2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Design, Participants, and Data Collection

The present study used an online survey (administered via Qualtrics) to assess the psychometric properties of the MBHS and to investigate respondents’ mind-body health beliefs and behaviors. Convenience sampling methodology was applied as a means to collect responses from undergraduate students attending United States four-year residential colleges/universities. The goal of the larger survey was to gain an understanding of the undergraduate experience amid the initial shutdowns of COVID-19. A Qualtrics link was emailed to faculty volunteering to share the survey via their institution’s student communication listservs, or their course learning management sites. Snowball and convenience sampling methods were used to allow respondents to pass along the study to their peers through either direct emails, social media, or university website/listserv forwarding. Given the sampling methodology, it was not feasible to track or calculate the response rates by a student’s university given the anonymous setup of the survey.

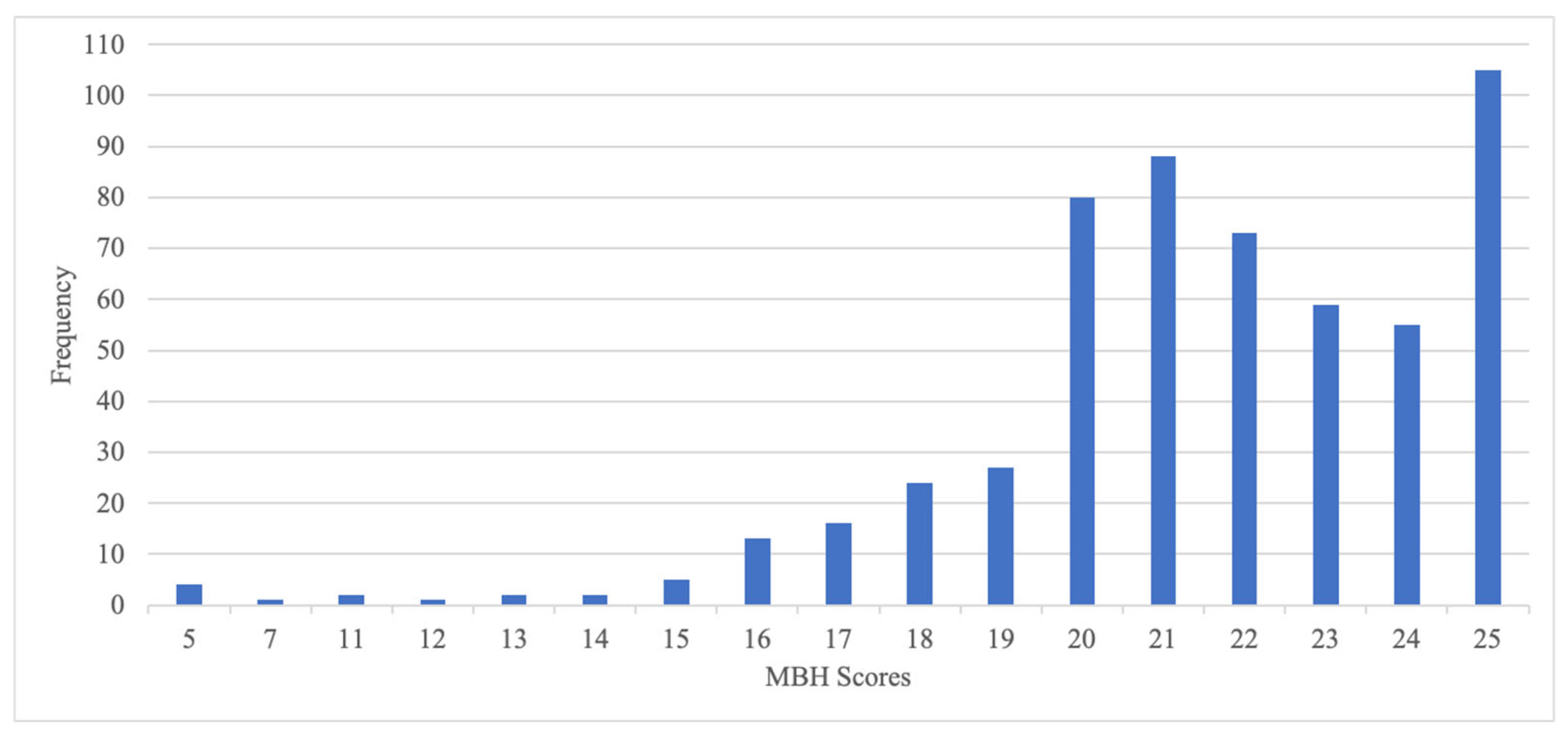

All data were collected between May 2020 and August 2020. Respondents provided an email address (which was not linked to their responses) in a random drawing for one of 100 USD 20.00 gift cards. In total, 727 individuals opened the survey, 726 consented to participate, and 557 students completed the MBHS. Listwise deletion was used in SPSS Versions 26 and 28 to select respondents who completed both the screener and mind-body health use questions.

Approval from the University of Connecticut’s Institutional Review Board was obtained under exempt status, protocol #X20-0088. Participants provided consent virtually prior to initiating the anonymous online survey, where they could leave questions unanswered if they chose and were welcome to exit the survey at any point. Participants had the opportunity to enter an optional raffle via providing an email address, which was not connected to their responses. Not all participants participated in the raffle.

2.2. Measure

The Mind-Body Health Screener (MBHS) items were developed by the second, third, and fifth authors, who are content experts, and edited by the first author. The five items included the following: (1) It is important to have a healthy mind in order to have a healthy body, (2) It is important to have a healthy body in order to have a healthy mind, (3) It is important to have a healthy mind and healthy body in order to do well academically, (4) It is important to have a healthy mind and healthy body in order to do well socially, and (5) It takes practice and effort to maintain a healthy mind and healthy body.

