscoring the contextual impact of situational stressors beyond dispositional tendencies.

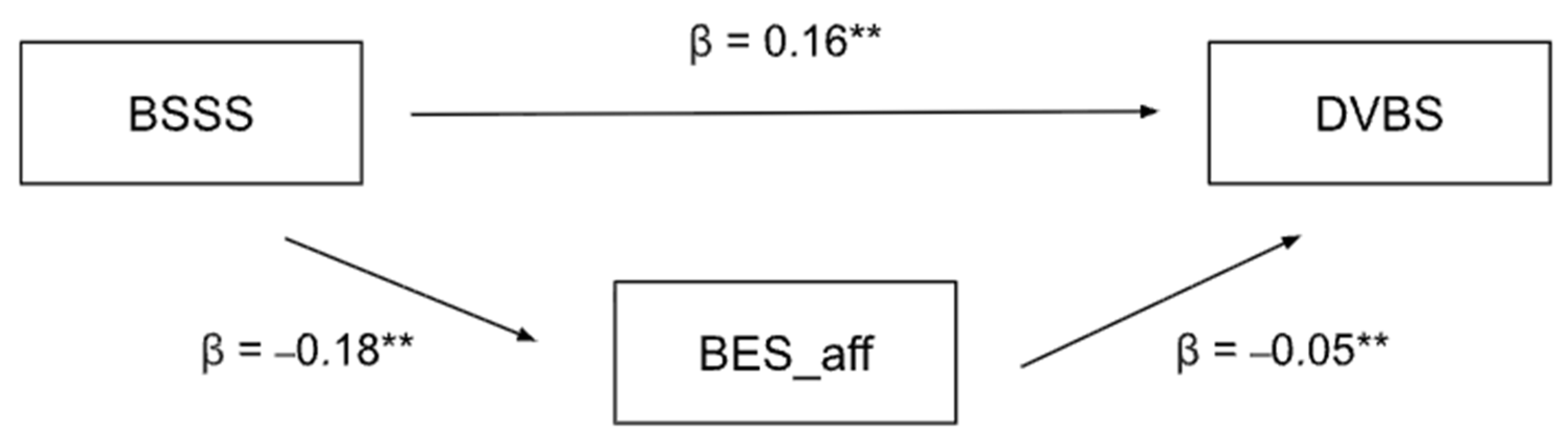

- Mediating role of empathy: Empathy was expected to partially mediate the relationship between sensation seeking and deviant behavior, consistent with its function as a socio-emotional protective mechanism.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

2.2. Procedures

2.3. Measures

2.4. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Sample Characteristics

3.2. Correlation Analysis

3.3. Regression Analysis

3.4. Mediation Model

3.5. Partial Correlation Analysis

4. Discussion

Limitations and Future Directions

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| BES | Basic Empathy Scale |