To assess use of mind-body health strategies both before and during the pandemic, six questions were included: Before campus was closed due to COVID-19, (1) How likely were you to engage in physical exercise, (2) How likely were you to engage in healthy eating habits, and (3) How often were you socializing (in person, going to events/activities) with your peers? Furthermore, since campus has been closed due to COVID-19, (1) How often are you engaging in physical exercise, (2) How often are you engaging in healthy eating habits, and (3) How often are you socializing (e.g., online, phone, video chat) with your peers?

2.3. Data Analysis Procedures

Analytical techniques aligned with the two-pronged purpose of the study: to examine the relation between undergraduate students’ beliefs about mind-body health during the COVID-19 pandemic and their health behaviors, while also assessing the psychometric properties of the MBHS. The psychometric analysis of the MBHS is presented first to provide evidence for the subsequent use and interpretation of scores derived from the measure. Analyses were completed in SPSS Statistics Versions 26 and 28 as well as R software and R Studio version 4.4.

To evaluate the psychometric properties of the MBHS, the team randomly split the data in half and used half in an exploratory factor analysis (EFA) and half in a confirmatory factor analysis to explore, and subsequently confirm, the underlying factor structure. Missing response patterns were first examined, and no evidence of systematic patterns that may explain missingness were found. Next steps proceeded to use a list-wise deletion for any missing responses, resulting in 280 responses for the EFA. Given the screener only had five items, it proceeded forward with a principal axis factoring (PAF) for a single factor with no rotation. The data were evaluated against the Kaiser–Meyer–Olkin (KMO) test and Bartlett’s test of sphericity. The KMO test compared the magnitude of the observed correlation coefficients to magnitudes of partial correlation coefficients for each item, while controlling for all of the other items in the correlation matrix [

46,

47]. Bartlett’s test of sphericity provided information about whether there was a relation among the items in the instrument [

48]. Next checked were the communalities, which provided information about the percentage of variance explained across the extracted factors [

49]. Finally, Cronbach’s alpha was computed for these responses to evaluate the internal consistency or the reliability of the scores.

To examine the relation between MBH beliefs and behaviors, a series of linear regressions were conducted between students’ responses for the total MBHS score and questions assessing students’ use of MBH strategies both before and during the COVID-19 campus closures.

4. Discussion

The results of the present study, specifically the disconnect between mind-body health beliefs and mind-body health behaviors, highlight similar patterns observed by medical providers in research, that health beliefs do not always align with health behaviors, especially during a pandemic [

20]. These data contradict what one would expect to find given the theorizing of the Health Belief Model [

21,

22,

23], with findings instead aligning better with the Cognitive Dissonance Theory perspective, suggesting a split between beliefs and behaviors for which one must cognitively cope [

33]. Specifically, our findings demonstrated that beliefs about one’s health did not predict (as demonstrated by a regression) one’s health behaviors; perhaps this disconnect with the HBM is unique in highly stressful and novel situations, such as the COVID-19 pandemic. Research supports the notion that stress can impact one’s cognitive functioning generally (e.g., cognitive flexibility, behavioral inhibition, working memory) [

52], as well as during the COVID-19 pandemic specifically, with these findings highlighted in a systematic review [

53]. For instance, one U.K. based study examining cognitive functioning prior to and during COVID highlighted decreased executive functioning skills and working memory abilities [

54]. These findings highlight that the experience of the pandemic (regardless of experiencing infection directly) impacted cognitive functioning. These findings may explain why behavioral changes during the school closures did not lead beliefs to impacts on behaviors, suggesting that stress likely inhibited cognitive adjustments. These data suggest that although undergraduate students may inherently have believed in the connection and importance between the mind and body as well as be conceptually interested in health behaviors, these beliefs did not immediately translate over into action regarding health-focused behaviors, a pattern reflecting the impact of cognitive dissonance in stressful circumstances.

These findings were surprising, given the original hypotheses, as the authors suspected that a widespread health crisis (such as the pandemic) would impact students’ perceptions of the health threat and thereby, their actions/values aligning around health behaviors [

24]. At the same time, critics of the model have long proposed that it may underestimate the emotional/social factors (while emphasizing the cognitive ones), overlooking cultural and social considerations [

24]. Results from the present study also highlighted that students engaged in less mind-body health behaviors prior to the campus closures, as compared to during the campus closures (with small to large effect sizes), demonstrating a change in health behaviors during the initial outset of the pandemic.

What makes these findings most interesting, perhaps, is this perspective about behaviors and beliefs within a period of immense stress, such as that of the COVID-19 campus closures. Especially for the population of the present study, college-aged students, this initial campus closure period was one of immense change and uncertainty [

55,

56]. Prior research suggests that when undergoing periods of psychological stress, individuals are actually more likely to engage in unhealthy behaviors [

38,

39], with the preference towards immediate gratification [

40]. The present findings align with emerging reports in the literature that stress may be a predictor of maladaptive health behaviors [

42], specifically related to the statistically and practically significant differences in mind-body health behaviors prior to and during the campus closures as students engaged in less health-driven behaviors.

Additionally, from a measurement development perspective, these findings suggest preliminary evidence for use of the MBHS among college students. More specifically, CFA results indicated additional areas for refinement are likely needed, perhaps to add questions to support the use of the MBHS as a standalone measure of mind-body health beliefs. Nonetheless, the preliminary evidence supports the use of this screener to ascertain college-aged students’ mind-body health beliefs, when considering programmatic planning and potential interventions. Additional practical implications of this work are discussed below.

4.1. Practical Considerations

The findings of the present study further contribute to the intersection between the Health Belief Model and Cognitive Dissonance Theory, as well as considerations of what people do when they are under stress. Practically speaking, these findings suggest that assessing for mind-body health beliefs may not be a great predictor of someone’s behavior, or at least, not be a great predictor when someone is under stress. For mental health practitioners and medical providers alike, these findings reinforce the importance of holistically understanding stressors in a person’s life when speaking about health behavior change. Furthermore, when intervening to offer support to reduce cognitive dissonance, such as through motivational interviewing (MI), a brief, evidenced-based psychological intervention aimed at enhancing ambivalence can help to facilitate change. Use of MI has extended to health care settings, with ample research supporting its use to “optimize medical interventions” [

57], p. 109 within medical offices and community clinics. Beyond the direct use of MI, the present findings highlight that it might be prudent for providers to assess patient stress on personal, societal, and systemic levels to guide conversations to actively discuss how stressors may lead to barriers or further ambivalence, aligning with the MI strategy use and general process of MI counseling.