| BSSS | Brief Sensation Seeking Scale |

| CSSQ | COVID-19 Student Stress Questionnaire |

| DVBS | Deviant Behavior Variety Scale |

| IQR | Interquartile range |

| BES_cog | Subscale cognitive empathy |

| BES_aff | Subscale affective empathy |

| BES_tot | Total score of Basic Empathy Scale |

| CSSQ_rel | Subscale relationships and school life difficulties |

| CSSQ_fr | Subscale fear of contagion |

| CSSQ_is | Subscale isolation |

| CSSQ_tot | Total score COVID-19 Student Stress Questionnaire |

| SE | Standard error |

| CI | Confidence interval |

References

- Steinberg, L. A social neuroscience perspective on adolescent risk-taking. Dev. Rev. 2008, 28, 78–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moffitt, T.E. Adolescence-limited and life-course-persistent antisocial behavior: A developmental taxonomy. Psychol. Rev. 1993, 100, 674–701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farrington, D.P. Childhood origins of antisocial behavior. Clin. Psychol. Psychother. 2005, 12, 177–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loeber, R.; Farrington, D.P. Young children who commit crime: Epidemiology, developmental origins, risk factors, early interventions, and policy implications. Dev. Psychopathol. 2000, 12, 737–762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moffitt, T.E. Male antisocial behaviour in adolescence and beyond. Nat. Hum. Behav. 2018, 2, 177–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steinberg, L. A dual systems model of adolescent risk-taking. Dev. Psychobiol. 2010, 52, 216–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, J. Mental health effects of school closures during COVID-19. Lancet Child Adolesc. Health 2020, 4, 421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Loades, M.E.; Chatburn, E.; Higson-Sweeney, N.; Reynolds, S.; Shafran, R.; Brigden, A.; Linney, C.; McManus, M.N.; Borwick, C.; Crawley, E. Rapid systematic review: The impact of social isolation and loneliness on the mental health of children and adolescents in the context of COVID-19. J. Am. Acad. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 2020, 59, 1218–1239.e3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Racine, N.; McArthur, B.A.; Cooke, J.E.; Eirich, R.; Zhu, J.; Madigan, S. Global prevalence of depressive and anxiety symptoms in children and adolescents during COVID-19: A meta-analysis. JAMA Pediatr. 2021, 175, 1142–1150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Magson, N.R.; Freeman, J.Y.A.; Rapee, R.M.; Richardson, C.E.; Oar, E.L.; Fardouly, J. Risk and protective factors for prospective changes in adolescent mental health during the COVID-19 pandemic. J. Youth Adolesc. 2021, 50, 44–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shanahan, L.; Steinhoff, A.; Bechtiger, L.; Murray, A.L.; Nivette, A.; Hepp, U.; Ribeaud, D.; Eisner, M. Emotional distress in young adults during the COVID-19 pandemic: Evidence of risk and resilience from a longitudinal cohort study. Psychol. Med. 2022, 52, 824–833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Floridi, M.; Ferretti, F.; Canale, N.; Marino, C.; Uvelli, A.; Lazzeri, G. The effects of social isolation and problematic social media use on well-being in a sample of young Italian gamblers. J. Prev. Med. Hyg. 2025, 66, E153–E163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellis, W.E.; Dumas, T.M.; Forbes, L.M. Physically isolated but socially connected: Psychological adjustment and stress among adolescents during the initial COVID-19 crisis. Can. J. Behav. Sci. 2020, 52, 177–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Revital, S.S.; Haviv, N. Juvenile delinquency and COVID-19: The effect of social distancing restrictions on juvenile crime rates in Israel. J. Exp. Criminol. 2022, 6, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haver, A.; Krampe, H.; Danbolt, L.J.; Stålsett, G.; Schnell, T. Emotion regulation moderates the association between COVID-19 stress and mental distress: Findings on buffering, exacerbation, and gender differences in a cross-sectional study from Norway. Front. Psychol. 2023, 14, 1121986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Uvelli, A.; Floridi, M.; Guarino, A.; Tonini, B.; Prati, G.; Casale, S.; Masti, A.; Gualtieri, G.; Ferretti, F. COVID-19 stress, aggressiveness, and deviant behavior: A mediation analysis of youth in the pandemic era. Aust. J. Psychology 2025, in press. [Google Scholar]