From a measurement development perspective, this research supports universities’ use of the five items in the screener (supplemented by additional mental health assessment tools) to understand what comprehensive health services may be beneficial to undergraduate students. Such a measure in MBH-related services could provide information on which student affairs services to expand, or cut, based on students’ beliefs about mind-body health. A low total score on the screener may suggest the need for empirically supported mind-body health prevention and intervention services. On the other hand, if the total score is high, the results provide helpful insight to guide treatment interventions that may be meaningful given the student’s perspective on mind-body health and their receptiveness to the mental health and wellness programming.

4.2. Limitations

The present study was completed in the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic. Given this time period, the data collected were undoubtedly influenced by the immediate crisis occurring at that moment in time. Thus, it is important to consider that how people respond during a period of crisis may be different than their “baseline” or if these differences between their behaviors and attitudes may shift in a post-pandemic period. Regardless, the findings continue to be relevant, especially in the present study, when posed as research questions within the context of COVID-19 specifically.

An additional limitation includes potential bias in response rate, a common concern with survey design research. Furthermore, students were asked to retrospectively rate personal levels of engagement in physical exercise, eating, and socialization habits that they perhaps did not recall correctly, thereby under- or overestimating their pre-pandemic behaviors—susceptible to biases such as memory errors and social desirability—an important factor to consider. That said, the survey was administered very early in the pandemic (spring to summer of 2020), so it was in recent memory for many respondents. Next, while these data included robust quantitative measures, the team did not offer respondents a chance to fill in blank responses regarding why they believed in, or engaged with, health behaviors. In other words, the data are missing potentially rich qualitative information to supplement the statistics, a potential consideration for future research.

A final limitation of the present study concerned the sample, namely that the sample was of undergraduate U.S. college students. Thus, the findings are likely most translatable to the young adult/adolescent age group within the United States and thereby should be used with caution if generalizing to other age groups. Additionally, given the use of convenience and snowball sampling methodology, which possesses its own limitations, the approach did not include mention of the schools represented in the sample, which could have offered additional demographic context.

Specific to improvements to the MBHS, the anchors ranged from Never to Always. It may have been more useful to offer a well-defined scale that centered on the frequency of engagement in behaviors, such as 1–2 times a week, 3–4 times a week, or 5+ times a week, to concretely offer quantities instead of vague anchors. Furthermore, regarding the MBHS, future scholars should consider adding additional questions to increase the psychometric robustness of the measure, thereby increasing the evidence of reliability and validity.

4.3. Future Directions

Given these findings, future researchers may be interested in replicating this study in medical training settings to expand the understanding between mind-body health behaviors and beliefs in a wider sample of people (beyond the college undergraduate population), as well as to directly generalize to medical students. Furthermore, the survey did not ask about international student status, so future research may be interested in collecting that information to understand the cultural nuances between health beliefs and behaviors depending on individual differences between people and groups. Additionally, future research may consider examining the connection between mind-body health beliefs and behaviors from a mixed-methods approach to integrate robust quantitative data with insightful qualitative information and to understand the “why” behind certain alignments and discrepancies in mind-body health beliefs and behaviors.

5. Conclusions

What we believe about health, specifically the connection between the mind and the body, may not translate directly over to how we act, whether through exercise patterns, eating, or socialization, a finding highlighted in the present study suggesting that college students during the COVID-19 campus closures did not find their beliefs about health to translate to their behaviors across various dimensions of health: nutrition, exercise, or social well-being. The present study’s findings, aligning with Cognitive Dissonance Theory, suggested that for undergraduate students, their beliefs and behaviors did not relate both for behaviors reported pre- and post-campus closures. Interestingly, students engaged in less health-related behaviors during the closures, an immense period of stress, perhaps speaking to a moderating role of stress as related to the connection between health beliefs and health behaviors. Given that U.S. college students reported engaging in less health behaviors (with small to large effect) during the campus closures as compared to prior to the campus closures, these findings highlight the criticality of understanding stress in one’s life when seeking to understand the relation between their beliefs and behaviors—a relevant takeaway for providers to recognize when assessing readiness for health behavior change.