- Zuckerman, M. The psychophysiology of sensation seeking. J. Personal. 1990, 58, 313–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arnett, J. Reckless behavior in adolescence: A developmental perspective. Dev. Rev. 1992, 12, 339–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harden, K.P.; Tucker-Drob, E.M. Individual differences in the development of sensation seeking and impulsivity during adolescence: Further evidence for a dual systems model. Dev. Psychol. 2011, 47, 739–746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ljubin-Golub, T.; Vrselja, I.; Pandzic, M. The contribution of sensation seeking and the big five personality factors to different types of delinquency. Crim. Justice Behav. 2017, 44, 1518–1536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mann, F.D.; Kretsch, N.; Tackett, J.L.; Harden, K.P.; Tucker-Drob, E.M. Person × Environment Interactions on Adolescent Delinquency: Sensation Seeking, Peer Deviance and Parental Monitoring. Personal. Individ. Differ. 2015, 1, 129–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jochimek, M.; Lipowski, M.; Lipowska, M.; Lada-Masko, A.B. Two sides of the same coin: Sensation seeking fosters both resiliency and tobacco and alcohol use among 16-year-olds. Int. J. Public Health 2023, 68, 1604777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eisenberg, N.; Miller, P.A. The relation of empathy to prosocial and related behaviors. Psychol. Bull. 1987, 101, 91–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, P.A.; Eisenberg, N. The relation of empathy to aggressive and externalizing/antisocial behavior. Psychol. Bull. 1988, 103, 324–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jolliffe, D.; Farrington, D.P. Empathy and offending: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Aggress. Violent Behav. 2004, 9, 441–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lovett, B.J.; Sheffield, R.A. Affective empathy deficits in aggressive children and adolescents: A critical review. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 2007, 27, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwenck, C.; Ciaramidaro, A.; Selivanova, M.; Tournay, J.; Freitag, C.M.; Siniatchkin, M. Neural correlates of affective empathy and reinforcement learning in boys with conduct problems: fMRI evidence from a gambling task. Behav. Brain Res. 2017, 320, 75–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van de Groep, S.; Zanolie, K.; Green, K.H.; Crone, E.A. A daily diary study on adolescents’ mood, empathy, and prosocial behavior during the COVID-19 pandemic. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0240349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van der Graaff, J.; Branje, S.; De Wied, M.; Meeus, W. The Moderating Role of Empathy in the Association Between Parental Support and Adolescent Aggressive and Delinquent Behavior. Aggress. Behav. 2012, 38, 368–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schoeps, K.; Monaco, E.; Cotoli, A.; Montoya-Castilla, I. The impact of peer attachment on prosocial behavior, emotional difficulties and conduct problems in adolescence: The mediating role of empathy. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0227627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jolliffe, D.; Farrington, D.P. Development and validation of the Basic Empathy Scale. J. Adolesc. 2006, 29, 589–611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Albiero, P.; Matricardi, G.; Speltri, D.; Toso, D. The assessment of empathy in adolescence: A contribution to the Italian validation of the “Basic Empathy Scale”. J. Adolesc. 2009, 32, 393–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoyle, R.H.; Stephenson, M.T.; Palmgreen, P.; Lorch, E.P.; Donohew, R.L. Reliability and validity of a brief measure of sensation seeking. Personal. Individ. Differ. 2002, 32, 401–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Primi, C.; Narducci, R.; Benedetti, D.; Donati, M.; Chiesi, F. Validity and reliability of the Italian version of the Brief Sensation Seeking Scale (BSSS) and its invariance across age and gender. TMP 2011, 18, 231–241. [Google Scholar]

- Zurlo, M.C.; Cattaneo Della Volta, M.F.; Vallone, F. COVID-19 Student Stress Questionnaire: Development and Validation of a Questionnaire to Evaluate Students’ Stressors Related to the Coronavirus Pandemic Lockdown. Front. Psychol. 2020, 11, 576758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sanches, C.; Gouveia-Pereira, M.; Marôco, J.; Gomes, H.; Roncon, F. Deviant behavior variety scale: Development and validation with a sample of Portuguese adolescents. Psicol. Reflexão E Crítica 2016, 29, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rhemtulla, M.; Brosseau-Liard, P.É.; Savalei, V. When can categorical variables be treated as continuous? A comparison of robust continuous and categorical SEM estimation methods under suboptimal conditions. Psychol. Methods 2012, 17, 354–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.H. The performance of ML, DWLS, and ULS estimation with robust corrections in structural equation models with ordinal variables. Psychol. Methods 2016, 21, 369–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liddell, T.M.; Kruschke, J.K. Analyzing ordinal data with metric models: What could possibly go wrong? J. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 2018, 79, 328–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Preacher, K.J.; Hayes, A.F. Asymptotic and resampling strategies for assessing and comparing indirect effects in multiple mediator models. Behav. Res. Methods 2008, 40, 879–891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayes, A.F. Introduction to Mediation, Moderation, and Conditional Process Analysis: A Regression-Based Approach, 2nd ed.; Guilford Publications: New York, NY, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- MacKinnon, D.P.; Lockwood, C.M.; Williams, J. Confidence limits for the indirect effect: Distribution of the product and resampling methods. Multivar. Behav. Res. 2004, 39, 99–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shrout, P.E.; Bolger, N. Mediation in experimental and nonexperimental studies: New procedures and recommendations. Psychol. Methods 2002, 7, 422–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blair, R.J.R. Responding to the emotions of others: Dissociating forms of empathy through the study of typical and psychiatric populations. Conscious. Cogn. Int. J. 2005, 14, 698–718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herpers, P.C.; Scheepers, F.E.; Bons, D.M.; Buitelaar, J.K.; Rommelse, N.N. The cognitive and neural correlates of psychopathy and especially callous–unemotional traits in youths: A systematic review of the evidence. Dev. Psychopathol. 2014, 26, 245–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Zonneveld, L.; Platje, E.; de Sonneville, L.; van Goozen, S.; Swaab, H. Affective empathy, cognitive empathy and social attention in children at high risk of criminal behaviour. J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry 2017, 58, 913–921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Chu, X.; Fan, C.; Andrasik, F.; Shi, H.; Hu, X. Sensation seeking and cyberbullying among Chinese adolescents: Examining the mediating roles of boredom experience and antisocial media exposure. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2022, 130, 107185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, Y.; Bian, Y.; Han, P.; Wang, P.; Wang, J. Associations between sensation seeking, deviant peer affiliation, and Internet gaming addiction among Chinese adolescents. Front. Psychol. 2018, 9, 2727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez, J. Sensation seeking and antisocial behaviour in a student population. Personal. Individ. Differ. 1985, 6, 725–727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qamar, F.; Quratulain, A. Impulsivity, sensation seeking, emotional neglect, and delinquent behavior among young Pakistani e-cigarette users. J. Psychol. Allied Prof. 2023, 4, 400–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| BSSS | CSSQ_rel | CSSQ_is | CSSQ_fr | CSSQ_tot | DBVS | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BES_cog | 0.05 | 0.08 | 0.11 ** | 0.07 | 0.11 ** | –0.06 |

| BES_aff | –0.15 ** | 0.19 ** | 0.14 ** | 0.25 ** | 0.22 ** | –0.15** |

| BES_tot | –0.09 | 0.17 ** | 0.14 ** | 0.21 ** | 0.21 ** | –0.14 ** |

| BSSS | 1 | 0.01 | 0.12 ** | –0.10 | 0.04 | 0.41 ** |

| B | SE | β | t | p | 95% CI Lower | 95% CI Upper | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Constant | 1.266 | 0.71 | 1.77 | 0.07 | –0.13 | 2.67 | |

| BSSS | 0.14 | 0.01 | 0.31 | 8.54 | <0.001 | 0.10 | 0.17 |

| BES_aff | –0.47 | 0.01 | –0.12 | –3.39 | <0.001 | –0.07 | –0.02 |

| CSSQ_is | 0.20 | 0.05 | 0.15 | 3.90 | <0.001 | 0.10 | 0.30 |

| CSSQ_fr | –0.38 | 0.09 | –0.15 | –3.90 | <0.001 | –0.57 | –0.19 |

| Path | B | SE | t/z | p | 95% CI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BSSS → BES_aff | –0.18 | 0.05 | –3.9 | <0.001 | [–0.27, –0.09] |

| BES_aff → DVBS | –0.05 | 0.01 | –3.77 | <0.001 | [–0.08, –0.02] |

| BSSS → DVBS (direct effect) | 0.16 | 0.02 | 9.54 | <0.001 | [0.12, 0.19] |

| BSSS → BES_aff → DVBS (indirect effect) | 0.009 | 0.004 | 2.25 | 0.025 | [0.003, 0.018] |

| ρ | p | |

|---|---|---|

| BES_aff - DVBS | –0.12 ** | <0.001 |

| BSSS - DVBS | 0.37 ** | <0.001 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Floridi, M.; Uvelli, A.; Tonini, B.; Ghinassi, S.; Casale, S.; Prati, G.; Gualtieri, G.; Masti, A.; Ferretti, F. Deviant Behavior in Young People After COVID-19: The Role of Sensation Seeking and Empathy in Determining Deviant Behavior. COVID 2025, 5, 173. https://doi.org/10.3390/covid5100173

Floridi M, Uvelli A, Tonini B, Ghinassi S, Casale S, Prati G, Gualtieri G, Masti A, Ferretti F. Deviant Behavior in Young People After COVID-19: The Role of Sensation Seeking and Empathy in Determining Deviant Behavior. COVID. 2025; 5(10):173. https://doi.org/10.3390/covid5100173

Chicago/Turabian StyleFloridi, Marta, Allison Uvelli, Benedetta Tonini, Simon Ghinassi, Silvia Casale, Gabriele Prati, Giacomo Gualtieri, Alessandra Masti, and Fabio Ferretti. 2025. "Deviant Behavior in Young People After COVID-19: The Role of Sensation Seeking and Empathy in Determining Deviant Behavior" COVID 5, no. 10: 173. https://doi.org/10.3390/covid5100173

APA StyleFloridi, M., Uvelli, A., Tonini, B., Ghinassi, S., Casale, S., Prati, G., Gualtieri, G., Masti, A., & Ferretti, F. (2025). Deviant Behavior in Young People After COVID-19: The Role of Sensation Seeking and Empathy in Determining Deviant Behavior. COVID, 5(10), 173. https://doi.org/10.3390/covid5100173